The Year of "Mar-a-Lago Face"

It’s time to talk about the campy aesthetic of Trumpworld women.

By Nona Willis Aronowitz

What, exactly, is the “MAGA look”? Like pornography, you know it when you see it: It’s an exaggerated performance of traditional gender norms so common among the women of Trumpworld that it’s known as “Mar-a-Lago face.” It may involve Botox, cheek implants, fake eyelashes, injected lips, glossy waves, and a surfeit of bronzer. Think of the over-the-top looks sported by DHS Secretary Kristi Noem, strategist Kimberly Guilfoyle, and former RNC chair Lara Trump (as well as a few rightwing men, like Florida congressman Matt Gaetz).

What does this increasingly ubiquitous look tell the world about gender and power? What do these women gain from transforming themselves? And is it even worth talking about, given the recent onslaught of horrors? I called writer Inae Oh–who consulted historians, sociologists, and plastic surgeons for the best piece I’ve read on the subject, a Mother Jones feature–to ask about the deeper meaning of the trend.

Nona Willis Aronowitz: Before we get into it, what would you say to those who think focusing on people's (and mostly women's) looks is besides the point—that we should solely focus on their terrible actions? Are we just using the same weapons against them that people have always used against women?

Inae Oh: I would say, “I hear you!” But I would also argue that it is a mistake to dismiss the issue as superficial–the aesthetics of fascism have long been preoccupied with restoring gender norms and ideas of perceived "perfection," something we clearly see playing out both in the aesthetics and politics of MAGA.

Believing that this is besides the point also risks misunderstanding the forces that animate Donald Trump: appearance over substance, one's TV performance over policy, propaganda vs. reality. These are some of the most powerful people in the United States, imposing some of the most consequential policies in decades. Their deliberate choices are worthy of interrogation.

Kristi Noem has been such a central figure in the last couple of months. What does her visual presence signal to you?

Her aesthetic choices dovetail very nicely with the administration’s promise to take mass deportations to an unprecedented level. This is a priority for them, and the face of that priority really matters to Trump. I think there’s a reason why it’s not Stephen Miller out there. Trump has explicitly stated to Noem, “I want your face in the ads.” She’s gone through a dramatic transformation from when she was South Dakota's governor to what she looks like now.

Basically, she’s a woman with a look that’s very rooted in conservative, traditional ideas of what a woman should look like: long, flowing hair, heavy makeup, form-fitting dresses–but at the same time she has that baseball cap on and she’s employing incredibly harsh and cruel and aggressive policy. That supposed contradiction is intentional. Her look also provides cover for the brutal policies that are being implemented across the country. [After Sen. Alex Padilla was forcibly removed from a press conference], Rep. Anna Paulina Luna (R-Fla.) defended Noem and described her as “the most delicate, beautiful, tiny woman.” She said, “What actual testosterone dude goes in and tries to break Kristi Noem?” All of a sudden, she’s a defenseless woman.

There are certainly some precedents to the MAGA look in conservative politics and media; Fox News hosts of the last couple of decades come to mind. What’s different now?

I mean, it’s Donald Trump. It’s turbo-charged now. This is a man who literally has a background in reality TV. This is a man who doesn’t really know policy, who only cares about how you appear and how you can sell a certain idea. And [Trump’s taste is] extremely garish. Trump is notorious for his love of gold. It can seem so tacky to me, personally, but to him, it signifies wealth and power. When you have the most powerful man in the world having those priorities, people use these visual signifiers to gain power and favor.

Is this really just a rightwing thing? Lots of people, particularly women, feel pressure to conform to a certain look, which increasingly includes cosmetic enhancements.

I’m also a woman in this world, and I absolutely partake in our capitalist beauty standards. Plenty of people on the left, people who are my friends, are also opting to undergo procedures like Botox. You have Gen Z on TikTok being very open about the work they’ve done on their faces. For the longest time, plastic surgery was not accessible to the masses…As it has gotten cheaper and more normalized, people have become more open about it, like how Kris Jenner documented her facelift.

So it’s not completely divided by politics, but I think what’s happening on the right is a bit different. It’s such an appeal to tradition, whereas on the left, there’s more of an embrace, politically and culturally, of gender fluidity. And there’s more of an embrace of sustainability with companies like Reformation and green-friendly makeup, whereas on the right, that’s not at all a concern; it’s all about excess.

Men are secondary to this phenomenon, but they’re certainly in the mix. How do you think the MAGA aesthetic plays out when it comes to masculinity?

Pete Hegseth, to me, is the male equivalent of Kristi Noem. Men like him wear these bright-colored blue suits that don’t just fade into the background, and are supposed to be a sign of patriotism. Their shoulders are extremely broad, whether that is natural or not. Their chins, their jaws are very chiseled. It’s such an aggressive, cartoonish way to represent gender norms, and that absolutely plays into this Donald Trumpian idea of a powerful man. It’s not as ridiculous as the women, maybe because they don’t wear as much makeup. Do these rightwing men want to be known for caring about their looks? Absolutely not. They would see that as a sign of weakness. But there have been reports of Hegseth installing a makeup room in the Pentagon. [“Totally fake story,” Hegseth responded on X.] He puts that same importance on visuals and the message, rather than budgets and policies.

The Evolution of the Rightwing Lewk

Conservative politics has always demanded that women perfectly embody the gender norms of the era.

1970s: Phyllis Schlafly

The “godmother of the conservative movement” intentionally wore ultra-feminine outfits–preppy pastels, skirts in the pantsuit era, and pussy bows–while attacking the Equal Rights Amendment.

Early ‘00s: Gretchen Carlson

Famously crowned Miss America in 1989, she was one of many prominent “Fox blondes.” (In a twist, she was later key to taking down Fox News CEO Roger Ailes for sexual harassment.)

2008: Sarah Palin

Known for her sexy soccer mom look (with a rifle!), she ushered in a departure from the gender-neutral appearance of most female politicians at the time.

2025: Kristi Noem

Tasked with carrying out some of Trump’s cruelest policies, she is the platonic ideal of Mar-a-Lago face: pillowy lips, blinding white teeth, long wavy hair, and lots of makeup.

How Much Is Your Kid Worth?

