What We All Need to Know About the Executions in Iran

"This is androcide."

Just three days ago, Iranian news agencies confirmed the execution of another man. As far as reliable sources are able to confirm, he appears to be the 33rd person executed by the state in 2023.

As the regime continues to crack down on protestors who have taken to the streets after the death of Mahsa Amini, I spoke to Sherry Hakimi, policy advisor and executive director of genEquality about what’s really happening—and what, if anything, we can do.

Shannon Melero: What exactly does the international community need to know about the executions of protestors happening in Iran?

Sherry Hakimi: The Islamic Republic has long used execution as a violent tactic for suppressing dissent. Even before the recent revolutionary movement, executions had been rising in Iran: In 2022, the number reportedly surpassed 400 before the September protests began; in 2021, there was a 20% increase in executions over 2020, mostly on drug-related offenses.

According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, these executions break international human rights law by violating due process and fair trial guarantees. The violations include the use of vaguely worded criminal provisions, denial of…the right to present a defense, forced confessions obtained through torture and ill-treatment, failure to respect the presumption of innocence, and denial of the right to appeal.

What are these people being charged with that is so severe their government believes it warrants death?

To be clear, these are charges made in sham judicial processes. Currently, the common charges are murder of [Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps officers], “moharebeh” (“waging war against God”), and “mofsed-e-felarz” (“corruption on earth”).

The people who have been executed to date have been found guilty of murder on the basis of what can only be called coerced confessions. As for “moharebeh” and “mofsed-e-felarz,” these are catch-all charges that the Islamic Republic often levies on anyone who goes against them.

It’s important to recognize that from whatever angle you look at it—judicial, political, social, moral—these executions are illegitimate and must be stopped.

Is there a reason that the executions we’re aware of have been men? I think in general we understand that this revolution began with and about women, and yet that’s not who we are seeing receive these harsh punishments.

First, I have to disagree with the implication that women aren’t receiving harsh punishments. There are reportedly more than 19,000 people currently held in Iran’s jails, and there have been numerous reports of Iranian women being brutally beaten, tortured, raped, disfigured, and murdered by regime forces. Going through a sham judicial process before being brutalized or murdered does not lessen the harshness of either.

The atrocities experienced by women—namely, brutal rape and sexual assault—are violent, gruesome atrocities that will haunt and adversely affect those women for the rest of their days, leaving them psychologically, emotionally, and often physically scarred. I am in no way diminishing the severity of execution, but rather, elevating the severity of rape and sexual assault to the level at which it should be considered. Both execution and rape are unacceptable and inhumane tools of war utilized by primitive brutes. These acts have no place in today’s world.

A few points come to mind as to why we’re seeing more men face execution. First, there’s very little (if any) reason to believe a single one of the charges levied against any detained protester, but the four men who have been executed to date were all charged with murder. It’s possible that the Islamic Republic, in keeping with its patriarchal ways, thinks it is somewhat more plausible to pin false murder charges against male protesters.

Second, although Iran is one of the world’s biggest perpetrators of the death penalty (second only to China) [with] the distinction of having executed the most women to date, women generally make up a small percentage of the people who are executed each year everywhere. (According to the Death Penalty Information Center, women make up 1.2% of the people who have been executed since 1976 in the U.S.) It’s possible that we’re seeing a similar dynamic play out in Iran. All protesters and detainees face brutal and indiscriminate beating and torture. Women disproportionately experience brutal assault and rape, and men disproportionately are handed execution sentences.

Third, this is indeed a female-led revolution, but the protesters are not solely women. From the beginning, we have lauded the fact that Iranian men and boys have been out there, shoulder to shoulder, protesting alongside Iranian women and girls.

Lastly, it’s likely not an accident that the four men executed to date and the dozens of others who face imminent execution include a karate champion, a bodybuilder, a doctor, a popular rapper, etc. In instances of war and conflict, both international and domestic, there is a history of aggressors targeting strong, skilled men and boys. This is androcide: when one side of a conflict sees its opposing men, fighting or otherwise, as rivals and a threat to their superiority and thus sets out to kill the rivals and neutralize the perceived threat. Frankly, only a country led by weak and insecure brutes treats its own people as the enemy and wantonly subjects them to violence and death.

Is there anything people outside of Iran can do to help? Is there something specific the American government should be doing?

This revolutionary movement is ongoing, and the plea of Iranian protesters is for everyone outside of Iran to be their voice. To that end, one of the most helpful things that people can do is to keep posting about Iran across their social media channels. This is the rare case in which posting about an issue on social media is not “slacktivism,” but rather, proper activism. You can also join protests, speak with friends about what’s going on in Iran, and generally use every opportunity to spread awareness of the Iranian people’s fight for women, life, and freedom.

Revolutions are unpredictable, but the Islamic Republic regime is unlikely to fall quickly. To that end, both the U.S. and the international community need to have short-term and long-term plans. Short-term actions include announcing targeted sanctions on Islamic Republic leaders, appropriately reducing the Islamic Republic’s legitimacy in multilateral institutions like the UN, and increasing civic technology access; long-term actions include mobilizing needed humanitarian aid, emergency medical services, and greater international accountability mechanisms.

One thing that we really haven’t been talking about—but we should—is that as Iranian protesters are being brutalized, there are lives, limbs, eyes, and more being needlessly lost due to a lack of medical care. I believe that international leaders (by “international leaders,” I mean every country in the world, as well as the United Nations, World Health Organization, Red Crescent, Doctors Without Borders, and the like) need to think harder and more innovatively about what aid and support they are providing to Iranian protesters. Getting emergency medical services into Iran will be a challenging task, but it is still an effort that should be made, preferably as noisily as possible. I would really like to see more people calling on the various humanitarian/health organizations to step up efforts to help Iranians who are fighting for freedom.

When Dr. King Talks to Me, This is What He Says

A home for modern feminism

Reflections on the words you know and the ones you don't.

BY REBECCA CARROLL

January 12, 2023

I grew up in New Hampshire, which was the last state in the country to observe Martin Luther King, Jr. Day as a holiday (kicking and screaming, at that; they held out until literally the year 2000, almost two decades after federal legislation making it a national holiday was passed).

