"Was It Foolish to Hope?"

November 8, 2024 Dear Meteor readers, I hope everyone has something—anything—fun planned for this weekend. (I’m taking my little one to her first gymnastics class and can already feel the gold medal.) In today’s newsletter, we’re parsing the aftermath of Tuesday’s election with Brittany Packnett Cunningham and the UNDISTRACTED group chat. Plus, some options if you’re looking for an election break. Onward, Shannon Melero  “WAS IT FOOLISH TO HOPE?”That’s the powerful, poignant question host Brittany Packnett Cunningham posed to group-chat regulars Dr. Brittney Cooper and Dr. David Johns this week on UNDISTRACTED. The morning after Vice President Kamala Harris conceded the election (but not, as she said, “the fight that fueled this campaign”), the three sat down for a raw, honest conversation about everything from “righteous rage” to “deep disappointment” at America’s rejection of a Black South Asian woman candidate in favor of an open white nationalist. We hope you’ll listen to the whole thing; here are some highlights: Brittany Packnett Cunningham on her immediate feelings: "There’s a rage that I have for the deep lack of solidarity, appreciation and fundamental respect for…the Black women who consistently do the custodial work of democracy and get left hanging out to dry every single time. And for me, it is punctuated by the fact that the night before we all gathered at Howard [for the election results], J.D. Vance stood up and said, “We’re going to take out the trash tomorrow…[and] the trash’s name is Kamala Harris.” He was talking about every single one of us in the moment that he did that. And…it barely made a blip. In fact, plenty of people said, That’s exactly what I wanna go vote for. Let me go take out the trash." "We delayed this episode by a day because I didn’t want to come with this energy. [But] I’m still in grief. Not over just a candidate or an election. Not just because…the worst is yet to come. But because there seems to be little, if any, repentance toward the absolute disappointment everybody continues to be to Black women. And every Black woman I talk to is ready to go on strike….So that's where I am today."  “EVERY BLACK WOMAN I TALK TO IS READY TO GO ON STRIKE...” (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Dr. David Johns on hope: "I want us to feel all of our feelings. And…the corollary of that for me is that there’s never been a chapter in the history of our people where our ancestors began or ended with '...and then we conceded,' or '...and then we gave up.' That is not in us." "Also, I am heartened by the reminder that Black people understood the assignment in spite of all the lies that the media tried to tell, blaming Black men. In spite of all of those lies, we, Black men and Black women [by voting overwhelmingly against Trump] demonstrated an understanding of the assignment to continue to care for one another while doing the work of creating the democracy that our ancestors fought and died for, and that we are fighting for today.”  HARRIS SUPPORTERS AT HOWARD UNIVERSITY ON THE DAY OF THE VICE PRESIDENT'S CONCESSION SPEECH (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Dr. Brittney Cooper on how Harris was viewed: "I’m managing rage at the white supremacy and the patriarchy and sexism and misogyny of it all for sure. I’m also managing deep, deep disappointment and fury at some pockets of the left—because I think that I witnessed an abdication of a race/gender analysis that would prepare us for this moment." "The left had this sort of narrative about how she was so much a representative of the Empire that they couldn’t trust her for progressive goals—but they didn’t realize that they were fighting against people who saw her as a Black girl [who] would never be worthy enough to actually run the country. There is no evidence that this country trusted a Black girl with an Asian mama to run it and do it with excellence. Most of the country looked at Kamala and didn’t see a representative of the Empire, but actually saw the opposite—saw a Black girl [who] could never be a sufficient representative of this empire. And that is how they voted." Listen to the full episode of UNDISTRACTED. You won’t be sorry. AND:

JENNIFFER GONZÁLEZ-COLÓN IN 2023. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

WEEKEND READING 📚

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

"I woke up worried for my daughter."

