Ozempic, Voguing and Abortion Bans

|

Happy final days of December, Meteor readers, We want to thank you for choosing to spend this last year with us. There are a lot of great newsletters out there, and the fact that so many of you are keeping us in your rotation motivates us to keep getting better. (Speaking of better, you can help us improve by filling out this survey if you’re feeling it!) Before we roll into 2025, we wanted to share some of your (and our) favorite Meteor stories and podcast episodes of the year. Enjoy your break, and you can keep up with us here in the meantime.  Rikers Island is one of the nation’s most notorious jails, and incarcerated trans people there are treated especially inhumanely. But during Pride 2024, Mik Bean reports, Rikers was also the site of the second annual vogue ball for trans incarcerees. “So many ballroom legends and icons have passed through Rikers Island,” notes Jordyn Jay, founder of Black Trans Femmes in the Arts (BTFA), which organized the ball. “I think we came in with the intention of bringing joy and excitement to the women who were detained.” Few things seemed as top of mind this year as weight-loss drugs like Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro. Samhita Mukhopadhyay spoke to fat activist and author Virgie Tovar about how America’s fatphobic culture removes the freedom of choice to lose weight or not. “What amazes me is there are a million potential health interventions available to human beings, but no one sees any of those,” Tovar says. “Weight loss is the only solution we’re comfortable with.” Comedian and seminary dropout Bailey Wayne Hundl unpacks the United Methodist Church’s landmark decision to allow LGBTQ+ parishioners to become ordained ministers. “I never thought this change would come in my lifetime,” Hundl writes.  The loudest rap beef of the year was brimming with what music critic Julianne Escobedo Shepherd called “the expendability of women’s trauma.” In an in-depth analysis of the feud and fans’ responses to it, she peels back the layers to show us who really loses when two grown men decide to squabble in public. Tamara Costa had a partial molar pregnancy and needed an immediate abortion. But all she got was a sticky note with the phone number of a clinic 580 miles away from her home. As part of our United States of Abortion series, this film by Amy Elliott and story by Julianne Escobedo Shepherd show how one state’s severe laws punish families in terrifying health situations. In the wake of the 2024 election, reporter Megan Carpentier knew who she wanted to ask for advice: activists who have lived under (and resisted) authoritarian regimes around the world, from Hungary to Turkey.  And a Few of Our Favorite Podcast Episodes…“We Did Not Consent to Chaos” (UNDISTRACTED) Just 36 hours after Americans re-elected Donald Trump, Brittany Packnett Cunningham sat down with the people she most wanted to process this with: group chat regulars Dr. Brittney Cooper and Dr. David J. Johns. This is a conversation of righteous rage, deep disappointment, and total honesty. Worth a first and second listen. Rutgers Women’s Basketball & the Racist Radio Host (In Retrospect) In this award-winning two-part special, hosts Susie Banikarim and Jessica Bennett revisit the story of the 2007 Rutgers women’s basketball team—which made it to the finals of the NCAA championship, only to be met with racist vitriol from popular radio host Don Imus. But the Scarlet Knights pushed back—and one of them shares her personal reflections here. Love Abortion? Don’t Talk to the Cops! (The A-Files) All around the country, people have been arrested and criminalized for trying to access abortion care. In this episode, hosts Renee Bracey Sherman and Regina Mahone talk to Rafa Kidvai of the Repro Legal Defense Fund about that reality, and some surprising rules for responding to legal threats. Worth a re-listen, as cases like this mount. Debating Trans Rights? Maybe Talk to Trans People…with Laverne Cox (America, Who Hurt You?) Enjoy our work? We hope that you’ll consider supporting media made by and for women, girls, and nonbinary people, via The Meteor Fund. There’s one week left in our impact drive, and at this particular moment in time—when we know how important independent journalism is—we’d love to count you in. You can learn more about The Meteor Fund and donate here.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays. Ideas? Feedback? Requests? Tell us what you think at [email protected]

|

![]()

Let's Get Cozy!

|

Our comfort watches and reads to get you through the holidays

December 20, 2024 Happy holidays, Meteor readers, We hope you’re getting ready to wind down and spend time with your family or—if you’re super-lucky—with yourself. I didn’t realize until I had a child that the greatest gift is personal space, so I wish that for all of you this season. And if you’re looking for something engrossing for your me time, and need a break from the news-cycle nightmare that has been 2024, we have suggestions. Here, Meteor staffers and contributors share the pieces of media that have been their comfort touchstone throughout this year. The rules? Nothing too serious, and definitely no politics. We hope our binges and obsessions get you through the week! Wrapped in a blanket, Shannon Melero  A wacky network dramedy: Dr. Odyssey (VIA ABC) As the year progressed I required an increasingly smoother brain, and so it was a relief when Dr. Odyssey debuted in September on ABC. Essentially Grey's Anatomy meets The Love Boat, it was as risqué and madcap as an hourlong dramedy could achieve on a network, following a hot new cruise ship doctor (Joshua Jackson) trying to integrate with the existing medical team (Phillipa Soo, Sean Teale) and a stately captain (Don Johnson) who is always trying to fend off a rotating cast of suitors, from Shania Twain to Gina Gershon. Each voyage (and episode) is defined by a particular cruise theme—which opens the door for a slew of great Love Boat-esque guest stars, like Kate Berlant and Margaret Cho as dueling wellness influencers, and Bob the Drag Queen as entertainment for the Gay Week cruise (with John Stamos and Cheyenne Jackson as lovers who have opened up to a third). Dr. Odyssey sneaks in social commentary on topics like climate change, queer rights, and feminist agency amid tense operating room drama and steamy romance plotlines—there is more than one throuple brewing here—but it neither preaches nor condescends, and is the rare show on network television that doesn't glorify cops, ops, or killing. Soothing like a warm bath. —Julianne Escobedo Shepherd, contributing editor An offbeat, absorbing romance novel: Seven Days in June2024 was the year I got into romance novels, and my absolute favorite was Tia Williams’ Seven Days in June. The book follows Eva Mercy, whose erotica series has throngs of fans but no highbrow cache, and Shane Hall, an elusive author whose literary novels have gotten worldwide acclaim. After an explosive fling in high school, they reunite 15 years later, and—no surprise—the chemistry still sizzles. This is not one of the sunnier novels I read (it deals with some very, very dark teen angst and a Black woman’s generational trauma). But the sexual tension it offers, the level of investment I felt, its triumphant, multi-layered happy ending — all unparalleled. And beyond the steamy love story, I just adored Eva’s artist journey; I couldn’t wait for her to embark on the book she was destined to write. You’ll start Seven Days in June and not look up until you’re done. A great one to read in one-to-three sittings during the dead week of December. —Nona Willis Aronowitz, contributing editor The wonderful world of “cozy content”This year I learned about a special section of the internet devoted only to coziness. Think small farms and baby cows, rainy walks through Edinburgh, and knitwear. Lots of knitwear. As a knitter myself, I first fell into this rabbit hole looking for inspiration and now after months in the cozyverse I’ve sent about 3457934 DMs to my bestie Jenan (yes the Jenan) about the farm we’re starting with our children that will include donkeys, runner ducks, and alpacas for me only. Oh! And a shed for Bailey who sent in a formal request to live on the farm and teach the animals drag. —Shannon Melero, newsletter editor A messy (and historic) season of reality TV: Are You the One?God, I love bisexuals. If you haven’t seen season eight of MTV’s Are You the One?, let me break it down for you: 16 absurdly attractive singles get put in a house together, and they’re told that “relationship experts” (see: producers) have found their perfect match. If they can correctly identify the eight romantic pairings, they win a million dollars. And what makes season eight so special, you ask? For the first time in American reality television, everyone on cast is bi, pan, or otherwise sexually fluid. This season has all of my favorite things: Fighting. Fivesomes. Glitter. A Gemini who never shuts up. Not one, but two trans cast members! Genuinely, this season is one of my favorite pieces of trans representation across any media. Too often, I feel like when something contains trans characters, the people who wrote it ally a bit too close to the sun and depict us as these infallible deities. Season eight of Are You the One? shows that trans people can be insecure, cocky, manipulative, hammered, sexually desirable, emotionally unavailable—you know, human. Everyone on this show is so incredibly human and so incredibly queer. I cannot recommend it enough. —Bailey Wayne Hundl, copy editor A quiet tearjerker from the heartland: Somebody SomewhereI’ve spent the last few weeks bingeing Somebody Somewhere, an HBO series that tells the story of Sam—the magnetic, multitalented Bridget Everett—returning to her hometown in Kansas to care for her dying sister. The series starts a year after her sister has died, as Sam is struggling to rebuild her life. Somebody Somewhere is heartwarming and darkly funny, but also diverse in its view of the hopes and dreams of people outside of major cities. The location gives humanity to everyone from the church-going gay couple to the girlboss sister to the trans agriculture professor helping Sam’s dad figure out what to do with his land—a subtle reminder that exit polls and voting behavior don’t fully express the diversity of our experiences or connections. The show is feelgood, but you will likely cry during every episode. —Samhita Mukhopadhyay, collective member A blockbuster with heart (and Denzel): FlightThere is no reason whatsoever for this movie to bring me comfort, especially as someone who hates flying, but every time I rewatch the 2012 movie Flight, I feel better. Or maybe it’s just that it makes me feel at all. At first glance, Flight is a fairly formulaic Hollywood movie with a heroic redemption arc. What I see in it, though, is a trust-fall into near-Shakespearean depths of emotion that is less about redemption than humanity. Flight is about a cocky commercial airline pilot—Denzel Washington in an arresting performance that is somehow both sexy and pathetic—who pulls off a truly miraculous crash-landing in a plane that is hurtling toward the ground after a mechanical malfunction. Denzel is a great actor, full stop. As Captain Whip Whittaker, he is transcendent. The way he moves in and out of such a vast range of emotions, so that we can see the obvious ones (a satisfied swagger) and sense the not-so-obvious ones (the glassy-eyed grief over losing someone he didn’t love, but he knows was loved by others), is truly sublime. I watched it again last week, and was reminded of one quietly prophetic detail in Denzel’s performance: Early on in the film, Whip and his co-pilot are in the cockpit meeting for the first time, ahead of their fateful flight. “Ten turns in the three days. Off tomorrow,” Whip says, lingering on the end of “tomorrow,” with an understated smile. —Rebecca Carroll, editor-at-large  ENJOY MORE OF THE METEOR Thanks for reading the Saturday Send. Got this from a friend? Don’t forget to sign up for The Meteor’s flagship newsletter, sent on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Gisèle Pelicot Is Extraordinary

December 19, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, This Saturday marks the hibernal/winter solstice, making it the shortest day of the year. Not to get all woo-woo on y’all, but it is a great time to do a little gratitude practice and set your intentions for the upcoming season. So have a feast, take a nice hike, brew some mulled cider in your cauldron, and look inward.  In today’s newsletter, we consider the outcome of France’s horrifying rape case. Plus weekend reading, and if you haven’t checked it out already, another chance to fill out our reader survey! Bracing for the cold, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONGisèle Pelicot and the “unrecognized” victims: Today, the final verdicts came down in France’s Pelicot rape case. A brief and brutal synopsis: Over the course of ten years, Gisèle Pelicot was drugged and raped by a man she’d been married to for five decades, Dominique Pelicot, along with dozens of men whom he invited into their shared home to rape her while she was unconscious. He also filmed and took pictures of the assaults. In total, 51 men, Dominique included, were convicted of rape, attempted rape, or aggravated sexual assault, with prison sentences ranging from three to 20 years. Throughout all of this, Gisèle Pelicot has been vocal about having her story told and shifting the sense of shame from victims to perpetrators. She waived her right to anonymity and welcomed the press into the courtroom—both of which surprised many, given the horrific nature of the case. “By making this trial public from Sept. 2, I wanted for society to be able to take up the debates that followed,” Pelicot told the French press. “I have never regretted that decision.”  SUPPORTERS OUTSIDE OF THE COURTHOUSE WHERE THE TRIAL WAS HELD. ONE MAN HOLDS A SIGN THAT READS "THANK YOU FOR YOUR COURAGE GISÈLE PELICOT. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Those debates are numerous. What could justice look like in this situation? Will anything be done to address faulty policy and rape culture in (and outside) France? Could no one have intervened earlier, while the men were planning their attacks online or when Gisèle Pelicot went to various doctors for mysterious symptoms? These are crucial questions, and don’t stop mattering with this verdict; lawmakers and reporters should keep following them even once the hero at the center of this trial recedes into her well-deserved privacy. And there’s another question we cannot avoid revisiting: What kinds of victims deserve support? Ideally, the answer should be all victims. In her remarks after the verdict, Pelicot herself acknowledged this: “I think of the victims, unrecognized, whose stories often remain hidden,” she said. But many women who come forward are ignored, belittled, publicly mocked, blamed, and shamed back into silence. Pelicot has been rightly lauded as a hero for pursuing a criminal case against these men—but she, of course, ticks all the boxes of what we expect a “good woman” to be. She is a loving mother and grandmother, she’s older (a nice word the media uses to imply “not sexy or enticing to attackers”), and her trial had the golden egg of evidence: video recordings. We still live in a society that in its deepest heart believes that “good women” should not be raped and that those who are were probably asking for it. As Pelicot repeatedly reminded us: The only person to shame and blame for a rape, is the rapist—point blank period. AND:

WEEKEND READING 📚On a lifetime of silence: Earlier this year, Andrea Skinner, the daughter of late writer Alice Munro, revealed that she had been assaulted by Munro’s second husband—and that Munro knew. Skinner was forced to be silent for years. Why did her mother betray her? (New York Times Magazine) On more AI dangers: Tech companies pushing AI are also planning to build new gas power plants and pipelines to support the growing energy demands of AI. This is literally what they were asked not to do. (Heated) On criminalizing pregnancy: A prosecutor in Mississippi had been threatening pregnant drug users with 20-year sentences in the hope that it would force the mothers to get sober. He had no idea that the majority of these women had ended up in prison—until one woman, Brandy Moore, fought the charges against her. (The Marshall Project/Mississippi Today)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

How Safe are Abortion Providers in Blue States?

December 17, 2024 Darling Meteor readers, Way back in February, I started baking my own bread at home because the closest supermarket was charging $6 a boule, and that just felt criminal. I swore up, down, and around, however, that I would not do sourdough—too complicated. I’m sure you see where this is going. I’m now two days into making my own sourdough starter and this gloopy substance has become my fourth child (after my two dogs and one human). If any of you bread masters have guidance, step forward. In today’s newsletter, we’re untangling the complexities of an anti-abortion lawsuit out of Texas. Plus, some updates in the sports world. My starter runneth over, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONThe abortion battle to come: Last week, as you may have heard, the state of Texas filed a lawsuit against Margaret Daley Carpenter, M.D., a New York-based doctor and co-founder of the Abortion Coalition for Telemedicine, alleging that Dr. Carpenter had mailed abortion pills to a patient in Texas. Texas, of course, has a total abortion ban, but New York has a “shield law” meant to protect doctors who help out-of-state patients. Which law supersedes the other? Well, it’s complicated. The shield law protects providers from out-of-state criminal investigations or prosecution (among other things). But Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton is not pursuing a criminal case against Dr. Carpenter; instead, he wants to hit her with a $250,000 fine for practicing medicine without a Texas license and violating the state’s abortion ban. The New York shield law does address civil liability protection—specifically, it gives doctors a right to “protection against application of another state’s law in New York State court” and a “claw back lawsuit” option to reclaim any monetary damages incurred while fighting a charge brought for providing healthcare that is lawful in New York. But the suit is being filed in Texas, meaning that that first provision may not help Dr. Carpenter if this goes to trial. Texas’ legal code also states that a doctor cannot provide telehealth services to Texas residents without a license to practice medicine in the state. So, on the surface, it would seem that Texas has a slam dunk on its hands. Not entirely. Even if Texas wins the suit, experts don’t see a clear path for the state to enforce the judgment. But it’s not just about the money. There’s a wrinkle in this case that gives a hint of Paxton’s long game: Texas’s petition includes details about the man who impregnated the patient (we’ll call him John Doe). According to the petition, he only found out she was pregnant after he had driven her to the hospital to treat severe bleeding. Upon being told she had been nine weeks pregnant, John Doe “concluded” that the woman “intentionally withheld information from him regarding her pregnancy” and assumed she had done something to abort the pregnancy. He returned to the woman’s residence and found packaging for mifepristone and misoprostol. As law professor Mary Ziegler explains in Slate, this first-of-its-kind lawsuit may be trying to lay the groundwork for more cases involving male partners:

Are you following? Anti-abortion groups hope that men will sue over the “wrongful death” of fetuses they had a hand in creating. And in repeatedly referring to John Doe as the “biological father of the unborn child,” Texas may be trying to establish a legal precedent for those rights. To be clear, it’s not specified in the petition whether or not John Doe himself turned his partner in; he’s also not filing a wrongful death suit, and in the event Dr. Carpenter is made to pay a fine, John Doe would not be legally entitled to any of it. Still, a win here could signal to anti-abortion men that they now have the power to do something to gum up the works of telemedicine by telling Big Brother what their girlfriends are getting in the mail. And that will cost doctors, patients, and pregnant people in need a lot more than $250,000. AND:

IMAGE VIA THE DEBT COLLECTIVE INSTAGRAM (PHOTO BY JULIAN THOMAS)

LOCKER ROOM TALK 🏀 🏀 ⚽A fun safe space for our fellow women's sports fanatics

Hey! If you've read this far you must really like us. We really like you too! So much that we want to know what you think. Please consider filling out this survey to let us know how we can better support The Meteor community. FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

She Called Journalists "Monsters"and Liars

December 12, 2024 Hey there, Meteor readers, We are entering that special time of the year I like to call The Vortex, where time is meaningless and we are all just hauling ourselves across various finish lines. But before we fully get sucked in, I’ve got a special request. Please consider taking a few minutes to fill out this survey so we at The Meteor can better serve you. We want to continue building this community, and we can’t do that without you. Our suggestion box is fully open! In today’s newsletter, we turn to Trump’s latest hire. Plus, your weekend reading list. With appreciation, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONAnother one: Yes, we are talking about yet another questionable Trump appointee, but this one hits uncomfortably close to home for those of us who work in media. Yesterday, Donald Trump announced that he’d nominated former news anchor, election denier, and known hater of the free press Kari Lake to be the new head of Voice of America. A little refresher on VOA: It’s a federally funded international news provider that reaches more than 300 million people. Congress gives VOA $300 million a year, a sum Kari Lake would be responsible for managing despite her calls in 2022 to defund the media. The entire mission of VOA is to provide unbiased, fact-forward news and the organization even has a “firewall” rule which “prohibits interference by any U.S. government official in the objective, independent reporting of news.” This won’t be the first time a Trump loyalist has been given power over VOA. In 2020, Trump put one of his cronies, Michael Pack, in charge of the U.S. Agency for Global Media, which oversees VOA, and a judge found that he’d violated the First Amendment rights of VOA journalists and employees by attempting to censor and retaliate against those he deemed “insufficiently supportive of President Trump.” This time, we’ve got a woman who knowingly spreads disinformation and refers to journalists as “monsters,” a Republican-controlled Congress, and a news organization that relies on both journalists and Congress to function. What could possibly go wrong? Well, in the absolute worst-case scenario: You could end up with government-funded media that is loyal not to facts, but to one man’s agenda of revenge. That leaves the door open for worsening levels of misinformation that could border on propaganda. I hate to throw around that P word, but it’s gravely concerning that someone with such disdain for the truth could be given this much power over the telling of it. AND:

WEEKEND READING 📚On a growing movement: No one thought Puerto Rico’s Alliance coalition could win the election. But more than a hundred years of history points to exactly why their candidate, Juan Dalmau, came so close. (Truthout) On the other property brothers: Three brothers, two of whom were luxury real estate brokers, were arrested for their roles in a 14-year-long sex trafficking scheme. Their story is so heinous, it reads like an implausible horror film. (New York Times) On money and menopause: Millennial women are entering perimenopause in droves, and a new wave of health-adjacent companies are taking notice. In Retrospect co-host Jessica Bennett dives into what’s real and what’s a scam. (The Cut)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Could Trump End Birthright Citizenship?

December 10, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, My child recently learned the words to “Jingle Bells,” and while she cannot fully pronounce all of them, I’ve now heard that song more times than “All I Want for Christmas Is You.” Send earmuffs. In today’s newsletter, we take a look at the latest news on what’s ahead for migrants. Plus, actress and playwright Danai Gurira on the backlash to women’s rights on the African continent. Changing the station, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONA semblance of a plan: When the news broke that Donald Trump had won re-election, I reached out to my mentor, Julianne Escobedo Shepherd, and asked, “Did they tell you what time your group is getting deported? I’m in group C.” We laughed. After all, if the end is nigh, you cannot spend all your time suffering about suffering. But beneath the jokes, the memes, and the exhaustion, there is still a big question: Can Trump do all the things he wants to do? When it comes to immigration, it certainly seems like he’s going to try—and fast. Over the weekend in a “Meet the Press” interview, Trump reaffirmed his commitment to mass deportation, stating he would “absolutely” end birthright citizenship. “I don’t want to be breaking up families,” he said. (Really?) “So the only way you don’t break up the family is you keep them together and you have to send them all back, even kids who are here legally.” Because of the 14th Amendment—which does a few things including granting citizenship to anyone born on U.S. soil—Trump cannot make good on his threat by himself, but that doesn’t mean it’s an impossibility. As reporter Isabela Dias explains in Mother Jones, Trump and his allies could “resort to the far-fetched claim that large migrant flows to the US-Mexico border constitute an ‘invasion’ of the United States and, therefore, the children of unauthorized immigrants should be excluded from the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of birthright citizenship.” That idea might seem implausible, especially when even Republicans are divided on mass deportation (as demonstrated by today’s Senate Judiciary Committee hearings). But we are living in implausible times. If the president thinks the 14th Amendment is up for debate—and let me remind you that the amendment’s equal protection clause is literally being debated before SCOTUS—there’s no telling how far he’ll go to get his way. And when the “them” he’s targeting starts to look like everyone, what will be the line in the sand? AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Revisiting the Timeless Wisdom of Black Women Writers

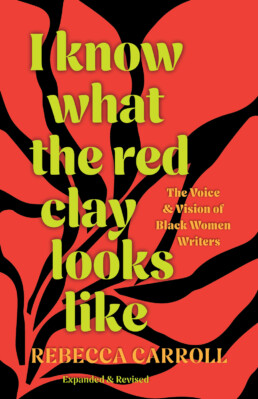

Rebecca Carroll’s 1994 anthology is re-released for a new generation.

In the summer of 1992, three books by Black women writers–Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and Terry McMillan—made the New York Times bestseller list at the same time. I knew it had to be a first (it was), and to me, a recent college graduate and aspiring writer, it felt like a divine intervention. Two years later, inspired by that moment, I published a collection of interviews called I Know What the Red Clay Looks Like: The Voice and Vision of Black Women Writers. The book featured established writers like Nikki Giovanni and Rita Dove, as well as then-emerging voices like Lorene Cary and Tina McElroy Ansa.

Thirty years later, Red Clay is being re-released. And after an election that could have given us the first Black woman president but didn’t, this collection of intergenerational Black women and nonbinary voices feels like a necessary balm. In the new edition, I invited a younger writer to re-introduce the work of each original writer featured. In the excerpt below, New York Times Magazine staff writer J. Wortham explains what poet June Jordan’s work means to them, and to our world right now. And then, June Jordan speaks for herself.

—Rebecca Carroll

J. Wortham on June Jordan: “It is June Jordan’s time on the world clock again.”

June Jordan was an author, a professor, an activist, a poet, a parent. She was also a horologist. What I mean by that is she kept time. And time could be kept by her. When she wrote “Like a lot of Black women, I have always had to invent the power my freedom requires” in her 1985 essay collection, On Call, that was her way of calling for solidarity with the uprising in Nicaragua and drawing throughlines between the communities there and the American South, between her West Indian upbringing and our own ongoing liberation struggles.

The first time I read those lines, I gasped. I was gifted a collection of her prolific writings (including the essay with that searing line) called Some of Us Did Not Die and marveled at the breadth of her cultural criticism. She vivisected pop culture, Clarence Thomas, South African apartheid, motherhood, the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr., with equal ease. She wrote toward the future while keeping the present accountable, even when it was considered unfavorable. June identified as a bisexual and often wrote about the Palestinian freedom struggle, including the oft-Instagrammed lines “I was born a Black woman and now I am become a Palestinian.”

…Her legacy has been dimmer than what she righteously deserves, despite being as firm a literary figure as Alice Walker or Toni Morrison, in community with Ralph Ellison and Malcolm X, and calling Fannie Lou Hamer a friend. But it is June Jordan’s time on the world clock again. “I mean to be fully and freely all that I am,” she wrote in a keynote speech delivered at Stanford University in April 1991. Even now, she is.

June Jordan on clarity: “I don’t even like to use the word racist”

I’m not concerned about missing anybody with my writing. I think that there is a racist, patronizing point of view around understanding certain ideas where black folks are concerned that I do not embrace. Most everything I write, I test out. Big audiences. Live. And that’s poetry as well as essays. So, it’s not too hypothetical to me whether it’s gonna hit or not. If it hits, I know. If it doesn’t hit, I know….

…A pivotal event for me as a writer and a poet happened during the sixties. It was a great big poetry reading down in Jackson, Mississippi. It was all black women poets—Sonia Sanchez, Audre Lorde, Mari Evans, I mean, you know, everybody at that time. It was held in a huge auditorium. I just thought I was the baaaadest poet in the world with my baaaad Brooklyn self. I got down there and was blown away. The place was packed, and folks was all dressed up, families and children and deacons. And all my poetry had profanity in it, and I was like, “Oh shit, I can’t read anything!” And Sonia said, “See? I told you so!” I mean, it was like church. Everybody was on time—in black Mississippi folks was on time! And I would never have presumed to imagine that being a poet merited that sort of respect. And trust. At that moment, I realized that as a black writer, people were looking to us/to me for vision, leadership, and most of all, people were looking to us/to me for The Word.

I think as long as you try to be clear, and I always try to be clear, people will get it. I may have a word in my writing that somebody may not know, but that’s just a word, and that’s it. I think mostly my language is extremely straightforward, and I have worked on it quite a bit. It is not academic. And it is not common. You’ll never see the word feminist in my work, or patriarchal, or any of that—I just don’t use words like that. I’m not writing for the academy. I don’t give a shit about the academy. I’m writing for people who read. Mainly I try to reach college students, which is a huge, heterogeneous, and important audience to reach.

Academic language includes a lot of stupid words. I don’t even like to use the word racist. If I do use it, I have to really try and use it in a way that is still fresh, so it still hits and stings, so that people understand that “I’m here to kill you because of this.” You know what I mean? I’m not saying, “Well that was a racist incident,” no, I don’t mean it was a racist incident, no, I mean, “I’m gonna kill you cause that was racist!” How you rest that word in any usage, to give it the power that it originally had, is important. For example, in the context of Rodney King, some people call that a racist episode, which makes the word racist sound tepid—you know, it was pleasant, unpleasant, racist, casual, and so on. All those words sound the same. I try to use words, whether in prose or poetry, that people can understand, that make them feel in an intense way. I’m a writer, that’s what I do.

Want to read more? Three June Jordan works to start with:

An essay: The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America

A young-adult novel (her only): His Own Where

And, of course, poetry: The Essential June Jordan

Rebecca Carroll is a writer, cultural critic, and podcast creator/host. Her writing has been published widely, and she is the author of several books, including her recent memoir, Surviving the White Gaze. Rebecca is Editor at Large for The Meteor.

Iran Temporarily Releases Narges Mohammadi

December 5, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, It’s the least wonderful time of the year—and by that, of course, I mean Spotify Wrapped season. We get it, you’ve got great* taste in music. (*Editor’s note: This does not apply to all of you.) In today’s newsletter, we stand in awe of Narges Mohammadi and catch up with the Court’s big day yesterday. Plus, your weekend reading list. Wrap literally anything else, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONNobel laureate and Iranian human rights activist Narges Mohammadi has been given a three-week medical release from prison in Tehran. Mohammadi has been in and out of prison for decades and, since 2021, has been serving a 13-year sentence on charges of “spreading anti-state propaganda” for her work in Iran’s women’s rights movement. As she was being wheeled out of an ambulance on a stretcher after her release, without the required head covering, Mohammadi shouted the movement’s slogan: “Woman, Life, Freedom!” Mohammadi has suffered several health issues during her imprisonment, including multiple heart attacks and, most recently, an emergency surgery to remove a cancerous tumor. After her leave, the state expects her to continue her imprisonment in Evin Prison. Mohammadi’s lawyers and the international community all believe that her continued imprisonment is inhumane and a violation of Mohammadi’s rights. MOHAMMADI AFTER HER RELEASE HOLDING A PHOTO OF MAHSA AMINI. WRITTEN ON HER HAND IS "END GENDER APARTHEID" IN FARSI. (IMAGE VIA INSTAGRAM) Despite the severe crackdowns on public gatherings since the Mahsa Amini protests shook the nation two years ago, Iranian women have continued the fight against their theocratic government, which has in turn intensified punishments against them. Iran's Hijab and Chastity bill—which will punish both women and men for “improper dress” by issuing fines, blocking country exit permits, and, in some extreme cases, imprisonment—will go into effect next week. As Mohammadi recovers at home and continues to speak out for Iranian women, we are reminded of the words she wrote while still imprisoned: “Victory is not easy, but it is certain.” AND:

WEEKEND READING 📚On challenging the norm: For the last 50 years, one feminist magazine you may have never heard of has been pushing back on Mormon tradition. And it’s written by Mormon feminists. (High Country News) On asking and telling: Trump’s return to office has stirred up concerns about the resurgence of anti-LGBTQ+ “witch hunts” in the military. (The War Horse) On paying up for postpartum care: Retreats for new moms, which have long been the norm in parts of Europe and Asia, are popping up in the U.S. But at an astonishing $1,000 per night, are moms and babies getting what they’re paying for? (The Cut) On your speakers: The latest episode of America, Who Hurt You? dives into the lesser-known history of Muslims in America. (Apple podcasts)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

This Law Could Run for President. It's That Bad.

December 3, 2024 Greetings, Meteor readers, So as your inbox has probably told you quite a few times today, it’s Giving Tuesday. We promise not to bombard you, but should you be in a particularly giving mood today, we hope you will consider supporting our nonprofit project The Meteor Fund. It hosts regular community events on everything from abortion access to climate change, and supports The Meteor’s journalism, including projects like United States of Abortion and The A Files. We know you have many places to give. We also know that in a time of disinformation, it’s never been more important to support independent media that unapologetically centers the interests of all women. In today’s newsletter, we take a look at the transgender rights case making its way to the Supreme Court. Plus, we’re reclaiming locker room talk. Grateful for you all, The Meteor Team  WHAT'S GOING ONA high-stakes SCOTUS case: ACLU attorney Chase Strangio will make history this week as the first openly transgender person to argue before the Supreme Court. The case at hand? United States v. Skrmetti, which will broach the question of whether or not Tennessee’s anti-trans law is a violation of the 14th Amendment. Let’s put that in plain speak for my non-Suits watchers out there. Tennessee SB1 prohibits any medical personnel in the state from providing care that enables “a minor to identify with, or live as, a purported identity inconsistent with the minor’s sex.” Translation: It bans any and all gender-affirming care specifically for transgender minors. It does not however stop, say, a cis-gendered teenage girl from receiving estrogen for any reason because, that form of gender-affirming care is not “inconsistent” with the patient’s sex assigned at birth. This bill is so loudly and staunchly anti-trans, it could run for president and probably win. Lawyers representing Tennessee are citing the court’s 2022 Dobbs decision, which eliminated the right to legal abortion, as grounds for upholding SB1, saying that it is not discriminatory but merely “an even-handed regulation of medical procedure.” The use of Dobbs as precedent is part of what makes bringing this case to a wildly conservative court such a gamble: The way they rationalize it, Dobbs didn’t discriminate based on sex; it merely regulated how abortions can be administered in this country. 🙄 The ACLU’s argument, on the other hand, is more attuned to the reality of what these laws are trying to achieve: the eradication of transgender people. “Laws like Tennessee’s are not benign regulations of medical care,” Strangio said in a statement. “They are discriminatory efforts to exclude transgender people from the protections of the Constitution.” Or, as Ria Tabacco Mar, director of the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project, put it: “There is no ‘transgender’ exception to the U.S. Constitution.” There’s a lot riding on whether the justices agree. If SB1 is allowed to stand uncontested, the decision would embolden more states to pass more anti-trans legislation. (Twenty-six have banned gender-affirming care already.) If, on the other hand, SCOTUS rules favorably, the outcome could grind anti-trans legislation to a halt nationwide, and establish important limits on how state law can dictate an individual’s health care. There are, of course, many hitches in this giddyup, the largest one being the “U.S.” in “U.S. vs. Skrmetti.” Right now the Biden administration is the “U.S.”—Biden’s DOJ brought the lawsuit along with three trans minors and their families. But when he leaves office in January, the Trump administration might switch to supporting Tennessee. Should that happen, experts say there is a possibility that SCOTUS could request a new hearing to decide whether it should accept the ACLU’s petition at all. Regardless, Strangio and the ACLU are focused on the real people at the heart of the suit. “This is Tennessee displacing the loving, reasoned, painstaking decisions of parents who are trying to do right by their children,” Strangio explained to Dahlia Lithwick on the Amicus podcast. “Children who were in anguish, and are now doing better, because of the health care Tennessee now bans.” AND:

PROTESTORS OUTSIDE OF THE INC-5 CONFERENCE IN BUSAN, SOUTH KOREA. (VIA UNEP)

LOCKER ROOM TALK 🏀 🏉 🏃♀️A fun safe space for our fellow women's sports fanatics

SCREENSHOT OF MY BESTIE VIA INSTAGRAM  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

How to Fight Autocracy, From the Activists Who've Done It

BY MEGAN CARPENTIER

When Donald Trump vowed in December 2023 to be a dictator “on day one,” his aides later clarified that he “was simply trying to trigger the left and the media.” Nonetheless, exit polls showed that half of voters “said they were ‘very concerned’ that another Trump presidency would bring the U.S. closer to authoritarianism,” even though some voted for him anyway.

In the weeks since the election, democracy advocates have raised the alarm about the possibility that, after nearly 250 years, the American system of constitutional governance may be compromised. Many people are worried that Trump will try to hold onto office illegally in 2029; he’s told voters, special interest groups, and House Republicans he’s considering an unconstitutional third term. Critics note his hostility to the free press, his early demands that all his appointments skip confirmation hearings (to which Senate Republicans currently seem unlikely to acquiesce), and his promises to use the Department of Justice to go after perceived political enemies.

Looking at history, the worry that Trump could destroy some of the fundamental guarantees of democracy are not without precedent: All around the world, voters in democratic countries have elected leaders who then undermined the very systems that brought them into power—including the 20th century’s most infamous authoritarian, Adolf Hitler.

How does that happen? What lessons can—and should—Americans learn from other countries which have recent experience with authoritarian rule? Given that scholars have repeatedly found that authoritarian countries are worse for women’s equality, this guidance feels more needed than ever.

So we asked the advice of a few activists from across the globe who know what it’s like when authoritarianism comes your way.

“People exchange their freedoms without actually realizing the consequences for everybody.”

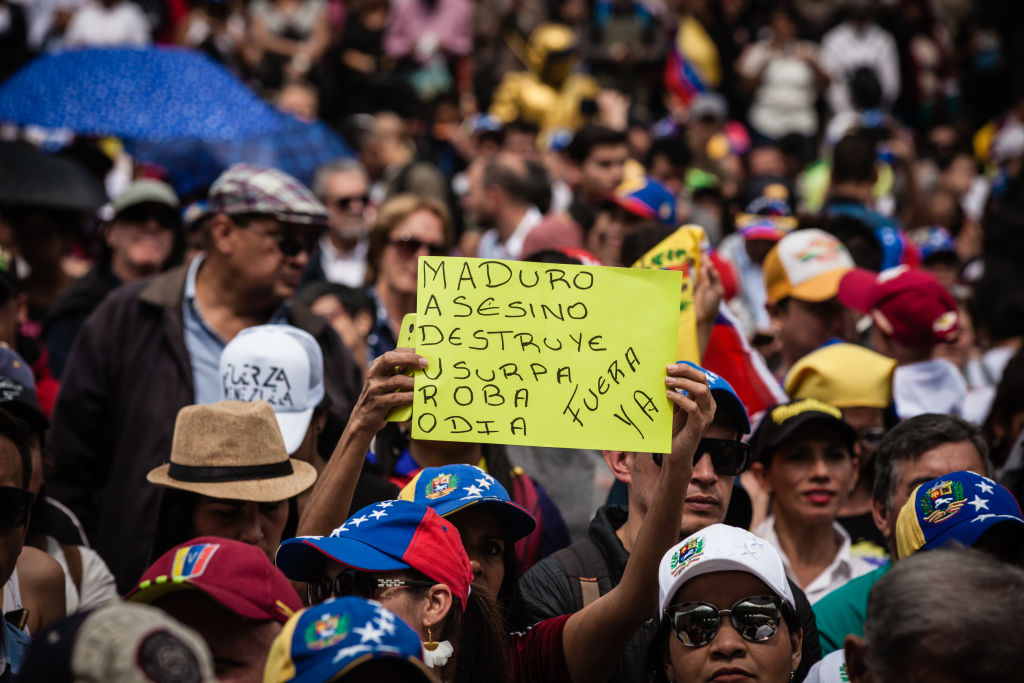

—Génesis Dávila, founder and president of Defiende Venezuela. In Venezuela, current president Nicolás Maduro—handpicked successor of autocrat Hugo Chávez—presides over an authoritarian regime, and recently declared victory in an election he is accused of rigging.

“Something that we couldn't learn on time in Venezuela is that polarization is a poison for the entire society. When we had Chávez and then Maduro in power, they targeted the opposition as enemies and, when they did that, then the opposition also targeted them and their supporters as enemies. The opposition would say Chávez supporters were not smart people, that their values were against the country’s.

“It worked in favor of Chávez and Maduro. I would not want to support someone who is attacking me. I would not want to support someone who believes that I'm not smart. I would not want to support someone who thinks that my values are wrong and their values are right.

“Chávez came to power with the support of the people [but]...he took control of the judiciary and the legislative branch. He announced limitations on freedom of speech; he announced the reform of the Constitution. At the end, he was pretty much able to do whatever he wanted without any resistance. He had 100 percent impunity. [And under Chávez and then Maduro], we moved from being a strong democracy with a strong economy to one of the poorest countries in our region.

“We cannot perceive our fellow citizens as our enemies. We have different perspectives, different values, but we must be willing to find common ground. We need to create bridges, and we need to help them to walk to the other side—but we cannot push them, and we cannot attack them.”

“You can't protect democracy if you're not offering a really inclusive social and economic agenda.”

—Gábor Scheiring, Assistant Professor of Comparative Politics at Georgetown University in Qatar and a former member of the National Assembly in Hungary, where Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has ushered in what the European Parliament has denounced as an “electoral autocracy.”

“I'm a huge supporter of liberal democracy and institutions, but you can't really protect those cherished liberal institutions by just talking about how important it is to have a constitutional court and how important media pluralism is. The overwhelming majority of people don't really think in these terms. They are concerned about inflation and real wages and unemployment and inequality, and that's where you need credibility if you're trying to represent those masses.

“So, the old elitist ways of doing progressive politics will not help you. You can’t just continue talking about the values of democracy, as opposed to talking about issues that matter to people. That's just not working. It's not helpful.

“You need to convey a message of significant change, and do that in a credible way….Beyond that, in the U.S., if you have any friends who have a lot of money and can use it to support significant, large, liberally-oriented media outlets, I think that's super important….If we’re frank, conservative billionaires, they invest in conservative media, even if it doesn't pay out immediately. Liberal billionaires in Hungary, they just did not really care to help sustain non-right-wing media. And I think that's a huge, huge problem.”

“As long as people remain organized, there is hope.”

—Halil Yenigun, Associate Director, Stanford University’s Sohaib and Sara Abbasii Program in Islamic Studies, and former professor in Turkey, where President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s time in office has generally been characterized as a movement away from democracy.

“There are a few basic differences between the Turkish government and the American one today that favor American democracy.

“One is that the U.S. judiciary is still a lot more independent than Turkey’s ever was. So even when Trump transgresses certain limits, some conservative justices still stand up against him, like they did with the election fraud claims. The second one is that the U.S. is a federal government, and federalism still creates some kind of counter-force to a centralized, authoritarian government. Don’t take the institutions for granted. Don't take checks and balances for granted.

“Another institutional mechanism [in both the U.S. and Turkey] is the opposition party organization. Turkey had a multiparty democracy before President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was first elected, and, even after, the opposition party organizations did not give up….Each and every election, they just continued fighting back.

“Even though in Turkey, we did not have the same kind of strong civil society as in the U.S.—we don’t have as many NGOs—civil society proved to be a very important channel for people to remain organized. There are still these openings to express opposition to the regime, like Pride Day and especially the women's movement and the annual Women’s March. [That] movement might seem as though it is about a single issue like women's rights, but it serves as a channel for people to vent their resentment against repression.

“These pockets of resistance are very important, I think, to prove that people can still fight back.”

“We realized that we needed to inform people what human rights are.”

—Cristina Palabay, secretary general of the human-rights organization Karapatan in the Philippines, where former president Rodrigo Duterte’s term from 2016 to 2022 was characterized by extrajudicial killings, human rights abuses, efforts to change the country’s constitution, and more.

“How Duterte spoke about human rights was, ‘OK drug addicts are not humans, They are animals.’ This was the dehumanization in which the administration was engaging.

“We realized that we needed to go back to basics, to inform people what human rights are. We had to explain that human rights are more than what is written in the Constitution—more than just legal rights. Human rights are the right to a dignified life, the right to food, the right to just wages, the right to live at all. People can have a basic understanding of human rights when it is spoken about in a way that is easily understandable to them.

“But, as we were educating people, the situation kept getting worse. When kids started to get killed in the drug war, that's when people started to think, OK, so, this is not just about drug addicts. And then, of course, he went after the human rights defenders and he took a militarist approach during the pandemic.

“Based on this education, people started to question the dehumanization of people. And that’s when we realized that Duterte’s propaganda was not as widespread a success.

“It became a defining moment for many of us—civil society, social movements, journalists, even artists—to all come together to mount some kind of pushback, including online. And we did that.”

Megan Carpentier is a freelance writer and editor. She is an alumna of NBC News, The Guardian, Talking Points Memo, and Jezebel, among others, and her byline has appeared in Foreign Policy, Ms. Magazine, Rolling Stone, Esquire, Glamour, and The New Republic.