At home, though, my white adoptive parents told me the words and leadership of Martin Luther King, Jr. made them feel encouraged about adopting and raising a Black child. “We believed in his message about people of all races coming together,” my mom liked to say.

To which I responded, on more occasions than I’d like to recount, that first of all, it was a dream. People of all races weren’t exactly unified when King made his “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963—the year Medgar Evers was murdered, the KKK killed four little Black girls at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, and tens of thousands of folks marched on Washington for their basic civil rights.

And second of all: He was killed because of that dream.

My parents’ interpretation of King’s message felt willfully naive to me. But it is not uncommon for white liberals then or now to pride themselves on just knowing who he is while conveniently forgetting how radical his message was at the time of his assassination—particularly following his public denouncement of the Vietnam War in a speech given at the Riverside Church in Manhattan. Up to that point in 1967, most Northern liberals felt pretty OK about supporting King’s fight for civil rights on American soil. But when it came to people of all races in other parts of the world? Not so much. (King also committed the cardinal sin of pushing back against American military power, considered unpatriotic then and now.) The media went nuts. In a piece called “Dr. King’s Error,” The New York Times, a notable ally of King’s, called his speech “both wasteful and self-defeating.”

But his words, the famous and less-famous ones, continue to exist and reverberate in the world. It’s odd to miss people you’ve never met (much less public figures or historical icons) but when I reread some of King’s words, I miss him. I miss the extraordinary power and passion of his focus and his love for us in real time. I often wonder if he could have imagined how the things he said amid great struggle and duress would decades later be cut, spliced, removed from their context, and posted on Instagram. I wonder if he could guess that there would be a generation that knows him better for his quotes than for the fact that he helped get a law passed authorizing the federal government to treat me—and people of all races—equally.

If we are going to keep lionizing his quotes, though, then MLK Day (now recognized nationally) is a good time to look at a few of them more closely and reconsider the ways they still hold meaning. Here are a few that resonate with me:

“History will have to record that the greatest tragedy of this period of social transition was not the strident clamor of the bad people, but the appalling silence of the good people.”

The strident clamor of the bad people still be stridently clamoring. (Two words for you: January 6th.) And as we face some of the most vicious attacks on our rights, the “appalling silence of the good people” continues to damage and divide us as a nation. The U.S. Supreme Court eliminated the constitutional right to abortion. There were over 600 mass shootings documented in 2022. Voter suppression is still rampant. And while I am heartened by those who do speak out and protest, most people, even those who consider themselves fair-minded, choose to remain silent. That astonishes me.

“Discrimination is a hellhound that gnaws at Negroes in every waking moment of their lives to remind them that the lie of their inferiority is accepted as truth in the society dominating them.”

Still holds. I don’t think even the most well-intentioned white people understand that America’s default settings—the standards of all that we know and have codified into the canons of literature, beauty, education, moral codes, and societal behavior—is a made-up truth devised to make non-white people, specifically Black people, feel less than across the board.

“I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be. This is the interrelated structure of reality.”

In other words, your acts of oppression are oppressing us both.

“Make a career of humanity. Commit yourself to the noble struggle for equal rights. You will make a better person of yourself, a greater nation of your country, and a finer world to live in.”

Will it, though? I wrestle with this line of Dr. King’s. I have committed myself to the struggle throughout my entire life and career—and it doesn’t always feel noble. A lot of times, it just feels exhausting. King was not wrong about the struggle making you a better person, but being a better person doesn’t automatically mean the world changes. That’s the throughline—for all of King’s grace, fortitude, and elegant militance, he placed his faith in a universal humanity that did not exist then and does not exist now.

But I suspect King knew that as well. If America could have its own version of humanity, then why couldn’t he have one, too? One that doesn’t demolish the other version, but rather helps to rehabilitate it? As his daughter Bernice King has reminded us in her own tireless efforts at carrying on King’s legacy: “My father literally fought his entire life to ensure the inclusion of all people because he understood that we were intertwined and connected together in humanity.”

I guess that’s ultimately what keeps me in the struggle: a version of humanity that is fueled by compassion and sustained by the truth of our existence. And I will chase down that version until it no longer needs to be imagined. As King himself said, “We must accept finite disappointment, but never lose infinite hope.”

Before You Post That MLK Quote

|

Hey there, Meteor readers, I didn’t make a lot of resolutions for 2023. I’m about to have a child, and I hear they really derail any and all of your plans. But one thing that was on my goal list was to find a daily affirmation to carry throughout the year—and by George, I think I’ve done it. On Tuesday, the love of my life, Michelle Yeoh, told an entire orchestra, “I can beat you up, okay? And that’s serious,” when it tried to interrupt her length-appropriate acceptance speech for Best Actress at the Golden Globes. This is the energy I want to maintain for the rest of the year—whatever comes at me, whether it be a minor inconvenience or an entire Hollywood orchestra, I can beat it up. And that’s serious!  In today’s newsletter, we revisit the words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.—and not just the ones you already know. Instead, Meteor editor-at-large Rebecca Carroll takes a closer look at King’s writing, and how it moves her today. But before that, a touch of news. Channeling Michelle, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON“Compromising” on abortion: Virginia Republicans have introduced what they’re calling a “moderate” and “reasonable” abortion bill that would criminalize abortion after 15 weeks in that state. But as we used to say at my old job, the proof is in the paperwork; what’s being touted and what’s actually written in the bill are two entirely different things. Slate’s Mark Joseph Stern points out that, among many other glaring issues, this bill criminalizes abortion before viability can be determined—meaning if a patient discovers at 17 weeks that their fetus cannot survive outside the womb, they are legally obligated to carry that pregnancy to term unless it will literally kill them. And even the exception for the life of the pregnant person is written in such a way as to discourage doctors from performing life-saving procedures. Stern writes that while the bill would allow doctors to do an emergency abortion after 15 weeks, using their medical judgment they are, “subject to incarceration if prosecutors disagree with their assessment and a jury determines that the abortion was unnecessary.” This isn’t much more moderate than the Texas abortion ban that led to Amanda Zurawski nearly dying of sepsis because her doctors were legally unable to act quickly enough. Stern writes that many patients have been “forced to the brink of death” because there are so many medical issues that can “harm pregnant patients without guaranteeing their death.” And under H.B. 2278, doctors have no choice but to wait until death is imminent. What an interesting way to approach law making from the party that claims to value life the most. AND:

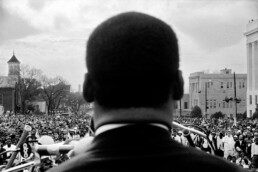

EXAMINING A LEGACYWhen Dr. King Talks to Me, This is What He SaysA reflection on the words you know and the ones you don't. BY REBECCA CARROLL  DR. KING ADDRESSING A CROWD IN ALABAMA. (IMAGE BY STEPHEN SOMERSTEIN VIA GETTY IMAGES) I grew up in New Hampshire, which was the last state in the country to observe Martin Luther King, Jr. Day as a holiday (kicking and screaming, at that; they held out until literally the year 2000, almost two decades after federal legislation making it a national holiday was passed). At home, though, my white adoptive parents told me the words and leadership of Martin Luther King, Jr. made them feel encouraged about adopting and raising a Black child. “We believed in his message about people of all races coming together,” my mom liked to say. To which I responded, on more occasions than I’d like to recount, that first of all, it was a dream. People of all races weren’t exactly unified when King made his “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963—the year Medgar Evers was murdered, the KKK killed four little Black girls at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, and tens of thousands of folks marched on Washington for their basic civil rights. And second of all: He was killed because of that dream. My parents’ interpretation of King’s message felt willfully naive to me. But it is not uncommon for white liberals then or now to pride themselves on just knowing who he is while conveniently forgetting how radical his message was at the time of his assassination—particularly following his public denouncement of the Vietnam War in a speech given at the Riverside Church in Manhattan. Up to that point in 1967, most Northern liberals felt pretty OK about supporting King’s fight for civil rights on American soil. But when it came to people of all races in other parts of the world? Not so much. (King also committed the cardinal sin of pushing back against American military power, considered unpatriotic then and now.) The media went nuts. In a piece called “Dr. King’s Error,” The New York Times, a notable ally of King’s, called his speech “both wasteful and self-defeating.”  DR. KING BEING RUSHED BY A MOB OF PROTESTORS WHO WERE FOR THE VIETNAM. (IMAGE BY JACK SHEAHAN VIA GETTY IMAGES) But his words, the famous and less-famous ones, continue to exist and reverberate in the world. It’s odd to miss people you’ve never met (much less public figures or historical icons) but when I reread some of King’s words, I miss him. I miss the extraordinary power and passion of his focus and his love for us in real time. I often wonder if he could have imagined how the things he said amid great struggle and duress would decades later be cut, spliced, removed from their context, and posted on Instagram. I wonder if he could guess that there would be a generation that knows him better for his quotes than for the fact that he helped get a law passed authorizing the federal government to treat me—and people of all races—equally. If we are going to keep lionizing his quotes, though, then MLK Day (now recognized nationally) is a good time to look at a few of them more closely and reconsider the ways they still hold meaning. Here are a few that resonate with me:

The strident clamor of the bad people still be stridently clamoring. (Two words for you: January 6th.) And as we face some of the most vicious attacks on our rights, the “appalling silence of the good people” continues to damage and divide us as a nation. The U.S. Supreme Court eliminated the constitutional right to abortion. There were over 600 mass shootings documented in 2022. Voter suppression is still rampant. And while I am heartened by those who do speak out and protest, most people, even those who consider themselves fair-minded, choose to remain silent. That astonishes me.

Still holds. I don’t think even the most well-intentioned white people understand that America’s default settings—the standards of all that we know and have codified into the canons of literature, beauty, education, moral codes, and societal behavior—is a made-up truth devised to make non-white people, specifically Black people, feel less than across the board.

In other words, your acts of oppression are oppressing us both.

Will it, though? I wrestle with this line of Dr. King’s. I have committed myself to the struggle throughout my entire life and career—and it doesn’t always feel noble. A lot of times, it just feels exhausting. King was not wrong about the struggle making you a better person, but being a better person doesn’t automatically mean the world changes. That’s the throughline—for all of King’s grace, fortitude, and elegant militance, he placed his faith in a universal humanity that did not exist then and does not exist now. But I suspect King knew that as well. If America could have its own version of humanity, then why couldn’t he have one, too? One that doesn’t demolish the other version, but rather helps to rehabilitate it? As his daughter Bernice King has reminded us in her own tireless efforts at carrying on King’s legacy: “My father literally fought his entire life to ensure the inclusion of all people because he understood that we were intertwined and connected together in humanity.” I guess that’s ultimately what keeps me in the struggle: a version of humanity that is fueled by compassion and sustained by the truth of our existence. And I will chase down that version until it no longer needs to be imagined. As King himself said, “We must accept finite disappointment, but never lose infinite hope.”  JOIN US!It’s been six months since the Supreme Court of the United States overturned Roe v. Wade. We are living through a once-in-a-generation moment around reproductive freedom. So where do we go next in 2023, particularly when we know that it will be birthing people of color who will experience the most harm in this moment? On Wednesday, January 18th–just ahead of what would have been the 50th anniversary of Roe v. Wade—The Meteor will host Roe At 50: Abortion Access From Now On. This virtual briefing will feature a conversation with Renee Bracey Sherman, founder & executive director of We Testify and co-author of the forthcoming book, Countering Abortionsplaining; and Brittany Packnett Cunningham, award-winning activist and the host of UNDISTRACTED; moderated by Regina Mahone, senior editor at The Nation and co-author of Countering Abortionsplaining. To learn more and register for this FREE virtual event, click the button below.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Iran Will Execute More Protestors

