To No One's Surprise, Millennials Aren't Looking Forward to Motherhood

A home for modern feminism

If only there was something we could do about that…

By Shannon Melero

Around this time last year, I was waddling around my baby shower, taking pictures, and picking food off people’s plates (pregnant privilege) when a friend of a friend came up to me and whispered, “I hated my baby shower, too. But at least it’s almost over.”

I gave a non-committal smile and pretended I had to use the bathroom. Exchanges like this were a regular occurrence throughout my pregnancy; everyone I talked to projected their own experiences onto mine. Never mind the fact that I actually loved my shower and happily ruined my elaborately secured headpiece by doing the dutty wine in the middle of the dance floor, belly and all—my pregnant body was just a placeholder for the feelings of others that they now felt comfortable voicing.

And what struck me is that so many of those feelings were negative. Horror stories about all of the bad things that would happen to me before, during, and after childbirth. It seemed like not a soul had anything positive to say about motherhood.

It turns out this doom-and-gloom narrative surrounding all things mommy is unique to millennials, as Rachel M. Cohen laid out last week at Vox in the now-viral “How Millennials Learned to Dread Motherhood.” Cohen dissects the many, many ways non-moms have been conditioned to think about motherhood:

“College-educated millennial women considering motherhood — and a growing number from Gen Z too — are now so well-versed in the statistics of modern maternal inequity that we can recite them as if we’d already experienced them ourselves. We can speak authoritatively about the burden of “the mental load” in heterosexual relationships, the chilling costs of child care, the staggering maternal mortality rates for Black women. We can tell you that women spend twice as much time as men on average doing household chores after kids enter the picture, that marriages with kids tend to suffer. We’re so informed, frankly, that we find ourselves feeling less like empowered adults than like grimacing fortune-tellers peering into a crystal ball.”

Add to this the absolute barrage of mommy content that Cohen details, from self-help parenting books to idyllic momfluencers warning millennials about the highs and mostly lows of having a child—and it makes sense that the birth rate in the U.S. is on the decline.

Cohen’s overall thesis wasn’t that millennials hate kids, but that we are being inundated with so much negative information about motherhood that it’s practically in the air we breathe. And she’s right. If I didn’t already have a kid myself and was going off what I read, I’d think it was the worst possible choice I could make in life.

But what I find frustrating about the mountains of think pieces around motherhood is how much time is devoted to the over-intellectualizing of The Decision and its pitfalls rather than mothering itself. It’s the navel-gazing on who-what-when-where-and-why people are deciding to have kids that distracts us from the larger issue: addressing the massive structural hurdles that have been placed in front of mothers for decades.

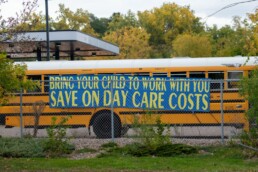

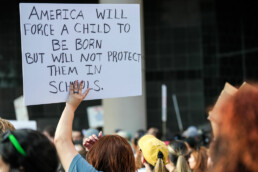

Consider the lack of affordable childcare, soaring costs of food, diaper shortages, and crumbling social safety nets for children in America. Add to that the absence of post-partum care, unless you pay for it out of pocket—the decision to skip motherhood is practically made for you. But all this constant talk about how hard motherhood can be isn’t giving way to what we as a society can actually do about it. Part of the structural problem is America has such an individualistic culture that we don’t think other people’s children are our problem. Whereas, for example, many Latine cultures emphasize the “village” approach to raising children. (Cohen also gets into how politicians, particularly Republicans, actually weaponized family-first values in such a way that made progressive millennials feel they were falling into a GOP trap if they voiced wanting a family.)

Once I gave birth to the world’s cutest baby (this has been fact-checked), people were notably less interested in having theoretical discussions about my decision to have a child. In their minds, by going through with that choice, I’d already done the hard part; I’d signed up for my miserable mommy fate and must endure it on my own. All that intellectualizing about why I would want to have a baby only to have my experience as a mom, like many other moms, boiled down to internet memes about sleeplessness and clueless partners. It is incredible how moms are so seen and discussed as theoretical figures, but in practice, we are invisible, obscured by our very own creation.

Now that I am a mom, I’ve been asked if motherhood is “worth it.” To that, I can only respond: Worth what? What thing do I hold up as a measuring stick to the experience of being a mom to determine its worth? There’s nothing that comes close, nothing that can really quantify the feeling I get when my kid laughs her screechy laugh. It’s also an incredibly insidious question because what we’re really asking moms is: Is your child’s life worth the money and resources that you’re demanding from the government?

That we spend so much time parsing and studying and surveying why people do or don’t want to have kids would be helpful if it actually went a step further and informed policy. Millennial mom-dread can be an interesting talking point we argue over for the next decade…or we can finally stop asking how to improve mom’s lives and just do the damn thing.

Shannon Melero-Urena

Shannon Melero is a Bronx-born writer on a mission to establish borough supremacy. She covers pop culture, religion, and sports as one of feminism's final frontiers.

32,000 more births

November 30, 2023NEWS,NEWSLETTER

November 30, 2023 Darling Meteor readers, Exciting news! If you click the button below, you’ll get your first annual Meteor Wrapped highlighting how much time you spent reading, what you clicked, and which Meteor events were your favorite. Just kidding! We don’t jive with creepy algorithms that put all your business out there (as entertaining as it is to see what everyone’s been listening to). In today’s newsletter, we check in with the abortion lawsuit in Texas, see dead things come back to life, and share our long reads for the weekend. Don’t need a Wrapped to know I only listened to Taylor, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON32,000 more births: On Tuesday, the Texas Supreme Court heard testimony from some of the 22 plaintiffs in a lawsuit arguing that the medical exceptions in Texas’s abortion ban are too narrow to protect women with complicated or nonviable pregnancies. The testimonies, from women whose lives were threatened by the denial of an abortion, ranged from horrific to unspeakable: last-minute travel plans after heartbreaking ultrasounds; sepsis; purple limbs from severe blood clots; and giving birth to a fetus missing parts of its skull. Writer Jessica Valenti pointed out on Xwitter that when asked by a judge if acrania (the condition that prevents the skull from fully forming) qualifies as an exception to the state’s abortion ban, the lawyer representing Texas admitted she didn’t know what it was. Yet another reason why non-doctors shouldn’t have final say over medical decisions. While some of the lawsuit’s plaintiffs were eventually able to obtain abortions, a new data analysis from the Institute of Labor and Economics sheds light on pregnant people who weren’t. The data estimates that a “significant minority”—between one-fifth and one-fourth—of women living in ban states who may have otherwise gotten an abortion did not get one. That means that in the first six months of this year, 32,000 more people than were expected based on past trends gave birth in those states. One of the authors of the paper says this reflects an “inequality story”: Women in their 20s and Black and Latine women—all of whom tend to be lower-income and are less likely to have the resources to travel—were disproportionately among those who gave birth. Ultimately, this study paints a far broader picture of who is affected by abortion bans than the Texas lawsuit is able to. The stories from the Texas plaintiffs—most of whom are white, married, and wanted to be pregnant before they were faced with medical emergencies—are terrible and dehumanizing, and demand justice. But if you widen the lens, you find a number of invisible victims, who may or may not fit the “good victim” stereotype. People of color are most affected by bans like the one in Texas (where the population is 40% Latine) and yet they remain underrepresented. Perhaps some of those 32,000 pregnant people were also diagnosed with fetal abnormalities—but the rest of them likely would have sought abortions for all kinds of individual reasons. Those reasons don’t matter. The right to bodily autonomy is not conditional; we have to be in it for every last person. AND:

