How to Fight Autocracy, From the Activists Who've Done It

BY MEGAN CARPENTIER

When Donald Trump vowed in December 2023 to be a dictator “on day one,” his aides later clarified that he “was simply trying to trigger the left and the media.” Nonetheless, exit polls showed that half of voters “said they were ‘very concerned’ that another Trump presidency would bring the U.S. closer to authoritarianism,” even though some voted for him anyway.

In the weeks since the election, democracy advocates have raised the alarm about the possibility that, after nearly 250 years, the American system of constitutional governance may be compromised. Many people are worried that Trump will try to hold onto office illegally in 2029; he’s told voters, special interest groups, and House Republicans he’s considering an unconstitutional third term. Critics note his hostility to the free press, his early demands that all his appointments skip confirmation hearings (to which Senate Republicans currently seem unlikely to acquiesce), and his promises to use the Department of Justice to go after perceived political enemies.

Looking at history, the worry that Trump could destroy some of the fundamental guarantees of democracy are not without precedent: All around the world, voters in democratic countries have elected leaders who then undermined the very systems that brought them into power—including the 20th century’s most infamous authoritarian, Adolf Hitler.

How does that happen? What lessons can—and should—Americans learn from other countries which have recent experience with authoritarian rule? Given that scholars have repeatedly found that authoritarian countries are worse for women’s equality, this guidance feels more needed than ever.

So we asked the advice of a few activists from across the globe who know what it’s like when authoritarianism comes your way.

“People exchange their freedoms without actually realizing the consequences for everybody.”

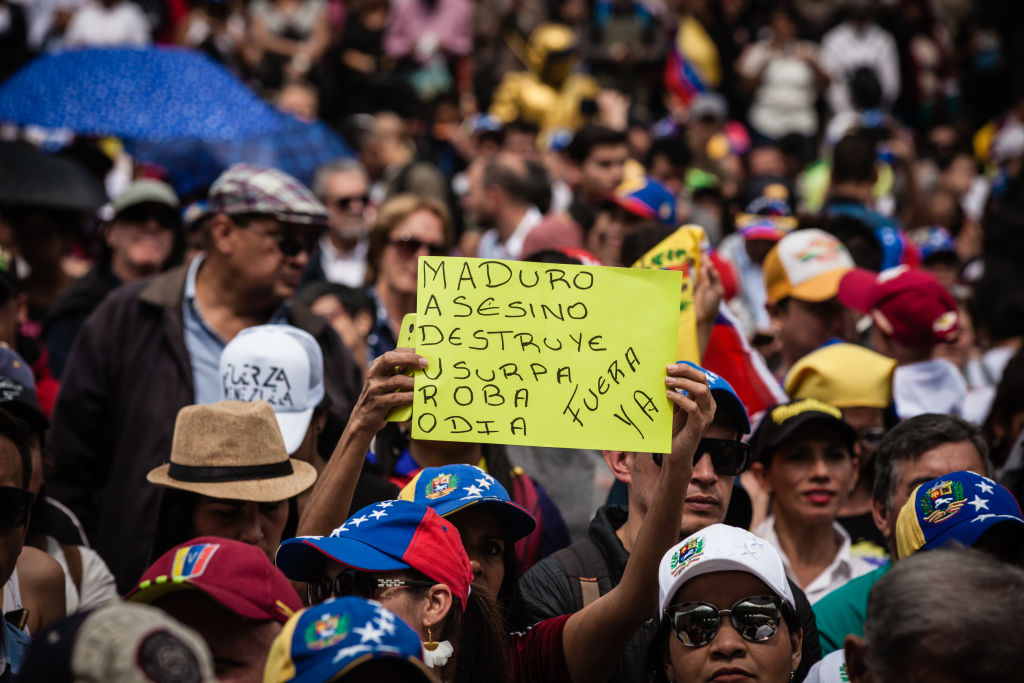

—Génesis Dávila, founder and president of Defiende Venezuela. In Venezuela, current president Nicolás Maduro—handpicked successor of autocrat Hugo Chávez—presides over an authoritarian regime, and recently declared victory in an election he is accused of rigging.

“Something that we couldn't learn on time in Venezuela is that polarization is a poison for the entire society. When we had Chávez and then Maduro in power, they targeted the opposition as enemies and, when they did that, then the opposition also targeted them and their supporters as enemies. The opposition would say Chávez supporters were not smart people, that their values were against the country’s.

“It worked in favor of Chávez and Maduro. I would not want to support someone who is attacking me. I would not want to support someone who believes that I'm not smart. I would not want to support someone who thinks that my values are wrong and their values are right.

“Chávez came to power with the support of the people [but]...he took control of the judiciary and the legislative branch. He announced limitations on freedom of speech; he announced the reform of the Constitution. At the end, he was pretty much able to do whatever he wanted without any resistance. He had 100 percent impunity. [And under Chávez and then Maduro], we moved from being a strong democracy with a strong economy to one of the poorest countries in our region.

“We cannot perceive our fellow citizens as our enemies. We have different perspectives, different values, but we must be willing to find common ground. We need to create bridges, and we need to help them to walk to the other side—but we cannot push them, and we cannot attack them.”

“You can't protect democracy if you're not offering a really inclusive social and economic agenda.”

—Gábor Scheiring, Assistant Professor of Comparative Politics at Georgetown University in Qatar and a former member of the National Assembly in Hungary, where Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has ushered in what the European Parliament has denounced as an “electoral autocracy.”

“I'm a huge supporter of liberal democracy and institutions, but you can't really protect those cherished liberal institutions by just talking about how important it is to have a constitutional court and how important media pluralism is. The overwhelming majority of people don't really think in these terms. They are concerned about inflation and real wages and unemployment and inequality, and that's where you need credibility if you're trying to represent those masses.

