The Pope's Declaration May Feel Late...But It's Still Important

December 19, 2023 Ho, ho, ho, Meteor readers, Only a few more days ‘til Christmas, and I, for one, am very much looking forward to cooking my family’s ancestral holiday dinner, passed down to me by generations of Puerto Rican women: lasagna. In today’s newsletter, Phill Picardi helps us make sense of Pope Francis’s latest announcement—plus, a new bill to save books and a touch of, yes, good news. No-boil noodles for the win, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S IT REALLY MEAN?Yesterday, Pope Francis issued a declaration stating that priests are now allowed to bless same-sex couples. There is, of course, a caveat: The blessings must be in line with the teachings of the Catholic Church. This means that while those couples can be blessed, they still cannot receive the sacrament of holy matrimony, and their marriages cannot be formally recognized by the Church. Still, this is a bold step forward for Francis, who has been fending off conservative attacks from within the Vatican walls and, in the U.S., the overall influence of the political right. How happy should or shouldn’t we be about this? We knew exactly who to ask: Meteor collective member Phillip Picardi, who is both the CMO of the LA LGBT Center and a graduate of Harvard Divinity School. What does this new document from the Vatican mean for the LGBTQ+ Catholic community? Phillip Picardi: This is the rare headline about Christianity and LGBTQ+ people that doesn’t involve violent protests, book bans, or the rollback of basic civil rights. Instead, this is the Pope—who’s believed by Catholics to be the divinely ordained Head of the Church—telling his global clergy that they can bless LGBTQ+ couples. This is a massive turnaround, considering the Church’s hard-nosed stances on gay adoption, same-sex marriage, trans rights, and even safe sex practices around HIV/AIDS. Now, while a blessing isn’t going to solve the issues facing our community, it can’t hurt. Religious-based discrimination is a huge issue for the LGBTQ+ community—in fact, many of the youth who end up seeking housing with the LGBT Center [have been] kicked out of their homes for reasons related to religion. If this starts to change some of that harmful rhetoric, it can be significant. The declaration makes a point to distinguish between allowing same-sex couples a blessing rather than allowing them to receive the sacrament of matrimony. What’s the difference between these two things? Sacraments are the ways a Catholic moves through their journey within the church throughout their life. They’re liturgical sacraments, which means that they hold a certain rigor within the structure of the Church. Catholicism is very big on making sure Catholics have been educated and prepared before receiving these sacraments because, in a sense, they’re also a reception of God. A blessing is a much more casual acknowledgment by a clergy member; it doesn't hold the same liturgical rigor. Pope Francis, with this order, is trying to make it so that Catholic priests feel comfortable giving blessings to folks, even though they may not know about their moral litmus test. Before, getting a blessing from the Church was something that the Vatican said you needed to be somewhat morally pure or prepared for. So, he's removing this idea that there needs to be a moral exam for someone to receive a blessing or acknowledgment from the church. Is this a big step forward? Or not big enough? I think that depends on your own relationship to faith. If you are not Catholic, a move like this from the Pope can seem inconsequential or rudimentary—a small spiritual concession to make. And I think that can be a fair assessment considering how far other faith traditions have come on LGBTQ+ issues. On the other hand, if you are Catholic and know about the history of the Church, this can feel massive. Pope Francis is breaking with centuries of tradition that have seen the Church further marginalize and harm LGBTQ+ people. He’s also issuing this sort of “spiritual executive order” at a time when the Catholic church is, unfortunately, tilting even farther towards the right. The Pope has the power to change how Catholics look at their neighbors or how a parent looks at their child. Even for LGBTQ+ Catholics—because it’s estimated that at least half of our community is religious!—this is significant. It can feel like an opportunity for healing or reconciliation after a lifetime of religious-based trauma, after feeling abandoned by a church community or even by God. And if this is the beginning of that change—then this is a positive step in the right direction. ALSO IN THE NEWS

TELL ME SOMETHIN' GOOD 🎶

CLICK THE LINK ABOVE TO GET YOUR UNIQUE SHARE CODE TO SEND TO A FEW FRIENDS. IF FIVE OF THEM SIGN UP FOR THIS NEWSLETTER, YOU GET A METEOR TOTE! ALREADY HAVE A CODE BUT CAN'T FIND IT? NO WORRIES, IT'S WAITING FOR YOU DOWN BELOW ⬇️

1 Any promises of children being exchanged for goods and services are not legally binding. FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

