There's no vaccine for stupid

|

No images? Click here  March 4, 2022 I am first a fraud or a trick. Or perhaps a blend of the two. Hello pals. This riddle has been rattling in my brain for a solid two days since watching The Batman, starring reformed vampire Robert Pattinson. The movie was pretty good if you’re into darkness and brooding. Speaking of darkness, Jennifer Finney Boylan writes this week about the start of the most difficult time in recent memory—the start of the coronavirus pandemic, which unimaginably began two years ago on March 11. I still remember those early days when we thought it would last just few weeks; two pandemic puppies later, I’m still working in pajamas, and you may be too. Also in today’s letter, Julianne Escobedo Shepherd recommends some escapism for those of us who still need it. Thoughts on The Batman (when I say thoughts, I mean please give me the riddle answer), the end of the pandemic or anything else? Send us some Batmail at [email protected]. —Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON (IN UKRAINE)

WHAT ELSE IS GOING ON

AND:

TWO YEARS LATERThere’s No Vaccine for StupidThe world we’re returning to is not the one we leftBY JENNIFER FINNEY BOYLAN  NURSES AT THE VA HOSPITAL IN THE BRONX, NEW YORK DEMANDING BETTER PROTECTION AT THE START OF THE COVID 19 PANDEMIC (PHOTO BY SPENCER PLATT VIA GETTY IMAGES) It was going to be just like old times. I’d been preparing for a reunion of my best friends from high school, that weekend in March 2020. The four of us—members of the class of 1976—were going to gather at a shore house in Atlantic City. My hope was that all those old faces might make me feel young. Then I learned that, as of that Sunday night, there had been a total of 31 confirmed deaths from the virus in this country. Damn, I thought. I guess we need to make another plan. By Friday the 13th, my classes at Barnard had gone remote, and the reunion with the boys was canceled. I grabbed a ride with my daughter back to our home in Belgrade Lakes, Maine. And there, with a few exceptions, I would stay for the next twenty-two months. There was an election. There was an insurrection. There was an inauguration. I got two Moderna vaccines, and a Pfizer booster. There was Delta, and Omicron. Finally, in New York at least, the number of cases began to subside. Like so many others, I began, tentatively, nervously, to return to the world. This January, I found myself back on the Barnard campus, walking down the familiar corridor in my department known as the “English channel,” and trying my key, for the first time in almost two years, in the lock of my office door. As it swung open, I thought of the description of archeologist Howard Carter opening the burial chamber of King Tutankhamun—100 years ago this November. “At first, I could see nothing, the hot air escaping from the chamber causing the candle flame to flicker,” he later wrote, “but presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist.”  A MEMORIAL IN AUGUST OF 2020 FOR THOSE WHO HAD DIED FROM COVID-19 (PHOTO BY MICHAEL M. SANTIAGO VIA GETTY IMAGES) There they were: all the pieces of my life, right where I’d left them. There was a stack of books I’d borrowed about Zora Neale Hurston, Barnard’s first African-American graduate; I’d been planning on writing a column about her. There was a stack of graded papers I’d never returned to their authors. On one wall was a long to-do list of things I had to write, and the deadlines. There were details for the national book tour I was supposed to go on. That tour, of course, been cancelled, along with so many other things: my son’s in-person graduation from the University of Michigan, my daughter’s wedding. For a moment I found it hard to remember the person I once had been. I sat down at my desk, intending to get started with the semester’s business, but instead, I just sat there for a long moment, feeling the tears in my eyes. They were tears of sadness, of course, sadness for everything, and everyone, we’ve lost. But they were also tears of rage. This crisis ought to have been a time when we got to see how good people can be. And we did see that, in sacrifices big and small; health care workers, and grocery store employees, especially emerged as heroes. But so many others showed us their cruel and narcissistic sides instead: distrusting and hobbling government, when what we needed was good governance; mocking and questioning medicine, when what we needed was reliable science; and above all, singing the songs of conspiracy and selfishness at a time when what we needed above all was to be looking out for, and caring for, one another.

The vast majority of people dying from COVID now are unvaccinated. With over 900,000 Americans dead, rather than publicizing the efficacy of vaccines, a whole cohort of frauds and blowhards has instead advocated horse de-wormer. Another genius suggests drinking your own urine. In Florida, Oklahoma, Texas, and Utah, laws were put into effect preventing schools from mandating the masks that could hinder the spread of disease. Because freedom, I guess. I am hopeful that COVID will eventually subside into something like the seasonal flu—an endemic virus that, within reason, we will be able to control and endure. But how do we live with the knowledge that, at the moment of greatest crisis, so many of our fellow Americans opted for ignorance instead? In fits and starts, we are slowly returning to our lives. But we are forever changed by what we have been through, and by what was revealed about so many of the people with whom we share this country. What was revealed to you? Did you find new sources of resilience and hope? I found some of that, to be sure. But I fear the pandemic has shaken me forever—not because of the disease itself, but because of what it forced me to see. Omicron may be on the wane, but the virus of heartlessness and ignorance is thriving. It may yet end us all.  Jennifer Finney Boylan is the Anna Quindlen Writer in Residence and Professor of English at Barnard College. She is a Trustee of PEN America and a Contributing Opinion Writer for the New York Times.  THE METEOR RECOMMENDSWhy I’m Binging a Fantasy Show About DruidsBrittania's Trippy EscapismBY JULIANNE ESCOBEDO SHEPHERD  SOPHIE OKONEDO AS HEMPLE ON BRITANNIA (IMAGE VIA METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER STUDIOS/EPIX) Like a lot of people, the last two years of social distancing has turned me into a voracious television consumer. In the absence of seeing friends or going dancing, I just binged what seems like every show ever made and, thanks to glut and languishing, promptly forgot 95 percent of any given storyline. But one genre of TV has stuck with me: ancient historical fiction in which women are situated as the most powerful, interesting characters. This week, Netflix released its sequel series to the great Vikings, Vikings: Valhalla, which is currently in its top two most-watched shows, and includes great fictional portrayals of real-life heroines Freydís Eiríksdóttir and Queen Emma of Normandy. I binged it, as well as the Netflix show The Last Kingdom (also about Vikings), but my favorite of all these early historical dramas is Britannia on Epix, which is set in 43 AD and concerns the Romans trying to get over on the Celtic Druids, who have a lot of tattoos. Britannia also has a fantastical element, with the Druids getting looped up on psychedelic brews and talking to their gods about prophecies, all to a classic rock soundtrack. (Its theme songs include Donovan’s “Hurdy Gurdy Man” and “Season of the Witch.") But the plot mostly hinges on Cait (Eleanor Worthington Cox), a young Celtic girl who embarks on a mystical hero’s journey to discover she is the Chosen One, meant to protect the Druids from the murderous Romans and basically rescue all humanity from war along the way. Season three is airing now and I’m thrilled by it, particularly as it’s added the great Sophie Okonedo to the cast—she’s one of the best actors alive and is brilliant and terrifying as a powerful high priestess. Truly, I will proselytize to anyone about how much I love this show. I’ve been watching all the other stuff, too—ask me about 2020 when I saw approximately 236 episodes of Love Island in nine months—but the immersive and often funny tone of Britannia has hit my perfect escapist sweet spot. (Though, let’s be real: I am also just a sucker for a big budget and a tattoo.)  You can't spell friends without s-e-n-d! So be a pal and share this newsletter with all of your faves, we'd really appreciate it. FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Wednesdays and Saturdays.

|

![]()

Reinventing the girlboss

|

No images? Click here  March 2, 2022 Hi, and welcome to the day after the State of the Union. Last night, Biden was in prime presidential form, which is to say his face was beat to the gods. On the issues, well—aside from his support of Ukraine, which included a solemn and moving ovation for UN ambassador Oksana Markarova, for me, his big shining moment was when he spoke up to defend trans kids and their parents via the Equality Act (though, as the journalist Katelyn Burns pointed out, the Equality Act won’t be passed as long as the filibuster exists). Generally, I liked what Rep. Rashida Tlaib said in response to the speech: that Biden should use his executive powers to cancel student debt and reduce carbon emissions, and everyone needs to get back to enacting Build Back Better (which of course won’t *presses rewind* happen as long as the filibuster exists). Also, I learned that a lot of powerful people (including the President) still don’t know what Defund the Police actually means. But more on that in the news below, along with Shannon Melero’s look at the current TV trend—via Inventing Anna and Hulu’s upcoming Elizabeth Holmes show—of pinkwashing female white-collar criminals with a girlboss sheen. Hope that you and yours are well and safe. —Julianne Escobedo Shepherd  WHAT'S GOING ON