July 10, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, This weekend my child is attending her first day of soccer camp, and I’m so nervous and excited you’d think we were attending the NWSL draft. But save this email because one day we might be! In today’s newsletter, we cover a sensitive subject: money. Plus, fun news for movie lovers and your weekend reading list. From your newly minted hot soccer mom, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONTell your toddler to get a job: We need to talk about taxes. Don’t scroll away from me, this is important! As part of the new tax package passed last week in the “Big Beautiful Bill,” a number of permanent changes have been made to the child tax credit. And for millions of children, those changes are bad. Here’s how it breaks down: For some, the dollar amount will actually increase; if you qualify for the full credit, you get $2,200, up from $2,000. But under the new changes, 2.7 million fewer children qualify than did last year. Unsurprisingly, non-citizens are targeted; to receive the full amount, one parent in the household must have a Social Security number—which was not the case in previous years. The child must have one as well and have lived six months or more in the U.S. with their parent or guardian. (A family headed by an undocumented single parent would not receive the credit at all, even if the child is a citizen.) In failing to write any new protections around eligibility–a dire oversight if you’re actually trying to help more families–the bill inadvertently raised income requirements. A two-parent household with two children has to earn a minimum income of $41,500 to qualify. (This minimum basically didn’t exist in 2024.) If your household earns less than the qualifying income, you may get around $1,700 per child or, in some cases, no money at all. (There is still a maximum, where joint filers making more than $400,000 receive less of the credit.) These numbers change based on other filing factors, but the bottom line is this: Ultimately, about 19 million children are now blocked from receiving the full amount because their family's income is too low. The Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University found that 60 percent of children of single mothers will not be able to receive the full credit for the 2026 tax season. (That number goes down to 41 percent for children of single fathers. Hm.) When you pair these changes with the cuts to SNAP, early childhood education, and Medicaid, the picture of just how much the government hates low-income families becomes clear. “They don’t give a fuck about us, man” was the first text I received when the BBB passed. Quite a few of my friends and family members are single parents, and while $2,000 once a year didn’t fix all of their problems, it had been a life raft that they looked forward to and depended on. Without it, they’ll be scrambling to cover things like school supplies or daycare payments. I couldn’t even consider having a second child (and just to be clear, Mom, I’m not) because the financial strain would be so great and the safety net so small. Republicans love to tell everyone to have more children, but they’re passing policies that ensure only certain kinds of families will have the financial means to do so. There is, surprisingly, a sliver of hope in all this: state lawmakers. States can still tailor their tax codes to provide more robust child tax credit programs, which already exist in some states. If you don’t know your state’s policy or how to advocate for better, the Coalition on Human Needs has a ton of guides. AND:

WEEKEND READING 📚On bloodsuckers: Are we headed for a recession? Only Nelini Stamp and the vampires know the answer. (World Builders Club) On pointe: When a ballerina gets pregnant, it often means a huge loss of income. But now dancers are working to change an industry built on their bodies. (Elle) On sportsmen: There are no openly gay or bisexual men competing in America’s professional sports leagues. Why not? (Uncloseted Media)

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

We All Have a Climate Disaster Story

July 8, 2025 Howdy, Meteor readers, It’s Amazon Prime Day, and in case you’ve been adding to cart, remember: it’s just a week-long scam to line Bezos’ pockets without providing meaningful discounts. There are other stores. In today’s newsletter, we’re grieving with the people of central Texas as they navigate an unbearable tragedy. Plus, a glimmer of hope for Planned Parenthood’s Medicaid patients. Thinking of Silvana and María, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONUnforgiving waters: On Friday, a devastating flash flood struck central Texas, washing away homes, vehicles, and much of an all-girls’ summer camp, Camp Mystic. The death toll is over 100 but is expected to rise as rescuers continue searching the Guadalupe River for remains of the deceased. As is often the case when a tragedy of this size occurs, many are wondering what, if anything, could have been done differently to preserve life. According to a timeline compiled by NPR, the National Weather Service (NWS) and the Texas Division of Emergency Management issued warnings of imminent flooding in the area, with alerts upgrading in severity hours before the river started to swell. But some Texas officials are blaming the NWS—an organization that lost 600 workers this year because of Trump’s federal restructuring and funding cuts to its parent, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration—for inadequate warnings. Trump denied the correlation, saying, “This is a 100-year catastrophe.” Well, yes and no. This kind of flooding used to be a 100-year catastrophe, but human behavior and government failures have quite literally changed the game. While there will need to be an investigation to determine if the shortages at NWS (including the fact that a key manager in charge of local warnings reportedly left after cuts this spring) exacerbated the situation, one thing is certain: extreme weather events are becoming more frequent, and this flood’s severity was impacted by worsening climate change. “With a warmer atmosphere, there is no doubt that we have seen an increase in the frequency and the magnitude of flash flooding events globally,” meteorologist Jonathan Porter told the L.A. Times. “The key question is, what did people do with those warnings…What was their weather safety plan, and then what actions did they take based upon those timely warnings, in order to ensure that people’s lives were saved?” Perhaps the loss of life could have been minimized with more evacuations from the area, nicknamed Flash Flood Alley, but it is an inescapable fact that more and more people will die as the Earth continues to warm. And as we’ve seen from the number of young girls swept away by flood waters, it will be the most vulnerable who pay the price. Whether we realize it or not, we’ve reached a point where every single one of us has a climate disaster story. (If you just thought to yourself, I don’t, remember the last two summers were the hottest summers since 1940 and not everyone lived to tell the tale. You’ve lived through at least two climate disasters.) Maybe you lost everything fleeing Hurricane Maria—or found yourself breathing poor air in New York City as smoke from the Canadian wildfires made its way south. Either way, living through or dying from a natural disaster is becoming unremarkable. The time for climate denialism is long gone. If the government is unwilling to take the financial and political steps needed to slow climate change, the “100-year catastrophes” will continue to mount. How you can help survivors in Texas: AND:

WHAT REMAINS OF A HOSPITAL INSIDE EVIN PRISON. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Does America Deserve a Party?