A Crucial Year Ahead for Abortion Access

NEWS

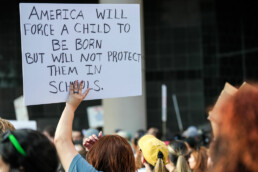

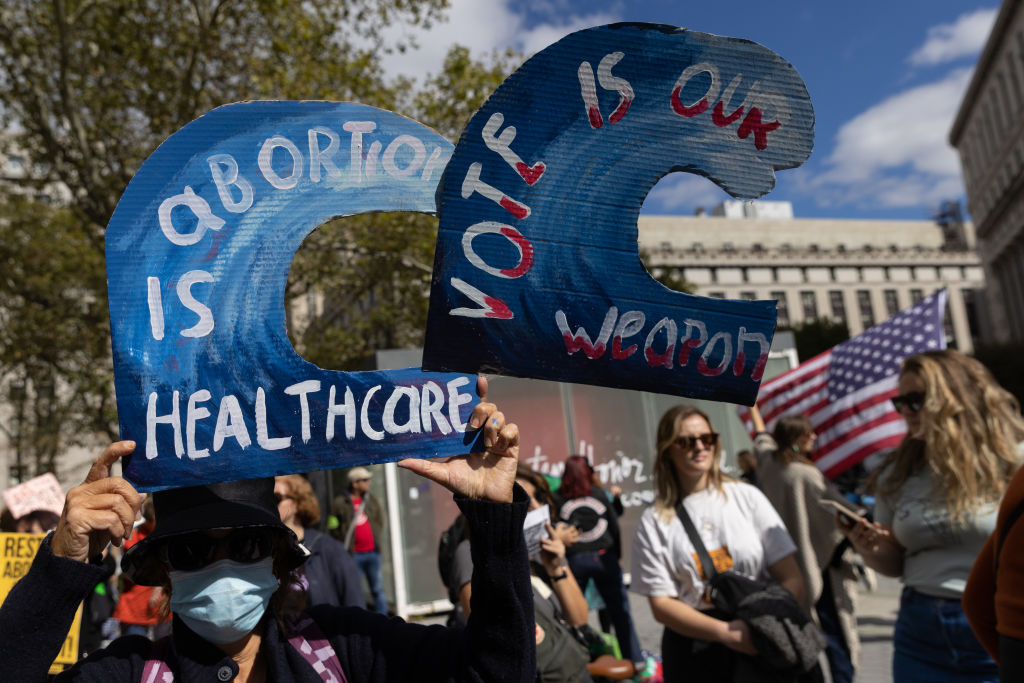

Why legislative decisions will matter more than ever in the second year since Roe was overturned

BY SUSAN RINKUNAS

It has been nearly 18 months since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, and the impact of the laws that have come to life since have had devastating consequences for pregnant people. One after another, we’ve read awful stories of patients being rushed to the ICU with sepsis, nearly bleeding out in bathrooms, or having to go out of state for abortions when their fetuses don’t have skulls.

Amid all this news, it can be hard to pinpoint a bright spot, but there is one: Support for abortion has repeatedly won elections. In what would have otherwise been a sleepy off-year of races, voters were so furious about their rights being taken away that they re-elected a Democrat as Governor in Kentucky, codified abortion in Ohio, and flipped a chamber in Virginia, blocking a ban there.

Republicans know their plan to ban abortion in every state is toxic with voters, so they’re trying to deceive people from their end goal. It’s why we’ve seen conservative hand-wringing over the label “pro-life,” attempts to deflect with transphobia, and, yes, even backing away from the word “ban” in favor of “limit” or “minimum standard.”

But, according to Ryan Stitzlein, vice president of political and government relations at Reproductive Freedom for All, voters have shown a sustained fury over the abortion access crisis, and it stands to reason that they’ll keep it up. A major problem, however, is that our democracy isn’t the most democratic, and the majority doesn’t always prevail. (See: 2016.) Amid all the righteous anger, there’s a lurking threat that a Republican president could ban abortion nationwide.

“This is not us being ‘hysterical.’ This is real,” Stitzlein says. “They’re not going to stop until they’ve completely banned abortion.”

As we close out another year of egregious cutbacks to abortion access, here’s what we can expect in 2024.

Abortion policy duked out at the state level

As advocates long warned, the fight for abortion is playing out at the state level and in the courts. There are now 16 states with near-total bans on abortion after laws took effect in Indiana and North Dakota this year, and another four states ban the procedure at 15 weeks of pregnancy or earlier. State lawmakers have the opportunity to block restrictions, pass protections for patients and providers, or even introduce messaging bills on abortion that inform people about threats they face, says Jennifer Driver, senior director of reproductive rights at the State Innovation Exchange (SiX) Action.

Criminalization of providers and patients

In response to threats against telemedicine providers, legislatures in states where abortion is protected are passing “shield laws” to legally protect providers who treat patients across state lines. Still, Driver says those laws are untested as of yet. As for the criminalization of patients, the Nevada legislature could repeal its ban on self-managed abortion, she says—it’s the only state with such a ban left on the books. However, prosecutors can and do weaponize other statutes to criminalize people for behavior during their pregnancy or for pregnancy loss.

Insurance fights

Lawmakers in states like Colorado, New Jersey, and Rhode Island are also doing what they can to expand insurance coverage of abortion, whether through Medicaid or by requiring private insurance plans to cover the procedure without cost-sharing, says Kimya Forouzan, principal policy associate for state issues at the Guttmacher Institute. But it’s not all smooth sailing. In Michigan, one Democrat’s objection to Medicaid coverage effectively ended that effort. Still, the state was able to end the requirement that people with private insurance purchase a separate coverage rider for abortion.

Crisis pregnancy centers

Forouzan says protective states are also moving to regulate anti-abortion crisis pregnancy centers under deceptive advertising statutes, but anti-abortion advocates have sued on First Amendment grounds. Those lawsuits could move their way through the court system in 2024. Conservative states will continue to funnel money and tax credits to CPCs, the vast majority of which offer no legitimate medical care.

Travel bans

In conservative states, the next frontier in the fight against access is restricting travel, Driver says. Idaho passed a law banning people from taking minors out of state for abortions without parental consent, and conservative activists like Jonathan Mitchell and Mark Lee Dickson have been working at the city and county level to try to ban people from driving abortion-seekers on Texas highways to appointments out of state. These attacks seem blatantly unconstitutional, but Forouzan notes that judges don’t need to uphold the ordinances for them to cause harm. “For many people who are trying to access abortion care, hearing that travel is banned or even just vaguely hearing that they could get in trouble or become criminalized for it is enough to dissuade people to not seek care,” she says.