AND:

—JES  CRIME TIMEThe Yas Queenification of White Women ScammersThere’s a reason we’re so fascinated with Anna SorokinBY SHANNON MELERO  JULIA GARNER AS ANNA DELVEY, JUDGING YOU FOR YOUR OUTFIT (IMAGE VIA NETFLIX) In 2018, when every New York glossy started covering the escapades of Anna Sorokin—a young woman who had defrauded her “friends” and several financial institutions (including City National Bank) by posing as a German heiress named Anna Delvey—I largely ignored it. The woes of New York’s elite monied classes simply weren’t of interest to me—that part of New York is so disconnected from what I know as a native New Yorker that it may as well be a fantasyland. If those over-educated Patagonia vest wearers got conned by some girl, that was their business. I saw no reason to engage with the Anna Delvey news cycle. Ultimately, the joke was on me: Recently, I spent an entire weekend glued to Netflix’s Inventing Anna, a fictionalized version of the New York magazine story that first broke the news of Sorokin’s crimes. After a solid two days of talking at my husband (he didn’t watch, so I had to reenact some scenes for clarity) about all the different angles the series covers, it occurred to me that the whole thing functions as a bit of a Rorschach test: Is the viewer looking at a criminal or just a misunderstood girlboss? If you haven’t seen the show or read the articles, think-pieces, and best-selling book about Anna Delvey, here’s the quick and dirty. Delvey got herself one step away from securing a $25 million loan from a bank to fund what she called the Anna Delvey Foundation, her concept for an exclusive social club for the mega-wealthy in New York. To create the illusion that she was a wealthy German heiress and hide the fact that she had no money and nowhere to live, Delvey (born in Russia) stayed in some of the most expensive hotels in New York City and skipped the bill at nearly every single one. She was arrested twice in 2017 for failure to make payment, and was ultimately found guilty of almost all of the charges brought against her, including first-degree attempted grand larceny, theft of services, and second-degree grand larceny—just to name a few. It is an incredible crime story that not even the writers’ room of Law and Order could have conceived, but what’s more fascinating is the story that came after the story: The heroic myth of Anna Delvey.  CONTRARY TO POPULAR BELIEF ANNA WAS NOT CHARGED FOR THE CRIMINAL ACT THAT IS THIS EYELINER/MATTED LASH COMBO (IMAGE VIA NETFLIX) Shaping the latest retelling of this myth is Inventing Anna creator Shonda Rhimes, who’s constructed a series that deals in a certain degree of subtle manipulation. One episode at a time, it chips away at the perspective that Sorokin is a scammer who got off easy (she served the minimum length of her sentence), giving her just enough girlboss and pseudo-feminist rhetoric to imply that maybe, just maybe, she was simply a savvy business person faking it till she made it. What Inventing Anna manages to portray so expertly is the iron grip that girlbossery had over the masses during the 2010s, when Anna began her climb to and subsequent fall from the top. She is a scammer; there's no two ways about it. But her scam worked thanks to one nefarious aspect of girlbossology: because she is a white woman who came from nothing and almost created a social club without a dime to her name, she enjoyed a unique benefit of the doubt from bankers, hotel managers, socialites and the public—which is played up in the series. And this is where Inventing Anna starts weaving in the girlboss narrative. TV Anna, played by Julia Garner, makes sweeping speeches about how women aren't taken seriously in business. Even as she sits in a prison cell, her reputation as an entrepreneur is more important to her than her freedom. One ancillary character describes the way Anna had to change her appearance—ditching the blonde for serious girl brunette, putting on glasses, wearing all-black power suits—to even be heard in the offices of some of the most powerful bankers and lawyers in New York, a strategy that somehow worked.

This is one of the subtle manipulations happening in the show: it’s so easy to relate to this moment. Who among us hasn’t tweaked her appearance to some degree to be perceived a certain way in the workplace? These moments of relatability between Anna and the audience work as perfect distractors from the fact that she also took large sums of money from non-rich, non-white acquaintances who were left to pick up the pieces. The show even goes so far as to subtly place blame on these individuals by making it seem like they deserved what happened to them because they had benefited from their friendship with Anna. Instead of focusing on the nature of the crime, the focus is on transactional relationships—before you know it, you’re thinking about that one friend who is always out but never pays for anything. It’s truly a masterclass in don’t look over here, look over there! Inventing Anna’s affinity for Sorokin is put to its biggest test during the incident between Anna and Rachel Deloache Williams—a writer and friend of Anna who was allegedly scammed out of a large sum of money and eventually cooperated with the police to apprehend her—which functions as a sort of line in the sand in the series. You’re either on Rachel’s side or Anna’s side; there’s no room for middle ground. Rachel believed she was defrauded out of more than $60,000 on a trip to Morocco. Anna (and her attorney) painted Rachel as a weak social climber who was just mad that she had to pay for a lavish vacation that she had planned. Now don’t get me wrong, in the Rachel episode, Anna’s behavior is deplorable and frightening. But as the series progresses, it tosses out tiny breadcrumbs in Anna’s defense and raises questions about Rachel’s responsibility in the Morocco ordeal. If Rachel could not afford her share of that suite, then why book it? Why did Rachel bring a work credit card on a personal vacation? What the fuck is up with that garden? Everyone is wrong, and no one is wrong. (Everyone is also a winner here: In real life, Williams turned a few pretty pennies for selling her story, and Anna Sorokin was found not guilty on that specific charge.)  KATIE LOWES AS RACHEL DELOACHE WILLIAMS (IMAGE VIA NETFLIX) The series also makes abundantly clear that Anna could only achieve what she did because she was white and able to move in certain circles without anyone giving her a second glance. Her achievements are entirely rooted in her whiteness and ability to position herself close to powerful white men. This is one aspect of the storytelling that the show gets right. But her portrayal as a girlboss—an unyielding byproduct of feminism as corporate branding—is far too generous for someone who carried out a staggering amount of white-collar crimes in such a short amount of time. It’s an unearned framing that only worked because she was able to fool so many men and for that aspect alone, the series awards her a proverbial Yas Queen trophy. It’s also a stark contrast to the way creators are compelled to cover “bad” men like Bernie Madoff or all of the investor bros from The Big Short. Where is the philosophical exploration of their manhood being the biggest motivating factor for their actions? On Thursday, March 3, another scorned girlboss will get the starlet treatment when Hulu releases its limited series on Elizabeth Holmes, The Dropout (there’s also a book and documentary about Holmes, if fiction doesn’t do it for you). It tells another story of another white woman who built another castle of sand, was praised as if she was the first woman in the history of women to accomplish anything, and watched it all come apart because she was selling her own pipe dream (and defrauding investors). I will absolutely watch it because I am a child of television, doomed to view whatever my overlords offer me. But underneath my own insatiable hunger for storytelling, I feel resistant to projects like The Dropout or Inventing Anna. It’s not that I’m against works that glorify crime—there are plenty of great movies about mobsters and murders (The Godfather is not one of them, come at me). Instead, it’s the implication that because these criminals are women, they are noteworthy in some way—or motivated by something greater, some higher calling from Lilith or Eve to commit crimes for the advancement of womankind. But sometimes, a crime is simply not that deep.  Shannon Melero is a Bronx-born writer on a mission to establish borough supremacy. She covers pop culture, religion, and sports as one of feminism's final frontiers.  READER QUESTION WEDNESDAY!Earlier this week, The Meteor held a briefing on the state of the caregiving crisis, which you can watch here. We’d love to hear from you on that issue. Tell us: Have you left your job in the past two years in order to care for a child or other family member? And if so, what would you have needed to be able to stay? Send your responses to [email protected], and we might feature your answer in next week’s newsletter.  We're new here and we'd appreciate it if you help us get by with a little help from your friends by sharing this newsletter with them. FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Wednesdays and Saturdays.

