Three Questions About...Like, Words and Stuff

Journalist Megan Reynolds takes up the most derided word in the dictionary

By Shannon Melero

Megan Reynolds has always had a way with words, which I experienced firsthand when we worked together at Jezebel, and she told me I could always go to her with any questions. Big mistake, huge! I’ve been pestering her since 2019, and now I have yet another reason: Megan—who has made everything from beach chairs to a really big mall to the terrible sport of baseball come alive with her deft use of language,—has a new book, Like: A History of, Like, the World’s Most Hated (and, Like, Misunderstood) Word. In it, she traces the word’s origins all the way back to the 1600s, and also writes a love letter to the way women, particularly teen girls, have shaped language. As is our routine, I darkened her door with my queries.

So even though women are the ones making fetch happen when it comes to language, this book exists because there’s so much pushback and policing over women’s use of “like.” So I guess my question is, why can’t we just, like, talk how we please?

The answer is absolutely “sexism,” but that is a pat response for a situation that is much more nuanced and complex. Sometimes the call is coming from inside the house—for all the professional men out there who write earnest LinkedIn blogs about filler words, power, and corporate communication, there are just as many professional women doing the same thing. The policing comes in many forms, [including] the voice in your own head, but I’d say that it is most evident in the aforementioned blogs on LinkedIn and op-eds in various newspapers around the world. And, if you watch the season premiere of the most recent season of The Kardashians on Hulu, you’ll find the entire family policing Kourtney for saying like, like, all the time.

On the surface, any policing of women’s language looks like and definitely is sexist, but underneath, is also the issue of intelligence and whether or not saying “like” a bunch when you talk means you’re not. And yes, this is a battle that both men and women face, but women (I assume) are more concerned with not sounding stupid, whereas men will happily open their mouths and share the first thought that comes to mind.

One thing I love is that you described "like" as a word that does a lot of emotional labor, and it's been doing so since before either of us was born. Have you come across a word that is taking on that same labor for the next generation? Or will "like" continue to be a timeless linguistic accessory?

Language moves faster than any of us are interested in thinking about, but I think that “like” will never go out of style—and that’s actually good? It means that it’s become an inherent and natural part of speech, and for that, we are forced to stan. However, the youth of today are saying words in ways that I never could have imagined.

The meaning of “literally” has changed in recent years due to young people using it in unorthodox ways, and I think a lot of people are pressed about that for reasons unbeknownst. Technically, “literally” does mean just one thing, and often, it’s used in situations that are decidedly not literal. And like “like” can function as an intensifier, “literally” does the same thing.

You write about how Serious Feminists™ of the past were also a part of the anti-Like movement. Is there still a sense that we need to sound important if we want to be important?

Like with most things in life, the answer depends on the person. I’ve worked with women who are younger than me but much more “professional,” hewing closer to the traditional and generally accepted definition of what that sounds like. To me, this doesn’t matter at all. And because I’m generally not that “professional” by any commonly-held, old-fashioned standard, my aim in writing this book was to communicate that we don’t need to care about this! It doesn’t matter! If someone is or isn’t going to take you seriously in the workplace or anywhere else, I’d wager that they’ve already made that decision before you even opened your mouth, anyway.

The Loss of a "Deeply Personal Freedom"

June 26, 2025  WHAT'S GOING ONYou don’t get to choose: During our morning meeting, while I regaled my colleagues with Sabrina Carpenter theories, a news alert popped up. I swear a group of women hasn’t gone that quiet that fast since Huda’s last crash-out. The alert was that the Supreme Court had published its decision in Medina v. Planned Parenthood. The court ruled 6-3, along ideological lines, that South Carolina’s governor, Henry McMaster, was on sound legal footing when he removed Planned Parenthood South Atlantic from the state’s Medicaid program in 2018. To be clear, South Carolina already outlaws abortions after six weeks, and the Hyde Amendment has long ensured that federal funds cannot be used to reimburse abortion costs anyway. (State funds are a different story.) This case is about punishing Planned Parenthood for its association with abortions, even though its clinics also provide STI screenings, contraception, mammograms, and a number of other vital health services. A 2021 study found that of the millions of women Medicaid recipients who had gone to Planned Parenthood for care that year, 85 percent of them received contraceptive services. That means that when McMaster removed PPSA from the Medicaid program, any Medicaid patient going to one of its clinics lost their healthcare provider, which is why PPSA and one of its patients sued McMaster for violating the “free choice of provider” clause in the Medicaid Act. The lower courts sided with the plaintiffs repeatedly. But the state’s director for the Department of Health and Human Services picked up the fight, and SCOTUS decided that losing access to your health provider is not a violation of your rights. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, who wrote the dissenting opinion, characterized this decision as “stymying one of the country’s great civil rights laws” and Slate points out, associated the majority with white supremacists who once sought to undermine Reconstruction. She deftly laid out what this decision will really do: “It will strip countless other Medicaid recipients around the country of a deeply personal freedom: the ‘ability to decide who treats us at our most vulnerable.’ ”  THE FACE OF A WOMAN WHO IS TIRED OF THE TOMFOOLERY IN THE COURT. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) For patients outside South Carolina, this decision could have a ripple effect. Governors nationwide now have the runway they need to essentially defund Planned Parenthood in their states by blocking the organization’s access to Medicaid funds, which account for one-third of Planned Parenthood’s revenue. At the same time, Republicans are trying to eradicate the organization via the Big Beautiful Bill, which seeks to end Medicaid reimbursements to Planned Parenthood nationally. If passed, the bill “could lead nearly 200 clinics to shutter—90% of them in states where abortion is legal,” independent journalist and Autonomy News cofounder Susan Rinkunas told The Meteor. “If the Trump administration is able to nationalize this Supreme Court decision, people even in protective states would have less access to reproductive healthcare, including abortion.” Bottom line: This decision goes beyond attacking bodily autonomy. Today, the court reaffirmed that being poor, or a woman, or Latine, or Black—the groups that make up the majority of Medicaid users—means that the freedoms and choices enjoyed by everyone else don’t apply to you. If you don’t have the money or the whiteness or the penis to pay for the doctor you want, you’re out of luck. AND:

HOW'S THAT FOR A WARM VENETIAN WELCOME? (GETTY IMAGES)

