6,870 Book Bans

October 10, 2025 Happy Friday, Meteor readers, Wishing a peaceful weekend to everyone except Kacie. Girl, does the word accountability mean anything to you?  Today’s newsletter is one for the book…bans. Plus, a much-deserved just-announced Nobel winner, a new side gig for Angel Reese, and your weekend reading list.  WHAT'S GOING ONTomorrow is the last day of Banned Books Week, and man, the book banners have been going hard this year. According to the latest report from PEN America, there were over 6,000 incidents of books being banned or challenged during the 2024-2025 school year—almost three times as many as just three years ago. (No wonder Gen Z can’t read.) And the bans have implications for some students more than others: “Not all students have access to just buying books on Amazon,” PEN America’s Kasey Meehan told USA Today. “Not all students have access even to public libraries in their neighborhood that they can get to by foot or by bike or even by car.” You might assume that this rapid rush to purge schools of titles like Clockwork Orange (the most-banned book) and Breathless (number two, and a good read!) is the result of laws and White House executive orders forcing educators’ hands. But the PEN report found something even more disturbing: Schools are also removing “vast numbers” of books out of fear of getting in trouble, whether or not they are legally compelled to do so. “This functions as a form of ‘obeying in advance’ to anticipated restrictions from the state or administrative authorities, rooted in fear or simply a desire to avoid topics that might be deemed controversial,” PEN concludes. Parents and ultra-conservative groups have poured so much time and energy into filing challenges to books, in other words, that for educators, it’s sometimes easier not to have a book on shelves at all than to spend weeks fighting over whether it can stay there. And that makes the passage of actual laws requiring the removal easier. In Utah, South Carolina, and Tennessee, PEN reports an “unprecedented phenomenon” in which states as a whole are adopting “no read” lists, wherein all school districts in the state must adhere to certain books that had been flagged in multiple districts. (Sorry, Water for Elephants, that means you.). And if you’re wondering which authors get banned most, a look at the ten most-banned writers this year is revelatory: While the hyper-prolific Stephen King tops the list, he is the only white male writer; seven of the most-banned ten are women of various races, and the other two are men of color. All of which is why it’s so important to get involved with what’s going on in your community. You can support legislation that will allow libraries to carry all kinds of reading; you can buy some banned books and pass them around your neighborhood this year; and, if you’ve got time tomorrow, you can participate in Let Freedom Read Day. AND:

MACHADO EARLIER THIS YEAR AT AN ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTEST IN CARACAS. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

WEEKEND READING 📚On ignorance not being bliss: Why are so many white people shocked—shocked!—at the state of the country? (Rewire News Group) On romance: In a new memoir, Malala Yousafzai shares the story of a love that changed her life. (Vogue) On the “be yourself” trap: A new book explains how “authenticity” is often a double bind for people of color in the workplace. (The Guardian)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

An "Invasion" at Home

October 7, 2025 Salutations, Meteor readers, Spooky season is fully upon us. The apples are cidered, and the pumpkins are spiced. Delicious.  In today’s newsletter, we take a look at Operation Midway Blitz in Chicago. Plus, a new doll for the sports fans.  WHAT'S GOING ONDespite objections and a lawsuit from the state of Illinois, Trump has deployed the National Guard to Chicago to augment ICE agents and detention facilities across the state. Governor JB Pritzker released a statement saying, “We must now start calling this what it is: Trump’s invasion.” Perhaps it seems like an overstatement to refer to the increased presence of federal agents and the National Guard as an invasion, but let’s look at the facts. Last month, the Department of Homeland Security initiated something called Operation Midway Blitz, which was designed to “target the criminal illegal aliens who flocked to Chicago and Illinois.” DHS claims this operation was driven by the death of a young Illinois resident, Katie Abraham, who was killed in a drunk driving incident in which the driver was an immigrant. So what’s come of it? Well, in the 30 days that Midway Blitz has been active, Block Club Chicago reports that ICE officers have shot two people, tear-gassed protestors, detained children and a journalist, choked a man, and shot a chemical agent into a reporter’s car—all under the guise of protecting U.S. citizens from immigrants. When pressed about children who had been detained and zip-tied, Russell Hott, the field director overseeing Midway Blitz, said, “Children have been encountered pursuant to arrests for targets. In those instances, there have been parents that wanted to bring their children with them, and we have accommodated that.” That so-called accommodation happened during an overnight raid at a South Shore apartment complex last week, where children were removed from their homes in the middle of the night, and 37 people were taken into custody. Chicagoans have been protesting Midway Blitz at every opportunity, which is why, according to Trump’s logic, the National Guard had to be brought in. But these moves aren’t just meant to instill fear into immigrants—they’re also meant to aggravate and worsen existing divisions in Black and Latine communities, which, despite having linked struggles in the United States, have often been at odds due to the racialization of different Latine groups, anti-Blackness, and political manipulation. When ICE agents pursued and choked a man in East Garfield Park last Wednesday, witnesses allegedly shouted at the officers, “He’s not Mexican, he’s Black,” in order to get them to stop harassing the man. These divisions are not a secret to the administration; they know we cannot fight them if we are busy fighting each other. But worsening immigration raids are not simply a “Latino issue” or a Mexican issue; they are a problem for everyone who doesn’t fit the ideal of what an American looks like—yes, that means anyone not white or white-presenting. Anti-immigration policy is, at its most basic level, rooted in racism, and that has never been clearer than it is now. The Trump administration does not want brown, Black, Asian, Chicano, or any other type of people living in the United States (Trump does want white South Africans, though), and Trump is using every tool available to him to make this country in his own crusty caucasian image. So once again, it is on We the People to do the work ourselves. We aren’t going to solve intraracial relations overnight, nor will we pretend they don’t exist. What we can do is recognize that our survival as people of various groups is inextricably linked.  AND:

