HER LIFE WAS AT RISK. ALABAMA DIDN’T CARE.

October 27, 2024NEWSLETTER,FEATURED STORY

A home for modern feminism

Tamara Costa needed an immediate abortion. All she got was a sticky note with the phone number of a clinic 580 miles away. Here’s how one state’s severe laws punish families in terrifying health situations

BY JULIANNE ESCOBEDO SHEPHERD

Tamara Costa was over the moon when, in June 2024, she discovered she was pregnant for the second time. A 24-year-old logistics analyst in Athens, Alabama, she and her now-husband Caleb were already raising a toddler son, Xavier, and were eager to give him a sibling. They began saving for a larger house to accommodate a growing family. Tamara had gotten a pregnancy test at a Publix, sneaking away from her mom to buy it so she could surprise her. “As soon as it was positive, we ran to [Xavier’s] Grandma, like ‘Look!’” she says. “Everyone was all excited.”

But the day after she took the test, Costa began bleeding enough that she went to the hospital, where she says she was told that, four weeks into her pregnancy, she was having a miscarriage. The bleeding had stopped by the time she saw her OB-GYN but, after a routine check-up in mid-July—near the end of her first trimester—genetic testing found that the fetus had a high risk of triploidy, a usually fatal chromosomal abnormality. The OB-GYN then directed her to a maternal-fetal medicine specialist (MFM), trained to diagnose and treat high-risk pregnancies, an hour and a half away in Birmingham.

In early August, the MFM performed a high-resolution ultrasound—and the news was heartbreaking. The fetus didn’t have a skull, the specialist told them; the heart, liver and other organs were outside the body; the lower extremities couldn’t be seen at all. “I was pretty quiet, but my husband was like, ‘Are you sure your results are correct? Are you sure your ultrasound is up to date?’” Costa remembers. “I think we were just trying to hear that there could be a possibility of something different. But the specialist said that Baby would not survive outside of the womb, and there was nothing that we could do. And he said I could get sick, so termination was his only recommendation he was giving—and I had to go to my OB-GYN for more information on that.”

But the OB-GYN did not offer “more information”—at least not in the way they might have hoped. When Costa and her husband arrived at her appointment the following week, they say that the OB-GYN told them that, as they were in Alabama, there weren’t “a lot of resources,” but that she’d see what she could find.

Then she handed her a sticky note with a phone number and the words “Planned Parenthood Chicago” written on it. “She told me that she’d be willing to see me afterwards to do genetic testing, just to confirm that it was nothing with me that happened,” says Costa, “and that was pretty much the last time I heard from my doctor.”

THE LAW IN ALABAMA: AIMED AT “UTTERLY ISOLATING THE PERSON WHO IS PREGNANT”

Alabama is among the 14 states in the U.S. with a total abortion ban, in which the procedure is illegal in virtually all cases, at all stages of pregnancy. Under the law, which passed in 2019 but only took effect after the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision in 2022, performing an abortion is a Class A felony with a punishment of up to 99 years in prison, plus a $100,000 fine. Today, the state is fighting to put even more strictures on reproductive care; in February 2024, an Alabama Supreme Court ruling granted personhood to embryos, temporarily halting IVF in the state.

At the same time, Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall has made criminalizing abortion care and gender-affirming care a crusade, and has threatened to use an 1896 conspiracy law to criminalize anyone who helps a pregnant person travel out-of-state to obtain an abortion or even gives a patient information about how to do so. “If someone was promoting themselves out as a funder of abortion out of state,” Marshall told a radio show in 2022, “then that is potentially criminally actionable for us.” He then promised to “fully implement this law.”

Doctors and clinics have taken action to try to protect Alabama patients—including by suing to block AG Marshall from what they see as muzzling health-care providers. Robin Marty, the executive director of the WAWC Healthcare clinic in Tuscaloosa and a plaintiff in the lawsuit, says these laws are aimed at “completely and utterly isolating the person who is pregnant, because if you cut them off from information and any sort of assistance, then you have essentially isolated her and forced her to do what you want. And let’s be honest, that’s what domestic abusers do: isolate and then abuse and force them into what you want.”

Tamara and Caleb Costa at their wedding. (Photo courtesy of Tamara Costa)

Tamara and Caleb Costa at their wedding. (Photo courtesy of Tamara Costa)

There are resources for pregnant people in dangerous health circumstances—notably, abortion funds, which offer financial and logistical assistance. But pending the results of the lawsuit, none in the state of Alabama are currently allowed to operate, and Costa wasn’t aware of out-of-state resources that can help. So she and her husband maxed out a credit card to cover the expenses for the last-minute, 580-mile trip to Chicago—flights, rental car, hotel, food, and childcare for Xavier back home.

In the week leading up to Costa’s Chicago appointment, she began feeling even sicker, but her doctors couldn’t see her again before she left—and so, feeling neglected, she decided just to wait. When Costa finally arrived at Planned Parenthood on August 16, the clinic performed a routine pre-procedure ultrasound, and the OB-GYN on duty, Dr. Erica Hinz, went in to see the couple as soon as she’d reviewed it. Costa, she said, was experiencing a partial molar pregnancy, along with her fetus’s triploidy. (The Meteor has reviewed Costa’s medical records from Alabama and Illinois and confirmed these diagnoses and treatment.)

Dr. Hinz remembers that Caleb, in particular, “was really surprised to hear that. No one in her care up until this point had even mentioned the word molar pregnancy to her, right?” recalls the doctor. “I was very, very angry and very, very shocked.”