|

![]()

When your existence is illegal

|

No images? Click here  February 25, 2022 Hello Meteor readers—it perhaps goes without saying that it’s been a rough week in the world; as I write this, Russian troops have invaded Kyiv, and stories are pouring in about people fleeing Ukraine to Poland, having walked on foot for a full day. We’ve compiled a list of ways to help Ukrainians on our Instagram here. In today’s newsletter, we’ve got four transgender writers reflecting on how Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s hateful decree—and the transphobic legislation being passed across the country—affects their lives. After that, read Shannon Melero’s interview with Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman, editor of a new book called The Black Agenda: Bold Solutions for a Broken System, which elevates Black expertise in areas where it’s rarely sought. There is some good news, thank goodness. President Biden has nominated Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson to the Supreme Court; he kept his promise that he would nominate the first Black woman to SCOTUS, but what’s most exciting is that he’s nominated the most progressive judge among the candidates he was reportedly considering. (Lawyer and writer Dahlia Lithwick predicted her nomination in a recent edition of our newsletter.) More on that below. Hold the line, everybody. And drop us one, too: [email protected]. —Julianne Escobedo Shepherd  WHY IS IT ALWAYS TEXASOur Existence Is a Crime  TEXANS PROTESTING PROPOSED BANS OF TRANS ATHLETES IN TEXAS, 2021 (PHOTO TAMIR KALIFA VIA GETTY IMAGES) On Wednesday, Texas Governor Greg Abbott signed a decree that essentially criminalizes trans kids and their parents, demanding that the Department of Family and Protective Services investigate parents who support and affirm their kids' gender identity as child abuse. Abbott also ordered doctors and teachers—and deputized individual citizens—to report trans children receiving life-affirming care. This draconian, hateful step was the most recent measure in a right-wing war on trans people in multiple states, which includes 125 anti-trans bills currently on the table, according to the Human Rights Campaign. So what does the Texas news mean to the people most affected? The Meteor founding member Jennifer Finney Boylan asked four writers to answer that question here. Brynn Tannehill

|

|

You are receiving this email because you have subscribed to our newsletter. |

![]()

What does a Black agenda look like?

“The glaring omission of Black experts is so commonplace across Western society that it has become normalized,” writes Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman in the opening pages of The Black Agenda: Bold Solutions for a Broken System. A graduate student at the Harvard Kennedy School, Gifty Opoku-Agyeman, wants to raise her hand and ask one monumental question: “why public discourse about a global pandemic, which disproportionately impacted Black communities, was largely absent of Black perspectives.” The collection of essays she compiles explores the "convergence of at least three pandemics: Covid-19, racism, and state-sanctioned police violence," and how each of those things affects sectors like climate change, tech, and healthcare in Black communities. (In one expansive section about the climate crisis, Dr. Marshall Shepherd writes, "Ultimately, however, the weather-climate gap will not disappear until racial wealth inequality disappears.”)

So what does a Black agenda look like? Let's talk to the editor!

Shannon Melero: The Black Agenda kicks off by noting that historically, Black experts are only ever called upon for things specifically about the Black community—or when someone is trying to get their DEI initiative up and running. There was a slight shift in this during the summer of 2020, which you write about. Have you noticed any change in the academic or research community moving toward no longer pigeonholing Black experts two years into the pandemic?

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman: No. No. (Laughing) And it’s really because at the end of the day, as Doctor Tressie McMillan Cottom said recently, institutions can’t love you. Right? They’re things. And it’s no surprise. What I always tell people to keep in mind, with academic institutions, in particular, is that they were never built with Black and Brown people in mind. Harvard was founded in the 1600s. Where were Black people in the 1600s? So the way I really look at it is that, yes, institutions can’t love me. They won’t serve me. But that being said, I’m still going to push these institutions to at least see me, to hear me. Because at the end of the day, even if they aren’t hearing me, someone is listening, right?

One thing I noticed as a thread joining all of the essays was the argument for reparations. But what would you say is that one thing that brings all these experts’ concepts together?

Oh, reparations. I hadn’t even thought about it from that perspective, but you’re right, it does come up a lot. But I actually think the more salient or more obvious trend between the essays is criminal justice.

Just to be clear, nobody talked to each other before writing their essay. But as you see, criminal justice comes up again and again and again. Because at the end of the day, that is the root of a lot of the problems. If you already don’t see Black life as life, we have a problem. We can’t talk about voting rights. We can’t talk about health care reparations; we can’t talk about diversity in the workforce; we can’t talk about the future of work in the U.S. if you don’t think Black people are people.

And so the way that manifests is criminalizing Black people for existing. I can’t just be Black and exist because that is illegal. As I talk about this, I’m just thinking about what happened with Kim Potter recently. She basically got a slap on the wrist and the judge cried!

The statistic that shook me, and it still shocks me, is that out of 17,500 police killings between 2005 and 2021, only 140 officers were indicted in murder or manslaughter charges. That’s less than one percent! That’s actually 0.8 percent, to be precise. And the question becomes, well, when it’s fundamentally criminal to be Black in America, how does that spill over into every other sector of society? It’s illegal to be Black in America, and for some reason, that’s not top of mind for everybody.

So I guess the next logical question is, what’s the plan? It feels like this has been an ongoing battle for hundreds of years. How can we change this perspective, and is it even something that’s going to be accomplished in our lifetime?

I think it can. And I think it will be led by young people, I think we are going to be the ones to push against this idea in a very real way. That’s why you’re seeing such a visceral reaction. There are a lot of people who are trying to get rid of Black voting rights—I mean, it’s a coordinated effort that is giving Battleship precision, right?

There are entire generations of people who are sick of it. You’re seeing this [anger] in millennials, Gen Z, Gen X, and all of the people coming up after them. This is why you have this entire fight around what’s going to be taught in schools, however, because people [in power] understand that once young people find the truth, it changes everything. We saw that with Gen Z.

And what does implementing that level of change look like according to The Black Agenda?

It looks like putting Black people at the helm of conversation and having them lead the way. And that’s not at the expense of any other group. I think a lot of times people argue that if you’re centering one group of people, it means you don’t like anybody else. But who said that? What we’re saying is, what groups have it worse off? The group that is worse off should probably be leading the conversation around solutions because if a solution works for them, it’ll probably work for everyone else.

I can't just be Black and exist because that is illegal.

Now when we talk about agenda items in the book, what we’re saying is that with the way that things are going, Black lives have to be fully realized first and foremost. The fact that Black lives do matter is not something that should be up for debate, but right now it is up for debate. It doesn’t make any sense to me. Like, what do you mean? This isn’t debatable. The Black Agenda basically feeds off of the idea that if we know that Black life matters, we can address how the climate crisis is affecting Black lives, we can address health inequities, we can address how climate crises are affecting Black lives.

But you have to agree that Black life matters first. If you can’t agree with that fact then all of the other solutions proposed in the book are moot. The first step is you agreeing that Black people are people.

Shannon Melero is a Bronx-born writer on a mission to establish borough supremacy. She covers pop culture, religion, and sports as one of feminism's final frontiers.