Three Questions About...Toni MorrisonShe had a whole other job, and she was brilliant at it. BY REBECCA CARROLL  COURTESY OF HARPER COLLINS Toni Morrison wrote some of the greatest literature of all time. It is less known, though, that she also edited some of the greatest literature, and that is what makes Dana A. Williams’s new book, Toni At Random: The Iconic Writer’s Legendary Editorship, such a gift. Williams, a professor of African American literature and the Dean of Graduate School at Howard University, conducted hundreds of interviews (including a handful with Morrison while she was still living) and unearthed letters and conversations between Morrison and the authors she published—among them Toni Cade Bambara, Lucille Clifton, Gayl Jones, and Angela Davis—during her nearly 20 years as an editor at Random House. The result is a thoughtfully reverent, always engrossing, and occasionally juicy narrative that confirms Morrison’s intricate genius, as well as her deep love of Black writers, Black books, and Black language. Rebecca Carroll: What did you learn about Toni Morrison, the editor, that you did not know about Toni Morrison, the writer? Dana A. Williams: I think they intersect, but Toni Morrison as editor was fully involved in the publishing community. I think of Toni Morrison-as-writer as someone writing in isolation—someone writing at their desk, really thinking about her story and her characters. Morrison as editor was everywhere. She was at every party. She was in the design team’s face, sometimes to their dismay. She was on the street trying to find writers, because she really did have to kind of beat the bushes in those early years to identify writers who had not been signed up by other houses. Angela Davis told me that her office was always bustling. There were people in and out all the time, which is part of the reason why, when she was working on a book of her own, she would not go in the office in the same way. One of the beautiful things about this book has been rediscovering books I’ve loved forever, like Toni Cade Bambara’s Gorilla, My Love, now knowing that Morrison played such an integral role in shaping them. Were there books that you returned to in the same way during the process of writing this one? I absolutely went back and reread [Bambara’s] The Salt Eaters because I thought, Now I think I know what’s happening in this book. I love The Salt Eaters. I taught The Salt Eaters, but I never got all of it. The same thing was true of Leon Forrest, who I probably knew more about than any of the authors. All the fiction—the fiction [Morrison edited] was what I was so drawn to to begin with….But the more [Morrison and I] talked, the more she continued to ignore my questions about fiction. She was like the queen of indirection from the beginning to the end, because she never said, “This book really shouldn’t be about the fiction only.” She would drop hints like, “Have you seen Paula’s last book? Now that’s a book. If you’re going to write a book, that’s a book.” She was talking about A Sword Among Lions by Paula Giddings, which was interesting, because it is a biography of Ida B. Wells, and every time I would ask [Morrison] a question about herself, she would say, “I'm not interested in myself.” After spending over a decade on this book, do you have a strong sense now of what Toni Morrison thought made good writing? I kept asking her that question, and she said, “Well, obviously if it’s nonfiction, the argument has to be sound and it has to be compelling, and it has to make the case for the reader in a way that nobody else has made it before.” If she was editing on a topic that she didn’t know as much about, she was literally reading everything about the current conversation to make sure [the author was] moving this argument in a different direction. Editors don't have to do that. For the fiction…I think she was more drawn to experimental writers than to straight beginning, middle, and end writers. She said, “With Gayl Jones, I had to ask questions about characters: What is motivating this character?” With Bambara, she said, “I just needed to make sure that she didn't leave the reader behind, because she’s moving so fast.” I kept thinking, There has to be this kind of crystallized way of saying [what good writing is]. But it was the interrogation. I think that was her distinguishing mark—to publish what stories she wanted to be told, and to let the writer be the writer.  WEEKEND READING 📚On something different: Babe, wake up, a new kind of masculinity just dropped, and it involves Pedro Pascal. (TCF Emails) On the worst trimester: Vox’s podcast, “Unexplainable,” tells the story of geneticist Marlena Fejzo, whose own torturous pregnancy led her to discover both a biological cause and potential cure for morning sickness. (Vox) On evolving the stitch and bitch: Knitting clubs were once a place to complain about your kids and mother-in law (not me I would never), but young knitters are using their craft for a greater good. (Teen Vogue) On what we eat: Food affects everything, but can it really do much about menopause, or are women being sold another fad diet? (Burnt Toast)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Three Questions About...Toni Morrison

She had a whole other job, and she was brilliant at it.

By Rebecca Carroll

Toni Morrison wrote some of the greatest literature of all time. It is less known, though, that she also edited some of the greatest literature, and that is what makes Dana A. Williams’s new book, Toni At Random: The Iconic Writer’s Legendary Editorship, such a gift. Williams, a professor of African American literature and the Dean of Graduate School at Howard University, conducted hundreds of interviews (including a handful with Morrison while she was still living) and unearthed letters and conversations between Morrison and the authors she published—among them Toni Cade Bambara, Lucille Clifton, Gayl Jones, and Angela Davis—during her nearly 20 years as an editor at Random House. The result is a thoughtfully reverent, always engrossing, and occasionally juicy narrative that confirms Morrison’s intricate genius, as well as her deep love of Black writers, Black books, and Black language.

Rebecca Carroll: What did you learn about Toni Morrison, the editor, that you did not know about Toni Morrison, the writer?

Dana A. Williams: I think they intersect, but Toni Morrison as editor was fully involved in the publishing community. I think of Toni Morrison-as-writer as someone writing in isolation—someone writing at their desk, really thinking about her story and her characters. Morrison as editor was everywhere. She was at every party. She was in the design team’s face, sometimes to their dismay. She was on the street trying to find writers, because she really did have to kind of beat the bushes in those early years to identify writers who had not been signed up by other houses. Angela Davis told me that her office was always bustling. There were people in and out all the time, which is part of the reason why, when she was working on a book of her own, she would not go in the office in the same way.

One of the beautiful things about this book has been rediscovering books I’ve loved forever, like Toni Cade Bambara’s Gorilla, My Love, now knowing that Morrison played such an integral role in shaping them. Were there books that you returned to in the same way during the process of writing this one?

I absolutely went back and reread [Bambara’s] The Salt Eaters because I thought, Now I think I know what’s happening in this book. I love The Salt Eaters. I taught The Salt Eaters, but I never got all of it. The same thing was true of Leon Forrest, who I probably knew more about than any of the authors. All the fiction—the fiction [Morrison edited] was what I was so drawn to to begin with….But the more [Morrison and I] talked, the more she continued to ignore my questions about fiction. She was like the queen of indirection from the beginning to the end, because she never said, “This book really shouldn’t be about the fiction only.” She would drop hints like, “Have you seen Paula’s last book? Now that’s a book. If you’re going to write a book, that’s a book.” She was talking about A Sword Among Lions by Paula Giddings, which was interesting, because it is a biography of Ida B. Wells, and every time I would ask [Morrison] a question about herself, she would say, “I'm not interested in myself.”

After spending over a decade on this book, do you have a strong sense now of what Toni Morrison thought made good writing?

I kept asking her that question, and she said, “Well, obviously if it’s nonfiction, the argument has to be sound and it has to be compelling, and it has to make the case for the reader in a way that nobody else has made it before.” If she was editing on a topic that she didn’t know as much about, she was literally reading everything about the current conversation to make sure [the author was] moving this argument in a different direction. Editors don't have to do that.