“IT SHOULD NEVER HAVE GOTTEN THAT FAR”

Molar and partial molar pregnancies are potentially life-threatening diagnoses in which an abnormal placenta grows at an accelerated rate; it can also develop precancerous cysts. The condition is rare, but can cause long-term complications; the placenta can grow into the muscles around the uterus and invade the pregnant person’s other organs, and the associated hyper-metabolism can cause anemia, heart attacks, and multiple-organ failure leading to seizure and stroke. The cysts within a molar pregnancy can also develop into cancer. Dr. Hinz says it’s rare to see a molar or partial molar pregnancy progress as far as Costa’s, because “with ultrasound technology these days, we catch it pretty early, and that’s why it’s become not as dangerous—because you catch it and you treat it early…In her case, it should have never gotten that far.”

The Costas with their son, Xavier, at Christmas. (Photo courtesy of Tamara Costa)

The Costas with their son, Xavier, at Christmas. (Photo courtesy of Tamara Costa)

Dr. Hinz knew that Costa needed termination immediately, but because Planned Parenthood was not equipped to perform a blood transfusion if she needed one, she urgently arranged for Costa to have the procedure done immediately at a nearby hospital. “Honestly, if she were delayed any further, I think she would have had a much worse outcome,” says Dr. Hinz.

“I was in surgery within, like, an hour of being there,” Costa says of her hospital experience. “At that point, I think we were terrified.”

If any delay was so risky, why was Costa forced to wait two weeks and travel three states away to get the healthcare she so clearly needed? In Alabama, there is one highly restricted exception to the abortion ban: Care is allowed only if there is serious health risk to the pregnant person, and if two Alabama-certified physicians have confirmed the diagnosis. Costa’s partial molar pregnancy could have met the criteria, if she’d had that diagnosis earlier, and it’s possible she could have received care in the state.

But advocates tell The Meteor there is no guarantee that any Alabama facility would have been willing to perform the procedure. The wording of Alabama’s abortion ban is confusing, and according to Robin Marty, has cultivated an environment in which doctors can be terrified to act on their diagnoses. This has “destroyed the doctor-patient relationship,” says Marty. “Patients can’t trust doctors, either because the doctors are withholding information because they don’t want a patient to seek an abortion for ‘moral’ reasons, or they are withholding the information in order to protect themselves from any sort of potential litigation or ending up in jail. But on the other hand…doctors can’t necessarily trust the patients. I know that at our clinic, when we have patients who say, ‘Okay, I want an abortion, where can I get it?’, we can’t trust that these patients are actually trying to seek out this information and not trying to entrap us. So now the doctors can’t trust the patients, the patients can’t trust the doctors, and it has destroyed the confidence in the medical system at all. And so how are we supposed to deal with these extraordinarily life-threatening conditions when nobody can provide the information that needs to happen in order to make a good decision for the patient?”

The Costas’ experience reflected this fear-filled medical environment. Caleb Costa remembers that the doctors in Alabama were speaking in euphemisms. “They used the term ‘because of what’s going on,” he says. “‘In our current’ you know, ‘environment,’ there is not much we can do about it unless the heartbeat stops.”

“THIS ISN’T A DEMOCRAT OR REPUBLICAN THING…IT WAS ABOUT MY HEALTH.”

Tamara and Caleb Costa met at the University of Alabama through mutual friends. They’d both grown up in the same area of Kentucky, and were living quiet lives that revolved around work, family, and University of Alabama football. Tamara never thought she would have an abortion herself, though she didn’t think her beliefs should restrict how another person might feel. But this experience has changed them both, and the trauma is still fresh. “This isn’t a Democrat or Republican thing,” she says. “It was human rights. It was about my health.”

Of the laws that put her in danger, Costa continues: “It seems like they’re concerned with life, right? [But] the only person that was affected was me. They said the baby wasn’t compatible with life. The only life that was affected in this [situation] was the living one. The only one that could survive was me. And it wasn’t a priority…The state, by making the decision for me, was essentially saying Baby’s life was already gone—so we were both gonna die.”

“Everything I enjoy doing mostly revolves around my family,” says Tamara Costa, here with Caleb and Xavier. (Photo courtesy of Tamara Costa)

“Everything I enjoy doing mostly revolves around my family,” says Tamara Costa, here with Caleb and Xavier. (Photo courtesy of Tamara Costa)

It was “like she didn’t matter,” says Caleb Costa through tears. “Her life was at risk and it didn’t matter to anybody. She didn’t have an option here to get help, and that’s not fair to her… We were told we needed to terminate our child in Alabama, but Alabama said, you can’t do it here. Make it make sense.”

Back in Huntsville, Costa and her family are still dealing with the ripple effects of their ordeal. “Everything I enjoy doing mostly revolves around my family,” she says, including her three new siblings—foster kids whom her parents recently adopted. Tamara, Caleb, and Xavier have moved to another house, but they’re still paying off their credit card debt for their Chicago trip. They’re taking in every Crimson Tide game and watching their fantasy football brackets, but Tamara regularly sees a new local OB-GYN recommended by Dr. Hinz, because they have to monitor her blood on a weekly basis for any residual health risks from the partial molar pregnancy, which can continue to cause dangerously high hormone levels even after it’s treated. And, in fact, her levels of hCG—the hormones produced by pregnancy or cancer cells—still haven’t gone back down to zero.

But the couple is trying to both honor their baby and still move on. “I lost a part of me,” Tamara says. “So we were trying to figure out how we were going to keep that memory.”

“We decided we wanted something that was living and could grow.”

Late this summer, Caleb and Tamara bought a baby plant from a botanical garden in Huntsville. They tucked the ultrasound photograph into it, so that as the plant grows, “Baby is still growing with us.”

“We’ve just been trying,” Tamara says, “to heal the best way that we can.”

Julianne Escobedo Shepherd is a Xicana writer, editor, and co-founder of the music and culture publication Hearing Things. Her first book, Vaquera, about growing up Mexican American in Wyoming and the myth of the American West, is coming soon from Penguin.

Read more about the medical facts of Tamara Costa’s case here. And read more United States of Abortion reporting here.

