Voices From Inside Iran's Freedom Movement

NEWS

Mahsa Amini's death was only the beginning

By Gelareh Kiazand

Today marks exactly a year since the death of Mahsa “Jina” Amini, a young Kurdish woman who had been detained by what’s known in Iran as the Morality Police for “improperly” wearing her hijab, and who went into a coma while in custody and died shortly after. Despite the government’s attempts to cover up the circumstances of Amini’s arrest, pictures of her in the hospital and the eventual news of her death sparked massive protests and set the Woman, Life, Freedom movement in motion, the scale of which took many by surprise. Tens of thousands of people spilled into the streets in around 100 cities, in an explosion of suppressed pain over years of censorship, patriarchy and government coverups.

The government harshly retaliated: It’s estimated that in the first six months of the protests, more than 500 police and protesters were killed, 20,000 people arrested—and at least six executed. Internet access was disrupted in an attempt to suppress the protests.

The brutality and murders did scare some people off the streets. By January, many acts of defiance had migrated to social media, where high school girls were dancing, removing their headcovers, and pulling down the pictures of government officials, including the supreme leader Ayatollah Khamenei. Soon, people began reporting cases of school poisonings that ultimately affected more than 1,000 girls, most suffering from breathing problems. Even though the government arrested those who carried out the so-called “nitrogen” gas poisonings, many parents suspect authorities were involved, or at the very least looked the other way.

In April, the streets of Tehran were again filled—this time with women not wearing any form of hijab, in violation of national law. The government started issuing economic fines to celebrities, business, and ordinary citizens. Small cafes with customers who refused to cover became prime targets of police harassment and closures. Around 150 businesses were shut down.

As the anniversary of the protests approached this summer, authorities are still arresting, intimidating, and threatening protesters and their families. Niloufar Hamedi and Elahe Mohammadi, the two women journalists who first reported on Amini’s death, are still under arrest and awaiting trial with charges of espionage. Seventeen more journalists remain detained.

Whatever comes next may make history. The government has taken no steps to address the movement’s cries of injustice, and President Ebrahim Raisi, who won in a highly engineered election with the lowest turnout on record, hasn’t improved Iran’s struggling economy. But voices seeking to topple the regime, both on the ground and online, have only grown louder.

Women have always been a political force in Iran. We spoke with several of these women (and one man), all of whom have been profoundly affected by the past year’s uprising. All of them have been given pseudonyms to protect their identities.

Pardis, 24, runs her family’s small cafe in Tehran. During the peak of the uprising, she sheltered injured and runaway protesters. The authorities ordered her to refuse the protesters or be arrested. She chose the latter, and was taken to prison for 24 days.

“If anyone can change this situation, it is the people of Iran. Look, I was not a political person at all; I was thinking about parties and boys and these things. I went to prison because of my beliefs—it’s ridiculous to be afraid now. They are forcing us to show a reaction to the killing of Mahsa Amini, which was not even justified. Why should teenagers be killed? I was living my life, but after these events, how can we remain silent? [The movement] has changed everything, in my opinion. Even the most distant people, the most religious people, whether they like it or not, are affected by this revolution.”

Ameneh is a 28-year-old woman from Zahedan, Baluchistan, a conservative and underserved province that was one of the country’s most active areas during the uprising. Her family prohibited her from continuing her studies at a young age, and never let her venture far from her home city. The uprising was the first time her family allowed her true independence.

“Here, the conditions are again like those first weeks. The city is very controlled. People’s phones are checked. They are very sensitive to the anniversary and scare the people so they don’t come out. People have no right to participate in the rally and the mosque.

“From the first day, [prominent Sunni spiritual leader] Molavi Abdul Hamid criticized the killing of Mahsa Amini. The people of Zahedan are very fond of Molavi and they also supported him. [As a result] Friday prayers were and still are strictly controlled, and they even put checkpoints in the city a day or two before. My brother was arrested by intelligence forces in mid-November [for being] a member of mosque security and the liaison to deliver medicine to the injured people of Zahedan’s Bloody Friday. Later they attacked our house many times and searched and took all my brother’s belongings. At that time, one of our acquaintances said that these drugs should be brought from Tehran, but it was very risky. Finally, I decided to go to Tehran and bring these medicines.

“[Growing up] I really wanted to study or dress the way I like, but it was impossible. At that time, when I said I wanted to do this, I was alone, there was no one to support me, there was no other girl like me. But now I don’t feel alone anymore and I have more courage. I see this change in both women and men.”

Soha is a 17-year-old student who is religious and attended the protests with a headscarf. For her, the movement was about standing for the freedom of women, who should not be defined by hijab. Her mother, Mitra, 54, who also is religious, joined her in the protests.

Soha: “I have never been insulted by people who don’t believe in hijab. But I have seen many times that girls who don’t wear a headscarf are insulted or made to feel insecure by the morality police or by women who are hired by the Islamic Republic to intervene in the issue of hijab.”

Mitra: “As a Muslim woman, I cannot allow them to kill people under the pretext of my religious beliefs. In my opinion, the Islamic Republic is not only not Muslim, but [also] fueling anti-Islamism. In the religion of Islam, it is not said to keep people hungry and to keep the hijab. Islam does not say kill or imprison anyone who disagrees with you. Hijab is important in Islam, but not as important as a person’s life. Was there a problem with [Amini’s] hijab from the point of view of Islam?”

Soha: “The new wave of the movement will start soon, and in my opinion, religious people will play a big role in this new wave.”

Mehdi, 19, is a student in Tehran. At the rallies, he witnessed his friend getting shot, and he himself was beaten by the security forces. He and his friends believe the forced ruling of “old men” needs to end.

“In 2009, I was very young, but I understood that people were protesting and I saw that they were being suppressed. At that time, my family was not against the Islamic Republic and my father even worked in the Revolutionary Guards, but he had seen things up close that had an impact on him, and since then, his perspective changed. So he resigned from his job. Many people who thought that the Islamic Republic had no problems realized that they were on the side of corruption. People see that this government is only lying to them and this is no longer acceptable to many. My father always said that if anyone can oppose the [clerics in the Islamic republic], it is women.

“People want stability. They want a good economic situation. A few nights ago, one of my friends told me to go to the embassy for immigration. I said that the future is here; we just have to build it.”

Rana, 35, is a teacher from Kurdistan, the province where Amini is from. Kurdistan, like Baluchestan, faced some of the harshest crackdowns. Doctors were working secretly in people’s basements to help the wounded. Many homes were open to neighbors so the community would not be weakened.

“In Kurdistan, I feel the meaning of women is different than in the rest of the country. They are raised as fighters, live as fighters, and die as fighters. Because we as Kurds have always fought for our ethnicity, this seems to have been born within the women. The slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom” [signifies] a freedom of humanity which shouldn’t be defined by what is worn or not worn. It is the freedom…of choosing who I am, bearing its responsibilities, and shaping my life through that. I feel the women of Iran are finally starting to understand what freedom can hold.”

Gelareh Kiazand is a Canadian-Iranian based between NYC and Toronto who has worked in Iran’s film and documentary industry for 12 years as well as covering stories in Afghanistan and Turkey. In 2016, she became Iran’s first female DoP for a fiction feature film, post-’79 revolution.

