Mariane Pearl: Behind my ballot

Journalist Mariane Pearl can claim four nationalities—but the US is the one country she chose freely. Here’s the intensely personal story of her American vote.

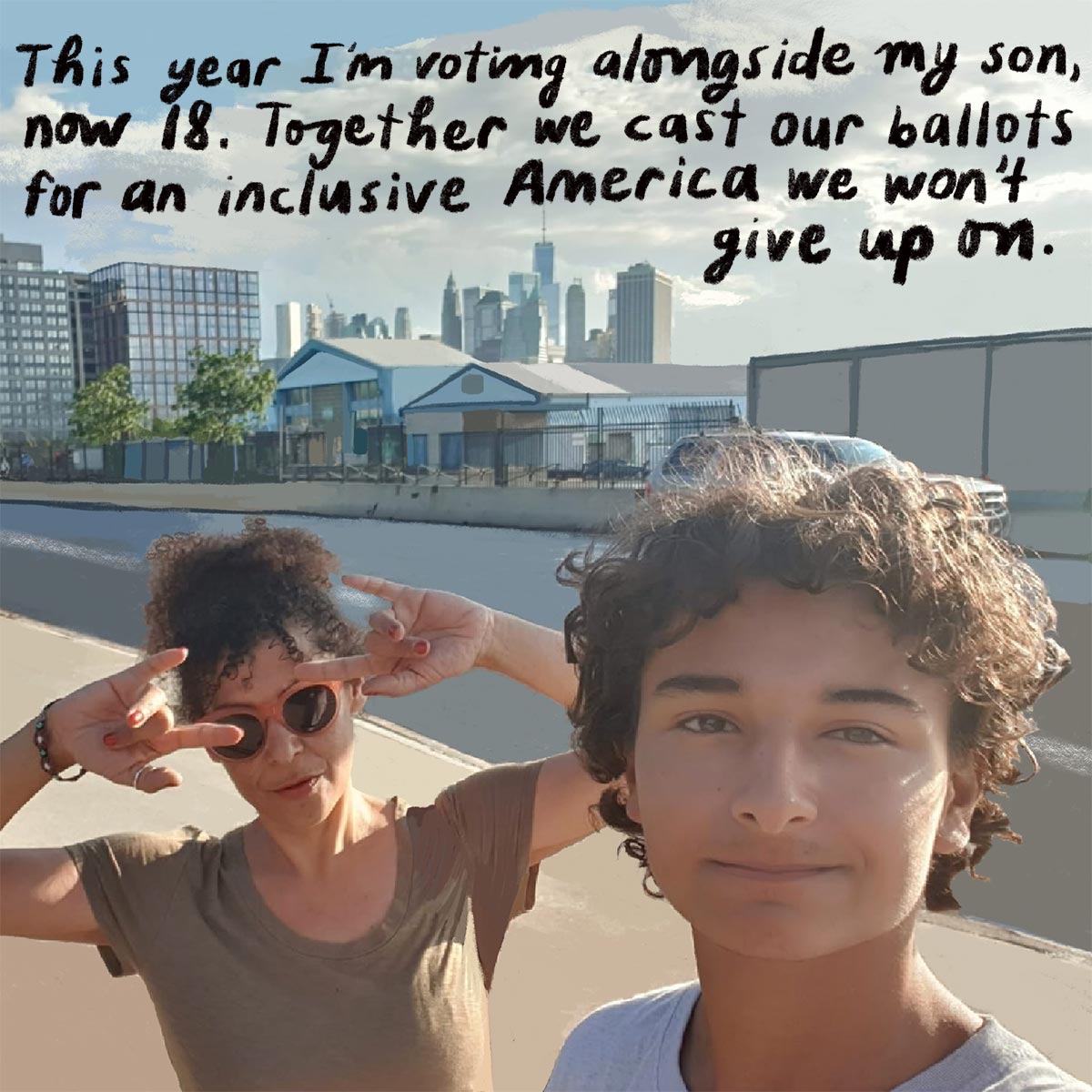

Photo illustrations by Debbie Millman

In June 2009, I was naturalized as an American. That day, on my last trip to Garden City, New York, to the now-defunct United States Citizenship and Immigration Services office, I spring-walked by billboards shooting their messages to the heavens. Becoming American felt like an accomplishment for me, a chance to review the ideals I held in a new light and commit to them. It felt like hope, a lifting in my chest, an aspiration to love a new country. This was the interview, the fifth and last test in the naturalization process. Sitting next to me were a man from India in a brown suit and a pale pink tie, and a young woman from Colombia with tiny sunsets on each of her nails. All three of us were about to become citizens of America—to raise our right hands, so help us God.