January 10, 2023NEWS,NEWSLETTER

|

Top of the evenin’ to ya, Meteor readers, I am in a mildly jovial mood as I write this because this newsletter is our 100th edition. Can you believe it? It feels like just minutes ago we were deconstructing Pam and Tommy and wondering what might happen if Elon really did buy Twitter. Simpler times, no?  In today’s centenary newsletter, we return our attention to Iran, which slipped from headlines while Kevin McCarthy and his drama were sucking up all the air in the room. Plus some other news you might have missed. For the (literal) hundredth time, let’s get into it. With an attitude of gratitude, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONExecutions in Iran: As protests continue, day-by-day conditions are worsening for those fighting for freedom. Four men were executed by the state after being arrested at protests, and 12 more have been sentenced to death. Their crimes? “Waging war on God,” or in layman’s terms, going against a theocratic government that runs on willful and violent misinterpretations of religion. At present, the total number of Iranians sentenced to death is believed to be 41 (but could be higher). While most of those sentenced to death have been men, women also continue to suffer under the regime’s crackdowns on protestors, facing arrests and both physical and sexual violence. According to WIRED, the Iranian government is also able to use facial recognition software to identify anyone breaking hijab laws. These protests are no longer focused only on the death of Mahsa Amini and the unequal treatment of women. Several Iranians who spoke to The Washington Post anonymously explained that they are fighting for “cultural and political freedom” for all and against the “economic mismanagement” of the current regime. One man, whose family was priced out of Tehran, told the Post, “I feel rage, rage and a lack of hope. It’s desperation…If we go out to protest, they crack down in the worst and most reprehensible way. We really don’t know what to do. We can’t protest. We can’t improve our situation.” As outsiders, we’re seeing the ingredients come together for a slow-moving, long-lasting, and life-altering revolution: Political unrest, economic distress, and religious contention all crashing up against each other until, eventually, the people become too powerful to contain. But this shift in power won’t happen overnight. As journalist Neda Semnani wrote in a previous newsletter, “We must acknowledge that in order for this revolution to succeed, many brilliant, beautiful, and brave human beings will give up their futures for someone else’s. We must acknowledge their suffering, their fears, and most of all, the lives they won’t get to live. We must also acknowledge the people they leave behind and the pain those who will survive will carry with them. This is what it means to resist and to revolt. It means that one group will sacrifice their plans, their potential, and all their normal mornings so that perhaps, one day soon, the rest of us might revel in freedom.” AND:

The United States has the shortest paid parental leave policy of any wealthy nation in the world, with a whopping ZERO weeks of guaranteed paid leave for workers. FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays. Ideas? Feedback? Requests? Tell us what you think at [email protected]

|

![]()

Why the Congressional Sh*tshow Matters

January 5, 2023NEWS,NEWSLETTER

|

Hey there, Meteor readers, The first week of January is almost over; how are those resolutions coming along? Yeah. Mine too. Tomorrow, as we all know, is the two-year anniversary of the January 6 insurrection. I can’t remember what I had for breakfast this morning, but I can still remember that day when someone told me there was a riot at the Capitol and I simply responded, “No, there’s not.” A few moments later we were watching it unfold on CNN: thousands of people violently rushing into the Capitol building demanding that Mike Pence and Congress reject the results of the 2020 election. Jan. 6 was a turning point in American history and politics. A group of people had a completely different understanding than most of the country of how democracy should work and they were being goaded on by a sitting President. Alarmingly, not much has changed to ensure something like this can’t happen again. Yes, arrests were made and prison sentences were handed down to rioters—but election deniers still hold positions of power. More than ever ran for office in 2022 (though many lost). Donald Trump, who reveled in the event, still talks about a presidential run despite the January 6 Committee recommending he face criminal charges. We are truly in the Upside Down. In today’s newsletter, we get into this year’s big mess, Kevin McCarthy, the latest on Andrew Tate, and a touching note from one of you. (If you’ve never sent us a message, try doing something new this year!) Wondering how two years went by so fast, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONDon’t speak: It’s been a bad week for Representative Kevin McCarthy, who lost ten different rounds of voting in his attempt to become Speaker of the House. The fact that his own party is responsible for making McCarthy a national embarrassment is the kind of true-life comedy Judd Apatow wishes he could write. But beyond the extremely good tweets this event has produced (including this IG post) lies a more serious problem. The 118th Congress can’t be sworn in until a Speaker has been chosen, which means that because of this right-wing nonsense, the country has been running without a functional House all week (although how functional it’ll be when this all gets sorted is a question for another day). So while we’re all enjoying a hearty laugh over this man’s desperation to get some votes (and some pizza), let’s not forget we need this matter to be resolved to get on with the work of governing. As Amanda Marcotte explained in Salon, it’s not really about McCarthy: “It's about the Republican Party's self-conception in its exciting new fascist iteration (which was forged under Donald Trump but doesn't really have much to do with him either).” In order for fascism to flourish, Republicans must, Marcotte writes, “bully” and “ritually purge a once-trusted insider” who’s failed to fall in line with the group. What will the GOP choose? Implosion or compromise? My money’s on the former.  WHEN THE JOKE'S NOT THAT FUNNY BUT YOU KNOW THERE'S ANOTHER VOTE COMING. (IMAGE BY CHIP SOMODEVILLA VIA GETTY IMAGES) More than words: During a televised conference on state-run IRNA news, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei of Iran made a comment about hijab that we’re extremely skeptical about: “Hijab is undoubtedly an inviolable necessity, but this inviolable necessity should not cause those who do not fully observe hijab to be accused of being irreligious or counter-revolutionary,” he said to a room full of women. The comment was an attempt, after four months of protests over the death of Mahsa Amini, to hint at some sort of directional shift or leniency on the government’s treatment of those not observing their interpretation of hijab. But given that the same government has handed down 26 death sentences for those who have been arrested at the protests, it’s not particularly inspiring anyone to believe that change is on the way. It gets worse: Two women have come forward against influencer Andrew Tate claiming they were abused by him in the UK in 2015 and their cases were allegedly mishandled by UK police and Crown Prosecution who failed to bring any formal charges against Tate. (Not only was he not prosecuted, he was on Big Brother UK during the investigation.) According to Vice, Tate was arrested on suspicion of sexual assault and physical abuse and was eventually released while the investigation into the women’s claims took four years to be handed over to CPS. During that time, Tate was allegedly running a “webcam sex business” with his brother. AND:

OPENING OUR INBOXThis week we got an absolute gem of a letter from newsletter reader Sean who writes: Let me first start by stating that my 24-year-old daughter is amazing!! I want her life to have an equal opportunity for happiness, health, career satisfaction, respect, and choice for her future life decisions. She is the reason I started reading your articles. In fact, she is the reason I’m able to love without boundaries. I believe that these freedoms dictate the ability to truly express love. And I don’t want a world where authentic love is stifled. I want love to abound....I want the most authentic love attainable for me, and all others. This defines a healthy world. Commonality is found across the globe (based on this). I commend your education, to men like me, through thoughtful articles. Sean, we’re so happy that you’ve found your way to us. And aren’t you a lucky guy for having an amazing daughter. Thanks so much for reading!  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays. Ideas? Feedback? Requests? Tell us what you think at [email protected]

|

![]()

We're Getting In on the In/Out Trend Too

January 3, 2023NEWS,NEWSLETTER

|

Felicitous new year, Meteor readers, Wow, we’re back at it again in 2023. I, for one, have been in a time freeze since the last time we chatted. The Meteor is coming off of a seven-day vacation during which I chose to live my best life—and by that, I mean I reorganized my closet and played several hours of God of War: Ragnarok. (She’s a gam3rgrl.) I hope your end-of-year was just as exciting.  In today’s newsletter, we’re easing ourselves into 2023 with our own version of what’s in and what is absolutely out (*cough* low-rise jeans *cough*). But first, let’s take a look at the news. Typing from the floor of my extremely clean closet, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONBirth behind bars: According to the Arizona Republic, Perryville prison induced three incarcerated women before their due dates without their consent. While induction is safe in most cases, doing so before a due date is a decision between a patient and a care provider—and the women told reporters that they were not given the choice to refuse induction, and would have preferred to give birth without it. They’ve also claimed that prison medical providers insisted that the inductions were part of Arizona Department of Corrections policy—most likely as a way to decrease the prison’s liability—rather than a medical necessity, bringing an entirely new and frightening meaning to forced birth. (The ADOC did not comment on the situation, but NaphCare, the medical contractor working with the prison, denied the existence of any such policy.) One of the women, Stephanie Pearson, told the Republic, “They just told me that someone on a different yard a few years ago went into labor in their cell, and had their baby in the cell, and that's why they induce everyone now.” Desiree Romero, who was also induced, said she wasn’t surprised that she wasn’t being given any choices: “I’m quite used to the prison making all these decisions for us because we are still state property.” AND:

MARTINA PRESENTING THE WOMEN'S SINGLES CHAMPIONSHIP TROPHY AT LAST YEAR'S US OPEN. (IMAGE BY DIEGO SUOTO VIA GETTY IMAGES)

THE LAST IN/OUT LIST YOU'LL NEED THIS YEAR You know what's always in? Winning free stuff. We're giving away tote bags to the first 10 people to click on the image below just as a thank you for sticking with us into the new year.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays. Ideas? Feedback? Requests? Tell us what you think at [email protected]

|

![]()

Your Favorite Meteor Stories of 2022

December 30, 2022NEWS,NEWSLETTER

Happy (almost) New Year, dear Meteor reader,

It’s almost our anniversary—yours and ours. In January, Meteor founding member Jennifer Finney Boylan wrote the first feature essay of the Meteornewsletter—and it’s been a thrilling journey ever since. So much has happened this year, and who better to celebrate with than you?

First, a round of applause to Meteor collective members who had astounding years. There were books: Supreme Court commentator Dahlia Lithwick released her much-anticipated Lady Justice; Amber Tamblyn’s Listening in the Dark taught us to trust our intuition; and Julissa Natzely Arce Raya’s latest, You Sound Like a White Girl, acted like medicine unto the bones.

And there were prizes: Rebecca Carroll snagged three Webbys for her show “Billie Was a Black Woman,” Salamishah Tillet won a Pulitzer for distinguished criticism, Dawn Porter showcased the heroes of Title IX, and our podcast “Because of Anita” got a Gracie. It’s giving…

Meanwhile, in a year that came with some challenges, it meant a lot to us to tell stories that resonated with you on the issues that matter. Projects like the “My Abortion Story” series, the viral Josh and Amanda Zurawski interview, Talia Kantor Lieber’s student investigation into colleges paying (or not paying) for abortion travel, and live events like 22 For ‘22 and Meet the Moment where we got to meet some of you, in the flesh, for the first time.

It was also an emotional year on our podcast “UNDISTRACTED” with some amazing episodes: the most important conversation about RENAISSANCEever, an analysis of the Great Resignation with Elaine Welteroth, and who could forget the touching dialogue between host Brittany Packnett Cunningham and her husband, Reginald, about the birth of their son, who was delivered at just 24 weeks. Some of us are still crying about that one. (It’s me, I’m us.)

Of course, I would be remiss if I didn’t shout out the highlights of my favorite part of The Meteorverse: this newsletter right here, powered by all of you. Thank you, readers, for every open, every click, and every time you’ve forwarded our stories to someone you know. It means the world to us. And if you are so inclined to continue sharing The Meteor with your friends, family, enemies, exes—anyone you want, we don’t judge!—here’s a list of our top 10 newsletters this year as decided by you, the all-powerful arbiters of interesting.

10. Muslims Are Not a Monolith

9. “If they could kill her, they could kill anyone.”

8. Queen Elizabeth’s Complicated Legacy

7. How Our Data Is Used Against Us in the Post-Roe World

6. The Best (and worst) Parts of the KBJ Hearings So Far

5. The Supposed Death of #MeToo

4. When “Feminists” Spout Hate

2. Puerto Rico’s Dimming Future

The entire Meteor team wishes you a gentle and restful new year. We’ll see you here, in your inbox, in 2023. And we’ll keep bringing you the news and stories you want to know about with a full serving of feminist perspective—and a splash of dry wit—to keep things interesting.