The Global Public Health Crisis We're Ignoring

NEWS

It’s gender-based violence—a slow, consistent, menacing reality in the lives of women, girls and gender-nonconforming people worldwide that’s been quietly getting worse, not better.

BY ANNA LEKAS MILLER

In 2015, world leaders convened at the United Nations to announce the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. Target 5.2 was one of the most thrillingly ambitious: to eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private sphere by the year 2030.

Halfway to 2030, though, not only are we far from that goal—we’re regressing.

Every day in Mexico, at least ten women are killed—a rate that has more than doubled since 2015. In Iran, intimate partner violence rose 20% during the pandemic’s first few months; in Spain, 23%. And in the United States, femicide—the killing of a woman because she is a woman—has increased by almost 25% since 2014. These aren’t isolated examples; recent surveys indicate that gender-based violence (GBV)—a public health crisis that encompasses femicide, female genital mutilation, rape, online abuse, harassment, and more—is on the rise globally.

“There’s never been a more urgent time to address gender-based violence, and I’ve been doing this work for decades,” says Rosa Bransky, CEO of Purposeful, a Sierra Leone-based organization that works with women and girls across Africa. “Globally, most of the advances of the past 20 years have been rolled back, and we’re seeing both a rise of profound violence against women and a rise in women-led activism against it.”

The data points are everywhere. Pick up your phone in late summer 2023, and you might see documentation of GBV in Italy, where the gang rapes of two young girls seized the country’s attention; in Bosnia, where a man killed his ex-partner on Instagram Live; or even on a remote ice sheet in Antarctica, where women scientists report that harassment and assault are so commonplace that they work with hammers tucked into their uniforms to stay safe.

Like many epidemics, this one seems borderless, especially in our tech-fueled world. “Yet unlike any other epidemic, we’re failing to properly research it or even take it seriously,” says Leila Milani, program director at Futures Without Violence, a United States-based nonprofit. “When was the last time you heard a political candidate talk about it as a top issue? You don’t—because it’s not considered to be one.”

UNDERSTANDING THE UPTICK: FROM PANDEMICS TO “PATRIARCHAL AUTHORITARIANISM”

First, let’s be clear: even when politicians don’t always see this as an issue, the public certainly does. The last decade has brought wave after wave of powerful protests led by survivors and their allies. In South Africa, there was 2018’s Total Shutdown movement, in which women took to the streets to protest the government’s failure to deal with steep femicide rates. In Argentina, Ni Una Menos (“Not one less”) started as a massive 2015 protest after the murder of a 14-year-old pregnant girl by her boyfriend; it ultimately helped usher in major political victories on abortion and other issues across South America. In 2017, the viral #MeToo campaign became a global movement demanding accountability from perpetrators.

But while survivors’ voices still ring loud, rates continue to rise.

The reasons are complex. COVID, of course, took a toll; domestic violence rates increased by 25 to 33 percent globally, and girls left school in greater numbers, elevating their odds of child marriage and intimate partner violence.

Other global trends play a role as well. The world is facing the highest number of violent conflicts since the Second World War, in places from Ukraine to Ethiopia—and women in conflict zones are more than twice as likely to be brutalized by an intimate partner. Add to this the fact that climate change, which disproportionately impacts the world’s poorest and most vulnerable, also puts women at increased risk of violence—and Indigenous land defenders are frequently threatened with sexual violence while rarely being protected by the state.

“If you’re a woman, non-binary or trans person, you’re facing a level of risk in any context,” says Celia Turner, partnerships management officer at Urgent Action Fund, a global consortium of regional feminist funds. “So in conflict zones, of course this risk escalates. We’re also seeing that conflict is tied with climate change, so gender-based violence is often at the intersection of overlapping crises.”

The effects of climate change particularly impact Indigenous women and farming communities, who are accustomed to living off of the land. Additionally, Indigenous land defenders are frequently threatened with sexual violence, and are rarely protected by the state.

“Often, gender-based violence is seen as a private issue, but it is a highly political issue,” says Rosa Bransky, the CEO of Purposeful. “It is connected to the climate crisis and the rise of authoritarianism—just as the world is burning, so are women’s bodies.”

Undergirding all these trends is our current era of what scholars call “patriarchal authoritarianism,” in which strongmen leaders in dozens of countries have launched simultaneous assaults on women’s rights and on democracy. In the U.S., the implications have been immediate: the overturn of Roe v. Wade in 2022 triggered a doubled rate of reproductive coercion—in which an abuser sabotages a partner’s contraception, intercepts birth control, or otherwise hinders their ability to control their own fertility.

“We are confronting a global anti-rights movement that wants to set back any progress on gender equality,” says Monica Aleman, international program director for Gender, Racial and Ethnic Justice at the Ford Foundation. “And they must be stopped.”

WHO GETS HURT: “THERE ARE A LOT OF STEREOTYPES”

In order for it to be stopped, Aleman notes, we must first recognize that violence doesn’t affect everyone equally. Women of color and other communities with overlapping marginalized identities—for instance, gender-nonconforming people, or those with disabilities—experience the epidemic of violence disproportionately. “When we talk about gender-based violence, there are a lot of stereotypes and you think of ‘cis man physically attacks cis woman,’” says Paige Andrew, a Trinidad and Tobago-based co-manager for FRIDA Young Feminist Fund. “But we need to address how violence shows up for people with diverse gender expressions.”

And it shows up more viciously: While nearly one out of every three women experiences physical or sexual violence in their lifetime—a number advocates agree is a vast understatement—almost half of trans women and nonbinary people do. (In the U.S., Black transgender women are especially vulnerable; they comprise 66 percent of all trans murders.)

GBV also cuts along socioeconomic lines. “It is particularly bad in rural areas, where there are fewer resources for abused women,” says Kristen Rand, government affairs director at the Violence Policy Center. Their 2022 report found that Native women in Alaska and Black women in the Deep South—historically the most economically marginalized groups—experience the highest rates of femicide in the United States. “Along with a lack of resources for women, there is easy access to guns and no mechanisms in place to make sure that abusers have their firearms removed,” Rand explains.

Still, these stories rarely make the front pages of our newspapers—and when they do, they are often treated as “true crime” tales, says Rand. “We are constantly frustrated with how the media covers [domestic violence] as just an incident,”—rather than as a systemic public crisis that might actually have solutions.

SO: WHAT ARE THE SOLUTIONS?

Patriarchal defenses of GBV lie deep in our society—the idea that men brutalizing women is central to their gender roles, or an evolutionary fact. “The inevitability of violence—and the way that girls are taught that [it] is part of life—is one of the most violent things about violence,” says Bransky.

That said, she and other advocates do have hope—mainly because they are watching young activists pioneer bold solutions to GBV around the world. In Sierra Leone, where Purposeful works, Bransky points to a group of girls living in the rural north who used grant money to set up a reporting protocol for instances of rape and sexual violence; activists also led the overturning of the country’s ban on pregnant girls from attending school.

And government will and political leadership are crucial here. After the Total Shutdown protests, South Africa hosted a presidential summit and created a committee to end GBV, resulting in the 2020 launch of a National Strategic Plan on Gender-Violence and Femicide. In the U.S. last May, the White House launched the United States’ first national plan to combat gender-based violence. Advocates like Milani (who was an advisor) say this was overdue, pointing out that the U.S. is the only industrialized democracy in the world that has not ratified the United Nations’ Convention to End All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), nor has it been able to pass the Equal Rights Amendment.