For the fiction…I think she was more drawn to experimental writers than to straight beginning, middle, and end writers. She said, “With Gayl Jones, I had to ask questions about characters: What is motivating this character?” With Bambara, she said, “I just needed to make sure that she didn't leave the reader behind, because she’s moving so fast.” I kept thinking, There has to be this kind of crystallized way of saying [what good writing is]. But it was the interrogation. I think that was her distinguishing mark—to publish what stories she wanted to be told, and to let the writer be the writer.

Moving Past the Shock of Dobbs

June 24, 2025 Salutations, Meteor readers, Today is the third anniversary of the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, which overturned nearly 50 years of federal protection for abortion rights. I wish I could say I never thought we’d see the day, but as a member of the post-Y2K, post-9/11, post-’08 recession, post-COVID, post-Roe generation, there isn’t a crisis I haven’t lived through. Honestly, just waiting for the rivers to turn to blood…oh wait. In today’s newsletter, we look at our disturbing new normal and try to move past our post-Dobbs shock. At least we have each other, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONTime has truly flown since 2022, when so many of us spent the day wondering, what do we do now? In the time since we’ve marched, donated, voted for abortion, made podcasts, and learned just how far people in power are willing to go to limit our bodily autonomy. So, how does the reality of a post-Roe America differ from what we once predicted? Let’s take a look:

Grey’s Anatomy can’t hold a candle to the high-stakes medical drama of the last three years. But, as in any good series, there have been some small wins. While abortion rights of patients in red states have been gravely curtailed, protections have actually gotten stronger in many blue states, thanks to laws codifying the right to abortion in state constitutions. And across the country, clear majorities have voted to protect reproductive rights, even in red states like Kansas and Kentucky. This political backlash has pleasantly surprised experts like Jennifer Klein, a professor at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs and the former director of the White House Gender Policy Council, who joined us on IG Live today, and said she was heartened to see that “abortion absolutely matters to voters.” “The level of resilience and ability to organize and fight back” has been surprising, she added, but it also “gives me hope.” AND:

COMPOSITE IMAGE OF THE TRIFID AND LAGOON NEBULAE FORMING A SICK PINK CLOUD NEAR THE CONSTELLATION SAGITTARIUS. (SCREENSHOT VIA YOUTUBE)  What Comes After Shock?Maybe something better—something steelierBY CINDI LEIVE  PROTESTORS ON LAST YEAR'S DOBBS ANNIVERSARY. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) You’ve read from my colleagues Nona and Shannon, above, about the realities of life three years after Dobbs. So one more question: How are we feeling? Three years ago today, with the devastatingly blunt sentence “Roe and Casey are overruled,” Justice Samuel Alito shattered any illusion that women in this country are, at least on paper, seen as full human beings. Reading those words wasn’t surprising—a draft of the decision had been leaked seven weeks earlier and, y’know, there were far earlier signs—but it was shocking, the way losing a loved one comes as a shock no matter how sick you knew they’d been. The shocks came rapid-fire after that: When my colleagues and I spoke to a woman who was being driven into debt after being forced to continue a debilitating pregnancy—shocking. When Kaitlyn Joshua told her story of being ping-ponged, bleeding, from one Louisiana hospital to another, none willing to treat her—shocking. When a young mom in Alabama confided that she’d been passed a stickie note telling her to travel 580 miles for care—shocking. When Jessica Valenti reported that South Carolina had proposed the death penalty for abortion patients—shocking! But, as grotesque as it is to admit, I am no longer shocked, and you might not be either. The harrowing recent case of Adriana Smith, the Georgia woman declared brain-dead but kept alive by medical staff because she was pregnant, is the stuff of horror movies, and the kind of case that at a different time and under a different president would have dominated headlines for weeks. But it seemed to me it received only modest coverage—partly because we are now living in a multiplex of horror movies (from ICE to anti-LGBTQ attacks), and partly because, after 36 long months, the shock has just worn off. This is where we are. So what happens next? On one level, of course, we have to try to retain our capacity to be shocked—to remind each other that using humans as incubators (or seizing people from their workplaces) is the kind of cruelty that may be the norm but will never be normal. I’m grateful to journalists and advocates (from Valenti to the reporters at ProPublica to legislators like Rep. Jasmine Crockett) who use their voices, data and rage to startle us day after day. But maybe there’s something more effective than shock. After all, medically speaking, when you’re “in shock,” you’re confused, weakened, not playing with a full cognitive deck—and that is the last place we want to be right now. The people I admire in this fight are using their steely resolve, legal brilliance, vast compassion, medical genius and joy every day. They have long abandoned shock, well aware that the rollback of bodily autonomy in this country is part of a well-documented global autocratic playbook in countries like Hungary, Turkey, and Venezuela. They don’t need us to be stunned. They need us to be alert, and committed, and creative—and together. What are you feeling on this anniversary? Write us at hello@wearethemeteor and let us know.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