How equal-pay victories really happen

|

No images? Click here  February 23, 2022 Hi, and welcome to our Wednesday edition. I’m still reeling from yesterday’s New York Times crossword (IT WAS A REBUS! BASED ON 2/22/22! Come ON) and freaked out by the fact that it’s 61 degrees in Brooklyn today. Empirically, I feel confident in saying that we are having a climate crisis. In today’s newsletter, we’ve got Shannon Melero fulfilling one of her life’s goals: writing about (and celebrating!) the U.S. Women’s National Soccer Team settling their long-running equal pay suit against U.S. Soccer. Believe her when she says she’s been following this case closely for six years like Nancy Drew with a magnifying glass. She’s cautiously optimistic, but also asks the important questions, like: when are all the other women’s sports teams going to get paid equally, too? But first, the news! And if you’d like to email us about what’s on your mind, or just tell us what you’re up to today, we’d love to hear from you: [email protected] —Julianne Escobedo Shepherd  WHAT'S GOING ON

AND:

—JES  THE BEAUTIFUL GAMEThe History of the U.S. Women’s National Team’s Fight for Equal PayI hope these women are drinking champagne out of a trophy this weekBY SHANNON MELERO  AN ASSEMBLY OF WINNERS (PHOTO BY BRUCE BENNETT VIA GETTY IMAGES) I cried when the United States Women’s National Team (USWNT) won their fourth World Cup in 2019. They were tears of excitement, tears of joy, and tears of immense pride at seeing these women—some of whom I’d watched play on a college field in Piscataway, New Jersey, because their league team didn’t have a stadium—be recognized by hundreds of millions. But they were also tears of anger. In the same year that the USWNT won that historic victory, they had, as a team, filed a gender discrimination lawsuit against the United States Soccer Federation (USSF) for unequal pay. Their claim argued that they were being paid less than the US Men’s National Team and were being given unequal resources—even though they had more World Cup wins than the men’s team, which to this day has won a total of *pulls out abacus* zero World Cups. On Tuesday, the USSF and USWNT finally reached a settlement in the lawsuit—to the tune of $24 million. This is an enormous achievement for the team. But as with everything that has to do with labor and money, it’s a little more complicated than that. For casual soccer fans, this case became news fodder on International Women’s Day 2019, when all 28 players on the USWNT filed that lawsuit. But this really all started in colonial America when the European settlers imposed their—just kidding! We don’t need to go back that far. (We could, but we won’t.) The struggle began in earnest in 1999 when the now-famous ’99ers won the Cup in a dramatic penalty kick-off against China. Don’t remember that match? I’ll bet you remember seeing a photo of Brandi Chastain, who scored the winning goal, kneeling on the grass, fists up in the air with nothing but her shorts and a sports bra. It’s the photo that launched a hundred sports bra campaigns.  THE ICON BRANDI CHASTAIN ON THE DAY SHE INVENTED THE CONCEPT OF ATHLEISURE AS FASHION (PHOTO BY RICH LIPSKI/THE WASHINGTON POST VIA GETTY IMAGES) But it also marked a more critical turning point: Over 90,000 people showed up to the stadium for that game, and 40 million tuned in to ABC to watch from home. Women’s soccer—which at this point didn’t have an American professional league—was finally in the spotlight. The ’99ers capitalized on the moment to expose just how poorly America’s champions were being treated. They went on strike, refusing to appear in a scheduled tournament in Australia, to protest not just the pay gap between themselves and the men’s team but the complete lack of maternity leave. In an interview with a few of the ’99ers, the Washington Post described the USSF’s stance as “treating[ing] pregnancy as a “career-ending injury,” where players like gold medalist Kate Markgraf weren’t offered contract renewals because they’d given birth. Thanks to public pressure, and the desire to ensure the top players showed up at the 2000 Olympics (where they won silver), the ’99ers were able to get maternity language introduced into USWNT contracts. (The policy wasn’t great, but at least women could no longer be cut from the team because they’d had a child.) After 2000, women’s soccer struggled to translate into a profitable American league, and the pay discrepancy issue was silenced by the fact that the men’s league, Major League Soccer, was thriving. Out of sight, out of mind. And the National Team itself had its own internal strife over differing views on LGBTQ representation. This changed in 2012 when the National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) was established, and talents like Ashlyn Harris, Christine Sinclair, Tobin Heath, and Alex Morgan brought back the excitement of soccer on a season to season basis. Then, in 2016, Hope Solo, Megan Rapinoe, Alex Morgan, Carli Lloyd, and Becky Sauerbrunn filed a wage discrimination action with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Their charge: Unequal pay and treatment between the men’s and women’s national teams, and even though the USWNT was doing superior work, the movement they began was called Equal Play, Equal Pay. (Just in case you forgot, the men’s team had not won a World Cup by this point, while the women’s team had three World Cup wins and four Olympic golds.) After that suit was filed, the team spent months carrying out their contractual obligations and negotiating a new contract behind the scenes—and according to a recent Instagram post from Hope Solo, the 2016 suit “still stands.” (It’s worth noting here that Solo does not see this settlement as a win, and is not entitled to the backpay included in the $22 million. She also does not believe the team will be able to successfully negotiate equal pay into their next contract.)

In 2017, the USWNT negotiated a new Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA) that addressed portions of the discrimination action. They were given increased per diems, better base salaries, and improved accommodation. It was a short-lived win. The women’s team had gotten a shred of parity, but it was in comparison to the old contract the men had. Once the men’s team got to the negotiation table with the USSF, there was another drastic change. The men were offered an entirely different (and lucrative) pay-per-play bonus structure which still saw them making more money per match than the women. As The Guardian calculated in 2019, the women’s team earned a $37,500 bonus (per player, with rookies expecting slightly less) for qualifying for a World Cup. On the other hand, top players on the men’s team would have been paid over $108,000 if they managed to qualify. The numbers become more staggering from there once you factor in brand sponsorships, appearance fees for post-match events, and base salaries. The women had to perform twice as well to get close to the income of a men’s team that couldn’t win their way out of a pie-eating contest against a toothless infant. (Not you, Tim Howard, you’re okay.) But now, six years, two medals, one documentary, and several hundred pages of legalese later—here we are.  ACCURATE SIGN IS ACCURATE. (PHOTO BY IRA L. BLACK VIA GETTY IMAGES) I cried when I saw the news Tuesday morning, not because I was joyful and overwhelmed. But because I was so shocked to read it that I literally dropped my phone on my face during my morning Twitter scroll. Like every fan and sportswriter who has followed this story through its nonsensical twists and turns, I am optimistic, but cautiously so. The 28 players who filed suit will have to agree on how to split $22 million in back pay, while an additional $2 million will be placed in a fund to support their post-career ambitions and charities (each player can apply for up to $500,000 from the fund). That money is contingent on the ratification of a new CBA, but that’s a necessary formality; they’ll get their cash. “Once a new CBA has been ratified, the district court will be able to schedule the final approval of this settlement,” The Athletic's Meg Linehan reported. But as any union member knows, the key to pay equity in the long term isn’t a one-time payout; it’s a solid contract that codifies equal pay as a basic standard, an outcome that Hope Solo does not believe is imminent. The plaintiffs in the 2019 case have said on numerous occasions that the fight is about more than just the back pay. It’s about ensuring the women who come after them will never have to go through all of this to get paid what they deserve. On that score, things look promising–but I’m too much of a cynic to call it certain. The Federation is pledging that under the new contract (the current one expires in March), they’ll work with the Player’s Union to establish equal pay between the national teams, and there’s reason to believe they’ll hold true to this promise. Cindy Parlow Cone, the current USSF president, has already made enormous strides in good faith, most notably in December, when the USSF agreed to equal working conditions for the teams. So yes, let’s all celebrate and anticipate a fair contract. But tomorrow, when the confetti is cleared and the hangover lifts, there are still equity battles to fight in the NWSL where Trinity Rodman signed a four year $1 million contract making her the highest-paid player in the league—which is $13 million less than what the 2021 MLS rookie of the year was given just to switch teams. Let’s also not forget the many fights still ahead at the WNBA, a league that has some of the best, most interesting athletes ever to touch a basketball but still gets asked to prove they deserve the financial and media investments the NBA takes for granted. There is still so much to do in the landscape of women’s sports, but what the US Women’s National Team has shown everyone is that it’s possible. It’s not easy, fast, or simple, but it can be done. So to borrow a line from Megan Rapinoe: “Let’s fucking go.”  Shannon Melero is a Bronx-born writer on a mission to establish borough supremacy. She covers pop culture, religion, and sports as one of feminism's final frontiers.  BEFORE YOU GODo you ever wonder why the US doesn’t provide paid parental leave when some of our global neighbors have already proven it’s possible? Why does it feel like there is a news item about child-care nightmares with parents and teachers clamoring for help every other week? Do you wish someone could give you concrete steps to address these issues without going absolutely nuts? If you answered yes to any of these questions, then you’re a) human, and b) officially invited to join us Monday night for a special briefing. With America’s care economy in crisis, it’s time to talk about what’s next in the movement for child care, family leave, and sustainable wages for care providers. Join us on February 28 to find out more. We’ll be joined by SuperMajority Executive Director Amanda Brown Lierman, Caring Across Generations chief of advocacy and campaigns Nicole Jorwic, Marshall Plan for Moms founder Reshma Saujani, and activist, writer, and filmmaker Paola Mendoza.  Thank you for being a friend. We'd love it if you threw a party and invited everyone you knew to read this newsletter. FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Wednesdays and Saturdays.