JUST CLICK THE LINK ABOVE TO GET YOUR UNIQUE SHARE CODE TO SEND TO FRIENDS. IF FIVE OF THEM SIGN UP, WE'LL SEND YOU A METEOR TOTE! ALREADY HAVE A CODE BUT CAN'T FIND IT? NO WORRIES, IT'S WAITING FOR YOU DOWN BELOW. ⬇️

WEEKEND READING 📚

Correction: An earlier version of this piece stated that the students in Vermont had been killed instead of injured. We regret the error.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their unique share code or snag your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

Who gets to be called "child"

November 28, 2023NEWS,NEWSLETTER

November 28, 2023 Salutations, Meteor readers, If you’re reading this, it’s time to toss out your Thanksgiving leftovers. I’m sure it all still tastes great, but is five-day-old potato salad really worth the risk to your gut health? In today’s newsletter, we look at the media’s coverage of the temporary truce in Gaza, a staggering report out of Puerto Rico, and as much good news as we can muster. Clearing the fridge, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONWar of Words: What do you call a 13-year-old taken from their home and held against their will by an armed group? Well, it depends. After more than a month of siege warfare, a humanitarian pause was established between Hamas and the Israeli government. As part of this pause, each group agreed to an exchange of hostages and transport of aid into Gaza, the first positive thing that’s happened in weeks. While Israeli children have been accurately described as “child hostages,” Palestinian children captured by the IDF and held for years without trial are being referred to as “detainees,” “minors,” or “prisoners under the age of 18,” which is a lot of words to avoid saying “children.” (Keep in mind that many of the people Israel released have not been tried or convicted of any crimes and include teenagers who were arrested years ago without formal charges.) As the Gazan activist Bisan asked in a social media post last week, “Are our children less children than theirs?”  A 17-YEAR-OLD RELEASED FROM ISRAELI JAIL REUNITES WITH HIS FAMILY. (PHOTO BY SAEED QAQ/ANADOLU VIA GETTY IMAGES) The choice to use such varying descriptors for children is not unique to the current news cycle. We can see it in the way Black boys routinely face “adultification” in the media: Michael Brown wasn’t just a teenager shot by a cop; he was “no angel.” Children captured at the U.S. southern borders aren’t innocents held and transported against their will; they’re “detained migrant minors.” White children and teens, on the other hand, are often described in terms that elevate their youth and victimhood—sometimes even if they’re the ones committing the crimes. They’re not terrorists; they’re troubled; they’re mentally ill; they’re “volunteers.” It should not need saying: Both Israeli and Palestinian children are victims of horrific violence. No child asks to be born in an oppressed territory or to live under an oppressive government. And all children deserve accurate, thoughtful, and fair reporting from our news institutions. As James Baldwin famously wrote in The Nation in 1980: "The children are always ours, every single one of them, all over the globe; and I am beginning to suspect that whoever is incapable of recognizing this may be incapable of morality." AND:

TELL ME SOMETHIN’ GOOD

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

The Evolution of Momfluencing

A home for modern feminism

Reflections on the “mamasphere,” 15 years in

BY KATHRYN JEZER-MORTON

I recently went to the theater to see Killers of the Flower Moon, a story of genocidal greed set in Osage County, OK. Its lengthy runtime gave me ample opportunity to think about The Pioneer Woman, one of the internet’s original superstar mommybloggers. A dozen years before Martin Scorsese’s film, Ree Drummond, aka the titular Pioneer Woman, had been responsible for putting her small town of Pawhuska, OK on the pop cultural map.

I haven’t read Drummond’s writing in years. But around 2007, in the early days of mommyblogging, I read everything she wrote, and I wasn’t even a parent yet. She was irresistible—zany and folksy, and her recipes came out well. (I never understood coffee cake until I made this one, the best I’ve ever had.) She took great pictures before most bloggers had the tools to do that. She let you into her home in a way that felt both sincere and idealized—an elusive quality that sat lightly between “unfiltered” and “fake.”

But 16 years later, momfluencing looks nothing like what Ree Drummond helped create. For her part, she’s outsourced almost all the writing on her site, where she’s now eerily referred to in the third person. She runs a massive lifestyle empire that spans national retail, television, and businesses she runs in Pawhuska. She has realized a common dream among content creators: to leverage online fame into tangible sustenance.

The “mamasphere,” as those of us who study this space call it, has dramatically evolved in the past decade, reflecting changes not just in how we consume content, but in how we understand what motherhood is. Momfluencers used to propose a fantasy of domestic harmony, but even for juggernauts of the genre like Ree Drummond, the real world has found its way into the space, and it’s made representing the cute and cozy moments of family life more complex than it used to be. First of all, real life has intervened: early bloggers like Natalie Jean of Nat the Fat Rat and Jill Smokler of Scary Mommy have since left the space due to burnout and personal turmoil. Heather Armstrong, one of the first great talents to emerge from mommyblogging, openly struggled with depression and took her own life earlier this year.

Meanwhile, audiences have gotten bored of picture-perfect content. We expect something very hard to pull off: compelling storytelling about real-life struggles that’s presented beautifully, by someone who could be our friend. Since I began my doctoral research in 2017 about how momfluencers create easily consumable family stories, the mamasphere has fragmented into myriad niches: tradwives, Christian quiverfull families, crunchy moms, neoliberal supermoms, fashion moms, proudly basic goofy moms, mental health advocate moms, party moms, and mom-humor meme accounts. Despite TikTok’s massive influence, Instagram remains the power platform for momfluencers, whiteness remains the dominant racial regime, and hetero remains the default sexuality.

Of all the niches, the freshest and most compelling are the momfluencers who create meta-commentary about momfluencing itself—a phenomenon that could only exist in a genre that has reached a certain level of historical maturity. Jane Williamson is a standout, using physical comedy to send up the tightly wound world of Mormon moms from Utah. She satirizes the rabid urge to execute the perfect fall decor and feuds with “Jessica,” a fictional fellow mom and nemesis.

There’s also Ceci Kane, who makes TikTok parodies of Facebook mom groups, critiquing the profoundly dysfunctional social environments that arise when isolation, anxiety, and boredom converge in online spaces. Lex Delarosa posts scenes of life as a “traditional” homemaker, without any of the elbow grease and struggle that have defined homemaking for most of history. Her videos are mostly straightfaced and unsettling, but occasionally she lapses into arch humor, leaving her audience laughing in bewilderment. In response to a video of her hand-churning butter in her kitchen, someone commented, “Ma’am, this Stepford satire be (chef’s kiss).” No one knows for sure whether Delarosa is a troll, or just someone with a blistering streak of self-awareness—which makes her all the more fascinating as an online persona.

Meanwhile, the archetypal Wine Mom, a relic of a pre-pandemic, pre-Trump world where jokes about moms and alcohol landed as somehow both transgressive and wholesome, has faded into the margins. According to Tara Clark, the creator of motherhood humor account @modernmomprobs, that kind of humor represents the past, as does what she calls “inept husband humor.”

“People don’t even touch that anymore, since the pandemic, when we began really talking a lot more about the invisible load of motherhood,” she says. “It’s just not funny anymore.” Wine moms have fallen out of fashion because of the popularity of sobriety, and the pandemic’s influence on conversations about addiction. Joking about mothers drinking wine or clueless husbands doing everything wrong once felt defiant and important, but now it just seems redundant and, at worst, sad.