For auld lang syne,

Shannon Melero

What We Can Do for Abortion in 2023

|

Dear Meteor readers, I’ve officially started the process of shutting down my brain (watching Emily in Paris; let me live) and getting ready to unplug for the rest of the year. I hope you’re doing the same. But before we enter the land of holiday snacks and midday naps, we have a few more really special sends for you. Today, my colleague Cindi Leive writes about abortion—what she’s learned from years of covering it and how not to repeat the mistakes of the past. But first, a little news—about Ukraine, lady governors, and menopause visibility. Merry merry, Samhita Mukhopadhyay  WHAT'S GOING ONHistoric visit: If you haven’t yet, it’s worth reading/listening to the powerful, funny, and historic plea President Volodymyr Zelensky made before Congress yesterday. Our own teammate Anya Kurkina, whose family is in Kyiv, told us, “As a Ukrainian living in the US, I felt an immense sense of pride watching Zelensky address the nation. He holds the weight of world peace on his shoulders, and we are determined to stand behind him and the European people every inch of the battlefield. Peace will have to be won. He understands the value and the price of it.” New cruelty in Afghanistan: The Taliban has officially banned women from attending university. There had already been a ban on teen girls attending high school, but this new announcement will deny those who have already graduated access to higher education. This move is devastating to Afghan women, who said they were shocked by the decision. AND:

EDITOR'S NOTEBOOKThe Abortion Stories I Wish I’d ToldOur personal experiences matter, but the media (including us!) owes patients moreBY CINDI LEIVE  A PORTLAND PROTESTOR SAYS IT ALL ON JUNE 24, 2022. (SOURCE: GETTY IMAGES) It’s been 181 long days since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. And every morning, you probably pick up your phone to learn a horrific new consequence of that decision: bleeding patients turned away from hospitals, pregnant people prosecuted, doctors told by lawyers that they cannot do their jobs. Abortion is everywhere now. Not the procedure—that’s been around for 4,000 years—but the subject, which has re-entered public discussion after several decades of euphemisms and stigma. (All it took was an apocalypse.) As someone who worked through a lot of those silent, euphemistic years, I’m wowed daily by the commitment and resourcefulness of the journalists on this beat, along with the patients telling their own stories under the toughest circumstances. All of which has made me reflect on my own coverage of abortion—and how to do it better. A little personal history: When I first started in women's magazines in the 1990s, few major outlets covered abortion. (The publications of the 1980s had done so more openly—it was on the cover of People in 1985!—but by the ‘90s, the self-proclaimed “pro-life” movement had begun its ascent, and the assumption that abortion was distasteful and divisive settled in.) I was lucky enough to work for a boss who felt differently. When state legislatures began to pass bills requiring teenage girls to get permission from their parents—or a judge—in order to end a pregnancy, I walked into an editorial meeting, voice shaking, and pitched a story on the laws; she green-lit it—unusual at that time—and we went on to do a series that exposed the rising shortage of doctors willing to do abortions at all. Over the years that followed, I was proud of the stories the teams I led did—and generally confident that sharing the truths of what pregnant people experience would prompt progress to roll forward, and minds to change. By the time I got around to writing about my own abortion (emboldened by many who’d shouted before me), TRAP laws and doctor assassinations were putting more and more providers out of business; the Hyde amendment had made abortion difficult-to-impossible for low-income women. (All while Roe still stood!) But I still held out hope, on some level, that personal stories mattered. Wouldn’t it make a difference, I wrote, if the people who wanted to deny us our freedom had to look us in the eye?  PROTESTORS IN DETROIT, JUNE 24, 2022 (PHOTO BY EMILY ELCONIN/GETTY IMAGES) Well…maybe. Since then—and especially since Texas’s SB8 went into effect last fall—personal abortion stories have come fast and furious. On talk shows and the floor of Congress, in Sunday sermons and YouTube testimonials, in amicus briefs, and the set of SNL, people who’ve chosen abortion have shared their experiences with mounting urgency and the frustration that comes from feeling like no one cares. In the years that come, those stories are going to be especially important, and some will be devastating. But what do we (meaning the media, The Meteor included) owe the people who tell these stories? And now that everyone’s talking about abortion, how can we talk about it better than we used to?

TOTAL ACCURATE AND INACCURATE ABORTION-RELATED STATEMENTS PER CABLE NEWS NETWORK, AS OF FEBRUARY 8, 2019 (SOURCE: MEDIA MATTERS FOR AMERICA)

Finally, and most importantly: It’s not just about abortion. During my decade and a half as the editor of Glamour, we published plenty of abortion stories I was proud of—how it felt to have one, to self-manage one, to jump through legal hoops to get one. But in 2010, the GOP weaponized gerrymandering to rewrite the makeup of key legislatures; pretty sure we never covered it. In 2013, the Supreme Court green-lit voter suppression with its historically awful Shelby County v. Holder decision; again, we never covered it. Obviously, we should have—for a million reasons, but partly because the political machinery the right put in place over that decade laid the groundwork for our current abortion hellscape. Many of the trigger bans which snapped into cruel effect after Dobbs were in states like Ohio, Missouri, and Georgia, where the majority of people favor legal abortion, but ruthless gerrymandering or voter suppression meant it just didn’t matter. We were telling stories, but not the whole story. The story of abortion is fundamentally not just a story about bodily autonomy and why crusty white men should have any say about whatever’s in your uterus. (Although, let’s be clear, they should not.) It’s a story about why our country still accepts that presidents who lose the popular vote can nominate justices who are confirmed by a Senate which radically over-represents white, agrarian states and that those justices then can green-light laws passed by state governments which no longer represent the will of their people. It’s a story about misogyny, yes, but it’s also about the malapportionment of the Senate—even though those words are really hard to make appealing in a Good Morning America segment. (Only Stacey Abrams can do that).  STACEY ABRAMS SPEAKS ABOUT THE GEORGIA ABORTION BAN JULY 20, 2022 (SOURCE: GETTY IMAGES) A few days after Roe fell, I interviewed Dahlia Lithwick, and her words rang in my head for months. That very first week, "I had a pollster say to me, ‘Dahlia, women just don’t care about structural democracy reform," she said. "And my answer was kind of like, well, then prepare to keep losing, 'cause we can’t fix this with marching and tote bags." And she’s right: As Black women organizers have been saying for a century, voting rights underpin all other freedoms, and abortion is no exception. Though it may sound impossibly optimistic, I believe we are going to win on abortion, at least eventually and at least technically. There are too many of us, there will be too many horror stories, and the punishment for politicians, even in this messed-up democracy, is already evident. Securing reproductive freedom might take years and would be heroic. But if we only attend to abortion and not the larger landscape that permitted the laws against it to thrive—the same landscape that enables laws against LGBTQ populations, poor people, immigrants, and gun reform—we will be back, Whack-a-Mole style, to attend to the next issue, and the next, and the next.  Cindi Leive is the co-founder of The Meteor, the former editor-in-chief of Glamour and Self, and the author or producer of best-selling books including Together We Rise. Her related reading recommendation: This CJR piece; it's excellent.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

The Abortion Stories I Wish I'd Told

December 22, 2022FEATURED STORY

THE ABORTION STORIES I WISH I'D TOLD

Our personal experiences matter, but the media (including us!) owes patients more

BY CINDI LEIVE

It’s been 181 long days since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. And every morning, you probably pick up your phone to learn a horrific new consequence of that decision: bleeding patients turned away from hospitals, pregnant people prosecuted, doctors told by lawyers that they cannot do their jobs.