|

![]()

What book bans are doing to kids

|

No images? Click here  February 19, 2022 Cheers to the BookTokers, book worms, book lovers, and even actual books–this newsletter is for you. The subject of book banning is everywhere right now—but for school librarians, it’s more than just a talking point. So in today’s issue, Julianne Escobedo Shepherd spoke to the president of the American Association of School Librarians, Jennisen Lucas, about what it’s like to be on the front lines of this “life-or-death” issue. We’ve also got Suzan Skaar, a rad librarian from Wyoming, with a personal account of what happened after members of the organization Moms for Liberty challenged books in her Cheyenne school district. “The whole country is divided,” she says, “and Wyoming is no exception.” Before we dive into all that, a small favor. We’re new here, and we’d love it if you sent this email to a friend, or three! Or pop it in the group chat. Consider it your good deed of the day. Call us, beep us, if you wanna reach us at [email protected]. —Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON

AND:

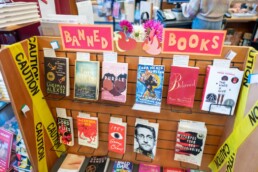

—SM  LIBRARIANS AT WORKWhat Are Book Bans Doing to Kids?“It leads to ‘I’m all alone’ kind of thinking”BY JULIANNE ESCOBEDO SHEPHERD  SOME CLASSIC READS ARE BEING CHALLENGED BY MOMS FOR LIBERTY, A GROUP BENT ON LIMITING THE LIBERTIES OF KIDS WHO JUST WANT TO READ. (PHOTO VIA GETTY IMAGES) The image above depicts just a few of the books that have been banned or challenged over the last few years, though today, some are considered cornerstones of American literature. And now in 2022, the censors are back at it, with legislators, school officials, and parents across the country engaged in a new, frenzied effort to ban certain book titles from school libraries. These ban attempts often cite “pornographic material” as their concern, but in reality, work to suppress certain points of view: The book Gender Queer, for instance, an illustrated memoir by nonbinary author Maia Kobabe, has been especially targeted in the last year, as have books like Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give, which deals with police brutality, and George M. Johnson’s All Boys Aren’t Blue, about growing up queer and Black. And last month, a Tennessee school board banned Art Spiegelman’s Maus, a canonical graphic novel about the Holocaust, citing cursing and the apparently objectionable nudity of cartoon mice. Many of these challenges have been spearheaded by members of Moms for Liberty, a conservative organization championing “parental rights.” (There is, hearteningly, a counterinsurgency of suburban moms called Book Ban Busters.) And while bans have been most successful in conservative states like Florida and Texas, books have also been challenged in nearly every state in the country, turning typically sleepy school board meetings into hotbeds of right-wing grievance. I spoke with Jennisen Lucas, president of the American Association of School Librarians, an organization on the front lines. Book bans and challenges are happening across the country. What are your broad, bird’s-eye-view thoughts about what’s been going on? Jennisen Lucas: This is, to me, extremely concerning [because] it’s so widespread and so large. At the American Library Association (ALA) and the Association of School Librarians, we’re trying to figure out, “How do we work with this at this huge large scale?” We definitely stand against censorship; we stand for intellectual freedom and the idea that students have the right to decide what they’re reading. [But conservatives] have branded ALA as being a very liberal organization and not somebody that you want to listen to. So how do we motivate people to say that there are definitely a lot of people out there who don’t think that we should be banning books? We tend to go with the idea that parents should be talking to their children about what they’re reading and not whole-scale trying to remove things from them. And then the fact that [the bans are] very specifically targeted: they’re targeting LGBTQ, they are targeting race. So it’s a challenge to erase those voices. And that’s not something that is really good for our constitutional republic. Most of this seems to come from Moms for Liberty, which consists of parents and seems extremely well-funded. It’s definitely a very well-funded and well-organized movement. But they are approaching this as, let’s get people riled up so that they go and talk to their school boards themselves. [The ALA says], Well, you do have rights for your kid, and when a parent comes to a librarian and says, “Hey, I’m concerned that my child should not be reading this,” we back the parent up. That’s their prerogative as a parent. The issue gets much bigger when it’s like, “No. I need that removed because I don’t think any kids should have access to that.” And we’re also being hit with a lot of varying definitions because people are coming in with, “Oh, that’s pornographic.” For most of them, this is normal teenage activity and has been for generations.

When you think about the books that have been banned—books like Gender Queer or The Hate U Give—it seems like they’re not just targeting whatever they think might be salacious material. They’re targeting specific identities in children. What we’re seeing as a national trend is a conflation between “pornography” and LGBTQIA+. Even if there is not any sex at all in the book, [book banners are] still claiming pornography because that’s not what they approve of as a society. Part of [our] concern is that the conversation itself is harmful to our students that identify in any of those categories; that when they’re hearing people say, “Hey, this is pornographic, and this is not acceptable, and this is just disgusting”—and these are some of the words that are coming from parents—that is not good for the mental health of our students. Each of our students needs to be able to see themselves in books and have that representation. It’s extremely important, and personally, to me, this is a life-or-death situation for some of our kids. If they are completely turned off from and denied access to materials like that, it leads to “I’m all alone” kind of thinking, which is a precursor to severe depression and suicidal thoughts. I wanted to ask you about that—I feel like we’re having this national conversation about politics, but the actual students and how they feel are getting lost. I have talked to my students about this, and it’s interesting to watch them get heated up about it. Especially our high school kids, who are preparing for adulthood and are in that situation where today I’m 17 and a minor and tomorrow’s my birthday. You’re at that cusp of legally being able to do all of this stuff on your own. They almost feel micromanaged. But the number of students around the country who are forming banned book clubs who are standing up and speaking at school board meetings—it’s all [types of students, even if they don’t identify as LGBTQ or BIPOC]. Books with LGBTQ content, books talking about race, and the history of race are for all kids. Everybody needs to be able to see that perspective.  Julianne Escobedo Shepherd is a Wyoming-born Xicana journalist and editor who lives in New York. She is currently at work on a book for Penguin about her upbringing and the mythology of the American West.  CHEYENNE, WYOMINGReport from a Red State LibrarianA CONVERSATION WITH SUZAN SKAAR, BY JULIANNE ESCOBEDO SHEPHERD  LET THE TEENS READ! (PHOTO BY JOHN KEEBLE VIA GETTY IMAGES) So how does it feel to be a librarian in one of the schools Jennisen Lucas describes? Suzan Skaar, a librarian at South High School in Cheyenne, Wyoming, knows. Last December, books by two authors—Tiffany D. Jackson and Ellen Hopkins—were challenged in Cheyenne by local members of Moms for Liberty. Though the upset seems to have died down now, it alarmed members of the school district, including teachers and librarians. Skaar talked to us about what it was like to be a school librarian at the center of one of these challenges. The whole country is divided, and Wyoming is no exception. Right now, there are seven certified secondary librarians in Cheyenne—we’re a pretty tight group. [Before the local book challenges], we worked with our new superintendent, and we prepared some information to put on the district homepage about book selection and how you can challenge books, that kind of thing. We’re lucky enough to have a really good board policy around selection and collection development. So we kind of met it head-on, in a very subtle way. What they were specifically challenging was Ellen Hopkins; she writes about issues kids are influenced by or have to deal with in their lives. [Hopkins’ YA novel Traffick focuses on the lives of five teens who escaped sex trafficking.] And, and so for some reason, they picked on her—well, she’s always picked on, she’s probably one of the most likely authors to be challenged. Then they picked up on Tiffany D. Jackson, and I spent Christmas break reading all of her novels. She’s a Black American author who writes about social issues that are really close to more urban-area Black teens, but they’re things that my kids identify with. [They’re so popular that] I can’t keep them on the shelf; I had to actually go read the books from the state app because all of my books were checked out over Christmas.