The pandemic unseated aspirational content as the pinnacle of momfluencer discourse, and altered the tone of the mamasphere permanently. What has replaced it as a reliable source of engagement is what many creators call “vulnerable content.”

Jessica Turner has been a full-time content creator for two years. She’s an expert in earning income from affiliate links; her original content was upbeat and vanilla, featuring deals on clothing and household goods offered by major brands like Target and Walmart. But during the pandemic, her husband came out as gay and her marriage ended, and buoyed by the shift in tone that was legible across the mamasphere, she shared her story. “We needed to boldly be honest with ourselves,” she wrote on “the shortest and darkest day of the year,” the winter solstice. “A mixed-orientation marriage could not work.”

Turner’s audience broke the hallowed 100k mark during that time, in part thanks to her willingness to be open about her marriage’s evolution. “Certainly if you want to get into metrics, I’ve found that those types of vulnerable, honest posts, whether it’s the grief of my marriage ending, or navigating dating, or exploring my own worthiness – those posts tend to do really well,” she said. “It stops someone’s scroll, to see vulnerability and authenticity.” (She’s since lost some followers, after posting about supporting gun control after a school shooting in Nashville.)

There’s a financial incentive to all that soul-baring. Back in the early 2010s, when Ree Drummond had me and my fellow office-bound young women in a chokehold with her accounts of cooking lunch for her ranch hands, it seemed like momfluencing was a gig that any cheerful mom with a camera could make a go of. But like every unregulated industry, it’s gotten harder to make a living at it. While her income from affiliate linking and other brand partnerships is higher than it’s ever been (in the mid six-figures) Turner admits that it takes serious expertise and focus to earn a living as a momfluencer today. “You have to be a savvy business person for it to be lucrative, or you have to have a massive, massive platform.”

As the barrier to entry rises, and the demands on one’s willingness to disclose sensitive details become relentless, it’s worth asking: Who will opt into this hustle, under these terms? So far it appears to be a new generation of content creators that are primed for competition, strategy, and shape-shifting, rather than wholesome family storytelling.

The work of motherhood itself probably hasn’t changed much in the last 15 years, but the cultural conversation about it has become unrecognizable. The labor of it, and the reality of what our society requires of mothers, can no longer be easily concealed from view without becoming a potent political symbol. We aren’t satisfied with fantasies; we want to see “real life,” only idealized. We expect to be entertained while also feeling seen; we want momfluencers to be better-groomed versions of ourselves.

It’s a lot to ask of a random stranger. All we expected from Ree Drummond in 2010 was to take step-by-step pictures of her recipes and crack jokes about her love of butter. Nowadays, Drummond would need to double-down on being “trad,” or disclose more suffering, or perhaps simply have a larger family. As an audience, we have grown accustomed to a nearly impossible standard. And young momfluencers have no choice but to keep up.

Kathryn Jezer-Morton is a writer in Montreal. She writes Brooding, a biweekly newsletter about contemporary family life, for The Cut.

Kathryn Jezer-Morton is a writer in Montreal. She writes Brooding, a biweekly newsletter about contemporary family life, for The Cut.

The women keeping femicide on the front page

|

No images? Click here Darling Meteor readers, A group of Swifties in Brazil, where Taylor Swift is scheduled to perform on the next leg of the never-ending Eras tour, wants to project her “Junior Jewels” t-shirt onto Rio de Janeiro’s Christ the Redeemer statue. If I were a Christian, I would absolutely jump at this opportunity to have Taylor Swift put Jesus on the map. I mean if she can do it for the NFL…  In today’s newsletter, Mariane Pearl writes about the network of citizen journalists tracking the staggering number of femicides across the globe. Plus more news out of Ohio, a very strange blast from the past, and a special Red Cup Day “celebration.” Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON

Femicide on the Front PageMeet the global network of activists and citizen journalists determined to document violenceBY MARIANE PEARL PORTRAIT OF ACTIVIST AND RESEARCHER HELENA SUÁREZ VAL. (IMAGE BY SOLEDAD MORAGA) On a sunny, crisp, fall weekend, Dawn Wilcox sits in front of a computer in her suburban Dallas home with her cat perched on her lap, building her database. She scours news reports and police records for details about Ashli Ehrhardt Wonder, a 29-year-old woman allegedly killed by her estranged husband in Kansas City, Missouri, on September 22, 2023. The details are horrific, down to the fact that the assailant wrote his last name in blood on Wonder's leg. Wilcox, 60, marks Wonder as the 729th known femicide in the United States this year. A couple rows below, #731 is 26-year-old tech founder Pava LaPere, a beloved Baltimore CEO who was named in Forbes’ 30 Under 30 list earlier this year. A man followed her home and strangled her in late September. And LePere and Wonder were far from alone; femicide—the killing of women and girls because of their gender— increased by 24% in the U.S. between 2014 and 2020, according to a 2022 report by the Violence Policy Center. In the United States, often “people think femicide only occurs in Afghanistan and other so-called ‘developing’ countries, but this is happening right here on an unimaginable level,” Wilcox says. “Each death isn’t a cold number or a statistic, but a human being…a woman with hopes and dreams.” A few hundred miles away, north of Little Rock, Arkansas, 52-year-old Rosalind Page is adding an entry to her own grim database. On October 3, Sian Cartagena, an 18-year-old woman whose mother described her as “victim to a domestic abusive relationship” died two days after being shot in Allentown, Pennsylvania. “At least five Black women and girls are killed each day in the U.S.,” says Page, noting that Black women are disproportionately impacted by intimate partner violence and femicide. “This is an epidemic and it’s only getting worse.” Wilcox and Page aren’t professional journalists. They’re both full-time nurses who, driven by passion and frustration, have become investigative reporters in their spare time. Wilcox, a domestic violence survivor, has spent the last seven years building Women Count USA: Femicide Accountability Project, a database that has recorded 12,500 women murdered since 1950. Page, who has spent the last three decades working at a hospital, launched her database, The Black Femicide Prevention Coalition, after she noticed a pattern: More than half of the Black women she treated were victims of male-perpetrated violence. Wilcox and Page are part of an unlinked but growing global army of activists and journalists, from Uruguay to Algeria, who are taking it upon themselves to track femicide, one of the most extreme forms of gender-based violence. Exasperated by what they see as government inaction and inadequate media coverage, they are committed to honoring victims, pushing the news industry to do better, and providing the kind of vital data that can actually catalyze change. “We’re doing this work hoping that it becomes obsolete,” said Helena Suárez Val, who in 2014 started Feminicidio Uruguay, a public database tracking femicide in her country, where gender-based violence is the second most reported crime behind theft. Val has since collaborated with similar women-led data efforts throughout South America through a collective she co-founded called Data Against Femicide. As she describes it: “Our data is our activism…one of the tools that will hopefully bring down the misogynist master’s house.” This series is a collaboration between the Gender, Ethic, and Racial Justice - International program at the Ford Foundation and The Meteor.  MEET US AT THE THEATERWe are thrilled to announce that In Love and Struggle Vol. 3: The Future is Around Us will be live at the Minetta Lane Theatre in New York December 14-16. Come enjoy live performances from Cree Summer, Zainab Johnson, Mahogany L Browne, Amanda Seales, Nona Hendryx and more. Each night promises to be a magical experience with storytelling, music, and comedy.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their unique share code or snag your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Love, Actually is bad, actually

|

No images? Click here Dear Meteor readers, This past weekend, we had the pleasure of hosting our annual event, Meet the Moment, at the Brooklyn Museum. As we sit in the middle of global crises—regular attacks on our rights, rising antisemitism and Islamophobia, war and conflict—the whole idea of meeting the moment has never felt more crucial. Amidst all this grief, we focused on hope. As Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson said in conversation with Ilana Glazer, “I wake up every day and think, ‘How can I be useful?’… and pace myself with bad news, because it doesn’t change what I need to do.” A lesson to us all. In today’s newsletter, we offer a bit of that bad news, some not-so-bad news, and writer Scarlett Harris’s unsentimental thoughts about the 20th anniversary of Love, Actually. Ready to meet the moment with you, Samhita Mukhopadhyay  WHAT'S GOING ON