Video Credits

Director: Amy Elliott

Editor: Dana Cataldo

DP: Brack Bradley

Camera: Jacob Cantrell

Audio: Neil Bagley

Producer: Annie Venezia

![]()

This film is a project of The Meteor Fund, and produced in partnership with Harness; with support from Pop Culture Collaborative.

WHAT IS A PARTIAL MOLAR PREGNANCY?

October 27, 2024NEWSLETTER,FEATURED STORY

A home for modern feminism

Tamara Costa’s diagnosis, explained

BY MEGAN CARPENTIER

Tamara Costa faced two intertwined diagnoses: a partial molar pregnancy and a fetus with triploidy.

Molar pregnancies, explains Jennifer Conti, M.D., an OB-GYN and Complex Family Planning Specialist at Stanford Hospital, are “a very rare complication where the cells that will form the placenta go haywire.”

In both a molar pregnancy (one with no fetus) and a partial molar pregnancy (one with an abnormal fetus), the placenta includes cysts producing high levels of the pregnancy hormone hCG. Diagnosis usually occurs during the pregnant patient’s first ultrasound, and the only treatment is termination. Patients who aren’t treated early can suffer life-threatening complications, including sepsis, preeclampsia, shock, and uterine infections. The abnormal tissue can also grow into their abdominal muscles and/or cause cancer.

In addition, Tamara’s fetus had 69 chromosomes instead of the expected 46—a condition known as triploidy. It happens when one parent contributes two sets of their own chromosomes during fertilization, and can often also cause a partial molar pregnancy. Triploidy causes severe birth defects and usually results in miscarriages; the few fetuses that survive to term usually die within days.

“This goes to show how complicated and complex reproductive healthcare can be—and another reason why the doctor should be one making these decisions,” Dr. Erica Hinz, an OB-GYN with Planned Parenthood Chicago, told The Meteor.

Read more about Tamara Costa, and the laws in Alabama, here. And read more United States of Abortion reporting here.

Video Credits

Director: Amy Elliott

Editor: Dana Cataldo

DP: Brack Bradley

Camera: Jacob Cantrell

Audio: Neil Bagley

Producer: Annie Venezia

![]()

This film is a project of The Meteor Fund, and produced in partnership with Firebrand and Obstetricians for Reproductive Justice; with support from Pop Culture Collaborative.

"I Felt Like a Piece of Meat"

October 24, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, Today, someone on my Instagram feed noted that we are nine weeks away from Christmas, and somehow, that feels a little too close for comfort. I mean, who’s trying to go holiday shopping after we step out of the voting booth? Anyone? No? In today’s newsletter, a new woman has stepped forward to accuse Trump of sexual violence. Plus, troubling pre-election lawsuits, farewell to a true gem, and your weekend reading list. This year was ten minutes long, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONAnother day, another Trump accuser: During this week’s Survivors for Kamala Zoom call, Stacey Williams, a former Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Hall of Fame model, shared that in 1993, she had been groped by Donald Trump while she was visiting Trump Tower with Jeffrey Epstein. Williams alleges that Trump touched her breasts, waist, and butt while he and Epstein continued to chat and smile at each other. “I felt shame and disgust as [Jeffrey] and I went our separate ways,” Williams told The Guardian. “I had this horrible pit in my stomach that it was somehow orchestrated. I felt like a piece of meat.” A spokesperson for Trump called the allegations “unequivocally false” and a “fake story.” Williams is part of a growing group of at least 26 women who have accused the former president and now-candidate of sexual misconduct or abuse. (Trump continues to deny any wrongdoing, but last year, he was found liable for sexually abusing E. Jean Carroll by a court of law.) There are many things to say about these new charges—which you can watch Williams recount here—but one is: It is simply not normal that so few people are talking about them. Back in 2016, the release of audio of Trump bragging about sexual assault felt like a seismic turning point in the race. (Trump even apologized, which seems unthinkable now.) But eight years and dozens of allegations later, Trump’s behavior towards women is often treated less as a dealbreaker and more as a bothersome personality trait—well, that’s Trump, he’s a creep, move on! Still, in other ways, we’ve made some progress: In 2024, sexual assault victims are more likely to be taken seriously than they used to be (certainly more so than in 1999, when only a third of the public believed Juanita Broaddrick’s story of Bill Clinton raping her). More people believe women, it seems. Now all we have to do is get people to care. AND:

THE QUEEN OF THE TETONS, 399, PLAYING WITH SOME OF HER CUBS IN 2020 (VIA GETTY IMAGES)  WEEKEND READING 📚On keeping the fight alive: The women of Afghanistan have fallen out of Western headlines, but they’re still marching on the streets of Kabul. (The Persistent) On the newest political force: Parents are tired of being invisible to candidates, and they’re finally speaking up about it. (The 19th) On the woman behind the man: How do we better understand Usha Vance, an intelligent, successful woman of color married to a borderline white supremacist? Irin Carmon investigates. (The Cut)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

A "Strange Sorority" Unites Against Trump

October 22, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, Despite the Eric Adams of it all, this is truly a great time to be a New Yorker. We’ve got this year’s NWSL champions, the WNBA champions, and the Yankees are going to the World Series where we presume they will become champions for the 28th time. If you thought we were obnoxious before, you’re in for a real treat.  In today’s newsletter, survivors of sexual violence are banding together to keep Trump out of office. Plus, WNBA players are ready to stand on business, and a new bump to the legacy of our Tejana queen, Selena Quintanilla. NY or nowhere, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONSurvivor power: Yesterday a group of survivors of sexual and gender-based violence, and their allies, took out a full-page ad in The New York Times endorsing Kamala Harris for president and reminding readers that “Donald J. Trump was found liable for sexual abuse in a court of law…this is not a matter of opinion; it is a fact.” The letter was a call to anyone who cares, even one iota about the issue that allowing a known abuser into the White House (again) would be anathema to fighting gender-based violence in America.  IMAGE COURTESY OF SURVIVORS FOR KAMALA Last night, the group behind the ad, Survivors for Kamala, hosted a Zoom call led by advocates like Tarana Burke, Professor Anita Hill, Hadley Duvall, Ashley Judd, Brittany Packnett Cunningham, and not one, not two, but three members of what Alva Johnson called the “strange sorority” of women who have accused Donald Trump of sexual abuse. Johnson, who has accused Trump of forcibly kissing her, described his second campaign as “a nightmare that just doesn't end…like the Friday the 13th horror movies,” then promised to “do everything we can to keep him out of office.” As Burke put it on the Zoom call, “there is no collective power greater than survivor power”—not least at the voting booth. Speaking of: We are a very short two weeks away from election day. For the love of all things good, make a plan, know where you need to go, and cast your vote. Do it today, if you can! Polls are open virtually everywhere. AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

