We Want Politicians to Fear Women's Voting Power

November 7, 2022NEWS,NEWSLETTER

November 7, 2022 ‘Twas the night before elections, and all through the House, every creature was stirring, even that guy that looks like a mouse. I could keep going, but I dropped out of my poetry elective in college for a reason. So let’s talk turkey, folks. Tomorrow is the big day. (Here at The Meteor, our offices will be closed.) So tonight, we’ve got some last-minute treats: an interview with Supermajority’s Amanda Brown Lierman on why women could literally change the outcome of tomorrow’s election—and voter guides to help you do it. Running out of rhymes, Shannon Melero  WHAT TO KNOWWho’s who: Still unsure who to choose in your state’s local election? This handy tool from Vote411 allows you to select your state and search for candidates, ballot measures, eligibility requirements, polling place locators, campaign finance information, and more. If this is your first time voting, PLEASE check eligibility requirements before going to your polling place. Some states are extremely specific about acceptable forms of ID (yes, it’s a strategy) and you don’t want to get turned away. (If you do, though, STAY in line and call the Election Protection Hotline.) Voting the issues: So you know who you’re voting for—but are you certain about what you’re voting for? Voting for the first Democrat you see on the ballot by default may have worked in the past, but with so many of our rights on the line, it’s time to read the fine print. Here are some guides curated by groups we know and trust:

FROM THE EXPERT“Our Oppressors Win When We Divide Ourselves”Amanda Brown Lierman talks to us about creating the most powerful voting bloc possible.BY SAMHITA MUKHOPADHYAY  LOOK HOW HAPPY WE COULD ALL BE IF WE VOTED! (IMAGE BY JEMAL COUNTESS VIA GETTY IMAGES) You already know you have to vote (and we trust that you will.) But how much difference will your vote make? And what is likely to happen tomorrow? For a view from the front lines, I turned to the executive director of Supermajority (an organization working to build national political power for women), Amanda Brown Lierman. Amanda has been working in the voting rights space for years: she used to work at Rock the Vote and was the organizing director at the Democratic National Committee. We’re also good friends and former colleagues. I wanted to hear from her what exactly is at stake tomorrow…and what’s giving her hope. Samhita Mukhopadhyay: How are you feeling about the midterms right now? Amanda Brown Lierman: I feel like the only thing I can do is hold hope. It is just amazing to see the commitment of women [at Supermajority] who are freaking tired and have every reason to be too tired to do this work. But they're showing up and they're showing out when it really does matter. Of course, I feel anxious because there's also so much at stake and so much on the line. Usually at this point in an election cycle, you spend a lot of time talking about why it's so important to vote for somebody. And there are incredible pro-women champions and pro-women leaders who are running for office. But there are also names on that ballot of people who don't deserve to be sitting in those seats of power. And in many cases, they are power-hungry white men who are not serving women, not serving the people who put them in office, and they need to be kicked out of those seats. Can you spell out a little bit what’s at stake? The president has made a couple promises about what he can and will do if we get him two more Democratic senators [giving Democrats a majority irrelevant of how Sens. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Joe Manchin of West Virginia vote]. And there are some really incredible women who are running for Senate. If we could deliver those two new Democratic senators, then we can actually make progress in some of those national policy conversations around childcare access, around paid leave, and other care economy issues that were cut out of Build Back Better. We could codify Roe at the national level. The gubernatorial races are going to be very important too. Gretchen Whitmer has been the number-one defender of women's rights in Michigan since she was elected in 2018. There’s also that ballot initiative in Michigan which intends to enshrine abortion as a constitutional right in the state. In Michigan—this is actually incredible, Samhita—in order to get an initiative on the ballot, you have to have something like 400,000 signatures. And they had 750,000 signatures for this ballot initiative in Michigan—double what was necessary, double what people thought was impossible to get done.  PROTESTORS IN DETROIT, MICHIGAN SHOWING UP AND SHOWING OUT FOR ABORTION RIGHTS. (IMAGE BY MATTHEW HATCHER VIA GETTY IMAGES) We saw something similar in Kansas in August, where voters voted to protect abortion rights. What are you seeing in the post-Roe political landscape? For so long, people have run away from having conversations about abortion, and abortion [historically] has been more of a polarizing issue than it has been a mobilizing issue. And what I think we're seeing in this landscape is abortion right now is not polarizing. It's actually created the opportunity for us to build coalitions in a way that we have never done before. And Kansas is such a great example of that. You have folks in Kansas, women in particular, who voted no on that amendment to make sure that we did not advance abortion bans in that state. Organizing is all about having conversations. It's all about connecting with somebody over a shared set of values. Women might not [all] have the same experience; they might not be motivated by the same issue. But I feel like we have been able to build connections, build coalitions around this value that our bodies should be respected and that women should be able to make a decision about their bodies—instead of power-hungry men who are sitting in a political seat. That's what gives me hope: the ability to think about abortion as a coalition-building issue, which is a new phenomenon for us. Oh, I love that. We want to make sure that women recognize their power as individuals, as voters, but also claim the power that we have as a collective. And our coalition, hopefully, is a voting bloc that is respected, is revered, and is... also, if I'm being honest, a little bit feared. I want politicians to be afraid of a whole lot of women voting because they have to be accountable to the very people that put them in office. Our oppressors win when the walls go up, and we divide ourselves. There are some signs that there could be record turnout. I voted in upstate New York, and it was a 45-minute wait to vote a week before Election Day. Wow. But the fact that the Zeldin/Hochul race feels so close in New York is not a great sign to me. I know you've worked in the voter space for a long time. What can we actually expect tomorrow? I think that there are people (notably Democrats) who have been dismissing this election for the last year with a sort of despair and just [resigning] to loss. So I do refuse to sort of give into that, and think it is our job to make sure that we do the work because change happens with one conversation, one voter. And that commitment to organizing, I think, is the only thing that has always worked, and has always saved us. But to your point: These elections are fucking close. And I think many of them will come down to field margins. And there's a reason why we have to give it our all, because some of these elections will be won or lost by two votes, by a hundred votes. And so this idea of giving in just makes me sick to my stomach and so angry. Because literally, if we each spent the time talking to—I mean, honestly, two to three people in the next couple of days and got them to the polls, it wouldn't be close. I think voting is an expression, and Election Day will be an expression of the collective as women flexing our political muscle and making sure that our voices are heard and demanding that of our elected leaders. I've been saying this a lot: They can ignore our primal screams, but they cannot ignore our votes.  PHOTO BY HEATHER HAZZAN Samhita Mukhopadhyay is a writer, editor, and speaker. She is the former Executive Editor of Teen Vogue and is the co-editor of Nasty Women: Feminism, Resistance and Revolution in Trump’s America and the author of Outdated: Why Dating is Ruining Your Love Life, and the forthcoming book, The Myth of Making It.  THANK A POLL WORKERToday is Election Hero Day, a day to recognize and thank all the folks who make it possible for us to show up and cast our votes. That includes your state directors, local clerks, staff, and (everyone’s favorite) the volunteers that hand out the “I Voted!” stickers. And they need support: They’re short-staffed, and too often under attack. Spread the love by sharing the image below from @electionheroday or kick it old school and thank an election worker face-to-face. (But keep a respectable distance; we are still in a pandemic.) (SCREEN SHOT VIA INSTAGRAM) Remember, Election Day is a marathon, so drink water, be patient, be kind—and above all, be there! We’ll see you on the other side.  Speaking of marathons, did you run the New York City Marathon this weekend? Let us hype you up! Send your marathon pics to [email protected] and we'll include them in a future newsletter. FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Stacey Abrams and Katie Hobbs On Running for Governor

|

Buona sera, Meteor readers, Before we get into anything, let’s address the elephant in the room. You know exactly what I’m talking about: Mariah Carey officially announced the start of the Christmas season on November 1 (which, for those lost in the space-time continuum, was two days ago). Can we please let November live!? We need to get through Thanksgiving, Mariah. Calm your reindeer. After all, we’ve still gotta get through Election Day. In today’s newsletter, we’ve got an exclusive interview with Stacey Abrams and Arizona Secretary of State Katie Hobbs, who are running for governor of Georgia and Arizona, respectively. Abrams is up against incumbent Republican Governor Brian Kemp, and Hobbs is in a heated showdown with Kari Lake, a Trump-endorsed election denier who recently said she wants a “carbon copy” of Texas’ abortion ban. The stakes are dire. But first, a little news—and some heroic doctors hanging out in DC. Not jingling any bells, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONRemembering Momen Zandkarimi: Unrest in Iran continues following the death of Mahsa Amini, who is believed to have been killed by Iranian security forces in September. The subsequent protests have led to the deaths of several other women, including Iranian TikToker Hadis Najafi, who was reportedly shot by Iranian police during a protest. And now Hengaw, a Kurdish human rights organization, reports that during a protest held in conjunction with Najafi’s mourning ceremony, another young person was killed. The victim, Momen Zandkarimi, was only 18 years old—and joins the at least 277 protesters whose deaths have been directly caused by Iran’s security forces this fall, according to Iran Human Rights (IHRNGO). Instead of seeking justice for the almost 300 lost lives, IHRNGO reports that the Iranian government has arrested dozens of protestors and charged them with “moharebeh (enmity against god) and efsad-fil-arz (corruption on earth) which [both] carry the death penalty.” IHRNGO believes the government will follow through on the death penalty in an effort to suppress further political uprising. AND:

DOCTORS FOR ABORTION ACCESS DAY OF ACTION AT THE U.S. CAPITOL. (PHOTO BY KISHA BARI)

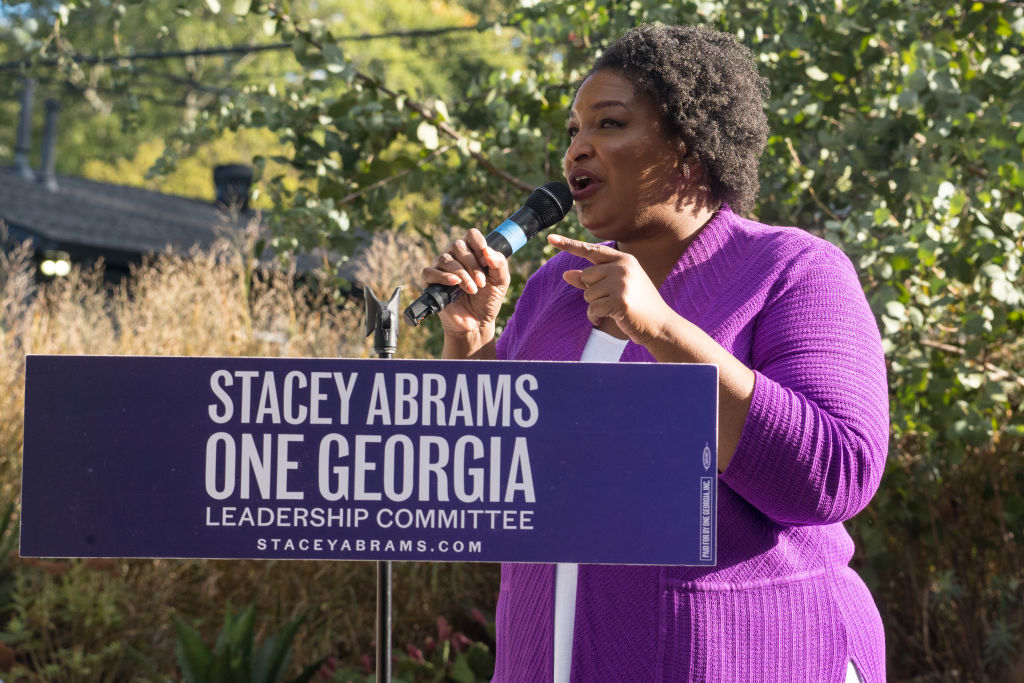

THE 11TH HOUR INTERVIEWWith Five Days to Go, Two Women Running for Governor Talk to The MeteorStacey Abrams and Katie Hobbs on their historic runs: “It’s helpful to have someone who understands what you’re going through.” BY ASHLEY SPILLANE  THE HONORABLE STACEY ABRAMS. (IMAGE BY MEGAN VARNER VIA GETTY IMAGES) The people we elect on November 8 will decide the future of voting rights, abortion rights, healthcare, the economy—and so much more. And in many states, protecting key civil rights will come down to the results of a single race: governor. With five days to go until Election Day, I talked to two candidates I’ve had the privilege to meet through my work in civic engagement: Stacey Abrams, the voting rights champion from Georgia who could become the country’s first Black woman governor, and Katie Hobbs, the Arizona Secretary of State who oversaw the 2020 election administration and now finds herself in a tight race against Kari Lake. Both women are running for the highest office in their state, and the stakes couldn’t be higher. Ashley Spillane: You’re both running for governor. Tell me more about why this position matters. Stacey Abrams: Governors are the CEOs of the entire state, charged with implementing laws, crafting a budget, and overseeing state operations. Most people think of Washington, DC when they think about who has the greatest impact on policy, but the truth is…governors have the most impact on our lives. We know it is so important to have women in all kinds of leadership roles; studies have shown [corporate] female CEOs make better political leaders, are better with money, are better collaborators, and care more about others than their male counterparts. Having women serving in the highest state office willing to collectively lead important debates is critical. Over reproductive rights, of course—but also about voting rights, marriage equality, kitchen-table economic issues, and how our democracy as a whole should operate more equitably. Katie Hobbs: Despite making up over half the U.S. population, women constitute just 24% of the Senate, 28% of the House, and about 30% of all state legislative seats. Since its formation, 116 people have served on the Supreme Court; only six of them have been women, four of whom are serving now. Not to mention that literally every U.S. president who has appointed these judges has been a man. As for governors, there are only nine women in those roles right now. Many of them are seeking re-election this year. Some [candidates], like me, are running against anti-choice women, and others, like in Stacey’s race, are challenging male incumbents who have vowed not to use their veto pen to protect our rights. If legislatures pass even more of these cruel laws, governors are the last line of defense to stop them.  ARIZONA SECRETARY OF STATE, KATIE HOBBS. (IMAGE BY MARIO TAMA VIA GETTY IMAGES) Governors’ races seem more hotly contested this year. Why now? Katie: We’re at a crossroads for our democracy, and everyone’s realized the importance of state officials in protecting (or killing) it. I’m running against someone who denies the 2020 election results and has not said if she will accept the results if she or her party lose in the future. There are people running for governor, secretary of state, and attorney general across the country who are actively undermining our democracy and working to overturn the will of the people for their own political gain. Stacey: As the Supreme Court removes federal protections and devolves them to the states, governors will also serve as a last line of defense for your hard-fought rights. In this post-Dobbs, post-January 6 era, with voting rights and civil liberties at stake, women governors are positioned to lead a nationwide effort to take back the decisions that should be ours alone. Little girls growing up in this era, particularly little girls of color, are counting on women leaders.  Ashley Spillane is a social impact strategist, civic engagement expert, and founder/CEO of the (nearly) all-female firm, Impactual. Her work has been featured on The Washington Post, The New York Times, Harvard Business Review, Glamour, and Marie Claire. FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

With Five Days to Go, Two Women Running for Governor Talk to The Meteor

A home for modern feminism

Stacey Abrams and Katie Hobbs on their historic runs

BY ASHLEY SPILLANE

November 3, 2022

The people we elect on November 8 will decide the future of voting rights, abortion rights, healthcare, the economy—and so much more. And in many states, protecting key civil rights will come down to the results of a single race: governor.

With five days to go until Election Day, I talked to two candidates I’ve had the privilege to meet through my work in civic engagement: Stacey Abrams, the voting rights champion from Georgia who could become the country’s first Black woman governor, and Katie Hobbs, the Arizona Secretary of State who oversaw the 2020 election administration and now finds herself in a tight race against Kari Lake. Both women are running for the highest office in their state, and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Ashley Spillane: You’re both running for governor. Tell me more about why this position matters.

Stacey Abrams: Governors are the CEOs of the entire state, charged with implementing laws, crafting a budget, and overseeing state operations. Most people think of Washington, DC when they think about who has the greatest impact on policy, but the truth is…governors have the most impact on our lives.

We know it is so important to have women in all kinds of leadership roles; studies have shown [corporate] female CEOs make better political leaders, are better with money, are better collaborators, and care more about others than their male counterparts. Having women serving in the highest state office willing to collectively lead important debates is critical. Over reproductive rights, of course—but also about voting rights, marriage equality, kitchen-table economic issues, and how our democracy as a whole should operate more equitably.