“So, the old elitist ways of doing progressive politics will not help you. You can’t just continue talking about the values of democracy, as opposed to talking about issues that matter to people. That's just not working. It's not helpful.

“You need to convey a message of significant change, and do that in a credible way….Beyond that, in the U.S., if you have any friends who have a lot of money and can use it to support significant, large, liberally-oriented media outlets, I think that's super important….If we’re frank, conservative billionaires, they invest in conservative media, even if it doesn't pay out immediately. Liberal billionaires in Hungary, they just did not really care to help sustain non-right-wing media. And I think that's a huge, huge problem.”

“As long as people remain organized, there is hope.”

—Halil Yenigun, Associate Director, Stanford University’s Sohaib and Sara Abbasii Program in Islamic Studies, and former professor in Turkey, where President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s time in office has generally been characterized as a movement away from democracy.

“There are a few basic differences between the Turkish government and the American one today that favor American democracy.

“One is that the U.S. judiciary is still a lot more independent than Turkey’s ever was. So even when Trump transgresses certain limits, some conservative justices still stand up against him, like they did with the election fraud claims. The second one is that the U.S. is a federal government, and federalism still creates some kind of counter-force to a centralized, authoritarian government. Don’t take the institutions for granted. Don't take checks and balances for granted.

“Another institutional mechanism [in both the U.S. and Turkey] is the opposition party organization. Turkey had a multiparty democracy before President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was first elected, and, even after, the opposition party organizations did not give up….Each and every election, they just continued fighting back.

“Even though in Turkey, we did not have the same kind of strong civil society as in the U.S.—we don’t have as many NGOs—civil society proved to be a very important channel for people to remain organized. There are still these openings to express opposition to the regime, like Pride Day and especially the women's movement and the annual Women’s March. [That] movement might seem as though it is about a single issue like women's rights, but it serves as a channel for people to vent their resentment against repression.

“These pockets of resistance are very important, I think, to prove that people can still fight back.”

“We realized that we needed to inform people what human rights are.”

—Cristina Palabay, secretary general of the human-rights organization Karapatan in the Philippines, where former president Rodrigo Duterte’s term from 2016 to 2022 was characterized by extrajudicial killings, human rights abuses, efforts to change the country’s constitution, and more.

“How Duterte spoke about human rights was, ‘OK drug addicts are not humans, They are animals.’ This was the dehumanization in which the administration was engaging.

“We realized that we needed to go back to basics, to inform people what human rights are. We had to explain that human rights are more than what is written in the Constitution—more than just legal rights. Human rights are the right to a dignified life, the right to food, the right to just wages, the right to live at all. People can have a basic understanding of human rights when it is spoken about in a way that is easily understandable to them.

“But, as we were educating people, the situation kept getting worse. When kids started to get killed in the drug war, that's when people started to think, OK, so, this is not just about drug addicts. And then, of course, he went after the human rights defenders and he took a militarist approach during the pandemic.

“Based on this education, people started to question the dehumanization of people. And that’s when we realized that Duterte’s propaganda was not as widespread a success.

“It became a defining moment for many of us—civil society, social movements, journalists, even artists—to all come together to mount some kind of pushback, including online. And we did that.”

Megan Carpentier is a freelance writer and editor. She is an alumna of NBC News, The Guardian, Talking Points Memo, and Jezebel, among others, and her byline has appeared in Foreign Policy, Ms. Magazine, Rolling Stone, Esquire, Glamour, and The New Republic.

The Pros and Cons of Making Wegovy More Accessible

November 26, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, It recently came to my attention that I have an “odd” choice of stuffing for my turkey. I am curious to know what y’all are putting in yours, and I need a solid explanation as to why the answer is not ground beef, which is what is in my bird. This is a question of national importance. In today’s newsletter, we’re talking about a potentially game-changing proposal for weight-loss drugs and the banner year women’s soccer just had. Plus, a little weekend reading to get you through the holiday. Where’s the beef (if not in the turkey), Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONWegovy for all?: Today, the Biden administration proposed that Medicaid and Medicare cover weight-loss drugs like Wegovy and Zepbound. If the proposal becomes official, seven million more Medicaid and Medicare patients deemed “obese” would have access to these drugs. (Both plans already cover drugs like Ozempic for treating type 2 diabetes, but prohibit coverage for medications designed specifically for weight loss.) The proposal’s fate is far from certain; Trump’s pick for health secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. is against use of the drugs. But the proposal itself shows just how much these weight-loss drugs have penetrated American life. At this point, roughly six percent of all American adults (that's about 15 million people) have used these medications—the majority of them women. If the drugs become more affordable thanks to this coverage, those numbers will almost certainly grow. That accessibility, of course, is a good thing: Everyone deserves equal access to medicine, period. But the widespread use of these particular medicines raises other issues, too—like the threat of “Ozempic coercion,” as fat activist Virgie Tovar put it to Samhita Mukhopadhyay in The Meteor last May, in which weight-loss drugs become yet another tool women feel pressured to take in order to change their bodies. And of course, if this or any other administration wanted to do one simple thing to improve the health of citizens, hey, there’s always universal healthcare! Even before Trump The Sequel was on the horizon, it was clear that that was not gonna happen anytime soon, but let’s not lose sight of it as a long-term goal—way more effective, Tovar notes in that interview, than all the weight-loss drugs in the world. Soccer’s huge year: The 2024 NWSL season has officially come to a close, with the Orlando Pride bringing home the big trophy for the first time in club history. But aside from the win and this beautiful moment between Pride star Marta and her mother, the championship caps off a breakthrough year for women’s soccer. The NWSL championship was held in the newly opened CPKC Stadium, the world’s first stadium built specifically for women’s soccer. And 2024 is also the year of Michelle Kang’s record-shattering investment in the sport—the three-team owner gifted U.S. Soccer $30 million over the next five years. According to U.S. Soccer, that’s the largest philanthropic investment made to women's and girls’ soccer programs in the organization’s 111-year history. So not only is everyone watching women’s soccer, but everyone’s investing in it. Took them long enough.  MAY WE ALL FIND SOMEONE WHO LOOKS AT US THE WAY MARTA IS LOOKING AT THIS TROPHY. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) AND:

WEEKEND READING (because the weekend starts tomorrow) 📚On “the happiest ending possible”: A horrifying mix-up during IVF created lasting trauma—but also an unshakeable bond between two families. (New York Times magazine) On exhaustion: After this year’s election, a large number of Black women organizers are thinking of taking a step back from their work. That could have unexpected consequences for the American political system. (NPR) On courage: When 12-year-old Taylor Cadle told police she was being sexually abused, they didn’t believe her. So she took the investigation into her own hands. (Mother Jones)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Sarah McBride Will "Follow the Rules." Girl, Why?

November 21, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, It’s been a difficult week for anyone following the news cycle. That could apply to every week this year, but these last few days have really had some extra bad umph in them. Please do something this weekend to catch your breath. In today’s newsletter, Bailey Wayne Hundl walks us through the ongoing bathroom battle between Rep. Sarah McBride and her GOP colleagues. Plus more trouble brewing in the land of Trump appointees and your weekend reading list. Inhaling and exhaling, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONYou gotta fight for your rights: As you may have heard, Speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA) announced a new policy yesterday: On Capitol Hill, only some women will be allowed to use the women’s restroom. The announcement follows the introduction by Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC) of a bathroom bill targeting Sarah McBride, the first openly transgender person elected to serve in Congress. McBride responded to the policy on social media, writing, “I’m not here to fight about bathrooms…I will follow the rules as outlined by Speaker Johnson, even if I disagree with them.” And as a trans person reading this, I guess I’m just wondering…girl, why? Some have interpreted Rep. McBride’s response as a strategic refusal to be baited into a time-wasting debate. But I happen to believe that the fight for trans people to participate in public life is one that should be faced head-on. I used to work in churches; I’ve been on the receiving end of a lot of bullshit policies. And even if they only affected me, I always fought like hell against them—because I knew that if transphobes scored a win against me, they had a chance to do the same to anyone who came after me. Rep. McBride is not just accepting a loss for herself here. Every trans staffer on the Hill just lost the ability to use the restroom at work, and in fact, Rep. Mace has already filed a bill extending the policy to all bathrooms in federal buildings across the country. I want to be so clear: The people who should be fighting against this the hardest are McBride’s allies, on her behalf. And to their (middling) credit, several Democrats have spoken out against the policy—but, unlike the Republicans, they’re not doing anything. “But Bailey, what can they even do?” Something! Anything! McBride could use the women’s restroom anyway. Her allies could use the wrong bathroom in solidarity. Perhaps easiest of all, McBride or her allies could make a public announcement that their private office bathroom is open for any trans staffers to use. This is more important than ever at a time when Democratic leadership is considering dialing down their support for trans people (and some already have). I’m so sick of the learned helplessness Democrats seem to have adopted in the face of rising, unchecked hatred. The day after the election, I wrote about McBride’s win, saying, “It is nice to know that the next time a legislator in a room full of people suggests ‘hey, let’s kill the transes,’ someone will be in that room to say no.” It didn’t occur to me the strategy might be instead: “I may disagree with you killing us, but I will do nothing to stop it.” —Bailey Wayne Hundl AND:

WEEKEND READING 📚On motherhood: Sometimes it's feral! Filmmaker Marielle Heller and her film Nightbitch give moms permission to lean into their inner animal. (The New Yorker) On survival: A new and painful word has entered the villa. “Broligarchy” is the collection of bros preparing to run the U.S. for the next four years. Here are some tips to make it through. (The Power, on Substack) On the hunger of belonging: An Armenian writer reflects on the kaleidoscopic meaning of her family’s mulukhiyah recipes. (Longreads)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Is It a Privilege to Pee?