MORE ON “MEET THE MOMENT”At the intersection of advocacy, representation, culture, and politics, we heard from leaders like:  ALLIE PHILLIPS ADDRESSES THE CROWD (PHOTO BY MONNELLE BRITT)

12-YEAROLD SPORTS JOURNALIST PEPPER PERSLEY (PHOTO BY MONNELLE BRITT)

Our final conversation, between Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson and Ilana Glazer, brought a levity I’ve taken with me, including this tidbit:  ROM-COMS OF CHRISTMAS PASTLove, Actually is Bad, ActuallyTwentieth-anniversary thoughts about the much-memed rom-comBY SCARLETT HARRIS Love, Actually, which celebrated its twentieth anniversary this month, became a classic for its star-studded cast, British sentiment, and Christmas vibes. Over the years, it has inspired endless memes and spoofs. But the bloom has been off the rose for some time now. Sure, plenty of rom-coms don’t hold up when revisited in the stark light of the 2020s—the catfisher’s playbook You’ve Got Mail and the statutory-rapey Never Been Kissed come to mind—and even modern takes like Happiest Season, Sierra Burgess is a Loser, and Marry Me sometimes rely on lazy stereotypes and outdated tropes. Still, when it comes to gender roles and relationship dynamics, Love, Actually is in a cringeworthy class of its own.  The 2003 British anthology rom-com, directed by Richard Curtis, follows an assortment of lovelorn Brits making the worst relationship decisions imaginable. Everyone, take a deep breath: Harry (Alan Rickman) is cheating on his perfectly nice wife Karen (Emma Thompson) with his vampy assistant, Mia (Heike Makatsch). Mark (Andrew Lincoln) is in love with Juliet (Kiera Knightly), the new bride of his best friend Peter (Chiwetel Ejiofor, one of only two people of color in the entire cast). The recently-jilted Jamie (Colin Firth) falls in love with his Portuguese housekeeper Aurélia (Lúcia Moniz), with whom he can’t communicate due to their language barrier. And the Prime Minister (Hugh Grant) engages in sexual misconduct at his workplace when he pursues his young, naive aide, Natalie (Martine McCutcheon). This behavior looks saintly compared to his professional rival, the United States President (Billy Bob Thornton, doing his best Bill Clinton), who sexually assaults Natalie later in the movie. To quote the Black Eyed Peas: Where is the love? Many of these supposedly romantic scenarios occur in the workplace, but even if they don’t, little airtime is given to the power dynamics involved. Whoever decided it was dreamy for Mark to show up at Peter’s house to accost his wife with placards spelling out his true feelings was seriously disturbed. Ditto to Jamie proposing to a domestic worker he employs without ever having exchanged a word. The least problematic relationship could have been cold, rigid Harry cheating on long-suffering Karen were it not for Harry’s sketchy workplace romance. When the female characters aren’t getting fat-shamed, they’re being objectified. Most of their storylines center on how hot they are, or aren’t. Jamie falls for Aurelia based on physicality alone. There’s not much to Mia besides luring Harry to cheat through her feminine wiles. Since Mark spends the movie avoiding Juliet, one must conclude that he’s primarily drawn to her looks. The same goes for elementary school student Sam (Thomas Brodie-Sangster), who’s apparently had so little interaction with his crush that he’s surprised she knows his name. Sam’s stepfather, Daniel (Liam Neeson), is dating his own crush, played by thee Claudia Schiffer. (Why wouldn’t he be, when every over-50 and/or schlubby guy in Love, Actually gets the girl?) Laura Linney’s Sarah pining after Rodrigo Santoro’s Karl is one of the only connections that gives a woman agency and a sense of desire—though, it must be said, they’re still colleagues. The movie’s most egalitarian relationship is that of two body doubles filming a sex scene, John (Martin Freeman) and Judy (Joanna Page). I’m guessing their scenes are an excuse to incorporate some nudity and sex gags amidst a cast with the least sexual chemistry in rom-com history. Still, the actors’ meet-cute is surprisingly effective. Even while naked in front of the cameras, they talk to each other like respectful, normal human beings. If only the rest of the movie could have taken a cue from their dynamic. Watching Love, Actually now seems particularly jarring given the evolution of the romantic comedy over the last 20 years, both in its depiction of relationships and its stars. There’s still a long way to go, but rom-coms like Rye Lane; Red, White & Royal Blue; and Good Luck To You, Leo Grande are paving the way Love, Actually wishes it could have. If you’re itching for some simple Christmance spirit this year, throw on a Lifetime or Netflix movie instead of Love, Actually. It might be just as problematic, but at least it won’t be pretending to be something it’s not.  Scarlett Harris is a culture critic, author of A Diva Was a Female Version of a Wrestler: An Abbreviated Herstory of World Wrestling Entertainment, and editor of The Women Of Jenji Kohan.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their unique share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

When pregnancy is criminalized

|

Dear Meteor readers, We're coming to you today with a remarkable story. Lauren Smith is a mother of three in South Carolina now facing up to ten years in prison—for having smoked marijuana to alleviate her symptoms while pregnant with her youngest child. Smith's case sounds nightmarish, but it's not uncommon in post-Roe America, where fetal personhood laws have enabled prosecutors to more easily penalize pregnant people for their actions. Over the last five months, journalist Neda Toloui-Semnani has investigated this new legal environment, its implications, and Smith’s fight to keep her family together.  UNITED STATES OF ABORTION“I Didn’t Feel Like a Mother. I Felt Like a Criminal.”BY NEDA TOLOUI-SEMNANI GREENVILLE, SOUTH CAROLINA Lauren Smith thought she knew what to expect as she was rushed into the operating room. At 26, it was her third cesarean section. “I don’t remember much before or after because everything moved so fast,” she says. “I remember crying. I remember being cold and being wheeled in there, and then, laying back, and then, I remember looking at the clock. It was at an angle.” The surgeon cut her open and pulled out a squirming infant, a baby girl Smith would name Audrey. Delivered a month early, she was a strong, healthy, kicking-screaming, six-pound, five-ounce newborn. Smith thought she knew what would come next. But like a character in a Kafka tale, her world had shifted while she slept. The same day she delivered—February 18, 2019—a urine drug screen confirmed that she had used marijuana during her pregnancy. The next morning, Audrey’s meconium, the first stools voided by an infant, tested positive for THC, a compound found in marijuana. Three nights later, as Smith, who is Black, prepared to leave the hospital, a case worker and a lawyer from the Department of Social Services told her that because she had tested positive for THC, she could not take her new baby home. That’s when she started to scream. She was alone in the hospital room, the phone to her ear, sutures across her abdomen. She kept asking for someone—anyone—to explain what was happening. “I just remember nobody was there to speak for me,” Smith recalls. “I couldn’t even really speak for myself.” “I didn’t feel like a mother,” she says, “or a person who just had a baby. I didn’t feel like a victim. I felt like a criminal.” She said goodbye to her baby that night. Six months later, Smith would be arrested and charged with felony child neglect for using marijuana while she was pregnant with Audrey—a crime that, in South Carolina, carries a penalty of up to 10 years in prison. Through a complex sequence of events, the charge also led to her losing custody of her second child, Aiden, for two years. Smith’s trial has been pushed back again and again; as of publication, it is set for February 19, 2024.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

“I Didn't Feel Like a Mother. I Felt Like a Criminal.”