THE NEW DOLLS ARE MODELED AFTER ELLIE KILDUNNE, ILONA MAHER, NASSIRA KONDE, AND PORTIA WOODMAN-WCKLIFFE. (VIA MATTEL)

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Good Abortion News Still Exists

October 3, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, You already know what I’ve been thinking about all day:  In today’s newsletter, we tip our hats to the advocates doing the darn thing in South Carolina. Plus, an American cheese queen and your weekend reading list. Love ya, mean it, bye, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONPushback in South Carolina: On Wednesday, an all-male committee held a public hearing on South Carolina’s SB 323, the most draconian and vile proposed abortion ban in the country (and that’s saying a lot). The men of the Senate Medical Affairs Committee were joined by so many advocates and protestors that they needed two overflow rooms to hold everyone. All in all, the committee listened to more than seven hours of testimony from those who supported the ban and those who opposed it, including Tori Nardone of South Carolina’s Women’s Rights and Empowerment Network, who spoke with The Meteor earlier this week. Even some anti-abortion groups joined the opposition, claiming the bill goes too far and would be harmful to pregnant women. That’s how extreme this bill is! So what happens next? After this week’s hearing, the committee will meet again privately to discuss next steps on this bill. A vote hasn't been scheduled, and there is a strong chance that it will not survive the regular legislative session, which begins in January. Hope is alive! The FDA, doing its job: Speaking of hope: Hours before the government shutdown on Tuesday, the FDA approved a generic version of the abortion pill mifepristone. (Quick point of clarity here: Mifeprex, which received FDA approval in 2000, is the “brand” name, while mifepristone is the drug itself.) This is actually the second mifepristone generic to be approved by the FDA, following GenBioPro in 2019. The irony here is, of course, that both of these moves occurred during Trump’s time in office—and they are both instances in which a government agency actually functioned as intended, since legally the FDA must approve a generic if the manufacturer can prove it’s identical to the branded version. Evita Solutions, makers of the new generic, applied for approval in 2021, and following an extensive review period, the FDA found that the drug is “bioequivalent and therapeutically equivalent” to Mifeprex and therefore safe to be used as an abortifacient. But in contrast to the 2019 approval, the MAGA faithful are furious that the FDA would do something as heinous as…carry out the tasks and responsibilities assigned to it in compliance with the law. How dare they! AND:

PHEE ISN'T HERE FOR THE FOOLISHNESS, CATHY! (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

WEEKEND READING 📚On (show)girlhood: What do Taylor Swift and Shakespeare’s Ophelia have in common? They’re both whatever we want them to be. (Teen Vogue) On Mother Benson: Why are we all still so obsessed with Captain Olivia Benson, arguably the only good police officer in the NYPD? (Dame Magazine) On rebuilding: A year after Hurricane Helene devastated entire counties and much of the Appalachian Trail, conservationists are still working to repair it. (National Parks Traveler) On looking back: Palestinian journalist and new memoirist Plestia Alaqad, 23, sometimes can’t believe the things she’s survived. (Teen Vogue)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

An Abortion Ban That's "Just So Vile"

