Courage and cigarettes

Iran

January 15, 2026 Greetings, Meteor readers, My kid is getting her tonsils taken out this week. Any parents out there with tips on how to survive the recovery period, I welcome the guidance. On to bigger things. In today’s newsletter, protests in Iran have already reached a terrifying death count. Plus, the government is investigating Renee Nicole Good’s widow instead of focusing on her killer. Popsicles for the apocalypse, Shannon Melero  WHAT’S GOING ONA history of resilience: At the end of December, shopkeepers and business owners in Tehran shut down their stores and took to the streets in protest. Within hours, a chant at the heart of the protest had spread across the city: “Our money is worth less.” What began as a localized economic complaint has grown into a nationwide anti-government protest that has reportedly claimed the lives of thousands of Iranians. To outside observers—especially those of us caught up in our own country’s headlines—this was a startling escalation. But for those living and working in Tehran, the writing was on the wall for some time. The Iranian economy has been in crisis mode for months: sanctions from the U.S., a 12-day war with Israel, water shortages, and in December—apparently the last straw—Iran’s currency, the rial, hit an all-time low. In an initial response to the protests, the Iranian government offered a monthly stipend to alleviate financial woes that was equivalent to seven U.S. dollars. It was an insulting band-aid. And as protests continue, Iran’s leaders have resorted to suppression and violence, attempting to keep Iranians quiet with internet blackouts, imprisonment, and murder by officials of the regime. And while all Iranians are suffering as a result of economic and political instability, this is yet another situation in which women will suffer the most. A UN Women report from 2024 found that Iranian women are more than twice as likely to be unemployed as men. In times of political upheaval, those numbers—along with sexual and physical violence against women—are expected to worsen. We have all seen this before. Time after time, the Iranian people have risen up against their leaders despite being met with the cruelest response. In 2022, after the killing of Mahsa Amini, which sparked the Woman, Life, Freedom movement. In 2021, over water shortages. In 2019, over fuel prices. In 2009, over questionable election results. But some Iranians who spoke to the New York Times said that these protests felt more powerful than even those of 2022 because they have captured Iranians from all walks of life. Young women have been front and center; the internet is full of images of Iranian women using burning pictures of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to light their cigarettes. Conservative and rural Iranians—who for the most part remained on the sidelines during the Women, Life, Freedom movement—are making themselves heard now. “We can see from the news and from some government reactions that this regime is terrified to its bones,” one protester in Tehran told a Times reporter. Many in the streets, on the other hand, are projecting fearlessness. “We are not afraid,” said Sarira Karimi, a University of Tehran student who was arrested last month, “because we are together.” The Trump administration has been keeping an eye on the situation, and earlier today, the president suggested that he was open to an airstrike, writing on Truth Social that the U.S. was “locked and loaded” and that “help was on the way” for protesters (excuse us?). He added that the military was reviewing “some very strong options.” No mention yet if Trump intends to be the acting president of both Venezuela and Iran, but it wouldn’t surprise anyone. AND:

PROTESTORS IN MINNEAPOLIS THE DAY AFTER GOOD’S MURDER (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

OF COURSE THE GAY SHEEP ARE SERVING LOOKS TO THE CAMERA (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

They Were Told “Don’t Write, Don’t Post, Don’t Report”

For Iran’s fearless women journalists, every byline is a form of rebellion

By Tara Kangarlou

“To be a war correspondent is like a wounded dove flying through a pitch-black tunnel. It crashes into the walls over and over, but keeps going, for a chance to send the message, to save others,” says Arameh, a 40-year-old Iranian journalist. She and her two colleagues, Samira, 39, and Parvaneh, 27 (all have been given pseudonyms for their safety), are among the many brave Iranian journalists who remained on the ground in Tehran to report on the 12-day Israel-Iran war earlier this summer.

The women work for one of Iran’s prominent news sites, covering social, local, and political issues. Although the outlet is independently owned, it still falls under the heavy scrutiny of the Islamic regime’s watchful eyes. (Out of the utmost caution, we’ve withheld the name of the website.) “Despite slow internet and censorship, we wrote, posted, and published” throughout the war, recalls Arameh. “With images of blood and death flooding in, we kept reporting.”