It's Been Juneteenth All Year Long

June 18, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, Tomorrow is Juneteenth, so our offices (and maybe yours) are closed. But we couldn’t shut down our laptops without leaving you with a little bit of relevant reading and listening. Today Rebecca Carroll walks us through a year that, in spite of it all, has been culturally Black as fuck. Afterward, if you feel like luxuriating a little longer, read six incredible women on what they believe is the true meaning of Juneteenth. And of course, it wouldn’t be a celebration without hearing from Opal Lee, the “grandmother of Juneteenth,” who spoke with Brittany Packnett Cunningham a few years back about her relentless work to make this holiday a reality. Our thoughts are with Ms. Opal this week as news recently broke that she will not be leading the annual Walk for Freedom in Fort Worth, Texas, due to health complications. Remembering it’s a we thing, Shannon Melero  The Black Cultural Abundance of JuneteenthThis year, for me, Juneteenth started on February 9.BY REBECCA CARROLL  STILL THINKING ABOUT HIM (VIA GETTY IMAGES) I’ve watched it four times. Every time it’s given me something different. But what it has given me overall—in its multi-layered, legacy-laden, undeniably art-centric symbolism—is the assurance that one thing Black folks are always gonna do is find our freedom reflected in each other. I’m talking about Kendrick Lamar’s halftime show at Super Bowl LIX. It became the most-watched halftime show in history, drawing in more than 133 million viewers, and it felt not only like a call to action—because “sometimes you gotta pop out and show”—but also the very best of what Juneteenth invokes for me. Black folks’ relationship with America is obviously fraught. The country was built on our backs. Slavery is as foundationally American as the Super Bowl. And Juneteenth is, ostensibly, about American freedom. But even after the Emancipation Proclamation, Black Americans were still widely not considered to be free civilians, and that is why we continue to seek that freedom out in and for each other. After tennis star Coco Gauff won the 2025 French Open earlier this month, she said, “Some people might feel some type of way about being patriotic, but I’m definitely patriotic and proud to be American. I’m proud to represent the Americans that look like me.” And that was also the beauty of Lamar’s show—he could have easily declined to perform at such a mainstream Americana spectacle. Instead, he used it as an opportunity to reconfigure the American flag through the formation of his all-Black backup dancers, who wore red, white, and blue. Recently, when a young Black woman asked me how I write for my specific audience of readers, I said, “The same way Kendrick Lamar just performed the Blackest-blackety-black halftime show performance at the Super Bowl, for his specific audience of viewers, Black folks.” Because we know how to find each other, and speak to the insides of one another. It’s in the tradition of call-and-response, of ancestral homage, dignity, and legacy. It’s in our DNA. And it is an aegis of Black cultural jubilation in a year of targeted demoralization—when Black historic landmarks, Black museums, Black books and course curricula, and DEI initiatives are being defunded, denigrated, and dismantled.  GAUFF WITH THE ROLAND GARROS TROPHY WHICH SHE LATER AND HILARIOUSLY REVEALED IS NOT THE TROPHY CHAMPIONS GET TO TAKE HOME. (VIA GETTY) In the months after Lamar made the call, those responses have kept coming. Next came Ryan Coogler’s supernatural horror movie, “Sinners,” which both killed at the box office and earned glorious reviews. Like the Super Bowl show, “Sinners”—which follows twin bootlegging brothers who return to their Mississippi hometown to open a juke joint—is kaleidoscopic and heady, containing layers upon layers of historical references and truths. Amid recent indignities, Coogler managed to give us something rapturous, restorative, and unwavering in its tribute to Black freedom, Black love, and Black ingenuity. And then came Beyoncé’s “Cowboy Carter and the Rodeo Chitlin’ Circuit Tour,” an all-stadium concert tour celebrating her Cowboy Carter album, which explores the Black roots of country music (another quintessentially American institution). Yes, Beyoncé is an extraordinarily talented and iconic artist. But what has stood out the most to me about the Cowboy Carter tour is not Beyoncé herself but the way her daughter Blue Ivy, with every bit of her badass, 13-year-old self, has showed out to perform with her mother onstage, giving a kind of “fuck-you”-fueled intensity well beyond her years. To me, Blue Ivy represents the collective power and tenacity of Blackness, and I imagine is exactly what the ancestors had in mind when they thought, We gonna call it Juneteenth, and then we gonna do whatever the hell we want to on this day forward from heretofore.  CAN WE GET A YEE-HAW? (VIA GETTY IMAGES) And then there was The Met Gala. While I have real criticisms about the event as the standard of what constitutes haute fashion, and about its curated exclusivity (read: whiteness), I couldn’t help but feel like this year’s theme, “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style,” was another response to Lamar’s call. Inspired in part by Black scholar Monica L. Miller’s book, Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Style of Black Diasporic Identity, all our fave fancy Black folks walked that blue carpet wearing the fiercest looks, channeling the very essence of Black elegance, just like the one that Black folks have historically created for Juneteenth celebrations.  SO...ABOUT THAT ALBUM? (VIA GETTY IMAGES) After that, the ancestors came through…again: It was as if Annie, the Hoodoo healer from “Sinners,” gathered together a very particular recipe of roots and herbs to help conjure up some very large flames on a very specific plot of Southern land. It’s not nice to say, but when the largest surviving plantation mansion in the South burned to the ground on May 15, my first thought was, “Well, you shouldn’t have been enslaving people.” The demise of Nottoway Plantation in White Castle, Louisiana—which, like many plantations, had become a popular wedding venue—was reportedly caused by an electrical fire. Whatever the case, for it to happen during this run of Black cultural ascension seemed like poetic justice, and needless to say, the Black memes were delicious. There are many more examples—Amy Sherald, Lorna Simpson, Rashid Johnson, and Jack Whitton all having solo art shows this year; Audra McDonald being a classy boss bitch, and giving an utterly singular “Gypsy” performance at the Tonys; Rihanna continuing to populate so glamorously—but given where we are in this moment, it feels right to end with Doechii’s speech at the BET Awards last week. Because ultimately, Black freedom has always meant getting other people free, too. Doechii, who won the award for Best Female Hip-Hop Artist, chose to use her platform during the live broadcast to speak out against the ICE immigration raids happening in Los Angeles. “These are ruthless attacks that are creating fear and chaos in our communities in the name of law and order,” she said. “I feel it’s my responsibility as an artist to use this moment to speak up for all oppressed people: for Black people, for Latino people, for trans people, for the people in Gaza.” Juneteenth, which became a federal holiday in 2021, is about Black freedom. But it’s also about the function of freedom itself.

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

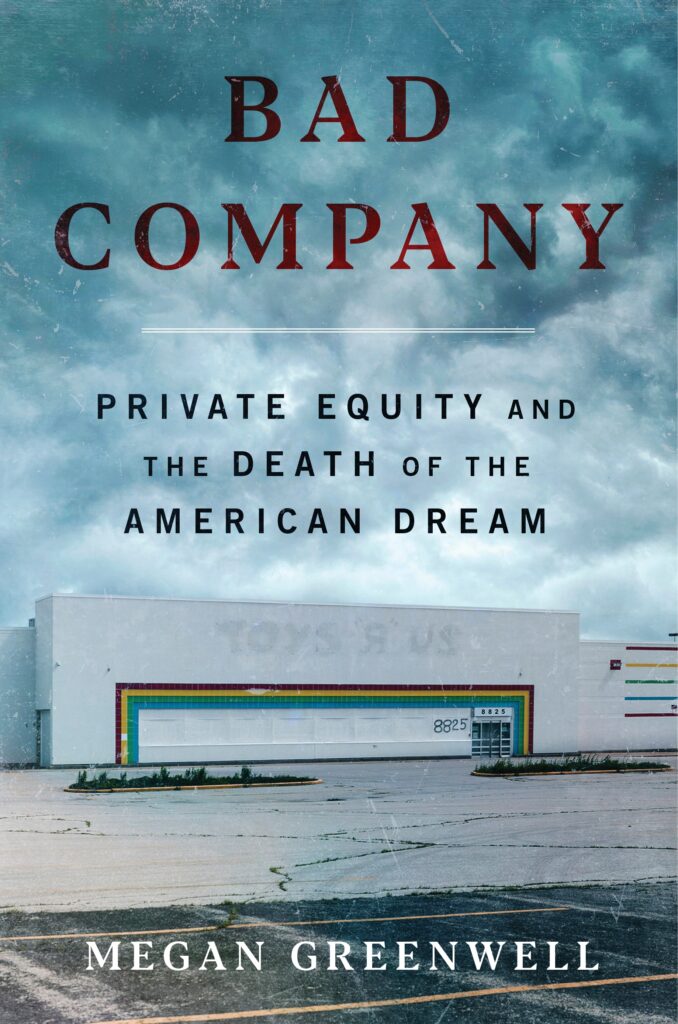

Three Questions About...Private Equity

In her new book, author Megan Greenwell humanizes the horrors of a secretive industry

By Nona Willis Aronowitz

When journalist Megan Greenwell scored her dream job as the editor-in-chief of the sports website Deadspin, she hadn’t thought about private equity at all. She had never done any finance reporting, and she had only the vaguest sense of what private equity even did. But when, in 2019, Deadspin was being destroyed by the firm that owned it, she wrote a scorched-earth resignation letter and resolved to learn more about the human cost of this ubiquitous and insidious industry. Her resulting book, Bad Company: Private Equity and the Death of the American Dream, tells the story of four people whose lives were upended by private equity–and how they all fought back.