Another solution, of course, is funding for solutions to ending GBV—something many advocates say is shockingly low. At The National Domestic Violence Hotline, calls have hit a historic high, but “at the end of the day, domestic violence will remain an epidemic in the U.S. because it is viewed as a ‘women’s issue’ and thus is significantly under-resourced,” says Katie Ray-Jones, CEO of The Hotline.

And even when funding exists, it can also reinforce geographic and social inequities, since major funders are often based in the Global North and set the agenda about how money should be spent, says Aleman. “Even when this funding reaches the Global South, it often only reaches the capitals—and isn’t easily distributed to rural areas who need it the most,” she says. “We need to make sure we’re not reproducing the colonial model in our grantmaking.”

But still—there are those thousands of people on the streets and social media everywhere from Rome to Johannesburg, showing us that they will not stop fighting for the eradication of this epidemic. Advocates say that their passion provides a roadmap that politicians and funders should follow.

For Aleman, it’s all about having the courage to treat gender-based violence like the public health crisis it clearly is. “I want us to be more decisive in our response to the anti-rights movement here and abroad,” she says. “We need to fund the feminist movement unapologetically and without hesitation.”

Bransky agrees. The solutions are known and within reach, she says, if only we listened to the survivors themselves. “We don’t need more innovation or task forces,” notes Bransky. “The solutions exist”—and they’re being led by feminist leaders everywhere.

Anna Lekas Miller is a writer and journalist who covers stories of the ways that conflict and migration shape the lives of people around the world. She is the author of the book Love Across Borders and runs a newsletter by the same name. Follow her on Instagram: @annalekasmiller.

This is part of a new series between the Ford Foundation and The Meteor. Learn more at ourfreefuture.org.