[After the initial objections at the December board meeting], our superintendent asked us, “So how many of you have had a request for the form to start a challenge process?” And not one of us had received an official challenge from the community. That just makes you wonder: it’s a national trend, but is it just a lot of yelling, or is it really a concern? I don’t believe that in a democracy, this should even be an issue. In Wyoming, we’re a little bit of “live and let live,” you know. “My kids are gonna read what I want them to read, but you can’t influence what my kids read—we all get to do that for ourselves.” I want to tell you something that happened this morning. We had a pep assembly, and we had a bunch of kids that didn’t want to go, so I let them come in here. And one little girl was looking around, and I said, “Can I help you find something?” and she said she wanted to look for a specific mental health disorder. So we went to the catalog, and I showed her how to look for it… and took her to the section. And her eyes strayed from the Mental Health section and went straight to LGBTQ Nonfiction. She said, “Oh my god, do you have this book? Can you have this book in this state?” And I said, “Well, so far, we do. I purchased [it] for our students because there’s a high interest in that topic and a lot of questions.” And she grabbed it—I don’t know if you’ve heard of the book, This Book Is Gay—and she goes, “Forget about the mental health. I’m checking out this one.” I have trust and hope in the generation coming up. They’re more savvy about how to deal with all the information that’s thrown at them.  WE'VE GOT A QUESTION FOR YOUDid you read in school? Of course you did! What's a book you remember reading that might be banned now and what did you get out of reading it? Tell us at [email protected], and we'll feature a few of your responses in a future newsletter. FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Wednesdays and Saturdays.

|

![]()

"I didn't want to be curated into whiteness"

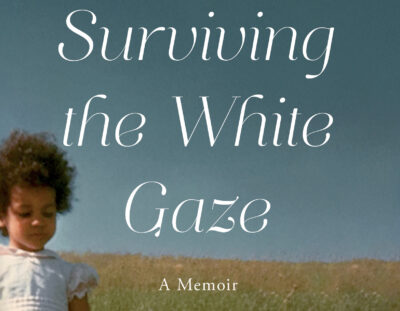

One year after Rebecca Carroll's memoir, the white gaze lingers

A year ago, I published the work I am more proud of than anything I’ve ever written—Surviving the White Gaze, my memoir about growing up as a Black child adopted into a white family, and raised in an all white, rural New Hampshire town. Every memoir writer knows that mining the truth can be a fraught and risky endeavor, and I certainly anticipated some fallout, hurt feelings, differences in remembrance. I could not have imagined, though, how keenly the response from my family would reflect not merely the truth in the book’s pages, but also the truth of America.

My mom called it a gift, until my dad called it an injustice, and then she agreed with him that they should consider hiring a lawyer to sue me. Their accusation: defamation of character. Their issues were not with me writing about the racism I endured during my youth, which went almost entirely unacknowledged within my family, but rather, with how I wrote about them; their unconventional marriage, my father’s ego. (He was upset that I’d included the fact that earlier in my life, I had misguidedly suggested there had been some blurred lines between us; I was wrong and said so in the book, but he still felt it was damaging to his reputation.)

I had invited my dad to read the book when it was still in manuscript form, when changes could still be made, but he had declined, which I can’t deny hurt my feelings deeply. We were very close when I was growing up—made countless mixtapes for each other, stayed up watching Late Night with David Letterman together, and shared a love for gallows humor, Swiss-German expressionist artist Paul Klee, the swoony crooning of Bryan Ferry and Roxy Music, romance languages, and romance in general. I absolutely worshiped him.

I had invited my dad to read the book when it was still in manuscript form, when changes could still be made, but he had declined, which I can’t deny hurt my feelings deeply. We were very close when I was growing up—made countless mixtapes for each other, stayed up watching Late Night with David Letterman together, and shared a love for gallows humor, Swiss-German expressionist artist Paul Klee, the swoony crooning of Bryan Ferry and Roxy Music, romance languages, and romance in general. I absolutely worshiped him.

When I left for college, we maintained a fiercely dedicated written correspondence, dad’s letters characteristically endless in page count, handwritten in his tiny, exquisite penmanship, detailing his findings in the local swamps and wetlands, his sanctuary, where he still spends hours finding and tracking painted and spotted turtles. But as I got older and grew more into myself as a Black woman, the more it became clear that I no longer fit within the narrative he had created for our relationship, and more broadly speaking, for our entire family.

Like many white male artists with outsized egos, my dad affected a microcosm wherein he, the infallible genius and hopeless romantic, existed at its center, buoyed by the near constant presence and adoration of women. It was a racially segregated space, into which I had been placed through careful, well-intentioned curation. But I didn’t want to be curated into whiteness, idyllic as it may have seemed to my parents and siblings. I wanted to be Black among Blackness. How was this never made available to me? I stopped worshiping and started questioning. And then I started to get angry. Why hadn’t my father tried to connect me with my community?

And, of course, it wasn’t just my dad. My mom sewed me a Black doll and found me a Black dance teacher. But still—my dance teacher was the first Black person I had ever seen in real life. I was six years old. I didn’t go to a Black hair salon until I was 12 years old. My first real Black friend wasn’t until college. My book grappled with those realities—it expressed my love for my parents, but also my anger. It expressed my reality, as lived and experienced by me. And they were outraged.

Twitter was making it clear: White parents get to decide how a family is made

It’s an outrage I’ve come to know too well. In December 2021, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments from state attorneys seeking to uphold Mississippi’s 15-week abortion ban. In her remarks, Justice Amy Coney Barrett, herself the white mother of two Black adopted children from Haiti, suggested that abortion isn’t really even necessary when adoption is right there. I found her remarks hideously cavalier, a callous trivialization of the complexities surrounding adoption, particularly transracial adoption, and the responsibility white parents take when they adopt Black children. I launched a thread on Twitter (as one does) saying so. The thread outlined the ways in which I believe transracial adoption can be seen as representative of the foundational dynamic between Black people and white people in America, which is inherently traumatic. It was retweeted thousands of times, but the backlash was swift.

My comments were full of endless fury. One (based on her avi) white woman tweeted: “TRAUMA???? What would the trauma had been if you were still with your birth mother? How the fuck UNGRATEFUL can one person be. Disgusting.” A white guy whose Twitter bio includes “just a dude” wrote: “So the argument is... it's better for black children to be aborted than adopted by white people? I'm not sure a lot of black children would agree, but, I'm no expert.”

Perhaps the most egregious responses came from right-wing commentator Dinesh D’Souza, who tweeted: “If it’s ‘enduring trauma’ for you to be adopted by a white family, you might consider that 1. The black patents [sic] that gave birth to you didn’t want you 2. There were evidently no black couples that chose to adopt you. Aren’t you grateful someone did?”

Twitter was making it clear: White parents get to decide how a family is made. It’s the very essence of America, where white parents, both figurative (the forefathers) and literal (adoptive parents), have set the standard of everything. And if you are a Black child who is lucky enough to be part of that construct—taken in either from foster care or, in my case, by a handshake agreement between your parents and the white teenage girl who was pregnant with you—well, you had better feel grateful.

Imagine presenting what you consider to be your career-best work, an impassioned plea to be seen, only to have your parents condemn it because of bruised egos.

Now try to think of one moment throughout history when this same dynamic hasn’t played out similarly, if not exactly, between Black and white America.

My parents did not sue me—there were no grounds—but ironically, their threat made me feel more Black than I’d ever felt before. It felt like a reminder that in America, if you are white, you can arbitrarily decide what constitutes an injustice, while threatening to bring law and order down upon anyone who says otherwise—in this case, a Black woman who wrote her story into existence.