How Much Do You Know About Menopause?

A new documentary might teach you things about your own body that your doctor won’t.

By Vivian Manning-Schaffel

The migraines, joint pain, night sweats, and debilitating brain fog began in my mid-forties. With two young children to keep up with, there wasn’t enough coffee in the world to make me feel present. I had an inkling I might be perimenopausal, but no one—not even my OB/GYN at the time—sat me down and told me what I was experiencing was normal, let alone offered me treatment options.

I, for one, would’ve greatly appreciated if a new documentary, The M Factor: Shredding the Silence on Menopause, came out a decade ago when my hormonal shenanigans began. Produced by Tamsen Fadal and Denise Pines, it’s airing tonight, Wednesday October 17, on PBS, right in time for World Menopause Day on 10/18. It’s the first menopause film to earn medical accreditation, meaning doctors and nurses can earn credits just by watching it.

In 2025, more than 1 billion women worldwide will be in menopause, after a five-to-ten-year period of symptoms ranging from hot flashes and mood swings to vaginal dryness and heart palpitations. Yet, even though menopause is as natural as puberty or childbirth, it has long been criminally neglected, under-researched, misdiagnosed, and mistreated. Too many women aren’t properly informed before the signs kick in, are gaslit or dismissed by their doctors when said symptoms show up, and end up feeling like they’re going insane.

The documentary fills in some of these gaps, explaining what to expect when you’re done with the possibility of expecting from a medical, emotional, cultural, and historical perspective. In the absence of widespread guidance, some of the doctors featured have become revered social media heroes. For example, Dr. Lisa Mosconi, a neuroscientist and author of The Menopause Brain, discusses her important study demonstrating how estrogen connects to brain health and cognitive function because we have estrogen receptors in our brains—one of many key findings in support of Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) as the gold standard of menopause treatment.

It took a while to get to that gold standard: The documentary takes us through the devastating impact of a flawed as-hell 2002 Women's Health Initiative study falsely claiming HRT increased the risk of blood clots and breast cancer—a good section of the homogenous group of subjects were well into their seventies and could’ve been diagnosed with those conditions, anyway. Mary Jane Minkin, MD, a clinical professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Yale School of Medicine who appears in the documentary, told me when this study came out, doctors stopped prescribing HRT, and menopause education in the U.S. all but ceased. More than 20 years later, she added, a study led by a colleague of hers proved less than a third of the OB/GYN residents surveyed were taught a menopause curriculum.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RmrMwBh7l8w

Fortunately, a far more inclusive, age-appropriate, longitudinal study about women in midlife called the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation eventually disproved the WHI study, restoring the credibility of HRT. For me, it took several years of complaining, writing an article about the efficacy of HRT, and a series of tests to convince my OB/GYN to give me a prescription. Now that my sleep has largely been restored, my joints feel better, and my brain fog has immediately cleared, I mourn the years I struggled through symptoms for absolutely no reason.

The documentary takes care to note that menopause isn’t a one-size-fits-all experience. The severity and length of symptoms can vary greatly depending on who you are; they can last an average of 4.8 years for Japanese-American women and an average of 10.1 years for Black women. It also delves into the dark history of inequities of gynecology, including how Black enslaved women’s bodies were experimented upon by American gynecologists and the fact that Black women still suffer adverse outcomes and maternal mortality at disproportionately high rates.

Things seem to be slowly changing for the better: President Biden signed an executive order that allocates 12 billion dollars to women’s midlife research—something Minkin hopes will further inspire young medical students to follow in her footsteps: “I try to trick my medical students into going into menopause research because I guarantee you there’s a Nobel prize for the person who can figure this out,” she says in the documentary.

The filmmakers hope all women will learn more about menopause—even if they’re not there yet. Whether or not we eventually seek treatment for symptoms is up to us, but Sharon Malone, MD, another certified menopause practitioner, says in the doc that we may be doing our bodies a disservice by white-knuckling it. “The option should be, ‘I’m going to go, I’m going to get this addressed’ not ‘I’ll just suffer through and it’ll be over in a decade,’” she says. “You’re doing far more harm than good by just not addressing what the issues are.”

Vivian Manning-Schaffel is a journalist and essayist who covers entertainment, culture, psychology, and women’s health. Her Substack, MUTHR, FCKD, covers pop culture through a feminist Gen X lens.

