Before You Post That MLK Quote

|

Hey there, Meteor readers, I didn’t make a lot of resolutions for 2023. I’m about to have a child, and I hear they really derail any and all of your plans. But one thing that was on my goal list was to find a daily affirmation to carry throughout the year—and by George, I think I’ve done it. On Tuesday, the love of my life, Michelle Yeoh, told an entire orchestra, “I can beat you up, okay? And that’s serious,” when it tried to interrupt her length-appropriate acceptance speech for Best Actress at the Golden Globes. This is the energy I want to maintain for the rest of the year—whatever comes at me, whether it be a minor inconvenience or an entire Hollywood orchestra, I can beat it up. And that’s serious!  In today’s newsletter, we revisit the words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.—and not just the ones you already know. Instead, Meteor editor-at-large Rebecca Carroll takes a closer look at King’s writing, and how it moves her today. But before that, a touch of news. Channeling Michelle, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON“Compromising” on abortion: Virginia Republicans have introduced what they’re calling a “moderate” and “reasonable” abortion bill that would criminalize abortion after 15 weeks in that state. But as we used to say at my old job, the proof is in the paperwork; what’s being touted and what’s actually written in the bill are two entirely different things. Slate’s Mark Joseph Stern points out that, among many other glaring issues, this bill criminalizes abortion before viability can be determined—meaning if a patient discovers at 17 weeks that their fetus cannot survive outside the womb, they are legally obligated to carry that pregnancy to term unless it will literally kill them. And even the exception for the life of the pregnant person is written in such a way as to discourage doctors from performing life-saving procedures. Stern writes that while the bill would allow doctors to do an emergency abortion after 15 weeks, using their medical judgment they are, “subject to incarceration if prosecutors disagree with their assessment and a jury determines that the abortion was unnecessary.” This isn’t much more moderate than the Texas abortion ban that led to Amanda Zurawski nearly dying of sepsis because her doctors were legally unable to act quickly enough. Stern writes that many patients have been “forced to the brink of death” because there are so many medical issues that can “harm pregnant patients without guaranteeing their death.” And under H.B. 2278, doctors have no choice but to wait until death is imminent. What an interesting way to approach law making from the party that claims to value life the most. AND:

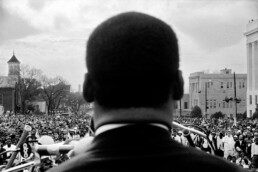

EXAMINING A LEGACYWhen Dr. King Talks to Me, This is What He SaysA reflection on the words you know and the ones you don't. BY REBECCA CARROLL  DR. KING ADDRESSING A CROWD IN ALABAMA. (IMAGE BY STEPHEN SOMERSTEIN VIA GETTY IMAGES) I grew up in New Hampshire, which was the last state in the country to observe Martin Luther King, Jr. Day as a holiday (kicking and screaming, at that; they held out until literally the year 2000, almost two decades after federal legislation making it a national holiday was passed). At home, though, my white adoptive parents told me the words and leadership of Martin Luther King, Jr. made them feel encouraged about adopting and raising a Black child. “We believed in his message about people of all races coming together,” my mom liked to say. To which I responded, on more occasions than I’d like to recount, that first of all, it was a dream. People of all races weren’t exactly unified when King made his “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963—the year Medgar Evers was murdered, the KKK killed four little Black girls at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, and tens of thousands of folks marched on Washington for their basic civil rights. And second of all: He was killed because of that dream. My parents’ interpretation of King’s message felt willfully naive to me. But it is not uncommon for white liberals then or now to pride themselves on just knowing who he is while conveniently forgetting how radical his message was at the time of his assassination—particularly following his public denouncement of the Vietnam War in a speech given at the Riverside Church in Manhattan. Up to that point in 1967, most Northern liberals felt pretty OK about supporting King’s fight for civil rights on American soil. But when it came to people of all races in other parts of the world? Not so much. (King also committed the cardinal sin of pushing back against American military power, considered unpatriotic then and now.) The media went nuts. In a piece called “Dr. King’s Error,” The New York Times, a notable ally of King’s, called his speech “both wasteful and self-defeating.”  DR. KING BEING RUSHED BY A MOB OF PROTESTORS WHO WERE FOR THE VIETNAM. (IMAGE BY JACK SHEAHAN VIA GETTY IMAGES) But his words, the famous and less-famous ones, continue to exist and reverberate in the world. It’s odd to miss people you’ve never met (much less public figures or historical icons) but when I reread some of King’s words, I miss him. I miss the extraordinary power and passion of his focus and his love for us in real time. I often wonder if he could have imagined how the things he said amid great struggle and duress would decades later be cut, spliced, removed from their context, and posted on Instagram. I wonder if he could guess that there would be a generation that knows him better for his quotes than for the fact that he helped get a law passed authorizing the federal government to treat me—and people of all races—equally. If we are going to keep lionizing his quotes, though, then MLK Day (now recognized nationally) is a good time to look at a few of them more closely and reconsider the ways they still hold meaning. Here are a few that resonate with me:

The strident clamor of the bad people still be stridently clamoring. (Two words for you: January 6th.) And as we face some of the most vicious attacks on our rights, the “appalling silence of the good people” continues to damage and divide us as a nation. The U.S. Supreme Court eliminated the constitutional right to abortion. There were over 600 mass shootings documented in 2022. Voter suppression is still rampant. And while I am heartened by those who do speak out and protest, most people, even those who consider themselves fair-minded, choose to remain silent. That astonishes me.