Overlap with anti-trans rhetoric

Forouzan says we can expect to see more politicians connect attacks on abortion access to attacks on gender-affirming care. She cites as examples how Nebraska lawmakers first failed to pass a six-week ban but then later attached a 12-week ban to a bill banning affirming care for transgender youth. And in Ohio, opponents of the ballot measure tried to claim it would protect gender-affirming care.

Local elections and ballot measures

State legislators—who determine the fate of many of these laws—will be up for re-election next fall. Arizona will be a big state to watch that could flip to Democratic control. (The state has a 15-week ban in place, but a Democratic governor.) Driver predicts more candidates for state houses will lean into abortion in their campaigns like they did in Virginia this year. “This was the first time that I had seen candidates actually position themselves against their opponents by saying ‘I am the person that is going to protect access,’” she says. She’ll also be watching to see if conservatives in tough races double down on abortion or backtrack from the issue to try to keep their jobs.

Court appointments will also be crucial: It’s possible access could be fully restored in Wisconsin in 2024, thanks to a Democrat flipping control of the state Supreme Court earlier this year. In Florida, where the Governor appoints state Supreme Court justices, an impending ruling could slash the window of access down from 15 weeks to six—it would be a gigantic blow to the Southeast. There will be many other crucial state races for Governor and Attorney General—electeds who choose whether to sign or veto bills into law and how to enforce them.

And, yes, there are pro-choice ballot measures in the works in about 12 more states for 2024—including in states with active bans—where voters could make a difference. Surely, the victory in Ohio rattled the anti-abortion side: It was the seventh pro-choice victory since the Dobbs decision, and the first affirmative vote in a red state. Already, Ohio lawmakers started scheming ways to weaken it.

Continual erosion of democracy

We could see states use the coming legislative session to try to restrict the citizen-led referendum process by ending it altogether, raising the threshold for passage, or exempting abortion from statewide votes, Driver says. There’s a connection between the erosion of both democracy and abortion rights—bans pass in gerrymandered legislatures. These most recent efforts are “a sign that anti-abortion leaders are really ready to reject the will of the people,” she says.

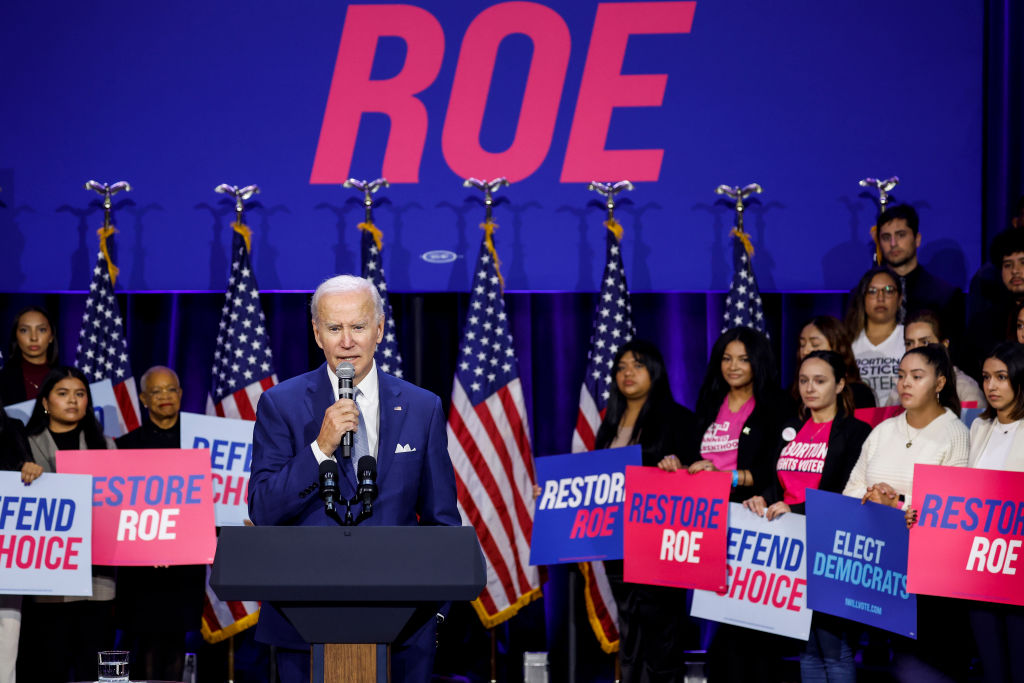

The national fight to protect access

Stitzlein says ballot measures can be “hugely impactful,” but the threat of a nationwide ban still exists. To fix the abortion crisis in the U.S., there needs to be a federal law protecting access to the procedure. The way to do that, he says, is to re-elect Joe Biden and send him Democratic majorities in the House and Senate. Candidates need to run pro-actively on the message of codifying abortion rights and remind voters in states like Ohio that the work isn’t over.

“Reasonable” Republicans

We’re already seeing GOP presidential candidates shift to a faux-moderate position, and Stitzlein expects it to continue as candidates up and down the ballot try to hide their ultimate goal: banning abortion everywhere. Voters will be hit with a barrage of messaging from Republicans who swear that there won’t be a nationwide ban—either because a ban won’t pass Congress, like Nikki Haley and Ron DeSantis have claimed, or because abortion should be a state issue, as Kari Lake said in a recent reversal of her position. These are, of course, gigantic lies spun out of political desperation. “The fact that you have people like Donald Trump and Kari Lake—of all people—trying to present themselves as moderates on abortion is demonstrative in and of itself of just how toxic this issue is,” Stitzlein says.