The "Zombie Law" That Won't Die

October 17, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, And an especially warm hello to Breanna Stewart, who last night hoisted the New York Liberty onto her back and carried them to a 2-1 lead in the finals by dropping 30 points on the board. This is our year!  In today’s newsletter, we learn about the latest attack on mifepristone, the abortion pill. Plus, a new documentary out today is helping to push us down the road to understanding menopause. And we’ve got your must-reads for the weekend ahead. Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONThe “zombie law” that won’t die: Yesterday, Abortion, Every Day founder Jessica Valenti broke the news that the Attorneys General of Kansas, Missouri, and Idaho had quietly filed a lawsuit against the FDA attempting to severely restrict access to mifepristone, one of the two medications used to induce abortions. Using an 1873 “zombie law” called the Comstock Act, the suit seeks to ban (among other things) the shipping of abortion medication—which nearly 20% of people who get abortions rely on. If successful, the ruling would apply across the country, including in pro-choice states. If all this sounds familiar, it's because anti-abortion activists have tried this before. In fact, this most recent suit was filed with Trump-nominated Texas judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, who ruled in favor of the previous mifepristone lawsuit before it was tossed out by the Supreme Court back in June. We knew this was coming; after the Supreme Court ruled that the previous plaintiffs did not have the proper standing to challenge the FDA, the only thing left to do for conservatives was to find new plaintiffs. Now, here they are. The timing of this lawsuit is perplexing, given that abortion restriction is a losing issue at the ballot box, and this is bound to make anyone who cares about it furious. Perhaps that’s why, as Valenti points out, none of the AGs involved in the suit have put out a press release. But make no mistake: Despite recent attempts at moderation, this is the GOP attempting a national ban. AND:

How Much Do You Know About Menopause?BY VIVIAN MANNING-SCHAFFEL A new documentary might teach you things your own doctor won’t.(VIA INSTAGRAM) The migraines, joint pain, night sweats, and brain fog began in my mid-forties. With two young children to keep up with, there wasn’t enough coffee in the world to make me feel present. I had an inkling I might be perimenopausal, but no one—not even my OB/GYN at the time—sat me down and told me what I was experiencing was normal, let alone offered me treatment options. I, for one, would have greatly appreciated it if the new documentary The M Factor: Shredding the Silence on Menopause had come out a decade ago when my hormonal shenanigans began. Produced by Tamsen Fadal and Denise Pines, it’s airing tonight on PBS, right in time for World Menopause Day tomorrow. It’s the first menopause film to earn medical accreditation, meaning doctors and nurses can earn credits just by watching it. (Which is a good thing, since many of them don’t actually get taught this stuff in medical school.) In 2025, more than one billion women worldwide will be in menopause, after a five-to-ten-year period of symptoms ranging from hot flashes and mood swings to vaginal dryness and heart palpitations. Yet even though menopause is as natural as puberty or childbirth, it has long been criminally neglected, under-researched, misdiagnosed, and mistreated. Too many women are blindsided by symptoms, gaslit or dismissed by their doctors, and end up feeling like they’re going insane. Building on a recent wave of menopause journalism, the documentary fills in some of these gaps, explaining the experience from a medical, emotional, cultural, and historical perspective. In the absence of widespread guidance, some of the doctors featured have become revered social media heroes. Dr. Lisa Mosconi, a neuroscientist and author of The Menopause Brain, regularly shares her work with her hundreds of thousands of Instagram followers—including her major study linking estrogen to cognitive function and establishing Hormone Replacement Therapy as the gold standard of menopause treatment. It took a while to get to that gold standard: The documentary takes us through the devastating impact of the flawed-as-hell 2002 Women's Health Initiative study, which found that HRT increased the risk of blood clots and breast cancer, even though many subjects were well into their seventies and at high risk for those conditions anyway. After that study came out, many doctors stopped prescribing HRT, and what little menopause education there was in the U.S. basically ceased, says Mary Jane Minkin, MD, a clinical professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Yale School of Medicine who appears in the documentary. More than 20 years later, she told me, a study led by a colleague of hers proved that less than a third of the OB/GYN residents surveyed were taught a menopause curriculum. Fortunately, a far more inclusive, age-appropriate, longitudinal study about women in midlife called the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation eventually disproved the 2002 study, restoring the credibility of HRT (and helping bring about the treatment’s current popularity). For me, it took several years of complaining, writing an article about the efficacy of HRT, and a series of tests to convince my OB/GYN to give me a prescription. Now that my sleep has largely been restored, my joints feel better, and my brain fog has cleared, I mourn the years I struggled through symptoms for absolutely no reason. The documentary takes care to note that menopause isn’t a one-size-fits-all experience. The severity and length of symptoms can vary greatly depending on who you are; they can last an average of 4.8 years for Japanese-American women and an average of 10.1 years for Black women. Systemic racism can play a part in one’s experience with menopause, the documentary explains: It delves into the dark history of inequities of gynecology, including how Black enslaved women’s bodies were experimented upon by American gynecologists and the fact that Black women still suffer adverse outcomes and maternal mortality at disproportionately high rates, often because they’re not listened to by their doctors. Things seem to be slowly changing for the better: President Biden signed an executive order in March that allocates 12 billion dollars to women’s midlife research—something Minkin hopes will further inspire young medical students to follow in her footsteps. As she says in the documentary: “I try to trick my medical students into going into menopause research because I guarantee you there’s a Nobel prize for the person who can figure this out.” And in the meantime, say many menopause experts, we shouldn’t be white-knuckling it. “The option should be, ‘I’m going to go, I’m going to get this addressed,’ not ‘I’ll just suffer through and it’ll be over in a decade,’” says Sharon Malone, MD, another certified menopause practitioner, in the doc. “You’re doing far more harm than good by just not addressing what the issues are.”  Vivian Manning-Schaffel is a journalist and essayist who covers entertainment, culture, psychology, and women’s health. Her Substack, MUTHR, FCKD, covers pop culture through a feminist Gen X lens.  WEEKEND READING 📚On anti-abortion dogs: Investigative journalist Debbie Nathan reports out a tip about drug-sniffing police dogs in Jackson, MS, intercepting abortion pills in the mail. (The Intercept/Lux) On Ozempic: The drug has been touted as a miracle for weight loss and glucose management. It’s even been held up as a tool for aiding in the climate crisis. But the full story is a lot more complicated. (Atmos) On the small screen: The funniest and queer-friendliest vampires we’ve ever known are taking their final bow this month. How do we bid farewell to What We Do in the Shadows? (Vulture) 🦇 On music: What are the songs that define our decade? Luckily, someone made a list. (Hearing Things, a brand new website co-founded by beloved Meteor collective member Julianne Escobedo Shepherd 🥳)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