November 9, 2023FEATURED STORY

A home for modern feminism

All over the country, in the aftermath of Dobbs, pregnant people are being prosecuted for their behavior. This is the story of one woman, Lauren Smith, who’s facing a ten-year prison sentence—and fighting back.

By Neda Toloui-Semnani

GREENVILLE, SOUTH CAROLINA

Lauren Smith thought she knew what to expect as she was rushed into the operating room. At 26, it was her third cesarean section.

“I don’t remember much before or after because everything moved so fast,” she says. “I remember crying. I remember being cold and being wheeled in there, and then, laying back, and then, I remember looking at the clock. It was at an angle.” The surgeon cut her open and pulled out a squirming infant, a baby girl Smith would name Audrey. Delivered a month early, she was a strong, healthy, kicking-screaming, six-pound, five-ounce newborn.

Smith thought she knew what would come next. But like a character in a Kafka tale, her world had shifted while she slept.

The same day she delivered—February 18, 2019—a urine drug screen confirmed that she had used marijuana during her pregnancy. The next morning, Audrey’s meconium, the first stools voided by an infant, tested positive for THC, a compound found in marijuana.

Three nights later, as Smith, who is Black, prepared to leave the hospital, a case worker and a lawyer from the Department of Social Services told her that because she had tested positive for THC, she could not take her new baby home.

That’s when she started to scream.

She was alone in the hospital room, the phone to her ear, sutures across her abdomen. She kept asking for someone—anyone—to explain what was happening. “I just remember nobody was there to speak for me,” Smith recalls. “I couldn’t even really speak for myself.”

“I didn’t feel like a mother,” she says, “or a person who just had a baby. I didn’t feel like a victim. I felt like a criminal.” She said goodbye to her baby that night.

Six months later, Smith would be arrested and charged with felony child neglect for using marijuana while she was pregnant with Audrey—a crime that, in South Carolina, carries a penalty of up to 10 years in prison. Through a complex sequence of events, the charge also led to her losing custody of her second child, Aiden, for two years. Smith’s trial has been pushed back again and again; as of publication, it is set for February 19, 2024.

Smith is one of the hundreds of women in the U.S. who have been arrested—and, in many cases, had their children taken away—for behavior during their pregnancies, including the use of controlled substances both legal and illegal. These cases all hinge on fetal personhood, a legal precedent granting fetuses rights, often from the moment of conception.

In the year since the U.S. Supreme Court handed down Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which ended federal protection of abortion, at least 27 states have included fetal personhood language in their anti-abortion laws. But some states were taking action long before Dobbs, often by using “chemical endangerment statutes”—originally enacted to protect children—to prosecute women like Smith.

Smith’s story shows how the same governments breathlessly passing abortion bans are using related legal theories to police pregnancy—and how the same laws that purport to protect unborn life can destroy families in the process, leaving parents, grandparents, and caregivers to navigate the complex web of social service agencies, law enforcement officers, prosecutors, and medical staff alone.

“WHEN YOU MAKE PLANS, GOD LAUGHS”

Lauren Smith, 31, had big dreams. In high school, she was one of the top three runners on her track team in Deerfield, Illinois. But in her last season, she went in for a physical and learned that she was pregnant. At 16, she chose to have the baby.

Her second pregnancy, in her mid-twenties, was equally fraught; she spent much of it in a shelter for pregnant women in North Carolina. Smith used marijuana during both pregnancies.

After she gave birth to her son, Aiden, she moved to Greenville, South Carolina, to be closer to her mother, Toni, and her eldest daughter, Aniyah. Aniyah had chosen to live with Toni full-time years earlier, so now Smith hoped to reconnect with the child she had had so young.

In Greenville, she found a job waiting tables and planned to finish her G.E.D. and go to school to study nursing or maybe law. Then, she met a man and fell in love; they moved in together. Within a year, she was pregnant. They celebrated by going out for tacos.

“I had never really been excited for a pregnancy,” Smith says. “They’ve always been surrounded by turmoil and shame and just sadness, so to speak. So it was nice to share it with a partner. I was excited; I was happy.”

The couple thought of sweet ways to tell people their good news. For his mom, they gave her a gift: an ultrasound picture tucked into a tiny onesie.

“I had it all planned out,” Smith says. “‘I’m going to plan a baby shower, finally, for once. I’m going to be celebrated, and the baby’s going to be celebrated, and we’re going to get married.’ I just had all these plans and visions,” Smith says.

“They say when you make plans, God laughs.”

Over the course of her pregnancy, Smith’s relationship with her partner turned volatile. Their fights became increasingly intense, and then violent, according to Smith. Greenville’s Department of Social Services (D.S.S.) got involved when Smith was about six months pregnant after she ended up in the hospital with a severely dislocated shoulder. She spent a week in a domestic violence shelter with her 18-month-old son in tow. She says that the stress of D.S.S. scrutiny, an unstable relationship, and the physical demands of working in the service industry made a tough pregnancy even worse.

“It was morning sickness, afternoon sickness, night sickness,” she recalls. “It was miserable to the point where I would drink water, I would eat crackers, and it would just come up. There’d be times where I couldn’t even eat at all.” She was diagnosed with extreme nausea and vomiting, along with chronic dehydration and anemia. She had to go to the hospital to receive intravenous fluids and was advised to try to gain weight.

Smith’s mental health also suffered. She had prenatal depression and suicidal ideation, according to her medical charts. Her doctor prescribed Zoloft—which is safe during pregnancy—but it didn’t work for Smith. Her hair fell out while her anxiety and depression remained.

“I’M VERY OPEN WITH MY DOCTORS”

Whether or not Smith’s decision to self-medicate was safe is more a matter of opinion than indisputable science. The effects of marijuana on pregnancy and fetal or childhood development are uncertain. This is largely because it’s difficult to get Schedule I drugs—drugs the federal government claims have no medicinal value—approved for research and even harder to study their effects on pregnancy. “Most of our understanding is speculative and inferential,” says Peter Grinspoon, M.D., an instructor at Harvard Medical School and the author of Seeing Through the Smoke: A Cannabis Expert Untangles the Truth about Marijuana. (This August, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommended recategorizing marijuana as a Schedule III drug, which would shift it from being lumped in with heroin and cocaine and put it in the same category as drugs like ketamine and testosterone.)

What research does exist is limited and, at times, contradictory. A 2020 survey by the National Institute on Drug Use shows that there is “no human research connecting marijuana use with miscarriage,” and a 2019 Columbia University study went further, concluding that cannabis by itself will not harm a fetus or impede its development. However, other evidence shows that, in rare cases, cannabis use could result in low birth weight and abnormal fetal brain development. There is no research on what the threshold is for these risks or whether there is a safe or therapeutic amount of cannabis a person can ingest while pregnant.

“If I needed to roll a joint and hit it a few times to be able to still take care of my other children and work and live, that’s what I did.”

This dearth of research has led medical associations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Academy of Pediatrics, to recommend that patients abstain from using cannabinoid products while pregnant or breastfeeding.