Katie Hobbs: Despite making up over half the U.S. population, women constitute just 24% of the Senate, 28% of the House, and about 30% of all state legislative seats. Since its formation, 116 people have served on the Supreme Court; only six of them have been women, four of whom are serving now. Not to mention that literally every U.S. president who has appointed these judges has been a man.

As for governors, there are only nine women in those roles right now. Many of them are seeking re-election this year. Some [candidates], like me, are running against anti-choice women, and others, like in Stacey’s race, are challenging male incumbents who have vowed not to use their veto pen to protect our rights.

If legislatures pass even more of these cruel laws, governors are the last line of defense to stop them.

Governors’ races seem more hotly contested this year. Why now?

Katie: We’re at a crossroads for our democracy, and everyone’s realized the importance of state officials in protecting (or killing) it. I’m running against someone who denies the 2020 election results and has not said if she will accept the results if she or her party lose in the future. There are people running for governor, secretary of state, and attorney general across the country who are actively undermining our democracy and working to overturn the will of the people for their own political gain.

Stacey: As the Supreme Court removes federal protections and devolves them to the states, governors will also serve as a last line of defense for your hard-fought rights. In this post-Dobbs, post-January 6 era, with voting rights and civil liberties at stake, women governors are positioned to lead a nationwide effort to take back the decisions that should be ours alone. Little girls growing up in this era, particularly little girls of color, are counting on women leaders.

Speaking of the post-January 6 era, how has it been to run for office during this time?

Katie: It’s certainly moved the conversation away from the serious challenges facing our state, and instead, we’re relitigating things that should be settled facts. I’m asked every day if I’ll accept the results of this upcoming election, if I’ll certify the 2024 presidential election as governor, and if I believe in the integrity of our democratic systems and institutions. Of course, my answer is unequivocally yes to all three, but my conspiracy theorist opponent disagrees. And so, these basic facts have become part of our political discourse throughout this campaign.

And then there’s the heightened level of vitriol. I’ve received numerous death threats, I’ve had armed protestors outside my home, and my children have been the subject of threats. [Just last week, Secretary Hobbs’ campaign office was broken into.]

How do you navigate campaigning in such an intense political environment?

Stacey: I stay focused on what is at stake—for women’s rights, for our democracy, for people of color. My opponent, Brian Kemp, is considered the architect of modern voter suppression by denying over a million Georgians access to the ballot. Katie’s opponent is someone who has advocated against the outcomes of elections and for overturning the will of the people. Both are clear and present dangers to our democracy.

I am supported by an incredible group of women who are in similar positions, running for statewide office this year to protect our democracy and our rights. Katie and I have gotten to know each other by sharing this experience, and it helps.

Katie: Stacey and I have developed a real friendship through this process, not just with each other but with women who have run for governor (and won) before, like Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan. We face similar challenges as female candidates: fighting to raise money, doubts about your ability, expected deference to male counterparts, questions about your appearance and looking gubernatorial—especially in this polarized political environment.

At the end of the day, it is helpful to have someone who understands what you’re going through. Stacey and I stay in touch by phone and text. She’ll send a virtual high-five if she sees me on TV or checks in on how I’m doing after more reported threats.

For people reading this feeling demoralized by politics, what do you want them to know?

Stacey: First: Don’t lose hope. Governors have disrupted the over-reaches of government before, and they have moved much faster than Congress. As an example, governors signed legislation granting the right to vote to women and legalizing abortion long before Congress or the Supreme Court got in on the action. If you care about these things, read up on who is running for governor in your state and vote accordingly.

Second: Get to the polls. Bring your friends, bring your enemies, bring people you’re mad at and people who are mad at you. Bring people you broke up with and the people you want to get with.

Finally: Stay involved. Should Katie and I win our gubernatorial races on November 8, we will most certainly govern with anti-choice, anti-voter, male-dominated Republican majorities in both chambers of our respective state legislatures. We are not [just] the last line of legislative defense for women and voters in our states (especially women and voters of color) and for our LGBTQ+ communities; we are the only defense. Having realistic expectations of what we can do—and getting familiar with who represents you at the very local level—can help us.

Katie: And be sure to talk to your friends, family, and colleagues about what’s at stake in these races. Only half the country voted in the last midterm election, after all.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Ashley Spillane is a social impact strategist, civic engagement expert, and founder/CEO of the (nearly) all-female firm, Impactual. Her work has been featured on The Washington Post, The New York Times, Harvard Business Review, Glamour, and Marie Claire.

What You Don't Already Know About Extremism

October 27, 2022NEWS,NEWSLETTER

|

Greetings, Meteor readers, Happy Thursday before Halloween! We don’t want to spook you out too much, but the midterm elections are in 13 days. That is scarier than Freddie Krueger! This week, Meteor co-founder Cindi Leive spoke with journalist Kyle Spencer about what’s really behind the rise of far-right extremist groups on college campuses. Your horror movie marathon’s got nothing on the realities of young, college-educated men being trained to “weaponize” their cell phones against their peers. But before that, my colleague Shannon has rounded up a few more races to watch this year—and, of course, the news. Have a boo-tiful weekend! (I’ll see myself out.) 🥁 Samhita Mukhopadhyay   QUICK ELECTION MOMENTHere are three races we’ve got our eyes on this week, plus an action item from our friends at Supermajority. The Texas AG race - Some good news out of the Lone Star State! Democrat Rochelle Garza is running to unseat Ken Paxton as Attorney General, and she actually has a shot at winning, despite Texas’ reputation of always going red. Refreshing your memory, Paxton is not only anti-abortion but has pushed for anti-trans legislation, supports book banning in libraries, and even tried to criminalize family-friendly drag shows. It goes without saying, but I will say it anyway: There is so, so, so much at stake in this one race. The Michigan Secretary of State race - This one might be flying under your radar. But as Teen Vogue lays out plainly, this race is all about voting rights. So who’s running against sitting Democrat Jocelyn Benson? The Republicans selected Kristina Karamo, an election denier who believes the January 6 insurrection was orchestrated by “Antifa” members dressed up as MAGA supporters. Ironically, Karamo’s main platform is election integrity and security. According to Teen Vogue, Karamo was initially “[a candidate] of the America First Coalition, an organization that seeks to restrict Americans’ voting rights by creating barriers between them and the polls.” Still need another red flag? Karamo has Donald Trump’s endorsement. The Oregon Governor’s race - This showdown in Ducks country also needs more attention. While Oregon has been reliably blue, Rebecca Leber of Vox put together a fascinating overview of how special-interest groups and Nike co-founder Phil Knight have been chipping away at Oregon’s blue veneer. And the chisel is Republican candidate Christie Drazan, who is running against Democrat Tina Kotek and the unaffiliated candidate Betsy Johnson (no relation to the fashion designer). Climate action sits at the heart of this race. “If Drazan wins, Oregon would become the first state in the West to reverse course on its climate goals,” Leber reports. And that’s not hyperbole; it’s simply what happens when one accepts millions of dollars in campaign funding from a logging group with ties to alt-right militias. So now the question is, what can you do? (Other than vote. Have we mentioned you really need to vote?) This Saturday, Supermajority is hosting two events you can be a part of. The first is a virtual text bank with Megan Rapinoe and the #WomenAreVoting Coalition to encourage women voters in Georgia and North Carolina to get out and vote for the things we believe in. (IMAGE COURTESY OF SUPERMAJORITY) For anyone in Michigan, Supermajority is also hosting a Day of Action Canvass in Dearborn Heights where volunteers will go door-to-door sharing information on voter registration. PLUS:

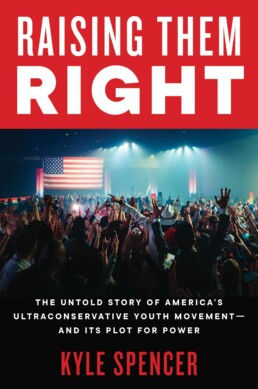

EXTREMISM WATCHThe Proud Boys Are Scary. These Organizations Are ScarierThat's the message behind a new book about the rise of the right on campusBY CINDI LEIVE  A YOUNG MAN ATTENDING AN "AMERICA FIRST" EVENT HOSTED BY TURNING POINT USA IN DECEMBER OF 2021. (IMAGE BY SPENCER PLATT VIA GETTY IMAGES) Extremism is everywhere: Election deniers are running for office. Antisemitism is on the rise. Proud Boys and Oath Keepers are regularly disrupting events, holding rallies, and threatening to interfere with elections. Not to mention the fact that friendly TV personality Dr. Oz now wants your local councilperson to have a say in your medical decisions. None of this is a surprise to journalist Kyle Spencer, who’s been embedded with the rising stars of this country’s increasingly visible and vocal right wing for the last four years—spending up-close time with right-wing activists like Charlie Kirk and Candace Owens, plus the young people who are joining their movement. All of this is documented in her new book Raising Them Right: The Untold Story of America's Ultraconservative Youth Movement and Its Plot for Power. I had questions. *** Cindi Leive: What are we getting wrong about what the right-wing really is in this country? Kyle Spencer: It kind of depends on whether or not you’ve been close to a college campus recently. I think there’s a lot of fear and concern about the Oath Keepers and the Proud Boys and these really aggressive groups that are openly radical. And they’re going after the kid in his bedroom playing video games all day…[But] I argue that, no, we should be more alarmed with these [groups] that are on college campuses recruiting people as if their ideas are really normal and mainstream. White boys are a very big target for them. And they often like to start with an issue that you care about. You know, if a kid [says], “Sometimes I feel like I can’t really say what I want,” they start there and then radicalize. But they sell it with a smile. And they try to stay really far away from political issues and stay more with culture. They’re very strategically and surgically trying to normalize ideas like gun ownership, nativism, [and] pro-American, anti-immigration sentiments, which veer very quickly into racism and, in some cases, anti-Semitism. And people don’t realize a lot of this actually is [campus] partnerships with the Christian right. To me, that’s the most alarming, [that they are pulling students into] this Christian nationalism. These really draconian ideas that, you know, God chose America. God runs America. The Constitution is a divine document. And the Bible is always above the Constitution. So much of what we hear about the cultural climate on college campuses focuses on the perceived “cancellation” of people on the right. I feel like I’ve heard more concern about that than I have about this phenomenon that you’re documenting. Is there a misperception of campus life? Yeah. It’s really a myth that there are all these free-speech issues on college campuses. Now, a lot of professors are pretty progressive. This is just a truth. But students are much more divided. I try to remind people that four in 10 young people voted for Trump in 2020. So this idea that young people are so radically progressive is just not true. What you see on these college campuses is, there are instances of intolerance among progressives. What these right-wing groups do is catch them and to edit them and throw them up on the Web to get them to go viral with the help of right-wing media outlets. One of the tools they use, obviously, is their cell phones, and they’re told in their training to “weaponize their phone.” So [the left-wing intolerance] is not nearly as prevalent as we’re told it is. And the reason is that they have created a national campaign [that] starts on the fringes—Breitbart and some of these right-wing college sites—and then bleeds into The Wall Street Journal. And eventually, The New York Times believes that this is a huge problem.  A PROTEST AGAINST RIGHT-WING SPEAKERS ON CAMPUS IN 2017. (PHOTO BY DAVID MCNEW VIA GETTY IMAGES) You said that they’re told in their training to “weaponize their phones.” Where are those trainings taking place, and led by whom? The Leadership Institute is the conservative training academy. It received $25 million last year. It was started in the seventies. Everybody that you know that’s a right-wing activist went through the academy: Tucker Carlson, Karl Rove, Pence. And so what happens is that everybody speaks the same language because they were all trained in the same place. So when you say “weaponize your phone,” everybody knows what you’re talking about. When you say “I’m willing to bleed for the cause,” everybody knows what you’re talking about. If you refer to a “3 a.m. type,” you’re starting your college group, and you’ve got to find the people you can call at 3 a.m., hard workers. Everybody knows. They have this whole vocabulary—which the left does not. They’re all talking the same language. And every [right-wing] donor—wealthy, mid-tier, low-tier—they’re going to give a little money to the next generation, and a lot of it goes through the Leadership Institute. Which, again, is not what [the left] does. You’re making a distinction between this movement and the dark underbelly of Oath Keepers, Proud Boys, and Q Anon. But do these groups intersect? What these folks do a lot is kind of wink at the [fringe] right. But the distinction is that the groups that I’m writing about [like Turning Point USA] are baked into the establishment. They’re funded by the establishment. That’s why they’re scarier. And they have a lot more money. You’ve talked about religion and anti-immigrant sentiment as being big motivations for people to join these groups. How much of this has to do with white men feeling—incorrectly—like they’re the most attacked group on the planet right now? It’s central. I’d almost like to find a more complicated answer. But I think that this fear and anxiety among white men that they’re ceding power to people of color and to women—this replacement theory—is extraordinary. And I think what we’re seeing is that anxiety playing itself out. And for women [who join these groups], they can be receptive to [these] ideas…but most of the young women I talked to [already] came from conservative families. I didn’t see as many women being “turned”—I saw boys being turned. A lot of boys came from moderate or Democrat families. You reeled off that scary figure that four in 10 young people voted for Trump in 2020. We’re just a couple weeks away from these midterms. What’s your sense of the appeal of the right to young voters right now? What I saw a lot on college campuses is not that these right-wing groups were able to [persuade Democrats to vote Republican]. What they were able to persuade them to do was not go to the polls. It’s a kind of hidden voter suppression: They’ll just kind of pound, pound, pound: “Joe Biden’s an idiot. He’s falling off his bicycle.” “These lefties on campus won’t let you say what they want. And they support affirmative action, which means slots taken away from you.” And they just keep pounding it, but they turn people off from the Democrats so they don’t go to the polls. So if we see a relatively low voter turnout, it would be a sign to me that these guys are continuing to be successful with this. But I don’t know. I mean, I’m not going to lie. I don’t know how it’s going to go. Neither do you. Nobody does.  Cindi Leive is the co-founder of The Meteor, the former editor-in-chief of Glamour and Self, and the author or producer of best-selling books including Together We Rise.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Do NOT Ignore These Midterm Races

October 25, 2022NEWS,NEWSLETTER

|

Greetings, Meteor readers, This weekend I sojourned into the forests of upstate New York to be one with the leaves and listen to Midnights on an endless loop. And while that was great, it was also a bit alarming to drive past confederate flags, enormous signs that read “Fuck Biden,” and—for the local flavor—a few disparaging posters about Governor Kathy Hochul.  This feels like the perfect time to remind all our New York readers that Hochul and her opponent Lee Zeldin are on the ballot this November 8. And Zeldin is an anti-abortion Trump supporter who is now surging in the polls. This is not the time to assume blue states will stay blue no matter what. As far as the national landscape goes: In today’s newsletter we’ve got a refresher on the midterm races we have our eye on, the candidates who say they will fight for bodily autonomy—and of course, the news. Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONNo justice for BG: WNBA star Brittney Griner, who was detained in Russia in February after officials found cannabis oil cartridges in her luggage, has lost her appeal and will officially be serving a nine-year sentence in a Russian penal colony. Griner’s 250-day detention in Russia was officially recognized as a wrongful detention by the U.S. government in May, and the Biden administration tried for a prisoner swap in July, offering up Russian arms trafficker Viktor Bout in exchange for Griner and fellow American detainee Paul Whelan. But the attempt came to naught when the Russians chose to counteroffer instead of following through on the swap. Unless the U.S. finds another way to intervene, it is very likely that Griner will remain in Russia until the end of her sentence.  BRITTNEY GRINER APPEARS IN COURT DURING HER TRIAL IN JULY. (IMAGE FOR THE WASHINGTON POST VIA GETTY IMAGES) Eyes on the prize: Election Day is two weeks from today, and state races have never been so crucial. What happens this November will lay the groundwork for months, even years to come—partly because the state legislators and attorneys general who are elected this fall will be the ones ruling on the outcome of the presidential race in 2024. And if the Republicans have their way, the “red tsunami” could reawaken the Ghost of Orange Presidents Past—and that is NOT the spooky season I signed up for. For the next two weeks, we’re going to pull out a few key races we have our eye on: Georgia - There are several heated races in the peach state. As you probably know, Reverend Raphael Warnock is locked in a tight race defending his U.S. Senate seat against Trump-backed Herschel Walker, who recently had to shift his tune on abortion rights when a woman claimed she was paid by Walker to terminate her pregnancy. But as you might not know, there are also four proposals for changes to the state’s constitution on the ballot; voters can read up on them here. One proposal could change how property owners are taxed after their properties are damaged or destroyed by a natural disaster, a hugely important change considering the extreme weather we’ve been seeing across the country. And last, but never least, Stacey Abrams is running for Governor against incumbent Brian Kemp. Abrams is a leader in voting rights and she has promised to fight for abortion rights. If elected, she will be the first Black woman governor in American history. Pennsylvania - TV doctor, Republican, and New Jersey native Mehmet Oz is up against Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman for the state’s open U.S. Senate seat. Fetterman is still leading in the polls, but Oz has been rubber-stamped by Trump and Mitch McConnell—which means anything can happen. Let’s also not forget that after Fetterman suffered a stroke and was unable to attend an in-person debate, Oz used that as fodder for smear campaigns. What happened to first do no harm? Nevada - The race between incumbent Democrat Catherine Cortez Masto and Republican challenger Adam Laxalt for U.S. Senate is according to CNBC, “one of the GOP’s best chances to flip a blue seat red.” Laxalt has been wooing voters with a “tough on crime” platform backed by local police groups, while simultaneously attacking the FBI on behalf of Donald Trump. Like too many other high-profile GOP candidates, Laxalt has also been regurgitating the far-right’s claims about voter fraud in 2020. Meanwhile, Cortez Masto has worked to draw attention to the crisis of missing Indigenous women.  AND:

Please share this newsletter with anyone who needs to be reminded that elections are coming. FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Georgia Tries to Define "Personhood"

October 20, 2022NEWS,NEWSLETTER

|

Wonderful Meteor readers, On Tuesday, we shared with you the heart-wrenching story of Amanda Zurawski and her devastating pregnancy loss made worse by anti-abortion laws in Texas. The reactions to Amanda’s story from you, our readers, have been incredible—covered in People, discussed on MSNBC, and shared by the Vice President herself. We’re so grateful her story is resonating. AMANDA AND JOSH SHARE THEIR STORY WITH DRS. JENNIFER CONTI, HEATHER IROBUNDA, AND JENNIFER LINCOLN. In today’s newsletter, we’ve got another great news rundown for you, including an infuriating abortion update from Georgia and an explainer on the battle between former British Prime Minister Liz Truss and Latuca Sativa. Lettuce get into it. 🥁 Starting a lettuce farm, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONDefining a person: Georgia’s abortion ban, which makes terminating any pregnancy after six weeks illegal, includes another “uniquely dangerous” provision that grants an embryo or fetus full legal rights and recognition as a person. This makes Georgia the first state to enact a “fetal personhood” law post-Roe—and if far-right politicians have their way, it won’t be the last. (Men’s rights groups, like this one in Boston, are also on the fetal-personhood train.) Why should we be concerned? For one thing, as Alanna Vagianos writes for Huffington Post, “Abortion and miscarriage are medically indistinguishable.” This means that under Georgia law, pregnant people could be investigated and even imprisoned both for seeking abortion care and for seeking care while suffering a miscarriage. It only takes one criminal trial to establish enough precedent for more states to attempt similar personhood laws criminalizing abortion and unintended pregnancy loss. While other states are preventing patients from seeking care, this law goes the farthest by turning abortion into a potential felony. If you’re in Georgia you can vote for abortion-rights candidates who will fight this in the state legislatures. Also consider donating to Access Reproductive Care - South East, which works specifically to help those seeking abortions and other kinds of care in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Tennessee. To echo the words of Amanda Zurawski: It’s not enough to be angry. We must act. Iranian 👏🏼 women 👏🏼 : Last weekend, Iranian rock climber Elnaz Rekabi competed in international competition without her hijab, which is mandatory for all female athletes representing Iran in international events. Shortly after the competition ended, Rekabi was “out of contact” according to some of her relatives after she told them she was meeting with an Iranian official. Rekabi later posted to Instagram that her hijab had fallen off inadvertently and she didn’t have time to put it back on before her scheduled climb. She made a similar statement on Iranian television. But many believe that these statements were made under duress and that Rekabi was forced to apologize in order to ensure her safe return to Iran. She returned to Tehran Thursday, and was greeted as a hero by crowds who have been protesting the Iranian government for weeks; the international community and several sports governing bodies remain fixated on Rekabi and her safety. ELNAZ REKABI (SCREENSHOT VIA INSTAGRAM) Lettuce chat about Britain: Liz Truss has resigned from her post as British Prime Minister after a mere 44 days on the job. (Maybe quiet quitting just wasn’t enough.) With England facing an economic and energy crisis, Truss said, “I cannot deliver the mandate on which I was elected by the Conservative party.” But there is a mystery at the heart of this political issue; lettuce investigate. It seems that after The Economist joked that Truss’s tenure would be less than the lifespan of a head of lettuce, The Daily Star set up an actual competition, and today several outlets confirmed that the lettuce lasted longer. So here’s my question: Not a single head of lettuce I’ve ever purchased has lasted more than three days no matter what I do to preserve it. It just doesn't make sense! Is it a conspiracy? Is it a statement on the resilience of British agriculture? Is it a cake designed to look like lettuce? (Spoiler: it’s none of the above. It was only a six-day-old lettuce. That’s still pretty impressive.) AND:

ONE MORE THING!Have you gotten your tickets to our fall event yet? PRESENTED BY  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

My Pregnancy vs. the State of Texas

October 17, 2022NEWSLETTER,FEATURED STORY

A home for modern feminism

“The loss of my daughter was inevitable. What happened next was not.”

BY AMANDA ZURAWSKI

I was 18 weeks pregnant when I knew something was wrong. My body was leaking thick and yellowish discharge, and my pelvis felt what I could only describe as abnormally “open.”

A shockingly brief examination later, I was diagnosed with an “incompetent cervix”—a condition in which the cervix prematurely dilates, usually during the second trimester of pregnancy and often leading to premature birth.

The loss of my daughter, I was told, was inevitable. What happened next was not.

It was evident from the moment my doctor saw my bulging amniotic sac that this was not a question of if I would lose my baby—the baby my husband and I wanted so badly and had worked for 18 months with the help of science and medicine to conceive. It was a question of when.

If we had conceived the previous year when we began our journey with infertility, or if we lived in a different state, my healthcare team would have been able to treat me immediately and end my doomed pregnancy as soon as possible, without risk to my life or my health. I wouldn’t have had to wait in anguish for days for the inescapable ill fate that awaited. But this was August 23, 2022, in the state of Texas, where abortion is illegal unless the pregnant person is facing “a life-threatening physical condition aggravated by, caused by, or arising from a pregnancy.” Somehow, any medical help to make the horrific inevitability of losing my beloved child 22 weeks early less difficult qualified as an illegal abortion.

My doctor outlined the roadmap in no uncertain terms: I could wait however long it took to go into labor naturally, if I did at all, knowing that my baby would be stillborn or pass away soon after; I could wait for my baby’s heartbeat to stop, and then we could end the pregnancy; or—most alarmingly—I could develop an infection and become so sick that my life would become endangered. Not until one of those things happened would a single medical professional in the state of Texas legally be allowed to act. It was a waiting game, the most horrific version of a staring contest: Whose life would end first? Mine, or my daughter’s?

I knew I was going to lose my baby. And I knew it could be days—or weeks—of living with paralyzing agony before we could move forward.

People have asked why we didn’t get on a plane or in our car to go to a state where the laws aren’t so restrictive. But we live in the middle of Texas, and the nearest “sanctuary” state is at least an 8-hour drive. Developing sepsis—which can kill quickly—in a car in the middle of the West Texas desert, or 30,000 feet above the ground, is a death sentence, and it’s not a choice we should have had to even consider. But we did, albeit briefly.

Instead, it took three days at home until I became sick “enough” that the ethics board at our hospital agreed we could legally begin medical treatment; three days until my life was considered at-risk “enough” for the inevitable premature delivery of my daughter to be performed; three days until the doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals were allowed to do their jobs.

By the time I was permitted to deliver, a rapidly spreading infection had already claimed my daughter’s life and was in the process of claiming mine.