October 1, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, Eight years ago this week, the world watched as Carmen Yulín Cruz Soto, then the mayor of San Juan, Puerto Rico, stood in front of a room full of reporters and pleaded for help in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. “We are dying, and you are killing us with inefficiency,” she said, referring to President Trump and FEMA. With tears in her eyes and defiance in her voice that day, Cruz Soto added, “We will make it with or without you.” It was a moment that will stay with me forever—the moment it became crystal clear how little the United States cared about the people it had worked so hard to colonize. For some time, it felt as if all the world saw when it looked at Puerto Rico was a land perpetually recovering from a hurricane. But after millions of records sold and an historic residency in El Choli, Bad Bunny has brought the eyes of the world to Puerto Rico not for her despair but for her art, music, culture, and history. So on Sunday, when it was announced that he would be headlining the next Super Bowl, it felt like an enormous middle finger to the colonizers. And when he hits that stage, it will be with our flag and our music. On February 8, millions will watch what journalist Susanne Ramirez de Arellano describes as “a Puerto Rican singing in Spanish on the most precious stage of the colonizers.” I think it will be the sweetest sound I ever hear.  READY YOUR PLENA DRESSES FOR FEBRUARY SISTREN. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) But until the blessed day is upon us, let’s see what else is going on in the world. First, we head to South Carolina to understand a “nightmare” abortion bill. Then a quick flight to New York, where Mattie Kahn introduces us to an unexpected RHONY candidate. Shannon Melero PS: The Meteor will be closed on Thursday for Yom Kippur, so we will see you all on Friday when we’re back.  WHAT'S GOING ONThe very worst ban: One of the most extreme abortion bans in the country has its first hearing tomorrow in the South Carolina statehouse, where lawmakers and civilians will have a chance to show support or opposition for Senate Bill 323—a bill so vile that Tori Nardone, the communications manager for Women’s Rights Empowerment Network (WREN), tells The Meteor that “it cannot be allowed to move another inch.”. What makes SB 323 unique among other abortion bans in the U.S.? “It’s a bill that would treat abortion essentially as a homocide,” Nardone says. It would do so by re-labeling embryos as persons under the law, a change that would enable the criminalization of anyone who destroys an embryo, whether they’re a medical provider or a pregnant person. (Currently, no other state criminalizes pregnant people for having abortions, but providers and manufacturers have come under fire.) “This bill doesn't just limit abortion,” Nardone explains. “It threatens contraception, IVF, miscarriage care, and even free speech.” Under SB 323, anyone sharing information on how to obtain an abortion, even one outside the state of South Carolina, could be held criminally liable. “IVF often involves creating multiple embryos, some of which may not be implanted, so redefining embryos as full legal persons could criminalize very standard IVF procedures that people need and want to grow their families,” Nardone says. The bill would also ban medication abortion, remove exceptions for incest and rape, create a gag order on sharing abortion information, and establish a bounty hunter law by which individuals can sue anyone who may have helped someone get an abortion. To put it in the simplest terms: imagine if the most extreme part of every existing abortion ban was stitched together to make a Frankenstein’s monster of bans. That is SB 323. Tomorrow’s hearing in the statehouse is scheduled outside of the regular legislative session— a sign that the South Carolina GOP is eager to put it on a national stage, which Nardone says is detrimental to women everywhere. “Passing this bill would set a very dangerous precedent for other states to follow,” Nardone says.“This isn’t just a South Carolina problem,...This is a national issue.” Nardone herself has volunteered to speak tomorrow at the state house, where she will tell her own personal story of seeking abortion care, and she hopes that the hundreds of others who have volunteered to speak will illustrate the severity of this bill. As Nardone puts it: “It’s just so vile.” As always, now is the time to make noise. Call your senators, email them, email their assistants, and their assistants’ assistants. There is still time to ensure that this bill never makes it to a first round of voting.  MEANWHILE IN NEW YORK...New York City Mayor Eric Adams has announced that he is dropping his bid for re-election, ending his lackluster campaign for a second term. Now he did have to go. His poll numbers had sunk to new lows, he had been charged in a federal corruption case (later dropped), scandal had engulfed his administration, and he has lied about—among other things—the actual value of his rental income, his experiences with a neighbor’s dog, and being vegan. These are bad qualities in an elected official, from whom we should expect ethical leadership and transparent accounting. But—and please hear me out—these are great qualities in a Real Housewife of New York! As he contemplates life after Gracie Mansion, I’d like to encourage Eric Adams to pursue a new sphere of influence: The Bravoverse.  ADAMS, ALREADY MAKING FRIENDS WITH HIS POTENTIAL FUTURE CO-WORKERS, REAL HOUSEWIVES OF NEW JERSEY STARS JOE AND MELISSA GORGA. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Let’s consider the evidence: Like some of our best Housewives, Adams has a nice smile, is defensive and self-interested, and loves a good time. I do not trust him to balance a budget or build affordable housing, but I know he could plan a fabulous girls’ trip (just think of the perks that must come with his status on Turkish Airlines). This man looks at home in a sprinter van. He holds an endless number of grudges. He believes in ghosts. And at least 30% of what comes out of his mouth in public could double as an iconic tagline. See: “My haters become my waiters when I sit down at the table of success.” Or: “Lions don’t lose sleep over the opinions of sheep.” Ramona Singer wishes! Our own Shannon Melero offers the perfect tag line: “I ran New York… I know when I smell a rat.” New Yorkers believe in second chances. For Eric Adams, atrocious leader, redemption is possible! All he needs is to host a rat-themed season finale gala. Andy Cohen, call him! — Mattie Kahn  AND:

THE LIBRARY IS OPEN!! (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

The ICE Stories We Don't See on Camera

September 25, 2025 Greetings Meteor readers, It’s been a very long week, but a delightful one in my life as one of my closest friends just had her first child (and no, I’m not talking about everyone’s bestie Rihanna).  BADGALRIRI BUT MAKE IT MINI (SCREENSHOT VIA INSTAGRAM) In today’s newsletter, we consider the lives lost in ICE custody. Plus, we commemorate the 30th anniversary of the historic United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. Baby C’s auntie, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONYesterday, a young man opened fire across from an ICE detention facility in Dallas, Texas, killing one detainee and critically injuring two others before taking his own life, the AP reports. Little is known about the shooter and his motivations, but the Trump administration is already making early claims that this was an ideologically motivated killing based on writings allegedly tied to the shooter, and ammunition found at the scene that read “ANTI-ICE.” This is an ongoing investigation, and as details unfold, we will hopefully know and understand more. But something we know right at this moment is that, even prior to this shooting, 19 people have died in ICE custody this year. That’s 19 human beings—some possibly dead as a result of human rights violations while in federal custody. It is an ongoing tragedy, and perhaps what makes it even more tragic is that it is mostly going unnoticed. The actual taking of humans into ICE custody has stirred attention and outrage. Videos of immigrants and legal citizens across the country being snatched off the streets have gone viral; each time, we are angry, and we question why federal agents are wearing masks. But then what? For the most part, what happens to detained people next takes place with little media attention, except in a few cases that manage to hold the national attention, albeit briefly. But overall, ICE detainees are being disappeared and, now, 20 of them have disappeared permanently. Twenty lives may seem like a negligible number, especially with 58,000 individuals currently being held in detention centers around the country. But each one of them matters—to their families and to us. And when we go about our days as normal and no outcry accompanies these deaths, the administration gets the message that Americans are willing to tolerate at least this level of violence. What else might they do, counting on our silence? To find out what to do if you see ICE agents in your neighborhood, check out this comprehensive explainer from The Intercept. AND:

“A revolution has begun. There is no going back.”On the anniversary of the Beijing women’s conference, a blueprint for a brighter future ONE OF THE OPENING DAY SESSIONS FOR BEIJING (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Thirty years ago this month, women from around the world gathered for a conference that made history and, as it turned out, would not happen again. The 1995 UN Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing was a monumental moment for activists and world leaders who came together to “answer the call of billions of women who have lived, and of billions of women who will live,” as the first female Prime Minister of Norway, Gro Harlem Brundtland, put it at the time. It’s the meeting at which then-First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, building on years of women’s organizing, famously said, “Women’s rights are human rights,” which made global news because it was (and apparently remains) a radical perspective. The journey to the conference—which is documented in a new multimedia project from the United Nations Foundation and co-produced by The Meteor—was two decades long, with previous meetings held in Mexico City, Copenhagen, and Nairobi. Beijing itself was the largest women’s rights gathering at that point in history, with a massive audience of 45,000 people invested in building a better future. Pulling it off was no small task, but the leaders charged with doing so were more than up to it. Among them was the inimitable Gertrude Mongella of Tanzania, the Secretary-General of the conference, who later became known as Mama Beijing. “A revolution has begun,” she said during a closing speech at the Conference, “there is no going back.” Mongella was a key player in producing the Beijing conference’s most significant document: The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action—which remains the most comprehensive blueprint for gender equality and women’s rights ever created. It wasn’t just a wish list; 189 countries committed to it in Beijing. It demanded women’s inclusion in government and policymaking; economic policies built with gender in mind; the understanding that violence against women is a human rights violation; and was also one of the first international agreements to demand that governments complete a thorough analysis of how climate change and industrialization had affected women. From the Platform: “The continuing environmental degradation that affects all human lives has often a more direct impact on women…Those most affected are rural and Indigenous women, whose livelihood and daily subsistence depends directly on sustainable ecosystems.” You probably know how this ends: While some of the Platform’s key goals have been achieved—women’s representation in government, for instance, has risen—many have yet to be fulfilled, 30 years later, not because of an absence of activism, but because of global backlash and competing priorities. But the women at the forefront of global change remain motivated. When asked what the next global feminist conference should focus on, Nyasha Musandu of the Alliance for Feminist Movements put it this way: “We must dare to dream bigger, disrupt deeper, and build bridges across movements. The fight for justice is not just about breaking barriers—it’s about reimagining the world itself.”  WEEKEND READING 📚🎧On the business of babies 🎧: Kindbody was poised to be a “disruptor” in the fertility industry. Was the human cost worth it? (IVF Disrupted) On your problematic friends: Emma Watson is still trying to grapple with her relationship to anti-trans author J.K. Rowling. (The Cut) On the shoulders of wives: There is one thing that makes it a little easier to drive a country toward fascism: a complicit housewife. (The Guardian)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

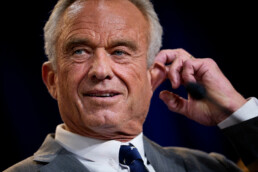

Does RFK Jr. Know the Scientific Method?