At her second prenatal appointment, Smith told her OB-GYN that she was using marijuana medicinally. “I’m very open with my doctors,” she explains. “I feel like the only way they can help you is if you tell them everything. So I informed my doctor when they asked—I said I do smoke marijuana because it definitely helps with certain pregnancy symptoms that are hard to deal with.

“It wasn’t like I was doing bong rips or anything,” she says. “If I needed to roll a joint and hit it a few times to be able to still take care of my other children and work and live, that’s what I did. And I didn’t get any medical advice advising to steer away from it, or that it would cause any issues to the baby or to me, ever.” According to Smith, her doctor told her only that she should stop smoking marijuana 30 days before her due date to avoid a positive drug test.

Here, accounts of what happened differ. Smith’s medical chart states that someone “discussed the risks of [marijuana] use in pregnancy” with her, and both her medical chart and her social services files also note that she was advised to stop using cannabis and that a positive drug screen could have implications for her open social service case. Prisma Health, which owns both the clinic and the hospital where Smith was a patient, and the Department of Social Services did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

But Smith’s choice to self-medicate was not unusual: Marijuana is, in fact, the most common illicit drug used during pregnancy. A 2019 study by Kaiser Permanente Northern California found that more than seven percent of pregnant women reported using marijuana to treat depression, anxiety, stress, pain, and nausea, a jump from just four percent who reported doing so three years earlier. Young women were especially likely to have used marijuana during pregnancy—almost 1 in 5 of those ages 18 to 25 reported doing so. And race and economics are also a factor, with a higher percentage of Black, low-income women historically reporting cannabis use during pregnancy.

That makes sense to Amanda Williams, M.D, an obstetric-gynecologist, maternal care expert, and instructor at Stanford University’s School of Medicine. “When people have limited access to services,” she says, “then sometimes using something like THC to help manage their symptoms is a pathway that people choose to take. [There are] other means of managing depression and anxiety, like therapy, counseling, meditation, exercise—all of those things are possible. But if one doesn’t have access, especially someone with a psychosocially complex life, one can understand why they would seek other options.”

By the end of her seventh month, Smith says she had stopped using cannabis. On February 14, 2019, she arrived at the clinic for her OB-GYN appointment with her heart racing. The nurse took her vitals and told her that her blood pressure had spiked. At first, Smith thought it was because of stress: She had been fighting with her baby’s father on the way to the doctor’s office and had been experiencing preterm labor even while she worked long hours as a bartender, setting up and breaking down the bar. (“I have a high tolerance for pain,” she says.)

Now, at the clinic, the doctor was telling her she had extremely high blood pressure. She would be diagnosed with gestational hypertension. “If we don’t get this baby out,” Smith remembers the doctor saying, “you could die.”

What she says she did not realize was that that day, the medical center collected her urine for a drug screen. That drug panel, analyzed at Greenville Memorial Hospital’s lab, came back negative for everything except THC, the main psychoactive compound in cannabis.

The baby went through two rounds of drug testing. Her urine came back negative for all substances, so the hospital tested her meconium, which includes the remnants of materials ingested throughout the pregnancy. That test came back positive.

Marijuana testing is famously imprecise. Sources in both Greenville Memorial Hospital and Quest labs confirmed that the numerical results of THC tests simply show that Smith had used the drug at some point while pregnant but can’t reveal when the drug was ingested.

THE NEXT FRONTIER OF ANTI-ABORTION LAW

Fetal personhood laws have been a rallying cry for anti-abortion activism since long before the fall of Roe v. Wade.

Indeed, the legal theory was pioneered 26 years ago—in South Carolina, in fact—with the landmark 1997 Whitner v. State of South Carolina decision, which found that not only did a fetus have all the rights and privileges of a person under the age of 18, but that it was in the state’s best interest to protect them.

The case hinged on the experience of a woman from Easley, South Carolina, named Cornelia Whitner, a Black woman. In February 1992, she delivered her third child, a boy. Her urine and his came back positive for trace amounts of crack cocaine.

It was the time of the so-called War on Drugs, and South Carolina required hospitals to drug test every pregnant person at delivery—a law the U.S. Supreme Court would rule unconstitutional, but not until 2001, too late for Whitner. She was charged with felony child neglect and went on to serve eight years in prison.

Whitner appealed her conviction; a lower court overturned it, but then the state’s Supreme Court, in a three-man majority, ruled that a viable fetus had the same rights as a child and the conviction should be upheld. Fetal personhood had become legal precedent.

South Carolina’s then-Attorney General Charlie Cordon was the driving force behind the state’s argument. He had built his career prosecuting pregnant women who were struggling with addiction, and he also prosecuted health care workers, social workers, and drug counselors who didn’t report a mother’s drug use.

The effect of the court’s decision was immediate. In the year after the Whitner decision, The New York Times reported that 23 pregnant women who tested positive for crack cocaine in South Carolina had been charged with child neglect. Of those, 22 were Black. “I can’t help the fact that [crack cocaine] is the drug of choice for Blacks,” Cordon said at the time.

For the next decade, largely because of Cordon and Whitner, South Carolina led the country in pregnancy criminalization cases, according to a review of national data by Pregnancy Justice, a nonprofit that advocates for pregnant people caught in the criminal justice system. In hindsight, the Whitner decision and its legal champion Cordon were an early bellwether for where the anti-abortion movement is now. A new report from Pregnancy Justice found that between 2006 and 2022, as abortion protections began to atrophy across the country, cases of pregnancy criminalization tripled. Although they happened everywhere—in 46 states and territories—the vast majority can be traced to five states—Alabama, Tennessee, Oklahoma, and Mississippi, alongside South Carolina. In a few cases, women who experienced stillbirths and miscarriages were charged with homicide and jailed, but most cases, like Smith’s, involved women who were charged with felony child neglect or abuse after they or their infants tested positive for a controlled substance. Most of these cases were brought forward by medical and/or social service professionals, including doctors and case workers.

And since Dobbs, legislators around the country have been writing fetal personhood into law, making these cases easier to bring. Because of the legal concept of fetal personhood, “pregnant people have fewer rights than people who aren’t pregnant,” explains Trip Carpenter, a legal fellow with Pregnancy Justice. “If you are pregnant and you do something that allegedly puts your fetus or your pregnancy in harm, you could be charged with [a] crime.

“If you’re pregnant and you fall down the stairs, you could be charged with a crime,” he says. “If you’re pregnant and you drive without a seatbelt, you could be charged with a crime. If you’re pregnant and you have a glass of wine, or you use drugs, you could also be charged with a crime.”

And balancing the rights of a parent and a zygote or fetus isn’t straightforward, either. “Let’s look at extreme morning sickness,” says Robert Ianuario, a criminal defense attorney in Greenville who specializes in marijuana laws. “The mother can’t keep food down; the child’s not getting properly nurtured. If the mother smokes marijuana, doesn’t have the nausea, and can eat, then the child’s getting more nourishment. How do you balance that?”

Expanding fetal personhood has far-reaching implications. It could limit people’s ability to undergo IVF treatments or take needed prescription drugs. Also, as fetal personhood takes hold nationally, it falls to the discretion of individual prosecutors to decide which cases should be pursued to the full extent of the law and which ones should not. That level of discretion means that pregnant people are more vulnerable to criminal prosecution than ever before.

“Child neglect is a catchall to catch all of these people we consider throwaway people or people we don’t like,” says Carl Hart, PhD., one of the authors of the Columbia University study on cannabis and pregnancy and the author of the book Drug Use For Grown-Ups: Chasing Liberty in the Land of Fear. “You don’t have to say you don’t like them. You just put them under this category.”