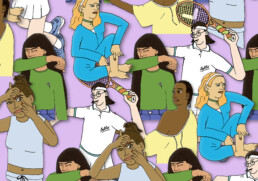

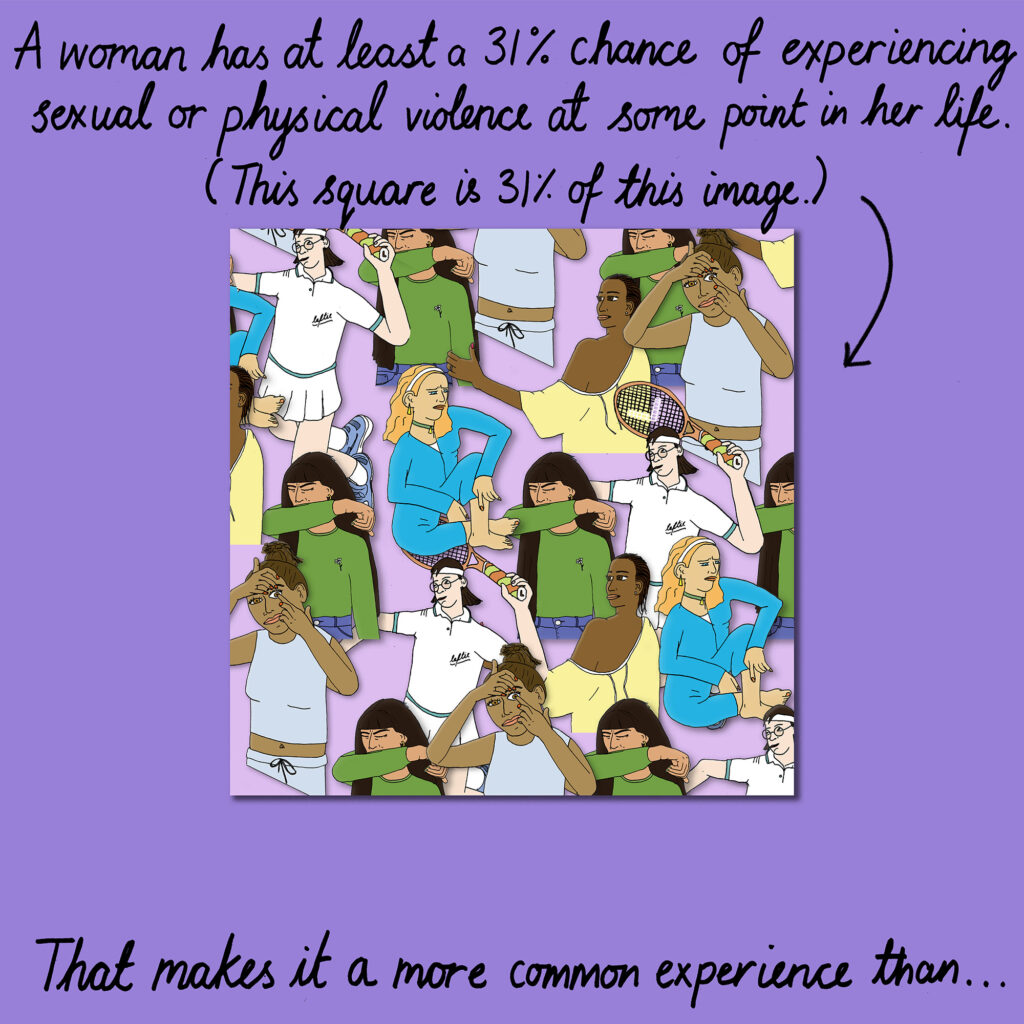

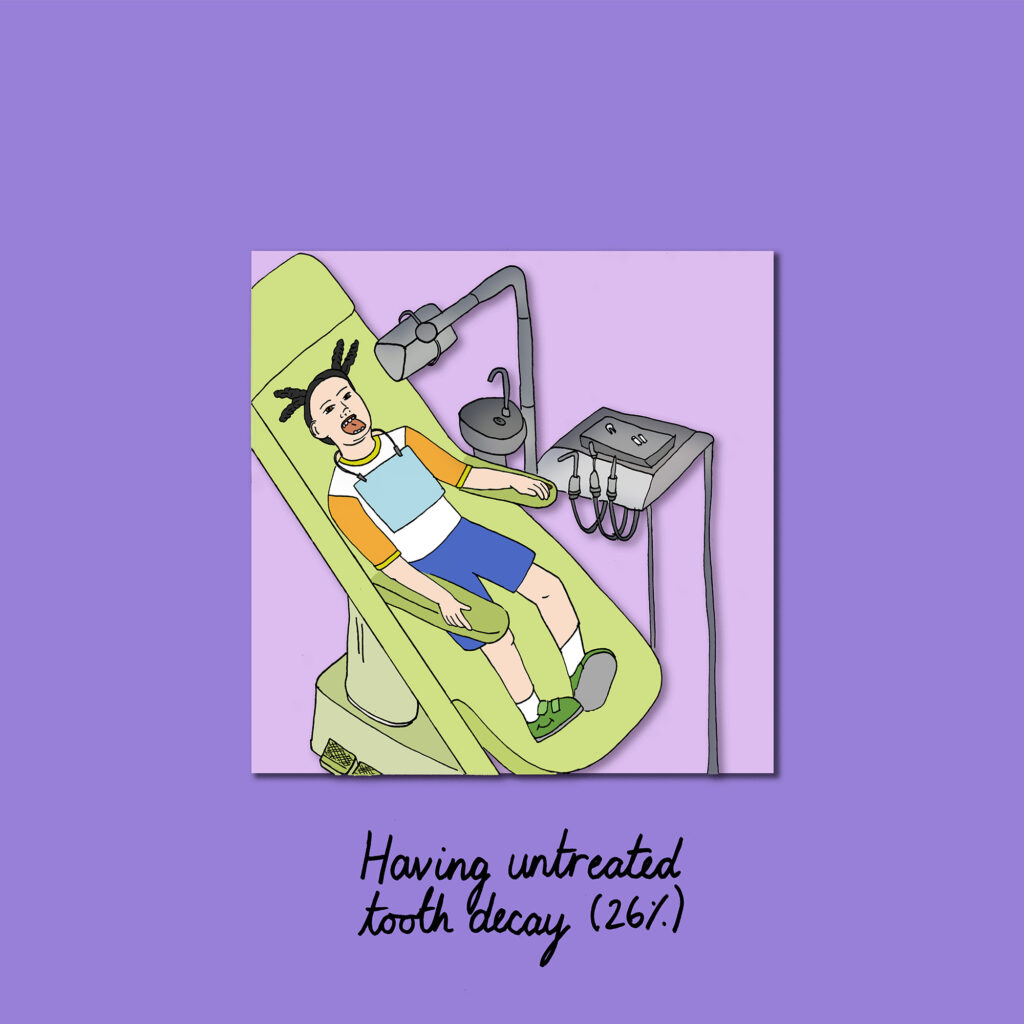

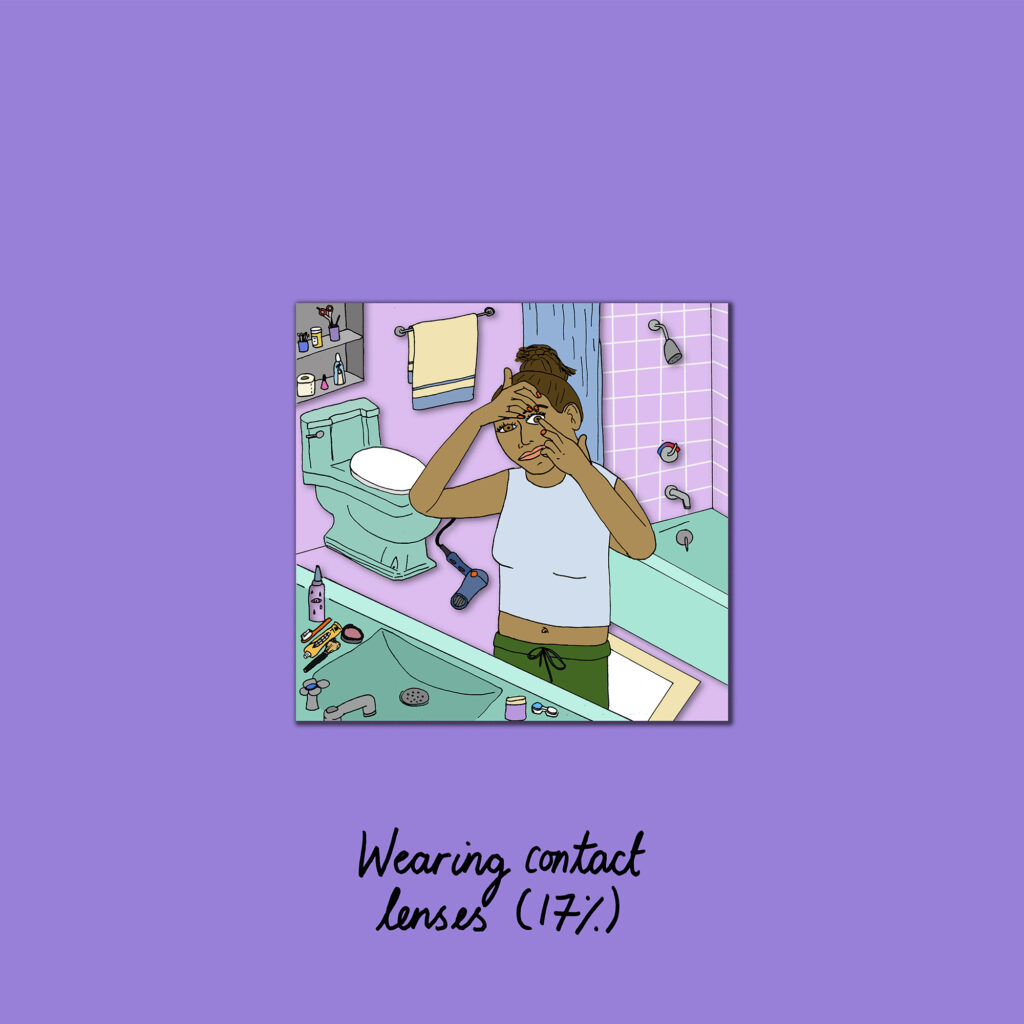

How common is gender-based violence?

NEWS

The violence that women, girls and gender-nonconforming people experience is so ubiquitous that it can take on this feeling of inevitability or mundane everydayness. But the violence we experience is shocking and it should remain so. In this series of illustrations, I use U.S. statistics about other common experiences in an effort to reawaken us to the unacceptable rate at which this violence happens around the world.

Finding a statistic to show the enormity and frequency of this violence was nearly impossible. The 31% figure, from the World Health Organization, is high—but it still vastly understates the problem because it does not count femicide, harassment or the many ways that systemic violence against women, girls and gender-nonconforming people affects their lives.

Perhaps if we see the true scale of GBV, world leaders might finally treat it like the deadly global public health crisis that it is.

This illustration is part of a new series between the Ford Foundation and The Meteor. Learn more at ourfreefuture.org.

About the artist

Mona Chalabi is an award-winning writer and illustrator. Using words, color and sound, Mona rehumanizes data to help us understand our world and the way we live in it.Her work has earned her a Pulitzer Prize, a fellowship at the British Science Association, an Emmy nomination and recognition from the Royal Statistical Society.

Sources:

- Getting a seasonal allergy: CDC.gov

- Having untreated tooth decay: CDC.gov

- Ever being bitten by a bed bug: YouGov.com

- Experiencing insomnia: CDC.gov

- Wearing contact lenses: CDC.gov

- Breaking a hip: JAMA Network

- Getting breast cancer: Cancer.org

- Getting a master’s degree: Census Bureau

- Lefthanded: Archives of Public Health

"Only Yes Means Yes"

"Only Yes Means Yes"

Cristina Fallarás on the changing tide of sexism in Spain

Last month during the Women’s World Cup medal ceremony in Sydney, Australia, the president of the Royal Spanish Football Federation, Luis Rubiales, grabbed and forcibly kissed player Jenni Hermoso on the lips in front of the world’s cameras. Hermoso filed a formal complaint amid a global outcry and a national rally against sexism in Spain. Rubiales potentially faces jail time for his crime due to a new Spanish law widening the definition of sexual assault.

Cristina Fallarás is a journalist, blogger, author of eleven books, and one of Spain’s most celebrated feminist activists. In 2018, in the wake of #MeToo, she created the hashtag #Cuentalo (Tell Your Story), which generated three million posts in just 10 days.