Ultimately, Iran’s missile attacks on Israel killed 28 people and wounded more than 3,000, some of them civilians. Israeli airstrikes on Iran killed more than 1,190 people and injured 4,475, according to the human rights group HRANA. As in many conflicts, Western coverage of the war zeroed in on geopolitics: the Islamic Republic’s hardline rhetoric, the regime’s nuclear ambitions, and the fate of a theocracy teetering on the edge. Yet beneath those soundbites, a generation of fearless, tenacious young journalists—many of them women—tirelessly documented life under foreign bombardment and domestic censorship in the world’s third-largest jailer of journalists.

According to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), more than 860 journalists have been arrested, interrogated, or executed in Iran since the 1979 revolution, which brought the Islamic Republic to power. RSF also reports that since Mahsa Amini’s killing in September 2022, at least 79 journalists, including 31 women, have been detained—with some still behind bars. The International Federation of Journalists and Iran’s own Union of Journalists report even higher figures, estimating that over 100 journalists have been detained during this period, most in Tehran’s notorious Evin Prison. Among those held were 38-year-old Elaheh Mohammadi, her twin sister Elnaz, and Niloofar Hamedi, who first broke the news of Mahsa Amini’s killing for Shargh Daily in September 2022.

My connection to these women goes beyond our shared profession—I was born and raised in Iran and immersed in all the complexities of its everyday life; but today, as an American journalist with dual nationality, I can no longer return freely to my country of birth—simply because my profession is deemed threatening to the forces at home. I often have nightmares of being arrested in Iran or of never again seeing my childhood home; but what gives me hope is the strength of women like Arameh, Parvaneh, and Samira, who stayed. They do so knowing their government is always watching, listening, and ready to punish them for telling the truth.

These women were not just covering a war; they were surviving it.

On the war’s second night, 27-year-old Parvaneh tried sleeping in the newsroom as her home was in an evacuation zone. It was just her and the office janitor, whose pregnant wife and daughter had already left the city after their neighborhood was hit. That night, Parveneh recalled, “the sirens were so loud that neither one of us could sleep, so I stayed up all night and covered the strikes.”

On day three, Arameh convinced her aging parents, brother, sister, and five-year-old niece to leave Tehran without her. “With each strike, I’d tell my niece it was a celebration or fireworks,” she recalls, heartbroken that the little girl believed her each time.

Similar to many other journalists and photographers in the country, Arameh and her colleagues received anonymous calls from intelligence agents and government officials warning, “Don’t write. Don’t post. Don’t report.” But as always, they did. Samira reassured her mother, whose brother was killed in the Iran/Iraq war in the 1980s, that she would not leave Tehran. “I’m a journalist,” she explains. “If I’m not here in these days, it would be like a soldier abandoning the battlefield.”

“We adapted; we always do,” Arameh says. “We stopped giving exact locations or numbers. Instead, we reported where sirens were heard. We told people how to protect their children. In times of war, a journalist must also be a source of empathy.”