Eleven years in, it still means everything to me to be part of the only nation on earth that so thoroughly weaves all 194 other countries into its fabric. And in 2020, as I fill out my ballot from an ocean away, I feel more than ever before as if I am sending my heart by express mail.

America was the first nationality I actually chose, but it was my fourth overall. I was born in France, to a Cuban mother and Dutch father, and I look like everyone’s idea of an immigrant. Parisians take me for North African; Americans for Latina; and I certainly don’t look Dutch to the Dutch.

I realized the complexities of otherness early on. At nine, I went with my family to visit a Cuban friend of my mom’s in Algeria. I discovered then that North Africans were not only the grocery-store owners on our street, but a vast assortment of people, with languages and governments and cities. I was mesmerized and ashamed. Until then I’d been child enough to think that everyone had poor black relatives from Cuba and a rich white family from Holland. It was terrifying to realize the extent of my ignorance.

Back in France, where I was often assumed to be Arab, I sensed how tricky life was for Muslim girls there, tiptoeing their way between the expectations of dueling cultures. But when people found out I was half-Cuban, the generally hostile immigration mood turned to good-humored nostalgia. Was it true, people asked, that women who work in cigar factories roll tobacco leaves on their sweaty bare legs while listening to Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables read aloud? The sheer arbitrariness of xenophobia sent my head spinning.

At our rented flat in the XIXth arrondissement in Paris, there was a small manicured lawn outside with a few deserted benches. The grass was off limits, as were ball games, dogs, music and expressions of enthusiasm. We moved in when I was six; my father was still alive then and the flat was rented to him: a white-as-clay Dutch mathematician and Holocaust survivor with somber green eyes, a scientist who had brought a colorful family back, like pinned butterflies, from Cuba, where he’d been one of the first crew of foreigners drawn by the revolution.

By the time I knew him, my father was defeated, disillusioned by Cuba’s turn to dictatorship; he had given up hope in politics. He only emerged after dark. He liked our house motionless, undisturbed by the whistle of the dishwasher or the soundtrack of TV; my brother and I asleep and our voices quiet. And every night he turned more into a ghost, a negative version of himself. He died by suicide on a warm and lonely Sunday afternoon in Paris in August of 1976.

By the time I knew him, my father was defeated, disillusioned by Cuba’s turn to dictatorship; he had given up hope in politics. He only emerged after dark. He liked our house motionless, undisturbed by the whistle of the dishwasher or the soundtrack of TV; my brother and I asleep and our voices quiet. And every night he turned more into a ghost, a negative version of himself. He died by suicide on a warm and lonely Sunday afternoon in Paris in August of 1976.

After he died, we stayed on in that building, though on a different floor and in a smaller flat in which rent was a monthly struggle for my unemployed, widowed mother. Yet our new flat on the first floor was life itself. There was laughter and loud conversations; the light in our one-bedroom home that sometimes slept eight was the last in the building to go off at night.

Until things became more complicated. As we grew up, my brother started walking the tightrope of identity and belonging, and struggled to find himself in French society. His last name is as Dutch as it gets, but his face said North Africa. I saw him come home with his head bleeding so much he could open neither his mouth or eyes; he’d had a short conversation with two girls who happened to be dating white supremacists with bats. Or he would arrive deflated from another humiliating job interview after a man expecting an Aryan-looking candidate found my brother instead.