July 3, 2025 Hey there, Meteor readers, We are off tomorrow to partake in the celebration of America having cast off its oppressors, only to turn around and oppress in return. Or July 4th for short! Either way, it’s a day off to spend with your loved ones and wonder what’s up with Joey Chestnut. Or sit alone and do some fun feminist reading, Whatever’s clever, babe.  But before we sign off for the long weekend and before we spend all our brain power fretting about the Big Beautiful Bill becoming a reality, we’re taking an optimistic stroll through the news to find the good happening around the country. Plus, we talk to some of our friends about patriotism. Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON (GOOD-VIBES-ONLY VERSION)

MICHIGANDERS BUILDING A WALL OF PLASTIC BOTTLES TO "WELCOME" DONALD TRUMP IN 2016. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

THEY REALLY ATE IN THOSE DRESSES, THOUGH. MAYBE WE BRING THEM BACK FOR AN OLDIES NIGHT GAME. (VIA GETTY)  When, If Ever, Do You Feel Patriotic?(You’re allowed to answer with a middle finger.)  THOSE STRIPES DON'T RUN BECAUSE THEY ARE SECURED IN PLACE WITH AT LEAST THREE KNOTS. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) On an Independence Day only a billionaire could love, and in a time when many Americans feel less free than ever, we asked seven women their interpretation of patriotism. There is something in the American psyche that urges us towards problem-solving and exuberant creativity. We celebrate innovation and resilience, and capability in all forms. I feel pride when I see a person from my nation excel because of their indomitable spirit and resilience. But patriotism is also the bittersweet understanding that I love my place of birth and the culture that accompanied it, despite every instance of it not loving me as it should. It is a reminder that love is an unselfish end in itself. Patriotism has always been an odd concept to me. Maybe it's the Indigenous in me, but pledging loyalty to a government (which is how I view patriotism) always seemed a bit cultish. Particularly as an American, I'll never understand the desire to put my life on the line for a governing power that provides nothing in return (no healthcare, no education, no childcare, no right-to-a-life-of-dignity-or-safety, should I keep going?). I always thought that patriotism was a "if you love this place, let's make it better" type of thing, but from 2017-now, I've learned I'm on a minority-populated island on that one. How am I supposed to feel patriotism for a country that abandons, betrays, imprisons, and kills its patriots? I see patriotism through the same lens as James Baldwin—a profound love for America that requires constant critique, improvement, and accountability. But I don't feel patriotic, because I don't always trust that America will love me back. As a person who thinks in transnational feminism, patriotism is really complicated. I can't see the word outside of its roots in father/fatherland beliefs and values. Patriotism requires borders, policing, control, and exclusion….It has always been tied to supremacist ideals and patriarchal violence, even in defense of positive values, like democracy. Now more than ever, we have to recognize the critical necessity of solidarity beyond borders, of caring for the displaced and the fugitive…And we have to use new words. We've had millennia of patriotism. Maybe use, as so many have suggested before us, matriotism, a love of each other and all living things, rooted mutual care and responsibility, guided by the refusal to glorify war and violence. If the definition of patriotism is devotion to one's country, then one has to love that country even when she is on her knees. That’s when you have to be loyal the most - when she’s hurting. False patriotism waves flags and indulges in jingoistic mantras and empty pronouncements. True patriotism looks upon a nation with eyes wide open and loves her enough to “criticize her perpetually,” as James Baldwin wrote….Yet being a patriot in dark times isn’t easy. When you are born in Puerto Rico, as I was, an island invaded in 1898 by the United States, called trash by its colonial masters, and fighting for self-determination, you understand that. True patriotism doesn’t hide in a corner; it doesn’t die a coward's death. It grows strong enough to change the course of history. My patriotism is my people: It lives within each of us. It thrives when we protect one another from the violence of the state. Patriotism is not allegiance to power—it’s love for those who are targets of the state. It’s the courage to care for each other, especially when our government does not. My only childhood memory that could be categorized as patriotic is this: My grandmother—a second-generation Eastern European who voted in every election from the late 1920s to 2008, when, tired of “that fucking Bush,” she delightedly cast a vote for Obama—would drive me every summer to her home in the Catskills. And when her creaky Oldsmobile crested the hill and the mountains and fields came into view, she would break into “America the Beautiful.” (It lasted forever.) She clearly didn’t mean the government. She meant the literal place she lived: the land and its people, the community she was part of. That seems like as good a definition of patriotism as any to me: to make the place you live, where you have neighbors, live up to its promise.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