I developed a raging fever and dangerously low blood pressure and was rushed to the ICU with sepsis. Tests found both my blood and my placenta teeming with bacteria that had multiplied, probably as a result of the wait. I would stay in the ICU for three more days as medical professionals battled to save my life.

Friends visited every night. Family flew in from across the country. I didn’t realize until nearly a month later that my doctors, nurses, and loved ones feared I was going to die.

We still don’t know the extent of damage the wait or the infection had on my body. I’m facing months of procedures and tests to know whether my eggs or my reproductive system were permanently harmed. In fact, later this week I’m having surgery to remove the massive amount of scar tissue plaguing my uterus as a result of the infections. We don’t know yet whether the baby we want more than anything will ever be possible.

Everything that happened after my cervix dilated was avoidable, and it never should have happened. What’s worse is I’m not the only one. This will happen to many women—of all races, all ethnicities, all ages, all across the country—if we don’t fight back.

When the six-week abortion ban in Texas passed last year and Roe vs. Wade was overturned this year, I was furious. But as someone who was then desperately trying everything I could to have a child, I never imagined it would impact me personally. I didn’t realize then the extent to which these laws would truly restrict a woman’s right to make the right decisions for herself, her body, and her future children. I didn’t realize the laws I was angry about would soon prevent me from safe access to healthcare. I didn’t realize these laws would directly prevent doctors from being able to protect their patients in so many ways.

But it’s not just me, and it’s not just Texas. As more states pass similar laws—let alone if members of Congress enact a federal ban on abortion—my story will become the norm. The number of people who will be hurt will be too much to bear, and we have to do something to stop it.

Being angry isn’t enough. To enact change, we must vote and make sure our elected officials know that this is not okay and we will not allow it.

We named our daughter Willow—after the tree that’s known for its ability to withstand adversity and fight against harsh conditions. With our Willow, we’ll show our strength and we will fight.

Amanda Zurawski lives in Texas with her husband, Josh, whom she met in preschool in their home state of Indiana, and their dogs Paisley and Millie.

Stay tuned for more United States of Abortion Stories. And read more here about the medical facts in Amanda’s case.

For abortion access resources and to create a voting plan for the 2022 midterm elections, visit iwillharness.com/abortion.

Video Credits

Director: Amy Elliott

Editor: Ellen Callaghan

DP: Pat Blackard

Camera: Tony Lopez

Audio: Chris Kupeli

Field producer: Karen Bernstein

Music: “Come On Doom, Let’s Party”

Written and performed by Emily Wells

Courtesy of Thesis & Instinct

By arrangement with Terrorbird Media

![]()

This film is a project of The Meteor Fund, and produced in partnership with Harness; with support from Pop Culture Collaborative.

"You Can't Just Tell Someone to Go Home and Pass an 18-Week Fetus. That's Not Safe."

October 17, 2022FEATURED STORY

A home for modern feminism

The doctors behind Obstetricians for Reproductive Justice break down the medicine behind Amanda’s case—and what should have happened

BY MEGAN CARPENTIER

Amanda’s case highlights a key problem about being pregnant in an anti-abortion state in post-Roe America. Vague laws that prioritize the “life” of even a non-viable fetus above the health or life of the person carrying it prevents doctors from providing crucial care in dangerous and life-threatening situations.

That’s because, until September 2021, there was one red line in the law that even the most anti-abortion state legislators could not cross: There had to be exceptions to any and every abortion restriction, even after fetal viability, “for the preservation of the life or health of the mother.”

But last year, when the U.S. Supreme Court allowed the state of Texas to implement its ban on abortions after six weeks—10 months before it overturned Roe v. Wade—it allowed the state to set a new standard.

Under Texas’ S.B. 8, the only time an abortion might be allowed after cardiac activity is detected would be in the case of a “medical emergency”…which the statute does not define. (Another section of the state’s abortion law does define a medical emergency as a condition that “places the woman in danger of death or a serious risk of substantial impairment of a major bodily function,” though medical providers and lawyers say it’s unclear whether it applies to S.B. 8 and notes that a woman’s health is a better standard.) But because S.B. 8 created a private right of action, even a doctor who can absolutely prove there was a medical emergency would still have to go to court to make their case if sued.

These legal burdens made the situation for Amanda’s doctors untenable. Her condition was likely to cause a “medical emergency,” but they couldn’t treat it as one until it became much more dangerous for her.

Drs. Jenn Conti, Heather Irobunda, and Jennifer Lincoln of Obstetricians for Reproductive Justice have spent time with Amanda and her husband. They sat down with The Meteor to explain the medical facts, and what patients are facing.

Tell us more about Amanda’s diagnosis. What is an “incompetent cervix” and how common is it?

Dr. Heather Irobunda: Cervical insufficiency (or incompetency) happens in about 1% of all pregnancies. However, it happens in about 20% of people who end up having miscarriages [in the second trimester].

Dr. Jennifer Lincoln: By definition, this is a painless cervical dilation, as opposed to typical preterm labor or labor, where you have contractions and it hurts. With cervical insufficiency, you don’t know, or there might just be these vague symptoms like Amanda had, where she’s like, “Something just doesn’t feel right.”

Dr. Irobunda: Sometimes a patient will come in for a routine ultrasound around 20 weeks, and then we may notice that their cervix is shortened or is dilated.

Dr. Lincoln: Sometimes what we’ll see is a cervix that is so completely shortened that it’s non-existent anymore, and it’s also dilated. Or, when we look in the vagina with the speculum, all we see is the amniotic sac because it’s basically prolapsed down past where the cervix is. That was the case for Amanda when she went in.

Dr. Irobunda: It can happen so quickly: You can evaluate a patient a week or a few days before and everything looks fine. And then all of a sudden, your patient comes back in and is like, “I feel, like, a lot of pressure. Things feel weird. Can you check me out?” And then their cervix can be completely dilated and there’s no real reason.

Dr. Lincoln: But, as you can imagine, the term “cervical incompetence,” like many obstetric terms we have, is a really terribly guilt-producing word.

What is the normal course of treatment?

Dr. Irobunda: What we can do depends on how long the cervix is. If the cervix is just shortened and not open, we can do something called a rescue cerclage, which is a stitch we basically put in the cervix to try to keep the cervix closed until term. But if there’s pretty much nothing left and it’s dilated, unfortunately, there’s not much that we can do to close the cervix back up or prevent it from dilating more.

Dr. Lincoln: Sometimes part of the fetus is even in the vagina. Or it’s not possible to treat with cerclage because they’re showing other signs of infection, and if we were then to put a stitch in their cervix and basically sew in an infected bag of water and placenta and fetus, they would be at a much higher risk of having complications and going on to be septic.

Dr. Irobunda: In these cases, this is going to, unfortunately, end up with a baby that will not be alive. Depending on when, there may be the option of waiting and seeing how long it takes for your body to kind of kick the rest of this into gear and deliver the fetus that had passed on (which is called “expectant management” and is more common in earlier miscarriages).

Dr. Lincoln: But you can’t just tell somebody to go home and expectantly wait to pass an 18-week size fetus. That’s not going to be safe for anybody. The risk of infection is so high, especially with an exposed membrane and bag of water in the vagina. And then Amanda’s ruptured.

Dr. Irobunda: In my state, New York, there’s also the option that we can help induce this miscarriage by giving you medications in the hospital while we are monitoring you. Then it would come out of the vagina and we can give you as much pain medication as you need to get through that. And then the other option is to do a procedure called a dilation and evacuation, in which we would sedate you and then we use various instruments to remove what’s left of the pregnancy.

Dr. Lincoln: What should have been done without all these laws is not a difficult question. In a case where you’ve got somebody who has no cervix left, their bag of water was exposed in the vagina for days, now their bag of water is broken, every OB-GYN is trained to know that all of our patients look very stable until the moment they fall off that cliff and they’re not.

You’re talking about sepsis?

Dr. Lincoln: Yes. Patients can go from being healthy and fine to being septic in a matter of an hour. If you walked in like she did, we would say, “We need to move forward with delivery. You are stable now, this could very much change, and so we need to get the infection out of you, which unfortunately means the placenta and the fetus.” And it’s hard because these are people who want the baby. Sometimes you just wish you could leave people alone or say, “Let me give you a few days to decide.” In this particular situation for Amanda, I don’t think any OB-GYN would have felt comfortable doing that.