A FAMILY TORN APART

Even after losing custody, Smith tried to breastfeed Audrey as she had her older children. For the first six weeks of Audrey’s life, she would wake up early—around 4 a.m.—and drive to the home of the paternal grandmother who has custody of Audrey to feed her daughter.

It was on one of these mornings in April, when Smith was holding Audrey, that Detective Robert Perry of the Greenville Sheriff’s Department called. Smith’s case had been referred to the police on March 21, 2019. She didn’t know she was under investigation. Perry recorded the call without her knowledge, a practice that is legal in South Carolina.

The Meteor acquired a copy of the recording and has reviewed it.

Perry asked if she had used marijuana recreationally, and she said no. She had been using it therapeutically and detailed her symptoms. “Well, that doesn’t sound like a wonderful trimester for you,” he said. “You poor thing.”

Perry acknowledged that the science is not clear about whether marijuana is harmful to the fetus or not.

“I’m not trying to give you a hard time,” he said, “but I’m also trying to be real plain with you, too. You could be facing criminal charges, and you might not be. A lot of parents, especially parents of kids are born with heroin or meth in their system, there’s no mercy for them. They get charged. Marijuana’s a little bit different.” As long as the parent cooperates, he explained, the state will work with them.

“I will touch base with you again,” he said, “I promise.” Smith never heard from him again.

Smith did not realize that on the basis of that phone call, a warrant would be issued for her arrest in May. It claimed that “the defendant placed her unborn child at risk of harm by exposing the child to marijuana while still in the womb. By exposing this child to this illegal drug, she affected the child’s life, health, and safety.” The charge: unlawful neglect of child or helpless person—a felony.

“Pregnant people have fewer rights than people who aren’t pregnant.”

Greenville’s Sheriff Department would not comment on the specifics of this case, but said that Detective Perry acted appropriately and within the law.

The police came for Lauren Smith on August 19, 2019. She remembers the sound of police cars screeching to a stop in front of the small townhouse—lights on, sirens blaring. She remembers officers and K-9 units—dogs—pounding up the short stoop, banging on the door. She remembers an officer swooping down to pick up her baby, who woke up screaming.

Initially, officers said they were there because Audrey’s paternal grandmother, who has custody of the child, thought there was a chance Smith would leave the state with the baby, which would have been considered custodial interference. Once Audrey was located, the paternal grandmother declined to press charges—but instead of leaving, officers executed the open warrant for marijuana use and arrested Smith. They handcuffed her. They handcuffed her aunt. An employee with social services took Audrey back to her paternal grandmother, and Smith was held in jail for three days.

On the third day, she was driven to family court for a hearing concerning the emergency removal of her son, Aiden. In cases of alleged unlawful conduct toward a child, all of the children are at risk of being taken from their homes and being placed with relatives, family friends, or into emergency foster care. That day, a worker from social services showed up at Aiden’s daycare and drove him away, placing him in care.

For weeks, Smith’s mother, Toni, says, the morning Aiden was taken from her replayed in her mind. Aiden “didn’t want to go to school,” she recalls. “I finally convinced him to go, and we got in the car, and I dropped him off. I didn’t know he wouldn’t come home for almost three years.”

Eventually, Aiden was placed in foster care, and for two years, the state pushed to end Smith’s parental rights. She had to have supervised visitation not just with her baby girl, but with her son as well. But she and her mother fought back.

Toni cleaned houses, and Smith managed a Domino’s Pizza; both pulled together money to pay for lawyers and for Smith to undergo state-sanctioned treatment plans, including what felt to her like an endless series of mandated programs: drug treatment, parenting classes, and both domestic violence victim and perpetrator classes, even though she had never been accused of violence against her children.

During this period, Smith was in and out of a tumultuous relationship with Audrey’s father. She says she felt trapped in their cycle—he promised to change, and she wanted her family together, especially as his mother had custody of Audrey. She says things would be okay for a while and then become toxic again. She struggled with her mental health and suicidal ideation.

Eventually, however, Smith was able to complete her treatment plan, and, in 2022, a family court judge ordered Aiden to be returned to his mother and their family. “He still hasn’t recovered,” Toni says.

In the meantime, Smith’s criminal trial has been delayed over and over.

At one point, Smith also was offered a plea deal—her charge would have been reduced to misdemeanor cruelty to a child—but she rejected it. “I don’t believe in pleading to something I didn’t do,” she says. According to data collected by the public defender’s office of Greenville County, at least 35 women across South Carolina have been charged with unlawful neglect of a child for cannabis use while pregnant. Smith’s is the rare case to go to trial.

“A lot of these cases start by prosecutors taking laws that already exist and applying them in ways that the legislator do not intend, or even sometimes applying laws that don’t exist at all to prosecute pregnant people,” explains Carpenter of Pregnancy Justice. “These cases are really driven by prosecutorial discretion.

“Even in a state like Alabama,” he continues, “which prosecutes these cases at a higher rate than any other state in the nation, over half of the prosecutions happen in one county, [Etowah]. They’re driven by one prosecutor wielding their discretion in a really aggressive fashion. So it’s really important to keep an eye on that granular level.”

But in July, Smith’s prosecutor left the office, and another was assigned to replace her. (A spokesperson from the 13th Circuit Solicitor’s Office declined to comment on this case.)

“I just want this to be over,” says Smith. “I just want whatever life I have left back.”

FIGHTING THE LAW, YEAR AFTER YEAR

By the time the judge evaluates the merits of Smith’s criminal case, it will have been five years and a day since Smith gave birth to her youngest.

Smith and her family—especially her children, Aiden, Aniyah, and Audrey—have each paid a steep price for the state’s commitment to her criminal prosecution. Smith sometimes lapses into serious depressive episodes, especially after visits with Audrey.

“I feel really guilty because I have kids and a son that I fought for, but I’m tired of feeling stuck. I’m tired of being unhappy,” Smith says. “I’m angry and I’m mad because—I don’t know. I’m angry at myself, at the circumstance, at the situation, at all of it.”

Audrey still lives with her father’s mother. By all accounts, she’s well cared for and deeply loved, but she wants her mother. After every visit, Smith says that Audrey asks if she can leave with her. Smith has to tell her daughter that she cannot.

To date, there is no evidence that Audrey has suffered developmentally or physically because of her mother’s marijuana use during pregnancy. “Her baby was healthy at birth,” Carpenter points out. “Her baby is still healthy. Her toddler, I should say, is still healthy.” The state’s behavior, however, has tormented Smith, and her mother, Toni, is witness to her daughter’s pain. “I’ve long stopped sleeping,” she says. “I wake up in the middle of the night, scared of what Lauren might do—to herself. She’s undone by this. I’m worried about what this has done to her.”

“Her baby is still healthy. Her toddler…is still healthy.”

Carpenter believes Smith’s case could have broad implications, both on a state and national scale. “If she were to be convicted, it would tell pregnant people in South Carolina and pregnant people in other states that prosecute these types of crimes, you are right to be suspicious of your healthcare providers, and you should think twice before you go to the doctor, which is horrifying.”

But Smith is determined to see this case through. “It just enrages me how, as a woman, as a woman of color, as a human being, carrying a baby—and to be treated like nothing, like a criminal,” Smith says. “I am telling you, I didn’t go through this for no reason.”

She says that telling her story and having it heard has given her purpose—a reason to endure what has otherwise felt like a hopeless and neverending reality.

“I want to prove that just because you are scared, it doesn’t mean that you give up. You have to push through the fear,” she says. “I’ve been afraid of a lot of things, but I wouldn’t be here today if I wasn’t afraid and persevered through that.”