September 22, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, We are closed tomorrow in observance of Rosh Hashanah, but we couldn’t let you go into the week without your favorite newsletter! But before we take a little rest, let’s talk about Tylenol. Raw dogging our headaches, Shannon and Mattie  WHAT'S GOING ONFor the past two weeks, news has been swirling that the Department of Health and Human Services is expected to announce a potential link between pregnant people’s use of Tylenol and a supposed increased risk of autism in children. Those reports intensified over the weekend, and senior officials are now briefing media outlets on background. The timing makes perfect sense for exactly one person and no one else: That would be HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Yes, the same man who is imperiling millions of children with his documented anti-vaccine agenda and has admitted to having a literal brain worm. Several months ago, he said that he intended to find the root causes of autism before the end of September. With October on the horizon, he must be feeling the pressure. So here we are. The expected new guidance—which is expected to drop before the end of the week—will tell pregnant women not to use Tylenol except in cases of high fevers, robbing them of one of the few options they have to manage pain for the 40 weeks they spend growing another human. (Doctors have long recommended Tylenol, the name brand for the generic acetaminophen, because similar fever reducers and pain relievers like Ibuprofen, the generic drug behind Advil, have a documented association with miscarriage and potential fetal harm.) The obvious question, of course: Is Tylenol dangerous? While some limited research has suggested a possible association between Tylenol consumption and autism, larger studies—including a recent and major examination of the outcomes of 2.5 million children in Sweden—have turned up no connection. And the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recently affirmed the recommendation of Tylenol in a recent statement to CBS News, telling the outlet that “there is no clear evidence that proves a direct relationship between the prudent use of acetaminophen during pregnancy and fetal developmental issues.” The prevalence of autism has increased over the past 25 years, according to CDC statistics, with a range of possible explanations. One that we know to be true is that the definition for what constitutes the condition has changed and expanded, making it easier to be diagnosed (and to access services). What we also know to be true? The drug Tylenol has been available over the counter for almost 70 years—well before the documented growth in cases. So scientists, researchers, and those who can count agree: Tylenol is not the likeliest culprit for the increase in autism rates. They reach that conclusion via the scientific method, which isn’t just a unit in high school curricula. It’s an actual process that actual scientists respect. It involves investigating observable phenomena through rigorous testing and careful experimentation. It does not involve setting self-imposed deadlines and drumming up questionable research to meet them. But there is no doubt that this announcement will confuse pregnant women, their providers, and their families. It will, in all likelihood, make those who are experiencing pain while pregnant (that’s 100% of pregnant people, FYI) hesitate before treating it, wondering if their degree of discomfort justifies a dose of relief. (Even though we know that stress and pain can themselves lead to adverse outcomes for babies, including preterm birth, low birth weight, high blood pressure, and other complications.) This announcement will not make pregnant women or children safer or healthier, but it will sow more doubt in the medical establishment, and it will make women suffer. — Mattie Kahn AND:

I BELIEVE THIS IS WHAT THE YOUNG PEOPLE CALL AURA. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

This Email is Censored

September 18, 2025 Hey there, Meteor readers, I’d love to say something fun and clever here, but apparently, saying too much can cost you your job, so 🤐. In today’s newsletter, we don’t mention a single controversial or emotionally charged topic, and we definitely aren’t talking about censorship, conditions in ICE detention centers, or reproductive rights. In fact, if any spies are here, we’re actually just discussing... some popular films today. So, ya know, nothing to see or report on here. Protecting the bag, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONIt is so incredibly difficult to keep up with everything going on when it feels like everything is going on at the same time. But if the GOP can stage a multi-pronged attack on free speech, reproductive rights, and literal science all at once, then we do need to figure out how to walk and chew gum at the same time. So what exactly is happening with reproductive rights while we’re all distracted by what one is or is not allowed to say about a murdered white supremacist? We wouldn’t know. We’re just here to be chill and discuss some really interesting films: A Quiet Place: A recent study from the Electronic Frontier Foundation found a “social media censorship crisis” in which platforms like Meta, TikTok, and even LinkedIn are blocking users from viewing posts that contain information about abortion. EFF found that in the case of Meta, the company has been removing posts, claiming they violated the community terms that prevent users from buying, selling, or trading pharmaceutical drugs. But the posts reviewed by EFF “very clearly did no such thing.” Thankfully, EFF put together some helpful guidance to help keep the free flow of abortion information going (without sacrificing your privacy). Shadow Force: The Cut’s Andrea González-Ramírez spoke to a midwife caring for women in ICE detention. The suffering these women endure—sitting in a detention center where they were placed by a self-described “pro-life” government—is so horrendous and potentially triggering, we won’t repeat it here. But this reporting is a reminder that reproductive justice is inclusive of so many issues, immigration rights among them. Warfare: Anti-abortion states are bending over backwards to limit access to abortion pills, even going so far as to classify mifepristone as a Schedule IV controlled substance, putting it in the same category as Xanax, Klonopin, and Valium. To be clear, this doesn’t make mifepristone illegal, but it does make it more difficult to obtain, even though mifepristone is just as safe as penicillin and Viagra. Thunderbolts*: This is actually a positive update highlighted by our pals at Autonomy News. States like New York and California are strengthening their shield laws to protect abortion providers and doctors offering gender-affirming care. Good things are still possible when we keep vigilant and pressure our elected officials to keep abortion accessible everywhere. AND:

PRECIOUS BIG BABY BEAR (SCREENSHOT VIA EXPLORE.ORG)

WEEKEND READING 📚(Home) On the range: More women in the U.S. are getting into ranching than in previous years. Yee hawt or yee nawt? (The Guardian) On well-hidden extremism: Trad-wives started out as a content category, but author Cynthia Miller-Idriss explains how the once innocuous lifestyle trend morphed into something more nefarious. (Teen Vogue) On a musical comeback: Bomba y plena never went away, but it’s seeing a resurgence among young people. (Remezcla)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

A Moment for Trey Reed

September 16, 2025 Evening, Meteor readers, Today, my good friend of over a decade put her first children’s book out into the world. Happy pub day to Everything Grows in Jiddo’s Garden, and three cheers to my favorite Jersey girl who never backs down. In today’s newsletter, we try to understand a horrific incident in Mississippi. Plus, a call for retribution from the vice president and a new rookie of the year. (Yes, we know, the news is an emotional rollercoaster.) Surviving, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONOn Monday morning, the body of Demartravion “Trey” Reed, a 21-year-old Black man, was retrieved by local police in Cleveland, Mississippi. And by retrieved we mean: They pulled his body down from the tree where it had been hanging on the Delta State University campus. During a press conference, the university police chief told reporters that there was “no evidence of foul play,” but that an investigation was still underway. Naturally, people are skeptical of the findings, with many posting a single, resounding phrase across social media: “Black people don’t lynch themselves.” This isn’t the first case of a suspected lynching in the last year. In June, Earl Smith (58) was found hanging in Albany, New York. Last September, Dennoriss Richardson (39) was found hanging in Sheffield, Alabama. And in March, twin brothers Qaadir and Naazir Lewis (19) were found in Hiawassee, Georgia, with gunshot wounds to their heads. Each of these deaths was ruled a suicide, but in Richardson’s case, there were conflicting autopsy reports. In Smith’s case, members of the community accused the local police of not conducting a thorough investigation. In the Lewis case, both the NAACP and the Lewis family rejected the findings based on where the boys’ bodies were found. In a perfect world, we wouldn’t have to question police findings, but that world has yet to be discovered. In this world, we know that Black men are not afforded the same level of justice or care as their white counterparts. We also know that, statistically, Black people have lower suicide rates than all but two other racial groups. It may be months or even years before we know the full truth of what happened to Demartravion Reed and those who have died in a similar fashion. So all we can do is work with the truth that is currently available to us, which is that Black bodies are under threat. Historically. Recently. Daily. This very minute. When these deaths happen and go widely unnoticed and underinvestigated, we as a society perpetuate that threat, allowing for greater loss and greater silence. So until we have all the answers, do not let Trey Reed’s name go unspoken. AND:

BEAUTIFUL INSIDE AND OUT. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

We Didn't Want to Write This

September 11, 2025 Good evening, Meteor readers, Last night, I held my daughter a little longer than usual, to which she said, “Get off, mama.” But I clung to her tiny frame like a life raft. When the days are particularly dark and the rhetoric unbearable, sometimes the only thing that feels manageable is a hug. It is a crushing weight to try to prepare my daughter for a world so violent, so numb to the murder of children, so uncaring to little brown girls that look like her. There is a lot to be said about the shooting of Charlie Kirk yesterday, and certainly in the days to come, you’ll hear it. Some of it you may agree with, some will challenge your way of thinking, and some will be nonsense. But people will talk about him. They will remember him. They will memorialize him. They will reference him in the ongoing conversations about gun policy and political violence. And they will forget the everyday people who have been gunned down in the streets walking to work, walking to school. Going home. Those murders are political too. They matter. They are an eternal reminder that America values the right to own a gun over the right to live safely. So today my heart is with every person who continues to ask why wasn’t my child’s murder enough to change everything. Why didn’t they care when it was one of us? In community, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONRinse, repeat: It was another horrific, predictable Wednesday in America. How so? Well, there were two school shootings, although most headlines were accorded to one of them. The first was captured in a gruesome video that went viral and looped over and over in the social media feeds of most people I know, who had not intended or wanted to view an assassination on X. (We will not be linking to a murder clip here.) It also unfolded at the exact moment that its target—the MAGA political activist Charlie Kirk—was answering a question about gun violence in America while visiting Utah Valley University. The other shooting took place at Evergreen High School in Evergreen, Colorado, where the gunman died of self-inflicted injuries and two students were wounded. One of them remains in critical condition at a local hospital. President Trump—a close confidante of Charlie Kirk’s and the beneficiary of Kirk’s alarmingly successful crusade to convert college-aged men in particular to the Republican cause—ordered flags be flown at half-staff.  (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Good. Lower the flags, not for Kirk, but for the rest of us, who are grieving what has been made normal here. It is tragic that we live in a place where one school shooting interrupts another. It is unspeakable that an eighth grader at Evergreen told local news he’d just moved to the area a few months ago and didn’t think “this would happen so soon.” So soon. It is insane, not normal, diseased. We should be tearing our clothes. We should be in mourning over the decisions that have brought us here. The flags should be at half-staff until something changes. But of course, the people with the power to do that—the people lowering the flags, the people calling for a moment of silence on the House floor—are the same people who could pass legislation literally today to mitigate this. These people could make it harder to get a souped-up hunting rifle so that what happened to Charlie Kirk doesn’t happen to their colleagues or their children or our colleagues or our children. You should know: Utah, where Charlie Kirk was killed, voted to relax gun laws on college campuses just a few months ago. In August, KSL NewsRadio published a headline that reads: “Students and Faculty at University of Utah Can Now Open Carry with a Permit.” It was an astounding, sickening day. It was just another afternoon in this heartbreaking country. — Mattie Kahn AND:

Oh, and the Emmys Are Still HappeningBY REBECCA CARROLL  SIRI, PLAY ALL OF THE LIGHTS (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Yep, the world is burning, but Hollywood is still giving out little gold statuettes to the kids at the popular table. And this year’s Emmys, which air this Sunday, actually feel important, especially as the Trump administration continues to make drastic cuts to and place restrictions on funding for the arts and creative institutions. So if giving out awards at a sparkly, red-carpet event reminds us of how important the arts are in this particular moment, I’m all in. Also, who am I kidding? I’m always all in. I live for an awards show. I’m going to limit my predictions to the main categories, and rate accordingly. Best DramaShould win: The Pitt, because despite its clear echoes of ER, it’s got a heart of gold, resurrected the career of Noah Wyle (one of our last good white men standing), and features a truly inclusive and diverse cast of characters who are all fully developed and nuanced. Will win: Severance, because it's the best show in this category. There’s literally nothing wrong with it—it’s stylistically vivid, flawlessly written, and ingeniously cast. Personal fave: Paradise. While the apocalyptic premise of Paradise is, in turns, cheesy and terrifying, Sterling K. Brown—along with a very solid supporting cast, which includes the excellent James Marsden and Julianne Nicholson—grabs us in the gut from episode one, and after that, it’s just impossible to look away. Best ComedyShould win: The Studio should win because it’s a bold, original, and cringeworthy send-up of Hollywood sent from the actual heavens. It took me a few episodes to get into it, but then I realized that the key to enjoying this show is to give in to the cringe and let go of the silly notion that people in Hollywood are just like us. They’re not. They’re a different breed, and I love that for them. Personal fave: Only Murders in the Building. Selena Gomez, Martin Short, and Steve Martin walk into a building—I mean, the rest writes itself. Will win: The Studio, if only because Hollywood wants us to think that it's self-aware. Best Limited SeriesShould, and will, win: Adolescence is my fave and will win. It deserves to win because, for starters, each of the four episodes in the series was shot in one take. That’s not only unheard of, but also logistically challenging. And yet each presents as seamless. And then, with that in mind, the chemistry between the actors feels so organic, it’s almost uncomfortable to watch. That’s good TV.  ONE OF THE LAST GOOD WHITE MEN NOT NAMED PAUL RUDD. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Best Actor, DramaShould win: Sterling K. Brown (Paradise) should win and is also my fave, because he carries a frame with such heft and dedication. You can see his artistry at work, while also believing that he is wholly the character he’s depicting. That’s what acting your ass off looks like. Will win: Adam Scott (Severance), and that is absolutely fine, because he makes a nonsensical character make perfect sense. Best Actress, DramaShould win: Britt Lower (Severance) should win, and is also my fave. The red hair, the simultaneously robotic and fluid movement of her body, the blue pencil skirt, the Mensa IQ-level vibe—it’s all riveting. Will win: Kathy Bates (Matlock) and listen, if I am in the new prime of my career at 77, then praise be.  THE WINNER IN OUR HEARTS (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Best Actor, Comedy SeriesShould win: Seth Rogen (The Studio) should and will win. I came late to the Rogen party. I always found him kind of dopey and disconsolate. But then I realized that his talent as an actor is his precision at playing dopey and disconsolate. He’s also fantastic in the highly underrated Platonic, with the true gem of an actress, Rose Byrne, and that gives him added appeal. Personal fave: My forever fave is Martin Short. I have loved him since I was a teenager, watching him on Saturday Night Live. He is brilliant, a consummate performer, and one of the funniest people on the planet. He manages to make the fairly repetitive nature of Only Murders in the Building (I mean, maybe move out if everyone’s getting murdered?) feel fresh every season. Best Actress, Comedy SeriesShould win: Jean Smart should and will win. Smart, who, like Deborah Vance, the character she plays on Hacks, has been in the business for decades, brings a kind of sad, driven beauty to the role that might otherwise elude a less seasoned actress. You hate Deborah, then root for her, and then ultimately, you just feel for her. Also, Designing Women anyone? IYKYK. Personal fave: My fave is Ayo Edebiri (The Bear), because her kind of funny is subtle and intellectual and Black and authentic. It’s a killer combo that I’ve not really seen in the latest crop of actors. Best Actor, Limited SeriesShould win, personal fave, and will win: Stephen Graham (Adolescence) should win, is my fave, and will win, because Holy God, he is just so good in this series. As the father of a boy who may or may not have committed murder, Graham is utterly saturated with palpable grief over his failed self-expectations as a parent. It’s a raw, quiet, beautiful, and devastating performance. Best Actress, Limited SeriesShould win: Cate Blanchett (Disclaimer) should win, because she never gets it wrong. I’m not even a massive fan: I find her slightly precious in interviews, but ever since I first saw her in the 1997 Gillian Armstrong film Oscar and Lucinda, I have found her to be so elegantly reliable as an actress. And in Disclaimer, as a journalist with a dark secret potentially about to be revealed, she pivots from fear to rage to vulnerability with the ease of a dancer. Will win, and personal fave: Michelle Williams (Dying for Sex) will win and is my fave, because she has something special. In her 2017 Oscar-winning performance in Manchester By the Sea, she managed to embody what it looks like to keep functioning when the small lives that came from her body are dead. As Molly, in Dying for Sex, she taps that same artery of despair while continuing to breathe in full, deep breaths.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