An "Attack on Diplomacy Itself" and the Women Left Behind

July 1, 2025 Hi friends— Cindi here, filling in for Nona and Shannon on what is not just a normal Tuesday in end-times America but a birthday blockbuster: Both Princess Diana (who should have been turning 64 today 💔) and Missy Elliott (blowing out 54 candles) were born on this day. Also on this day, back in 1972, the first standalone issue of Ms. magazine was published. That makes it an excellent time to shamelessly plug “Dear Ms.: A Revolution in Print,” which airs on HBO tomorrow. My fellow producers and I hope you get a chance to watch. Meanwhile, in today’s newsletter, everything from wedding-dress tariffs to a fascinating interview about the history of the word “like.” But first, an important piece about the real cost of the Trump administration’s dismantling of a lifesaving State Department office—by a woman who worked there. Xo, Cindi  WHAT'S GOING ONThe U.S. is Abandoning Women’s Rights. The Women it “Honored” Are Paying the Price.BY VARINA WINDER In March 2024, Agather Atuhaire stood on the White House stage, honored for her work as a human rights lawyer and anti-corruption journalist in Uganda. A year later, she was allegedly tortured and brutally assaulted, and left at the Tanzanian border, after being arrested and prevented from attending the trial of an arbitrarily detained politician. The response from the Trump State Department? A four-line statement from the U.S. Embassy in Tanzania calling for an investigation. At the same time, back on Capitol Hill, Secretary Marco Rubio was doubling down on his intention to dismantle the very office that would normally lead the charge on helping Atuhaire—the Secretary’s Office of Global Women’s Issues. The elimination of that office, in which I proudly served for more than a decade, is scheduled to occur this very week. Along with the dismantling of USAID and the Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau, it is a clear signal that the U.S. is regressing wholesale on women’s rights. And governments like Tanzania’s have already taken note of the new latitude they have to do the same.  THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION HONORED WOMEN THIS SPRING, EVEN AS IT PLANNED TO SHUT DOWN THE OFFICE. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Women like Atuhaire—who trusted that American recognition meant American support—now face retaliation with no meaningful backing from the U.S. Our message to human rights leaders is now: we will honor you on our stage—as Rubio did at this year’s International Women of Courage (IWOC) Awards Ceremony—but when you need us most, we will turn our backs on you. More than 200 women from 90+ countries have received this award over the past 19 years. It’s not just a glass plaque and a ceremony; IWOC has been a living commitment to women’s rights - and has long created new opportunities to make meaningful progress, as quiet, coordinated U.S. diplomacy did together with one of Atuhaire’s fellow honorees, preventing a reversal of a ban on female genital mutilation in the Gambia. Now, human rights organizations worldwide question whether association with America makes their staff and beneficiaries targets—rather than protecting them. The very concept of American soft power—our ability to influence through shared values rather than coercion—depends on us standing by those values. The Tanzanian government's alleged willingness to torture and rape a woman the United States honored on its highest stage is a clear sign of just how much the estimation for America’s purported human- rights values has already fallen.  WOMEN IN KENYA WORKING AGAINST GENITAL MUTILATION WITH THE SUPPORT OF UNICEF AND THE WOMEN'S ISSUES OFFICE. (PHOTO COURTESY OF VARINA WINDER) This institutional dismantling of my former office follows the same non-logic of the self-imposed destruction of USAID. This is not about efficiency: our tiny staff is the only dedicated, expert staff on these issues, as a mere 8 percent of State Department bureaus and offices globally have someone with “women’s rights” as a dedicated part of their job, along with an average of nine additional duties. This is not about efficiency or cost savings; our $10 million budget is spent by the Pentagon in the time it takes to watch a YouTube video. This is a coordinated, multi-front attack on women’s rights, the organizations that support them, and the leaders who believe in them. It’s also an attack on diplomacy itself. When we eliminate the infrastructure, the people, and the office that support our values, we don't just lose a dedicated office; we lose credibility and trust. As Senator Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH) said in an SFRC budget hearing with Secretary Rubio in May, “Beijing is making the case that they are a more reliable, credible partner than the U.S.” The path forward requires more than defending the Office of Global Women's Issues - which we each must be calling on the Senate and House to do. It also demands acknowledging that our retreat from human rights leadership has real victims with names and faces and bodies. Atuhaire's brutal rape and torture may have happened in Tanzania, but the failure of accountability is America’s. She trusted us; we failed her. Varina Winder is the former Chief of Staff and senior advisor in the Secretary of State’s Office of Global Women’s Issues. AND:

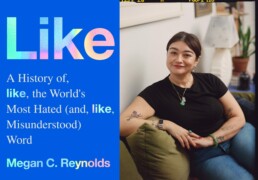

Three Questions About...Like, Words and StuffJournalist Megan Reynolds takes up the most derided word in the dictionaryBY SHANNON MELERO  IT'S JUST LIKE, A REALLY INTERESTING BOOK. (COVER IMAGE COURTESY OF HARPER COLLINS, AUTHOR PHOTO BY CHRIS BERNABEO) Megan Reynolds has always had a way with words, which I experienced firsthand when we worked together at Jezebel, and she told me I could always go to her with any questions. Big mistake, huge! I’ve been pestering her since 2019, and now I have yet another reason: Megan—who has made everything from beach chairs to a really big mall come alive with her deft use of language,—has a new book, Like: A History of, Like, the World’s Most Hated (and, Like, Misunderstood) Word. In it, she traces the word’s origins all the way back to the 1600s, and also writes a love letter to the way women, particularly teen girls, have shaped language. As is our routine, I darkened her door with my queries. So even though women are the ones making fetch happen when it comes to language, this book exists because there’s so much pushback and policing over women’s use of “like.” So I guess my question is, why can’t we just, like, talk how we please? The answer is absolutely “sexism,” but that is a pat response for a situation that is much more nuanced and complex. Sometimes the call is coming from inside the house—for all the professional men out there who write earnest LinkedIn blogs about filler words, power, and corporate communication, there are just as many professional women doing the same thing. The policing comes in many forms, [including] the voice in your own head, but I’d say that it is most evident in the aforementioned blogs on LinkedIn and op-eds in various newspapers around the world. And, if you watch the season premiere of the most recent season of The Kardashians on Hulu, you’ll find the entire family policing Kourtney for saying like, like, all the time. On the surface, any policing of women’s language looks like and definitely is sexist, but underneath, is also the issue of intelligence and whether or not saying “like” a bunch when you talk means you’re not. And yes, this is a battle that both men and women face, but women (I assume) are more concerned with not sounding stupid, whereas men will happily open their mouths and share the first thought that comes to mind. One thing I love is that you described "like" as a word that does a lot of emotional labor, and it's been doing so since before either of us was born. Have you come across a word that is taking on that same labor for the next generation? Or will "like" continue to be a timeless linguistic accessory? Language moves faster than any of us are interested in thinking about, but I think that “like” will never go out of style—and that’s actually good? It means that it’s become an inherent and natural part of speech, and for that, we are forced to stan. However, the youth of today are saying words in ways that I never could have imagined. The meaning of “literally” has changed in recent years due to young people using it in unorthodox ways, and I think a lot of people are pressed about that for reasons unbeknownst. Technically, “literally” does mean just one thing, and often, it’s used in situations that are decidedly not literal. And like “like” can function as an intensifier, “literally” does the same thing. You write about how Serious Feminists™ of the past were also a part of the anti-Like movement. Is there still a sense that we need to sound important if we want to be important? Like with most things in life, the answer depends on the person. I’ve worked with women who are younger than me but much more “professional,” hewing closer to the traditional and generally accepted definition of what that sounds like. To me, this doesn’t matter at all. And because I’m generally not that “professional” by any commonly-held, old-fashioned standard, my aim in writing this book was to communicate that we don’t need to care about this! It doesn’t matter! If someone is or isn’t going to take you seriously in the workplace or anywhere else, I’d wager that they’ve already made that decision before you even opened your mouth, anyway.   FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Three Questions About...Like, Words and Stuff

Journalist Megan Reynolds takes up the most derided word in the dictionary

By Shannon Melero

Megan Reynolds has always had a way with words, which I experienced firsthand when we worked together at Jezebel, and she told me I could always go to her with any questions. Big mistake, huge! I’ve been pestering her since 2019, and now I have yet another reason: Megan—who has made everything from beach chairs to a really big mall to the terrible sport of baseball come alive with her deft use of language,—has a new book, Like: A History of, Like, the World’s Most Hated (and, Like, Misunderstood) Word. In it, she traces the word’s origins all the way back to the 1600s, and also writes a love letter to the way women, particularly teen girls, have shaped language. As is our routine, I darkened her door with my queries.