November 19, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, Remember last week when I said we would be doing a special photos-only send of my Christmas sweater once I finished making it? Well, guess what? We are totally not doing that because we are serious news people and these are serious times, but if you want a little holly in your jolly, you may or may not find it here. In today’s newsletter, we’re talking about bathroom bullies in Congress, Matt Gaetz, and a win in Wyoming. Seriously serious, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONIt’s a privilege to pee (apparently): When I first heard that Delaware lawmaker Sarah McBride had won her election, making her the first openly transgender person to serve in Congress, I turned to my roommate and said, “How long do you think we have until Republicans completely lose their shit?” As it turns out, not long at all. On Monday, South Carolina congresswoman Nancy Mace (R) introduced a resolution banning any members of Congress or House employees from “using single-sex facilities other than those corresponding to their biological sex.” When asked by reporters if the bill was targeting McBride specifically, she responded, “Yes and absolutely, and then some… I’m absolutely 100% gonna stand in the way of any man [sic] who wants to be in a women’s restroom, in our locker rooms, in our changing rooms.”  MCBRIDE AT THE CAPITOL (VIA GETTY) There’s been much ado lately about whether or not all women should be allowed in women’s restrooms, women’s locker rooms, women’s sports. But this conversation has never really been about restrooms. We are witnessing a debate on whether or not trans people should be allowed to exist in public life. If we were all in agreement on that point—if this public panic was truly about women’s safety or the sanctity of your 8th grade daughter’s Little League team—then this conversation would be a logistical one. Those in opposition would propose alternate solutions. They’d have an answer (any answer at all!) for where a grown-ass man with a full beard and a vagina should pee. But they’re not even considering the question. Nancy, if you really want women in Congress to be safer, I’d start focusing your energy on…well, just read the next item. —Bailey Wayne Hundl About that (alleged) abuser: Ever since last week’s bombshell that Matt Gaetz is Trump’s pick for Attorney General, the media has been asking why, exactly, anyone (even Trump) would nominate him. As a refresher: Not only is Gaetz patently unqualified for the job, deeply disliked by his Republican colleagues, and primed to carry out the retribution Trump has been threatening, he’s also been the subject of a House Ethics Committee investigation amid various accusations including sex trafficking and bribery. (Some details from that investigation have already leaked; WaPo reports that two women testified they were paid to have sex with Gaetz.) According to the New York Times, even Trump himself privately acknowledges Gaetz’s uphill struggle in winning the nomination. So the question remains: Why did he nominate this creep in the first place? We have to presume he knew what was in the House investigation and doesn’t care. But analysts suggest there may be something more nefarious at play: The kerfuffle around Gaetz draws attention away from Trump’s other dangerous choices, like anti-vaxxer Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., accused sex offender Pete Hegseth, or Putin darling Tulsi Gabbard. Gaetz makes them all seem less clownish in comparison. The plan may be to lower the bar for nominees, presenting so many extreme choices that the Senate can’t block all of them. So although it’s good news that Gaetz is far from a shoe-in, it’s unsettling that he might help pave the way for some equally abysmal government officials. (And if you too are unsettled, keep calling.) —Nona Willis Aronowitz AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Gaetz, Hegseth, and RFK. Oh my!

November 14, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, I am roughly two days away from finishing a Christmas sweater I started knitting in 2022, so please know that when it’s done you will be receiving a special newsletter that is only pictures of this sweater. I will not be stopped! In today’s newsletter, we are picking ourselves up and reminding ourselves who’s really in charge in this country. Plus a call to greater action for GBV survivors in Kenya and your weekend reading list. All the way from sleeve island, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONThe bad boys club: Donald Trump’s horrifying picks for key government positions continue apace. There’s Stephen Miller for deputy chief of staff, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. for health secretary, Pete Hegseth for defense secretary, and the pick that has produced the most mouth-frothing of all: Matt Gaetz for attorney general. By now you likely know many of the reasons this newly former congressman should not get this job. The alleged sex trafficking for which he was being investigated by the House Ethics Committee. The terribly kept secret of his relationships with underage girls. The legal experience so thin that the Wall Street Journal wrote that his law degree “might as well be a doctorate in outrage theater.” His blindingly white teeth and startling Botox. (Fine, those don't really matter, but they do look freaky.) The one saving grace here, small though it may be, is that even some Republicans say they cannot see a path to Senate confirmation for Gaetz.  THESE TEETH JUST DO NOT OCCUR IN NATURE. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) But! And this is an enormous, Godzilla-sized “but”: Anyone who lived through the Brett Kavanaugh hearings—in which Susan Collins and other Republicans wrung their hands over the accusations of sexual assault, but then voted to confirm him—is right to be cynical about these protestations. Besides, the outrageousness of nominating a potential sex offender to run the justice department means that Trump is doing something intentional here: This is an explicit test of which senators will be loyal to him. But if it’s a test for them, it is also a test for us. Government officials do not work or exist in a vacuum. At least as of today, they are still civil servants, and if we want to stop them from becoming lords of a fiefdom then we must continue the work of demanding better. Organizer Sandra Avalos wrote in Truthout this week, “Our communities are not new to hardship — but we have survived even the harshest conditions, and in those moments, built even more power. We know how to organize, how to protect one another, how to support those facing the brunt of the threats.” In this case, it’s worth remembering that the “what are you going to do? They’re all crooks” reaction to the nomination of Matt Gaetz may be legitimate—but it also lets the Senators whose job it is to do the right thing off the hook, and they don’t deserve that pass. If you live in a state with one of those Republicans expressing even tepid doubts, it’s worth calling them. Quote those doubts back to them. Demand thorough hearings. Pressure your House members to release the ethics report into Gaetz. Remind them in any way you can that they work for us. AND:

WEEKEND READING 📚On men: Looking for a break from toxic masculinity? You may be surprised to find respite in The Golden Bachelorette. (Slate) On the internet: The phrase “your body, my choice,” recently popularized by a Hitler-admiring self-described incel, didn’t come to life overnight—it has a dark and longstanding history, Jia Tolentino explains. (The New Yorker) On the images we keep: One writer’s practice of collecting images from Gaza preserves both the unspeakably bad and the brief moments of good. (The Baffler)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Do We Need to Worry About Susie Wiles and Elise Stefanik? Um. Yeah.