SCOTUS Rules in Favor of Racial Profiling in Los Angeles

September 10, 2025 Howdy, Meteor readers, Apparently, today is National Hot Flash Day. So sorry I didn’t get anyone a gift, but you know, the holidays sneak up on you!  In today’s newsletter, we pull back the curtain on the Supreme Court’s latest decision. Plus, good news for parents in New Mexico and a chat about Tylenol. Hot every day, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONSomething old, something new: On Monday, the Supreme Court overturned a lower-court order that had temporarily blocked federal agents from stopping people in Los Angeles to ask them about their citizenship status based on race or ethnicity; whether someone speaks in Spanish or with an accent; and their location or profession, the New York Times reports. This means that, for the time being, anyone in LA who looks like they may be from another country can be stopped, questioned, and temporarily detained by a DHS officer without probable cause other than the color of their skin. All of this probably sounds vaguely familiar to you. Stop and frisk. Broken windows policing. Jim Crow. The Geary Act. All policies—from the 2000s, the ‘90s, and the late 1800s—that reflected this prejudiced thinking. In her dissent of the Court’s ruling, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, writes, “The Constitution does not permit the creation of such a second-class citizenship status.” (It once did—but that’s why we have amendments, at least on paper.) However, in practice, the U.S. has had a long-standing relationship with racial profiling, discrimination, and the silent assertion of a second class—it is possibly the most American characteristic there is. But something about how it’s being deployed here feels a bit different. Perhaps it’s how quickly it all seems to be happening, or the violent, militarized nature of it; there is something new in this old practice.  DEMONSTRATORS GATHERED NEAR GRANT PARK IN CHICAGO TO PROTEST DONALD TRUMP'S IMMIGRATION POLICIES. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) “The Court’s order is troubling for another reason,” Sotomayor continues. “It is entirely unexplained.” The Supreme Court justices who issued the majority judgment gave no reasoning for why they overturned the original lower court order. (Meanwhile, Sotomayor’s dissent is 21 pages.) Perhaps that’s what feels novel: the blatant shamelessness with which discrimination is now enacted, despite all of our progress as a nation. There was a time when men convened in secret to plan and execute hateful acts. Now, extremists stroll through the White House in broad daylight, gleefully carrying out a supremacist agenda with the support of American voters. And not having to feel bad about it just fuels their now-unabashed ambition. So much so that the modern GOP is quite literally defending enslavement and trying to reshape how children learn America’s complete and despicable history. You know what they say, those who can’t remember the past… AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()