Banning abortion without Congress

Contrary to what multiple Republican candidates have said, legislation isn’t the only way a GOP President could ban abortion in 2025. They could simply direct the Department of Justice to enforce the Comstock Act of 1873, a zombie anti-vice law that prohibits mailing items used for abortion. The law is still on the books but wasn’t enforced while Roe stood. Now, conservative groups, including the Heritage Foundation, are urging a potential GOP administration to invoke the law to ban the mailing of abortion pills, though Comstock could be used to end all abortions. So, yes, there’s a world in which Trump wins in 2024, doesn’t have enough Senate votes to pass a law, but can ban abortion regardless.

The impact of Trump judges

If Biden wins but Democrats lose the Senate, it’s unlikely he’d be able to nominate federal judges or fill any potential Supreme Court vacancies. It’s worth repeating that the reason Roe was overturned and we’re facing the threat of a nationwide abortion ban is because Trump appointed three justices in a single term.

A legacy of the Trump administration is packing the court system with far-right activist judges, Stitzlein says, and there’s no more significant example than Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk in Texas. Kacsmaryk ruled in April to revoke FDA approval of the abortion pill mifepristone, and the Supreme Court just decided to hear the case. That lawsuit is another threat flying under the radar, Driver says. “I’m having to remind [state] legislators this case is still happening,” she says. “The everyday person is not following along.” Kacsmaryk is the judge in two other cases, one that could bankrupt a Planned Parenthood affiliate in Texas (and possibly the entire organization), and another that could imperil birth control access for minors at federally-funded clinics. Even if Biden wins, these lawsuits—and all those Trump judges—aren’t going anywhere.

Be mad, stay mad

“We’ve seen this huge surge in turnout every time abortion has been on the ballot, and we expect that to continue to grow in intensity the longer we’re in this crisis,” Stitzlein says. But U.S. voters have a lot of reasons to be mad, including the high cost of living, ongoing wars, and lack of progress on climate action and student loans. There’s still a chance that abortion rage might not be enough to keep authoritarians out of office. After all, Biden only beat Trump in the Electoral College by 44,000 votes in three states. About a year out, it’s not impossible to imagine that vote margin evaporating and the rights of millions of people along with it.

Susan Rinkunas is a reporter covering abortion, reproductive health, and politics. Her work has appeared in Jezebel, The Guardian, Slate, NBC News, Elle, and more.

Kate Cox Should've Had a Choice

December 12, 2023 Greetings, Meteor readers, I know that it’s not cool to scold people, but some of y’all deserve it. Stop sending money to George Santos on Cameo! It was funny when he was lying and scamming his way around Congress, but this man should not be profiting off his nonsense to the tune of $174,000. Honestly, if you want to pay that much to have someone sassy insult your friends, I’ve got a Venmo account, way better lighting, and have never been expelled from Congress. In today’s newsletter, we read between the lines of Texas’s Supreme Court ruling against Kate Cox. Plus, a ceasefire in the Congo and a reprieve for children apprehended at the U.S. southern border. Reminding you Santos Cameos are not in your budget, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONAn inhumane ruling: The story of Kate Cox, a Texas woman who sued, won, and then eventually lost her fight to obtain an abortion in her state has dominated the headlines over the last few days. So what makes this case such a huge story? Let’s start from the top. Kate Cox found out in November that her pregnancy was doomed. During an NIPT screening (between 10-13 weeks) meant to determine the sex of the fetus, Cox’s doctor found markers that the fetus was at high risk for Trisomy 18, “a condition with a very high likelihood of miscarriage or stillbirth and low survival rates.” Despite these initial results, Cox remained hopeful and underwent further testing, which only revealed worsening conditions for her fetus, including irregular skull and heart development, a twisted spine, and a neural tube defect. A specialist told Cox that in the best-case scenario—if the fetus managed to survive labor—it would only live for a week. Cox was devastated. Not only was her pregnancy not viable, there was a chance carrying it to term would impact her ability to conceive in the future. And yet, she was told by her medical professionals that she didn’t meet the legal threshold to obtain an abortion because of the extreme ban in Texas—a story shared by many other women in the state (and across the country) since the Dobbs decision. With the support of a doctor who was willing to perform the abortion, Cox quickly sued the state to request an exemption, given the dangerous medical circumstances surrounding her pregnancy. Last Friday, a lower court ruled in her favor—but shortly after Attorney General Ken Paxton appealed the decision, and the case was sent to Texas’s Supreme Court. On Monday, the highest court in Texas, much to the shock of medical professionals and advocates, overturned the lower court's decision. They ruled that Cox was not eligible for an abortion under the state’s guidelines. (Instead of waiting for her condition to worsen, Cox sought an abortion out of state just before the ruling was issued.) What is truly baffling about the ruling issued by the court are the linguistic gymnastics used by the justices to explain the decision. They place most of the blame on her doctor, writing that the physician had failed to meet a standard from the Texas ban that allows an abortion “if the pregnant female…has a life-threatening physical condition aggravated by, caused by, or arising from a pregnancy that places the female at risk of death or poses a serious risk of substantial impairment of a major bodily function.” Let’s pause here. At the point in which the suit was filed, Kate Cox’s life was not in immediate danger, and (ostensibly) potentially not being able to conceive again falls under “impairment to a major bodily function.” The fact that these laws are written in such a way that doctors have to hesitate in making the decisions that are best for their patients for fear they might have their licenses revoked or prosecuted is anything but “pro-life.” It’s a double-edged sword that even the Court was forced to acknowledge in its ruling: “Under the law,” the justices wrote, “it is a doctor who must decide that a woman is suffering from a life-threatening condition during a pregnancy, raising the necessity for an abortion…A pregnant woman does not need a court order to have a lifesaving abortion in Texas.” Unfortunately, Justices Devine and Blacklock, under your state’s law, she does. But she absolutely should not have to. AND:

MORE FROM THE METEORIf you’re in New York this weekend: In Love and Struggle, Vol. 3 is happening at the Minetta Lane Theatre! Come hang out with us on December 14, 15, or 16 and see performances from voice actor Cree Summer, comedian Zainab Johnson, poet Mahogany L. Browne, musician Nona Hendryx (she was one of the singers on the original Lady Marmalade!!!), and many more. You can get your tickets (and a sweet discount) here. If you’re looking for a podcast: Last week, In Retrospect revisited the “most hated woman in America,” actress Robin Givens. If you don’t know the story: In 1988, Givens and her husband, Mike Tyson, gave a television interview to Barbara Walters, addressing persistent tabloid rumors that their marriage was violent. In a stunningly honest moment, sitting next to Tyson, Givens admitted that her husband's abuse tormented her. But Givens’ honesty about her violent marriage to Mike Tyson wasn’t met by massive public empathy for her. Instead, she was vilified—even as additional evidence of his abuse emerged. (Givens ultimately endured, filing for divorce and rebuilding her life despite the vitriol.) In a comprehensive two-episode story, hosts Susie Banikarim and Jessica Bennett examine the cruel public reaction and what it teaches us about America’s misunderstanding of domestic violence at that time; plus, guest Dr. Salamishah Tillet weighs in on what happens when a Black woman comes forward about her abuse.   CLICK THE LINK ABOVE TO GET YOUR UNIQUE SHARE CODE TO SEND TO A FEW FRIENDS. IF FIVE OF THEM SIGN UP FOR THIS NEWSLETTER, YOU GET A METEOR TOTE! ALREADY HAVE A CODE BUT CAN'T FIND IT? NO WORRIES, IT'S WAITING FOR YOU DOWN BELOW ⬇️

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

An "Education Crisis" in Afghanistan

December 7, 2023 Evening, Meteor readers, Did y’all see who TIME voted person of the year? Not to sound like a hipster, but she has been my person of the year since 2012 when the spirit first moved me to jump up on a coffee table and jam out to a burned copy of RED my friend gave me. (Thank you, Brittany, for showing me the light all those years ago.)  In today’s newsletter, we learn of a new crisis unfolding in Afghanistan. Plus, a little unsportswomanlike gloating, and our weekend reading list and a special feature on an inspiring young activist. Balancing it all, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONLost boys: Since the Taliban’s return to power in 2021, the harrowing conditions faced by women and girls in Afghanistan, including their loss of access to education, have been widely shared. But a new report from Human Rights Watch is shedding light on a new group of victims who may have been overlooked: school-age boys. The report has discovered an “alarming deterioration in boys’ access to education” —what HRW describes as an education crisis that could create a “lost generation.” Before the Taliban’s return, most schoolteachers were women; now that they’re barred from teaching, boys are attending classes led by unqualified male teachers, and in some cases, there are no teachers at all. One student who spoke with the researchers said, “The newly hired teachers have highly aggressive behavior toward the students, so the school environment is full of fear.” The report found that many students have stopped going to school altogether to avoid the sharp uptick in corporal punishment. Another student recounted to HRW that he had been whipped on his feet during a morning assembly and had his head shaved in front of his classmates because his hairstyle was “too Western.” A common thread among all the students interviewed is how deeply they feel the absence of the women who once taught them—including those with specialization in subjects like physics and biology, subjects that are no longer being taught in some schools because of a lack of qualified educators. The long-term effects of the education crisis, coupled with Afghanistan’s current economic crisis, will reverberate for generations. When boys and girls are denied access to education, they are more likely to experience heightened rates of discrimination, poverty, and violence. The future of an entire nation is being determined at this very moment, and unless the Taliban can be convinced to function in their country’s best interests, it will be a dark one indeed. AND:

MORALES (CENTER) SURROUNDED BY FELLOW SURVIVORS AND SUPPORTERS IN HER YOUTH NETWORK. (PHOTO COURTESY OF ABRIANNA MORALES)

TRINITY RODMAN STRIKING A WINNING POSE AT TRAINING CAMP. (IMAGE BY BRAD SMITH VIA GETTY IMAGES)  WEEKEND READING 📚

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

32,000 more births

November 30, 2023 Darling Meteor readers, Exciting news! If you click the button below, you’ll get your first annual Meteor Wrapped highlighting how much time you spent reading, what you clicked, and which Meteor events were your favorite. Just kidding! We don’t jive with creepy algorithms that put all your business out there (as entertaining as it is to see what everyone’s been listening to). In today’s newsletter, we check in with the abortion lawsuit in Texas, see dead things come back to life, and share our long reads for the weekend. Don’t need a Wrapped to know I only listened to Taylor, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON32,000 more births: On Tuesday, the Texas Supreme Court heard testimony from some of the 22 plaintiffs in a lawsuit arguing that the medical exceptions in Texas’s abortion ban are too narrow to protect women with complicated or nonviable pregnancies. The testimonies, from women whose lives were threatened by the denial of an abortion, ranged from horrific to unspeakable: last-minute travel plans after heartbreaking ultrasounds; sepsis; purple limbs from severe blood clots; and giving birth to a fetus missing parts of its skull. Writer Jessica Valenti pointed out on Xwitter that when asked by a judge if acrania (the condition that prevents the skull from fully forming) qualifies as an exception to the state’s abortion ban, the lawyer representing Texas admitted she didn’t know what it was. Yet another reason why non-doctors shouldn’t have final say over medical decisions. While some of the lawsuit’s plaintiffs were eventually able to obtain abortions, a new data analysis from the Institute of Labor and Economics sheds light on pregnant people who weren’t. The data estimates that a “significant minority”—between one-fifth and one-fourth—of women living in ban states who may have otherwise gotten an abortion did not get one. That means that in the first six months of this year, 32,000 more people than were expected based on past trends gave birth in those states. One of the authors of the paper says this reflects an “inequality story”: Women in their 20s and Black and Latine women—all of whom tend to be lower-income and are less likely to have the resources to travel—were disproportionately among those who gave birth. Ultimately, this study paints a far broader picture of who is affected by abortion bans than the Texas lawsuit is able to. The stories from the Texas plaintiffs—most of whom are white, married, and wanted to be pregnant before they were faced with medical emergencies—are terrible and dehumanizing, and demand justice. But if you widen the lens, you find a number of invisible victims, who may or may not fit the “good victim” stereotype. People of color are most affected by bans like the one in Texas (where the population is 40% Latine) and yet they remain underrepresented. Perhaps some of those 32,000 pregnant people were also diagnosed with fetal abnormalities—but the rest of them likely would have sought abortions for all kinds of individual reasons. Those reasons don’t matter. The right to bodily autonomy is not conditional; we have to be in it for every last person. AND:

JUST CLICK THE LINK ABOVE TO GET YOUR UNIQUE SHARE CODE TO SEND TO FRIENDS. IF FIVE OF THEM SIGN UP, WE'LL SEND YOU A METEOR TOTE! ALREADY HAVE A CODE BUT CAN'T FIND IT? NO WORRIES, IT'S WAITING FOR YOU DOWN BELOW. ⬇️

WEEKEND READING 📚

Correction: An earlier version of this piece stated that the students in Vermont had been killed instead of injured. We regret the error.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their unique share code or snag your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

Who gets to be called "child"

November 28, 2023 Salutations, Meteor readers, If you’re reading this, it’s time to toss out your Thanksgiving leftovers. I’m sure it all still tastes great, but is five-day-old potato salad really worth the risk to your gut health? In today’s newsletter, we look at the media’s coverage of the temporary truce in Gaza, a staggering report out of Puerto Rico, and as much good news as we can muster. Clearing the fridge, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONWar of Words: What do you call a 13-year-old taken from their home and held against their will by an armed group? Well, it depends. After more than a month of siege warfare, a humanitarian pause was established between Hamas and the Israeli government. As part of this pause, each group agreed to an exchange of hostages and transport of aid into Gaza, the first positive thing that’s happened in weeks. While Israeli children have been accurately described as “child hostages,” Palestinian children captured by the IDF and held for years without trial are being referred to as “detainees,” “minors,” or “prisoners under the age of 18,” which is a lot of words to avoid saying “children.” (Keep in mind that many of the people Israel released have not been tried or convicted of any crimes and include teenagers who were arrested years ago without formal charges.) As the Gazan activist Bisan asked in a social media post last week, “Are our children less children than theirs?”  A 17-YEAR-OLD RELEASED FROM ISRAELI JAIL REUNITES WITH HIS FAMILY. (PHOTO BY SAEED QAQ/ANADOLU VIA GETTY IMAGES) The choice to use such varying descriptors for children is not unique to the current news cycle. We can see it in the way Black boys routinely face “adultification” in the media: Michael Brown wasn’t just a teenager shot by a cop; he was “no angel.” Children captured at the U.S. southern borders aren’t innocents held and transported against their will; they’re “detained migrant minors.” White children and teens, on the other hand, are often described in terms that elevate their youth and victimhood—sometimes even if they’re the ones committing the crimes. They’re not terrorists; they’re troubled; they’re mentally ill; they’re “volunteers.” It should not need saying: Both Israeli and Palestinian children are victims of horrific violence. No child asks to be born in an oppressed territory or to live under an oppressive government. And all children deserve accurate, thoughtful, and fair reporting from our news institutions. As James Baldwin famously wrote in The Nation in 1980: "The children are always ours, every single one of them, all over the globe; and I am beginning to suspect that whoever is incapable of recognizing this may be incapable of morality." AND:

TELL ME SOMETHIN’ GOOD

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

The Evolution of Momfluencing

NEWS

Reflections on the “mamasphere,” 15 years in

BY KATHRYN JEZER-MORTON

I recently went to the theater to see Killers of the Flower Moon, a story of genocidal greed set in Osage County, OK. Its lengthy runtime gave me ample opportunity to think about The Pioneer Woman, one of the internet’s original superstar mommybloggers. A dozen years before Martin Scorsese’s film, Ree Drummond, aka the titular Pioneer Woman, had been responsible for putting her small town of Pawhuska, OK on the pop cultural map.

I haven’t read Drummond’s writing in years. But around 2007, in the early days of mommyblogging, I read everything she wrote, and I wasn’t even a parent yet. She was irresistible—zany and folksy, and her recipes came out well. (I never understood coffee cake until I made this one, the best I’ve ever had.) She took great pictures before most bloggers had the tools to do that. She let you into her home in a way that felt both sincere and idealized—an elusive quality that sat lightly between “unfiltered” and “fake.”

But 16 years later, momfluencing looks nothing like what Ree Drummond helped create. For her part, she’s outsourced almost all the writing on her site, where she’s now eerily referred to in the third person. She runs a massive lifestyle empire that spans national retail, television, and businesses she runs in Pawhuska. She has realized a common dream among content creators: to leverage online fame into tangible sustenance.

The “mamasphere,” as those of us who study this space call it, has dramatically evolved in the past decade, reflecting changes not just in how we consume content, but in how we understand what motherhood is. Momfluencers used to propose a fantasy of domestic harmony, but even for juggernauts of the genre like Ree Drummond, the real world has found its way into the space, and it’s made representing the cute and cozy moments of family life more complex than it used to be. First of all, real life has intervened: early bloggers like Natalie Jean of Nat the Fat Rat and Jill Smokler of Scary Mommy have since left the space due to burnout and personal turmoil. Heather Armstrong, one of the first great talents to emerge from mommyblogging, openly struggled with depression and took her own life earlier this year.

Meanwhile, audiences have gotten bored of picture-perfect content. We expect something very hard to pull off: compelling storytelling about real-life struggles that’s presented beautifully, by someone who could be our friend. Since I began my doctoral research in 2017 about how momfluencers create easily consumable family stories, the mamasphere has fragmented into myriad niches: tradwives, Christian quiverfull families, crunchy moms, neoliberal supermoms, fashion moms, proudly basic goofy moms, mental health advocate moms, party moms, and mom-humor meme accounts. Despite TikTok’s massive influence, Instagram remains the power platform for momfluencers, whiteness remains the dominant racial regime, and hetero remains the default sexuality.

Of all the niches, the freshest and most compelling are the momfluencers who create meta-commentary about momfluencing itself—a phenomenon that could only exist in a genre that has reached a certain level of historical maturity. Jane Williamson is a standout, using physical comedy to send up the tightly wound world of Mormon moms from Utah. She satirizes the rabid urge to execute the perfect fall decor and feuds with “Jessica,” a fictional fellow mom and nemesis.

There’s also Ceci Kane, who makes TikTok parodies of Facebook mom groups, critiquing the profoundly dysfunctional social environments that arise when isolation, anxiety, and boredom converge in online spaces. Lex Delarosa posts scenes of life as a “traditional” homemaker, without any of the elbow grease and struggle that have defined homemaking for most of history. Her videos are mostly straightfaced and unsettling, but occasionally she lapses into arch humor, leaving her audience laughing in bewilderment. In response to a video of her hand-churning butter in her kitchen, someone commented, “Ma’am, this Stepford satire be (chef’s kiss).” No one knows for sure whether Delarosa is a troll, or just someone with a blistering streak of self-awareness—which makes her all the more fascinating as an online persona.

Meanwhile, the archetypal Wine Mom, a relic of a pre-pandemic, pre-Trump world where jokes about moms and alcohol landed as somehow both transgressive and wholesome, has faded into the margins. According to Tara Clark, the creator of motherhood humor account @modernmomprobs, that kind of humor represents the past, as does what she calls “inept husband humor.”

“People don’t even touch that anymore, since the pandemic, when we began really talking a lot more about the invisible load of motherhood,” she says. “It’s just not funny anymore.” Wine moms have fallen out of fashion because of the popularity of sobriety, and the pandemic’s influence on conversations about addiction. Joking about mothers drinking wine or clueless husbands doing everything wrong once felt defiant and important, but now it just seems redundant and, at worst, sad.

The pandemic unseated aspirational content as the pinnacle of momfluencer discourse, and altered the tone of the mamasphere permanently. What has replaced it as a reliable source of engagement is what many creators call “vulnerable content.”

Jessica Turner has been a full-time content creator for two years. She’s an expert in earning income from affiliate links; her original content was upbeat and vanilla, featuring deals on clothing and household goods offered by major brands like Target and Walmart. But during the pandemic, her husband came out as gay and her marriage ended, and buoyed by the shift in tone that was legible across the mamasphere, she shared her story. “We needed to boldly be honest with ourselves,” she wrote on “the shortest and darkest day of the year,” the winter solstice. “A mixed-orientation marriage could not work.”

Turner’s audience broke the hallowed 100k mark during that time, in part thanks to her willingness to be open about her marriage’s evolution. “Certainly if you want to get into metrics, I’ve found that those types of vulnerable, honest posts, whether it’s the grief of my marriage ending, or navigating dating, or exploring my own worthiness – those posts tend to do really well,” she said. “It stops someone’s scroll, to see vulnerability and authenticity.” (She’s since lost some followers, after posting about supporting gun control after a school shooting in Nashville.)

There’s a financial incentive to all that soul-baring. Back in the early 2010s, when Ree Drummond had me and my fellow office-bound young women in a chokehold with her accounts of cooking lunch for her ranch hands, it seemed like momfluencing was a gig that any cheerful mom with a camera could make a go of. But like every unregulated industry, it’s gotten harder to make a living at it. While her income from affiliate linking and other brand partnerships is higher than it’s ever been (in the mid six-figures) Turner admits that it takes serious expertise and focus to earn a living as a momfluencer today. “You have to be a savvy business person for it to be lucrative, or you have to have a massive, massive platform.”