November 6, 2024 Dear Meteor readers, You’re getting this email approximately 12 hours after Donald Trump secured his second presidential victory, and only minutes after Vice President Kamala Harris conceded in front of a tearful crowd at Howard University. Trump’s decisive win is still a fresh wound: We’re only in the earliest minutes of figuring out what it means for not just our democracy but our actual, real lives: how we work, where we are safe, who we need to hold close. As a media outlet, The Meteor tries to bring you reasonably thoughtful stories, analysis and videos. But as a group of real people negotiating emotions, The Meteor had a day like everyone else, and may or may not have typed this from a fetal position on the couch. Rage, disorientation, and heartache for the many people who put their lives on the line for change were all part of the mix. So while there’ll be plenty of time for action steps in the weeks (and, realistically, years) to come, today is personal. In this newsletter, six of my colleagues tell you exactly what today felt like to them. (We did have a no-false-hope rule: “You know we’re not gonna kumbaya our way out of this,” Shannon said at our editorial meeting this morning.) Here are their reflections. And we want to hear yours—find us at [email protected], or, as always, here. Grateful for all of you, Cindi Leive  “We have never been safe.”A Trump win hits different as a tranny. In 2016, I was a 22-year-old gay boy living in Houston, and I was scared. The day after he won, some men in a pickup truck drove by me and yelled, “TRUMP WON, FAGGOT!” And, obviously, that felt bad. But now…? I have an appointment to discuss getting back on estrogen (had to stop after a health scare) set for January 30—ten days after the inauguration. And no, I don’t think gender-affirming care will be outlawed in ten days. (Mind you, I also thought the sexual abuse court decision might make people give half a shit, so what do I know?) But it does have me acutely aware: How much longer do I have? That seems to be the common question for the trans people I’ve been talking to today: How much time do I have to change my name? How soon can I scrape the money together for surgery? How much longer can I stay in the state where I’ve built my home? If this truly is the fabric of the country we live in, will the remainder of my life be measured in decades, years, or weeks?  A national monument of enduring historical significance. And a fort in the background. (Photo courtesy of Bailey Wayne Hundl) I remember the first Trump presidency. I remember how new oppressions would burst from his administration like solar flares—fast, unpredictable, deadly—and burn whichever community happened to be standing in the danger zone. And if the focus of his most recent campaign is any tell, my community’s going to need some SPF 70,000. I feel my cis friends’ knowing gloom. I get texts telling me they’re so sorry. My boyfriend holds me as he describes what he’ll do if anything happens to me. The danger is real, and I’m not the only one who knows it. There are small bright spots, electorally speaking: Zooey Zephyr, an outspoken trans state senator in Montana, won her reelection with 83%. Sarah McBride (D-Del.) will be the first openly transgender congresswoman (although she does, I’m sorry to say, support Israel’s right to “defend itself”). And I am not so naive as to pretend that amassing electoral power is enough to save my community. But it is nice to know that the next time a legislator in a room full of people suggests “hey, let’s kill the transes,” someone will be in that room to say no. But oddly enough, what brings me the most comfort is the knowledge that this country has never had my community’s interests at heart. At best, we have had the illusion of safety with some semi-significant improvements to our material realities. But I’ve always been one pickup truck of men away from becoming a headline. And before I was born, my community had it even worse. And still we loved. And still we held each other close. And still we resisted, and made art, made protest signs, made love, cried, danced, survived another day. I’m reminded so often, but especially today, of these words from queer pastor Hannah Adair Bonner: “We have never been safe, but we have always been brave. We have never been given a space; we have always had to take it.” —Bailey Wayne Hundl, content editor  “I woke up worried for my daughter.”Here are two of the things I kept in mind when I voted last week: my abortions, and my daughter.  Nona and her daughter Dorie at the Jersey Shore. (Photo courtesy of Nona Willis Aronowitz) I’ve had two abortions—one at seven weeks because I didn’t want to have a baby, and one at 14 weeks because I very much wanted to have a baby but had gotten some horrible news from our genetic screening. Both took place in New York, where they were easy to schedule, covered by insurance, and within a few miles of my house. Both times, I envisioned myself living a parallel reality of a woman in an abortion-hostile state. In 2019, when I had my first abortion, I thought about the spate of “heartbeat bills” being proposed across the country, keenly aware that my procedure would have come too late if those bills had been law. In 2024, on the eve of my second, I thought about how my devastation would be compounded by planning an out-of-state abortion without medical guidance, amid work and childcare obligations and my own deep grief. Today, 17 states would have prevented me from having my first abortion, and 19 would have blocked the second. In each case, my life would have been irreparably changed against my will. Yesterday, I hoped that the country would elect a person who believes in every pregnant person’s right to shape their fate. That did not come to pass—even though voters approved seven more ballot initiatives codifying abortion rights, all meaningful victories that reflect abortion’s broad popularity. As I cuddled my oblivious, wriggling toddler this morning, I worried for her future. But I took a teensy bit of solace in her declaration of bodily autonomy as I tried to persuade her to go potty before we left for daycare: “NO, I don’t have to go pee!!!” she screamed. It was her body; I couldn’t make her do anything she didn’t want to do. My job will be to help her keep that sense of agency, that sense of self-ownership, for as long as humanly possible. —Nona Willis Aronowitz, contributing editor  “Sit in that discomfort.”I wish I could tell you that I was shocked by the news that Donald Trump will be the next president of the United States. But I don’t want to lie. I have seen the deep ugliness, the racism, the violence of this country. I have felt the fear of living as a visibly Muslim woman, the dread of being visibly queer, and even changed the way I speak so as to make myself non-threatening to white people. I have lived my entire life under the heavy thumb of a white-nationalist America that, until 2016, went largely unnoticed by those who benefited from it. But now you see it. You see him. You know now without any doubt what has always been waiting just beneath the surface for someone willing to say all of it out loud. Someone willing to say they will reshape this nation for the benefit of white, reactionary, Christian men. And perhaps seeing it in the harsh light of day grips you with fear. For some of us, these sensations are not new. But for many of you reading this, it’s the first time you’ve seen white supremacy so naked, so unabashed. And if you are in the latter group I challenge you to sit with that fact all day today. Sit in that discomfort. Don’t look for something to point to to make all of this somehow feel okay. Spend time in the knowledge that when given the opportunity to say “no” to a fascist, a majority of Americans chose to embrace him. I’ve lived under a blanket of white supremacy for 30 years. You can endure that feeling for 24 hours. And when we are ready to resume the fight—because we are going to fight—my guiding light will be the people of the Young Lords Party of the 1960s and ‘70s who, when everything was working against them, came together to care for their own. This group of young Latine and Black activists in New York and Chicago knew politicians would not save them and so they chose each other. They chose resistance. They chose to change lives. There is nothing stopping each and every single one of us from making that same choice. This is the moment. "El machete no es solo pa' cortar caña." —Shannon Melero, newsletter editor  “We are not the lost ones.” Rebecca and her sister in community building, Caryn Rivers. (Photo courtesy of Rebecca Carroll) For those of us who voted for decency: Decency lost, but we didn’t. We are not the lost ones. We are the ones who fought and will continue to fight for each other with our whole entire selves. As a Black woman in America who is resolutely clear about the work we do and have done for this country, I’m angry AF that a white man protected by the primal callousness of America won. But I am also buoyed by the brilliant fighters who, over the last century, turned community organizing into a collective blueprint for how to be in this world. Toni told us, Jimmie warned us, Octavia predicted this almost to the letter. Our work now is to evolve the language of telling, the tenor of warning, and the vision of predicting by tapping into the reserve of love and fight and compassion created by those of us who did vote for decency. We prioritized the future safety and wellness of each other over everything else. That priority hasn’t changed. —Rebecca Carroll, editor-at-large and founding collective member  “I didn’t realize how hopeful I was.”I know we’ll have endless discussions about what happened and who to blame—a lot of which will be misguided, some of it accurate but hard to hear. I see people on social media saying they knew this would happen. I respect that, but I’m shocked at how legitimately shocked I am. I didn’t realize how hopeful I was that people would not fall for Trump’s chaos again. And it’s hard for me right now to even begin to grapple with what’s to come. But as a writer and a movement journalist, I’m clinging to one thing I know to be true: There is no greater power than of the collective and of standing with each other, and there’s never been a moment in history when that part was easy or handed to us. I’m deeply grateful for every organizer today—every person who protested, door-knocked, talked to people, made art, bore witness to atrocity, and made impossible compromises. That said, I’m not creating today. Today, I’m listening and feeling, wrapping myself in a blanket even though it’s 75 degrees in November, and eating my favorite things while the wisdom comes and the ancestors show us the way. It’s coming. Some may say it’s already here. —Samhita Mukhopadhyay, former editorial director and collective member  “It’s going to be up to them.”Waiting for the girls to wake up was the hardest part. Hearing their footsteps on the stairs, eager for news. Knowing that I’ll have to find words, again, that instill hope and protect their young spirits, but also brace them for the realities of a country and a culture that thinks of them as less than the perfect, beautiful beings they are. Words they’ll remember and return to someday when they need to draw on reserves of strength to keep going in whatever fight they will inevitably be fighting. But this time they know more. They’ve seen more. As South Asian girls, they also see themselves in Kamala — and have now watched her come so close to realizing a dream that may not arrive anytime soon. In 2016, I wrote that I found my hope in their smiles, in the light in their eyes. Today there were no smiles. Today there were tears. The only thing I could do was to look at them and tell them that I still believe. That it’s going to be up to them. That they will be the ones to lead the next generation, with kindness, with integrity, and with love. And that I will be there for them, with them, always. I’ll be fighting too. —Tara Abrahams, head of impact  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