Abortion is everywhere now. Not the procedure—that’s been around for 4,000 years—but the subject, which has re-entered public discussion after several decades of euphemisms and stigma. (All it took was an apocalypse.) As someone who worked through a lot of those silent, euphemistic years, I’m wowed daily by the commitment and resourcefulness of the journalists on this beat, along with the patients telling their own stories under the toughest circumstances.

All of which has made me reflect on my own coverage of abortion—and how to do it better.

A little personal history: When I first started in women’s magazines in the 1990s, few major outlets covered abortion. (The publications of the 1980s had done so more openly—it was on the cover of People in 1985!—but by the ‘90s, the self-proclaimed “pro-life” movement had begun its ascent, and the assumption that abortion was distasteful and divisive settled in.) I was lucky enough to work for a boss who felt differently. When state legislatures began to pass bills requiring teenage girls to get permission from their parents—or a judge—in order to end a pregnancy, I walked into an editorial meeting, voice shaking, and pitched a story on the laws; she green-lit it—unusual at that time—and we went on to do a series that exposed the rising shortage of doctors willing to do abortions at all.

Over the years that followed, I was proud of the stories the teams I led did—and generally confident that sharing the truths of what pregnant people experience would prompt progress to roll forward, and minds to change. By the time I got around to writing about my own abortion (emboldened by many who’d shouted before me), TRAP laws and doctor assassinations were putting more and more providers out of business; the Hyde amendment had made abortion difficult-to-impossible for low-income women. (All while Roe still stood!) But I still held out hope, on some level, that personal stories mattered. Wouldn’t it make a difference, I wrote, if the people who wanted to deny us our freedom had to look us in the eye?

Well…maybe. Since then—and especially since Texas’s SB8 went into effect last fall—personal abortion stories have come fast and furious. On talk shows and the floor of Congress, in Sunday sermons and YouTube testimonials, in amicus briefs, and the set of SNL, people who’ve chosen abortion have shared their experiences with mounting urgency and the frustration that comes from feeling like no one cares.

In the years that come, those stories are going to be especially important, and some will be devastating. But what do we (meaning the media, The Meteor included) owe the people who tell these stories? And now that everyone’s talking about abortion, how can we talk about it better than we used to?

-

First of all, keep talking. Remember that era of silence on abortion? The silence, it turns out, was mostly on the left: One study of cable news coverage during the ’10s found that 94% of all abortion mentions were on Fox. Eighty-five percent of those were filled with lies—about abortion’s risks or what Planned Parenthood does all day—but at least among major news outlets, they went unchallenged. In other words: Even if it feels like we’ve talked enough—we haven’t. And if we stop, they’ll fill the void.

-

Oh, and talk to the right people. Abortion is health care. But one reason we don’t always see it that way is that the media doesn’t. A 2020 NARAL study found that while 65% of news stories about abortion quoted a politician, only 14% quoted a medical professional—and only 8% quoted an actual human person who’d had an abortion! (Even more enragingly, the NIH found that language personifying the fetus turned up twice as often as any story about a woman.) In the years to come, providers and patients will be closest to the pain, and they should be the loudest voices. As Renee Bracey Sherman says, borrowing a quote from the disability rights movement: “Nothing about us without us.”

-

And remember who “us” is. Even in 2022, a year where you were more likely than ever to see a TV character making an abortion decision, the majority of those characters were white, wealthy, and not parenting a child, according to a new report from Abortion Onscreen. In reality, the majority of people who seek abortions are BIPOC, have at least one child, and wrestle with the financial realities of care. (Abortion pills—now used in the majority of American abortions—are also weirdly absent.) Portraying abortion frequently is good; portraying it frequently and accurately is better.

-

Speaking of accuracy: No more using anti-abortion terms as if they are fact. The misnomer “pro-life” is, at long last, being phased out of news coverage. (I wish I could erase it from old headlines I edited.) But right-wing-manufactured terms like “heartbeat bill” and “fetal pain”—or the habit of calling the pregnant person the “mother,” as Andrea Grimes has reported—still pop up in mainstream outlets even though they have no basis in science. Let’s use a better, fairer dictionary.

Finally, and most importantly: It’s not just about abortion. During my decade and a half as the editor of Glamour, we published plenty of abortion stories I was proud of—how it felt to have one, to self-manage one, to jump through legal hoops to get one. But in 2010, the GOP weaponized gerrymandering to rewrite the makeup of key legislatures; pretty sure we never covered it. In 2013, the Supreme Court green-lit voter suppression with its historically awful Shelby County v. Holder decision; again, we never covered it.

Obviously, we should have—for a million reasons, but partly because the political machinery the right put in place over that decade laid the groundwork for our current abortion hellscape. Many of the trigger bans which snapped into cruel effect after Dobbs were in states like Ohio, Missouri, and Georgia, where the majority of people favor legal abortion, but ruthless gerrymandering or voter suppression meant it just didn’t matter.

We were telling stories, but not the whole story.

The story of abortion is fundamentally not just a story about bodily autonomy and why crusty white men should have any say about whatever’s in your uterus. (Although, let’s be clear, they should not.) It’s a story about why our country still accepts that presidents who lose the popular vote can nominate justices who are confirmed by a Senate which radically over-represents white, agrarian states and that those justices then can green-light laws passed by state governments which no longer represent the will of their people. It’s a story about misogyny, yes, but it’s also about the malapportionment of the Senate—even though those words are really hard to make appealing in a Good Morning America segment. (Only Stacey Abrams can do that).