The Meteor’s Mariane Pearl spoke to Fallarás about the public mood in Spain, what Rubiales’ reaction reveals about sexism, and why a kiss isn’t just a kiss.

Mariane Pearl: Five days after the kiss, a defiant Rubiales spoke at a general assembly meeting of the Royal Spanish Football Federation. The audience, overwhelmingly male, began to applaud as he refused to resign. He claimed that the kiss was consensual and that Hermoso brought his body close to hers. What did you feel when you heard him speak?

Cristina Fallarás: His speech will remain in the annals of misogyny and self-entitlement. As he spoke, I became physically ill. My hands began sweating, I had vertigo, akin to this nauseous feeling you get when you walk alone at night in a dangerous place. During his speech, he pounded on the desk, screaming five times in a row that he wouldn’t resign. Rubiales wasn’t even defending himself; he was attacking Jenni Hermoso. It was a classic case of revictimization.

He also talked about “false feminism.” What do you think he meant by that?

He said this was a social assassination and that he could have given the same kiss to one of his daughters, whom he called true feminists. He claimed “false feminism” is a plague in our country. But Rubiales belongs to what I call the “boys’ club.” Members are generally white, heterosexual, older, and rich. It’s a closed circuit with a misogynistic mindset that [trumpets] virility and abhors what they call “fake” or “radical” feminism. They exchange numbers, documents, money, and women.

Still, the public reaction was huge. Even the Prime Minister of Spain, Pedro Sánchez, called for Rubiales to step down. Does the massive reaction reflect a change in Spain’s mindset about gender equality?

Rubiales’ arrogance raised a giant wave of protest in the country and worldwide, a collective “enough is enough” sentiment. This movement is a massive rebuke. [And this case is] not happening in a vacuum. Just a year ago, the government passed a law known as “Only Yes Means Yes,” which puts Spain at the vanguard of the global battle for sexual consent. It establishes sexual aggression as a crime with or without violence or intimidation.

As a result, thousands of women have come forward to denounce their perpetrators. There are 50 new shelters established by the government across the country. Our society was ready for this, but the recent rise of Vox, the far-right party, is a cause for concern. Vox programs [would] roll back decades of progress by blocking abortion access, repealing legislation on gender-based violence, and shutting down the ministry of equality and LGBTQ centers. We are vigilant, but I am terrified of what would happen should Vox win in the next elections.

Many women have reacted to the fact that what brought Rubiales down was a “simple” kiss.

The media only speaks about violence against women when there is a femicide, gang rapes, or if the victim is a minor. But the Rubiales kiss tells us that every assault matters. Laws are important, but they are useless if there aren’t visible stories—like the kiss—that are symbolic enough to start a new narrative and capture people’s indignation.

In 2018, you launched the sister of #MeToo, named #Cuentalo. Millions of women testified. And just last week, you launched a new campaign to denounce sexual violence, mostly in the workplace. Were you surprised to receive thousands of answers?

Twitter is very efficient for multiplying hashtags and giving visibility to a movement, but Instagram is different. It’s intimate. This time, people are not retweeting a hashtag; they are writing to me personally and I am answering them one by one, reposting their stories after editing them to ensure anonymity. Sometimes, when I receive a testimony, I look at the person’s account and what I see are women on the beach, pictures of kittens, mothers, and grandmothers with children. So it’s not the world of militants or even feminists; these are the women next door. This is everybody.

Big white lies

|

No images? Click here  September 20, 2023 Greetings, Meteor readers, The first week of school is just about done. Congratulations, you’ve all survived! Only an entire academic year to go.  In today’s newsletter, we examine the new(ish) way conservatives are trying to reshape history, applaud successful women, and share some weekend reads. Academically yours, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONBig white lies: Over the last few months, a particular threat has been in the air: inaccurate historical teachings. What once felt like a uniquely red-state problem has now crept its way into the curriculum of a Pennsylvania school district. According to Popular Information, the Pennridge School Board is requiring teachers to incorporate lessons from the 1776 Curriculum into their social studies classes. The simplest way I can think to explain this curriculum, developed by Hillsdale College in Michigan as a right-wing guideline for educators (and in direct response to the historically accurate 1619 Project), is slavery apologetics for kids. This new K-12 curriculum teaches students that although the founding fathers participated in slavery, not all of them actually wanted to and eventually freed their slaves. It also trots out the tired argument that the Civil War wasn’t really about slavery at all but was instead about states’ rights. (Ahem, no.) Ninth graders will be served a piping hot plate of propaganda that claims “what was unique to America was the right to vote at all” and the “rapid rate” in which the vote was given to women. (The latter is demonstrably false.) The 1776 Curriculum is just the latest far-right attempt to rewrite history—and cater to the relatively small but loud voices reinvigorating American exceptionalism. It’s become so pervasive that Florida’s public university system is about to approve a heavily Westernized Christian alternative to the SATs called the Classic Learning Test. Previously only used as an admission test for private Christian colleges, the CLT promotes a “classical” curriculum and will be an option for students applying to public universities across the state. What’s clever about the CLT is that its inherent racism is not immediately obvious. The reading comprehension portion of the exam focuses on writings by figures like Martin Luther and Thomas Aquinas. It also places “an emphasis on Greek, Roman, and early Christian thought.” That’s fine if you’re trying to get into seminary school, but a “classical” education isn’t exactly a marker of a student’s readiness to enroll in Florida State. Not to mention that the test legitimizes a style of teaching that cuts out the works of women and writers of color. This move toward a revisionist, borderline-white-power version of history would be laughable if it weren’t all so insidious. Even before modern white supremacists and Moms for Liberty started infiltrating school boards, most American history classes were struggling to provide the full picture to students. It’s bad enough that most Millennials got a gentle, glossed-over version of world events like Columbus “discovering” America (i.e. committing genocide), but now basic, long-held facts are up for debate. AND:

JUST CLICK THE LINK ABOVE TO GET YOUR UNIQUE SHARE CODE TO SEND TO FRIENDS. IF FIVE OF THEM SIGN UP, WE'LL SEND YOU A METEOR TOTE! ALREADY HAVE A CODE BUT CAN'T FIND IT? NO WORRIES, IT'S WAITING FOR YOU DOWN BELOW. ⬇️

WEEKEND READS 📚On fútbol: Spanish soccer has been holding our attention for the last few weeks. But the women of La Roja have been fighting an uphill battle for years. (The Athletic) On the optimal self: Fitness and sleep tracking can be great. Until your tracker starts gaslighting you. (Slate) On trial: Google. (The New York Times)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their unique share code or snag your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Let Us "Girl Walk" In Peace