If not for the support of the family I made and chose, generous reviews, and the overwhelmingly positive response from readers—of all different backgrounds, but in particular Black and biracial transracial adoptees, and other transracial adoptees of color—I might have thought it was all for naught. But they wrote me, in droves.

“I feel a little taller, less broken, less angry and grateful to be in this black skin,” wrote one of the adoptee DMs and emails I received. “Thank you for this book...from the whole entireness of my heart. I have to go cry now.”

Hard same.

Still Surviving the White Gaze

|

No images? Click here  February 16, 2022 Hello and happy Give Zendaya an Emmy week! In today’s newsletter, a very personal take on race, adoption, and what it means to be let down by those you love. Rebecca Carroll contemplates the year she’s had since first publishing her memoir, Surviving the White Gaze, including the ways her parents reacted to it. If you know any of Rebecca’s work, I don’t need to tell you how moving this essay is; it feels like receiving a gift to be let so intimately into her world. And if you’d like to hear more from Rebecca after reading, she’ll be in conversation with the author Ijeoma Oluo (So You Want to Talk About Race) on Twitter Spaces today, February 16, at 6 p.m. EST. Join them here. But first, the news. And as always, if you have questions, comments, or want to tell us how we’re doing, hit us up at [email protected]. —Julianne Escobedo Shepherd  WHAT'S GOING ON

AND:

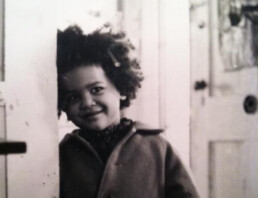

—JES  ON RACE AND FAMILYStill Surviving the White GazeWhat happened after my memoirBY REBECCA CARROLL  REBECCA CARROLL AND HER FATHER, 1974. (PHOTO COURTESY OF REBECCA CARROLL) A year ago, I published the work I am more proud of than anything I’ve ever written—Surviving the White Gaze, my memoir about growing up as a Black child adopted into a white family, and raised in an all-white, rural New Hampshire town. Every memoir writer knows that mining the truth can be a fraught and risky endeavor, and I certainly anticipated some fallout, hurt feelings, differences in remembrance. I could not have imagined, though, how keenly the response from my family would reflect not merely the truth in the book’s pages, but also the truth of America. My mom called it a gift, until my dad called it an injustice, and then she agreed with him that they should consider hiring a lawyer to sue me. Their accusation: defamation of character. Their issues were not with me writing about the racism I endured during my youth, which went almost entirely unacknowledged within my family, but rather, with how I wrote about them; their unconventional marriage, my father’s ego. (He was upset that I’d included the fact that earlier in my life, I had misguidedly suggested there had been some blurred lines between us; I was wrong and said so in the book, but he still felt it was damaging to his reputation.) I had invited my dad to read the book when it was still in manuscript form, when changes could still be made, but he had declined, which I can’t deny hurt my feelings deeply. We were very close when I was growing up—made countless mixtapes for each other, stayed up watching Late Night with David Letterman together, and shared a love for gallows humor, Swiss-German expressionist artist Paul Klee, the swoony crooning of Bryan Ferry and Roxy Music, romance languages, and romance in general. I absolutely worshiped him.  REBECCA CARROLL, 1973. (PHOTO COURTESY OF REBECCA CARROLL) When I left for college, we maintained a fiercely dedicated written correspondence, dad’s letters characteristically endless in page count, handwritten in his tiny, exquisite penmanship, detailing his findings in the local swamps and wetlands, his sanctuary, where he still spends hours finding and tracking painted and spotted turtles. But as I got older and grew more into myself as a Black woman, the more it became clear that I no longer fit within the narrative he had created for our relationship, and more broadly speaking, for our entire family. Like many white male artists with outsized egos, my dad created a microcosm with him, the infallible genius and hopeless romantic, at its center, buoyed by the near constant presence and adoration of women. It was a racially segregated space, into which I had been placed through careful, well-intentioned curation. But I didn’t want to be curated into whiteness, idyllic as it may have seemed to my parents and siblings. I wanted to be Black among Blackness. How was this never made available to me? I stopped worshiping and started questioning. And then I started to get angry. Why hadn’t my father tried to connect me with my community?

And, of course, it wasn’t just my dad. My mom sewed me a Black doll and found me a Black dance teacher. But still—my dance teacher was the first Black person I had ever seen in real life. I was six years old. I didn’t go to a Black hair salon until I was 12 years old. My first real Black friend wasn’t until college. My book grappled with those realities—it expressed my love for my parents, but also my anger. It expressed my reality, as lived and experienced by me. And they were outraged. It’s an outrage I’ve come to know too well. In December 2021, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments from state attorneys seeking to uphold Mississippi’s 15-week abortion ban. In her remarks, Justice Amy Coney Barrett, herself the white mother of two Black adopted children from Haiti, suggested that abortion isn’t really even necessary when adoption is right there. I found her remarks hideously cavalier, a callous trivialization of the complexities surrounding adoption, particularly transracial adoption, and the responsibility white parents take when they adopt Black children. I launched a thread on Twitter (as one does) saying so. The thread outlined the ways in which I believe transracial adoption can be seen as representative of the foundational dynamic between Black people and white people in America, which is inherently traumatic. It was retweeted thousands of times, but the backlash was swift.  THE AUTHOR AND HER CHILD. (PHOTO COURTESY OF REBECCA CARROLL) My comments were full of endless fury. One (based on her avi) white woman tweeted: “TRAUMA???? What would the trauma had been if you were still with your birth mother? How the fuck UNGRATEFUL can one person be. Disgusting.” A white guy whose Twitter bio includes “just a dude” wrote: “So the argument is... it’s better for black children to be aborted than adopted by white people? I’m not sure a lot of black children would agree, but, I’m no expert.” Perhaps the most egregious responses came from right-wing commentator Dinesh D’Souza, who tweeted: “If it’s ‘enduring trauma’ for you to be adopted by a white family, you might consider that 1. The black patents [sic] that gave birth to you didn’t want you 2. There were evidently no black couples that chose to adopt you. Aren’t you grateful someone did?” Twitter was making it clear: White parents get to decide how a family is made. It’s the very essence of America, where white parents, both figurative (the forefathers) and literal (adoptive parents), have set the standard of everything. And if you are a Black child who is lucky enough to be part of that construct—taken in either from foster care or, in my case, by a handshake agreement between your parents and the white teenage girl who was pregnant with you—well, you had better feel grateful. Imagine presenting what you consider to be your career-best work, an impassioned plea to be seen, only to have your parents condemn it because of bruised egos. Now try to think of one moment throughout history when this same dynamic hasn’t played out similarly, if not exactly, between Black and white America. My parents did not sue me—there were no grounds—but ironically, their threat made me feel more Black than I’d ever felt before. It felt like a reminder that in America, if you are white, you can arbitrarily decide what constitutes an injustice, while threatening to bring law and order down upon anyone who says otherwise—in this case, a Black woman who wrote her story into existence. If not for the support of the family I made and chose, generous reviews, and the overwhelmingly positive response from readers—of all different backgrounds, but in particular Black and biracial transracial adoptees, and other transracial adoptees of color—I might have thought it was all for naught. But they wrote me, in droves. “I feel a little taller, less broken, less angry and grateful to be in this black skin,” wrote one of the adoptee DMs and emails I received. “Thank you for this book...from the whole entireness of my heart. I have to go cry now.” Hard same.  ILLUSTRATION BY IRMGHARD GEHRENBECK Rebecca Carroll is a writer, cultural critic, and podcast creator/host. She is the author of several books, including her recent memoir, Surviving the White Gaze. Rebecca is Editor at Large for The Meteor.  BEFORE YOU GODon't forget to reserve the best seat on your couch for a Twitter Spaces conversation with Rebecca Carroll and Ijeoma Oluo happening today, February 16th, at 6 p.m. EST! We'll be waiting for you right here. FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Wednesdays and Saturdays.