If you or someone you love is thinking about suicide, you can call or text 988 for confidential support.

Neda Toloui-Semnani is an Emmy-winning journalist. Her work has appeared in numerous publications including VICE News, The Cut, and The Washington Post, among others. Her first book is They Said They Wanted Revolution: A Memoir of My Parents. Please visit www.nedasemnani.com for more information.

Why Do Men Love Telling Women to Have Babies?

November 2, 2023NEWS,NEWSLETTER

|

No images? Click here  November 2, 2023 Hey, Meteor readers, Next Tuesday is Election Day! If you haven’t already, make sure you know your polling place and have a plan to vote, even if the lines are massive. We cannot say it enough: Local elections matter. In today’s newsletter we’re talking about babies, mourning two feminist leaders, and sharing some weekend reading. Researching school board candidates, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONThe birth economy: During the opening of China’s National Women’s Congress last month, President Xi Jinping laid out a comprehensive and innovative plan for reviving China’s economy: Women, please get married and have babies. “We should actively foster a new type of marriage and childbearing culture,” he said, making no mention of women who work outside the home (and, presumably, have something to contribute to the economy themselves). In the face of economic decline and a slowly shrinking population, Xi has turned to a well-worn reactionary directive currently enjoying a revival in the U.S., too: ask women to stay home and raise the next generation of workers rather than find those women jobs and childcare. Despite its name, the Women’s Congress is not a legislative body but an event that occurs every five years to discuss women’s issues. And who gets invited to this prestigious event? China’s predominantly male National People’s Congress, comprised of delegates from various regions. (Their gender ratio is better than the Politboro, Xi’s executive policymaking body, where there are exactly zero women.) During his speech, Xi urged his audience to “tell good stories about family traditions and guide women to play their unique role in carrying forward the traditional virtues of the Chinese nation.” What a poetic way to tell half the population to shut up about their careers and reproduce.  PRESIDENT XI JINPING AT THE OPENING OF THE 13TH NATIONAL WOMEN'S CONGRESS. (IMAGE BY XIE HUANCHI VIA GETTY IMAGES) Speaking of babies: Meanwhile, over in America, conservatives who are badgering women to have babies are coming across more tone-deaf than usual, considering that those babies are dying at a higher rate than they have in 20 years. In the United States, which has the highest infant and maternal mortality rates of any high-income country in the world, deaths before a child’s first birthday have significantly increased this year, per a new report by the National Center for Health Statistics. For every 1,000 births in America last year, 5.6 babies died within their first months of life. While Black infants still have the highest mortality rate in the country, the year-over-year increase was sharpest for Native and white communities. Experts can’t agree on what’s contributing to the rise in deaths, but two possible factors are the COVID pandemic and the fall of Roe, both of which fundamentally changed how Americans sought out and received medical care. Dr. Tracey Wilkinson, an associate professor of pediatrics in Indiana, told NBC News, “Anybody who’s in the reproductive health space could and did warn that this is the type of data we were going to start seeing when we took away the federal protections to abortion access.” AND:

MAY THEIR MEMORY BE A BLESSING

WE'RE GIVING AWAY SOMETHING EXTRA SPECIAL THIS MONTH! FOR EVERY FRIEND THAT SIGNS UP FOR THIS NEWSLETTER USING YOUR ▶️ UNIQUE SHARE CODE ◀️ YOU'LL BE ENTERED INTO A DRAWING TO WIN TWO FREE TICKETS TO MEET THE MOMENT AT THE BROOKLYN MUSEUM DON'T HAVE A CODE? GET ONE HERE!  WEEKEND READING 📚On grief: The videos and photos of the carnage in Gaza are crushing to look at. But as my former colleague Samer Kalaf writes, “Sharing these videos feels like the only way to acknowledge these killings in a moment where many perceive them only as numbers in a news article.” (Defector) On hindsight: Rep. Barbara Lee famously voted against what would later become the ‘00s’ endless war on terror. She offers her thoughts on the value of restraint in the face of devastating violence. (Washington Post) On the happiest place on Earth: Writer Alana Levinson spends a spooky, surreal day at Disneyland with former Playboy bunny-turned-author and TikTok star Holly Madison. (Bustle)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

A purge in Ohio

October 31, 2023NEWS,NEWSLETTER

|

No images? Click here  October 31, 2023 Happy Halloween, Meteor readers, I’ve never been much of a costume girlie. I prefer Dia de los Muertos, which is celebrated in the days after Halloween. I love the idea of making the veil between the living and those who’ve crossed over a bit thinner. So remember to put out a candle and a little treat for your loved ones or any other spirits you’re welcoming. And if there are some ghosts you’re trying to avoid? Burn a little sage, name the ghost, and say aloud that they aren’t welcome. You can thank me later.  In today’s newsletter, we take a look at GOP tomfoolery in Ohio, the arrest of an Iranian hero, and an engagement announcement. Summoning spirits, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONThe Purge: Nearly 27,000 people just lost the ability to vote in Ohio. How does that happen, exactly? It’s routine to maintain the list of registered voters by removing those who change their names or have moved. But in the last decade, since a 2013 Supreme Court case gutted the Voting Rights Act of 1965, irresponsible purges are on the rise—and often come with a political motivation. This Ohio purge is particularly suspect because of its timing and, more to the point, because of what's on the ballot next week. Before they’re removed, voters are required to receive notification about the pending risk. But since those notifications can easily slip under the radar, it’s customary not to carry out a purge so close to an election. The fact that Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose scheduled this purge less than a week before Election Day has raised suspicions among his colleagues—especially because, just this August, LaRose delayed a purge until after a special election that included a GOP-backed measure meant to make it tougher to pass constitutional amendments. Which brings us to the heart of the issue: What exactly is LaRose preventing some Ohioans from voting on next week? A few things, but the big fish on the ballot is Issue 1, a measure that would amend the state constitution and “prevent the state from banning access to abortion, contraception, miscarriage care and other reproductive decisions.” LaRose knows the odds are stacked against him. Similar elections putting abortion on the ballot have resulted in a spate of pro-choice victories, even in conservative states like Kansas, Kentucky, and Montana. The GOP is fully aware that the majority of Americans support abortion access, and voter suppression is the only way to get around that inconvenient fact. (For a party that claims to hate government overreach, they’re giving extreme reach.) If Issue 1 does go on to fail by less than 27,000 votes next Tuesday, the purge may have been successful, and LaRose will have laid out a blueprint for other anti-abortion Secretaries of State looking to change the outcome of elections. These kinds of tactics are a reminder of just how much extremists rely on sowing confusion and making voting as difficult as possible. Don’t let them. AND:

Demonstrators rally outside the U.S. Capitol demanding a cease fire in Gaza on October 18. (Image by Chip Somodevilla via Getty Images)

WE'RE GIVING AWAY SOMETHING EXTRA SPECIAL THIS MONTH! FOR EVERY FRIEND THAT SIGNS UP FOR THIS NEWSLETTER USING YOUR UNIQUE SHARE CODE BELOW YOU'LL BE ENTERED INTO A DRAWING TO WIN TWO FREE TICKETS TO MEET THE MOMENT AT THE BROOKLYN MUSEUM DON'T HAVE A CODE? GET ONE HERE!  ICYMIDidn’t make it to Work Shift? We’ve got you covered! Enjoy this panel discussion featuring two HR execs who are letting us non-HR folk know what goes on behind the scenes—and how they're putting the “human” back into human resources. SPONSORED BY:  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()