|

No images? Click here  August 24, 2023 Hey there, Meteor readers, I was mindlessly scrolling through Instagram the other night and I came across a Story from Peloton instructor Cody Rigsby, in which he described having the Sunday scaries but for the end of summer. So now, of course, I’m having summer scaries. Summer is almost over? That means the year’s almost over. Literally, where did 2023 even go?  In today’s newsletter we attempt to take the clown car of Republican candidates running for president seriously, consider “girl trends,” and share some reading for your weekend. Already wearing a sweater, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONJust girl things: It seems like everywhere you turn, normal everyday activities that women do are now “girl” trends with a bevy of accompanying think pieces: Girl dinner. Girl math. Strawberry girl. That girl. Soft girl. Tomato girl summer. Hot girl walks. Lazy girl jobs. The reaction to the girlification of women’s lives has been largely negative. The trend has been called infantilizing and toxic, particularly the idea of “girl dinner,” which shows women eating snacks like popcorn and calling it dinner. Are these videos reinforcing eating disorders or is it reflective of the varied ways in which American women approach food and mealtimes? Is it both? Is it neither? But let’s think about this for a sec. Is it being called a girl that’s supposed to be so offensive? It wasn’t offensive when Beyoncé told us that girls run the world. In what context are we okay with “girl”? Does the hot girl walk I take every day to clear my head betray my allegiance to intersectional feminism? Here’s my two cents on it (which, in girl math, is worth about 100 USD): The act of turning adult behaviors into cutesy girl trends may just be a new way in which young women are using social media to communicate longstanding gender disparities to their peers. What is a girl dinner if not commentary on food insecurity? What is girl math if not highlighting how women uphold the economy despite inflation and the gender pay disparity? What are lazy girl jobs if not a referendum on the idea that we should be working all the time? What are Strawberry/Soft/Tomato girls if not eviscerating the unnatural standards women are expected to adhere to when they present themselves to the world? So maybe the question shouldn’t be “does girl math make sense” and should instead be why do women have to figure out such creative ways to explain how cost, worth, and value are all completely different concepts? Maybe the “girls” are just too smart for everyone.  LOLsob: Your evening hours are limited and your mental health is precious, so we’ll understand if you opted out of watching the first debate of the 2024 presidential race last night and mostly enjoyed the memes about Chris Christie today. But since each of the eight Republican candidates on display (Trump, awaiting arrest, wasn’t there) represents a vision of America that is one election cycle away from becoming our next reality, it’s worth considering who they are. A majority of these candidates, including front-runner (behind Trump) Ron DeSantis, don’t believe in climate change. Mike Pence and Tim Scott want to institute national abortion bans after 15 weeks of gestation. The whole lot of them want to revive the failed war on drugs and use the military to suppress the import of fentanyl and slow immigration. And while some of that seems absolutely absurd, it also seemed absurd that the guy from The Apprentice could be president…and look what happened there. While Nikki Haley was voted Closest to An Adult in the Room by debate analysts last night, we all know that Ron DeSantis has the most potential to snatch this nomination out of Donald Trump’s hands. If you live in a blue state, perhaps you are checked out. But the fact of the matter is, he’s coming into this election with the might of Florida behind him, the support of powerful mom groups, and his youthful appearance. (That last one shouldn’t matter, but, alas, it does.) Sadly—and I literally hate to say this—we can’t afford to discount DeSantis or the other contenders; even if they don’t win, chances are high they’ll land somewhere in the cabinet should a Republican win the presidency. And the road to an election day isn’t as clear cut as Democrats might hope it is. AND:

JUST CLICK THE LINK ABOVE TO GET YOUR UNIQUE SHARE CODE TO SEND TO FRIENDS. IF FIVE OF THEM SIGN UP, WE'LL SEND YOU A METEOR TOTE! ALREADY HAVE A CODE BUT CAN'T FIND IT? NO WORRIES, IT'S WAITING FOR YOU DOWN BELOW.

WEEKEND READS 📚On Afghanistan: Two years after Yalda Royan fled Afghanistan, she examines why so many refugees are still trapped in “legal limbo.” (Slate) On shopping IRL: The experience of actually going to a store is becoming an artifact of the past. But why? (Vox) On rush week: Unpacking the inherent whiteness of the internet phenomenon Bama Rush. (The New York Times)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their unique share code or snag your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Gold Medals and Sexual Harassment

|

Evening, Meteor readers, It was a wise philosopher (Aaliyah) who once said, “If at first you don’t succeed, dust yourself off and try again”—and that’s apparently the advice Joe Biden is following with his new SAVE program, which aims to limit interest-rate accrual on student loans and improve some existing repayment plans. I’ll give him an A for effort and an I for execution. What’s the I stand for, you ask? *I* am not paying back these loans in this lifetime.  In today’s newsletter we dig into the full story on The Kiss during the Women’s World Cup trophy ceremony, a change to abortion restrictions in Texas, and a little bit of good news. Consensual xoxo, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON“It started out with a kiss, how did it end up like this”: On Sunday afternoon, Luis Rubiales, president of the Royal Spanish Football Federation (REFF) had the honor of handing out gold medals to Spain’s women’s national team after their World Cup win over England. But what should have been a proud and beautiful moment for all the women of La Roja (the team’s nickname) turned into an international debacle when Rubiales grabbed team captain Jennifer Hermoso by the back of her neck and kissed her on the mouth. He then proceeded to smack her on the bottom—all while cameras rolled. As if that wasn’t enough, Rubiales later entered the women’s locker room and joked to the team that they were all invited to his wedding with Hermoso. In a social media video, Hermoso said of the moment, “¿Qué hago yo? Mírame…No me ha gustado.” What do I do? Look at me…I didn’t like it. After the moment became an international story, though, Hermoso downplayed the incident, saying, “It was a natural gesture of affection and gratitude.” But it wasn’t just a gesture. Not only did it read like sexual harassment in real time, the “kiss” is also symptomatic of much deeper issues which have been plaguing La Roja and the REFF for years. JENNIFER HERMOSO DOING THE ONLY KIND OF KISSING WE WANT TO SEE AT A MEDAL CEREMONY. (IMAGE BY ALEX PANTLING VIA GETTY IMAGES) In the lead up to the World Cup, 15 of the best players in Spain who had mostly been expected to play on the national team withdrew themselves from consideration in protest of the way the REFF, led by Rubiales, and coach Jorge Vidal had been treating them. The players—who became known in Spain as Las 15—sent an email accusing Vidal of creating an oppressive work environment and highlighting the ways in which the REFF had provided subpar training facilities which they believed had led to injury. (A familiar accusation, also present in the 2020 lawsuit between the USWNT and the US Soccer Federation.) For their part, Las 15 wanted to resolve the issues internally. But in an effort to control the narrative, Rubiales went public with the email and, according to some players, willfully misconstrued what was written in an effort to paint Las 15 as merely disgruntled athletes. All of this behind-the-scenes tension is what makes The Kiss more than just an act of celebration gone wrong. Rubiales holds the fate of Hermoso’s career in his hands. If she wants to continue being a part of the national team, not only does she need to perform at an elite level, she needs, as a huge sports star in Spain, to be a peacemaker between the REFF and the players. After two days of pressure from fans and Spain’s minister of culture and sport, Rubiales issued a halfpology in which he acknowledged the kiss as a “mistake” and then followed it up with, “Here we saw it as something natural and normal. But on the outside it has caused a stir, because people have felt hurt by it, so I have to apologize; there's no alternative.” He basically hit the world with a “sorry you feel that way” and kept moving. This World Cup win is Spain’s first and it’s the kind of accolade the players desperately need to further fuel their fight for equal treatment. It took the US Women’s National Team toiling for 20 years for their federation to start listening to them and they didn’t even see the fruits of that labor until their fourth World Cup win. Here’s hoping we see a faster turnaround for Spain—and all the other women’s teams around the world battling for respect. AND:

HAVEN'T SIGNED UP FOR OUR AMBASSADOR PROGRAM? JUST CLICK THE LINK ABOVE TO GET YOUR UNIQUE SHARE CODE AND START EARNING POINTS TOWARD MERCH!  TELL ME SOMETHIN' GOODHappy news exists! Today’s proof:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their unique share code or snag your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

A Livestreamed Femicide in Bosnia

|

Hey there, Meteor readers, I hope you’re getting pumped up for the World Cup finals this Sunday between Spain and England, or, as my husband calls it, Our Original Colonizers versus Our Second Colonizers. I’m rooting for England—but no matter who gets the trophy, the real winners are the record-breaking seven-million-plus viewers who have tuned in to watch women make history.  In today’s newsletter we look at a femicide in Bosnia, check in on Moms for Liberty, and offer up some weekend reading. English for a day, Shannon Melero PS: We’re going to SXSW next spring to have a desperately needed conversation about the state of feminist media. Vote for our panel and leave a comment about what you’d like us to talk about!  WHAT'S GOING ON“We won’t live in fear”: Last Friday, a man in Bosnia went live on his Instagram and shot his former partner, Nizama Hećimović, at point-blank range in the presence of her nine-month-old baby. Over 12,000 people watched the video. Hećimović had filed a restraining order against him just a few days earlier. After broadcasting her murder, the gunman went on to kill two more people, filming his actions all the while before taking his own life. It would be hours before authorities got in touch with Meta to have the footage taken down—but not before it was duplicated and reposted across the internet. As shocking and horrific as this crime is, violence against women has become commonplace in Bosnia. A report on human rights practices in Bosnia and Herzegovina found that “48 percent of women and girls older than 15 suffered some form of gender-based violence” in 2020 and a majority of women—84 percent—didn’t report acts of violence to the police. But Hećimović had reported the harassment by her ex, who had a criminal record. Not only were officials not able to protect her, the Prime Minister had the gall to say in response to her murder that “situations like this cannot be predicted.” Except for when they can. This week, thousands of Bosnians across the country took to the streets in protest, demanding that more be done to protect women from violence, harassment, and femicide. More than that, Bosnians are putting more pressure on Meta to explain how exactly a man was able to live stream three murders before having his account shut down. PROTESTORS IN SARAJEVO, BOSNIA (SCREENSHOT VIA TWITTER) AND:

HAVEN'T SIGNED UP FOR OUR AMBASSADOR PROGRAM? JUST CLICK THE LINK ABOVE TO GET YOUR UNIQUE SHARE CODE AND START EARNING POINTS TOWARD MERCH!  WEEKEND READS 📚On doing too much: Barbie-mania came for every corner of pop culture, even home renovation shows. Here’s how it all went wrong for one California neighborhood. (The Ringer) Online: Dating apps were all fun and games until they became a hunting ground for “con artists, rapists, and murderers.” (Mother Jones) On education: How natural disasters have decimated math scores for young students in Puerto Rico. (NPR) On “girl” things: Womanhood is being repackaged online. A “blogger girl” explains the trend. (Vox) On Scandoval: Rachel is ready to talk. Again. (The Cut)

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? This newsletter was written by Shannon Melero.

|

![]()

A Generation of Women Held Back

|

Dear Meteor readers, Two years ago this week, the United States and Great Britain withdrew troops and diplomatic resources from Afghanistan as the Taliban claimed rule in that country. Since that fateful day in 2021, over 1 million people have fled Afghanistan and some have found themselves displaced, detained, and separated from their families. Many, like Zaki Anwari, died attempting to escape; the devastating images of people hanging from planes while they were taking off remain seared into our minds. Then there are those who stayed or were left behind and have seen their nation impoverished and their rights curtailed. In today’s newsletter, we look at what the last two years have been like for Afghan women and girls—along with that big Trump indictment, some good news in Massachusetts, and more trouble in Texas. With love, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON...IN AFGHANISTAN FAMILIES LINE UP TO BE TAKEN OUT OF KABUL THE DAY AFTER THE TALIBAN RETURNED TO POWER. (IMAGE BY MASTER SGT. DONALD R. ALLEN VIA GETTY IMAGES) Not a “comfortable and prosperous” life: In June of this year, Taliban leader Hibatullah Akhundzada shared a message which claimed that “The status of women as a free and dignified human being has been restored and all institutions have been obliged to help women in securing marriage, inheritance and other rights.” But the difference between reality and propaganda is stark. Beginning in early 2022, girls were banned from attending school beyond the 6th grade. As the year rolled on, women were banned from universities, government jobs, non-government jobs, and eventually all public spaces. Women who want to leave their homes are required to wear burqas and must be accompanied by a male relative. If a man isn’t available, as can easily be the case for widows and divorcees, a woman must remain out of sight. The implications of this oppression are far-reaching. Not only are entire generations of women being denied rights, resources, and access to education, but the national economy is suffering as the countries Afghanistan previously relied on for aid have largely withdrawn their money because of the Taliban’s human rights violations. That loss of aid coupled with several years of drought-like conditions has triggered a near-famine in most of the country. Unable to work outside of the home, women are left to starve or resort to extreme measures to survive. Those who attempt to fight back, like the women who protested the banning of beauty salons last month, are met with more violence. And yet the women of Afghanistan continue to fight. A new report from Sky News reveals that some have created “underground” businesses to help themselves and others earn an income. One business owner who started a secret craft shop used the funds from her business to open an underground school for girls; it now services 200 students. “I don't want Afghan girls to forget their knowledge and then, in a few years, we will have another illiterate generation,” she told Sky News. But without proper government infrastructure or international aid, even the most resilient Afghan woman is up against insurmountable odds. So are some of those who managed to escape the country: In the UK, Afghan refugees are now facing homelessness after a program which paid for their hotel stays ended; those who settled in America dealt with a similar housing crisis last year. The road to the “comfortable and prosperous life” that Akhundzada claimed Afghan women already possessed is as of yet uncharted. It certainly cannot be obtained with the Taliban in power, but with no other group remaining to challenge them the Afghan people have been left with few choices. This morning in Kabul, Taliban soldiers celebrated their triumph with a parade. Click here to donate to relief programs in Afghanistan. For more on Afghanistan feel free to revisit our interview with two Afghan journalists, and our talk with Afghanistan Women’s National team captain, Farkhunda Muhtaj.

AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? This newsletter was written by Shannon Melero and Bailey Wayne Hundl.

|

![]()

The Rhymes That Changed Us

11 Women on Their Hip-Hop Click Moment

By Rebecca Carroll

Hip-hop as a genre is complicated. But at its core, it’s about bearing witness to the world and telling a story directly from that personal vantage point. Whether they be stories of revolutionary rage, tender triumph, sheer joy, or all of the above, the hip-hop canon is undeniably rich. This year marks the 50th anniversary of hip-hop as an art form, and to celebrate, we asked our favorite creatives to share a lyric from one song that impacted them in some profound way.

It could all be so simple

But you’d rather make it hard

Loving you is like a battle

And we both end up with scars

I write to music. I look for songs that open me up to the emotions I’m writing. These lyrics are so deep and gutturally poetic. I put this song on repeat to write the “fourth quarter” of Love and Basketball. I have literally heard it over a thousand times. And it rocks me still. —Gina Prince-Bythewood, filmmaker

And since we all came from a woman

Got our name from a woman and our game from a woman

I wonder why we take from our women

Why we rape our women, do we hate our women?