Still holds. I don’t think even the most well-intentioned white people understand that America’s default settings—the standards of all that we know and have codified into the canons of literature, beauty, education, moral codes, and societal behavior—is a made-up truth devised to make non-white people, specifically Black people, feel less than across the board.

In other words, your acts of oppression are oppressing us both.

Will it, though? I wrestle with this line of Dr. King’s. I have committed myself to the struggle throughout my entire life and career—and it doesn’t always feel noble. A lot of times, it just feels exhausting. King was not wrong about the struggle making you a better person, but being a better person doesn’t automatically mean the world changes. That’s the throughline—for all of King’s grace, fortitude, and elegant militance, he placed his faith in a universal humanity that did not exist then and does not exist now. But I suspect King knew that as well. If America could have its own version of humanity, then why couldn’t he have one, too? One that doesn’t demolish the other version, but rather helps to rehabilitate it? As his daughter Bernice King has reminded us in her own tireless efforts at carrying on King’s legacy: “My father literally fought his entire life to ensure the inclusion of all people because he understood that we were intertwined and connected together in humanity.” I guess that’s ultimately what keeps me in the struggle: a version of humanity that is fueled by compassion and sustained by the truth of our existence. And I will chase down that version until it no longer needs to be imagined. As King himself said, “We must accept finite disappointment, but never lose infinite hope.”  JOIN US!It’s been six months since the Supreme Court of the United States overturned Roe v. Wade. We are living through a once-in-a-generation moment around reproductive freedom. So where do we go next in 2023, particularly when we know that it will be birthing people of color who will experience the most harm in this moment? On Wednesday, January 18th–just ahead of what would have been the 50th anniversary of Roe v. Wade—The Meteor will host Roe At 50: Abortion Access From Now On. This virtual briefing will feature a conversation with Renee Bracey Sherman, founder & executive director of We Testify and co-author of the forthcoming book, Countering Abortionsplaining; and Brittany Packnett Cunningham, award-winning activist and the host of UNDISTRACTED; moderated by Regina Mahone, senior editor at The Nation and co-author of Countering Abortionsplaining. To learn more and register for this FREE virtual event, click the button below.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Iran Will Execute More Protestors

|

Top of the evenin’ to ya, Meteor readers, I am in a mildly jovial mood as I write this because this newsletter is our 100th edition. Can you believe it? It feels like just minutes ago we were deconstructing Pam and Tommy and wondering what might happen if Elon really did buy Twitter. Simpler times, no?  In today’s centenary newsletter, we return our attention to Iran, which slipped from headlines while Kevin McCarthy and his drama were sucking up all the air in the room. Plus some other news you might have missed. For the (literal) hundredth time, let’s get into it. With an attitude of gratitude, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONExecutions in Iran: As protests continue, day-by-day conditions are worsening for those fighting for freedom. Four men were executed by the state after being arrested at protests, and 12 more have been sentenced to death. Their crimes? “Waging war on God,” or in layman’s terms, going against a theocratic government that runs on willful and violent misinterpretations of religion. At present, the total number of Iranians sentenced to death is believed to be 41 (but could be higher). While most of those sentenced to death have been men, women also continue to suffer under the regime’s crackdowns on protestors, facing arrests and both physical and sexual violence. According to WIRED, the Iranian government is also able to use facial recognition software to identify anyone breaking hijab laws. These protests are no longer focused only on the death of Mahsa Amini and the unequal treatment of women. Several Iranians who spoke to The Washington Post anonymously explained that they are fighting for “cultural and political freedom” for all and against the “economic mismanagement” of the current regime. One man, whose family was priced out of Tehran, told the Post, “I feel rage, rage and a lack of hope. It’s desperation…If we go out to protest, they crack down in the worst and most reprehensible way. We really don’t know what to do. We can’t protest. We can’t improve our situation.” As outsiders, we’re seeing the ingredients come together for a slow-moving, long-lasting, and life-altering revolution: Political unrest, economic distress, and religious contention all crashing up against each other until, eventually, the people become too powerful to contain. But this shift in power won’t happen overnight. As journalist Neda Semnani wrote in a previous newsletter, “We must acknowledge that in order for this revolution to succeed, many brilliant, beautiful, and brave human beings will give up their futures for someone else’s. We must acknowledge their suffering, their fears, and most of all, the lives they won’t get to live. We must also acknowledge the people they leave behind and the pain those who will survive will carry with them. This is what it means to resist and to revolt. It means that one group will sacrifice their plans, their potential, and all their normal mornings so that perhaps, one day soon, the rest of us might revel in freedom.” AND:

The United States has the shortest paid parental leave policy of any wealthy nation in the world, with a whopping ZERO weeks of guaranteed paid leave for workers. FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays. Ideas? Feedback? Requests? Tell us what you think at [email protected]

|

![]()

Why the Congressional Sh*tshow Matters

|

Hey there, Meteor readers, The first week of January is almost over; how are those resolutions coming along? Yeah. Mine too. Tomorrow, as we all know, is the two-year anniversary of the January 6 insurrection. I can’t remember what I had for breakfast this morning, but I can still remember that day when someone told me there was a riot at the Capitol and I simply responded, “No, there’s not.” A few moments later we were watching it unfold on CNN: thousands of people violently rushing into the Capitol building demanding that Mike Pence and Congress reject the results of the 2020 election. Jan. 6 was a turning point in American history and politics. A group of people had a completely different understanding than most of the country of how democracy should work and they were being goaded on by a sitting President. Alarmingly, not much has changed to ensure something like this can’t happen again. Yes, arrests were made and prison sentences were handed down to rioters—but election deniers still hold positions of power. More than ever ran for office in 2022 (though many lost). Donald Trump, who reveled in the event, still talks about a presidential run despite the January 6 Committee recommending he face criminal charges. We are truly in the Upside Down. In today’s newsletter, we get into this year’s big mess, Kevin McCarthy, the latest on Andrew Tate, and a touching note from one of you. (If you’ve never sent us a message, try doing something new this year!) Wondering how two years went by so fast, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONDon’t speak: It’s been a bad week for Representative Kevin McCarthy, who lost ten different rounds of voting in his attempt to become Speaker of the House. The fact that his own party is responsible for making McCarthy a national embarrassment is the kind of true-life comedy Judd Apatow wishes he could write. But beyond the extremely good tweets this event has produced (including this IG post) lies a more serious problem. The 118th Congress can’t be sworn in until a Speaker has been chosen, which means that because of this right-wing nonsense, the country has been running without a functional House all week (although how functional it’ll be when this all gets sorted is a question for another day). So while we’re all enjoying a hearty laugh over this man’s desperation to get some votes (and some pizza), let’s not forget we need this matter to be resolved to get on with the work of governing. As Amanda Marcotte explained in Salon, it’s not really about McCarthy: “It's about the Republican Party's self-conception in its exciting new fascist iteration (which was forged under Donald Trump but doesn't really have much to do with him either).” In order for fascism to flourish, Republicans must, Marcotte writes, “bully” and “ritually purge a once-trusted insider” who’s failed to fall in line with the group. What will the GOP choose? Implosion or compromise? My money’s on the former.  WHEN THE JOKE'S NOT THAT FUNNY BUT YOU KNOW THERE'S ANOTHER VOTE COMING. (IMAGE BY CHIP SOMODEVILLA VIA GETTY IMAGES) More than words: During a televised conference on state-run IRNA news, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei of Iran made a comment about hijab that we’re extremely skeptical about: “Hijab is undoubtedly an inviolable necessity, but this inviolable necessity should not cause those who do not fully observe hijab to be accused of being irreligious or counter-revolutionary,” he said to a room full of women. The comment was an attempt, after four months of protests over the death of Mahsa Amini, to hint at some sort of directional shift or leniency on the government’s treatment of those not observing their interpretation of hijab. But given that the same government has handed down 26 death sentences for those who have been arrested at the protests, it’s not particularly inspiring anyone to believe that change is on the way. It gets worse: Two women have come forward against influencer Andrew Tate claiming they were abused by him in the UK in 2015 and their cases were allegedly mishandled by UK police and Crown Prosecution who failed to bring any formal charges against Tate. (Not only was he not prosecuted, he was on Big Brother UK during the investigation.) According to Vice, Tate was arrested on suspicion of sexual assault and physical abuse and was eventually released while the investigation into the women’s claims took four years to be handed over to CPS. During that time, Tate was allegedly running a “webcam sex business” with his brother. AND:

OPENING OUR INBOXThis week we got an absolute gem of a letter from newsletter reader Sean who writes: Let me first start by stating that my 24-year-old daughter is amazing!! I want her life to have an equal opportunity for happiness, health, career satisfaction, respect, and choice for her future life decisions. She is the reason I started reading your articles. In fact, she is the reason I’m able to love without boundaries. I believe that these freedoms dictate the ability to truly express love. And I don’t want a world where authentic love is stifled. I want love to abound....I want the most authentic love attainable for me, and all others. This defines a healthy world. Commonality is found across the globe (based on this). I commend your education, to men like me, through thoughtful articles. Sean, we’re so happy that you’ve found your way to us. And aren’t you a lucky guy for having an amazing daughter. Thanks so much for reading!  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays. Ideas? Feedback? Requests? Tell us what you think at [email protected]

|

![]()

We're Getting In on the In/Out Trend Too

|

Felicitous new year, Meteor readers, Wow, we’re back at it again in 2023. I, for one, have been in a time freeze since the last time we chatted. The Meteor is coming off of a seven-day vacation during which I chose to live my best life—and by that, I mean I reorganized my closet and played several hours of God of War: Ragnarok. (She’s a gam3rgrl.) I hope your end-of-year was just as exciting.  In today’s newsletter, we’re easing ourselves into 2023 with our own version of what’s in and what is absolutely out (*cough* low-rise jeans *cough*). But first, let’s take a look at the news. Typing from the floor of my extremely clean closet, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONBirth behind bars: According to the Arizona Republic, Perryville prison induced three incarcerated women before their due dates without their consent. While induction is safe in most cases, doing so before a due date is a decision between a patient and a care provider—and the women told reporters that they were not given the choice to refuse induction, and would have preferred to give birth without it. They’ve also claimed that prison medical providers insisted that the inductions were part of Arizona Department of Corrections policy—most likely as a way to decrease the prison’s liability—rather than a medical necessity, bringing an entirely new and frightening meaning to forced birth. (The ADOC did not comment on the situation, but NaphCare, the medical contractor working with the prison, denied the existence of any such policy.) One of the women, Stephanie Pearson, told the Republic, “They just told me that someone on a different yard a few years ago went into labor in their cell, and had their baby in the cell, and that's why they induce everyone now.” Desiree Romero, who was also induced, said she wasn’t surprised that she wasn’t being given any choices: “I’m quite used to the prison making all these decisions for us because we are still state property.” AND:

MARTINA PRESENTING THE WOMEN'S SINGLES CHAMPIONSHIP TROPHY AT LAST YEAR'S US OPEN. (IMAGE BY DIEGO SUOTO VIA GETTY IMAGES)

THE LAST IN/OUT LIST YOU'LL NEED THIS YEAR You know what's always in? Winning free stuff. We're giving away tote bags to the first 10 people to click on the image below just as a thank you for sticking with us into the new year.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays. Ideas? Feedback? Requests? Tell us what you think at [email protected]

|

![]()

Your Favorite Meteor Stories of 2022

Happy (almost) New Year, dear Meteor reader,

It’s almost our anniversary—yours and ours. In January, Meteor founding member Jennifer Finney Boylan wrote the first feature essay of the Meteornewsletter—and it’s been a thrilling journey ever since. So much has happened this year, and who better to celebrate with than you?

First, a round of applause to Meteor collective members who had astounding years. There were books: Supreme Court commentator Dahlia Lithwick released her much-anticipated Lady Justice; Amber Tamblyn’s Listening in the Dark taught us to trust our intuition; and Julissa Natzely Arce Raya’s latest, You Sound Like a White Girl, acted like medicine unto the bones.

And there were prizes: Rebecca Carroll snagged three Webbys for her show “Billie Was a Black Woman,” Salamishah Tillet won a Pulitzer for distinguished criticism, Dawn Porter showcased the heroes of Title IX, and our podcast “Because of Anita” got a Gracie. It’s giving…

Meanwhile, in a year that came with some challenges, it meant a lot to us to tell stories that resonated with you on the issues that matter. Projects like the “My Abortion Story” series, the viral Josh and Amanda Zurawski interview, Talia Kantor Lieber’s student investigation into colleges paying (or not paying) for abortion travel, and live events like 22 For ‘22 and Meet the Moment where we got to meet some of you, in the flesh, for the first time.

It was also an emotional year on our podcast “UNDISTRACTED” with some amazing episodes: the most important conversation about RENAISSANCEever, an analysis of the Great Resignation with Elaine Welteroth, and who could forget the touching dialogue between host Brittany Packnett Cunningham and her husband, Reginald, about the birth of their son, who was delivered at just 24 weeks. Some of us are still crying about that one. (It’s me, I’m us.)

Of course, I would be remiss if I didn’t shout out the highlights of my favorite part of The Meteorverse: this newsletter right here, powered by all of you. Thank you, readers, for every open, every click, and every time you’ve forwarded our stories to someone you know. It means the world to us. And if you are so inclined to continue sharing The Meteor with your friends, family, enemies, exes—anyone you want, we don’t judge!—here’s a list of our top 10 newsletters this year as decided by you, the all-powerful arbiters of interesting.

10. Muslims Are Not a Monolith

9. “If they could kill her, they could kill anyone.”

8. Queen Elizabeth’s Complicated Legacy

7. How Our Data Is Used Against Us in the Post-Roe World

6. The Best (and worst) Parts of the KBJ Hearings So Far

5. The Supposed Death of #MeToo

4. When “Feminists” Spout Hate

2. Puerto Rico’s Dimming Future

The entire Meteor team wishes you a gentle and restful new year. We’ll see you here, in your inbox, in 2023. And we’ll keep bringing you the news and stories you want to know about with a full serving of feminist perspective—and a splash of dry wit—to keep things interesting.