Dr. Irobunda: The longer that person remains pregnant, number one, it increases the risk of bad outcomes in terms of things like infection, sepsis, bleeding, and hemorrhage. But it also does a lot mentally to that patient and the family, just knowing that this pregnancy is a miscarriage and that it is not going to end well. We need to minimize the suffering of those involved. It’s not right.

What do you see as the long-term effects of these laws that prohibit or inhibit doctors from performing abortions?

Dr. Lincoln: These laws are tying our hands and, eventually, will end up killing patients. When these people say, “Well, there’s an exception so that’s OK,” well, actually, there’s not. The bottom line is that when somebody can go from being healthy to dead in 30 minutes, how are we supposed to wade through all of that with lawyers who have no clue? I guarantee you they are not awake at 2:00 AM.

Dr. Irobunda: It’s really hard to make sweeping laws about things like abortion because all these cases are different. The medicine is not black and white, [and] these laws don’t give anybody any wiggle room. We’re putting people in danger.

Dr. Jenn Conti: These laws affect every aspect of how women’s healthcare is handled from here on out. Once you start criminalizing doctors for doing their jobs, no one is safe—because there’s this paralyzing fear amongst healthcare providers that, if anything goes wrong involving pregnancy, someone somewhere could accuse them of illegal activity. And that’s all that matters in states like Texas: an accusation of guilt.

What would your advice be for other women in these circumstances?

Dr. Conti: If you’ve experienced post-Roe harm, I first want to offer my sympathy to you, because you didn’t deserve that.

If you want to share your story as a way of giving yourself a voice and fighting back, you can head to our website and use the contact form at the bottom of the page to either share anonymously or indicate that you are interested in becoming part of future ORJ storytelling projects.

You can read Amanda’s full story, in her own words, here. Stay tuned for more United States of Abortion stories.

For abortion access resources and to create a voting plan for the 2022 midterm elections, visit iwillharness.com/abortion.

Megan Carpentier is currently an editor at Oxygen.com and a columnist at Dame Magazine. Her work has been published in Rolling Stone, Glamour, The New Republic, the Washington Post, and many more.

How #MeToo actually made things better

|

Dear Meteor readers, Today, we’re marking the five-year anniversary of the #MeToo movement going viral—five years since millions of people discovered the work of Tarana Burke, and, prompted by charges against Harvey Weinstein, began to share their own stories of sexual assault. Countless others followed suit. Since then, so much has changed, and so much hasn’t. In today’s newsletter, Samhita Mukhopadhyay talks to feminist author and TV host Zerlina Maxwell, who told her own story years before #MeToo, about the anniversary, and what it actually means to #believewomen. We also share a list of changes we’ve seen in the last five years to fight rape culture. Thankful for Tarana, Shannon Melero  LOOKING BACK“I'm Not Afraid to Keep Talking”Zerlina Maxwell discusses the impact of the #MeToo movement.BY SAMHITA MUKHOPADHYAY  ZERLINA MAXWELL SPEAKING AT A POLITICAL CONVENTION IN LOS ANGELES. (IMAGE BY PHILIP FARAONE VIA GETTY IMAGES) As I began reflecting on the five years since #MeToo went viral, I found myself thinking, maybe surprisingly, of the many years that came before it. I thought about the Take Back the Night marches I attended in college, the organizations that had long been committed to eradicating rape, such as RAINN or the New York and California Coalitions Against Sexual Assault, and anthologies like Yes Means Yes, edited by Jaclyn Friedman and Jessica Valenti in 2008 in which survivors shared their experiences and talked openly about rape culture. After all, Tarana Burke, the leader of the #MeToo movement, coined “me too” in 2006. Today we celebrate the anniversary of a breaking point: the moment it went from a conversation in the margins to one that couldn’t be ignored. But survivors have been coming forward with their stories for a long time, and we wanted to take today to reflect on the work that came before 2017 and the work that lies ahead. I knew exactly who I wanted to talk to in honor of today’s anniversary: my dear friend, feminist, anti-rape advocate, writer, Mornings with Zerlina on SiriusXM, and author of The End of White Politics, Zerlina Maxwell.

Samhita Mukhopadhyay: One of the first conversations we ever had with each other over 10 years ago, was bonding over being survivors. Zerlina Maxwell: I remember; it was in that bar in Brooklyn. We talked about how we both had issues sleeping after our assaults. And we cried, and we held hands. I think it was like meeting a “friend soulmate” but also meeting someone with the same scars on our souls. It was a connection through a shared pain and deep pain. By the end of the night, we were best friends. How did you first come forward with your story, and what was that experience like? I hadn’t really called it anything yet…and when I explained what happened to someone the day after it happened, their answer back to me was: “That sounds like sexual assault.” So I went to the hospital to officially report it, and the police also responded to me: “What you describe is a sexual assault.” So for me, I think it was getting other people to say it to me. [That’s] when it became real. I knew something bad happened to me right away and was really numb but hearing people call it sexual assault helped me begin processing the trauma. I think it happens differently for everyone. And sometimes it can take a really long time because you’ve tried to probably block it out and move on and pretend it didn’t happen at all, or maybe that it was just some confusing thing. And it’s the process of coming to terms with what happened: Something really did happen, and now my life would never be the same again. It was kind of world-shattering. But I think what broke me more than the actual assault was the people who didn’t believe me. That’s what bothered me the most. Because I always felt like I’m a very trustworthy person. I really don’t lie. I just try to be honest about stuff, and for people to be like, “I don’t believe that happened to you,” that broke my spirit. I was lost for a few years and a shell of the person I was before or who I am today. The impact of the victim blaming is actually what broke me. I don’t think people really recognized how traumatizing that part of it could be. And I really broke. I fell all the way apart.  WOMEN IN AMSTERDAM PROTESTING SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN THE WAKE OF A DUTCH METOO SCANDAL. (IMAGE BY PAULO AMORIM VIA GETTY IMAGES) This was in the early 2010s, long before #MeToo. In 2014, there was a similar hashtag, #YesAllWomen, which women were using to share their experiences with sexual assault. How did that make you feel? Validated. It made me feel less alone. That's one of the reasons I wanted to talk about it: Because I knew it wasn't just me. One of the things I [realized] was this idea that we believe that good things happen to good people and bad things happen because you did something bad, or bad circumstances happen because of a mistake that you made and a choice that you made. But that is bullshit. And that was one of the big realizations I had, like, “Why is it that people are blaming me for what happened? Why?” I didn't understand that. I was like, "I didn't do anything. I didn't make choices that led to that.” And through that [questioning], I gained a level of courage. Because once I felt like I figured it out, I was like, “I found the matrix: [it was] rape culture.” The right criticized #BelieveWomen as ignoring evidence and facts. We know that was a disingenuous argument because no one ever meant, “Believe all women no matter what the facts are.” What do you mean when you say it? When I’m saying you’re believing somebody as a default position, what you’re defaulting to at that moment is empathy and compassion. I always tell kids on college campuses; if you don’t remember anything I said today about rape culture, I want you to remember one thing. And it’s that if somebody comes to you and they say, “I think,”—which is usually what they say, “I think I’ve been sexually assaulted,” and not, like, “I have been”—you say in response: “I am sorry. How can I help?” That’s all you’re going to say. You’re not going to say, “Are you sure?” You’re not going to say, “Oh, were you drinking?” You’re not going to say, “What were you wearing?” All of those things. You’re not going to say any of that. You’re just going to say, “I am sorry that happened to you. How can I help?” That’s all you’re going to say. You don’t have to make a judgment call at that moment about a verdict or about the case. People get too caught up in that. Besides this idea that people have, “Well, I don’t want to believe without evidence,”—I always like to remind them that in the law, testimony is actually evidence. Sure, there are other types of evidence that you can use to corroborate, and certainly, physical evidence is helpful but not always present in cases like this. But testimonial evidence is evidence. And I want to live in a world where somebody’s account of what happened to them is taken seriously and not shot down. In 2013 you were on Fox News. You made a statement and it turned into a... I mean, it was a zoo of getting attacked. So walk us through what you said on the air. What happened? Fox called me to do a segment. The Colorado state legislature was debating a law that would legalize concealed carry on college campuses. And I was like, “That’s not a good idea.” And one of the people that testified was talking about how she was sexually assaulted on a campus in a place where there weren’t guns allowed. And if she had had her gun, she would’ve been able to defend herself. And so the premise of the segment on hand was, “What’s wrong with the people in Colorado? Why won’t they let women defend themselves with guns…that they can carry everywhere to prevent sexual assault?” And my argument in the segment was, I don’t want or need a gun to not be raped. There’s nobody jumping out of the bushes. It’s the people that you know, your family members and your friends and your intimate partners, classmates, and your colleagues who [rape you]. And so I reframed it in the segment and I said, “Don’t tell me I need a gun. Tell men not to rape.” And after the segment, I got death threats and rape threats. People were like, “What do you mean, teach men not to rape??” And I was like, you have to start teaching people about consensual sex, affirmative consent. And men are not being taught that. They’re being taught that women are literally objects that they’re supposed to dominate. And if they can liquor them up to make it easier, then that’s what they are encouraged to do through popular culture. And that’s resulting in real-world harm. And I just wanted to reframe the conversation away from the things that women are always told they need to do to prevent their own assault. I hate that shit.  PHOTO BY HEATHER HAZZAN Samhita Mukhopadhyay is a writer, editor, and speaker. She is the former Executive Editor of Teen Vogue and is the co-editor of Nasty Women: Feminism, Resistance and Revolution in Trump's America and the author of Outdated: Why Dating is Ruining Your Love Life, and the forthcoming book, The Myth of Making It.  Five Ways #MeToo Changed UsThe backlash to #MeToo has been fierce, and yes, too few perpetrators have been genuinely punished. But our refusal to normalize sexual assault and sweep abuse under the rug is progress. Here are five signs of forward movement over the last five years: We listened to victims. They did the incredible labor of telling us they would no longer be ignored. Consider:

Hollywood started to create new ethical and legal standards. Today, many sets have intimacy coordinators to help with sex or other vulnerable scenes. But they weren’t a standard fixture on film/TV sets until 2018. The first series to hire an intimacy coordinator was HBO’s The Deuce that year. The post #MeToo era also saw the creation of the Hollywood Commission, which has cataloged the various kinds of abuse and discrimination happening behind the camera and offered solutions on what needs to change. Long-time predators were brought to justice. After years of accusations, lawsuits, and whispers, we have finally begun to see the accused brought to justice. Among those held accountable by the legal system thus far are R. Kelly, Bill Cosby, Harvey Weinstein, and soon, Kevin Spacey, along with enablers like Ghislaine Maxwell. The shroud of money and power that once protected the misdeeds of all of these people is slowly fading. Individual states took steps to help survivors of workplace harassment. Fifteen states put limits on non-disclosure agreements as they pertain to sexual harassment claims in the workplace, with the broadest limits implemented in the state of Washington. Where NDAs were once used to silence victims of harassment or assault, they now have little to no strength to stop a victim from coming forward against their employer. #MeToo became a global movement. Activists worldwide brought the message of #MeToo to their countries and created a worldwide movement that fundamentally changed how sexual assault is discussed, thought of, and legislated. People in Turkey, Ukraine, Egypt, and across South America broke their silence online, marched, testified, and refused to be judged in their pursuit of justice. On an episode of the podcast Because of Anita, Tarana Burke said, “I think that the way movements work is that you have people who put their heads down and grind and grind and grind and grind and grind. And then you have a moment that brings it all together and advances us a little further than we would have advanced on our own.” We’re all so grateful for the grind that got us further than we thought possible. Let’s keep going.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

“I'm Not Afraid to Keep Talking”

BY SAMHITA MUKHOPADHYAY

As I began reflecting on the five years since #MeToo went viral, I found myself thinking, maybe surprisingly, of the many years that came before it. I thought about the Take Back the Night marches I attended in college, the organizations that had long been committed to eradicating rape, such as RAINN or the New York and California Coalitions Against Sexual Assault, and anthologies like Yes Means Yes, edited by Jaclyn Friedman and Jessica Valenti in 2008 in which survivors shared their experiences and talked openly about rape culture. After all, Tarana Burke, the leader of the #MeToo movement, coined “me too” in 2006.

Today we celebrate the anniversary of a breaking point: the moment it went from a conversation in the margins to one that couldn’t be ignored. But survivors have been coming forward with their stories for a long time, and we wanted to take today to reflect on the work that came before 2017 and the work that lies ahead.

I knew exactly who I wanted to talk to in honor of today’s anniversary: my dear friend, feminist, anti-rape advocate, writer, Mornings with Zerlina on SiriusXM, and author of The End of White Politics, Zerlina Maxwell.

Samhita Mukhopadhyay: One of the first conversations we ever had with each other, over 10 years ago, was bonding over being survivors.

Zerlina Maxwell: I remember; it was in that bar in Brooklyn. We talked about how we both had issues sleeping after our assaults. And we cried and we held hands. I think it was like meeting a “friend soulmate” but also meeting someone with the same scars on our souls. It was a connection through a shared and deep pain.

By the end of the night, we were best friends. How did you first come forward with your story, and what was that experience like?

I hadn't really called it anything yet…and when I explained what happened to someone the day after it happened, their answer back to me was: “That sounds like sexual assault.” So I went to the hospital to officially report it, and the police also responded to me: “What you describe is a sexual assault.” So for me, I think it was getting other people to say it to me. [That’s] when it became real. I knew something bad happened to me right away and was really numb but hearing people call it sexual assault helped me begin processing the trauma.

I think it happens differently for everyone. And sometimes it can take a really long time because you've tried to probably block it out and move on and pretend it didn't happen at all, or maybe that it was just some confusing thing. And it's the process of coming to terms with what happened: Something really did happen, and now my life would never be the same again. It was kind of world-shattering.

But I think what broke me more than the actual assault was the people who didn't believe me. That's what bothered me the most. Because I always felt like I'm a very trustworthy person. I really don't lie. I just try to be honest about stuff, and for people to be like, "I don't believe that happened to you," that broke my spirit. I was lost for a few years and a shell of the person I was before or who I am today. The impact of the victim blaming is actually what broke me. I don't think people really recognized how traumatizing that part of it could be. And I really broke. I fell all the way apart.

This was in the early 2010s, long before #MeToo. In 2014, there was a similar hashtag, #YesAllWomen, which women were using to share their experiences with sexual assault. How did that make you feel?

Validated. It made me feel less alone. That's one of the reasons I wanted to talk about it: Because I knew it wasn't just me.

One of the things I [realized] was this idea that we believe that good things happen to good people and bad things happen because you did something bad, or bad circumstances happen because of a mistake that you made and a choice that you made. But that is bullshit. And that was one of the big realizations I had, like, “Why is it that people are blaming me for what happened? Why?” I didn't understand that. I was like, "I didn't do anything. I didn't make choices that led to that.”

And through that [questioning], I gained a level of courage. Because once I felt like I figured it out, I was like, "I found the matrix: [it was] rape culture."

The right criticized #BelieveWomen as ignoring evidence and facts. We know that was a disingenuous argument because no one ever meant, “Believe all women no matter what the facts are.” What do you mean when you say it?

When I'm saying you're believing somebody as a default position, what you're defaulting to at that moment is empathy and compassion. I always tell kids on college campuses; if you don't remember anything I said today about rape culture, I want you to remember one thing. And it's that if somebody comes to you and they say, "I think,"—which is usually what they say, "I think I've been sexually assaulted," and not, like, "I have been"—you say in response: "I am sorry. How can I help?" That's all you're going to say. You're not going to say, "Are you sure?" You're not going to say, "Oh, were you drinking?" You're not going to say, “What were you wearing?" All of those things. You're not going to say any of that. You're just going to say, “I am sorry that happened to you. How can I help?” That's all you're going to say.

You don’t have to make a judgment call at that moment about a verdict or about the case. People get too caught up in that. Besides this idea that people have, “Well, I don't want to believe without evidence,”—I always like to remind them that in the law, testimony is actually evidence. Sure, there are other types of evidence that you can use to corroborate, and certainly, physical evidence is helpful but not always present in cases like this. But testimonial evidence is evidence. And I want to live in a world where somebody's account of what happened to them is taken seriously and not shot down.

In 2013 you were on Fox News. You made a statement and it turned into a... I mean, it was a zoo of getting attacked. So walk us through what you said on the air. What happened?