I spent some time with Pac before this song was written. I was in a black feminist rock group called Subject to Change. He would come to my band rehearsals, and afterwards we would share deep and heavy conversations about the depiction of Black women in Hip Hop. We also talked about the incredible women of The Black Panther Party. My heart expanded when he wrote these powerful lyrics. He was such a beautiful man inside and out. —Cree Summer, actress, singer/songwriter

You ain’t a bitch or a hoe

I've been a hip-hop fan since I was a little girl, but I've always resented how misogynistic the music can be. I didn't have the greatest understanding of why that was when I was small, but I knew that our men were using it to call us mean names and I didn't like that. When I was about nine, Queen Latifah released “U.N.I.T.Y.,” a powerful clapback towards sexism in both hip-hop music and the Black community. I was entranced. Latifah was so strong, so beautiful, and she was standing up for us. It's one of my favorite songs to this day. —Jamilah Lemieux, cultural critic

Hypocrites always wanna play innocent

Always wanna take it to the full-out extent

Always wanna make it seem like good intent

Never wanna face it when it's time for punishment

I know you don't wanna hear my opinion

There come many paths and you must choose one

And if you don't change then the rain soon come

See you might win some, but you just lost one

She is perfect here, and ruthless. —Danyel Smith, author

I push my seed in her bush for life

It's gonna work because I'm pushing it right

If Mary drops my baby girl tonight

I would name her "Rock n' Roll"

— “The Seed,” The Roots ft. Cody Chestnut

When my husband Chris (a former DJ, and a pretty serious hip-hop head) and I were first dating, he made a number of playlists for me. Often I’d listen to them on my own, at the gym or whatever, but one time he made a playlist for me that we listened to for the first time together in the car on our way out of town for a weekend getaway. When “The Seed” by The Roots with Cody Chestnut—which I’d never heard before—came on, I was immediately feeling it. But when I heard this hook, I absolutely fell in love with it (and, to be honest, with Chris). I turned to him and said, “That’s the most beautiful thing I’ve ever heard.” Reader, it is of no small significance that on our first date, before we were even brought menus, I’d told him I wanted to have a baby within the next year or two, and then said, directly, “So what are you looking for in a relationship?” He responded, unrattled, “Why don’t we have dinner first.” He planted the seed in my bush for life 10 months later. We named him Kofi. —Rebecca Carroll, writer and Meteor editor-at-large

Word up, mommy. I love you — Ghostface

I sit and think about

All the times we did without

I always said I wouldn't cry

When I saw tears in your eyes

I understand that daddy's not here now

But some way or somehow, I will always be around — Mary J. Blige

— “All That I Got is You,” Ghostface Killah ft. Mary J. Blige

Ghostface is in my top 10, but this song is easily in my top five. When I hear the raw honesty, vulnerability, love, and pain in his voice, I cry thinking about my three sons. Though Pretty Toney’s circumstances and lived experiences are different from my sons’, I listen and imagine how they are processing their dad’s death, his irrevocable absence, in the quiet hours of the night when they’re in their beds.

Do they cry? Are they angry? Will they heal? What will they remember? Am I enough?

It is excruciating for me to live this life without my husband, my best friend, my greatest love. It pains me to think about my sons navigating this life without their father, the man who loves them most in this world—the person who would have laid down his life for them without thought.

But I hope every day that my sons know I’m doing my best and that I love them with every cell in my body and every beat of my heart. I hope they know I will always, always be around—in this life and the next. And that I will fight beside them to make it through.

Thank you, Ghostface and Mary J., for this prayer. —Kirsten West Savali, VP Content at iOne Digital & cultural critic

Stuntin’ on these bitches out of motherfuckin' spite

Ain't no runnin' up on me, went from nothin' to glory

I ain't tellin' y'all to do it, I'm just tellin' my story

I don't hang with these bitches 'cause these bitches be corny

And I got enough bras, y'all ain't gotta support me

The pressure on your shoulders feel like boulders

When you gotta make sure that everybody straight

Bitches stab you in your back while they smilin' in your face

Talking crazy on your name, trying not to catch a case

I waited my whole life just to shit on ***

Climbed to the top floor, so I can spit on ***

My mom, who has been a preacher in The Bronx my whole life, would regularly tell kids in the congregation, “Great things have come out of The Bronx, so don’t let anyone stop you from doing what you want to do.” She gave me a similar sermon the first time I left home for college, but it was also the first time she went into detail as to all the ways I was about to discover how I was different from the students at my new predominantly white school. When I first heard this song, I felt such a swell of pride—not only because Cardi and I were from the same borough, but because it really captured how I felt about the journey to my own personal “top floor.” Plus it felt good to be honest that I also do certain things purely out of spite for people who told me I’d never get anywhere. —Shannon Melero, writer and Meteor newsletter editor

Yo, my men and my women,

Don't forget about the dean, Sirat al-Mustaqim

Talking out your neck sayin' you're a Christian

A Muslim sleeping with the gin

— “Doo Wop (That Thing),” Lauryn Hill

I remember the first time I heard this song. I was raised Muslim and there weren't any references to my religion in pop culture at the time. I felt so seen to know that an artist, especially Lauryn Hill, knew about Islam. And I was mesmerized by the way she wove it into a song about relationships and self-worth. I listened to the song over and over, and loved hearing it on the radio thinking (and hoping) how many people were noticing those same lyrics. I don't recall the exact moment or song that made me a music head, but putting these words down—this may have been the moment I realized the power of words. —Ayesha Johnson, Meteor director of operations

Pull up in the monster, automobile gangsta

With a bad bitch that came from Sri Lanka

— Nicki Minaj's riff on “Monster”

This lyric always hypes me up if I'm feeling nervous about performing as a DJ or in my work as an activist/advocate. As someone who is from that particular place and does a multiplicity of things that fundamentally, to me, are about care, building power, and creating joy in a world that often doesn't care for BIPOC and queer folks, I like the power of the lyric. It feels like she wrote that specifically for me. —Thanu Yakupitiyage (DJ Ushka), DJ & activist

I put my lifetime in between the paper’s lines

Prodigy’s vivid, cinematic lyricism struck a deep chord in me as a young poet coming of age in the ‘90s and as fate would have it, I later wound up authoring his memoir My Infamous Life with him. This line from “Quiet Storm” encapsulates so much about the power of storytelling—and reminds me of how, at its best, hip-hop transcends boundaries, unites us as a culture and force to be reckoned with, and has made so many poets' dreams literally come true. —Laura Checkoway, filmmaker

We used to fuss when the landlord dissed us

No heat, wonder why Christmas missed us

Birthdays was the worst days

Now we sip champagne when we thirsty

—“Juicy,” The Notorious B.I.G.

In 1996, I went to college a beleaguered student who had gotten into college by the skin of my teeth. I wasn’t a great student, but I had also felt deeply misunderstood and overlooked in my predominantly white suburban school. My life and Biggie’s life were not the same, at all. But his rags-to-riches anthem spoke to me at 18, a young woman of color with a chip on my shoulder and something to prove. His music had such an impact on me that I wrote my senior thesis on how to be a feminist and rap music fan. (tl;dr: my findings were inconclusive) A problematic fave, no doubt, but his music resonates with me to this day. —Samhita Mukhopadhyay, writer and Meteor editorial director