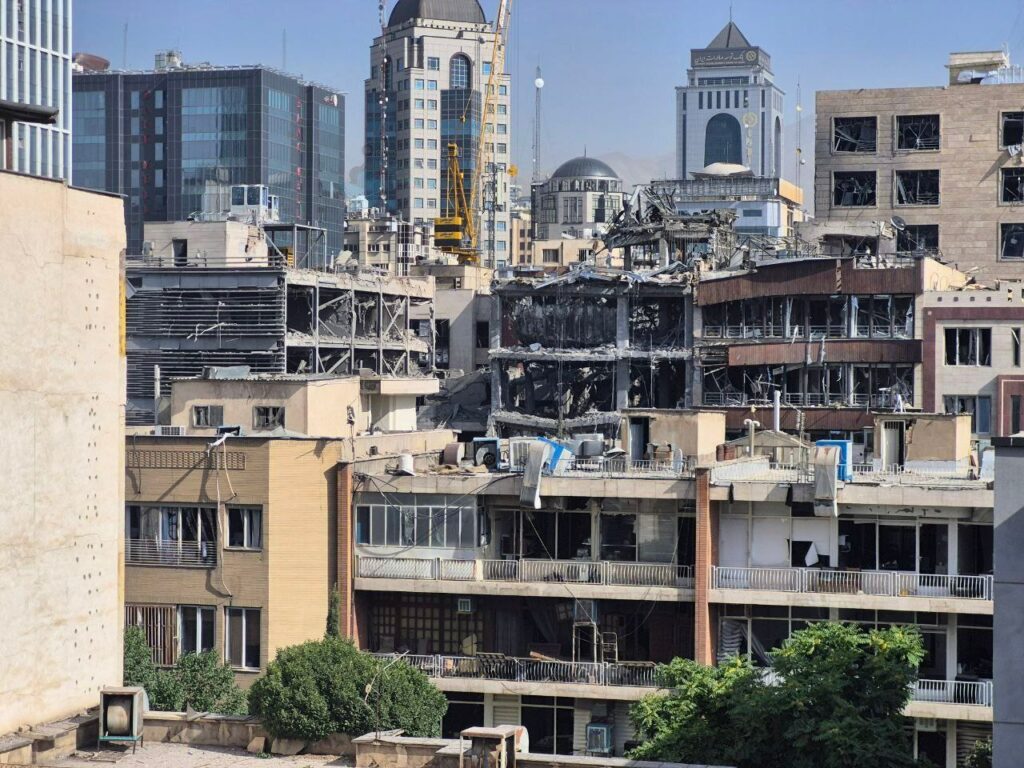

For journalists in Iran, adaptability is a necessary skill as they navigate censorship, surveillance, and threats from a regime that has long waged war on its own press. These women documented both the human devastation of the war—including the Tajrish Square bombing that left 50 dead—but also the ongoing intimidation from the state toward members of the press. That intimidation extends to those who defend journalists as well. Human rights lawyers such as Nasrin Sotoudeh, Taher Naghavi, and Mohammad Najafi have been imprisoned for the “crime” of representing journalists and activists.

“My beautiful Tehran felt like a woman who had been brutally violated; battered, broken, bleeding,” says Samira, recalling the last night of the war. “It was the worst bombardment; something inside us died, even as the ceasefire began.”

On June 23, just one day before the ceasefire that would end the war, Israeli airstrikes hit Evin, killing at least 71 people—among them civilians, a five-year-old child, and political prisoners, including journalists. Nearly 100 transgender inmates are presumed dead—all people who should never have been there from the start.

The world often celebrates Iranian women in hashtags and headlines, but falls silent when it comes to tangible support. Heads of state, renowned public figures, and human rights organizations call for freedom and justice, but political inaction persists.

“If such strikes happened elsewhere—especially Europe or the U.S.—the world would’ve cried out,” Arameh says. “But in Iran, the Iranian people are always defenseless. People around the world talk about loving Iranians, but…we are once again left alone in our pain.”

Iranian journalists are not asking to be saved. They are asking to be heard, to be respected as the only eyes and ears of millions whose voices have been stolen by a regime that does not represent them. More than anything, these independent journalists, who are not funded by the regime and continue to report under severe censorship and surveillance, are emblematic of a deeper reality: that Iranians—especially women, and especially young people—stand firm in their pursuit of truth, change, and growth, no matter the cost.

Tara Kangarlou is an award-winning Iranian-American global affairs journalist who has produced, written and reported for NBC-LA, CNN, CNN International, and Al Jazeera America. She is the author of The Heartbeat of Iran, an Adjunct Professor at Georgetown University and founder of the NGO Art of Hope.

Iran Temporarily Releases Narges Mohammadi

December 5, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, It’s the least wonderful time of the year—and by that, of course, I mean Spotify Wrapped season. We get it, you’ve got great* taste in music. (*Editor’s note: This does not apply to all of you.) In today’s newsletter, we stand in awe of Narges Mohammadi and catch up with the Court’s big day yesterday. Plus, your weekend reading list. Wrap literally anything else, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONNobel laureate and Iranian human rights activist Narges Mohammadi has been given a three-week medical release from prison in Tehran. Mohammadi has been in and out of prison for decades and, since 2021, has been serving a 13-year sentence on charges of “spreading anti-state propaganda” for her work in Iran’s women’s rights movement. As she was being wheeled out of an ambulance on a stretcher after her release, without the required head covering, Mohammadi shouted the movement’s slogan: “Woman, Life, Freedom!” Mohammadi has suffered several health issues during her imprisonment, including multiple heart attacks and, most recently, an emergency surgery to remove a cancerous tumor. After her leave, the state expects her to continue her imprisonment in Evin Prison. Mohammadi’s lawyers and the international community all believe that her continued imprisonment is inhumane and a violation of Mohammadi’s rights. MOHAMMADI AFTER HER RELEASE HOLDING A PHOTO OF MAHSA AMINI. WRITTEN ON HER HAND IS "END GENDER APARTHEID" IN FARSI. (IMAGE VIA INSTAGRAM) Despite the severe crackdowns on public gatherings since the Mahsa Amini protests shook the nation two years ago, Iranian women have continued the fight against their theocratic government, which has in turn intensified punishments against them. Iran's Hijab and Chastity bill—which will punish both women and men for “improper dress” by issuing fines, blocking country exit permits, and, in some extreme cases, imprisonment—will go into effect next week. As Mohammadi recovers at home and continues to speak out for Iranian women, we are reminded of the words she wrote while still imprisoned: “Victory is not easy, but it is certain.” AND:

WEEKEND READING 📚On challenging the norm: For the last 50 years, one feminist magazine you may have never heard of has been pushing back on Mormon tradition. And it’s written by Mormon feminists. (High Country News) On asking and telling: Trump’s return to office has stirred up concerns about the resurgence of anti-LGBTQ+ “witch hunts” in the military. (The War Horse) On paying up for postpartum care: Retreats for new moms, which have long been the norm in parts of Europe and Asia, are popping up in the U.S. But at an astonishing $1,000 per night, are moms and babies getting what they’re paying for? (The Cut) On your speakers: The latest episode of America, Who Hurt You? dives into the lesser-known history of Muslims in America. (Apple podcasts)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Voices From Inside Iran's Freedom Movement

Iran

Mahsa Amini's death was only the beginning

By Gelareh Kiazand

Today marks exactly a year since the death of Mahsa “Jina” Amini, a young Kurdish woman who had been detained by what’s known in Iran as the Morality Police for “improperly” wearing her hijab, and who went into a coma while in custody and died shortly after. Despite the government’s attempts to cover up the circumstances of Amini’s arrest, pictures of her in the hospital and the eventual news of her death sparked massive protests and set the Woman, Life, Freedom movement in motion, the scale of which took many by surprise. Tens of thousands of people spilled into the streets in around 100 cities, in an explosion of suppressed pain over years of censorship, patriarchy and government coverups.

The government harshly retaliated: It’s estimated that in the first six months of the protests, more than 500 police and protesters were killed, 20,000 people arrested—and at least six executed. Internet access was disrupted in an attempt to suppress the protests.

The brutality and murders did scare some people off the streets. By January, many acts of defiance had migrated to social media, where high school girls were dancing, removing their headcovers, and pulling down the pictures of government officials, including the supreme leader Ayatollah Khamenei. Soon, people began reporting cases of school poisonings that ultimately affected more than 1,000 girls, most suffering from breathing problems. Even though the government arrested those who carried out the so-called “nitrogen” gas poisonings, many parents suspect authorities were involved, or at the very least looked the other way.

In April, the streets of Tehran were again filled—this time with women not wearing any form of hijab, in violation of national law. The government started issuing economic fines to celebrities, business, and ordinary citizens. Small cafes with customers who refused to cover became prime targets of police harassment and closures. Around 150 businesses were shut down.

As the anniversary of the protests approached this summer, authorities are still arresting, intimidating, and threatening protesters and their families. Niloufar Hamedi and Elahe Mohammadi, the two women journalists who first reported on Amini’s death, are still under arrest and awaiting trial with charges of espionage. Seventeen more journalists remain detained.

Whatever comes next may make history. The government has taken no steps to address the movement’s cries of injustice, and President Ebrahim Raisi, who won in a highly engineered election with the lowest turnout on record, hasn’t improved Iran’s struggling economy. But voices seeking to topple the regime, both on the ground and online, have only grown louder.

Women have always been a political force in Iran. We spoke with several of these women (and one man), all of whom have been profoundly affected by the past year’s uprising. All of them have been given pseudonyms to protect their identities.

Pardis, 24, runs her family’s small cafe in Tehran. During the peak of the uprising, she sheltered injured and runaway protesters. The authorities ordered her to refuse the protesters or be arrested. She chose the latter, and was taken to prison for 24 days.

“If anyone can change this situation, it is the people of Iran. Look, I was not a political person at all; I was thinking about parties and boys and these things. I went to prison because of my beliefs—it’s ridiculous to be afraid now. They are forcing us to show a reaction to the killing of Mahsa Amini, which was not even justified. Why should teenagers be killed? I was living my life, but after these events, how can we remain silent? [The movement] has changed everything, in my opinion. Even the most distant people, the most religious people, whether they like it or not, are affected by this revolution.”