November 12, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, If you haven’t already heard, wildfires are happening right now in parts of New York and New Jersey. For those of you in the area: The lack of rain and increased winds will likely make fires worse, so this is my friendly reminder to follow the rules of fire prevention if you’re in a dry zone. In today’s newsletter, we get to know the newest soon-to-be members of the Cabinet. Plus an uptick in abortion pill purchases and an important update for anyone who still has Thunderstruck playing in their brain. Waiting for rain, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONGirlboss, gaslight, gatekeep the White House: Donald Trump has started announcing his picks for cabinet positions, and before you even have time to ask, yes, we should be concerned about his first-round draft picks. But today, we’re focusing on two of Trump’s high-profile ladies—which is confusing considering that we’re pretty sure J.D. Vance said that women shouldn’t even be working anymore. First up is Susie Wiles, who’ll be the first woman to be the White House chief of staff if she’s confirmed. She was Trump’s campaign manager this year and is known for being incredibly effective, in the worst possible way. A self-described moderate Republican, long-time lobbyist, and political strategist, Wiles was a key figure in getting Ron DeSantis elected governor in 2018. Then, when the two parted ways, she was instrumental in destroying DeSantis’ 2024 presidential attempt in favor of helping Trump secure the nomination. In April, Politico called her the “most feared” political operative in America.  BEHIND EVERY VILE MAN IS A WOMAN WORKING TO UPHOLD POWER STRUCTURES THAT ULTIMATELY WILL NOT SERVE HER. (VIA GETTY) Wiles has been credited with bringing a high level of organization to the 2024 Trump campaign, and with being “a brilliant tactician…who helps her boss to set and achieve their priorities.” And since her boss’s Day One priorities include mass deportations and dismantling environmental protections, Wiles’s apparent efficiency fills me with a soul-crushing fear. Speaking of crushed souls, the next lady on the list is human Babadook Rep. Elise Stefanik, notorious for her congressional inquisitions of college presidents—several of whom lost their jobs—for allegations of antisemitism on campus. (Never mind that she herself has nodded to antisemitic “replacement theory” in her own Trumptastic campaign ads in the past.) Stefanik has now been chosen as the next ambassador to the United Nations, a crucially important post as the UN is dealing with a record number of wars and humanitarian crises across the globe. Her appointment is troubling, considering she has called for a “complete reassessment” of U.S. funding for UN initiatives that provide aid to groups in need, like the millions of women and children displaced by violence who rely on UN supplies and refugee programs.  ELISE STEFANIK GIVING OFF MAJOR BBE, BIG BABADOOK ENERGY. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) While Stefanik doesn’t have the decades-long resume of Susie Wiles (or much international experience, btw), she has something apparently even stronger: unyielding loyalty to Donald Trump. While Wiles may work to implement Trump’s will with as little public messiness as she can manage, Stefanik has already shown her willingness to fuel whatever fire will push forward the MAGA agenda, including stoking fears of anti-semitism at home to justify violence abroad. If you’re old enough to remember Samantha Power, who wrote a brilliant Pulitzer-winning book on genocide before becoming ambassador to the U.N., well—this ain’t that. Looking at these women’s track records and the power positions they’ve been offered, I can safely say I have not been this scared for the future since…last Tuesday. AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

"Was It Foolish to Hope?"

November 8, 2024 Dear Meteor readers, I hope everyone has something—anything—fun planned for this weekend. (I’m taking my little one to her first gymnastics class and can already feel the gold medal.) In today’s newsletter, we’re parsing the aftermath of Tuesday’s election with Brittany Packnett Cunningham and the UNDISTRACTED group chat. Plus, some options if you’re looking for an election break. Onward, Shannon Melero  “WAS IT FOOLISH TO HOPE?”That’s the powerful, poignant question host Brittany Packnett Cunningham posed to group-chat regulars Dr. Brittney Cooper and Dr. David Johns this week on UNDISTRACTED. The morning after Vice President Kamala Harris conceded the election (but not, as she said, “the fight that fueled this campaign”), the three sat down for a raw, honest conversation about everything from “righteous rage” to “deep disappointment” at America’s rejection of a Black South Asian woman candidate in favor of an open white nationalist. We hope you’ll listen to the whole thing; here are some highlights: Brittany Packnett Cunningham on her immediate feelings: "There’s a rage that I have for the deep lack of solidarity, appreciation and fundamental respect for…the Black women who consistently do the custodial work of democracy and get left hanging out to dry every single time. And for me, it is punctuated by the fact that the night before we all gathered at Howard [for the election results], J.D. Vance stood up and said, “We’re going to take out the trash tomorrow…[and] the trash’s name is Kamala Harris.” He was talking about every single one of us in the moment that he did that. And…it barely made a blip. In fact, plenty of people said, That’s exactly what I wanna go vote for. Let me go take out the trash." "We delayed this episode by a day because I didn’t want to come with this energy. [But] I’m still in grief. Not over just a candidate or an election. Not just because…the worst is yet to come. But because there seems to be little, if any, repentance toward the absolute disappointment everybody continues to be to Black women. And every Black woman I talk to is ready to go on strike….So that's where I am today."  “EVERY BLACK WOMAN I TALK TO IS READY TO GO ON STRIKE...” (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Dr. David Johns on hope: "I want us to feel all of our feelings. And…the corollary of that for me is that there’s never been a chapter in the history of our people where our ancestors began or ended with '...and then we conceded,' or '...and then we gave up.' That is not in us." "Also, I am heartened by the reminder that Black people understood the assignment in spite of all the lies that the media tried to tell, blaming Black men. In spite of all of those lies, we, Black men and Black women [by voting overwhelmingly against Trump] demonstrated an understanding of the assignment to continue to care for one another while doing the work of creating the democracy that our ancestors fought and died for, and that we are fighting for today.”  HARRIS SUPPORTERS AT HOWARD UNIVERSITY ON THE DAY OF THE VICE PRESIDENT'S CONCESSION SPEECH (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Dr. Brittney Cooper on how Harris was viewed: "I’m managing rage at the white supremacy and the patriarchy and sexism and misogyny of it all for sure. I’m also managing deep, deep disappointment and fury at some pockets of the left—because I think that I witnessed an abdication of a race/gender analysis that would prepare us for this moment." "The left had this sort of narrative about how she was so much a representative of the Empire that they couldn’t trust her for progressive goals—but they didn’t realize that they were fighting against people who saw her as a Black girl [who] would never be worthy enough to actually run the country. There is no evidence that this country trusted a Black girl with an Asian mama to run it and do it with excellence. Most of the country looked at Kamala and didn’t see a representative of the Empire, but actually saw the opposite—saw a Black girl [who] could never be a sufficient representative of this empire. And that is how they voted." Listen to the full episode of UNDISTRACTED. You won’t be sorry. AND:

JENNIFFER GONZÁLEZ-COLÓN IN 2023. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

WEEKEND READING 📚

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

"I woke up worried for my daughter."