So even though women are the ones making fetch happen when it comes to language, this book exists because there’s so much pushback and policing over women’s use of “like.” So I guess my question is, why can’t we just, like, talk how we please?

The answer is absolutely “sexism,” but that is a pat response for a situation that is much more nuanced and complex. Sometimes the call is coming from inside the house—for all the professional men out there who write earnest LinkedIn blogs about filler words, power, and corporate communication, there are just as many professional women doing the same thing. The policing comes in many forms, [including] the voice in your own head, but I’d say that it is most evident in the aforementioned blogs on LinkedIn and op-eds in various newspapers around the world. And, if you watch the season premiere of the most recent season of The Kardashians on Hulu, you’ll find the entire family policing Kourtney for saying like, like, all the time.

On the surface, any policing of women’s language looks like and definitely is sexist, but underneath, is also the issue of intelligence and whether or not saying “like” a bunch when you talk means you’re not. And yes, this is a battle that both men and women face, but women (I assume) are more concerned with not sounding stupid, whereas men will happily open their mouths and share the first thought that comes to mind.

One thing I love is that you described "like" as a word that does a lot of emotional labor, and it's been doing so since before either of us was born. Have you come across a word that is taking on that same labor for the next generation? Or will "like" continue to be a timeless linguistic accessory?

Language moves faster than any of us are interested in thinking about, but I think that “like” will never go out of style—and that’s actually good? It means that it’s become an inherent and natural part of speech, and for that, we are forced to stan. However, the youth of today are saying words in ways that I never could have imagined.

The meaning of “literally” has changed in recent years due to young people using it in unorthodox ways, and I think a lot of people are pressed about that for reasons unbeknownst. Technically, “literally” does mean just one thing, and often, it’s used in situations that are decidedly not literal. And like “like” can function as an intensifier, “literally” does the same thing.

You write about how Serious Feminists™ of the past were also a part of the anti-Like movement. Is there still a sense that we need to sound important if we want to be important?

Like with most things in life, the answer depends on the person. I’ve worked with women who are younger than me but much more “professional,” hewing closer to the traditional and generally accepted definition of what that sounds like. To me, this doesn’t matter at all. And because I’m generally not that “professional” by any commonly-held, old-fashioned standard, my aim in writing this book was to communicate that we don’t need to care about this! It doesn’t matter! If someone is or isn’t going to take you seriously in the workplace or anywhere else, I’d wager that they’ve already made that decision before you even opened your mouth, anyway.

The Loss of a "Deeply Personal Freedom"

June 26, 2025  WHAT'S GOING ONYou don’t get to choose: During our morning meeting, while I regaled my colleagues with Sabrina Carpenter theories, a news alert popped up. I swear a group of women hasn’t gone that quiet that fast since Huda’s last crash-out. The alert was that the Supreme Court had published its decision in Medina v. Planned Parenthood. The court ruled 6-3, along ideological lines, that South Carolina’s governor, Henry McMaster, was on sound legal footing when he removed Planned Parenthood South Atlantic from the state’s Medicaid program in 2018. To be clear, South Carolina already outlaws abortions after six weeks, and the Hyde Amendment has long ensured that federal funds cannot be used to reimburse abortion costs anyway. (State funds are a different story.) This case is about punishing Planned Parenthood for its association with abortions, even though its clinics also provide STI screenings, contraception, mammograms, and a number of other vital health services. A 2021 study found that of the millions of women Medicaid recipients who had gone to Planned Parenthood for care that year, 85 percent of them received contraceptive services. That means that when McMaster removed PPSA from the Medicaid program, any Medicaid patient going to one of its clinics lost their healthcare provider, which is why PPSA and one of its patients sued McMaster for violating the “free choice of provider” clause in the Medicaid Act. The lower courts sided with the plaintiffs repeatedly. But the state’s director for the Department of Health and Human Services picked up the fight, and SCOTUS decided that losing access to your health provider is not a violation of your rights. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, who wrote the dissenting opinion, characterized this decision as “stymying one of the country’s great civil rights laws” and Slate points out, associated the majority with white supremacists who once sought to undermine Reconstruction. She deftly laid out what this decision will really do: “It will strip countless other Medicaid recipients around the country of a deeply personal freedom: the ‘ability to decide who treats us at our most vulnerable.’ ”  THE FACE OF A WOMAN WHO IS TIRED OF THE TOMFOOLERY IN THE COURT. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) For patients outside South Carolina, this decision could have a ripple effect. Governors nationwide now have the runway they need to essentially defund Planned Parenthood in their states by blocking the organization’s access to Medicaid funds, which account for one-third of Planned Parenthood’s revenue. At the same time, Republicans are trying to eradicate the organization via the Big Beautiful Bill, which seeks to end Medicaid reimbursements to Planned Parenthood nationally. If passed, the bill “could lead nearly 200 clinics to shutter—90% of them in states where abortion is legal,” independent journalist and Autonomy News cofounder Susan Rinkunas told The Meteor. “If the Trump administration is able to nationalize this Supreme Court decision, people even in protective states would have less access to reproductive healthcare, including abortion.” Bottom line: This decision goes beyond attacking bodily autonomy. Today, the court reaffirmed that being poor, or a woman, or Latine, or Black—the groups that make up the majority of Medicaid users—means that the freedoms and choices enjoyed by everyone else don’t apply to you. If you don’t have the money or the whiteness or the penis to pay for the doctor you want, you’re out of luck. AND:

HOW'S THAT FOR A WARM VENETIAN WELCOME? (GETTY IMAGES)

Three Questions About...Toni MorrisonShe had a whole other job, and she was brilliant at it. BY REBECCA CARROLL  COURTESY OF HARPER COLLINS Toni Morrison wrote some of the greatest literature of all time. It is less known, though, that she also edited some of the greatest literature, and that is what makes Dana A. Williams’s new book, Toni At Random: The Iconic Writer’s Legendary Editorship, such a gift. Williams, a professor of African American literature and the Dean of Graduate School at Howard University, conducted hundreds of interviews (including a handful with Morrison while she was still living) and unearthed letters and conversations between Morrison and the authors she published—among them Toni Cade Bambara, Lucille Clifton, Gayl Jones, and Angela Davis—during her nearly 20 years as an editor at Random House. The result is a thoughtfully reverent, always engrossing, and occasionally juicy narrative that confirms Morrison’s intricate genius, as well as her deep love of Black writers, Black books, and Black language. Rebecca Carroll: What did you learn about Toni Morrison, the editor, that you did not know about Toni Morrison, the writer? Dana A. Williams: I think they intersect, but Toni Morrison as editor was fully involved in the publishing community. I think of Toni Morrison-as-writer as someone writing in isolation—someone writing at their desk, really thinking about her story and her characters. Morrison as editor was everywhere. She was at every party. She was in the design team’s face, sometimes to their dismay. She was on the street trying to find writers, because she really did have to kind of beat the bushes in those early years to identify writers who had not been signed up by other houses. Angela Davis told me that her office was always bustling. There were people in and out all the time, which is part of the reason why, when she was working on a book of her own, she would not go in the office in the same way. One of the beautiful things about this book has been rediscovering books I’ve loved forever, like Toni Cade Bambara’s Gorilla, My Love, now knowing that Morrison played such an integral role in shaping them. Were there books that you returned to in the same way during the process of writing this one? I absolutely went back and reread [Bambara’s] The Salt Eaters because I thought, Now I think I know what’s happening in this book. I love The Salt Eaters. I taught The Salt Eaters, but I never got all of it. The same thing was true of Leon Forrest, who I probably knew more about than any of the authors. All the fiction—the fiction [Morrison edited] was what I was so drawn to to begin with….But the more [Morrison and I] talked, the more she continued to ignore my questions about fiction. She was like the queen of indirection from the beginning to the end, because she never said, “This book really shouldn’t be about the fiction only.” She would drop hints like, “Have you seen Paula’s last book? Now that’s a book. If you’re going to write a book, that’s a book.” She was talking about A Sword Among Lions by Paula Giddings, which was interesting, because it is a biography of Ida B. Wells, and every time I would ask [Morrison] a question about herself, she would say, “I'm not interested in myself.” After spending over a decade on this book, do you have a strong sense now of what Toni Morrison thought made good writing? I kept asking her that question, and she said, “Well, obviously if it’s nonfiction, the argument has to be sound and it has to be compelling, and it has to make the case for the reader in a way that nobody else has made it before.” If she was editing on a topic that she didn’t know as much about, she was literally reading everything about the current conversation to make sure [the author was] moving this argument in a different direction. Editors don't have to do that. For the fiction…I think she was more drawn to experimental writers than to straight beginning, middle, and end writers. She said, “With Gayl Jones, I had to ask questions about characters: What is motivating this character?” With Bambara, she said, “I just needed to make sure that she didn't leave the reader behind, because she’s moving so fast.” I kept thinking, There has to be this kind of crystallized way of saying [what good writing is]. But it was the interrogation. I think that was her distinguishing mark—to publish what stories she wanted to be told, and to let the writer be the writer.  WEEKEND READING 📚On something different: Babe, wake up, a new kind of masculinity just dropped, and it involves Pedro Pascal. (TCF Emails) On the worst trimester: Vox’s podcast, “Unexplainable,” tells the story of geneticist Marlena Fejzo, whose own torturous pregnancy led her to discover both a biological cause and potential cure for morning sickness. (Vox) On evolving the stitch and bitch: Knitting clubs were once a place to complain about your kids and mother-in law (not me I would never), but young knitters are using their craft for a greater good. (Teen Vogue) On what we eat: Food affects everything, but can it really do much about menopause, or are women being sold another fad diet? (Burnt Toast)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Three Questions About...Toni Morrison

She had a whole other job, and she was brilliant at it.

By Rebecca Carroll

Toni Morrison wrote some of the greatest literature of all time. It is less known, though, that she also edited some of the greatest literature, and that is what makes Dana A. Williams’s new book, Toni At Random: The Iconic Writer’s Legendary Editorship, such a gift. Williams, a professor of African American literature and the Dean of Graduate School at Howard University, conducted hundreds of interviews (including a handful with Morrison while she was still living) and unearthed letters and conversations between Morrison and the authors she published—among them Toni Cade Bambara, Lucille Clifton, Gayl Jones, and Angela Davis—during her nearly 20 years as an editor at Random House. The result is a thoughtfully reverent, always engrossing, and occasionally juicy narrative that confirms Morrison’s intricate genius, as well as her deep love of Black writers, Black books, and Black language.

Rebecca Carroll: What did you learn about Toni Morrison, the editor, that you did not know about Toni Morrison, the writer?

Dana A. Williams: I think they intersect, but Toni Morrison as editor was fully involved in the publishing community. I think of Toni Morrison-as-writer as someone writing in isolation—someone writing at their desk, really thinking about her story and her characters. Morrison as editor was everywhere. She was at every party. She was in the design team’s face, sometimes to their dismay. She was on the street trying to find writers, because she really did have to kind of beat the bushes in those early years to identify writers who had not been signed up by other houses. Angela Davis told me that her office was always bustling. There were people in and out all the time, which is part of the reason why, when she was working on a book of her own, she would not go in the office in the same way.

One of the beautiful things about this book has been rediscovering books I’ve loved forever, like Toni Cade Bambara’s Gorilla, My Love, now knowing that Morrison played such an integral role in shaping them. Were there books that you returned to in the same way during the process of writing this one?

I absolutely went back and reread [Bambara’s] The Salt Eaters because I thought, Now I think I know what’s happening in this book. I love The Salt Eaters. I taught The Salt Eaters, but I never got all of it. The same thing was true of Leon Forrest, who I probably knew more about than any of the authors. All the fiction—the fiction [Morrison edited] was what I was so drawn to to begin with….But the more [Morrison and I] talked, the more she continued to ignore my questions about fiction. She was like the queen of indirection from the beginning to the end, because she never said, “This book really shouldn’t be about the fiction only.” She would drop hints like, “Have you seen Paula’s last book? Now that’s a book. If you’re going to write a book, that’s a book.” She was talking about A Sword Among Lions by Paula Giddings, which was interesting, because it is a biography of Ida B. Wells, and every time I would ask [Morrison] a question about herself, she would say, “I'm not interested in myself.”

After spending over a decade on this book, do you have a strong sense now of what Toni Morrison thought made good writing?

I kept asking her that question, and she said, “Well, obviously if it’s nonfiction, the argument has to be sound and it has to be compelling, and it has to make the case for the reader in a way that nobody else has made it before.” If she was editing on a topic that she didn’t know as much about, she was literally reading everything about the current conversation to make sure [the author was] moving this argument in a different direction. Editors don't have to do that.

For the fiction…I think she was more drawn to experimental writers than to straight beginning, middle, and end writers. She said, “With Gayl Jones, I had to ask questions about characters: What is motivating this character?” With Bambara, she said, “I just needed to make sure that she didn't leave the reader behind, because she’s moving so fast.” I kept thinking, There has to be this kind of crystallized way of saying [what good writing is]. But it was the interrogation. I think that was her distinguishing mark—to publish what stories she wanted to be told, and to let the writer be the writer.

Moving Past the Shock of Dobbs

June 24, 2025 Salutations, Meteor readers, Today is the third anniversary of the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, which overturned nearly 50 years of federal protection for abortion rights. I wish I could say I never thought we’d see the day, but as a member of the post-Y2K, post-9/11, post-’08 recession, post-COVID, post-Roe generation, there isn’t a crisis I haven’t lived through. Honestly, just waiting for the rivers to turn to blood…oh wait. In today’s newsletter, we look at our disturbing new normal and try to move past our post-Dobbs shock. At least we have each other, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONTime has truly flown since 2022, when so many of us spent the day wondering, what do we do now? In the time since we’ve marched, donated, voted for abortion, made podcasts, and learned just how far people in power are willing to go to limit our bodily autonomy. So, how does the reality of a post-Roe America differ from what we once predicted? Let’s take a look:

Grey’s Anatomy can’t hold a candle to the high-stakes medical drama of the last three years. But, as in any good series, there have been some small wins. While abortion rights of patients in red states have been gravely curtailed, protections have actually gotten stronger in many blue states, thanks to laws codifying the right to abortion in state constitutions. And across the country, clear majorities have voted to protect reproductive rights, even in red states like Kansas and Kentucky. This political backlash has pleasantly surprised experts like Jennifer Klein, a professor at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs and the former director of the White House Gender Policy Council, who joined us on IG Live today, and said she was heartened to see that “abortion absolutely matters to voters.” “The level of resilience and ability to organize and fight back” has been surprising, she added, but it also “gives me hope.” AND:

COMPOSITE IMAGE OF THE TRIFID AND LAGOON NEBULAE FORMING A SICK PINK CLOUD NEAR THE CONSTELLATION SAGITTARIUS. (SCREENSHOT VIA YOUTUBE)  What Comes After Shock?Maybe something better—something steelierBY CINDI LEIVE  PROTESTORS ON LAST YEAR'S DOBBS ANNIVERSARY. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) You’ve read from my colleagues Nona and Shannon, above, about the realities of life three years after Dobbs. So one more question: How are we feeling? Three years ago today, with the devastatingly blunt sentence “Roe and Casey are overruled,” Justice Samuel Alito shattered any illusion that women in this country are, at least on paper, seen as full human beings. Reading those words wasn’t surprising—a draft of the decision had been leaked seven weeks earlier and, y’know, there were far earlier signs—but it was shocking, the way losing a loved one comes as a shock no matter how sick you knew they’d been. The shocks came rapid-fire after that: When my colleagues and I spoke to a woman who was being driven into debt after being forced to continue a debilitating pregnancy—shocking. When Kaitlyn Joshua told her story of being ping-ponged, bleeding, from one Louisiana hospital to another, none willing to treat her—shocking. When a young mom in Alabama confided that she’d been passed a stickie note telling her to travel 580 miles for care—shocking. When Jessica Valenti reported that South Carolina had proposed the death penalty for abortion patients—shocking! But, as grotesque as it is to admit, I am no longer shocked, and you might not be either. The harrowing recent case of Adriana Smith, the Georgia woman declared brain-dead but kept alive by medical staff because she was pregnant, is the stuff of horror movies, and the kind of case that at a different time and under a different president would have dominated headlines for weeks. But it seemed to me it received only modest coverage—partly because we are now living in a multiplex of horror movies (from ICE to anti-LGBTQ attacks), and partly because, after 36 long months, the shock has just worn off. This is where we are. So what happens next? On one level, of course, we have to try to retain our capacity to be shocked—to remind each other that using humans as incubators (or seizing people from their workplaces) is the kind of cruelty that may be the norm but will never be normal. I’m grateful to journalists and advocates (from Valenti to the reporters at ProPublica to legislators like Rep. Jasmine Crockett) who use their voices, data and rage to startle us day after day. But maybe there’s something more effective than shock. After all, medically speaking, when you’re “in shock,” you’re confused, weakened, not playing with a full cognitive deck—and that is the last place we want to be right now. The people I admire in this fight are using their steely resolve, legal brilliance, vast compassion, medical genius and joy every day. They have long abandoned shock, well aware that the rollback of bodily autonomy in this country is part of a well-documented global autocratic playbook in countries like Hungary, Turkey, and Venezuela. They don’t need us to be stunned. They need us to be alert, and committed, and creative—and together. What are you feeling on this anniversary? Write us at hello@wearethemeteor and let us know.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