Ameneh is a 28-year-old woman from Zahedan, Baluchistan, a conservative and underserved province that was one of the country’s most active areas during the uprising. Her family prohibited her from continuing her studies at a young age, and never let her venture far from her home city. The uprising was the first time her family allowed her true independence.

“Here, the conditions are again like those first weeks. The city is very controlled. People’s phones are checked. They are very sensitive to the anniversary and scare the people so they don’t come out. People have no right to participate in the rally and the mosque.

“From the first day, [prominent Sunni spiritual leader] Molavi Abdul Hamid criticized the killing of Mahsa Amini. The people of Zahedan are very fond of Molavi and they also supported him. [As a result] Friday prayers were and still are strictly controlled, and they even put checkpoints in the city a day or two before. My brother was arrested by intelligence forces in mid-November [for being] a member of mosque security and the liaison to deliver medicine to the injured people of Zahedan’s Bloody Friday. Later they attacked our house many times and searched and took all my brother’s belongings. At that time, one of our acquaintances said that these drugs should be brought from Tehran, but it was very risky. Finally, I decided to go to Tehran and bring these medicines.

“[Growing up] I really wanted to study or dress the way I like, but it was impossible. At that time, when I said I wanted to do this, I was alone, there was no one to support me, there was no other girl like me. But now I don’t feel alone anymore and I have more courage. I see this change in both women and men.”

Soha is a 17-year-old student who is religious and attended the protests with a headscarf. For her, the movement was about standing for the freedom of women, who should not be defined by hijab. Her mother, Mitra, 54, who also is religious, joined her in the protests.

Soha: “I have never been insulted by people who don’t believe in hijab. But I have seen many times that girls who don’t wear a headscarf are insulted or made to feel insecure by the morality police or by women who are hired by the Islamic Republic to intervene in the issue of hijab.”

Mitra: “As a Muslim woman, I cannot allow them to kill people under the pretext of my religious beliefs. In my opinion, the Islamic Republic is not only not Muslim, but [also] fueling anti-Islamism. In the religion of Islam, it is not said to keep people hungry and to keep the hijab. Islam does not say kill or imprison anyone who disagrees with you. Hijab is important in Islam, but not as important as a person’s life. Was there a problem with [Amini’s] hijab from the point of view of Islam?”

Soha: “The new wave of the movement will start soon, and in my opinion, religious people will play a big role in this new wave.”

Mehdi, 19, is a student in Tehran. At the rallies, he witnessed his friend getting shot, and he himself was beaten by the security forces. He and his friends believe the forced ruling of “old men” needs to end.

“In 2009, I was very young, but I understood that people were protesting and I saw that they were being suppressed. At that time, my family was not against the Islamic Republic and my father even worked in the Revolutionary Guards, but he had seen things up close that had an impact on him, and since then, his perspective changed. So he resigned from his job. Many people who thought that the Islamic Republic had no problems realized that they were on the side of corruption. People see that this government is only lying to them and this is no longer acceptable to many. My father always said that if anyone can oppose the [clerics in the Islamic republic], it is women.

“People want stability. They want a good economic situation. A few nights ago, one of my friends told me to go to the embassy for immigration. I said that the future is here; we just have to build it.”

Rana, 35, is a teacher from Kurdistan, the province where Amini is from. Kurdistan, like Baluchestan, faced some of the harshest crackdowns. Doctors were working secretly in people’s basements to help the wounded. Many homes were open to neighbors so the community would not be weakened.

“In Kurdistan, I feel the meaning of women is different than in the rest of the country. They are raised as fighters, live as fighters, and die as fighters. Because we as Kurds have always fought for our ethnicity, this seems to have been born within the women. The slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom” [signifies] a freedom of humanity which shouldn’t be defined by what is worn or not worn. It is the freedom…of choosing who I am, bearing its responsibilities, and shaping my life through that. I feel the women of Iran are finally starting to understand what freedom can hold.”

Gelareh Kiazand is a Canadian-Iranian based between NYC and Toronto who has worked in Iran’s film and documentary industry for 12 years as well as covering stories in Afghanistan and Turkey. In 2016, she became Iran’s first female DoP for a fiction feature film, post-’79 revolution.

Don't Stop Posting About Iran

|

Salutations, Meteor readers, It’s our least favorite day of the week: Monduesday, the Tuesday after a 3-day weekend. Yes, it’s a word, and I’m determined to make it happen. But as always, it is good to be in your inbox once again bringing you something special. Last week, we wrote about the ongoing execution of protestors in Iran. One question we had not seen addressed: In a revolution sparked and led by women, why is the Iranian regime choosing primarily to sentence men to death? We asked Sherry Hakimi, policy advisor and executive director of genEquality, to help us better understand what’s going on. But before that, a little news. With love, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONLeading Against White Supremacy: Texas representative Sheila Jackson Lee introduced a bill last week, H.R 61, that seeks to “prevent and prosecute white supremacy-inspired hate crime” as well as expand the scope of what is considered a hate crime to begin with Seems reasonable! And yet Republicans immediately framed this bill as an attack on the First Amendment. Lauren Boebert literally called it a mockery. Here’s why that doesn’t make sense: First of all, according to the FBI, there were over 4000 racially motivated crimes reported in 2021—so the suggestion that something be done about them isn’t coming out of left field. Second, Lee’s bill doesn’t suggest an overhaul of how free speech works, it simply looks to include specific language into existing laws surrounding hate speech that would criminalize conspiracy to commit a white supremacist hate crime, meaning even if you personally don’t do a hate crime but you post something that inspires one, you can still be held culpable for the crime. We should be calling this the name-the-devil-for-what-he-is bill. Still a little confused? Don’t worry, so was Boebert. This bill would not send your Uncle Rob to jail because he posted a racist-lite meme on his Facebook page. But it would give the government clearance to investigate your little cousin Rich who has been consistently posting about how much he hates the mosque down the street on a Reddit sub-thread about white nationalism and replacement theory. See the difference? Yes, it’s 2023: ICYMI, last week Missouri’s House of Representatives used their limited time on earth to update their dress code—but only for women lawmakers, who are not allowed to wear anything sleeveless. And before you check to see if that last link goes to The Onion, this REALLY happened. The updated rule states that the “proper attire for women” consists of trousers, skirts, or dresses worn with jackets and blazers. Cardigans are also acceptable for the fashion girlies. The debate over this rule (yes, a serious debate between adults) ranged between what qualifies as a jacket or blazer, whether or not knit blazers were acceptable, and if certain fabrics would disqualify said jackets and blazers. As Missouri state Rep. Ashley Aude told CNN, “On day one in our legislature, they’re doubling down on controlling women.” (Friendly reminder that it’s always a good day to run for office.) AND:

FOUR QUESTIONSWhat We All Need to Know About the Executions In Iran“This is androcide.” BY SHANNON MELERO  PROTESTORS IN ITALY DISPLAY AN IMAGE OF ONE OF THE MEN EXECUTED BY THE IRANIAN REGIME. (IMAGE BY STEFANO MONTESI VIA GETTY IMAGES) Just three days ago, Iranian news agencies confirmed the execution of another man. As far as reliable sources are able to confirm, he appears to be the 33rd person executed by the state in 2023. As the regime continues to crack down on protestors who have taken to the streets after the death of Mahsa Amini, I spoke to Sherry Hakimi, policy advisor and executive director of genEquality about what’s really happening—and what, if anything, we can do. Shannon Melero: What exactly does the international community need to know about the executions of protestors happening in Iran? Sherry Hakimi: The Islamic Republic has long used execution as a violent tactic for suppressing dissent. Even before the recent revolutionary movement, executions had been rising in Iran: In 2022, the number reportedly surpassed 400 before the September protests began; in 2021, there was a 20% increase in executions over 2020, mostly on drug-related offenses. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, these executions break international human rights law by violating due process and fair trial guarantees. The violations include the use of vaguely worded criminal provisions, denial of…the right to present a defense, forced confessions obtained through torture and ill-treatment, failure to respect the presumption of innocence, and denial of the right to appeal. What are these people being charged with that is so severe their government believes it warrants death? To be clear, these are charges made in sham judicial processes. Currently, the common charges are murder of [Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps officers], “moharebeh” (“waging war against God”), and “mofsed-e-felarz” (“corruption on earth”). The people who have been executed to date have been found guilty of murder on the basis of what can only be called coerced confessions. As for “moharebeh” and “mofsed-e-felarz,” these are catch-all charges that the Islamic Republic often levies on anyone who goes against them. It’s important to recognize that from whatever angle you look at it—judicial, political, social, moral—these executions are illegitimate and must be stopped. Is there a reason that the executions we’re aware of have been men? I think in general we understand that this revolution began with and about women, and yet that’s not who we are seeing receive these harsh punishments. First, I have to disagree with the implication that women aren’t receiving harsh punishments. There are reportedly more than 19,000 people currently held in Iran’s jails, and there have been numerous reports of Iranian women being brutally beaten, tortured, raped, disfigured, and murdered by regime forces. Going through a sham judicial process before being brutalized or murdered does not lessen the harshness of either. The atrocities experienced by women—namely, brutal rape and sexual assault—are violent, gruesome atrocities that will haunt and adversely affect those women for the rest of their days, leaving them psychologically, emotionally, and often physically scarred. I am in no way diminishing the severity of execution, but rather, elevating the severity of rape and sexual assault to the level at which it should be considered. Both execution and rape are unacceptable and inhumane tools of war utilized by primitive brutes. These acts have no place in today’s world. A few points come to mind as to why we’re seeing more men face execution. First, there’s very little (if any) reason to believe a single one of the charges levied against any detained protester, but the four men who have been executed to date were all charged with murder. It’s possible that the Islamic Republic, in keeping with its patriarchal ways, thinks it is somewhat more plausible to pin false murder charges against male protesters. Second, although Iran is one of the world’s biggest perpetrators of the death penalty (second only to China) [with] the distinction of having executed the most women to date, women generally make up a small percentage of the people who are executed each year everywhere. (According to the Death Penalty Information Center, women make up 1.2% of the people who have been executed since 1976 in the U.S.) It’s possible that we’re seeing a similar dynamic play out in Iran. All protesters and detainees face brutal and indiscriminate beating and torture. Women disproportionately experience brutal assault and rape, and men disproportionately are handed execution sentences.  PROTESTORS TOOK TO THE STREETS OF ISTANBUL EARLIER THIS MONTH TO TAKE A STAND AGAINST THE REGIME'S EXECUTIONS. (IMAGE BY OMER KUSCU VIA GETTY IMAGES) Third, this is indeed a female-led revolution, but the protesters are not solely women. From the beginning, we have lauded the fact that Iranian men and boys have been out there, shoulder to shoulder, protesting alongside Iranian women and girls. Lastly, it’s likely not an accident that the four men executed to date and the dozens of others who face imminent execution include a karate champion, a bodybuilder, a doctor, a popular rapper, etc. In instances of war and conflict, both international and domestic, there is a history of aggressors targeting strong, skilled men and boys. This is androcide: when one side of a conflict sees its opposing men, fighting or otherwise, as rivals and a threat to their superiority and thus sets out to kill the rivals and neutralize the perceived threat. Frankly, only a country led by weak and insecure brutes treats its own people as the enemy and wantonly subjects them to violence and death. Is there anything people outside of Iran can do to help? Is there something specific the American government should be doing? This revolutionary movement is ongoing, and the plea of Iranian protesters is for everyone outside of Iran to be their voice. To that end, one of the most helpful things that people can do is to keep posting about Iran across their social media channels. This is the rare case in which posting about an issue on social media is not “slacktivism,” but rather, proper activism. You can also join protests, speak with friends about what’s going on in Iran, and generally use every opportunity to spread awareness of the Iranian people’s fight for women, life, and freedom. Revolutions are unpredictable, but the Islamic Republic regime is unlikely to fall quickly. To that end, both the U.S. and the international community need to have short-term and long-term plans. Short-term actions include announcing targeted sanctions on Islamic Republic leaders, appropriately reducing the Islamic Republic’s legitimacy in multilateral institutions like the UN, and increasing civic technology access; long-term actions include mobilizing needed humanitarian aid, emergency medical services, and greater international accountability mechanisms. One thing that we really haven’t been talking about—but we should—is that as Iranian protesters are being brutalized, there are lives, limbs, eyes, and more being needlessly lost due to a lack of medical care. I believe that international leaders (by “international leaders,” I mean every country in the world, as well as the United Nations, World Health Organization, Red Crescent, Doctors Without Borders, and the like) need to think harder and more innovatively about what aid and support they are providing to Iranian protesters. Getting emergency medical services into Iran will be a challenging task, but it is still an effort that should be made, preferably as noisily as possible. I would really like to see more people calling on the various humanitarian/health organizations to step up efforts to help Iranians who are fighting for freedom.  Shannon Melero is a Bronx-born writer on a mission to establish borough supremacy. She covers pop culture, religion, and sports as one of feminism's final frontiers.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Wednesdays and Saturdays.

|

![]()