She Fled Fear—and Found It Here

A woman who escaped danger in Afghanistan reflects on what life is like under ICE.

By Lima Halima-Khalil

I drop my three-year-old daughter off at library classes every morning. The library is two minutes from our home in Ashburn, Virginia. Each time, the same thought crosses my mind: Do I have my ID on me? Will my driver’s license be enough if I am stopped?

It is highly unlikely that I will encounter ICE on a two-minute drive to the library. Ashburn isn’t exactly an ICE hub. And yet my fear is constant, embodied, and real. And by the way, I am an American citizen.

I grew up believing America was a mighty country, one so powerful that the rest of the world stood intimidated by its strength. When I first came to the United States in 2006 for an education program from Afghanistan, a country still at war, the vastness of this place revealed itself not only in its size, but in the generosity of the people I met. After that, America became a place I always returned to. I have been part of the American education system since 2010, returning several times for various degrees. I’ve witnessed multiple presidential elections and participated in the most recent one as an American citizen myself.

But after all these years, one lesson about my new home stands out above the rest: This country is led, shaped, and sustained by fear. Outside this country, nations tremble at the military and economic power of the United States, but inside it, people live as though danger is always lurking.

Fear raises money and sustains campaigns. Fear keeps people glued to screens and locked into cycles of outrage. Fear sells guns, justifies surveillance, expands borders and prisons. Much of this fear is not grounded in lived reality but manufactured and amplified by politicians who rely on it to govern. Fear spills into kitchens, sidewalks, classrooms, and moments meant to be ordinary and human.

One of the most brutal tools in this ecosystem right now is ICE. Raids, detentions, and aggressive enforcement practices operate not simply as immigration policy, but as a mechanism of fear, reminding entire communities that their sense of belonging is fragile and conditional. ICE does not need to be everywhere to be effective. The possibility of its presence is enough.

This pervasive fear turns ordinary routines into sites of anxiety. I remember hesitating before offering to share our Thanksgiving meal with our nosy white neighbor, suddenly gripped by thoughts I never imagined I would carry. What if he calls the police on us and claims I was trying to poison him? What if kindness itself is misread as a threat, or hospitality as danger?

Afghans discovered how quickly they could become the “other,” regardless of their sacrifices, their loyalty, and their love for this country.

I recognize these impulses, because fear is not new to me. I lost my school, my home, my loved ones, and eventually my country because I wanted freedom from fear. Millions of Afghans had believed in democracy when America promised it to us for 20 years, until the United States withdrew from Afghanistan in 2021. We voted, we hoped, we worked alongside our American partners for a shared dream, but that freedom never came. In 2020, when my 24-year-old sister was killed by the Taliban in an IED attack in her car, that truth became undeniable. I understood then that Afghanistan was no longer safe, and that realization is what led me to come to the United States permanently.

When the Taliban returned to power in 2021, many Afghans, including members of my own family, were evacuated and brought into this country by our American allies. They arrived in this country under extremely harsh circumstances, believing they would find dignity, safety, and a chance to contribute. Instead, they discovered how quickly they could become the “other,” regardless of their sacrifices, their loyalty, and their love for this country.

I was reminded of this again in November of last year, after a man from Afghanistan, who had been trained and worked for the CIA in his country, shot two National Guard members in Washington, D.C. Overnight, an entire community began to be seen, once again, as terrorists. Instead of a careful and humane conversation about mental health, trauma, or resettlement failures, the Trump administration halted all immigration from Afghanistan and pledged to re-examine green card holders from 19 countries. Afghans, many of whom fled the very forces America claims to oppose, were once again forced to prove their innocence.

This is how fear functions. It identifies a moment of tragedy, strips it of context, assigns collective guilt, and converts pain into political currency.

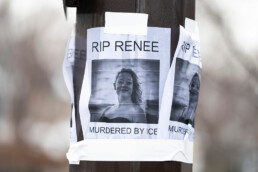

For a long time, I believed that fear in this country belonged primarily to people of color, that violence was uneven, predictable, and racialized. Then the killings of Renée Good and later Alex Pretti shattered that belief. They forced a painful realization that in today’s America, no one is safe, not five-year-old Liam Conejo Ramos, not women citizens like Dulce Consuelo Díaz Morales and Nasra Ahmed, not elderly citizens like Scott Thao or longtime residents like Harjit Kaur, not white Americans, either.

Lately, I have felt fear settle into my own body in a way I did not expect. I realized I had been going to sleep holding fear, living with the same quiet dread that so many people here carry without ever naming it. One night, I caught myself thinking, almost with disbelief: Congratulations, Lima, you are an American now.

But it does not have to be this way. Americans deserve more than this constant weight of dread, clinging to them like a second skin. We deserve a country where fear is not the engine that keeps the system running, where safety is not promised to some by threatening others, and where power is not sustained by keeping people afraid.

Lima Halima-Khalil, Ph.D., is the program director of the “I Stand With You” campaign at ArtLords, a collective she co-founded, where she mobilizes global awareness against gender apartheid in Afghanistan. Her research explores youth resilience amid violence and displacement. Her writing has appeared in Foreign Policy, TRT World, and academic publications.