For auld lang syne,

Shannon Melero

What We Can Do for Abortion in 2023

|

Dear Meteor readers, I’ve officially started the process of shutting down my brain (watching Emily in Paris; let me live) and getting ready to unplug for the rest of the year. I hope you’re doing the same. But before we enter the land of holiday snacks and midday naps, we have a few more really special sends for you. Today, my colleague Cindi Leive writes about abortion—what she’s learned from years of covering it and how not to repeat the mistakes of the past. But first, a little news—about Ukraine, lady governors, and menopause visibility. Merry merry, Samhita Mukhopadhyay  WHAT'S GOING ONHistoric visit: If you haven’t yet, it’s worth reading/listening to the powerful, funny, and historic plea President Volodymyr Zelensky made before Congress yesterday. Our own teammate Anya Kurkina, whose family is in Kyiv, told us, “As a Ukrainian living in the US, I felt an immense sense of pride watching Zelensky address the nation. He holds the weight of world peace on his shoulders, and we are determined to stand behind him and the European people every inch of the battlefield. Peace will have to be won. He understands the value and the price of it.” New cruelty in Afghanistan: The Taliban has officially banned women from attending university. There had already been a ban on teen girls attending high school, but this new announcement will deny those who have already graduated access to higher education. This move is devastating to Afghan women, who said they were shocked by the decision. AND:

EDITOR'S NOTEBOOKThe Abortion Stories I Wish I’d ToldOur personal experiences matter, but the media (including us!) owes patients moreBY CINDI LEIVE  A PORTLAND PROTESTOR SAYS IT ALL ON JUNE 24, 2022. (SOURCE: GETTY IMAGES) It’s been 181 long days since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. And every morning, you probably pick up your phone to learn a horrific new consequence of that decision: bleeding patients turned away from hospitals, pregnant people prosecuted, doctors told by lawyers that they cannot do their jobs. Abortion is everywhere now. Not the procedure—that’s been around for 4,000 years—but the subject, which has re-entered public discussion after several decades of euphemisms and stigma. (All it took was an apocalypse.) As someone who worked through a lot of those silent, euphemistic years, I’m wowed daily by the commitment and resourcefulness of the journalists on this beat, along with the patients telling their own stories under the toughest circumstances. All of which has made me reflect on my own coverage of abortion—and how to do it better. A little personal history: When I first started in women's magazines in the 1990s, few major outlets covered abortion. (The publications of the 1980s had done so more openly—it was on the cover of People in 1985!—but by the ‘90s, the self-proclaimed “pro-life” movement had begun its ascent, and the assumption that abortion was distasteful and divisive settled in.) I was lucky enough to work for a boss who felt differently. When state legislatures began to pass bills requiring teenage girls to get permission from their parents—or a judge—in order to end a pregnancy, I walked into an editorial meeting, voice shaking, and pitched a story on the laws; she green-lit it—unusual at that time—and we went on to do a series that exposed the rising shortage of doctors willing to do abortions at all. Over the years that followed, I was proud of the stories the teams I led did—and generally confident that sharing the truths of what pregnant people experience would prompt progress to roll forward, and minds to change. By the time I got around to writing about my own abortion (emboldened by many who’d shouted before me), TRAP laws and doctor assassinations were putting more and more providers out of business; the Hyde amendment had made abortion difficult-to-impossible for low-income women. (All while Roe still stood!) But I still held out hope, on some level, that personal stories mattered. Wouldn’t it make a difference, I wrote, if the people who wanted to deny us our freedom had to look us in the eye?  PROTESTORS IN DETROIT, JUNE 24, 2022 (PHOTO BY EMILY ELCONIN/GETTY IMAGES) Well…maybe. Since then—and especially since Texas’s SB8 went into effect last fall—personal abortion stories have come fast and furious. On talk shows and the floor of Congress, in Sunday sermons and YouTube testimonials, in amicus briefs, and the set of SNL, people who’ve chosen abortion have shared their experiences with mounting urgency and the frustration that comes from feeling like no one cares. In the years that come, those stories are going to be especially important, and some will be devastating. But what do we (meaning the media, The Meteor included) owe the people who tell these stories? And now that everyone’s talking about abortion, how can we talk about it better than we used to?

TOTAL ACCURATE AND INACCURATE ABORTION-RELATED STATEMENTS PER CABLE NEWS NETWORK, AS OF FEBRUARY 8, 2019 (SOURCE: MEDIA MATTERS FOR AMERICA)

Finally, and most importantly: It’s not just about abortion. During my decade and a half as the editor of Glamour, we published plenty of abortion stories I was proud of—how it felt to have one, to self-manage one, to jump through legal hoops to get one. But in 2010, the GOP weaponized gerrymandering to rewrite the makeup of key legislatures; pretty sure we never covered it. In 2013, the Supreme Court green-lit voter suppression with its historically awful Shelby County v. Holder decision; again, we never covered it. Obviously, we should have—for a million reasons, but partly because the political machinery the right put in place over that decade laid the groundwork for our current abortion hellscape. Many of the trigger bans which snapped into cruel effect after Dobbs were in states like Ohio, Missouri, and Georgia, where the majority of people favor legal abortion, but ruthless gerrymandering or voter suppression meant it just didn’t matter. We were telling stories, but not the whole story. The story of abortion is fundamentally not just a story about bodily autonomy and why crusty white men should have any say about whatever’s in your uterus. (Although, let’s be clear, they should not.) It’s a story about why our country still accepts that presidents who lose the popular vote can nominate justices who are confirmed by a Senate which radically over-represents white, agrarian states and that those justices then can green-light laws passed by state governments which no longer represent the will of their people. It’s a story about misogyny, yes, but it’s also about the malapportionment of the Senate—even though those words are really hard to make appealing in a Good Morning America segment. (Only Stacey Abrams can do that).  STACEY ABRAMS SPEAKS ABOUT THE GEORGIA ABORTION BAN JULY 20, 2022 (SOURCE: GETTY IMAGES) A few days after Roe fell, I interviewed Dahlia Lithwick, and her words rang in my head for months. That very first week, "I had a pollster say to me, ‘Dahlia, women just don’t care about structural democracy reform," she said. "And my answer was kind of like, well, then prepare to keep losing, 'cause we can’t fix this with marching and tote bags." And she’s right: As Black women organizers have been saying for a century, voting rights underpin all other freedoms, and abortion is no exception. Though it may sound impossibly optimistic, I believe we are going to win on abortion, at least eventually and at least technically. There are too many of us, there will be too many horror stories, and the punishment for politicians, even in this messed-up democracy, is already evident. Securing reproductive freedom might take years and would be heroic. But if we only attend to abortion and not the larger landscape that permitted the laws against it to thrive—the same landscape that enables laws against LGBTQ populations, poor people, immigrants, and gun reform—we will be back, Whack-a-Mole style, to attend to the next issue, and the next, and the next.  Cindi Leive is the co-founder of The Meteor, the former editor-in-chief of Glamour and Self, and the author or producer of best-selling books including Together We Rise. Her related reading recommendation: This CJR piece; it's excellent.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

There's Another Report on the Widespread Abuses in Women's Soccer

|

Hey Meteor readers, I’m peeved this evening. I’ve been peeved all day, really. This morning, a new report detailing ongoing abuse in women’s soccer was released and I’ve been muttering obscenities under my breath about it all day. So as you can guess, we spend some time with what’s in it and what’s being done about it. We’ve also got a quick cruise through today’s news. Let’s get into it. Staring out the window, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONContinued abuse in women’s soccer: A new joint investigation conducted by the National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) and the NWSL Player’s Association confirmed widespread “sexual abuse, unwanted sexual advances…emotional abuse, cronyism, racist remarks” and retaliation against players who reported this behavior. If you’re wondering why this sounds so familiar, it’s because the Yates report, released in October of this year, arrived at a similar conclusion. The new report examines the league as a whole and provides more detail on specific misconduct allegations, including those levied against former Gotham FC general manager Alyse LaHue, who was fired in 2021 to the surprise of team supporters. (LaHue was presented as the woman who would turn Gotham, the New Jersey area team, around.) According to the unnamed player who made the allegations, not only did LaHue engage in sexual harassment, but she also practiced religious discrimination. LaHue’s lawyers deny the allegations. The report also detailed the fallout from an incident that took place last year involving the Houston Dash’s Sarah Gorden. After a match in Chicago, Gorden had shared on Twitter that she and her boyfriend had been racially profiled by security staff. No disciplinary action was taken—but even more alarmingly, this latest report reveals that head coach James Clarkson asked Gorden’s teammates to apologize to the security staff for publicly supporting her claim. Clarkson even went so far as to hand out the phone numbers of the accused so that players could easily contact them. But even with these two bombshell reports, there might be more to uncover. Both U.S. Soccer and some NWSL teams “delayed providing key evidence,” citing legal privilege due to “confidentiality or non-disparagement agreements with coaches fired for misconduct.” Additionally, both reports make it a point to get at the larger issues at play: The NWSL didn’t have an anti-fraternization policy until 2018, which could have curbed the number of coaches who felt emboldened to pursue players romantically—nor was there an anti-harassment policy until 2021. (If you’re keeping track, that’s 30 years after Anita Hill and four years after #MeToo!) That means there was no structure for players on reporting or handling unwanted advances from coaches or other team staff. Instead, most accused coaches were quietly fired or transferred to different teams within the league to continue their careers undisturbed, as was explained both in the Yates report and this one. While the entire report is infuriating, one section, in particular, made me want to yeet my computer into the Passaic. On top of having to deal with harassment, job insecurity, and retaliation, many players reported being treated like “charity cases” rather than professional athletes. Imagine for a moment spending your entire adolescent life training for a job, getting scholarships for your talent, eventually being signed to a professional team, being harassed and silenced in an effort to keep your job only to have the owner of that team act as if they’re doing you a favor. One unnamed player explained, “[The owner] made it seem like his players were his kids which, if you had the owner of the Knicks saying that to one of his players, that’s weird.” Two investigations into rampant, widespread abuse, and all anyone has to show for it are some lukewarm apologies and belated recommendations on strengthening a one-year-old anti-harassment policy and adding in sensitivity training? We need to do better.  AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays. Ideas? Feedback? Requests? Tell us what you think at [email protected]

|

![]()

There Have Been 948 Gun Violence Incidents on K-12 Campuses Since Sandy Hook

|

Dear Meteor readers, Today we reflect on the 10-year anniversary of Sandy Hook, which takes place December 14. What have we learned since then, and where do we go from here? We also have some news. Let’s dive right in. Praying for a different way, Samhita Mukhopadhyay  WHAT'S GOING ONTen years ago: On December 14, 2012, an armed gunman entered Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut and killed 26 people—a majority of whom were children under the age of 10. It was the deadliest mass shooting in an elementary school in U.S. history. Afterward, Americans seemed to agree: Sandy Hook needed to be a turning point. Kids should not be gunned down in their own classrooms. Yet in just a four-year span after Sandy Hook, there was Taft Union High School in California. There was Ronald E. McNair Discovery Learning Academy in Georgia. Sparks Middle School in Nevada. Arapahoe High School in Colorado. Berrendo Middle School in New Mexico. North Thurston High School in Washington. South Macon Elementary in North Carolina. Harrisburg High School in South Dakota. Madison High School in Ohio. Antigo High School in Wisconsin. Mueller Park Junior High School in Utah. All incidents in which teenagers were either wounded or killed. And these incidents aren’t flukes. Over the ten years since Sandy Hook, incidents of school-based gun violence have increased at an alarming rate. According to the Center for Homeland Defense and Security K-12 Shooting Database, 948 gun violence incidents have taken place on K-12 campuses since December 2012. “Gun violence incidents” include any incident where a gun is “brandished, fired, [or] a bullet hits school property for any reason regardless of the number of victims, time of day, or day of week.” As a result, 273 people have been killed, 722 have been wounded, and thousands have been traumatized by witnessing gun violence at school.  For the parents of Sandy Hook, the trauma of their loss was compounded by a new 21st-century ordeal: a mass disinformation campaign that sought to invalidate their experience. Alt-right radio host and conspiracy theorist Alex Jones relentlessly spread lies claiming the shooting was a hoax. He called the parents “actors” and told his audience (who believed him) that Sandy Hook was a staged event intended to remove guns from the hands of law-abiding citizens. Courts ultimately found Jones guilty of defamation and ordered him to pay $965 million in damages to eight of the families. This reckoning wouldn’t have happened without the efforts of Sandy Hook families who, in the wake of this tragedy, refused to be silent about the twin plagues of gun violence and disinformation. As for the direction we’re headed with gun violence: This year saw another series of incomprehensible mass shootings, including the murder of 19 children and two adults at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas. Like Sandy Hook, Uvalde was heralded as a turning point—and many gun reform advocates believe the turning is actually beginning to happen. In June, the Senate was able to reach a deal on gun reform that, while not banning assault rifles outright, did begin to limit who can access them. But as National Youth Poet Laureate Amanda Gorman said, “It takes a monster to kill children. But to watch monsters kill children again and again and do nothing isn’t just insanity—it’s inhumanity.” For the sake of the families of Sandy Hook, let’s not allow this anniversary to be an occasion where we simply mourn the murder of children as an inevitable part of American life. If you take one small action today to protect children from gun violence, consider a donation to Sandy Hook Promise, which works to end violence nationwide through education, gun reform, and (most crucially) a “Know the Signs” program geared toward caring for students who exhibit violent inclinations. Let’s fight for a better future—together.  AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays. Ideas? Feedback? Requests? Tell us what you think at [email protected]

|

![]()

Brittney Griner Is Coming Home

|

Hey! Meteor readers! *bursts through your inbox like the Kool-Aid Man* SO MUCH IS HAPPENING! No time for banter. Let’s dive straight into it. Typing like the wind, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONLong overdue homecoming: After 294 days, Brittney Griner has been released from prison and will soon be reunited with her loving wife, Cherelle. A rundown of how we got here: In February, Griner was detained in Russia after officials found vape cartridges containing cannabis oil in her luggage. Like most WNBA players of her caliber, Griner travels overseas to play for other leagues as a way to make more money during the U.S. off-season. In May, the U.S. government officially acknowledged that Griner had been wrongfully detained—but that move didn’t do her much good. The Russian government kept her in custody and proceeded with a drug trial in July. Griner, who maintained that she had had no intent to break the law, pleaded guilty and was handed the maximum sentence of nine years in a Russian penal colony. Early this morning, President Biden announced that Griner was being safely returned home as a result of a prisoner swap. In exchange for her freedom, the U.S. returned convicted arms dealer Viktor Bout to Russia. Unfortunately, the news is not all good: Griner’s fellow detainee, Paul Whelan, was not included in the swap and remains imprisoned in Russia on suspicion of espionage. Whelan, a former Marine, has been in Russia since 2018. Both he and the U.S. government deny any allegations of espionage. For those of us not directly connected to the Griner family, this ordeal has opened our eyes to so many things that I hope we don’t soon forget—for one thing, that professional women athletes deserve a level of pay that would allow them to do what their male peers do during their sports’ off-seasons: recover.  It’s also Latina Equal Pay Day: a day where I, a working Latina who loves to write about equal pay in sports, and all of my sistren are reminded of the astonishing wage gap that still exists for many of us. This day marks the length of time a Latina would need to work to make as much money as a white guy doing the same job in the previous year. Women on average need to work an additional three months, till March, but Black women until September, Native women until the end of November, and Latina women till today. (But hey the gap for Latinas is closing and we’ll be on par with white men by *counts on fingers* the year 2206.) But as Rebekah Barber and Jasmine Mithani of The 19th point out, Latinas face many other barriers which have contributed to the pay disparity. Latinas are “overrepresented in lower-paid industries such as service and domestic work.” But those of us with undergraduate degrees are “the most underpaid—taking home 31 percent less than White men,” they write. Suffice it to say my student loan lender will get their money when I get mine. (Which, I repeat, could be in 2206.) Are there solutions to close the pay gap? Plenty, like passing the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act and the Paycheck Fairness Act. But any long-term solutions also require systemic change in how we view Latina women’s labor, childcare, and sick leave. Did you know that 51 percent of working Latinas don’t even have access to paid sick leave? And studies about gender-based pay gaps don’t often include undocumented workers or those who exist outside of the gender binary, leaving those populations’ needs largely unknown and unaddressed. I guess you could say there’s a lot of work ahead if we want to feel better about…work.  AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays. Ideas? Feedback? Requests? Tell us what you think at [email protected]

|

![]()

Three Days of Strikes In Iran

|

Evenin’ Meteor readers, Today we’re anxiously awaiting the results of the Georgia Senate run-off election which will decide if Herschel “what even is a pronoun” Walker or incumbent Democratic Senator Raphael Warnock will win the seat. We have reason to be optimistic—but there have already been documented instances of voter suppression and people struggling to get their absentee ballots, changing deadlines and more. In today’s newsletter, we are sifting through the confusion of the recent headlines about the morality police in Iran, applauding some brave Swifties, and checking in on what else is going on in our world. Watching the results come in, Shannon Melero & Samhita Mukhopadhyay  WHAT'S GOING ONSeriously, what is going on in Iran: Over the weekend, The New York Times sent out a breaking news alert announcing that Iran’s “Gasht-e Irshad,” commonly referred to as the “morality police,” had been abolished. The Wall Street Journal and CBS News repeated the headline as well. But that’s not exactly what happened. It didn’t take long for Iranian journalists and those familiar with the situation to chime in with much-needed clarifications. “This is at best a very unclear and inconclusive remark uttered in the middle of a presser,” wrote Arash Aziz on Twitter. Aziz, an author and NYU PhD candidate, explains what he saw in the press conference: Iran’s Attorney General Mohammad Jafar Montazeri made an off-hand comment that was widely reported as fact. As it turns out, Montazeri has no authority to make such a sweeping declaration. Iranian state media eventually confirmed that Gasht-e Irshad has not been abolished, although citizens have reported a diminished presence of the force on the streets. It’s not about a single misleading headline. The reality is that oppressive governments thrive on sowing seeds of confusion—and they have a strong incentive to do so, since their efforts to quiet the protests have failed. And given how fast stories spread on social media (and how much we desire good news), a misinterpreted quote or slightly inaccurate headline can quickly spiral into viral misinformation for Iranian officials to use to obscure what is happening in Iran. In this particular case, Iran’s state media can easily point to an error made by Western media and spin it into a narrative that outsiders are the ones really stoking the fires of revolution and pretend everything in Tehran is peachy. In discussing the response to the Times article, Gissou Nia, an Iranian-American human rights lawyer, told CBC News, “I think it simply underscores that the global community wants a neat resolution to this story and is not realizing that the Iranian people want a full overhaul of the system—not just the morality police.” But here’s what we know to be true: All of this is distracting from the bigger story. The sweeping movement in Iran continues against great odds with strikes, protests, and rallies planned for the majority of this week. The Iranian government is doing its utmost to brutally suppress these actions as well as any reporting on them. And while there may not be a ton of ways to help the women in Iran directly, we can continue to amplify the voices of the activists, agitators, and people on the ground risking their lives to fight theocratic rule and demand equal rights for all citizens. AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays. Ideas? Feedback? Requests? Tell us what you think at [email protected]

|

![]()