John Oliver once said, “If you want to do something evil, put it inside something boring.” Your book is not boring, but I think for many of us, our eyes glaze over at financial terms we don’t know. How do you explain private equity to get laypeople to care?

The only way I wanted to write this book was if it was for people who have some sense that private equity is important and has negative consequences, but have zero idea what that means. Here’s how I describe it: The engine of the private equity machine is leveraged buyouts, which are when a private equity firm pools money from outside investors–pension funds, university endowments, ultra-wealthy individuals, what have you–and combines that money with a huge amount of bank loans, then uses that combined fund to buy companies.

The trick is that the debt from the loans is assigned not to the private equity firm but to the company it is acquiring. That’s the detail I think gets people scandalized. They take companies that are pretty strong in a lot of cases and turn them into companies absolutely hamstrung by debt payments, and as a result, 10 times as many companies owned by private equity declare bankruptcy than other kinds of companies. The private equity firms themselves don’t take on any risk, but this has horrible effects on communities, workers, tenants, patients, everybody.

The book’s subtitle mentions “the death of the American dream.” How did this theme play out in your reporting? (Also, I have to ask: Was it just a coincidence that three out of four of your protagonists were women, or do you think there’s a throughline there?)

I picked the industries first, and I landed on media, healthcare, retail, and housing. Private equity didn’t cause the root problems in these industries; instead, they capitalized on those problems for their own gain. Once I had my protagonists, the interviews drove the American Dream theme rather than the other way around. One is a Mexican immigrant who moved here in middle school, not speaking a word of English, and who managed to become a professional journalist. Another grew up poor in Texas, and his version of the American dream was becoming a community doctor who provided care to his neighbors. Another was a woman who escaped public housing (and a lot of other things), so for her, living in her apartment complex really was the Dream. And the last woman is an Alaska native who moved to the mainland and supported a family of five on a Toys “R” Us retail salary so her husband could go to pharmacy school and make a better life for all of them. In each case, private equity ended up tearing down the things that were most important to these people.

[And about the three-out-of-four women factor,] it’s not surprising to me that women were the majority of people I ended up talking to–not just [of] the four, but the 150 to 200 people I spoke with before I found my protagonists. In part, it’s because there are specific vulnerabilities of being a woman in 21st century America [like poverty] but also because I chose people who were fighting back, and women seem to be more involved in these community fights.

Yes–all of your subjects actively resist their circumstances to varying degrees after private equity shatters their lives. What can someone whose job or industry is being eviscerated by private equity learn from the people in your book?

The four characters in my book all fight back in very different ways. Some put pressure on elected representatives [to regulate private equity]–although there are limitations to that at the federal level, because fully 88% of members of Congress and the Senate take private equity donations. Another character does some lobbying in front of pension funds to get them to stop investing in private equity firms that hurt workers. There’s some true grassroots community organizing to build something new. Some of the most interesting reporting I did was in the media section, where the focus is on people who are trying to create a new nonprofit system. Is that at a big enough scale now that it is fully replacing private equity-owned corporate media? No. But some startup nonprofit local news sites are doing really, really well economically and are becoming amazing sources of news in places that didn’t have news. I think about Mississippi Today, which did not exist until a few years ago, but which won a Pulitzer by exposing a massive scandal in the governor’s office involving Brett Favre. That’s genuinely inspiring to me.

"Trying to Break Us Won't Work"

June 10, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, It was a long weekend, especially for these two. Let’s jump right in. In today’s newsletter, The Meteor’s Angie Jaime writes to us from the West Coast to share what the last few days (and months) have been like in Los Angeles. Plus, the return of our better-news series, Tell Me Somethin’ Good. xoxo, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONDispatch from Los Angeles: To hear national news tell it, the protests resisting immigration raids in L.A. are the product of ICE’s recent violent overreach, but the truth for those of us who live here is much more complex: The block has been hot, so to speak, for months. ICE has been roving the streets of Los Angeles actively since at least February, just weeks after historic wildfires had devastated the city, effectively kicking the community while we were already down. In my own Highland Park on the eastern side of town, ICE began appearing in my neighborhood about six weeks after the fires that forced us to evacuate; the agents began installing street blockades near schools and doing random door-to-door investigations, setting the community on edge. Then, last weekend, ICE activity roiled to a boil, when agents conducted raids at multiple Los Angeles-area locations Friday, arresting upwards of 200 people per day, sparking protests that drew thousands to the streets. But it isn’t the protests that are sending my city into disarray. My neighbors and I are distressed because of the terrorizing actions of ICE and local police, made worse by Trump’s decision to send in the National Guard and now the Marines over our own state’s objections. A cynical—and, let’s be real, accurate—assessment would be that this is occurring by design, that the military presence is an attempt by the Trump administration to break a wounded city into factions that would turn on its most vulnerable. But that’s clearly a strategy of someone with a grudge against California, who does not know or understand Los Angeles in all her complexity, massive and minuscule.  WHO DOESN'T LOVE A GOOD(VIA GETTY IMAGES) Trying to break us won’t work. In the face of both ICE and its unasked-for armed backup, community members have risen up to resist on behalf of those targeted. Protesters of all intersecting identities, young and old, of all genders and races, from across the county, have put their bodies on the line for their fellow citizens, for their families, for people they may never meet., Many community organizers who had previously mobilized around wildfire recovery, Palestinian free speech in the entertainment industry, and other urgent causes have quickly pivoted to protests against ICE—showing that in a time of need, Angelenos have one another’s backs. And by the way, L.A. is not a war zone. In Highland Park this weekend, the cookouts continued apace, the park where I took my six-month-old was teeming with laughing children, and the neighborhood shops were as filled as they are on any other Sunday. The fear, the horror, the agitation do not come from whatever actions protesters might take in expressing themselves. The fear looms because my neighbors may be snatched from their homes at any moment, because the government continues to escalate force against its own people in the pursuit of white supremacy, because regardless of status, being Brown means that nothing precludes you from having your family torn apart by ICE. And yet, Los Angeles is my home and will remain so, in no small part because of the people who make up its foundations. As a philosopher-poet once said, “It wouldn't be L.A. without Mexicans/It’s Black love, Brown pride in the sets again.” —Angie Jaime So how can you help? Volunteering with legal aid services, sharing resources, and financially supporting local aid funds all work (and, of course, urge your members of Congress to raise their voices—this is not normal). AND:

TELL ME SOMETHIN' GOOD 🎶

RM (L) AND V (R) WERE DISCHARGED FROM SERVICE THIS WEEK AND WERE MET BY A CROWD OF FANS IN CHUNCHEON, SOUTH KOREA. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Trump's Updated EMTALA Guidance Tells Docs, "You're On Your Own"

BY SHANNON MELERO AND NONA WILLIS ARONOWITZ

On Tuesday, the Trump administration rescinded guidance the Biden administration had issued in 2022 explicitly stating that hospitals are to provide abortion care to patients in emergency medical situations, even if the hospital is located in a state with an abortion ban. The guidance came just as news of desperately ill pregnant women being turned away from hospitals was beginning to emerge, and it clarified the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), a 1986 law that requires hospitals receiving federal funding to provide stabilizing care for any individual experiencing a medical emergency. This week, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services said in a statement that the 2022 guidance did “not reflect the policy of this administration” and that it would “work to rectify any perceived legal confusion and instability created by the former administration’s actions.”

Which is ironic, because the thing currently creating massive confusion among providers, patients, and the media is the rescission of the guidance, not the guidance itself. Allow us to clarify: EMTALA has not been repealed; it is still the law of the land and, should you need care in an emergency, your nearest hospital is obligated to provide it or to transfer you to a facility that can—yes, even if that care includes an abortion.

“I want patients to know that nobody should be denying you care because of this memo,” Dr. Dara Kass, a former regional director at the Department of Health and Human Services and an emergency physician in New York, tells The Meteor. And if you do think your providers violated EMTALA, she notes, you can still issue a complaint.

So what’s the purpose of the memo, if it doesn’t change the law? Trump may just be looking for a way to pay lip service to the anti-abortion movement. And the memo’s specific language may also be strategic, as Jessica Valenti points out in her newsletter: The CMS memo says EMTALA still requires treatment of “emergency medical conditions that place the health of a pregnant woman or her unborn child in serious jeopardy.” The phrase “unborn child” (which also appears in EMTALA) hints at fetal personhood and sets up a showdown between a woman who has a life-threatening condition, like an ectopic pregnancy, and her fetus.

It’s all very chaotic. And chaos is the point.

“This action doesn’t change hospitals' legal obligations,” Fatima Goss Graves, president of the National Women’s Law Center, said in a statement, “but it does add to the fear, confusion, and dangerous delays patients and providers have faced since the fall of Roe v. Wade.” Dr. Kass adds that while the 2022 guidance “signaled to doctors that the government had their back,” the rescission tells doctors, “You’re on your own” and erodes their confidence that the government will protect them. There will inevitably be more “physicians who are not sure what they’re allowed to do,” she says, “and therefore they might do less.”

Meanwhile, more pregnant patients will suffer as doctors are forced to contend with legal quandaries under pressure. We’ve already seen what happens when emergency rooms are slow to act; Amanda Zurowski, Kaitlyn Joshua, and Amber Nicole Thurman have each paid the price for a hospital’s confusion over what doctors are allowed to do—Thurman with her life.

For better or worse, Dr. Kass doesn’t see this latest move as dramatically changing “the care on the ground.” (Indeed, even with the 2022 guidance in place, there have been dozens of documented cases of pregnant women being denied emergency care or treated negligently.) Rather, she sees this as “a distraction from what we need to do—which is to reinstate access to abortion services in every state.”

A Plea for the "Disappeared" at the Statue of Liberty

June 3, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, I want to extend the happiest of Happy Prides to all the organizers and participants of a historic sporting event that took place in Oslo on Sunday, the Ruck You Match. The event was a rugby game with a team of cis gender women scrapping against a team of trans women. It was organized as a big ruck you to a spate of bans on transgender women in sports. (If you’re curious, the final score was 34-7 with the cis women’s team coming out on top.) In today’s newsletter, we talk to filmmaker and activist Paola Mendoza about uplifting the stories of disappeared Venezuelans. Plus, a little good news for the girls and the gays, and a rundown of big upcoming Supreme Court decisions. 🏳️🌈♥️, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONYearning to breathe free: Last Sunday, a group of strangers dressed in white sat, screamed, and held hands at the base of the Statue of Liberty. Before them stood filmmaker and activist Paola Mendoza, reading the names of the 238 Venezuelan men who have been “disappeared” by the Trump administration and sent to the El Salvadoran mega-prison Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo (CECOT). The demonstration, spearheaded by Mendoza, was a re-enactment of the now-infamous images of detained Venezuelan men being brought into CECOT, where they’ve been cut off from their families, along with any shred of due process.  (PHOTO BY KISHA BARI) When Mendoza conceived of the protest, she chose to center the men’s humanity—to remind everyone of the 238 human beings getting treated like political pawns. “I'm desperately trying to refuse to allow [these disappearances] to become normalized, to allow it to just be the banality of regular life,” she said. “How I do that is by uplifting stories, to say, ‘This is not normal … and we cannot allow it to become normal.’” One of the names Mendoza read was that of Ysqueibel Peñaloza, who was sent to CECOT in March despite having no criminal record in any country. Peñaloza was in the U.S. legally on a CBP One application, and was with friends shooting a music video when ICE agents raided the home and arrested him and several others. His mother, Ydalis Chirinos, has been vocal about her son’s plight. “Ysqueibel is one of the two greatest treasures that God gave me,” Chirinos tells The Meteor, and yet “I have no knowledge of how my son is being treated.” Chirinos, who is 50 years old and lives in Venezuela, says she waits up nearly all night hoping to hear from her son or his lawyers; the loss of sleep makes it hard to care for her daughter and ailing father. As she waits for the legal system to run its course, Chirinos appeals to the mercy of those in the United States: “What is happening has no explanation, at least for me, since we are human beings and children of God. We do not leave our country for pleasure, we do it out of necessity…I sincerely ask you to help me.”  THE FIRST GROUP OF MEN SENT TO CECOT IN MARCH. THEIR HEADS WERE SHAVEN UPON ARRIVAL AND THEIR HANDS AND FEET ARE CHAINED TOGETHER. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Mendoza is hopeful that more Americans will hear pleas like Chirinos’. “[Prison abolitionist] Mariame Kaba says that hope is a discipline,” she said. “And this is when we have to be the most disciplined.” She posits that even though all sides generally agree that the immigration system is broken, the entire debate can be boiled down to a “yes” or “no” question: “Do you want to be a place that welcomes immigrants, or do you want to be a place that disappears them?” Increasingly, the U.S. looks like the latter; an anti-immigrant domino effect has been rolling out since the Obama administration, and with recent decisions from the Supreme Court, the Trump administration is poised to do even more damage. Nonetheless, “if we can figure out a way to get ourselves to the moon, figure out a way to create cell phones and process data and create AI centers,” Mendoza said, “then you got to fucking believe that we also could figure out a way to fix this immigration system. But there isn’t a [political] will or desire to do so and that is the problem, not immigrants.” Which is why the work of changing public opinion is so essential. Mendoza recounts the advice given to her by Morena Herrera, a former guerilla and reproductive rights activist in El Salvador: “She told me all regimes fall. How long a regime lasts is up to the people. AND:

SOME OF THE MADLEEN'S CREW MEMBERS ON THE DAY THEIR VOYAGE BEGAN. (VIA GETTY AIMGES)

CHEAT SHEET

What SCOTUS Is About to Do to Our Summer

BY CINDI LEIVE  PROTESTERS GATHERED OUTSIDE OF THE COURT EARLIER LAST MONTH TO SPEAK OUT AGAINST THE ADMINISTRATION'S THREATS TO BIRTHRIGHT CITIZENSHIP. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Welcome to June, the month when the most legally-obsessed person in your friend group (hi, that’s us) starts compulsively refreshing the Supreme Court opinion site to be first to know what the Robed Ones have planned for our futures. These are the hot summer weeks that, in past years, have made us rejoice, rage, and panic—and 2025 will be a doozy: The justices are expected to rule on a raft of major cases with real-life, national impact before they break for the summer. A taste of what’s ahead:

Exhausted? Same. And that doesn’t even include big cases on pornography, Obamacare, or everything that joins the birthright case on the “emergency docket”—which is bulging lately given the steady stream of challenges to legally nonsensical White House orders. Stay tuned for more as the decisions roll out. And give thanks for the three queens of SCOTUS sanity, Sonia Sotomayor, Ketanji Brown Jackson, and Elena Kagan, who continue to stand for the law and our rights through all of it.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Is the Last Abortion Haven in the Caribbean Closing?

How U.S. influence has been quietly reshaping access in Puerto Rico

By Susanne Ramirez de Arellano

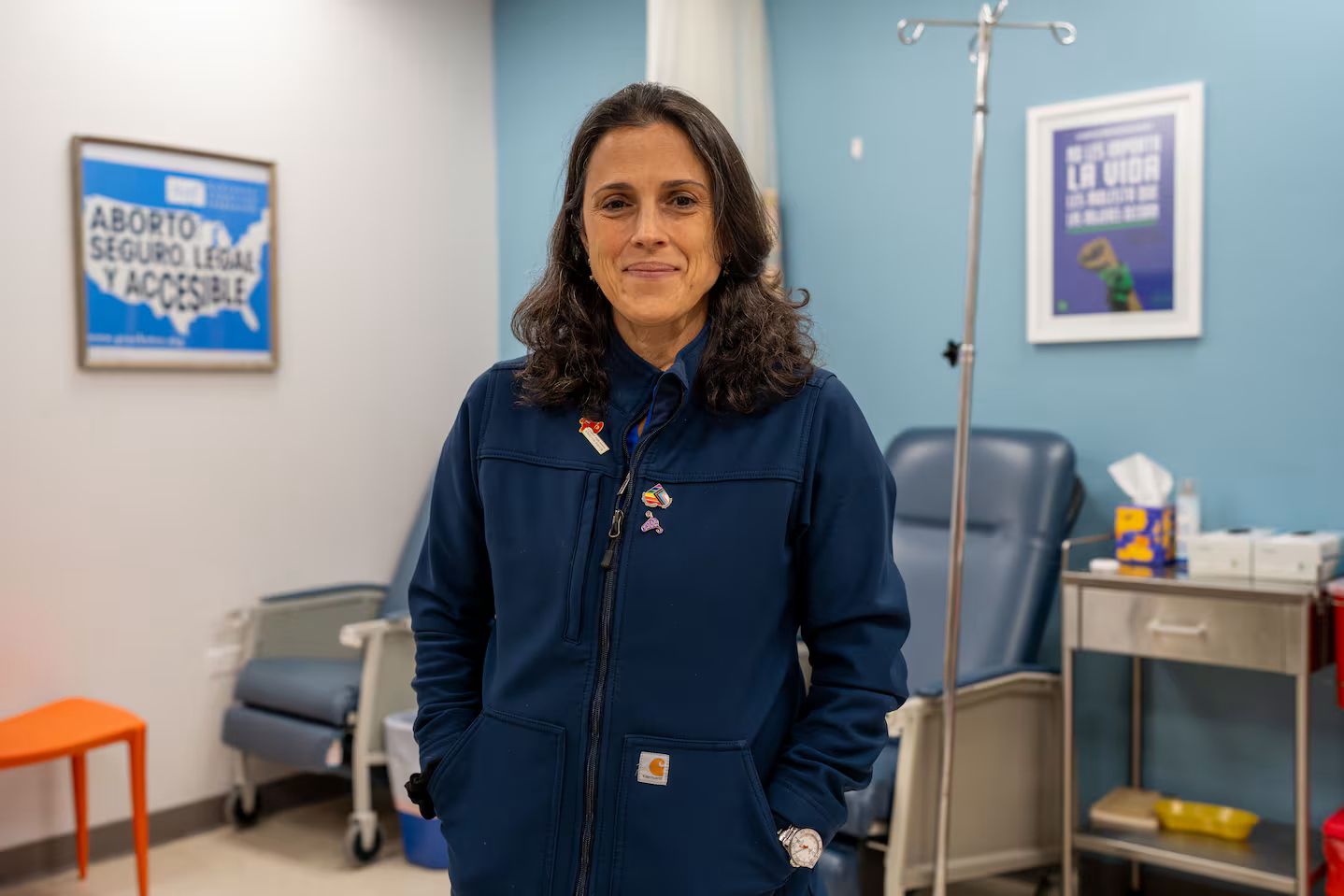

Dr. Yari Vale's petite frame is no longer weighed down by the nine-pound bulletproof vest she wore when anti-abortion threats increased after the end of Roe v. Wade, but she hasn't gotten rid of it. The security guard at Dr. Vale's Darlington Medical Associates clinic in Río Piedras is no longer at the door; still, she has him on standby. With the return of Donald Trump to the White House and Jenniffer González, a Trump devotee, in the governor’s seat, Dr. Vale is bracing for an escalation in the fight to safeguard reproductive rights in Puerto Rico.

The predominantly Catholic island is “on paper one of the most accessible places in the Western Hemisphere” to obtain an abortion, NPR reported just after Roe was overturned. But with the U.S.'s shift toward right-wing Christian nationalism, that could be changing.