Party Like It's 1946

January 29, 2026 Salutations, Meteor readers, I’m in my nerd-girl history bag today—let’s get to it! Ahead of a planned general strike tomorrow, we take a look at civic actions of yesteryear and what we can learn from them now. Plus, Rebecca Carroll on Broadway’s “Liberation.” On the picket line, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONShut it down: Tomorrow, activist groups, student associations, labor unions, businesses, and regular people across the country will be protesting ICE by staging a national shutdown via a general strike: “no school, no work, and no shopping.” Leftists and even some establishment Democrats have long yearned for a sweeping general strike, and the impact of Minneapolis’s version last week has made the prospect seem more possible. But many who’ve lost hope may be wondering: How can anyone pull this off? Do these things even work? You don’t have to look too far back to answer those questions. We saw the power of a general strike in Puerto Rico in 2019 when the people ousted a corrupt governor. In 2024, South Koreans held a general strike as a direct response to President Yoon Suk Yeol’s declaration of martial law. But the last time the U.S. mainland truly saw general strikes grind businesses to a screeching halt was in 1946. It was known as the greatest wave of strikes in American history, with over 4 million workers withholding labor in Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Texas, New Jersey, and California. The workers demanded better pay, safer working conditions, and an end to unfavorable union deals that came as a result of post-war economic policies. Entire industries were brought to their knees.  THE YEAR OF THE STRIKE, WHICH FIRST CAME TO LIFE AT THE END OF 1945, IMPACTED WORKERS ACROSS INDUSTRIES. IN NEW YORK, WORKERS WENT ON STRIKE IN JANUARY FOR FAIR WAGES FROM WESTERN UNION. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) The largest general strike that year happened in Oakland, California—and it was kicked off by a small group of determined women. During World War II, to replace men who had been enlisted, women took union jobs in shipyards and factories. But when the war ended in 1945, they had to give up those jobs for returning soldiers. Women who wanted or needed to continue working ended up in retail, where there were no unions and few labor protections. At Kahn’s Department store, workers were forced to endure a demoralizing “Ready Room,” where on-call workers would spend unpaid hours waiting for work that sometimes never came. In October of that year, women (and some men) retail workers organized a strike that was 400 strong. After violent face-offs with the police, the strike ballooned to more than 100,000 workers from various industries, effectively shutting down a major city for two days. The bars were allowed to stay open, on the condition that they put their juke boxes on the sidewalk to play for no charge; the hit song “Pistol Packin’ Mama, Lay That Pistol Down” filled the streets. “People who worked throughout the War had been taking all this crap from employers in the name of the war effort,” Stan Weir, who was an organizer for the United Auto Workers at the time and joined the strike in Oakland, recalled in a 1990 interview. It was “that kind of phony patriotism, instead of real patriotism.” (It’s a distinction worth revisiting in an era when some people define “patriotism” as weaponizing fear, white nationalism, and violence.) The government was so shaken by the events of 1946 that the following year, Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act, which severely limited unions’ abilities to authorize general strikes. Meanwhile, the Oakland women were beaten, mocked, and ignored. But they kept going, and in May 1947, after what probably felt like months of hopelessness, Retail Clerks Local 1265 was recognized. The general strike they inspired in their city changed the course of history. So, could a mass shutdown on Friday really change anything? The proof is in the past. AND:

What If We Centered Black Women in the Story of “Liberation”?A conversation with the women behind the Broadway playBY REBECCA CARROLL  CARROLL IN CONVERSATION WITH THE STARS OF "LIBERATION" AND GLORIA STEINEM. (COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR) Bess Wohl’s critically acclaimed play “Liberation” will take its final bow this Sunday. The Broadway show is a nuanced retelling of the feminist movement through the lens of an unnamed adult daughter seeking to understand her late mother, Lizzie, a journalist in 1970s Ohio. Lizzie (Susannah Flood plays both mother and daughter) is white, of course; stories from the feminist movement seem to almost always center white women. To Wohl’s credit, the play includes a few clear nods to the historical exclusion of Black women from the movement. There are two Black characters: Celeste (Kristolyn Lloyd), a book editor who is part of Lizzie’s consciousness-raising group, and Joanne (Kayla Davion), a working mother who is very much not part of the group. Still, these two Black women are pitted against each other in a key moment, wherein Joanne questions Celeste’s motivations for being part of the all-white women’s group. The scene concludes with Lizzie bringing it back to herself. I wanted to talk about it all, so, along with my colleagues at The Meteor and the extraordinary support of feminist icon Gloria Steinem, I moderated a talkback with Lloyd, Davion, Wohl, and much of the cast at Steinem’s home in Manhattan. On what feminism means to them: Davion: It’s about the confidence in my own skin…What does it mean to be alive? I can't talk about being alive without mentioning feminism. Wohl: I love what you just said, Kayla…as I’ve gotten older, I’ve started to wonder how big can the definition of feminism be without losing meaning. How expansive can we make it? On why it’s so hard for Black women and white women to do feminism together: Davion: I code switch. Like, every day. So that means that I can’t live in the fullness of myself. [It’s often said or implied that] I should be doing something else, that there’s a more professional way of doing things, that my hair should be a specific way. But what does that have to do with the things that I have to say as the person that I am? I feel like we haven’t come into the real understanding of acceptance, because there’s still this idea of what it looks like to be a modern-day woman. Lloyd: The system allows for women who are not Black to experience much more ease. When it actually comes to fighting the fight and getting uncomfortable, they don’t know how. On how the actors approached their roles: Davion (who plays a white woman, Lizzie’s mother, in one scene): I was terrified…As a Black woman, knowing that this audience is about to watch me transform into a white woman, the first thing I'm thinking of is ‘I don’t wanna be targeted.’ I don't want people to think, ‘Why is this Black girl doing this?’ And for Black people, I don’t want them to look at me and be like, ‘Now Kayla, why?’ Lloyd (who grew up in a predominantly white community): On occasion, it does feel like a re-traumatization…[I’ve] been in therapy for healing from having to be in all-white spaces, and then [I] have to be the only one in this all-white space on stage telling the story of this woman who I don't imagine in New York spends much time in all-white spaces. She’s also being re-traumatized being back in Ohio, where she has to be closeted [as a lesbian] and there's no other group for her to express herself in. So, I find that I am able to pull on old feelings, which is why my ritual for getting out of Celeste is very specific. At the end of every show, I have to shower the smell of Celeste off. Before we go into the show, I tell myself: ‘You’re not a race traitor. Some woman out there is gonna be liberated because she sees you.’ There is something you have to turn on as a Black woman, and kind of, like, lower down when you’re in that space…these women are not gonna be able to meet you where you’re at. They just don't know your experience. They don’t have your skin.  WEEKEND READING 📚On the needles: Resistance knitting is back. (Slate) On (not) all women: Dayna Tortorici digs into feminism’s 200-year-old history of infighting. (n+1) On human rights: The Taliban outlawed all forms of birth control in Afghanistan. Women are being “broken” by pregnancies and untreated miscarriages. (The Guardian)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Doctors and Nurses vs. ICE

January 27, 2026 Hey there, Meteor readers, The ice outside my door is so thick, I could probably skate on it if I really tried. But considering everything going on in the world, that’s not the worst thing to see in the morning.  WNBA STAR AND UNRIVALED CO-FOUNDER BREANNA STEWART. (SCREENSHOT VIA INSTAGRAM). In today’s newsletter, Dr. Heather Irobunda helps us understand what healthcare providers are feeling right now. Plus, the next general strike is coming. Throwing salt, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONFighting for our health: “There’s this thought that our scrubs—our professions—would protect us,” says Dr. Heather Irobunda, a New York-based OB/GYN and reproductive rights advocate. To see Alex Pretti “shot like that was very jarring for our field.” Pretti, an ICU nurse at a Veterans Affairs hospital in Minneapolis who was murdered by federal agents on Saturday, has sparked action across the country. His killing—much like the killings of Renee Good, Keith Porter, and Silverio Villegas Gonzelez—has reminded us that everyone is unsafe as long as ICE and CBP agents are allowed to operate unchecked. While activists have long been raising the alarms about ICE’s unmitigated cruelty, Pretti’s status as a nurse has added a new dimension to the conversation. The medical field has come out strongly against Alex Pretti’s killing, emphasizing nurses’ roles as guardians of the vulnerable. (The Washington State Nurses Association pointed out a germane directive in The Code of Ethics for Nurses: “Where there are human rights violations, nurses ought to and must stand up for those rights and demand accountability.”) It’s hard to continue defending agents once they’ve murdered a caretaker who, in his last act on earth, was trying to shield someone from pepper spray. Is that not the kind of person—the kind of man—we ask our children to work toward becoming?  PROTESTORS IN MINNEAPOLIS THIS WEEK (VIA GETTY IMAGES) For those in the medical field, ICE’s increased presence isn’t just a question of morality or policy; it’s a threat to public health. On one level, Dr. Irobunda says, the connection is extremely straightforward. “One of the biggest markers of health is mortality,” she says. “They are killing people in the streets.” And there’s a ripple effect. Dr. Irobunda shares that one of her patients, a pregnant woman with gestational diabetes, lost her husband to deportation. He was the primary breadwinner, and when he was arrested, she couldn’t afford food and was eating only rice and plantain for days at a time. More than likely, her child will have diabetes at birth. Patients are also skipping appointments—including, as reporting from The 19th highlights, crucial prenatal care—for fear of being arrested on their way to the doctor or hospital. In Dr. Irobunda’s neighborhood hospital in Queens, ICE agents “routinely hang out down the street,” she says. ICE isn’t just looking to arrest patients, but also doctors and nurses with visas or permanent residence, who are “scared to come to work, too.” She explains that due to a shortage of healthcare workers in the U.S., doctors have been traveling from other countries to treat patients. But issues with visa delays and concerns over ICE have made getting doctors into hospitals that much harder. Despite the dangers, the medical community has been incredibly vocal about the health implications of ICE’s scare tactics. Just last month, healthcare workers staged a protest outside an ICE facility in Portland, Oregon. Doctors have also accused ICE of medical neglect for people in detention—a plausible accusation considering that in both the Good and Pretti killings, ICE blocked medical personnel from the scene.  PROTESTORS IN OREGON "EXERCISING" THEIR FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHTS OUTSIDE OF AN ICE FACILITY. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) “A lot of us were taught that this is an apolitical job,” Dr. Irobunda says. “In an ideal society where everybody's treated equally and getting what they need, we wouldn't have to be political.” But in a system where policy can have the power to change health outcomes for millions, Dr. Irobunda says, “we have to be involved. No one’s safe unless we’re all safe.” AND:

THE SMILE OF A WINNER ON AND OFF THE FIELD (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

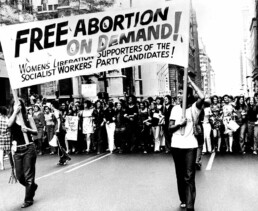

What activists knew when Roe was decided

January 22, 2026 Hi, lovely Meteor readers, Today is one of my closest friends’ birthdays, a balm upon a far more bittersweet milestone: the 53rd anniversary of the Supreme Court’s now-overturned decision in Roe v. Wade. At least there’s birthday cake.  Today, we hear from early pro-choice activists on what it felt like that day when Roe was decided (hint: it’s complicated). Plus, some historic Oscar nominations and your weekend entertainment. Stuffing my face, Nona Willis Aronowitz  WHAT'S GOING ONHope and fear: Fifty-three years ago today, the Supreme Court handed down the Roe v. Wade decision. In a 7 to 2 vote, the justices struck down state abortion bans, replacing them with detailed national guidelines based on weeks of pregnancy. Bending to the groundswell of the women’s movement, four states—Alaska, Hawaii, New York, and Washington—had already repealed their abortion bans, and 13 others had expanded exceptions. But Roe made the right to abortion, based on the constitutional right to privacy, protected everywhere. What was that moment like for women active in the movement? In a post-Roe world, it’s easy to imagine that it was a day of unequivocal joy. I was curious, so I sought out some women who remember it clearly—and discovered that the truth is far more complicated. Yes, there was relief. Heather Booth, who’d started an underground abortion service called The Jane Collective eight years before when she was a student at the University of Chicago, remembers thinking: “FINALLY!” After nearly a decade of abortion advocacy, “the fear, hardship and danger for women who wanted to end an unwanted pregnancy would be addressed.” Dr. Wendy Chavkin, who’d occasionally lent the Janes her Chicago apartment and had organized travel for women to get abortions in New York, recalls the period after Roe as “heady days.” She and her fellow student activists felt “hope, determination and a big vision that saw links between gender and racial discrimination.” Shortly after the decision, she became a counselor at the first legal clinic in Detroit and eventually went to medical school to become an abortion provider herself.  WE GOTTA BRING BACK “FREE ABORTION ON DEMAND.” CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES But many feminists were wary of the meticulous pregnancy timetable the Supreme Court had laid out. “I saw it as a serious compromise,” says Carol Giardina, an early member of the women’s liberation movement in Gainesville, Florida, who recalls referring girls in her freshman dorm to abortionists back in 1963. Although the decision did represent “a mighty win for organized feminism-people power,” she says, her cohort had been “fighting like tigers for repeal of any and all laws on abortion.” That demand, remembers Alix Kates Shulman, radical feminist and author of Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen, sprung out of the worry that “any law would contain restrictions on full reproductive freedom and be vulnerable to constant attack. Which is precisely what happened.” Several women referred me to abortion activist and Redstockings member Lucinda Cisler’s 1970 essay in the feminist journal Notes From the Second Year. States were beginning to introduce laws that legalized abortion, but with exceptions—which, Cisler warned, “can buy off most middle-class women and make them believe things have really changed, while it leaves poor women to suffer and keeps us all saddled with abortion laws for many more years to come.” The only option, she argued, was total abolition of laws restricting abortion. And then there were the women who had other things on their minds. “I’m sorry to say I shrugged at Roe,” says Loretta Ross, who went on to be cofounder of SisterSong and one of 12 architects of the theory of reproductive justice, which encompasses far more than the right to abortion. In 1973, Ross was a teenage mother suffering from acute pelvic inflammatory disease as a result of the infamous Dalkon Shield IUD; instead of removing her IUD, a white, male OB/GYN misdiagnosed her for months until her fallopian tubes ruptured and she was forced to undergo sterilization. She’d had a “perfectly safe legal abortion” several years before in Washington, D.C.; “it wasn’t my lived experience to be denied.” So “while other people were celebrating Roe,” she recalls, “I was having the classic experience of a Black woman whose white doctor was deciding she doesn’t need to have any more kids.”  LORETTA ROSS IN 2022. CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES Although she wouldn’t read it until years later, Ross cited a 1973 editorial by the National Council of Negro Women’s Dorothy Height, who sounded a cautionary note about Roe v. Wade and its potential to worsen state control over Black women’s bodies: “We must be ever vigilant that what appears on the surface to be a step forward, does not in fact become yet another fetter or method of enslavement.” Ross’s sterilization led her to file (and win) a lawsuit against Dalkon Shield manufacturer A.H. Robins, and devote her life to bodily autonomy in all forms. If we don't “intersect race, class and gender,” Ross says, we’ll “never understand the full impact of Roe.” In our new landscape, after Dobbs, many activists are starting to come around to the idea that restrictions and exceptions have no place in abortion care. (They’ve succeeded in getting pro-choice states like New York, whose law goes further than Roe, to agree.) These early activists remind us that perhaps our north star shouldn’t be restoring Roe, but to wrest our reproductive justice out of the hands of politicians—and into our own. AND:

RUTH E. CARTER IN AN EXTREMELY TACTILE PIECE OF CLOTH. CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES

WEEKEND READING, WATCHING, AND LISTENING 📖 👁️ 🔊On a complex heroine: On the occasion of the Roe anniversary, I rewatched “AKA Jane Roe,” a documentary on the case’s plaintiff, Norma McCorvey…and seriously, wow. (FX) On cop-hating: A close read of an uncollected Joan Didion essay asks the question: What made her consign the piece to obscurity? (Dispatches) On heteropessimism: I am embarrassingly late to Heated Rivalry but maybe you are too, and would enjoy Tracy Clark-Flory and Amanda Montei discussing the show as an escape from heterosexuality. (Dire Straights)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Chrissy Teigen on the “sisterhood” women deserve

January 21, 2026 Dear Meteor readers, We’re coming to you with a treat today—a story about reproductive healthcare that, for once, gives us hope. Tomorrow marks the 53rd anniversary of the Roe v. Wade decision. More than half a century later, in a country that no longer grants the freedom that that ruling declared, it’s easy to get mired in the onslaught of harrowing news about our bodies and our lives. But everywhere, there are warriors who keep doing the work of caring for pregnant people, and they are not mired. They are moving forward, every single day. TV personality and best-selling cookbook author Chrissy Teigen has herself helped to humanize reproductive healthcare. She has spoken about her own experience having a lifesaving late-term abortion; visited the Feminist Center for Reproductive Liberation, a clinic in Georgia, in 2024; and then discussed her experiences with Vice President Kamala Harris during the 2024 presidential campaign. “I started crying once I saw this beautiful mural of butterflies above the operating suite” at the Feminist Center, Teigen told Harris at the time. A doctor there “looked me in the eye and she said, ‘You could have had butterflies.’”  Then, in 2025, The Meteor traveled to Tennessee with Teigen on another visit—one that shows that everyone deserves butterflies, and that you can’t talk about abortion care without talking about maternal care. CHOICES Center for Reproductive Health, a Memphis-based clinic, provides the full spectrum of care for people who can get pregnant. “All pregnancies are different,” says Jennifer Pepper, CEO and president of CHOICES. That’s why the center provides everything from midwife-assisted births to high-risk pregnancy care to prenatal classes—and, since abortion was banned in the state in 2022, abortions at their sister location three hours away in Carbondale, Illinois. (Pepper says CHOICES is the only nonprofit in the country where both birth and abortion take place. And after Dobbs, “we could not stomach the idea that [abortion] patients wouldn’t have anywhere to go,” she says.) Teigen was moved by how the clinic felt so “open and welcoming and airy and light,” with a “sisterhood” that was far from “the coldness” of her own hospital experience. “It never crossed my mind that I could give birth on all fours, or be in a tub at a birthing center,” she said. She saw a better way to give abortion care, too. When Pepper told Teigen she got her start at CHOICES as an abortion doula, Teigen said, “I can’t tell you how much I would have appreciated an abortion doula,” someone to explain “what was happening with my body.” Tennessee also has the highest rate of maternal mortality in the country—and so access to supportive birth care can mean the difference between life and death, particularly for Black women. One Black woman in the prenatal class, Jasmine, recalled a conversation with her doula at CHOICES that started with a heartbreaking wish—“First off, I don’t want to die”—and ended with her having a “beautiful experience” delivering her baby. “Every single woman deserves that level of care in America,” Teigen says. “This is what care looks like—people listening to you, and treating your body and your choices with dignity.” WATCH TEIGEN’S VISIT TO CHOICES HERE:PRODUCER/DIRECTOR/EDITOR: EMILY MURNANE PRODUCED WITH SUPPORT FROM POP CULTURE COLLABORATIVE, AS PART OF THE UNITED STATES OF ABORTION SERIES.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Are women really being “coerced” into abortions?

Greetings, Meteor readers,

It is bitter cold in much of the U.S. due to an Arctic blast, which seems like an appropriate way for Mother Nature to celebrate the first anniversary of Trump 2.0. Keep your fam and friends close this week (and for the next three years), because it’s near-uninhabitable out there.

Today, we’re teaming up with Jessica Valenti—friend of The Meteor and founder of Abortion, Every Day—on a fresh series of videos demystifying anti-abortion speak. Plus, a history-making governorship begins, and a little bit of justice for Tylenol.

Choosing coziness,

Nona Willis Aronowitz

WHAT'S GOING ON

Who’s coercing whom?: How does the term “coerced abortions” make you feel? Sounds horrible, right? Perhaps something an abusive parent or boyfriend would perpetrate against a vulnerable woman? The phrase—crafted to elicit this precise reaction—is the latest bit of lingo anti-abortion extremists are using to make Americans think that abortion hurts women. If it sounds familiar, you may have encountered it in Republican talking points, lawsuits and state laws—or heard conservatives like Sen. Bill Cassidy (R.-La.) and Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill mention it just last week during a Senate hearing meant to discredit abortion pills. The pills, Cassidy claimed, go “straight to [an abuser’s] mailbox, no questions asked, and then they coerce the woman to take it … Think of the women, the girls in abusive relationships, being trafficked whose voice is being silent.”

OME ANTI-CHOICE PROTESTERS IN 2022 WIELDING THE LANGUAGE OF COERCION. (CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES)

Again: Sounds awful. But in a new edition of our series Anti-Abortion Glossary—in which Abortion, Every Day’s Jessica Valenti unpacks the misleading, misogynist terms used by the anti-abortion movement—Valenti explains that this kind of rhetoric is being specifically used to target doctors who provide abortion medication, or, as in one Louisiana case, a mother who helped her teenage daughter obtain abortion care.

To be clear, some abusers absolutely do force their partners to end a pregnancy. But in a post-Roe world, it is vastly more common that women will be coerced into continuing a pregnancy—either by an abusive partner, or, in the case of abortion bans, by the state itself. In fact, a study from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that abortion bans worsen intimate partner violence by as much as 10 percent. And sometimes, the government helps: in one case out of Texas, police used 83,000 cameras to track down an abortion patient because her abuser turned her in.

So why are conservatives so obsessed with “abortion coercion” when forced pregnancy is a far greater problem? Valenti’s reporting found that in 2023, anti-abortion leaders pinpointed “coercion” as their most effective tool to justify abortion bans—which, after all, are deeply unpopular with most Americans. “The new Republican message must be clear. No woman should ever be subjected to an unwanted abortion,” advised David Reardon of Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America in an opinion piece for The Hill. Valenti sees right through this strategy. “They figured that pretending to care about coercion might make it seem like their laws are protecting women,” Valenti says. “They’re not.”

New episodes of Anti-Abortion Glossary will be dropping every Tuesday on Instagram. Watch here:

AND:

- Speaking of Arctic blasts: Thousands of Greenlanders (a number that constitutes a major chunk of the country’s population) marched in the streets on Saturday to protest Trump’s threat of invading the country. Among the protesters was Tillie Martinussen, a former member of parliament, who’s called the U.S. “greedy” and accused Trump of surrounding himself with “white power people.” The American government “started out as sort of touting themselves as [Greenland’s] friends and allies,” she told EuroNews at the protest. "And now they're just plain out threatening us.”

GREENLANDERS TURNED OUT ON SATURDAY AGAINST TRUMP’S IMPERIALIST PLANS. (CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES)

- Speaking of Arctic blasts: Thousands of Greenlanders (a number that constitutes a major chunk of the country’s population) marched in the streets on Saturday to protest Trump’s threat of invading the country. Among the protesters was Tillie Martinussen, a former member of parliament, who’s called the U.S. “greedy” and accused Trump of surrounding himself with “white power people.” The American government “started out as sort of touting themselves as [Greenland’s] friends and allies,” she told EuroNews at the protest. "And now they're just plain out threatening us.”

- Virginia’s first woman governor, Democrat and former CIA officer Abigail Spanberger, was sworn in on Saturday, and she made it her first order of business to repeal her predecessor’s order to cooperate with ICE. “We will focus on the security and safety of all our neighbors,” she promised in her inauguration speech. “And in Virginia, our hardworking, law abiding immigrant neighbors will know that…we mean them, too.” Also sworn in: Ghazala Hashmi, Spanberger’s lieutenant governor, who’s the first Muslim woman ever elected to state office.

- A new scientific study published in the medical journal The Lancet should reassure pregnant women that they need not “tough it out,” as our esteemed president

andTrump recently advised: In a review of more than three dozen studies, the researchers found no link between acetaminophen use during pregnancy and autism.maternal health expert - There’s no such thing as too much Magic Mike, as New Yorkers will soon discover.

- Heads up: a new epithet is spreading on the far-right to describe Renee Good and those close to her. Think we’ll take “organized gangs of wine moms,” please and thank you.

- Still pissed? Allow us to suggest a rage room.

- Prefer to be anesthetized instead? Subscribe to Collier Meyerson’s new Substack, Soothe Operator, a place to “look away from the sun, briefly,” because “it’s important to go soft in order to go even harder.”

The nurses will not back down

NEWSLETTER

January 15, 2026 Hi there, Meteor readers, The 2016 nostalgia dominating my social feeds has me in my feelings today. I’m thinking about all the protests that year, now overshadowed by the acute tragedy of Donald Trump’s victory that fall. In America, there were the Black Lives Matter marches condemning the murders of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, and the students who took to the streets after Stanford rapist Brock Turner’s lighter-than-air sentencing. Overseas, there were the Black Monday strikes in Poland against proposed abortion bans, anti-corruption demonstrations in Brazil, and millions-deep marches following Brexit. Maybe it’s because I was younger, or because I’d been lulled by the dulcet tones of Obama’s rhetoric, but my sense of indignation was fresher back then. Hotter. More vivid. This week, as the powers that be attempt to quash dissent both here and abroad, I’m channeling that energy anew.  Today, Meteor contributor Ann Vettikkal brings us a dispatch from the historic nurse’s strike in New York City. Plus, a tribute to an unsung civil rights hero, and your weekend reading. 2016 on the scene, Nona Willis Aronowitz  WHAT’S GOING ON“We’re here for our safety”: “What do we want? A fair contract! When do we want it? Now!” This past Tuesday morning, a sea of demonstrators in red surrounded Columbia University Irving Medical Center demanding a fair contract prioritizing patient and nurse safety. They chanted and struck cowbells; one sign read, “Staffing so unsafe, Florence Nightingale is rolling in her grave.” Shows of solidarity in the form of honks, cheers, and salsa music echoed throughout Washington Heights.  NURSES INVOKING THE GOAT, FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE. CREDIT: GETTY IMAGESThe largest nurses’ strike in New York City’s history has now entered its fourth day. On Monday morning, nearly 15,000 nurses walked out of the Montefiore Medical Center and multiple hospitals in the New York-Presbyterian and Mount Sinai Health System network. The nurse’s union, New York State Nurses Association, says management refuses to budge on key issues. (“Here’s a pebble, here’s a little grain of salt” is how one nurse characterized management’s response.) The union says the strike is focused on protecting nurses’ healthcare benefits, safeguards against workplace violence, and safe staffing mandates, which ensures enough nurses are scheduled each day to deliver safe, quality patient care. Joe Solmonese, a spokesperson for Montefiore Medical Center, called their requests “reckless”; a statement from Mount Sinai said NYSNA refused to “move on from its extreme economic demands” for significant pay raises. “The hospitals take advantage [of the fact] that we are the ones that actually care about our patients,” said Beth Loudin, a pediatric nurse and president of the bargaining unit at New York-Presbyterian, who was picketing on Tuesday. “They don’t think we would go outside and fight for the things that actually protect us and protect our patients.”  BETH LOUDIN AT THE PICKET LINE. CREDIT: ANN VETTIKKALLoudin became a nurse a decade ago because of her passion for listening and advocating for people in difficult times. She joined the union four years ago and eventually rose to leadership. She pointed to the gains a smaller nurses’ strike involving Mount Sinai and Montefiore won three years ago—which included hiring additional nurses, and implementing minimum nurse-to-patient ratios—as a precedent for this “historic” strike. There are plans to head back to the negotiation table this evening, according to a NYSNA statement released this morning. In addition to their original demands, NYSNA charges that Mount Sinai “unlawfully terminated” and disciplined several outspoken nurses in the days leading up to the strike. Several politicians have shown their support, including Mayor Zohran Mamdani, who joined the picket and donned a red NYSNA scarf on the first day of the strike. “These nurses are here for New Yorkers,” Mamdani said in a statement to the press. “They show up and all they are asking for in return is dignity, respect, and the fair pay and treatment that they deserve.” This strike comes on the heels of many other nurses’ strikes across the country. Given that nursing is the number one occupation for women, these fights could meaningfully move the needle on the overall quality of life for women in this country. “It’s now a wave,” Loudin said. “We’re here for the patients. We’re here for our safety. I hope that wave just continues to grow and grow and grow.” —Ann Vettikkal AND:

CLAUDETTE COLVIN IN 1998. CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES

WEEKEND READING AND LISTENING 📚 🔊On systemic racism: Why this Texas county is the deadliest place for Black mothers to have a baby. (Capital B) On frenemies: Dayna Tortorici untangles the many divisions that have torn feminists apart for 200 years. (n +1) On “the last American dream”: Please enjoy this exceedingly delightful interview with comedian Robby Hoffman on masculinity, her Hasidic upbringing, and rich-people guilt. (Talk Easy with Sam Fragoso)

|

![]()