|

![]()

The deadly act of telling the truth

|

No images? Click here  February 11, 2022 This week, it was reported that the Taliban is currently detaining at least nine foreigners in Afghanistan, including two UK journalists who were in Kabul to report for the UN. But we’ve long known about the Taliban’s hostilities toward journalists, especially women journalists—and of course toward women in general. That’s why today’s newsletter feels so urgent. First, Mariane Pearl sits down with the incredible Afghan women behind Rukhshana Media, a news organization that reports on women in Afghanistan and the Taliban government from the ground, at great personal risk. After that, Shannon Melero writes about France’s shameful new ban on hijab in sport and her own experiences as a hijabi athlete. In a week of headlines questioning whether foreign policy can truly be feminist, this edition will convince you that it’s more important than ever. As ever, if you’ve got thoughts—on what you’re reading, or what you’d like to read—we’re all ears: [email protected]. —Julianne Escobedo Shepherd  THE COST OF AN UNTOLD STORYSix Months of the TalibanWhat life is like for women in Afghanistan now—from two journalists fighting to get their stories out BY MARIANE PEARL  A WOMAN AND HER CHILD ON THE ROAD IN KABUL, JANUARY 2022. (PHOTO BY SCOTT PETERSON VIA GETTY IMAGES) Six months ago next Tuesday, Kabul fell to the Taliban, plunging Afghanistan’s citizens, but especially girls and women, into panic and despair. Rukhshana Media is one of the very few woman-run media outlets in the country; its two founders, Zahra Joya and Zahra Nader, now live in exile, working 18 hours a day to ensure coverage of the systematic oppression of women at the hands of the Taliban. I spoke with these extraordinary journalists in late January over Zoom. MP: Rukhshana Media, the news agency you created, is named after a victim of Taliban oppression. Can you tell us about her, and why you started the agency? Zahra Joya: For nine years, prior to creating Rukhshana, I sat in newsrooms, most often the only female to be seen, and saw how much women and girls’ lives were ignored by the media. We had no space, no opportunities to show our worth. Men genuinely believed we couldn’t do the job. So, I founded Rukhshana in 2020 with my own savings to tell our stories, drive change and foster a national dialogue about and with all women in Afghanistan, regardless of ethnicity or religious beliefs. Rukhshana herself was a 19-year-old girl from central Afghanistan who, in 2015, tried to flee an arranged marriage to be with the boy she loved. The Taliban accused her of adultery, dug a hole in the ground, leaving her upper body out, and stoned her to death. I chose her name so that each time we pronounce it we honor her—and fight against the risk of oblivion. Zahra Nader: My biggest fear is that young women who are taught history in the future will say, “I can’t believe there were once female journalists in our country.” There are only 100 female journalists left in Afghanistan (out of 700 before last August). You have reporters working inside Afghanistan and rely on volunteers. Can you explain how people bring stories to you? And are they in danger? ZN: They are not quite volunteers because we insist on paying our collaborators. Women have lost their jobs [since the Taliban took over], so this is also a way of encouraging them to join us and speak out. Some of the women now working with us are not journalists; they were students or teachers, so we train them on the job. ZJ: Right now, we have four female journalists and two men inside Afghanistan. We are looking for someone to cover the Eastern region, but the situation there is beyond control. Despite the danger, our reporters are doing remarkable work. In February alone, they wrote about two abducted women’s rights activists, the ban on women’s voices and music, and how former security forces fear being hunted down when applying for passports, among other critical reporting. We are constantly tracking our collaborators, making sure they are okay, but we don’t want them to take risks. Journalists themselves need to decide. No story is worth a human life, but the cost of an untold story is also very high. ZN: If we need to contact Taliban officials for comment, we do it exclusively from abroad. One time, I made such a call, and the next day, two women contacted me, pretending they needed help; these calls came from the Taliban trying to measure my vulnerabilities.

Afghanistan has one of the youngest populations on earth, with 63% of its people under the age of 25, meaning most Afghans don’t remember what life was like under the Taliban, which held power over roughly three-quarters of the country from 1996 to 2001. Do you have any memories of life under Taliban rule? ZJ: I was nine when the Taliban left. In order to go to school, I had been dressing up as a boy and called myself Mohammad. The ’90s were particularly harrowing for women. Now at least we have platforms, social media, and networks. They didn’t have any of that then. My mother told me there was no bread on the table. They didn’t even know that there were doctors and clinics that could save their lives. ZN: When the Taliban came the first time around, I moved to Iran, where I wasn’t allowed to go to school [because I was a refugee]. The concept of home became a very big deal. The day my parents told me we were going back was the best of my life. I went to school and held my head high. To me, school meant change—the Taliban were in history books, a mere nightmare from the past. We were a generation that was going to change this country for the best. Where were you last August, when the Taliban took Kabul? ZJ: That first day, I went to the office as usual, but my colleagues told me to leave immediately, so I went back home. The only thing I was able to grab was my diary. I was evacuated to London three days after the takeover. I lost everything. ZN: I was working on a story about women’s reactions to the Taliban. Suddenly on television, I saw one entering the presidential palace in Kabul. I knew they were coming, but that image brought it home. I didn’t think it would happen so fast. I sat there just crying. It wasn’t only the fall of a country I was witnessing; it was the death of the hopes of my generation. The Hazara community to which you both belong is being specifically persecuted by the Taliban. What do we know about Hazara women and what is happening to them? ZJ: We have always been discriminated against. Many Afghans believe that we don’t belong there as we are mostly Shia Muslims, and the majority [of Afghans are] from the Sunni sect of Islam. And if you are a Hazara woman, you are buried under several more layers of discrimination between your ethnicity and your gender. Yet, as journalists, we are very conscious about not letting labels and nationalism prevent us from representing all women.  RUKHSHANA CO-FOUNDER ZAHRA JOYA. (PHOTO COURTESY OF ZAHRA JOYA) The Taliban promised to respect women’s rights “according to Islam.” But “according to Islam” is a vague, and in this case threatening, formulation, as the interpretation of the Quran is complex and varies widely depending on the individual. ZN: In May 2021, I asked the Taliban to define what they considered women’s rights. Every Muslim country has its own interpretation of how women should live. Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Iran—they are all different. The Taliban never answered the question or defined anything. But they are slowly pursuing their agenda and imposing a very narrow interpretation of Islam. The word “misogyny” lacks the power to represent their ideology towards women. One of the first Taliban decrees stated that “women are human beings.” They actually had to wonder about that. How at-risk are the women who were most visible during the last 20 years? Journalists, of course, but also women working in the armed forces, as lawyers or activists? ZN: Rukhshana is doing everything we can to answer that question. We hear about so many stories of women being killed but often we can’t run them because we can’t reach anybody to confirm the facts. When we can talk to the family, friends or relatives, we reach out to the Taliban and they simply deny responsibility: They say these women have died because of family feuds. How is it possible that so many public, visible women are suddenly all dying from family feuds? It’s so easy for Talibans to find and execute these targeted women. All the public data, fingerprints, census and personal information are in their hands now.

In January 2022, a delegation of Taliban was hosted in Oslo to speak with world representatives. Officially, the meeting was to address the economic crisis, but activists see that meeting as a first step towards legitimizing the Taliban government. What do you think? ZN: When we challenge the fact that the Taliban should not be invited to the world table, we are told that Afghanistan has too many problems. That we should resolve the economic crisis first, then we can talk about women. But how do you resolve starvation if half of the country is under house arrest? I was saddened by the lack of protests from the Norwegian people, who ultimately paid for the expenses of that meeting. How can the international community help Afghan women? ZJ: The best way is to put pressure on your governments, to tell the world that you disagree with what is happening. Ultimately, this is about all women and the way we can be treated when men are at their worst. Show what you stand for, challenge inertia. Another way is to support Afghan women who are now outside the country. You can help them help us.  PHOTO BY JUAN LEMUS Mariane Pearl is an award-winning journalist and writer who works in English, French, and Spanish. She is the author of the books A Mighty Heart and In Search of Hope.  WHAT ELSE IS GOING ON

AND: