You Can Live Here, Until You Can't

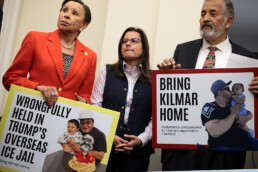

April 10, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, I never want to hear, read, or write about tariffs ever again. The whiplash is exhausting. In today’s newsletter, we connect the dots on the administration’s attacks against immigrants. Plus, the SAVE Act shows signs of life. He’s coming for our cheese, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONWho gets to live here?: “I don’t understand why you’re so worried—you can’t be deported,” is a statement I’ve heard from several people since I started covering Trump’s mass deportation plans—plans which have seen more than 300 student visas revoked, about a dozen legal U.S. residents imprisoned, at least seven U.S. citizens detained (one apparently for legally representing a student protester), and one Maryland man deported. In the city where I live, ICE has carried out raids that have led to veterans being arrested without cause. And now, just two days ago, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt confirmed that the Trump administration is looking into policies that would allow for the deportation of incarcerated U.S. citizens. This would be, of course, utterly illegal because of the Eighth Amendment; as one expert told Truthout, “There’s not even a hint of a possible way to do it under any circumstances whatsoever.”  MEMBERS OF THE HISPANIC CAUCUS HOLD UP IMAGES OF KILMAR ABREGO GARCIA, THE MARYLAND WHO WAS "MISTAKENLY" DEPORTED TO EL SALVADOR. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) But it was also illegal to deny due process, until it wasn’t. It was illegal to detain someone without a warrant and probable cause, until it wasn’t. There’s one thing you can say about the Trump administration: They’re resourceful. Whether by hook, crook, executive order, skirting the courts, or resurrecting wartime laws, this administration has proven it won’t be deterred by the legal process. Ostensibly, the judicial system should be able to protect the vulnerable—and some have been spared—but it simply isn’t happening fast enough for those currently sitting behind bars in Louisiana, Goshen, New York City, and El Salvador. In other words, this fear is not baseless. What I see in front of me is not a collection of disconnected arrests and deportations; I see the slow, carefully curated removal of people of color—especially outspoken ones—from the United States. People like my late father and my brothers who would meet Trump’s stated criteria for detention (criteria I will not specify because I’m not a snitch). People like my best friend, a woman well-known for speaking up for Palestinians on social media. People like my neighbors, many of whom are immigrants. What good is anyone’s perceived safety if the people who make living here worth it aren’t safe as well? The administration is making clear that it wants to paint protestors and people of color as an enemy—they’re literally deporting people under the Alien Enemies Act—but you’re the one who gets to decide who your enemies are and it’s not the protestor, or the Venezuelan dad, or the troubled teen. It’s probably just Deb, in accounting. AND:

I AM SO GLAD MY HUSBAND IS NOT A LEBRON FAN BECAUSE I'M NOT SPENDING $75 ON THIS. LOOKS GREAT THOUGH. (VIA MATTELL)

DOLORES HUERTA AND PRESIDENT OF THE AMAZON LABOR UNION CHRISTIAN SMALLS AT THE METEOR'S 22 FOR '22: VISIONS FOR A FEMINIST FUTURE. (VIA GETTY)  WEEKEND READING 📚On girls’ rights: School-aged girls across East Africa are being kicked out of school after forced pregnancy tests. (Teen Vogue) On being untethered: What would a woman’s life look like disconnected from the relationships that so often define it? Novelists are trying to imagine. (The Atlantic) On co-opting feminism: How the French far-right uses the language of women’s rights to demonize immigrants. (The Baffler)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Death By 10,000 Layoffs

April 8, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, Congratulations to newly crowned NCAA champions the Florida Gators and UConn Huskies. But more importantly, congratulations to me for winning my first bracket pool ever! It only took three years 🥴. In today’s newsletter, we look at the woman-specific impact of layoffs at the Department of Health and Human Services. Plus, we’re all still thinking about The White Lotus. Shannon Melero 🏆  WHAT'S GOING ONDeath by (ten) thousand layoffs: Last week the Trump administration decimated the Department of Health and Human Services; in the words of one former employee, “shitshow is an understatement.” As a result, the organizations housed under HHS—the Center for Disease Control, National Institutes of Health, Food and Drug Administration, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid— lost 10,000 staff members, effectively shuttering a number of departments. But not just any departments; the cuts will roll back decades of hard-won progress on women’s health research. Just take a look at what we’ve lost: Most of the CDC’s Division of Reproductive Health was laid off, including the team responsible for updating contraception guidelines and groups researching IVF and fertility clinics’ success rates (despite Trump’s promises to make the procedure more accessible). Three of the four branches of the Division of Violence Prevention were also eliminated. The division, established three decades ago, was crucial to framing violence as a public health problem, and yet last week, on the first day of Sexual Assault Awareness Month, all of the staff working on intimate partner violence prevention and sexual assault prevention programs were dismissed. The administration also fired all of the CDC scientists researching drug-resistant STIs. As is usually the case, these cuts will disproportionately impact Black, Latine, and lower-income women. The entire team working on the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, a project started in 1987 to reduce infant morbidity and mortality by offering maternal health guidance through the entire birth process, was laid off last week. “Black women in America are three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women,” one expert told Rolling Stone, and “we know this in large part because of the data collected and analyzed by the CDC.” And the timing of the system’s shutdown couldn’t be worse, a public health professor explained to Mother Jones: It “jeopardizes women and infants’ health at a time when maternal mortality rates in the US have been rising and access to maternity care is increasingly difficult.” So what happens next and how can you help? Lawyers contend that many of the layoffs are on “shaky legal ground”; some state attorneys general have sued to block them. If your state hasn’t joined the lawsuit, file a complaint with your AG’s office online and ask them to fight back against these layoffs. If there is a local domestic violence shelter or rape crisis center in your area, it’s a great time to call them and ask exactly what they need. The government may not care, but we still can. AND:

MY CHILD'S FAVORITE COUPLE, MS. RACHEL AND HER HUSBAND MR. ARON. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Lessons from an epic 2013 filibuster

April 3, 2025 Dearest Meteor readers, I gotta say I’m looking forward to this weekend—and not only because there’s a Hands Off! protest a mere five-minute drive from my upstate New York home, which NEVER happens (find the closest event to you here). A friend is also throwing a White Lotus finale party, and I could use a party in my life.  Today, we look back at our favorite filibuster in the wake of Cory Booker’s marathon speech. Plus, where American women have the most (and least) power, and your weekend reading. With love and tsunamis, Nona Willis Aronowitz  WHAT'S GOING ONThe art of the filibuster: Sen. Cory Booker broke a Senate record earlier this week when he spoke on the floor for more than 25 hours to protest the actions of the Trump administration. Without taking a bathroom break or even sitting down, he addressed an array of issues, from Elon Musk’s government takeover to tax cuts for the rich. Underneath the livestreams on YouTube and TikTok, encouraging comments whizzed by at breakneck speed. Was it political theater, a stunt? Absolutely (and maybe that’s a good thing). Could it actually do something? Depends on how you look at it. Unlike a traditional filibuster, Booker wasn’t trying to hold up particular legislation; rather, he was there, as he put it, “disrupting the normal business of the United States Senate.” And even true filibusters don’t have a great record of halting the laws they’re protesting. Sen. Strom Thurmond, a segregationist who held the previous record of longest speech in the Senate by filibustering the Civil Rights Act in 1957, failed to block the historic legislation. “I’m here despite his speech,” Booker noted. The more recent filibusters of Sen. Chris Murphy and Sen. Ted Cruz didn’t kill any laws, either. What highly publicized marathon speeches like filibusters can do, however, is drum up energy, draw focus, and create symbols that inspire tangible action. Take the case of Wendy Davis, the first filibuster I personally remember watching. In 2013, the then-Texas State Senator held an 11-hour-long filibuster to block SB5, an omnibus abortion bill that, among other restrictions, banned abortion after 20 weeks in the state and required that abortion providers have admitting privileges to nearby hospitals. (Sounds quaint now, but these laws really were canaries in the coal mines.) Flanked by abortion rights supporters who one Republican called an “unruly mob,” Davis and the Democrats managed to run out the clock past midnight, preventing SB5 from being signed into law.  WENDY DAVIS IN THE EARLY HOURS OF HER 2013 FILIBUSTER. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)It was an electric moment in politics and feminism. Davis—a telegenic lawmaker with a powerful backstory who, the internet noted at the time, bore a striking resemblance to Friday Night Lights’ Tami Taylor—became an instant icon of reproductive freedom. Even the pink running shoes she wore during her filibuster got famous. For a while, Davis was the toast of national Democrats, not to mention a then-thriving feminist blogosphere. We all know how this story ends: Wendy Davis’ unforgettable stand did not stop the anti-abortion movement. The Texas abortion bill eventually passed in the form of HB2—and although the Supreme Court struck down that law in 2016, it would later overturn the constitutional right to abortion in 2022. For her part, Davis ran for governor in 2014 and lost badly. And yet, Davis’ filibuster made its mark. It inspired women to run for office, get involved in politics in her state, and start new abortion funds. From all the way in New York, I became aware of red-state movements to protect abortion in a way I wasn’t before. Meanwhile, I am no fan of Booker’s, but even I have to admit that his speech lifted my mood. I was impressed by his stamina; I spent more time than I’d like to admit looking into the, um, physiology of it all. Will those rah-rah comments under the livestreams translate into action? Into mutual aid, into more public refusals, into other members of Congress disrupting Trump’s plans, into some of us running to replace them if they don’t? I sure hope so. AND:

AN ACTIVIST MAKES THE VULVA SYMBOL DURING THE 2023 PROTESTS IN TURIN. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

Three Questions About…PowerWhere women have the most (and least) of it, from a new study by Dr. C. Nicole MasonBY SHANNON MELERO  Last month, the new initiative Future Forward Women published its first U.S. Women’s Power and Influence Index, a state-by-state breakdown of where women have the most and least overall power—as measured by education, economic status, political inclusion, and a dozen more key indicators. The report found that Alabama is the lowest-ranking state, with women wielding the least overall power there, and the highest-ranking isn’t even a state—it’s the District of Columbia. We asked Future Forward Women president Dr. C. Nicole Mason three questions about what it all means. First, how did you define“power” for this research?For me, “power” is the ability to influence or direct the actions of a group or society toward a specific desired outcome. I started with the premise that although women are 50 percent of the U.S. population, we are still the most likely to live in poverty, to experience sexual harassment or gender-based violence, and to live in states where we don’t have complete bodily autonomy. Politically, we hold less than a third of elected offices. I wanted to understand why—and the why for me was power; we don’t have enough of it. Or at least not enough to…pass common-sense laws and policies that would make our lives better. In our society, it’s not okay for women to say they want power—but that’s what we need, especially right now. Which finding surprised you the most?The states of Florida and Texas ranked third and fourth in terms of women's political power and influence [but ranked 25th and 45th, respectively, in terms of the overall power women wield]. What we observed is that even though both Texas and Florida have high numbers of women in their state legislatures, Congress, and executive leadership positions, that’s not enough. Yes, we want women in political office, but these women and men must support policies favorable to women and families. Washington, DC, ranked number one in the index because DC has the highest median earnings for women in the nation, along with high levels of education. However, across all states, without exception, women of color are not doing as well as their white counterparts. For example, in the District of Columbia, the poverty rates for Black women are notably high. There is not a single state where women of color are faring [just as] well or better than other women. What are the most important takeaways from the report?We need to decide that it’s not okay for state borders to determine the rights that women have or don’t have in this country. It wasn’t okay 400 years ago and is not okay now. For new models and inspiration, we should look to other countries’ universal childcare, paid sick and family leave, reproductive freedom — [and ones] that have faced similar threats to democracy and the erosion of rights. We should also go to the states where women have the least power and influence. Not going to those states will cost us because they become the testing ground for bad policies. Living in a high-power state will not protect you. We are in this together. Lastly, we need to have radical imaginations, dream big, and say what we want out loud to inspire others to join us. We need everyone, in their own way, to help us win big.  WEEKEND READING 📚On history’s “quiet moments”: Presidential historian Alexis Coe looks back at Lyndon B. Johnson’s hire of Geri Whittington, the first Black woman to be a president’s secretary and a “testament to his administration's complex, often contradictory, yet unwavering commitment to racial equality.” (Harper’s Bazaar) On sex and death: A tantalizing profile by thee Rachel Handler of Michelle Williams, who stars in a new FX show, Dying for Sex, about a terminal cancer patient’s last-ditch sexual odyssey. (Vulture) On grief and care: Years ago, Houston-based Black midwife DeShaun Desrosiers experienced a traumatic birth. She’s now on a mission to train doulas of color in her community. (Houston Landing)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Good abortion news out of...Alabama?

April 1, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, The women’s Final Four is set, and thankfully for my bracket, UConn is still in it along with UCLA, Texas, and South Carolina. As much as I love Dawn Staley, I need anyone but South Carolina to win as I refuse to lose to my own husband in our bracket battle.  In today’s newsletter, we celebrate a win for abortion in Alabama. Plus, one very expensive election and an answer to whether or not your basketball tattoo can get you arrested (it can). Cheering for Paige, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONSometimes we win: On Monday, a federal judge in Alabama ruled that the state could not prosecute people for obtaining abortions in states where the procedure is legal, writing in his decision that “Alabama’s criminal jurisdiction does not reach beyond its borders.” (Someone tell that to Ken Paxton.) The judge also wrote that going after people or organizations who help others get abortions “would violate both the First Amendment and the right to travel.” The ruling comes in response to a 2023 lawsuit filed by Yellowhammer Fund, the state’s only abortion fund, along with West Alabama Women’s Center (WAWC) and Huntsville OB/GYN Dr. Yashica Robinson against the state’s attorney general Steve Marshall, who had publicly threatened to criminalize anyone aiding out-of-state abortions under a criminal conspiracy law from 1896. Even just those threats had been having real-world consequences in Alabama, where abortion is illegal in all instances with very, very few exceptions. Robin Marty, the director of operations for WAWC, told The Meteor that even after Roe was overturned, people came to the center seeking care—often unaware that abortion had become illegal. But because of Marshall’s threats to enforce anti-conspiracy laws, Marty says her staff was severely hindered from offering patients guidance on how to get an abortion, despite no new legislation being on the books. “We had to say ‘I can't help you,’” Marty tells The Meteor. “Because any information that we provided would then be potentially considered to be the beginning of that so-called criminal conspiracy.” If that kind of cruelty on top of cruelty—in which the state mistreats patients and bars anyone from helping them—sounds familiar, that’s because a number of other anti-abortion states are also manipulating existing racketeering and conspiracy laws to make it nearly impossible to access abortion care. Idaho and Tennessee have already codified so-called “abortion trafficking” laws, making it a felony to help teens get out-of-state abortions without parental consent. (Tennessee’s law is being challenged in court.) Last month, Texas, the least magical place on earth, introduced SB 2880, which would open providers, funds, and even abortion pill manufacturers up to civil suits. But the ruling in Alabama is a considerable bright spot in the fight for abortion access and could provide a legal boost to the fight against other abortion travel bans. Marty still has concerns—“the state has said that they’re looking at their options”—but, she says, “we are just excited that we are able to provide as much care as we are legally allowed to right now.” AND:

WHEN YOU'RE TIRED BUT YOU PROMISED YOUR CONSTITUENTS YOU WOULD "STAND UP AND SAY SOMETHING" EVEN IF IT MEANT NOT GOING TO THE BATHROOM FOR A FULL DAY. (SCREENSHOT VIA YOUTUBE)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Just Let Everyone Play

Women’s leagues, men’s leagues, and an all-gender league? A new book explores the possibilities.

By Scarlett Harris

In 1902, British figure skater Madge Syers won the silver medal in what was, at the time, an all-men’s World Figure Skating Championships. Until then, women competed only in elite sports perceived as feminine, such as tennis, croquet, and horseback riding, but weren’t explicitly prohibited from competing against men, perhaps because the thought seemed so outlandish. So in 1906, the International Skating Union created the women’s category, which Syers dominated that year and the next, eventually winning gold at the 1908 Olympics.

Syers is widely credited as the reason a “women’s” category in sports competition came to exist—and eventually became the highly lucrative yet highly underestimated women’s leagues of today. Women’s sports are more popular than ever, with viewership rising and even surpassing the men’s league at times, including at last year’s women’s March Madness. Athletes such as Dijonai Carrington, Angel Reese, and Caitlin Clark are now household names. Women’s soccer is the fastest-growing sport in the U.S. and a far more riveting watch than men’s. But—and stay with me here—are sex-segregated leagues the best we can do for gender equality in sports?

In Sheree Bekker and Stephen Mumford’s thought-provoking new book Open Play: The Case for Feminist Sport, the authors argue that women’s sport isn’t necessarily the ultimate feminist goal we’ve been led to believe it is. “It’s rather a form of segregation and control of women to keep them in their own category so that they never beat men or participate on the same footing as them,” charges Bekker, associate professor of health at the University of Bath.

Sex-segregated sports were created so that “women have a chance at winning based on the assumptions that they could never beat men” and to “keep them physically safe in the case of contact sports,” explains Mumford, a philosophy professor at Durham University. “But it’s not really a protected category; it’s a segregated one. Protected categories exist for the protection of those within those categories, whereas segregation exists for the benefit of those outside the segregated group. In other words, the group benefiting is men. “There’s this fear that one day women might actually be able to catch up to and beat men,” Bekker explains. Hence the reason the women’s category was invented in the first place. (Madge Syers, after all, did just that.)

In Open Play, Bekker and Mumford propose the idea of an egalitarian system where competitors are grouped by weight, power, and ability—rather than sex. There are valid concerns that leagues solely based on weight or power may end up suppressing women’s visibility, since, for instance, with basketball, the format would favor men. Still, if Muggsy Bogues was able to keep up with Larry Johnson there’s no reason Sabrina Ionescu couldn’t keep up with Steph Curry. (After all, she already did.)

Succeeding at sport threatens the patriarchy.

Arriving at a time when right-wing lawmakers are using the idea of protecting women athletes for their own political goals, Open Play is much-needed food for thought. President Trump’s two-sex executive order barred the vanishingly small number of trans athletes in this country from participating in women’s sports. “Trans women are not dominating women’s sport at all,” says Mumford. “It’s a manufactured scare. It’s almost at the point where being good at sport is grounds to question someone’s gender because it challenges the perception of how a woman ‘should be.’ Succeeding at [sport] threatens the patriarchy.”

Consider, for instance, the case of Algerian boxer Imane Khelif, a cisgender woman who had her gender called into question during the 2024 Paris Olympics after her opponent forfeited, chargingthat Khelif’s punches were too hard. Or think of South African runner Caster Semenya, who was made to undergo sex verification testing in 2009. Sex testing in sports appears perennially throughout history, from the “nude parades” of the 1950s and ‘60s to chromosomal testing, which World Athletics just announced it would be reintroducing. “We’re starting to see the reemergence of the idea of ‘who is a real woman,’” says Bekker.

But ultimately, gender policing in sport isn’t just about politics—it’s also about money.

Women’s sports get a fraction of the funding, attention, and visibility that men’s sports do. Without sufficient funding, women are working with subpar facilities, which, as the U.S. Women’s National Team argued during their equal pay dispute, can shorten their careers. Under current women’s-league pay conditions, many women athletes also have to work full-time jobs to supplement their paychecks. While elite male athletes are restoring their bodies to squeeze another winning season onto their resume, women like Ilona Maher are running themselves ragged just to keep the lights on. A theory called the 10% gap, which Bekker and Mumford believe to be flawed, posits that men are roughly 10% stronger, faster, and better at sports than women. But “it’s not as if men’s sport is getting 10% more of the funding than women’s sport,” says Mumford. “It’s usually 90% of funding.” Imagine how much better women athletes could perform if they were given access to the degree of training and resources those dollars can buy.

So, would it work for fans? A modern-day Battle of the Sexes might feel like a feminist win, but the rising popularity and viewership of women’s sports could indicate that some people just aren’t interested in watching men compete, regardless of the gender of their opponent. I am a fan of professional wrestling, and while I’m a champion for intergender wrestling and have written about it widely, I still prefer to watch women’s wrestling only. So while a desegregated athletics landscape might be an ultimate goal—at least as an option—for the time being many competitors would likely choose to stay in their current categories.

Non-binary athletes might offer us a glimpse of a more inclusive future, though. USA Gymnastics doesn’t have a specific category for non-binary competitors, and Australian Athletics offers the option to compete in the binary category they feel most comfortable in. And many nonbinary athletes gravitate towards non-traditional sports like roller derby, in which play is often not sex-segregated.

“Non-binary people are showing us the way forward,” Bekker says. “Traditional sports organizations right now are not on top of this and they’re going to lose more people coming into their sport as younger generations, who are more diverse, grow up.”

In the meantime, we’ll have to content ourselves with sportswomen kicking ass in gendered categories—and waiting for the men to be just as interesting to watch.

Scarlett Harris is a culture critic, author of A Diva Was a Female Version of a Wrestler: An Abbreviated Herstory of World Wrestling Entertainment, and editor of The Women Of Jenji Kohan.

What's the Right Way to Miscarry?

March 27, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, You may not have noticed, but today was the worst day of the year: Opening Day. If those words mean nothing to you, then congratulations on having peace in your life. But if, like me, you happen to live with or tolerate an unbearable Yankees fan, then my heart goes out to you. Be strong. In today’s newsletter, another woman’s pregnancy is being criminalized in the state of Georgia. Plus, Rebecca Carroll writes about the unspoken lessons of the new Netflix hit Adolescence, and your weekend reading list. Do NOT take me out to the ball game, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONThe “right” way to miscarry: Last week, a young woman in Georgia named Selena Chandler-Scott was arrested and charged with “concealing the death of another person” and “abandonment of a dead body.” A cold-blooded murderer? No—a woman who had suffered a miscarriage and disposed of the remains in the dumpster outside her apartment complex. Journalist Jessica Valenti, who has been tracking this story, asks the right question here “Was she supposed to call the police after her miscarriage? A funeral home? At what point in pregnancy are women supposed to start reporting their pregnancy losses to law enforcement?” Chandler-Scott is not the first woman to be punished for miscarrying outside of a hospital where fetal remains can be “properly” disposed of. Last summer, also in Georgia, a young woman was placed under investigation after miscarrying in a public bathroom and placing her fetal remains in a trash can (no formal charges were filed; however, the fetus was sent for an autopsy, which is also what’s happening in the Chandler-Scott case). Just a few months later, Brittany Watts of Ohio was charged with felony abuse of a corpse after she miscarried at home and flushed the remains. A court declined to indict her, but Watts should never have been arrested in the first place. Prosecutors in these cases are banking on the fact that when people hear “fetal remains in a trash can,” they’ll react with disgust or disdain. But let’s back up: What should you do if you miscarry? The general advice is to seek medical care. But that’s exactly what Brittany Watts did, and the hospital declined to treat her because of Ohio’s abortion laws. She was sent back home where she miscarried, and later returned to that hospital for help with persistent bleeding. A nurse called the police, who went to Watts’ house and destroyed her bathroom searching for remains. It’s not hard to imagine Chandler-Scott’s case following the same trajectory had she gone to a hospital—and it’s easy to imagine why she, or any other woman, might currently decide not to do so. So if in a post-Dobbs America, home is not safe and hospitals are not safe, what is the “right” way to miscarry? Unfortunately, women like Selena Chandler-Scott will have to learn the answer to that from a jail cell. If you need help navigating a miscarriage or abortion, you can call or text the M+A Hotline for more information. AND:

Netflix’s Adolescence Isn’t About Race, Except Maybe it IsThe hit show provokes an empathy that Black boys seldom getBY REBECCA CARROLL  (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Everyone is talking about Adolescence, the new Netflix drama that tells the harrowing story of a 13-year-old boy who is accused of killing his classmate, a girl named Katie. As a mother, I watched it as a cautionary tale about the perils of violent incel culture on the still-developing brains of young boys. But as a Black cultural critic who is also the mother of a Black boy, it also made me think about who we feel empathy for, and who we do not. To be clear, I loved Adolescence. Each episode is shot in one remarkable take, every scene strung together like a grievous aria. The effect is gutting. At the center of the show is 13-year-old Jamie Miller (Owen Cooper), a baby-faced schoolboy with alabaster skin, brooding eyes, and a sullen British lilt. Jamie lives with his working-class family in the small town of West Yorkshire, England, and has been accused of the stabbing murder of his classmate. There are no spoilers to be had—damning video evidence is revealed in the first episode. The rest of the series unfolds the devastating aftermath of Jamie’s crime; the unraveling of his family following his arrest and incarceration; and the painstaking path to understanding his motivations. It is a path paved with compassion. Jamie is presented as a victim of the manosphere, spending all those unsupervised hours holed up in his room, delving deep into a misogynist world online and on social media. By the end of the series, I was still somewhat rooting for this white boy who, yes, was a target of cyberbullying and the coded emoji world of Instagram, but who also committed a violent murder. This show made me worry about men, and I never worry about men. But my empathy speaks volumes about how we are all conditioned to receive and accept the way this boy is presented—and the fact that he is not demonized, a grace seldom offered to young Black boys.  WEEKEND READING 📚On being an “old soul”: Please enjoy this delightful profile of The Last of Us star (and Pedro Pascal bestie) Bella Ramsey, whose recent diagnosis of autism enables them “to walk through the world with more grace towards [themselves].” (British Vogue) On the new lavender scare: McCarthy-era purges of gay and lesbian people offer an unsettling parallel to what’s happening today in the federal government. Trans workers explain what the last couple of months have been like at work. (Slate) On health: What do we lose when the word “women” is banned from medical research? (The 19th)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Everything's Bigger in Texas...Including Abortion Bans

March 20, 2025 Greetings and glad tidings, Meteor readers, ‘Tis the spring equinox! Time to go outside and frolic in the forests. Good luck finding an egg-laying rabbit.  In today’s newsletter, we are, for the umpteenth time, talking about Texas. Plus, the long-awaited executive order attempting to get rid of the Department of Education, and your weekend reading list. Tree huggin, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONTen-gallon nightmare: Last Friday, Texas state senator Bryan Hughes introduced the most expansive anti-abortion bill the state has seen since the overturn of Roe v. Wade. Get comfortable, because we’re going to be here a while. What’s in SB 2880? Well…everything, basically. The bill allows for anyone to file a civil lawsuit against a company or individual for playing any part in facilitating an abortion in Texas or for a Texas resident. Individuals and groups can also be sued for being an “information content provider.” As journalist Jessica Valenti points out in her coverage of the bill, even apps like Venmo and Signal could get sued for their part in an abortion. “If the bill worked, it would be a lot harder to find information about abortion online in Texas and potentially everywhere else,” another abortion expert told The 19th. Since “the internet is the same everywhere,” this law could potentially be used to attack companies throughout the United States that host abortion information. The bill also allows for the “biological father” of an “unborn child” to bring a wrongful death suit against abortion providers in any state, regardless of his relationship to the mother. (Yes, even one-night stands.) There is a carve-out in the law that stipulates a man cannot bring a suit if the child was conceived from an act of sexual assault, but we’re betting it’ll be about as effective as other rape-and-incest exceptions in abortion bans. (That is to say, not very.) But wait! There’s more. This bill gets extremely particular about medication abortion, allowing civil actions against people who “manufacture, possess, distribute, mail, transport, deliver, prescribe, or provide an abortion-inducing drug in any manner to or from any person or location” in Texas. Bought some pills from heyjane.com to stockpile in case of emergency? Lawsuit! Live in a blue state and mailed pills to your friend in need who happens to live in Texas? Lawsuit! Once again, there is a carve-out for any emergencies related to preserving the life of the mother, but as we’ve seen in a number of cases out of Texas, that doesn’t always work in real life. I hope you don’t think we’re done yet. SB 2880 is so nefariously thorough that abortion funds are also caught in the crosshairs. The bill would make it a felony for an individual or group to pay for or reimburse any costs incurred by obtaining an abortion, including the costs of traveling out of state for care. That $20 you gave someone for gas to get to a clinic across state lines? A second-degree felony if this bill becomes law. In fact, if I tell you right now to go support Fund Texas Choice, I could potentially be sued when this bill passes, as could my boss for owning a website supplying this information, as could my editor, Nona, who has to edit these long, rambling sentences. You, on the other hand, could be subject to a criminal suit because you actually sent the money. That is how thorough it is. In the words of a famous Texan, ring the alarm. The bill was read for the first time in the state senate yesterday and has already been referred to the committee for State Affairs. Should it pass and be signed, the law would go into effect in September—but will probably face a number of challenges in court from abortion rights and First Amendment groups. If you live in Texas, call your state senator. If you don’t, continue supporting abortion funds until you can’t anymore. AND:

RUINING KIDS' FUTURES RIGHT IN FRONT OF THEM. BOLD. (VIA GETTY)

MY HEART WILL GO ON. (VIA INSTAGRAM)

WEEKEND READING 📚On denial: Earlier this month the Trump administration received a petition to grant Puerto Rico’s independence via executive order. The move has had a chilling and divisive effect on the island. (The Latino Newsletter) On the end of an era: An inside look at the final days of Voice of America. (Columbia Journalism Review) On the record: Elon Musk’s fearless estranged daughter calls him a “pathetic man-child.” (Teen Vogue)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Why Did Texas Target This Midwife?

March 18, 2025 Hey there, Meteor readers, Bad Bunny and Calvin Klein. I will not be elaborating any further. In today’s newsletter, we grapple with the broader implications of a midwife’s arrest in Texas. Plus, the Trump administration faces off with the judicial branch. Orgullosa, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONEasy targets: Yesterday, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton’s office announced the arrest of a Texas-based midwife, Maria Margarita Rojas; two of her employees were arrested later. Rojas, who was reportedly arrested at gunpoint, and Jose Cendan Ley have been charged with “illegal performance of an abortion” and allegedly practicing medicine without a license, while Rubildo Labanino Matos was charged with conspiracy to practice medicine without a license. This appears to be the first arrest of a provider since the overturn of Roe v. Wade. We don’t yet have too many details on this case, other than statements from Paxton’s office which, as writer Jessica Valenti points out, will only reflect the state’s official framing. Valenti also suggests that the targets themselves are handpicked. “Republicans are strategically targeting people they think the public won’t rally behind,” she writes. And they’re also targeting the people who are serving the most vulnerable: Just the day before Rojas’s arrest was announced, a study of 2023 birth data from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that the fall of Roe v. Wade had disproportionately denied abortions to Hispanic women, poor women, women without a college degree, and women living furthest from abortion providers. These are some of the women Rojas served: Waller County, Texas—where one of her Houston-area health clinics is located—has a more than 30% Hispanic population and a 14% poverty rate. The Houston area is also more than 500 miles away from the nearest abortion clinic. But what makes Paxton so sure the public won't rally behind Rojas and her employees? The answer can be found in his two statements announcing the arrests, where Paxton makes sure to note that Matos and Ley are not U.S.-born—a fact that has no bearing on their charges. It does, however, have a lot to do with Paxton’s anti-immigrant track record. This is the same man who put floating “death traps” in the Rio Grande to prevent immigrants from crossing into Texas. The fact that Ley and Matos are both Cuban nationals and that Rojas was born in Peru is catnip to a man who seeks to eliminate from his state both abortion and immigrants. Paxton and those who support him are relying on the fact that the community Rojas and her clinics served won’t speak up for her because she worked with Spanish-speaking, low-income clients who already contend with a litany of safety concerns. Immigrant communities are already under immense strain with ICE now targeting and detaining people regardless of their legal status. As Farah Diaz-Tello of If/When/How noted to The Cut, former patients “might be worried whether they can be criminally prosecuted, whether their private health information is now gonna be used as part of the criminal prosecution against the provider.” The state still has to prove its cases against Rojas, Matos, and Ley, and we will keep you updated as this story unfolds. But what these initial facts have made clear is that the war on abortion is most focused on the people with the least power in America: anyone who can get pregnant, poor people, people of color, and immigrants. You can help those being prosecuted for abortion-related activities by supporting the Abortion Defense Network or the Repro Legal Defense Fund. AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Pissed Off About Insurance? So Are These Doctors

Physicians are publicly calling out red tape and immoral practices. Vivian Manning-Schaffel gets the story.

Dr. Elisabeth Potter was still wearing a scrub cap when she fired off a now-viral Instagram post that took direct aim at the biggest health insurance company in the country. In her post, she talked about having to scrub out of surgery to hop on an urgent authorization call with United Healthcare, which was asking for details about her patient’s diagnosis and whether her overnight hospital stay was justified.

“Do you understand that she's asleep right now? And that she has breast cancer?” Potter, a Texas-based board-certified plastic surgeon and breast cancer reconstruction specialist, says she told the rep on the phone. “Actually, I don’t. That’s a different department,” she says the rep replied. “When I get a call from an insurance company for a woman with breast cancer, I always think they're going to try to deny her surgery,” she told The Meteor. After her post went viral, she shared another post on Instagram, a strongly worded letter from the attorneys of United Healthcare demanding that she take her post down, issue a public apology, and inform Newsweek that her “claims were false."

Then, she went on CNN.

It’s rare to see a doctor putting an insurance company on blast—partly because threats of legal action can be daunting for already overworked providers. Potter has long been the exception, taking to the morning-show circuit five years ago to advocate for safer breast implants despite what she called “bullying and pressure” from insurance companies. But since Potter’s post went viral, the floodgates have opened. Doctors like Washington, D.C. critical care physician Dr. Anita Patel, who recently took on Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield for attempting to impose time limits on anesthesia, and Florida breast cancer surgeon Dr. Alicia Billington, who took Cigna to task for what she saw as failing to adequately cover reconstructive surgeries, have gotten more vocal about healthcare industry practices that they say sacrifice the well-being of their patients.

THE NIGHTMARE OF “PEER-TO-PEER” CALLS

Dr. Shikha Jain, a hematologist and oncologist at the University of Illinois Cancer Center, has often used social media to amplify unjust insurance practices, tweeting about how insurance companies have delayed her patients’ urgent scans, denied coverage of a cancer combo therapy, and kept her on hour-long peer-to-peer calls. These delays and denials—which Dr. Jain calls “insurance scams”—are “all because insurance companies are just trying to save a buck and don't care about the patients’ lives,” she said. Her online advocacy has led to op-eds, TV interviews, and an appearance in a New York Times Opinion video piece.

“When I get a call from an insurance company for a woman with breast cancer, I always think they're going to try to deny her surgery”—Dr. Elisabeth Potter

One of Dr. Jain’s pet peeves? Those so-called “peer-to-peer” calls, like the one Dr. Potter had to make during surgery, when an insurance company doctor will speak with a patient’s doctor to verify the need for coverage. She’s missed peer-to-peer calls during busy clinic hours, when she sees patients back-to-back, and because she’s missed them, the insurance company denied the claim, she says. This requires the patient to appeal the decision, which can take several months.

What’s worse, the doctors interviewed say, the calls that can make or break a patient’s coverage aren’t always with doctors who share their specialty or expertise, sometimes resulting in significant care delays and perilous health risks for their patients. “You are the person, sitting in the room with the patient...crying with them because their chemotherapy has been denied,” Dr. Jain says, while “somebody who has never seen a patient with this disease is sitting at a computer a thousand miles away, making decisions based on an algorithm that is set up to deny care.”

Dr. Anita K. Patel, a pediatric critical care physician at a large children’s hospital in Washington, D.C. says she recently called out Anthem BCBS “100% in response” to Dr. Potter’s own post about the company’s announcement that it would put time limits on anesthesia (a decision it has since reversed due to widespread backlash). “I work in an ICU for kids,” says Patel. “We would get notifications they were denying coverage.” She often finds herself on peer-to-peer calls fighting for life-or-death necessities like ventilators and wheelchairs. She once spent what she describes as a “demoralizing” hour in circles with an attending physician on the insurance side who was intent on denying an ICU stay to a vulnerable child with a life-threatening neurologic injury. “Any delay of care could cost the kid their life, and there was no way the parents could afford the bill,” she said.

“NOBODY WANTS TO BE IN THE HOT SEAT”

So what can patients do when they’re at wits’ and wallets’ end with the insurance system? Besides keeping meticulous records of each contact with an insurance company and urging one’s workplace to pick plans that prioritize women’s health, Dr. Potter hopes patients will use social media for accountability, too. “I want to see open conversations about the nitty-gritty details of healthcare and the dark stories in courtrooms being had by providers and patients,” she says. But Dr. Jain says that while patients calling out insurance companies on social media can be effective, she understands why it could be the last thing they want to do. “How horrible is it if you're being treated for cancer,” she says, “then on top of that having to go to social media and fight for your ability just to get treated? That's not right.”

It may not be right, but the discomfort of publicly pressuring insurance companies could lead to more meaningful reform. Though, it may be a long road. While editing this piece, Dr. Potter fired off another IG post saying another patient came to her with a denial from United. “Nobody wants to be in the hot seat,” Dr. Potter says, “but I want to make it more comfortable for doctors and patients to say insurance and hospitals are doing things that are not good for patients, and not good for providers.”

Vivian Manning-Schaffel is a journalist and essayist who covers entertainment, culture, psychology, and women’s health. Her Substack, MUTHR, FCKD, covers pop culture through a feminist Gen X lens.

Are Protests Now "Terrorism?"

March 11, 2025 The weather is absolutely gorgeous in New Jersey, which means it is officially hiking season for me and my mini. We’re packin’ snacks, makin’ tracks, and yelling “dog” every time we see one. And speaking of sunny optimism, thanks to all of you who turned out for our International Women’s Day event at the Brooklyn Museum last Saturday! We loved seeing every one of you almost as much as Aurora James loved seeing Diane von Furstenberg.  ALL LOVE! (PHOTO BY REDENS DESROSIERS) In today’s newsletter, we look at the larger impact of a student arrest, plus a frightening report on who exactly is in our state legislatures. Plus, the second annual Meteor Madness bracket group is now open. From the trail, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONA green card didn’t save him: On Saturday, Mahmoud Khalil, a former graduate student at Columbia University in New York and a vocal member of the pro-Palestinian movement on campus, was arrested by Department of Homeland Security officers in the lobby of his university-owned apartment building. According to Khalil’s attorney, who spoke to NPR, he was told by the arresting officers that he was being apprehended because his student visa had been canceled. When Khalil, who is Palestinian, told officers that he was a legal permanent resident with a green card, they said that his green card had been revoked, too. He was arrested without a warrant, and for several hours, his lawyers and his wife could not find him. He is now in a detention center in Louisiana—although attempts to deport him were temporarily blocked by a federal judge on Monday morning. A little context: Khalil’s arrest comes on the heels of an executive order issued by Donald Trump which promised to detain and deport “Hamas sympathizers on college campuses” and any non-citizen who “endorses or espouses terrorist activity.” (There is no evidence he has committed a “criminal offense,” The Atlantic reported. ) But Trump is still taking a twisted victory lap, posting on Truth Social: “This is the first arrest of many to come,” he wrote, calling protesters “paid agitators” and “terrorist sympathizers.” Khalil has not been charged with a crime, nor is there proof that he’s a “paid agitator.” There’s no evidence that he’s said anything threatening or violent. He was, however, a very visible protester of the genocide in Gaza. He’s a leader of Columbia University Apartheid Divest (CUAD), a coalition demanding the school’s divestment from Israel. A quick search of Khalil will turn up photos of him at protests, sit-ins, rallies, and encampments. But those activities—per the Constitution!—are not crimes. So let’s be clear: Mahmoud Khalil is a political prisoner, punished for exercising his First Amendment rights. A lot of us are rightly up in arms about Khalil’s arrest—an arrest that feels ironic because Mahmoud Khalil is what the state would normally consider a “model minority.” He has a master’s degree from a prestigious institution, he’s a husband and soon-to-be father, and he presented a green card at the time of his arrest. But none of that saved him—all because he expressed views the government disagreed with.  PROTESTORS GATHERING ON KHALIL'S BEHALF IN NEW YORK CITY. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) So as social-media users have been asking: If basic human rights are not extended to people like Khalil, who is protected? If you can disappear someone with a green card, who can’t you disappear? These are fair questions. It’s also worth a reminder that other vulnerable people’s rights were taken away recently with far less outcry. In January, the bipartisan Laken Riley Act rendered due process a thing of the past for undocumented immigrants; the bill is apparently a driving force in the increase in targeted ICE raids. Just last month, more than 100 Venezuelans —some of whom had no criminal charges against them—were also “disappeared” after being detained in Guantanamo Bay. What’s being done to Khalil is egregious, but it’s not isolated. Like many immigrants, Khalil sensed he could become a target and reached out for help, only for it to fall on deaf ears. When the president of the United States promised months ago that he was coming for everyone who was against him, we should have believed him—and not waited until he came for someone with a green card. AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()