November 6, 2024 Dear Meteor readers, You’re getting this email approximately 12 hours after Donald Trump secured his second presidential victory, and only minutes after Vice President Kamala Harris conceded in front of a tearful crowd at Howard University. Trump’s decisive win is still a fresh wound: We’re only in the earliest minutes of figuring out what it means for not just our democracy but our actual, real lives: how we work, where we are safe, who we need to hold close. As a media outlet, The Meteor tries to bring you reasonably thoughtful stories, analysis and videos. But as a group of real people negotiating emotions, The Meteor had a day like everyone else, and may or may not have typed this from a fetal position on the couch. Rage, disorientation, and heartache for the many people who put their lives on the line for change were all part of the mix. So while there’ll be plenty of time for action steps in the weeks (and, realistically, years) to come, today is personal. In this newsletter, six of my colleagues tell you exactly what today felt like to them. (We did have a no-false-hope rule: “You know we’re not gonna kumbaya our way out of this,” Shannon said at our editorial meeting this morning.) Here are their reflections. And we want to hear yours—find us at [email protected], or, as always, here. Grateful for all of you, Cindi Leive  “We have never been safe.”A Trump win hits different as a tranny. In 2016, I was a 22-year-old gay boy living in Houston, and I was scared. The day after he won, some men in a pickup truck drove by me and yelled, “TRUMP WON, FAGGOT!” And, obviously, that felt bad. But now…? I have an appointment to discuss getting back on estrogen (had to stop after a health scare) set for January 30—ten days after the inauguration. And no, I don’t think gender-affirming care will be outlawed in ten days. (Mind you, I also thought the sexual abuse court decision might make people give half a shit, so what do I know?) But it does have me acutely aware: How much longer do I have? That seems to be the common question for the trans people I’ve been talking to today: How much time do I have to change my name? How soon can I scrape the money together for surgery? How much longer can I stay in the state where I’ve built my home? If this truly is the fabric of the country we live in, will the remainder of my life be measured in decades, years, or weeks?  A national monument of enduring historical significance. And a fort in the background. (Photo courtesy of Bailey Wayne Hundl) I remember the first Trump presidency. I remember how new oppressions would burst from his administration like solar flares—fast, unpredictable, deadly—and burn whichever community happened to be standing in the danger zone. And if the focus of his most recent campaign is any tell, my community’s going to need some SPF 70,000. I feel my cis friends’ knowing gloom. I get texts telling me they’re so sorry. My boyfriend holds me as he describes what he’ll do if anything happens to me. The danger is real, and I’m not the only one who knows it. There are small bright spots, electorally speaking: Zooey Zephyr, an outspoken trans state senator in Montana, won her reelection with 83%. Sarah McBride (D-Del.) will be the first openly transgender congresswoman (although she does, I’m sorry to say, support Israel’s right to “defend itself”). And I am not so naive as to pretend that amassing electoral power is enough to save my community. But it is nice to know that the next time a legislator in a room full of people suggests “hey, let’s kill the transes,” someone will be in that room to say no. But oddly enough, what brings me the most comfort is the knowledge that this country has never had my community’s interests at heart. At best, we have had the illusion of safety with some semi-significant improvements to our material realities. But I’ve always been one pickup truck of men away from becoming a headline. And before I was born, my community had it even worse. And still we loved. And still we held each other close. And still we resisted, and made art, made protest signs, made love, cried, danced, survived another day. I’m reminded so often, but especially today, of these words from queer pastor Hannah Adair Bonner: “We have never been safe, but we have always been brave. We have never been given a space; we have always had to take it.” —Bailey Wayne Hundl, content editor  “I woke up worried for my daughter.”Here are two of the things I kept in mind when I voted last week: my abortions, and my daughter.  Nona and her daughter Dorie at the Jersey Shore. (Photo courtesy of Nona Willis Aronowitz) I’ve had two abortions—one at seven weeks because I didn’t want to have a baby, and one at 14 weeks because I very much wanted to have a baby but had gotten some horrible news from our genetic screening. Both took place in New York, where they were easy to schedule, covered by insurance, and within a few miles of my house. Both times, I envisioned myself living a parallel reality of a woman in an abortion-hostile state. In 2019, when I had my first abortion, I thought about the spate of “heartbeat bills” being proposed across the country, keenly aware that my procedure would have come too late if those bills had been law. In 2024, on the eve of my second, I thought about how my devastation would be compounded by planning an out-of-state abortion without medical guidance, amid work and childcare obligations and my own deep grief. Today, 17 states would have prevented me from having my first abortion, and 19 would have blocked the second. In each case, my life would have been irreparably changed against my will. Yesterday, I hoped that the country would elect a person who believes in every pregnant person’s right to shape their fate. That did not come to pass—even though voters approved seven more ballot initiatives codifying abortion rights, all meaningful victories that reflect abortion’s broad popularity. As I cuddled my oblivious, wriggling toddler this morning, I worried for her future. But I took a teensy bit of solace in her declaration of bodily autonomy as I tried to persuade her to go potty before we left for daycare: “NO, I don’t have to go pee!!!” she screamed. It was her body; I couldn’t make her do anything she didn’t want to do. My job will be to help her keep that sense of agency, that sense of self-ownership, for as long as humanly possible. —Nona Willis Aronowitz, contributing editor  “Sit in that discomfort.”I wish I could tell you that I was shocked by the news that Donald Trump will be the next president of the United States. But I don’t want to lie. I have seen the deep ugliness, the racism, the violence of this country. I have felt the fear of living as a visibly Muslim woman, the dread of being visibly queer, and even changed the way I speak so as to make myself non-threatening to white people. I have lived my entire life under the heavy thumb of a white-nationalist America that, until 2016, went largely unnoticed by those who benefited from it. But now you see it. You see him. You know now without any doubt what has always been waiting just beneath the surface for someone willing to say all of it out loud. Someone willing to say they will reshape this nation for the benefit of white, reactionary, Christian men. And perhaps seeing it in the harsh light of day grips you with fear. For some of us, these sensations are not new. But for many of you reading this, it’s the first time you’ve seen white supremacy so naked, so unabashed. And if you are in the latter group I challenge you to sit with that fact all day today. Sit in that discomfort. Don’t look for something to point to to make all of this somehow feel okay. Spend time in the knowledge that when given the opportunity to say “no” to a fascist, a majority of Americans chose to embrace him. I’ve lived under a blanket of white supremacy for 30 years. You can endure that feeling for 24 hours. And when we are ready to resume the fight—because we are going to fight—my guiding light will be the people of the Young Lords Party of the 1960s and ‘70s who, when everything was working against them, came together to care for their own. This group of young Latine and Black activists in New York and Chicago knew politicians would not save them and so they chose each other. They chose resistance. They chose to change lives. There is nothing stopping each and every single one of us from making that same choice. This is the moment. "El machete no es solo pa' cortar caña." —Shannon Melero, newsletter editor  “We are not the lost ones.” Rebecca and her sister in community building, Caryn Rivers. (Photo courtesy of Rebecca Carroll) For those of us who voted for decency: Decency lost, but we didn’t. We are not the lost ones. We are the ones who fought and will continue to fight for each other with our whole entire selves. As a Black woman in America who is resolutely clear about the work we do and have done for this country, I’m angry AF that a white man protected by the primal callousness of America won. But I am also buoyed by the brilliant fighters who, over the last century, turned community organizing into a collective blueprint for how to be in this world. Toni told us, Jimmie warned us, Octavia predicted this almost to the letter. Our work now is to evolve the language of telling, the tenor of warning, and the vision of predicting by tapping into the reserve of love and fight and compassion created by those of us who did vote for decency. We prioritized the future safety and wellness of each other over everything else. That priority hasn’t changed. —Rebecca Carroll, editor-at-large and founding collective member  “I didn’t realize how hopeful I was.”I know we’ll have endless discussions about what happened and who to blame—a lot of which will be misguided, some of it accurate but hard to hear. I see people on social media saying they knew this would happen. I respect that, but I’m shocked at how legitimately shocked I am. I didn’t realize how hopeful I was that people would not fall for Trump’s chaos again. And it’s hard for me right now to even begin to grapple with what’s to come. But as a writer and a movement journalist, I’m clinging to one thing I know to be true: There is no greater power than of the collective and of standing with each other, and there’s never been a moment in history when that part was easy or handed to us. I’m deeply grateful for every organizer today—every person who protested, door-knocked, talked to people, made art, bore witness to atrocity, and made impossible compromises. That said, I’m not creating today. Today, I’m listening and feeling, wrapping myself in a blanket even though it’s 75 degrees in November, and eating my favorite things while the wisdom comes and the ancestors show us the way. It’s coming. Some may say it’s already here. —Samhita Mukhopadhyay, former editorial director and collective member  “It’s going to be up to them.”Waiting for the girls to wake up was the hardest part. Hearing their footsteps on the stairs, eager for news. Knowing that I’ll have to find words, again, that instill hope and protect their young spirits, but also brace them for the realities of a country and a culture that thinks of them as less than the perfect, beautiful beings they are. Words they’ll remember and return to someday when they need to draw on reserves of strength to keep going in whatever fight they will inevitably be fighting. But this time they know more. They’ve seen more. As South Asian girls, they also see themselves in Kamala — and have now watched her come so close to realizing a dream that may not arrive anytime soon. In 2016, I wrote that I found my hope in their smiles, in the light in their eyes. Today there were no smiles. Today there were tears. The only thing I could do was to look at them and tell them that I still believe. That it’s going to be up to them. That they will be the ones to lead the next generation, with kindness, with integrity, and with love. And that I will be there for them, with them, always. I’ll be fighting too. —Tara Abrahams, head of impact  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

What Everyone Forgets on Election Day

November 4, 2024 Meteor friends, Tomorrow is the big day. We know there’s a lot on the line and we’re processing it all with you. We hope you’re ready to vote for something, and someone, you feel strongly about.  But before we all get swept up in the CNN of it all, let’s go over a few key things it’s easy to forget—both about Election Day and the confusion that is likely to come after. Make your voice heard, Cindi, Nona and Rebecca  IF YOU HAVEN'T VOTED YET... We’ve been saying this a lot in the newsletter when it comes to voting: “Y’all know what to do.” But for those who don’t know what to do—which is understandable, ’cause it’s not always clear!—we’re here to help.

Know your rights. If you’re told you can’t vote, ask to complete a provisional ballot, and learn your rights. And if anyone threatens or tries to block you from voting, report it to the Election Protection Hotline at 866-OUR-VOTE. Intimidation is illegal! IF YOU’VE ALREADY VOTED, BUT WANT TO HELP… POLL WORKERS IN GEORGIA DOING THE SACRED WORK OF SIGNING IN VOTERS DURING EARLY VOTING (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Focus on the people closest to you. Encourage them to vote, offer to watch the kids and drive them to their polling spot. If they have questions about accessibility or what to bring, direct them here. If they have questions about voting more confidentially (which people living in abusive situations may want), direct them here. And if they’re in a place where the lines are seemingly endless, pack them snacks and water.

WHAT TO EXPECT AFTER NOVEMBER 5 KIDS LOVE VOTING! (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Unless there’s an unexpected landslide, we probably won’t know who won the presidential election on Tuesday night. Here are some key things to know for the days and weeks ahead:

And finally, be mindful of inadvertently spreading dis- and misinformation during and after the election—it happens when we’re most confused and agitated. Here is a great resource with a checklist of what to consider before you share links. Let’s be part of the solution!  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

I Was a Sexual-Assault Advocate Under Trump

Yes, it was as bad as it sounds. And no—we can’t go back

By Alisa Sieber

Imagine walking into your office every morning—a room where you’ve listened to countless survivors recount their stories, where the air is often heavy with the weight of trauma. You sit down at your desk, surrounded by the files of people who trusted you to advocate for them, only to look up and see a framed photograph of the leader of your organization—a man who was accused of sexual misconduct.

That was my reality. My commander-in-chief was Donald Trump, the man who openly boasted about grabbing women “by the pussy.” And suddenly, after January 2017, he was at the top of the military chain of command, overseeing everything including the very program where I served as a Sexual Assault Response Coordinator (SARC) in the Marine Corps.

How did I end up here, serving as a victim advocate under a president who openly bragged about violating women’s bodies?

At 17, I joined the Marine Corps on a parental waiver, seeking structure, belonging, and a way to overcome the depression and trauma I carried from past abuse. I had trusted the Corps to make me stronger than my pain, to help me become untouchable. But that trust was misplaced, and I found myself a victim of sexual assault within the organization I thought would protect me. The weight of these experiences grew heavier as I pushed myself harder, hoping the pain would fade.

Eventually, I became a C-130 pilot, flying logistical missions and supporting operations worldwide. Yet, despite my skills, I never felt I truly belonged in the cockpit. Constant pressure in a male-dominated field kept me perpetually on edge. Any sign of struggle was seen as weakness. I felt like I was breaking myself just to perform, overcompensating to hide everything I’d endured.

Midway through my career, I was assigned the role of victim advocate for the Department of Defense’s Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Program. I knew this role could trigger my own unreported trauma, but saying “no” wasn’t an option. Refusing would have disappointed my leadership, who wouldn’t have understood. And I knew survivors needed someone who truly cared, so I took the training to become a victim advocate during the 2016 election.

At that time, I never could have imagined that a perpetrator would rise to commander-in-chief. I had commissioned just as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was repealed, and combat roles had opened to all genders—a glimpse of progress. I was idealistic, believing I could help survivors find the courage to report where I hadn’t, trusting they would be supported by leaders who upheld accountability and respect.

After Trump took office, the culture shifted dramatically. Frequent policy changes and inflammatory rhetoric created tension and uncertainty within units, blurring lines around acceptable behavior. Locker room talk, inappropriate jokes, and divisive comments on gender and sexual orientation reignited divisions we thought were behind us. And my own job got harder: How could we tell survivors they mattered when the man at the top dismissed responsibility and minimized identity, service, and assault? His actions sent a clear message: integrity was no longer a priority.

For survivors like me, that shift was painful. Each day, I worked closely with other military personnel who had survived violence—accompanying them to appointments, guiding them through the judicial process, and bearing witness to their stories. The hardest moments were sitting with them as they unraveled, recounting violations committed by those they trusted—often colleagues who wore the same uniform.

In those vulnerable moments, Trump’s photograph was more than an image. It was a symbol of abandonment, a message that survivors’ pain didn’t matter. Justice felt impossible in a system that seemed to be moving backward. Survivors who dared to speak up were often ostracized, while perpetrators faced minimal consequences.

Each story weighed heavily on me, reminding me daily that the system wasn’t built to save them—or me. By 2019, I left the military, hoping civilian life would lift that burden. But the pain followed. Outside the military, I found that people didn’t want to hear about the dark realities of service or the systemic failures that harm survivors. The same people who claimed to love their country would flip their flags upside down, dismissing my nine years of service because I didn’t share their values. For believing in empathy, justice, and accountability, my experience as a Marine—my skills, my sacrifices—seemed to mean nothing. Once again, I felt silenced. And that silence is not something I want my daughters to inherit.

As I began to share my experiences, other survivors—people I never expected—started opening up to me. One of the most profound moments came recently when my own mother shared a story I had never heard before. At 18, she was drugged, assaulted, and left pregnant. Raised in a strict religious household, she couldn’t turn to her family, fearing punishment. Instead, she found support at Planned Parenthood. If not for her courage, I wouldn’t be here today.

Her story brings everything full circle—showing how bodily autonomy shapes our lives. It reinforces for me that we need leadership grounded in empathy, not just power.

The fight for survivors of military sexual trauma is far from over. With threats like Project 2025 proposing cuts to veterans’ disability benefits, survivors who serve face even greater challenges—alongside active-duty women whose health care autonomy is already limited.

We can’t allow that. I dream of a world where no survivor must live in the shadow of a predator. A world where all of us can stand openly in the light, safe and valued. And we can make that world possible when we vote.

Alisa Sieber is a Marine Corps veteran, former C-130 pilot, and Sexual Assault Response Coordinator (SARC) who served under the Trump administration. Today she is a writer and advocate, she uses her voice to shed light on the systemic challenges survivors face and the importance of leadership that truly values human dignity.