Courage and cigarettes

NEWSLETTER

January 15, 2026 Greetings, Meteor readers, My kid is getting her tonsils taken out this week. Any parents out there with tips on how to survive the recovery period, I welcome the guidance. On to bigger things. In today’s newsletter, protests in Iran have already reached a terrifying death count. Plus, the government is investigating Renee Nicole Good’s widow instead of focusing on her killer. Popsicles for the apocalypse, Shannon Melero  WHAT’S GOING ONA history of resilience: At the end of December, shopkeepers and business owners in Tehran shut down their stores and took to the streets in protest. Within hours, a chant at the heart of the protest had spread across the city: “Our money is worth less.” What began as a localized economic complaint has grown into a nationwide anti-government protest that has reportedly claimed the lives of thousands of Iranians. To outside observers—especially those of us caught up in our own country’s headlines—this was a startling escalation. But for those living and working in Tehran, the writing was on the wall for some time. The Iranian economy has been in crisis mode for months: sanctions from the U.S., a 12-day war with Israel, water shortages, and in December—apparently the last straw—Iran’s currency, the rial, hit an all-time low. In an initial response to the protests, the Iranian government offered a monthly stipend to alleviate financial woes that was equivalent to seven U.S. dollars. It was an insulting band-aid. And as protests continue, Iran’s leaders have resorted to suppression and violence, attempting to keep Iranians quiet with internet blackouts, imprisonment, and murder by officials of the regime. And while all Iranians are suffering as a result of economic and political instability, this is yet another situation in which women will suffer the most. A UN Women report from 2024 found that Iranian women are more than twice as likely to be unemployed as men. In times of political upheaval, those numbers—along with sexual and physical violence against women—are expected to worsen. We have all seen this before. Time after time, the Iranian people have risen up against their leaders despite being met with the cruelest response. In 2022, after the killing of Mahsa Amini, which sparked the Woman, Life, Freedom movement. In 2021, over water shortages. In 2019, over fuel prices. In 2009, over questionable election results. But some Iranians who spoke to the New York Times said that these protests felt more powerful than even those of 2022 because they have captured Iranians from all walks of life. Young women have been front and center; the internet is full of images of Iranian women using burning pictures of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to light their cigarettes. Conservative and rural Iranians—who for the most part remained on the sidelines during the Women, Life, Freedom movement—are making themselves heard now. “We can see from the news and from some government reactions that this regime is terrified to its bones,” one protester in Tehran told a Times reporter. Many in the streets, on the other hand, are projecting fearlessness. “We are not afraid,” said Sarira Karimi, a University of Tehran student who was arrested last month, “because we are together.” The Trump administration has been keeping an eye on the situation, and earlier today, the president suggested that he was open to an airstrike, writing on Truth Social that the U.S. was “locked and loaded” and that “help was on the way” for protesters (excuse us?). He added that the military was reviewing “some very strong options.” No mention yet if Trump intends to be the acting president of both Venezuela and Iran, but it wouldn’t surprise anyone. AND:

PROTESTORS IN MINNEAPOLIS THE DAY AFTER GOOD’S MURDER (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

OF COURSE THE GAY SHEEP ARE SERVING LOOKS TO THE CAMERA (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Renee Nicole, and Keith, and Marimar, and...

January 9, 2026 Hey there, Meteor readers, Anyone else already getting impatient waiting for Heated Rivalry, Season Two? We NEED to get back to the cottage.  In today’s newsletter, we look at the story that’s on all our minds today—the murder of Renee Nicole Good—and the long road of violence that preceded it. Plus, a moment of good news for parents, and your weekend reading list. One day at a time, The Meteor Team  WHAT'S GOING ONA growing list of names: Yesterday, a masked ICE agent in Minneapolis shot and killed Renee Nicole Good, who had allegedly been blocking agents from entering her neighborhood. Shortly after the shooting, a Department of Homeland Security spokesperson referred to Good as a “violent rioter” and called the killing an act of self-defense. DHS Secretary Kristi Noem even suggested that Good was part of a group carrying out a “domestic act of terrorism” using vehicles as weapons. But video from the scene shows Good giving way to federal vehicles and trying to respond to conflicting orders from DHS agents, shortly before she was approached and shot through her windshield. Witnesses to the murder have also contradicted DHS’s account of what happened, and video also appears to show ICE preventing medical personnel from nearing the scene. Good’s murder has sparked protests in Minneapolis and calls for investigations into ICE’s tactics. Renee Nicole Good was a parent. Just like Keith Porter, who was shot and killed by an off-duty ICE officer in December for reportedly not complying with an order. Renee Nicole Good had a life, a family, a job. Just like Silverio Villegas Gonzalez, who was shot and killed by ICE agents during a traffic stop in September. Renee Nicole Good was sitting in her car, just like Marimar Martinez, a teaching assistant in Chicago who was shot five times by ICE agents in October. (Miraculously, Martinez survived.) Renee Nicole Good’s community was being terrorized by a violent group of thugs hiding behind masks and the emblem of a federal agency—just like communities in Boyle Heights, Westlake, Santa Ana, Pasadena, and Chicago. And that’s not even to speak of what happens where videos rarely record: In 2025, 32 people died while in ICE custody—the most in more than two decades. Movements in America often gain traction after a horrific event spurs people into action. The violence has to be so profound, so unbearable, or so vividly recorded to shake us from a passive state. But those boiling points are never the first incidents. Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi launched Black Lives Matter back in 2013, after the man who killed Trayvon Martin was acquitted—seven years before the murder of George Floyd sparked massive protests across the country. Tarana Burke amplified stories of sexual assault and harassment for more than a decade before reporters exposed Harvey Weinstein’s crimes and MeToo went viral. The question I find myself asking is: Will Renee Nicole Good be the one? Will her murder be the turning point for us to stay in the streets, for judges to intervene, for any lawmaker still waffling to decide “no more”? Or will she blend in with the rest of the violence? A month from now, will we forget her name as we’ve forgotten Keith, Silverio, Marimar, and the dozens of others who never had their moment in the national news spotlight? How much does the body count have to rise for every last person to flood the streets for justice? Because it must be all of us. Our elected leaders are not equipped to take on this task alone. Rep. Ayanna Pressley made her stand and demanded an investigation into the killing of Renee Nicole Good; the GOP blocked it. Former Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot is launching an ICE Accountability Project, which is a step in the right direction, and Rep. Robin Kelly is filing articles of impeachment against DHS Secretary Kristi Noem. But between 2015 and 2021, ICE agents were involved in 23 fatal shootings. No agents were indicted. Will this be the year we stop at one? AND:

A POSTCARD FROM MAMDANISTAN 😘 (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

WEEKEND READING 📚On history: On the heels of a protester’s violent death at the hands of law enforcement, it might be useful to reread Jill Lepore’s 2020 piece on whether we still recall the lessons learned in blood at Kent State. (The New Yorker) On healing: There are glimmers of hope for the uninsured in America. (The Baffler) On heroes: To celebrate Wyoming’s recent abortion win, here’s a profile of Julie Burkhart, an unstoppable abortion care provider in the state. Even an arsonist burning down her clinic wasn’t enough to slow her down. (The Story Exchange)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Tears, Joy, and Fear

January 7, 2026 Salutations, Meteor readers, Happy New Year, friends, it’s good to see you all again. We hope you had a lovely stretch of time off from the real world and are ready to jump back into the massive amounts of everything going on. In today’s newsletter, one of our colleagues shares a personal reflection on what this past week has been like as a Venezuelan living in the United States. Plus, we mourn the loss of a maternal health advocate. Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON

I'm Anti-Trump and Venezuelan. This Week Has Been ComplicatedMy heart is celebrating while my brain sees the bigger picture. MADURO AND HIS WIFE ON THEIR WAY TO A FEDERAL COURTHOUSE IN NEW YORK. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) On January 3rd, the U.S. seized Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife in a military operation that shocked the world. The reaction from many Americans, who have lived through this playbook before, was outrage. The arrest of Maduro and his arraignment in New York courts has been perceived as an attempted regime change, a violation of international law, and an oil grab—all of which, to be clear, it is. (And there’s probably more madness ahead, given Trump’s comments about how “we need Greenland.”) So what does it all feel like for Venezuelans? After Trump declared that he plans to “run” Venezuela, many are fearing for their safety. At the same time, some Venezuelans in the United States are celebrating the removal of an oppressive dictator from power. For our colleague Bianca—a progressive Venezuelan living in the U.S., who asked that we withhold her last name due to privacy concerns—the moment was quite complex. Here’s what the last few days have been like for her. I'm 100 percent Venezuelan, born in Caracas. I grew up going to El Ávila National Park and the beaches of Margarita Island and just enjoying my country. But when [former president] Hugo Chavez got into power in 1998, the whole country was sort of panicking because of the authoritarian policies. Protests started. Repression and political polarization got gradually worse. Friends and family were put in jail simply for expressing their views. By 2007 or so, media suppression intensified; If The Meteor were in Venezuela, everybody [working here] would be in jail. I was part of the first wave of Venezuelans who left, although much of my family stayed. When I got to Miami in 2001, when I was 21, I totally disconnected from my Venezuelan life. For a decade, I just felt like “I don’t want to deal with this”—kind of what people are doing now in the U.S. It was too much and too painful. Then the 2014 protests happened [sparked by an attempted rape of a student in San Cristobal]. The government was killing students in the streets. That’s when I decided to go to Venezuela with my camera, so I could document the reality of what was happening. Public opinion in the U.S. seemed to frame the student protesters as privileged Republicans. When I started interviewing these students, I discovered that was not true. I met kids from the slums of Venezuela, 15 or 16 years old, narrating their torture incidents in prison. I realized it wasn't a left versus right thing–it was a human rights thing. VENEZUELANS OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED NATIONS OFFICE IN CARACAS DURING THE 2014 PROTESTS. (PHOTO BY BIANCA) These kids were just begging the UN to come help, and they never did. After that, I came back to the U.S. and dedicated myself to social justice. I am a Democrat who is against authoritarian regimes, unfair elections, media censorship, and political repression. I've lost [Venezuelan] friends and family because I was a Bernie supporter, and they cannot believe how I can support Bernie as a socialist [because Chavez and his successor Nicolás Maduro were socialist]. Which was why it felt weird to see Trump’s tweet about how Maduro had been captured. Trump’s tweets usually have a horrible, disgusting effect on my heart, but this is the one time a Trump tweet made me incredibly happy. I woke up my mom and gave her the biggest hug and we both started crying. It finally felt like a little bit of justice. I can see why other left-leaning people in the U.S. are scared that this is going to become another Iraq–especially coming from Trump. I saw what happened with Afghanistan and Iraq, and I was against all of it. But I am disappointed to see my flag being used to push agendas; I’ve seen non-Venezuelan protesters [in the U.S.] with Venezuelan flags holding signs saying “Free Maduro.” And we have been screaming for help for years. Some of the arguments [point out that] this violates international law. Okay, but where was the international law when we were asking the UN to come, or when [Maduro] stole the election from us last year, or when they were massacring kids? Where was the international law when we were asking for so much? BIANCA IN 2014 WITH A PROTESTOR WHO WAS IMPRISONED UNDER THE MADURO REGIME. (PHOTO BY BIANCA) We are in a moment where we have to learn how to hold two opposing truths at once. My heart is celebrating while my brain is carefully thinking through the bigger picture. We deserve this joy after so many years. But there is much more to do to re-establish democracy in my country, and I’d be shocked if Trump were the person to do it. —as told to Nona Willis Aronowitz  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()