Before his death, my father had asked me to accomplish what he had failed at. Those were literally his words: “Promise to accomplish everything I failed at.” I was nine. The meaning eluded me at the time, and I had nothing to hold onto from him—besides my name, which I knew he had chosen for its significance: a reference to Marianne, France’s national emblem, representing democracy and resistance to oppression since the birth of the republic on July 14, 1789, when starving people had taken over the lavish kingdom. My name felt like a message from my father, and as a teen, I took it seriously, and became a secret patriot. (Secret, because everyone I knew shared a cynical distrust of anything political.) But in the privacy of my mind, I aspired to my namesake’s democratic values. In one painting by Delacroix, Marianne stands on corpses, leading the way for the insurgents, her country dress ripped off by the claws of injustice, but with her light intact. The reality of France never quite measured up, but may we French continue to search for her.

By the time I added America to my little melting pot of a life, I had married (and lost) one American, and given birth to another.

I met my husband Danny while working as a journalist in Paris at RFI, French public radio, where I was hosting a daily show called “The Magazine of Migrations.” Danny lived in London, but was reporting for The Wall Street Journal in Saudi Arabia about the plight of foreign workers there.

Among some journalists we knew, immigration and related matters were considered the worst possible beat. It meant ducking into tales of lost lives; it meant figuring out who people used to be back when they were the doctors, the nurses, the teachers, heads of their families, pillars of their nations. To me, though, the immigrants I met were modern-day adventurers (some by choice, some not), exploring the human condition. On the show, guests would share what France meant to them. Liberty, Equality and Fraternity actually had meaning to these forced travelers—these ideas meant the difference between life and death. My inner Marianne of the republic was thrilled.

When we got pregnant with our son, Danny and I were living in Mumbai, India, working as journalists. In our enthusiasm for diving into foreign cultures, we had selected a neighborhood where we were the only nonlocals. I’d been going through life as if tolerance was written in my DNA—it was not. We lived in a Jain building, which meant we were to respect every form of life as sacred. Residents walked with bare feet so as not to step on an ant. Meanwhile, right outside our flat, on the sidewalk, lived a family of six, the youngest a little girl I instantly fell in love with. The daily built-in injustice felt unacceptable to me. Every time I walked out of the house, I was forced to confront prejudices I didn’t know I had—over how we as people should live.

So in Asia, Danny and I worked hard at stretching the limits of our own minds. Danny had long asserted his worldliness by choosing a Dutch, Cuban, French, Buddhist girl as his wife. He was a Jewish kid from Los Angeles whose father was born in Israel of Polish origins and mother born in Baghdad. Adam, our son, was conceived in India and traveled to five countries before he was even born. We were in Asia, we hoped, to tell stories that could connect people and help us understand one another.

Then Danny was kidnapped and murdered by Al Qaeda terrorists—men who stood at the opposite end of the values that had cemented our relationship. Men who had trained to drain themselves of every hint of empathy and compassion. Men who kill puppies and other innocent creatures for practice. A generation of lost soldiers from discarded wars.

The night in Karachi when I realized Danny wasn’t coming home, I ran into the bedroom of the posh but soulless house where we had been staying—all beige marble and mirrors—and locked myself in to howl like a wild animal. It was almost Eid al-Fitr, the break of the Muslim holy fast, and I could hear the cries of sheep herded in the neighbors’ yards. I saw then how History leaves its deep, dirty footprint on your soul when you ignore its ripple effects.

Outside my door was an unusual mix of humankind. The people who had helped me try to save Danny were all praying for both of us. Everyone had overcome their limits to try to find him: Cops and journalists had agreed to work together; Pakistani with Americans; men with a pregnant woman. The prayers I heard that day were Jewish and Buddhist and Muslim, Catholic and secular—a litany that felt like the ultimate expression of our shared humanity.

In the days after Danny’s death, I went to visit then-President Musharraf to protect the man who had taken the most personal risks to save my husband: a Pakistani senior police officer who today is one of my son’s honorary godfathers. I listened to President Musharraf speak about how Americans were too arrogant. Then I flew to the U.S. and met with President George W. Bush, who complained to me that Pakistan was not trustworthy. Both heads of state seemingly sincere, and somewhat puzzled by the other’s behavior. I have never felt as lonely as I did that night, six months pregnant, in my hotel room in Washington, D.C.

How were they ever going to understand one another?

Only immigrants, I felt, could achieve such a miracle.

If I hadn’t been so exposed to multiple identities early in life, I might have gleefully sought comfort in hatred after Danny’s death. I understand why people find it reassuring—a single-minded story, bare and righteous, that spares us the existential angst. But blind faith in my own view was not an option for me. Our world has managed to kill hundreds of millions of its own by relying on that perspective.

My father and mother saw that firsthand. One came from the Holocaust, the other from slavery—and they’d seen in Cuba that political systems inevitably fail you. Yet they still clung to a belief in people, ordinary ones, and especially immigrants and seekers as they were. By shifting their trust from politics to the people it is supposed to guide, they saved my soul. And when I sought my U.S. citizenship, years after that meeting with the president, it was not because I believed in the American government, but because I had managed to preserve a genuine and lasting faith in its people.

I still have that faith. As citizens of a country with vastly more immigrants than any other, we Americans have a unique history: Everyone has or had relatives who remember the war, the famine, the sexual or religious persecution, the ethnic cleansing, or the promise of growth that brought their families to the U.S. So we are the good and the ugly together, the oppressors and the oppressed, the terrorists and the freedom fighters, the dreamers, the refugees and the wild west capitalists. But in the U.S. as elsewhere, blood has spilled and is still flowing—that of Native nations, of slaves then and Black people now, asphyxiated or shot to death. This year it flowed anew, with the cries of caged children, the 140-character leadership, the recurring white extremism, George, Breonna, Atatiana, Stephon. It’s for them—and for myself—that I cast my vote this time.

This fall, and as elections loom, I have found myself thinking of a story I did back when I was reporting in Paris. Danny and I had just met, and I was working in the Pigalle neighborhood, next to a small local church that looked more like a store. Home of the famous Moulin Rouge, Pigalle was a hotspot for traffickers, a place that smelled of urine and sex. Every day, I would see people coming and going to that church, a United Nations of lonely people, most ordinary, usually women. They came for Santa Rita, the patron saint of abused people, parents, widows; those who are lonely, hurt, infertile, ill. (You could see why she attracted women.)

Inside the church, the statue of Santa Rita hovered over a large polished copper bowl filled to the rim with small notes folded several times over.

“There it is,” the priest said. “The vote of the voiceless.”

You mean voice of the voiceless? I asked him.

“Actually, I mean both,” he said, smiling.

The priest read a few messages to me. Abused women who wanted out, people fighting sickness and solitude, a transgender person in search of self. The priest was right—by filling the bowl with their most intimate wish, each person was voting for survival. The unwritten stories behind their votes were there too. The perilous clandestine journeys to Europe, the hunger, the cold nights, the lines at the soup kitchen, the violence around sex, the unfathomable past traumas, the betrayals. But gathered here they found a place where someone would listen, even if just a statue. The ballots they cast were for meaning and vision; they wanted a change, and also safety, hope, and justice.

As we all do when we vote. Don’t we come to the ballot with everything we are and everything we’d rather be? With our cultures, our traumas, our aspirations, our definition of home, our understanding of how the world works and how it should be?

Where I currently live, in Barcelona, Spain—yes, another place—people are engaged in the Independence struggle and showcase their support by hanging Catalan flags, yellow with red stripes, from their balconies. I am often asked by my neighbors here which of my countries I would display if I were to choose one. To their sometime surprise, I always say America.

And so, maybe strangely, does my son. Just as my father chose my name for its symbolism, Danny chose our son’s name—Adam, like the first man, a wish for the 21st century to get its act together and allow peaceful coexistence for its global citizens.

He is now 18, and on November 3, will be working as a translator in New York for Spanish-speaking voters who look like him. And like me, he will be voting—with our shared hopes for a country we still believe in.

Photo illustrations by Debbie Millman. Debbie is a writer, designer, educator, artist, brand consultant and host of the podcast “Design Matters.” Follow her on Instagram @DebbieMillman

Mariane Pearl

Mariane Pearl is an award-winning journalist and writer who works in English, French and Spanish. She was most recently the managing editor of CHIME FOR CHANGE, and is the author of the books A Mighty Heart and In Search of Hope.