I Was a Sexual-Assault Advocate Under Trump

Yes, it was as bad as it sounds. And no—we can’t go back

By Alisa Sieber

Imagine walking into your office every morning—a room where you’ve listened to countless survivors recount their stories, where the air is often heavy with the weight of trauma. You sit down at your desk, surrounded by the files of people who trusted you to advocate for them, only to look up and see a framed photograph of the leader of your organization—a man who was accused of sexual misconduct.

That was my reality. My commander-in-chief was Donald Trump, the man who openly boasted about grabbing women “by the pussy.” And suddenly, after January 2017, he was at the top of the military chain of command, overseeing everything including the very program where I served as a Sexual Assault Response Coordinator (SARC) in the Marine Corps.

How did I end up here, serving as a victim advocate under a president who openly bragged about violating women’s bodies?

At 17, I joined the Marine Corps on a parental waiver, seeking structure, belonging, and a way to overcome the depression and trauma I carried from past abuse. I had trusted the Corps to make me stronger than my pain, to help me become untouchable. But that trust was misplaced, and I found myself a victim of sexual assault within the organization I thought would protect me. The weight of these experiences grew heavier as I pushed myself harder, hoping the pain would fade.

Eventually, I became a C-130 pilot, flying logistical missions and supporting operations worldwide. Yet, despite my skills, I never felt I truly belonged in the cockpit. Constant pressure in a male-dominated field kept me perpetually on edge. Any sign of struggle was seen as weakness. I felt like I was breaking myself just to perform, overcompensating to hide everything I’d endured.

Midway through my career, I was assigned the role of victim advocate for the Department of Defense’s Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Program. I knew this role could trigger my own unreported trauma, but saying “no” wasn’t an option. Refusing would have disappointed my leadership, who wouldn’t have understood. And I knew survivors needed someone who truly cared, so I took the training to become a victim advocate during the 2016 election.

At that time, I never could have imagined that a perpetrator would rise to commander-in-chief. I had commissioned just as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was repealed, and combat roles had opened to all genders—a glimpse of progress. I was idealistic, believing I could help survivors find the courage to report where I hadn’t, trusting they would be supported by leaders who upheld accountability and respect.

After Trump took office, the culture shifted dramatically. Frequent policy changes and inflammatory rhetoric created tension and uncertainty within units, blurring lines around acceptable behavior. Locker room talk, inappropriate jokes, and divisive comments on gender and sexual orientation reignited divisions we thought were behind us. And my own job got harder: How could we tell survivors they mattered when the man at the top dismissed responsibility and minimized identity, service, and assault? His actions sent a clear message: integrity was no longer a priority.

For survivors like me, that shift was painful. Each day, I worked closely with other military personnel who had survived violence—accompanying them to appointments, guiding them through the judicial process, and bearing witness to their stories. The hardest moments were sitting with them as they unraveled, recounting violations committed by those they trusted—often colleagues who wore the same uniform.

In those vulnerable moments, Trump’s photograph was more than an image. It was a symbol of abandonment, a message that survivors’ pain didn’t matter. Justice felt impossible in a system that seemed to be moving backward. Survivors who dared to speak up were often ostracized, while perpetrators faced minimal consequences.

Each story weighed heavily on me, reminding me daily that the system wasn’t built to save them—or me. By 2019, I left the military, hoping civilian life would lift that burden. But the pain followed. Outside the military, I found that people didn’t want to hear about the dark realities of service or the systemic failures that harm survivors. The same people who claimed to love their country would flip their flags upside down, dismissing my nine years of service because I didn’t share their values. For believing in empathy, justice, and accountability, my experience as a Marine—my skills, my sacrifices—seemed to mean nothing. Once again, I felt silenced. And that silence is not something I want my daughters to inherit.

As I began to share my experiences, other survivors—people I never expected—started opening up to me. One of the most profound moments came recently when my own mother shared a story I had never heard before. At 18, she was drugged, assaulted, and left pregnant. Raised in a strict religious household, she couldn’t turn to her family, fearing punishment. Instead, she found support at Planned Parenthood. If not for her courage, I wouldn’t be here today.

Her story brings everything full circle—showing how bodily autonomy shapes our lives. It reinforces for me that we need leadership grounded in empathy, not just power.

The fight for survivors of military sexual trauma is far from over. With threats like Project 2025 proposing cuts to veterans’ disability benefits, survivors who serve face even greater challenges—alongside active-duty women whose health care autonomy is already limited.

We can’t allow that. I dream of a world where no survivor must live in the shadow of a predator. A world where all of us can stand openly in the light, safe and valued. And we can make that world possible when we vote.

Alisa Sieber is a Marine Corps veteran, former C-130 pilot, and Sexual Assault Response Coordinator (SARC) who served under the Trump administration. Today she is a writer and advocate, she uses her voice to shed light on the systemic challenges survivors face and the importance of leadership that truly values human dignity.

Her life-saving abortion would have been a "crime"

October 31, 2024 Happy Halloween, Meteor readers, And a happy Diwali to those celebrating, as well. I wish I had something fun and spooky to offer on this eve when the veil between worlds is thinnest, but honestly, the regular news is scary enough. So, let’s get straight into it. Maiden, mother, crone, Shannon Melero 🔮  WHAT'S GOING ON“Natural causes”: A new report from ProPublica released earlier this week investigated the preventable death of Josseli Barnica, a Texas mother who died from an infection in 2021 after doctors delayed treatment of her miscarriage. Despite the fact that doctors had confirmed that Barnica was miscarrying her 17-week-old fetus, they declined to intervene on Barnica’s behalf because it would be, as one doctor relayed to her, “a crime to give her an abortion.” Barnica was forced to spend 40 hours waiting for the fetus’ heart to stop before she delivered it shortly after. She died three days later from “sepsis due to acute bacterial endometritis…following a spontaneous abortion of a 17-week stillbirth fetus,” her autopsy shows. Underneath the cause of death, Barnica’s is listed as “natural.” Her death may have been technically natural, but it was also very much man-made. She died from negligence, from fear, and because she lived in a state with the country’s oldest abortion ban on the books. Yes, Texas’ ban has provisions that allegedly allow for an abortion to preserve the life of the mother. And yet what we have here is one more dead mother. The pile of corpses is getting higher, and still, we have to listen to pundits and Donald Trump himself pretend that these tragic stories are mere fantasy or unrelated events. Bluntly, the GOP—one of the two most powerful political parties in the country—simply does not care about preserving anyone’s life. Don’t give them the chance to do this to someone else. AND:

WEEKEND READING 📚On work: After years of dismissing the girlboss, have millennials overcorrected? Maybe, says our own Samhita Mukhopadhyay. (Bustle) On divisions: Trump’s anti-immigrant messaging is expertly designed to sow even more division between Black and Latino voters. And it’s working. (The New York Times) On deviants: “I am delighted to inform you that all monsters are gay.” (Slate)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

How Much Do You Know About Menopause?

A new documentary might teach you things about your own body that your doctor won’t.

By Vivian Manning-Schaffel

The migraines, joint pain, night sweats, and debilitating brain fog began in my mid-forties. With two young children to keep up with, there wasn’t enough coffee in the world to make me feel present. I had an inkling I might be perimenopausal, but no one—not even my OB/GYN at the time—sat me down and told me what I was experiencing was normal, let alone offered me treatment options.

I, for one, would’ve greatly appreciated if a new documentary, The M Factor: Shredding the Silence on Menopause, came out a decade ago when my hormonal shenanigans began. Produced by Tamsen Fadal and Denise Pines, it’s airing tonight, Wednesday October 17, on PBS, right in time for World Menopause Day on 10/18. It’s the first menopause film to earn medical accreditation, meaning doctors and nurses can earn credits just by watching it.

In 2025, more than 1 billion women worldwide will be in menopause, after a five-to-ten-year period of symptoms ranging from hot flashes and mood swings to vaginal dryness and heart palpitations. Yet, even though menopause is as natural as puberty or childbirth, it has long been criminally neglected, under-researched, misdiagnosed, and mistreated. Too many women aren’t properly informed before the signs kick in, are gaslit or dismissed by their doctors when said symptoms show up, and end up feeling like they’re going insane.

The documentary fills in some of these gaps, explaining what to expect when you’re done with the possibility of expecting from a medical, emotional, cultural, and historical perspective. In the absence of widespread guidance, some of the doctors featured have become revered social media heroes. For example, Dr. Lisa Mosconi, a neuroscientist and author of The Menopause Brain, discusses her important study demonstrating how estrogen connects to brain health and cognitive function because we have estrogen receptors in our brains—one of many key findings in support of Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) as the gold standard of menopause treatment.

It took a while to get to that gold standard: The documentary takes us through the devastating impact of a flawed as-hell 2002 Women's Health Initiative study falsely claiming HRT increased the risk of blood clots and breast cancer—a good section of the homogenous group of subjects were well into their seventies and could’ve been diagnosed with those conditions, anyway. Mary Jane Minkin, MD, a clinical professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Yale School of Medicine who appears in the documentary, told me when this study came out, doctors stopped prescribing HRT, and menopause education in the U.S. all but ceased. More than 20 years later, she added, a study led by a colleague of hers proved less than a third of the OB/GYN residents surveyed were taught a menopause curriculum.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RmrMwBh7l8w

Fortunately, a far more inclusive, age-appropriate, longitudinal study about women in midlife called the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation eventually disproved the WHI study, restoring the credibility of HRT. For me, it took several years of complaining, writing an article about the efficacy of HRT, and a series of tests to convince my OB/GYN to give me a prescription. Now that my sleep has largely been restored, my joints feel better, and my brain fog has immediately cleared, I mourn the years I struggled through symptoms for absolutely no reason.

The documentary takes care to note that menopause isn’t a one-size-fits-all experience. The severity and length of symptoms can vary greatly depending on who you are; they can last an average of 4.8 years for Japanese-American women and an average of 10.1 years for Black women. It also delves into the dark history of inequities of gynecology, including how Black enslaved women’s bodies were experimented upon by American gynecologists and the fact that Black women still suffer adverse outcomes and maternal mortality at disproportionately high rates.

Things seem to be slowly changing for the better: President Biden signed an executive order that allocates 12 billion dollars to women’s midlife research—something Minkin hopes will further inspire young medical students to follow in her footsteps: “I try to trick my medical students into going into menopause research because I guarantee you there’s a Nobel prize for the person who can figure this out,” she says in the documentary.

The filmmakers hope all women will learn more about menopause—even if they’re not there yet. Whether or not we eventually seek treatment for symptoms is up to us, but Sharon Malone, MD, another certified menopause practitioner, says in the doc that we may be doing our bodies a disservice by white-knuckling it. “The option should be, ‘I’m going to go, I’m going to get this addressed’ not ‘I’ll just suffer through and it’ll be over in a decade,’” she says. “You’re doing far more harm than good by just not addressing what the issues are.”

Vivian Manning-Schaffel is a journalist and essayist who covers entertainment, culture, psychology, and women’s health. Her Substack, MUTHR, FCKD, covers pop culture through a feminist Gen X lens.

New Tie, Same Old Misogyny: J. D. Vance's Failed Rebrand

By Shannon Watts

Since becoming the vice presidential nominee almost three months ago, J. D. Vance has taken almost constant fire for his long history of denigrating women, including comments on podcasts about the tragedy of remaining childless, the misery of women who work outside the home, and the duty of every post-menopausal woman to serve as stop-gap childcare for her family. As a result, Vance has the worst net favorability rating for any vice-presidential candidate in history and has become a walking meme for masculinity gone wrong.

Last night, in an attempt to shed that electoral albatross, we watched in real-time on live television as Vance attempted a calculated rebranding of himself as an ally to women everywhere.

From the glaring symbolism of Vance’s Barbiecore tie (instead of the traditional red tie Republicans typically wear) to his constant shoutouts to the women “very dear to me” (including his mother, grandmother and several anonymous women he claims to know who have been through some things), Vance worked hard to project feminine energy—someone who listens, who feels empathy, who might be open to changing his mind. But instead of embodying any of those things authentically, Vance’s debate performance came off like cosplay. This stab at a rebrand was as transparently pink-washed as his tie.

For me, Vance’s mask fell off a few times during the debate. It started when the two women moderators interrupted him for not following the agreed-upon rules, even cutting off his mic. Testy and defensive, Vance talked over them with the now-famous complaint, “The rules were that you guys weren’t going to fact check.” And even though he tried to camouflage it, Vance couldn’t disguise the misogyny that has underpinned his policy platform for decades. Moderator Margaret Brennan ended the exchange by quipping, “Thank you for explaining the legal process,” in a tone that struck a chord with every woman who has ever been mansplained to in a meeting.

When the issue of childcare came up, he implied he supported efforts to make it more affordable—even though he skipped the Senate vote for an expanded child tax credit. When abortion came up, Vance implied he didn’t support a national ban—when, in fact, he has stated publicly that he does. He told the story of a friend who needed an abortion in order to leave an abusive partner—but failed to mention the laws he supports would have instead prevented her from leaving.

But even more revealing, whenever issues like those were discussed, Vance made it clear that he sees those issues as only impacting women, as if they’re somehow untethered from any broad economic and societal implications or don’t also affect women’s partners, children, bosses, everyone. When he spoke about wanting the Republican party to become “pro-family in the fullest sense of the word,” he meant “making it easier for moms to afford to have babies.”

Even the new incarnation of Vance fails to understand that the “women’s issues” discussed during the debate are actually issues that impact everyone’s lives. The lack of high-quality, affordable childcare hurts parents, children, and employers alike. And restricting women’s rights restricts the freedom of all. We now live in a world where men are actively advocating for paid family leave and supporting abortion rights. But in his attempt to modernize his stance on these issues, Vance just wants to tell us about a woman he “knows.”

Despite Vance’s best efforts to rebrand, women wisely saw through his performance for what it was: performative. According to a CNN instant poll, after the debate Walz had the advantage among women, rising 18 points in favorability. The message is clear: We simply aren’t buying the “new and improved” Vance he’s trying to sell us.

Shannon Watts is an author, organizer, and speaker. She founded Moms Demand Action and recently organized one of the largest Zoom gatherings in history, mobilizing women voters for the 2024 Kamala Harris campaign. Her new book Fired Up is coming in 2025.

Shannon Watts is an author, organizer, and speaker. She founded Moms Demand Action and recently organized one of the largest Zoom gatherings in history, mobilizing women voters for the 2024 Kamala Harris campaign. Her new book Fired Up is coming in 2025.

Can the Taliban Be Taken to Court?

September 26, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, I’ve never been much of a space gal, (stars are for figuring out your life path, not like, science or whatever), but there is a black hole that is “spitting energy across 23 million light-years of intergalactic space.” And if that doesn’t put whatever’s happening here on Earth in perspective, I’m not sure what will. In today’s newsletter, we look at the big news out of the United Nations General Assembly, a brand-new Emmy winner, and an assault on the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act. Plus, a bit of weekend reading. Just a little speck, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON

AND:

WEEKEND READING 📚On birth: Approximately 20,000 babies have been born in Gaza in the last year. Mothers have been delivering in dangerous conditions, and “four-month-olds understand what airstrikes are.” (Marie Claire) On coming back: One of the most intellectually honest writers of our time, Ta-Nehisi Coates, has a few words for you. (Intelligencer) On selling out: Puerto Rican rappers have been surprising some of their audiences by throwing their support behind a certain orange demon. But considering the protections that proximity to whiteness brings white presenting Latine rappers, is it really all that surprising? (Refinery29)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

There Haven't Been This Many Conflicts Since WWII

September 24, 2024 Queridas lectoras, Quiero desearles a todos un feliz Mes de Herencia Hispane y Latine. Sé que somos mas que un solo idioma, pero es una de las cosas que nos unen a muchos de nosotros. Eso y tambien siglos de opresión. Un tema para un día diferente 🤷🏼♀️. In today’s newsletter, we look at the attacks in Lebanon, learn more about Project 2025’s plans for the planet, and celebrate a new world record holder. In love and Spanglish, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONOne more war: According to Vision of Humanity, there are 56 ongoing armed conflicts right now around the world—more than at any time since World War II. And over the last few days, one of them, the conflict in Lebanon, has become more deadly, with strikes from the Israeli military rattling the country. Nearly 600 people have been killed, including 50 children; nearly 2000 have been injured, and thousands more are now being displaced by violence. Israel says it is targeting the militant group Hezbollah, but the casualties are mainly civilian, and this should surprise no one—90 percent of wartime deaths are. And just as in every other zone of conflict, it is the women and children of Lebanon who will endure the brunt of Israel’s latest offensive. (If Hezbollah’s threats of revenge are to be believed, Israeli women will suffer as well.) It is an endless cycle that has claimed the lives of more than 10,000 women and children since October 7, not to mention the multitude of displaced Palestinians who will soon be joined by their Lebanese counterparts in refugee camps and asylum programs across the globe. It is untenable for Israel and its allies (like the United States) to sustain all these running conflicts, not just from an economic and political perspective, but from a human cost perspective. Women are the main drivers of most economies, but they cannot do that when they’re dead, displaced, or saddled with the disproportionate “secondary and lasting effects of war and conflict,” left behind to raise the orphans, to heal the wounded, to teach at the rubble that was once a school. Last week at Free Future 2024, Dr. Salamishah Tillet explained the paradox of expecting women to end gender-based violence this way: “Women have this unfair burden of being the primary community that's victimized and then that’s also held responsible for stopping the violence. So that paradox is impossible; it means we’re never gonna end the problem because we’re busy healing from the trauma…so if we’re going to end this epidemic, you actually need men and boys central to the movement.” She was speaking of personal assault and not war, but the analogy holds: What we all need now is for the men and boys sitting in war rooms to finally come to the decision that human lives—women’s lives—are worth the strenuous effort it takes to choose the route of diplomacy and compromise. AND:

DOWER AT THE END OF HER THRU-HIKE (VIA INSTAGRAM)

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

A Climate Story That Won't Depress You

Because that's not how Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson rolls.

BY CINDI LEIVE

Someone recently described Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson to me as a “magical human being,” which makes sense: She’s a marine biologist who somehow makes very dense climate science accessible, and she’s also a lot of fun (last week, she and actor Jason Sudeikis hosted a climate variety show at the Brooklyn Museum).

But her greatest magic trick is her optimism. In her new book, What If We Get It Right?: Visions of Climate Futures, a collection of interviews, data, poetry, and more, Dr. Johnson veers off the doom-and-gloom path of much climate coverage to go in a different direction. She talked to me by phone from near her home in Maine while a literal cricket chirped in the background.

Cindi Leive: Your title, What If We Get It Right?, implies that we can get it right—which is kind of a novel idea. So my first question is, do you really believe that?

Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: I think the most important part of the title is the question mark! [Laughs.] I think it's important to be clear that getting it right does not mean a perfect world because the climate has already changed. We're going to be experiencing climate impacts regardless of what we do. But there are a wide range of possible futures. And we basically have all the solutions we need: We know how to shift to renewable energy. We know how to improve public transit…We know how to green our buildings. It's not a big mystery what we should do.

You mentioned a wide scenario of possible futures. Can you sketch them for us?

Well, one option is the trajectory that we've been on at least until the last few years, which is just letting the fossil fuel industry win, not reining in extraction and the burning of oil and gas and coal at all, and heading toward a climate apocalypse: the mega-floods mega-droughts, mega-fires, mega-hurricanes version of the future. And that's what we get from media. That's what we get from movies. Most of the content on climate that reaches us is like, It’s a horror story, and it's only going to get worse. And yes, we do want to avoid the worst-case scenario! But if we do all of this work, what do we get? That was my impetus for the book: to show the other side if we implement all the solutions we already have. We could essentially stop the Earth from warming further. We could add many more species living on this planet with us. We could [lessen] sea-level rise. That sounds like not that big a deal, but we're talking about hundreds of millions of people—the largest human migration in history!—who might not have to migrate because of sea-level rise. So the extent to which we rein that in really matters.

I think a lot of people, when they think about preventing climate change, still think that means they have to prioritize the health and well-being of people a couple of generations from now or half the world over above their own well-being. But you don't see it that way at all.

For so long we were told that this is a problem for our grandchildren. And it's not. The dire climate impacts are already upon us. And so the thought that we could just put off action—that ship has sailed. I personally also don't see this through the frame of sacrifice. Because we are already sacrificing by not doing anything—which is a choice with incredibly horrific consequences. And so doing something is actually the easier and better option and will absolutely pay dividends.

So much of the book is deliciously nerdy—really deep in the weeds of how you make change in so many extremely specific areas. I really liked the interview with Abigail Dillen [a litigator at Earthjustice] because I don't think that people think about the courts as having that much to do with our climate futures.

We absolutely don't think about the Supreme Court generally as a big environmental issue. You know, people have been so rightly horrified by the Dobbs decision overturning Roe versus Wade. We've missed the overturning of the Chevron doctrine which gives agencies deference in sorting out the details of how to implement the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act.

We have three branches of government, and they all have a major possibility to shape, to be blunt, the future of life on Earth. The fact that the United States is the largest emitter, historically, cumulatively, is something that shouldn't be overlooked. We try to blame other countries, but it really is us. So whether we get it right really matters because we set the status quo for policy in other countries.

I also loved the chapter with Ayisha Siddiqa and Xiye Bastida. Sometimes Gen Z activism gets dismissed, like “It's all about these big theatrical gestures and made-for-TikTok protests.” But this was an incredibly intellectually rigorous chapter.

There are a lot of young people who are serious strategists and organizers working on climate, and thank goodness, because we desperately need them. This is a multi-generation-deep movement right now. The biggest thing that came out of that conversation for me was: We really need to support this next generation. Their moral clarity is a compass that we need. When they say, you're setting our future on fire, it’s true, and we need to be accountable to them.

Your last climate book was four years ago. What feels different to you now?

The policy landscape is different. Since that first book was published, we've had the Inflation Reduction Act passed, and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed, which is the largest investment in climate solutions in world history. And a lot of things are changing for the better. I have solar panels at my house because of those tax credits.

And this book is also dropping right before an election. How are you thinking about that, up and down the ballot?

First of all, this is a climate election. Who we elect will shape the trajectory of greenhouse gas emissions. We have at the presidential level, a choice between Donald Trump, who literally offered fossil fuel executives that for $1 billion in campaign donations, he would do their bidding once he got into the White House again. And then you have on the other side Vice President Harris, who was the deciding vote on the Inflation Reduction Act and signed that into law and has been there while things like the American Climate Corps were established, putting tens of thousands of young people to work on climate solutions. And down ballot, it is those local officials, the city council members. public utility commissioners, the school board, and the mayors who are deciding, do we have municipal composting? Are we expanding bike lanes and investing in public transit? Are we, you know, greening and insulating buildings and updating building codes, for example? All that sort of nitty-gritty is where change happens.

I’ve been partnering with the Environmental Voter Project, which was created on the understanding that there are about 10 million environmentalists in the US who have climate as their number one voting issue, who are already registered but who do not regularly vote. So if we can get some of those folks to head to the polls…They have a track record of shifting by percentage points the turnout in key places. If people are looking for a place to plug in before the election, I recommend that. The stakes are so high.

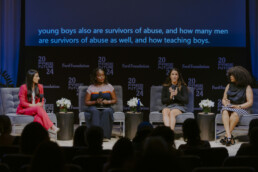

"The Women Who Have Refused to be Broken"

September 19, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, It’s been an exciting week ‘round these parts. On Tuesday, we spent the day at the Ford Foundation’s Free Future 2024: Preventing Gender Violence Around the World—hearing from incredible leaders, advocates, artists, and one highly decorated gymnast, all working toward a world in which “no one else has to say ‘me too.’ ”  L-R: SOCCER PLAYER FARKHUNDA MUHTAJ; THE HONORABLE HARRIETE CHIGGAI, WOMEN'S RIGHTS ADVISOR TO THE PRESIDENT OF KENYA; OLYMPIC GOLD MEDALIST ALY RAISMAN; AND CULTURE CRITIC SORAYA NADIA MCDONALD. (PHOTO BY MONNELLE BRITT) Every speaker brought their own lens and insight—Black Votes Matter co-founder LaTosha Brown reminded us, “There has never been a fundamental movement that has not been held nurtured and girded by…the leadership of women.” Actor and activist Danai Gurira reiterated the importance of turning our focus to the African continent to “amplify the women who have refused to be broken and see a future we all need to follow.” And in a panel on taking the toxic out of masculinity, activist David Hogg noted, “Being a man isn't defined by putting down other people—it’s defined by helping to lift others up and building community.”  L-R: FREE FUTURE HOST SARAH JONES WITH PANELISTS TARANA BURKE, AND DANAI GURIRA. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) The day ended strong with a monologue from performance artist ALOK, who shared what they would say to their younger self: “The reason that people are seeking to oppress you is not because you are weak or fragile; it’s precisely because you are powerful and tremendous.”  THE TREMENDOUS ALOK (PHOTO BY MONNELLE BRITT) If you missed the livestream of the event (cohosted by the UN Trust Fund to End Violence Against Women, the Skoll Foundation, and us), you can still catch every revelatory word from folks like Tarana Burke, Fatima Goss Graves, Padma Lakshmi, Chase Strangio, Aly Raisman, Darren Walker, and global leaders like Jaha Dukureh of the Gambia, Dr. Emma Fulu of Australia, UN Women’s Nyaradzayi Gumbonzvanda, and more, right here. And watch our Instagram for highlights. Now let’s get into some news! xx Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON

WEEKEND READING 📚On always being there: Steve Burns, the original host of Blue’s Clues, has found a new way to show up for his now adult fans. (The New York Times) On unsolved cases: There are an estimated 21,579 Latinas missing in the United States right now. And authorities have, for the most part, stopped looking for them. (Refinery29) On the “perfect vagina”: A conversation about labiaplasty on reality TV reignited harmful conversations about what a vulva should look like. TikTokers are pushing back. (Teen Vogue)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()