A few days after Roe fell, I interviewed Dahlia Lithwick, and her words rang in my head for months. That very first week, “I had a pollster say to me, ‘Dahlia, women just don’t care about structural democracy reform,” she said. “And my answer was kind of like, well, then prepare to keep losing, ’cause we can’t fix this with marching and tote bags.” And she’s right: As Black women organizers have been saying for a century, voting rights underpin all other freedoms, and abortion is no exception.

Though it may sound impossibly optimistic, I believe we are going to win on abortion, at least eventually and at least technically. There are too many of us, there will be too many horror stories, and the punishment for politicians, even in this messed-up democracy, is already evident. Securing reproductive freedom might take years and would be heroic. But if we only attend to abortion and not the larger landscape that permitted the laws against it to thrive—the same landscape that enables laws against LGBTQ populations, poor people, immigrants, and gun reform—we will be back, Whack-a-Mole style, to attend to the next issue, and the next, and the next.

"They Chose to Make History."

"THEY CHOSE TO MAKE HISTORY"

For Iranian American journalist Neda Semnani, 2022 belongs to the women and girls of Iran.

BY NEDA TOLOUI-SEMNANI

December 20, 2022

Mahsa ‘Jina’ Amini, a Kurdish-Iranian woman, was on her way to the rest of her life when she was profiled, detained, and allegedly beaten to death in Tehran, Iran in September.

Amini’s fate, like so many other women’s, was decided in a split second by a man who looked at her and saw only what he wanted to see: her hijab askew. Both she and he knew that the systems and institutions of the country were created to benefit one of them over the other.

Perhaps if Amini had died at another moment in time, no one but her family would have known her story. But on this particular day, the young women and girls of Iran decided to reclaim her agency and their own.

They chose to make history.

They flooded the streets and social media en masse to mourn Amini—but not only Amini. They mourned all the others who had died, who were imprisoned, who were held down by hopelessness. Iran’s women wept in public, many pulling off their state-sanctioned hijabs and cutting off their hair. And they weren’t alone. Every other marginalized group in the country joined them: Kurds and Baluchs, Black and queer, Ba’hai and Jewish, and so many others. Each person demanding equal rights for women. Each person taking up space and screaming for their history—our history—to be acknowledged, to be heard, to be integrated into the story of their country and the world at large.

As an Iranian American and a journalist, I have watched all of this from the safety of my New York apartment. Never have I felt as connected to my ancestral homeland and its people as I have during these long weeks, and never have I felt the distance between us so acutely.

Since the uprising began, Iranians—women, men, and non-binary people—have burned their hijabs and the Iranian flag; they’ve come together in public; they’ve made music and theater, harnessed spray paint and brushes; they’ve danced and kissed in the streets. Each nonviolent action like a ballistic missile aimed at the core of the ruthless regime and its sophisticated surveillance state.

And after the women and girls of Iran decided to stand together, the men who rule the country fell apart. They began clutching at power through blunt force and unimaginable brutality. Since September, the Islamic Republic has killed more than 500 people, including at least 57 children, and arrested more than 1800. They have made freedom fighters of school girls and martyrs of teenagers. They’ve rounded up and jailed more than 58 journalists, most of whom are women. They’ve set fire to a prison which was filled past capacity with dissidents. They’ve used buckshot to shoot at women’s faces and genitals; hundreds of protestors have lost their eyesight. The security forces have used ambulances to pick up demonstrators and monitored hospitals to find those who had gotten away. They’ve raped and sexually assaulted protesters, many of whom are in their teens and early 20s. Security forces have allegedly tried to stop people from witnessing atrocities by shooting into homes where people were looking out of their windows.

Then last month, the parliament went further. It voted to make protest punishable by death, dissolving whatever trust was left in the Islamic Republic and officially pitting the government against its people.

Sham trials followed. Last week, in the city of Mashhad, cranes were erected, stretching high into the air. Steel trees bearing strange fruit: two young men dead, their bodies hanging above the heads of the people.

Their names are Mohsen Shekari and Majidreza Rahnavard. They may have been the first and second official execution, but they are not the first or second to die at the hands of the Islamic Republic.

The point of these killings isn’t to punish individuals or to protect the regime or warn off protesters; it is an attempt to obliterate hope. Yet they can’t extinguish what doesn’t exist. Because the simple truth is that as long as this regime is in power, the people say there is no hope in their future; their hope will be reborn when this regime is gone. So the revolution marches on and the people chant, “Thousands stand behind each one killed.” In other words: “You can’t kill us all.”

***

This Iranian uprising, this revolution, keeps falling in and out of the headlines, a fact that belies its global importance. Iran at this moment contains the intersection of so many issues: economics, foreign policy, technology, health, religion, sectarianism, race, and class—underpinned, at least for now, by feminist values. It is like nothing we’ve seen before, making it arguably the most important story in the world, the most important story of our time.

We’re watching one generation rise up where others have cowered. We’re watching the people come together to champion the rights of women. We’re watching them reach for democratic values and ideals, not with resources or institutional support, but with their weapons of choice: speech, assembly, art, music, literature, poetry, fashion, and movement.

As an Iranian, an American, and a woman, I’m devastated that for many outside Iran, this moment is, at most, a hashtag and a chance for people to push their political agendas. Women, minorities, and their allies are being attacked by their government and fighting for their very survival. It isn’t on the front page of every country’s newspapers, but it should be.

So what can we do, you and I, to show up and engage with this moment? We have to support these women, children, men, boys, and non-binary Iranians by going out of our way to report their stories and amplify their voices. As we see more Iranians flee their country, we must open our own borders and provide refuge.

Finally, we must acknowledge that in order for this revolution to succeed, many brilliant, beautiful, and brave human beings will give up their futures for someone else’s. We must acknowledge their suffering, their fears, and most of all, the lives they won’t get to live. We must also acknowledge the people they leave behind and the pain those who will survive will carry with them. This is what it means to resist and to revolt. It means that one group will sacrifice their plans, their potential, and all their normal mornings so that perhaps, one day soon, the rest of us might revel in freedom.

Neda Toloui-Semnani is an Emmy-winning journalist and the author of They Said They Wanted Revolution: A Memoir of My Parents.

Photo by Nilo Tabrizy