The “Recurring Lies” We Learn in School

As our country marks Black History Month by banning books about race from classrooms, writer Eve L. Ewing looks at the long, complex “miseducation” of Black and Native children.

BY REBECCA CARROLL

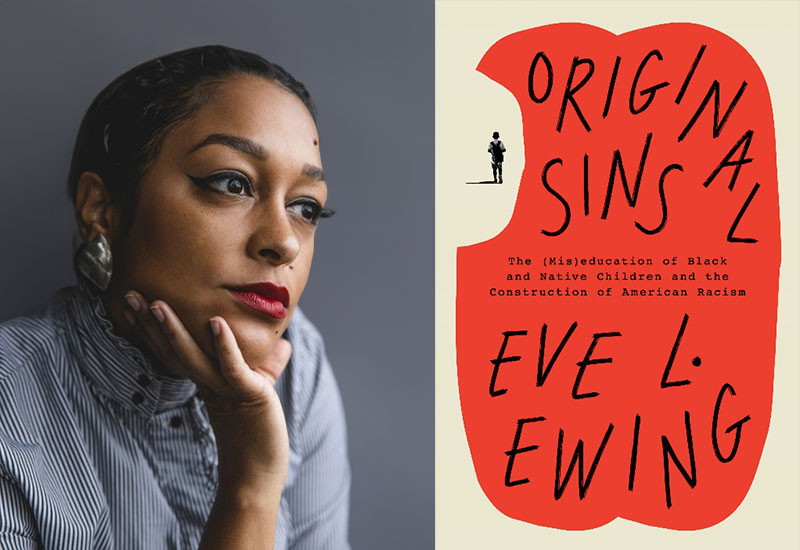

AUTHOR EVE L. EWING WANTS YOUNG PEOPLE TO “UNDERSTAND THEIR OWN RADICAL POWER.”

It’s been less than a month of the second Trump administration, and already in its crosshairs is the Department of Education. Trump has pledged to abolish it, issued an executive order threatening to defund schools engaging in discussions around race and oppression, and has empowered Elon Musk, a white male billionaire who grew up under the racist apartheid system of South Africa, to cancel $900 million in research grants. If there is a next level of “hope,” we need it now—and no one embodies hope, especially when it comes to education, more than poet and scholar Eve L. Ewing. Her new book, Original Sins: The (Mis)education of Black and Native Children and the Construction of American Racism, approaches the issue of disparity in education—specifically for Black and Native students—with the revelatory question of, “What if American schools are doing exactly what they are built to do?”

From the earliest efforts to offer schooling to formerly enslaved Black people—efforts that were met consistently with questions of whether or not Black people were human enough to be educated—to the compulsory boarding school attendance of Native children with the aim of “civilizing” them, Original Sins unearths the DNA of America’s education system, and lays bare the ways in which our knowledge has “been impacted, and to some degree, severed by colonialism.” And as Trump cuts DEI initiatives in American universities and colleges, one note from the book resonates: Schools, Ewing writes, “have never been for us.” But, she continues, regarding the education system as a whole, “The good news is that people made it, and people can unmake it—and make new things.”

Rebecca Carroll: It seems that from the start, the educational attitude toward Black folks was: We’ll give you subpar resources, but will (mostly) leave you alone as long as you stay away from us (white folks). While for Native Americans, it was: We’re going to steal your children, and destroy all their cultural ties to you. Why were the educational strategies used against Black folks and Native Americans so different from one another? Or were they?

Eve L. Ewing: The United States was founded on land that was violently stolen from the Native people who had lived here since time immemorial, and that land was tilled by enslaved Africans who were stolen from their homelands, degraded, and treated as property. Those foundational thefts enriched the nation at the expense of the lives, land, and dignity of Black and Indigenous peoples. And those actions didn’t happen in one discrete moment—they continue to reverberate in the world we live in today.

So in order for the country to sustain itself, it has required an intellectual underpinning that justifies those evils. It requires a set of recurring lies, to make it all seem okay. And that’s where schools come in: a place to make the lies seem real. Three of those lies that I talk about in the book are: the lie that Black people and Native people are intellectually inferior, the lie that our bodies and our children’s bodies inherently require more discipline and control, and the lie that we are destined for economic subjugation, that it’s our fate in life to lie at the bottom of a capitalist hierarchy.

There are ways that anti-blackness and anti-indigeneity use the same weapons, but there are indeed ways that the strategies diverge. And the reason for that is that white supremacy has historically needed different things from us. It has needed Black people to be subservient, and it has needed Native people to be gone. That’s how I would put it simply.

RC: What do you think is the responsibility of educators who began their careers when the official default was white supremacy? Is there a process of undoing (not a punishment) that needs to occur for teachers of all races who, for perhaps decades, taught children of all races through the lens of racial hierarchy?

ELE: It’s a hard question. I think it’s important to begin by centering ourselves in relationships. All of us—in our personal lives, in our work lives—have had moments when we thought we were doing our best, and it’s made clear to us that the people we loved were not served by our choices. When that happens, we have a choice to make: Do we choose to be defensive, or do we take the opportunity to be reflective? If someone takes the time to try to teach you to do better, to be better, that’s an act of love. Are you able to receive that love, or not? Are you able to be accountable for your actions? That’s a question for folks to ask themselves. At the same time, we need to be making space for people who are radically caring and transformative to enter the profession.

RC: Speaking of undoing racist teachings, you cite the work of scholars Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, who disparage the “easy use” of the word “decolonize.” They note that in recent years, social justice activists have suggested “decolonizing” certain spaces and ideology…but in doing so have actually trivialized the word. Is it not possible, though, for an easy use of a term to also be effective?

ELE: I think the question has to be, effective for what? …Real decolonization is not easy, and if a violent colonial institution continues to profit from harms against Indigenous peoples, having a single book or training or workshop or affinity group and then saying that that is “decolonizing” could be not only misleading—it could be actively dangerous, because it gives people a facile representation of what decolonization is. It reminds me of a moment in 2020 when the university where I work declared that they were committed to anti-racism, which could not have been further from the truth. So I see it as less of a scholarly conversation, and more of a “say it with your chest” conversation, or a “don’t just talk about it, be about it” conversation.

RC: In a recent piece for In These Times, you wrote: “It’s not enough to be afraid of the laws and rules we don’t want to see in schools.…Who are the young people you love most….What are the values you hold dear that you want desperately for them to understand, to inherit?” To your young beloveds, or simply to your readers, what are the values you hold dear that you want desperately for them to understand, and to inherit?

ELE: Thank you for that question! I want the young people in my life to understand their own radical power to love: to love themselves, to love others, to love the lands and waters and more-than-human relatives, and to understand how strong we are collectively when we turn that love into action. I want them to voraciously seek out stories in all forms and to see themselves as storytellers. And I want them to understand Chicago history and the history of great Black artists who shaped culture as we know it.

Rebecca Carroll

Rebecca Carroll is a writer, cultural critic, and podcast creator/host. Her writing has been published widely, and she is the author of several books, including the memoir Surviving the White Gaze. Rebecca is Editor at Large for The Meteor.