Dr. Vale, an OB/GYN at the Darlington clinic—the only one of the island's four that does late-term abortions—is on the frontline of the fight to keep what’s happening in the United States from happening in Puerto Rico, euphemistically called an unincorporated territory (it's a colony, really). It's a battle that, she says, feels like “throwing a firecracker up in the air, and it's just smoke and no one hears you.” But she persists, knowing that the first line of defense is the clinics.

The Legacy of Pueblo v. Duarte

For years, Puerto Rico has been known for its liberal abortion laws: The right is enshrined in the island’s constitution (which exists separately from the U.S. Constitution) and is protected by the right to intimacy under Puerto Rico’s penal code. Abortion is legal on request if it is performed (or prescribed) by a physician to protect the pregnant woman’s life or health—and health includes mental health. There are no limits (abortion may not be banned before viability; post-viability abortions are permitted for the preservation of the pregnant person), and the procedure doesn't require the consent of partners, ex-partners, or, in the case of minors, parents.

However, these laws have their roots in a dark colonial history. In 1902, four years after invading the island, the U.S. enacted policies to control the population, although abortion was still prohibited without exception. Then, in 1937, colonialists who wanted to further limit the Puerto Rican population passed legislation based on racist neo-Malthusian and eugenic theories, virtually legalizing abortion on the island if it was to protect the life and health of the patient. These changes later facilitated clinical trials of the contraceptive pill and mass coerced sterilizations—a procedure that became so common that it was known among Puerto Rican women as “la operacion.”

In 1980, a case involving a minor and her doctor went even further, and set up modern abortion law in Puerto Rico. In the landmark Pueblo v. Duarte, Dr. Pablo Duarte Mendoza, who had performed an abortion on a 16-year-old girl in her first trimester, was sentenced to four years in prison. He appealed, and the Puerto Rican Supreme Court agreed with him, stating that through the island’s penal code, abortion is legal if it is performed to save the woman's life or health, including mental well-being.

Like many things on an island impacted by colonialism, abortion access is still limited for everyday Puerto Ricans. A surgical abortion costs $250, and a medication abortion between $300 and $350; meanwhile, about 43% of Puerto Ricans live below the poverty line, and insurance plans on the island do not cover abortion. And in addition to cost, religion and social stigma—the “what-will-my-family-say” factor—serve as deterrents for many women.

The Dobbs Effect

When 2022’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision removed the constitutional right to an abortion in the U.S., it didn’t automatically affect rights in Puerto Rico (unlike on the mainland, where “trigger bans” were in place). In fact, some U.S. women began to travel to Puerto Rico from states with restrictive abortion laws, such as Florida. It was the return of the “San Juan holiday.”

But Dobbs did embolden conservative Puerto Rican politicians and pro-life groups, who saw a window of opportunity and seized it. Shortly after the decision, the right-wing religious party Proyecto Dignidad (PD) adopted the U.S. anti-abortion lobby's blueprint and tried to push through several bills to curtail access to abortion, and even criminalize it. They argued that the end of Roe implicitly negated Pueblo v. Duarte. The Senate ultimately defeated the bills; according to many Puerto Rican legal experts, Pueblo v. Duarte rests on the Puerto Rican penal code, which has no analogy in the U.S. Constitution—and should, therefore, not be affected by Dobbs.

An Ascendant Right-Wing Movement

Abortion-rights advocates warn that efforts to criminalize abortion in Puerto Rico are not over. Traditionally, “the issue of abortion in Puerto Rico has not been the overriding controversy that the anti-abortion and ultra-religious politicians want to make it out to be now,” says Senator Maria de Lourdes Santiago, a lawyer and Senator for the Puerto Rican Independence Party (PIP). But, she says, the anti-abortion campaign orchestrated by Proyecto Dignidad now "magnifies the issue to demonize it."

Founded in 2019, PD has capitalized on its nexus of Catholic and Evangelical churches; the erosion of the traditional duopoly of the pro-statehood New Progressive Party (PNP) and the Popular Democratic Party (PPD); and an increasingly ultra-conservative sector of the population urging a return to traditional values. Even though the party got only seven percent of the vote in the 2024 elections, its influence is strong island-wide, with a campaign that now hinges on the abortion issue.

Proyecto Dignidad Senator Joan Rodriguez Veve, a canon lawyer and face of the populist religious right, has vowed to continue fighting to restrict access to abortion. She recently introduced legislation, PS 297, restricting access to abortion for adolescents under the age of 15. The bill is a carbon copy of one that the Puerto Rican House rejected a year ago. It calls for jail time for any doctor or person who assists a minor in getting an abortion, and a slew of other measures, including forensic interviews of minors seeking an abortion.

The Senate approved the bill in February, and almost everyone I spoke to—politicians, legal experts, and abortion doctors—told me they believe it will pass, even though both pro-abortion and some anti-abortion groups have, for different reasons, voiced their opposition to the measure.

A New Generation Stands Up

At the same time that PD is gaining influence, attitudes about abortion are shifting with the younger generation. Rising numbers of people support abortion rights, and young people have galvanized around the issue, taking to the streets in protest and amplifying groups like Aborto Libre Puerto Rico, Profamilias, and Proyecto Matria, among others. It’s a generation that, unlike its mainland counterpart, grew up without a sense of abortion as a wedge issue.

Most recently, health professionals and activists have spoken out against PS 297, warning that the bill puts women and girls in danger. “What's going to happen here is that young women and those most vulnerable will seek out illegal abortions and go to the places where illegal drugs are sold to purchase abortion pills, many cut with fentanyl, in doses that are not recommended,” says Puerto Rican feminist activist Alondra Hernández Quiñones.

As religious and conservative groups gain traction in Puerto Rico, Dr. Vale worries that a girl of 15, whose parents are ultra-conservative and refuse to consent to her abortion (as the new legislation would require), would be forced into motherhood. Clinics like Darlington have stopped seeing patients younger than 15 at all, and Dr. Vale fears a future where abortion, currently a safe and regulated procedure, “will once again be a public health problem…where we don't know how many women end up in emergency rooms due to an [unregulated] abortion gone wrong.”

“This worries me a lot,” says Isharedmie Vazquez, a 17-year-old Puerto Rican student. “It seems incredibly wild to me that instead of guaranteeing secure options [for an abortion], what they are looking for is to criminalize it and force women to assume a responsibility for which they are not prepared. It's unfair that they want to take away the right to decide about our lives.”

Susanne Ramírez de Arellano is an author on race and diversity, opinion writer, and cultural critic. The former news director of Univision, she writes for NBC News Think, Latino Rebels, and Nuestros Stories, among other outlets.

Susanne Ramírez de Arellano is an author on race and diversity, opinion writer, and cultural critic. The former news director of Univision, she writes for NBC News Think, Latino Rebels, and Nuestros Stories, among other outlets.