To Be Or Not To Be "Latina"

October 15, 2024 Happy Monduesday, Meteor readers, To mark the final day of Hispanic/Latine Heritage Month, we’re going to take a little stroll through the existential identity crisis of your favorite newsletter gal (🙋♀️). Plus, we’re taking a moment to salute the one and only Tarana Burke and applaud President Barack Obama’s words to Black male voters. And speaking of voting! We are three short weeks away from Election Day. Do you know where your polling place is? Is your registration up to date? Does your state have early voting dates available? Find out, make a plan, and #GetReadyWithUs by clicking here. Let’s get into it, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONMaking history: On this day seven years ago, #MeToo went viral, shedding light on the millions of people who have experienced sexual assault and harassment. It was a breakthrough moment. But for Tarana Burke, the woman who first used the term “me too” as a rallying cry back in 2006, it was a moment filled with fear. As she wrote in her memoir Unbound, she worried that the viral discourse, sparked by a white woman’s tweet, would erase her story and her work, focused on Black survivors, from history. Burke’s tenacity wouldn’t allow that to happen. She swiftly introduced the work she had been doing since 2006 to an audience of millions, and her organization, me too., is now a global network stationed in 34 different countries where sexual violence against women is on the rise. What began as a grassroots project to help women in her community is now one of the largest and most recognizable anti-violence movements in the world, giving survivors the tools they need to rebuild their lives. The words “thank you” don’t feel strong enough. AND:

To Be or Not To Be “Latina”That is the lifelong question BY SHANNON MELERO  A CHILDREN'S CHOIR IN TEXAS PERFORMS AT A COMMUNITY CENTER IN HOUSTON TO COMMEMORATE HISPANIC HERITAGE MONTH. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Today is the final day of Hispanic/Latine Heritage Month and as is the case every year, I find myself revisiting the question of what it means to be Latina, or as some people might dare to call me (but never to my face) a “whitetina.” I’m a Puerto Rican from the South Bronx, which felt to me for a long time like a race in and of itself. I knew who I was: I was the product of strict, loud, bold women, each varying shades of brown or beige. Everyone around me was Latine, Black, or a combination of the two. The smattering of white people in my life—teachers mostly—didn’t register in my mind as White People. They were just people who happened to be white. (Please know these two classifications are very different: whiteness is about one’s appearance, while Whiteness is appearance plus the lived myth of superiority.) Growing up, I was frequently reminded that as a light-skinned Latina, I looked and spoke like a White Person. This was intended both as an insult and a sort of gift. My proximity to whiteness meant I could ascend. I could be something. But the thing about being a person who happens to be or look white is that it doesn’t come with the same advantages or security as actually being a White Person.  MY MOM AND ME OUTSIDE OUR FAMILY'S HOME IN PATILLAS, PUERTO RICO. I'M TOLD THAT HAIRCUT WAS VERY FASHIONABLE FOR THE TIME. (COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR) Picture it! A bathroom, 2009: I had just gotten out of the showers in my freshman dorm and was building up the mental fortitude to finish detangling my very long, very unruly hair, which was being decimated by the hard water of upstate New York. As I stared down at my array of creams, oils, and combs, a girl walked in, struck up some small talk, and then, without invitation, touched my beautiful locks and said, “Your hair is so exotic.” At the time, I didn’t understand the gravity of that exchange. I was annoyed and offered up a fake laugh and an unconvincing nod. But now I realize it was the first moment I was confronted with the question of my own race and discovered that I didn’t actually have an answer. It was the first of many hard lessons of my college years. The White People saw immediately that I wasn’t white. To them, I was exotic. Loud. I pronounced “bagel” and “water” wrong. My body was proportioned strangely, an academic way of saying I had a big ass, and some of my floormates teased me about how hard it must be to find clothes that fit. Try as I might, and I tried very hard, I couldn’t squeeze into the mold of whiteness. So I decided I would be more Latina. Whatever that meant.  A 1940 CENSUS DOCUMENT WHERE MY GREAT GRANDFATHER, JULIO, HIS WIFE, AND HIS FIVE CHILDREN WERE LISTED BY A SURVEYOR AS BEING OF THE RACE "DE COLOR" MEANING THEY WERE "COLORED" BUT NOT BLACK. (COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR) To my utter dismay, it meant reading a lot of history and coming to grips with a litany of uncomfortable truths. The biggest of these was that “Latine” isn’t a race; it’s a racialized status, meaning it’s an invented labeling concept intended to group together a variety of people in one box. And as Laura E. Gomez beautifully explained in her book Inventing Latinos, the term “Latino” was primarily created to establish a race that was lower on the totem pole than White but still somewhat above Black (making it more difficult for the two “lesser” groups to demand the same rights of the first). After all, how can you systematically strip millions of people of their rights and dignity or justify a yearslong occupation of their lands if you don’t first strip them of the one thing that guarantees their protection: Whiteness? You make them something else. You make them something lesser. And then you give them thirty days to celebrate their “unity.” The failure of Hispanic/Latine Heritage Month is that it relies on the false premise of “Latinidad,” that we are all united because of the one thing we have in common: being colonized by Spain. But our actual heritage cannot be attributed to a single colonizer, nor can it be captured in a category rooted only in our post-colonial existence. The Taíno traditions and history of Puerto Rico are not the same as those of the Maya, the Aztec, the Inca, the Quechua, the Zapotec, the Macorix, the Arawaks, the Garifuna—I could go on.  MY GREAT-GRANDFATHER, JULIO, WAS NOT CONSIDERED BLACK IN 1940. HOWEVER, WHEN HE WAS REGISTERED FOR THE DRAFT IN 1942, HIS RACE WAS FILLED IN AS "NEGRO." (COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR) But when we celebrate Latine “heritage,” we’re not celebrating those cultures. We’re celebrating a Eurocentric, watered-down, post-Columbus, post-Spanish occupation version of ourselves. We’re celebrating who we became, not who we are. It’s a trap many of us are lured into at a young age. We’re trained to forget ourselves, only to learn that our skin color isn’t enough to grant us full White Privilege. And when we finally unlearn all of that, we find a beautiful, rich history waiting for us, along with enormous grief that we’ve wasted our lives assimilating and no longer feel a connection to who we are. We buy fully into the American dream only to find out that we can’t have it because we are not really white, not really American. And if I cannot be white or American, and I cannot be Latina because my Taíno ancestry is lost to time, then I have to ask: What am I allowed to be?  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

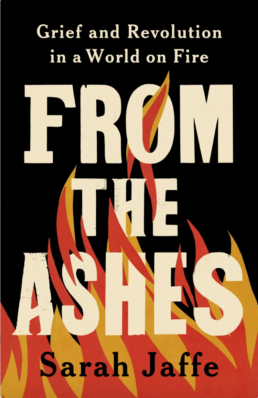

“Pray for the dead, fight like hell for the living.”

October 10, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, We’ve got a lot to get through today, but first, please indulge me for a moment. (Or just skip down to What’s Going On, I won’t take it personally.) Today is Samhita Mukhopdhyay’s last day as editorial director here. She’ll still be Meteor-adjacent, but I told her I couldn’t let her go without emailing her (and by extension, you) my farewell speech: Samhita, my Taurus twin, my fellow DDC member, you have been an incredible leader, a mentor, an unwilling recipient of my voice notes, a source of strength, and above all else, a friend. This departure feels like a death. But, if there’s one thing I believe in more than you and everything you are, it’s that not even death is permanent. So, no goodbyes. I’ll see you on the other side. ♥️ Speaking of grief, we chat with Sarah Jaffe about her new book on how mourning affects politics. Plus, the exciting conclusion of Fat Bear Week and some weekend reads. The last SM standing, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON

FAT BEAR QUEEN, GRAZER. (VIA NATIONAL PARK SERVICE)  It's a tool of revolution, author Sarah Jaffe explains.As the anniversary of Hamas’s October 7 attack on Israel approached, I prepared myself for anger and blame on social media. What I noticed instead was the palpable sense of grief that coursed through people—grief for what we’ve seen, what has happened since, and what we’ve lost. That’s actually not unusual: Collective grief plays a profound role in our politics; it can unite us and inspire change. But we don’t often give grief the space to truly transform us into better political citizens. I talked to the author and labor journalist Sarah Jaffe about how we might do that—a subject she takes up in her new book From the Ashes: Grief and Revolution in a World on Fire. Samhita Mukhopadhyay: Why did you decide to write about grief? Sarah Jaffe: The thing that got me started thinking about grief was the death of my father. [This book] takes our emotional lives seriously and argues two somewhat contradictory things: that grief is an integral part of being a full and complete human and also that the world creates so much unnecessary grief and pain and that we could, in fact, stop some of that. And then a third thing, which is that we ought to talk about it. When my father was ill, I had some idea that I could be good at grief, that I could work hard at it the way I had at everything else in my life. I was so wrong about so many things, but particularly the [fact that grief] will come when it comes and fade when it fades, and there is nothing you can do but ride the waves of it. This, of course, is a very difficult thing to accept in a world that runs on the time clock and the biweekly paycheck and in a country that doesn’t even give us health insurance, let alone expansive paid time off. Grief is mostly considered private, something you have to manage on your own. Can you talk about the importance of moving grief from the personal to the public? Nearly all cultures have grief rituals in which the community comes together to mourn. In the capitalist West, those rituals have been shortened and forestalled, if not ended altogether. Yet there have been moments in the last few years where the world seemed to erupt in collective grief. The George Floyd uprising [was] probably the largest of those, when despite lockdown orders people spilled into the streets and mourned and demanded change. Last week, I was in Minneapolis for a book talk, and I went down to George Floyd Square, where the names of people killed by police are still painted in the street and fresh flowers are still laid where George Floyd was killed and massive sculptural fists stand in the streets. The call “Black Lives Matter,” the demand to “say her name,” are calls for us to grieve. The demand “Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living”—taken from labor agitator Mother Jones—has been embraced by Jewish groups calling for a ceasefire in Gaza (and now in Lebanon and beyond). Such public mourning does more than bring us together—it calls on us to think about the world we live in, and the harm that it does every day, and how we might imagine it differently. When my father died, I remember you reached out with a beautiful letter of advice on how to navigate what was to come. I loved seeing in the book that someone else had done that for you. Why do you think this act of reaching out with wisdom in moments of grief is so important? Grief is universal, and yet it can feel so profoundly isolating when it happens to us. No one, it seems, understands. Except then the people who do understand start to find you, and they share little or big bits of wisdom, and they hold you when you need holding, and they tell you their stories. This book is a way of paying forward the care I got from people when I didn’t remember my own name and couldn’t remember to eat. [It’s a way to show] that maybe the world is built [not] on transactional, one-to-one reciprocation, [but rather] on what philosopher Eva Kittay calls nested caring obligations. I live in New Orleans, and like a lot of people this past week, I have been haunted by the destruction done by Hurricane Helene in places that are nowhere near the coast and are hundreds or thousands of feet above sea level. So many people here have been reaching out with money and time and donations and fundraisers for people we’ve never met in another part of the country, because we know what it’s like to face climate disaster. We build solidarity with those acts of care, without asking for them to be directly repaid.  WEEKEND READING 📚On the great outdoors: Meet Rhiane Fatinikun, the founder of Black Girls Hike. (The New York Times) On the stuff of parents’ nightmares: After her children’s nursery temporarily lost their license, journalist Atossa Araxia Abrahamian set up a makeshift daycare in her living room—and nearly lost her sanity. (The Cut) On the gender cleanliness gap: Anne Helen Petersen explains why women—even child-free ones—are trained to “serve our spaces.” (Culture Study)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

It's Been a Bad Week for Abortion

October 8, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, This week last year, we sent you a newsletter grappling with Hamas’s October 7 attack on Israel, and it remains one of the hardest we’ve ever had to compose. In the immediate aftermath of the attack, we were grief-stricken, angry, and fearful of impending violence. “What is happening cannot fit in an easy tweet or cleverly worded Instagram post,” we wrote at the time. “Honestly, it can’t even fit in this newsletter.” That truth still holds. Since then, we have witnessed children left to starve to death. Hostages treated as dispensable pawns. Women giving birth in the rubble of bombed hospitals. We’ve also seen and been part of a larger awakening—about how connected we all are to what happens half the world away and about the difference our actions, our tax dollars, and our votes make. And while that awareness will not bring back the thousands who've lost their lives, it’s a better place from which to move forward than willful ignorance. Perhaps we can spend this next year looking for peace. There is another way, The Meteor  WHAT'S GOING ONThis week in abortion: It’s not great! Yesterday, Georgia’s Supreme Court reinstated that state’s six-week abortion ban. Judge Robert C. I. McBurney had overturned the ban last week on the grounds that it was not in line with the state’s constitution. But local Republicans immediately started filing appeals, and until they’re sorted out, the original ban will be the law of the land. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court, ambling its way back to the bench for the start of a new session, has declined to weigh in on a case in Texas involving a federal emergency care law (EMTALA) that requires any hospital receiving Medicare funds to provide abortions in emergency situations. For now, the existing language in the state’s ban will remain unchallenged. Why is it playing out this way? Because technically, Texas’ abortion ban already has a carve-out for emergency situations, making it EMTALA-compliant. However, as we’ve seen time and again (and as Amanda Zurawski can attest), those exceptions are so vague that, in practice, women often have had to be actively dying before a doctor grants an abortion—and sometimes, as in the case of Amber Thurman, life-saving care comes too late. AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

New Tie, Same Old Misogyny: J. D. Vance's Failed Rebrand

October 2, 2024NEWS,FEATURED STORY

By Shannon Watts

Since becoming the vice presidential nominee almost three months ago, J. D. Vance has taken almost constant fire for his long history of denigrating women, including comments on podcasts about the tragedy of remaining childless, the misery of women who work outside the home, and the duty of every post-menopausal woman to serve as stop-gap childcare for her family. As a result, Vance has the worst net favorability rating for any vice-presidential candidate in history and has become a walking meme for masculinity gone wrong.

Last night, in an attempt to shed that electoral albatross, we watched in real-time on live television as Vance attempted a calculated rebranding of himself as an ally to women everywhere.

From the glaring symbolism of Vance’s Barbiecore tie (instead of the traditional red tie Republicans typically wear) to his constant shoutouts to the women “very dear to me” (including his mother, grandmother and several anonymous women he claims to know who have been through some things), Vance worked hard to project feminine energy—someone who listens, who feels empathy, who might be open to changing his mind. But instead of embodying any of those things authentically, Vance’s debate performance came off like cosplay. This stab at a rebrand was as transparently pink-washed as his tie.

For me, Vance’s mask fell off a few times during the debate. It started when the two women moderators interrupted him for not following the agreed-upon rules, even cutting off his mic. Testy and defensive, Vance talked over them with the now-famous complaint, “The rules were that you guys weren’t going to fact check.” And even though he tried to camouflage it, Vance couldn’t disguise the misogyny that has underpinned his policy platform for decades. Moderator Margaret Brennan ended the exchange by quipping, “Thank you for explaining the legal process,” in a tone that struck a chord with every woman who has ever been mansplained to in a meeting.

When the issue of childcare came up, he implied he supported efforts to make it more affordable—even though he skipped the Senate vote for an expanded child tax credit. When abortion came up, Vance implied he didn’t support a national ban—when, in fact, he has stated publicly that he does. He told the story of a friend who needed an abortion in order to leave an abusive partner—but failed to mention the laws he supports would have instead prevented her from leaving.

But even more revealing, whenever issues like those were discussed, Vance made it clear that he sees those issues as only impacting women, as if they’re somehow untethered from any broad economic and societal implications or don’t also affect women’s partners, children, bosses, everyone. When he spoke about wanting the Republican party to become “pro-family in the fullest sense of the word,” he meant “making it easier for moms to afford to have babies.”

Even the new incarnation of Vance fails to understand that the “women’s issues” discussed during the debate are actually issues that impact everyone’s lives. The lack of high-quality, affordable childcare hurts parents, children, and employers alike. And restricting women’s rights restricts the freedom of all. We now live in a world where men are actively advocating for paid family leave and supporting abortion rights. But in his attempt to modernize his stance on these issues, Vance just wants to tell us about a woman he “knows.”

Despite Vance’s best efforts to rebrand, women wisely saw through his performance for what it was: performative. According to a CNN instant poll, after the debate Walz had the advantage among women, rising 18 points in favorability. The message is clear: We simply aren’t buying the “new and improved” Vance he’s trying to sell us.

Shannon Watts is an author, organizer, and speaker. She founded Moms Demand Action and recently organized one of the largest Zoom gatherings in history, mobilizing women voters for the 2024 Kamala Harris campaign. Her new book Fired Up is coming in 2025.

Shannon Watts is an author, organizer, and speaker. She founded Moms Demand Action and recently organized one of the largest Zoom gatherings in history, mobilizing women voters for the 2024 Kamala Harris campaign. Her new book Fired Up is coming in 2025.