It's Been Juneteenth All Year Long

June 18, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, Tomorrow is Juneteenth, so our offices (and maybe yours) are closed. But we couldn’t shut down our laptops without leaving you with a little bit of relevant reading and listening. Today Rebecca Carroll walks us through a year that, in spite of it all, has been culturally Black as fuck. Afterward, if you feel like luxuriating a little longer, read six incredible women on what they believe is the true meaning of Juneteenth. And of course, it wouldn’t be a celebration without hearing from Opal Lee, the “grandmother of Juneteenth,” who spoke with Brittany Packnett Cunningham a few years back about her relentless work to make this holiday a reality. Our thoughts are with Ms. Opal this week as news recently broke that she will not be leading the annual Walk for Freedom in Fort Worth, Texas, due to health complications. Remembering it’s a we thing, Shannon Melero  The Black Cultural Abundance of JuneteenthThis year, for me, Juneteenth started on February 9.BY REBECCA CARROLL  STILL THINKING ABOUT HIM (VIA GETTY IMAGES) I’ve watched it four times. Every time it’s given me something different. But what it has given me overall—in its multi-layered, legacy-laden, undeniably art-centric symbolism—is the assurance that one thing Black folks are always gonna do is find our freedom reflected in each other. I’m talking about Kendrick Lamar’s halftime show at Super Bowl LIX. It became the most-watched halftime show in history, drawing in more than 133 million viewers, and it felt not only like a call to action—because “sometimes you gotta pop out and show”—but also the very best of what Juneteenth invokes for me. Black folks’ relationship with America is obviously fraught. The country was built on our backs. Slavery is as foundationally American as the Super Bowl. And Juneteenth is, ostensibly, about American freedom. But even after the Emancipation Proclamation, Black Americans were still widely not considered to be free civilians, and that is why we continue to seek that freedom out in and for each other. After tennis star Coco Gauff won the 2025 French Open earlier this month, she said, “Some people might feel some type of way about being patriotic, but I’m definitely patriotic and proud to be American. I’m proud to represent the Americans that look like me.” And that was also the beauty of Lamar’s show—he could have easily declined to perform at such a mainstream Americana spectacle. Instead, he used it as an opportunity to reconfigure the American flag through the formation of his all-Black backup dancers, who wore red, white, and blue. Recently, when a young Black woman asked me how I write for my specific audience of readers, I said, “The same way Kendrick Lamar just performed the Blackest-blackety-black halftime show performance at the Super Bowl, for his specific audience of viewers, Black folks.” Because we know how to find each other, and speak to the insides of one another. It’s in the tradition of call-and-response, of ancestral homage, dignity, and legacy. It’s in our DNA. And it is an aegis of Black cultural jubilation in a year of targeted demoralization—when Black historic landmarks, Black museums, Black books and course curricula, and DEI initiatives are being defunded, denigrated, and dismantled.  GAUFF WITH THE ROLAND GARROS TROPHY WHICH SHE LATER AND HILARIOUSLY REVEALED IS NOT THE TROPHY CHAMPIONS GET TO TAKE HOME. (VIA GETTY) In the months after Lamar made the call, those responses have kept coming. Next came Ryan Coogler’s supernatural horror movie, “Sinners,” which both killed at the box office and earned glorious reviews. Like the Super Bowl show, “Sinners”—which follows twin bootlegging brothers who return to their Mississippi hometown to open a juke joint—is kaleidoscopic and heady, containing layers upon layers of historical references and truths. Amid recent indignities, Coogler managed to give us something rapturous, restorative, and unwavering in its tribute to Black freedom, Black love, and Black ingenuity. And then came Beyoncé’s “Cowboy Carter and the Rodeo Chitlin’ Circuit Tour,” an all-stadium concert tour celebrating her Cowboy Carter album, which explores the Black roots of country music (another quintessentially American institution). Yes, Beyoncé is an extraordinarily talented and iconic artist. But what has stood out the most to me about the Cowboy Carter tour is not Beyoncé herself but the way her daughter Blue Ivy, with every bit of her badass, 13-year-old self, has showed out to perform with her mother onstage, giving a kind of “fuck-you”-fueled intensity well beyond her years. To me, Blue Ivy represents the collective power and tenacity of Blackness, and I imagine is exactly what the ancestors had in mind when they thought, We gonna call it Juneteenth, and then we gonna do whatever the hell we want to on this day forward from heretofore.  CAN WE GET A YEE-HAW? (VIA GETTY IMAGES) And then there was The Met Gala. While I have real criticisms about the event as the standard of what constitutes haute fashion, and about its curated exclusivity (read: whiteness), I couldn’t help but feel like this year’s theme, “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style,” was another response to Lamar’s call. Inspired in part by Black scholar Monica L. Miller’s book, Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Style of Black Diasporic Identity, all our fave fancy Black folks walked that blue carpet wearing the fiercest looks, channeling the very essence of Black elegance, just like the one that Black folks have historically created for Juneteenth celebrations.  SO...ABOUT THAT ALBUM? (VIA GETTY IMAGES) After that, the ancestors came through…again: It was as if Annie, the Hoodoo healer from “Sinners,” gathered together a very particular recipe of roots and herbs to help conjure up some very large flames on a very specific plot of Southern land. It’s not nice to say, but when the largest surviving plantation mansion in the South burned to the ground on May 15, my first thought was, “Well, you shouldn’t have been enslaving people.” The demise of Nottoway Plantation in White Castle, Louisiana—which, like many plantations, had become a popular wedding venue—was reportedly caused by an electrical fire. Whatever the case, for it to happen during this run of Black cultural ascension seemed like poetic justice, and needless to say, the Black memes were delicious. There are many more examples—Amy Sherald, Lorna Simpson, Rashid Johnson, and Jack Whitton all having solo art shows this year; Audra McDonald being a classy boss bitch, and giving an utterly singular “Gypsy” performance at the Tonys; Rihanna continuing to populate so glamorously—but given where we are in this moment, it feels right to end with Doechii’s speech at the BET Awards last week. Because ultimately, Black freedom has always meant getting other people free, too. Doechii, who won the award for Best Female Hip-Hop Artist, chose to use her platform during the live broadcast to speak out against the ICE immigration raids happening in Los Angeles. “These are ruthless attacks that are creating fear and chaos in our communities in the name of law and order,” she said. “I feel it’s my responsibility as an artist to use this moment to speak up for all oppressed people: for Black people, for Latino people, for trans people, for the people in Gaza.” Juneteenth, which became a federal holiday in 2021, is about Black freedom. But it’s also about the function of freedom itself.

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()