As the barrier to entry rises, and the demands on one’s willingness to disclose sensitive details become relentless, it’s worth asking: Who will opt into this hustle, under these terms? So far it appears to be a new generation of content creators that are primed for competition, strategy, and shape-shifting, rather than wholesome family storytelling.

The work of motherhood itself probably hasn’t changed much in the last 15 years, but the cultural conversation about it has become unrecognizable. The labor of it, and the reality of what our society requires of mothers, can no longer be easily concealed from view without becoming a potent political symbol. We aren’t satisfied with fantasies; we want to see “real life,” only idealized. We expect to be entertained while also feeling seen; we want momfluencers to be better-groomed versions of ourselves.

It’s a lot to ask of a random stranger. All we expected from Ree Drummond in 2010 was to take step-by-step pictures of her recipes and crack jokes about her love of butter. Nowadays, Drummond would need to double-down on being “trad,” or disclose more suffering, or perhaps simply have a larger family. As an audience, we have grown accustomed to a nearly impossible standard. And young momfluencers have no choice but to keep up.

Kathryn Jezer-Morton is a writer in Montreal. She writes Brooding, a biweekly newsletter about contemporary family life, for The Cut.

Kathryn Jezer-Morton is a writer in Montreal. She writes Brooding, a biweekly newsletter about contemporary family life, for The Cut.

Why Do Men Love Telling Women to Have Babies?

|

No images? Click here  November 2, 2023 Hey, Meteor readers, Next Tuesday is Election Day! If you haven’t already, make sure you know your polling place and have a plan to vote, even if the lines are massive. We cannot say it enough: Local elections matter. In today’s newsletter we’re talking about babies, mourning two feminist leaders, and sharing some weekend reading. Researching school board candidates, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONThe birth economy: During the opening of China’s National Women’s Congress last month, President Xi Jinping laid out a comprehensive and innovative plan for reviving China’s economy: Women, please get married and have babies. “We should actively foster a new type of marriage and childbearing culture,” he said, making no mention of women who work outside the home (and, presumably, have something to contribute to the economy themselves). In the face of economic decline and a slowly shrinking population, Xi has turned to a well-worn reactionary directive currently enjoying a revival in the U.S., too: ask women to stay home and raise the next generation of workers rather than find those women jobs and childcare. Despite its name, the Women’s Congress is not a legislative body but an event that occurs every five years to discuss women’s issues. And who gets invited to this prestigious event? China’s predominantly male National People’s Congress, comprised of delegates from various regions. (Their gender ratio is better than the Politboro, Xi’s executive policymaking body, where there are exactly zero women.) During his speech, Xi urged his audience to “tell good stories about family traditions and guide women to play their unique role in carrying forward the traditional virtues of the Chinese nation.” What a poetic way to tell half the population to shut up about their careers and reproduce.  PRESIDENT XI JINPING AT THE OPENING OF THE 13TH NATIONAL WOMEN'S CONGRESS. (IMAGE BY XIE HUANCHI VIA GETTY IMAGES) Speaking of babies: Meanwhile, over in America, conservatives who are badgering women to have babies are coming across more tone-deaf than usual, considering that those babies are dying at a higher rate than they have in 20 years. In the United States, which has the highest infant and maternal mortality rates of any high-income country in the world, deaths before a child’s first birthday have significantly increased this year, per a new report by the National Center for Health Statistics. For every 1,000 births in America last year, 5.6 babies died within their first months of life. While Black infants still have the highest mortality rate in the country, the year-over-year increase was sharpest for Native and white communities. Experts can’t agree on what’s contributing to the rise in deaths, but two possible factors are the COVID pandemic and the fall of Roe, both of which fundamentally changed how Americans sought out and received medical care. Dr. Tracey Wilkinson, an associate professor of pediatrics in Indiana, told NBC News, “Anybody who’s in the reproductive health space could and did warn that this is the type of data we were going to start seeing when we took away the federal protections to abortion access.” AND:

MAY THEIR MEMORY BE A BLESSING

WE'RE GIVING AWAY SOMETHING EXTRA SPECIAL THIS MONTH! FOR EVERY FRIEND THAT SIGNS UP FOR THIS NEWSLETTER USING YOUR ▶️ UNIQUE SHARE CODE ◀️ YOU'LL BE ENTERED INTO A DRAWING TO WIN TWO FREE TICKETS TO MEET THE MOMENT AT THE BROOKLYN MUSEUM DON'T HAVE A CODE? GET ONE HERE!  WEEKEND READING 📚On grief: The videos and photos of the carnage in Gaza are crushing to look at. But as my former colleague Samer Kalaf writes, “Sharing these videos feels like the only way to acknowledge these killings in a moment where many perceive them only as numbers in a news article.” (Defector) On hindsight: Rep. Barbara Lee famously voted against what would later become the ‘00s’ endless war on terror. She offers her thoughts on the value of restraint in the face of devastating violence. (Washington Post) On the happiest place on Earth: Writer Alana Levinson spends a spooky, surreal day at Disneyland with former Playboy bunny-turned-author and TikTok star Holly Madison. (Bustle)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

A purge in Ohio

|

No images? Click here  October 31, 2023 Happy Halloween, Meteor readers, I’ve never been much of a costume girlie. I prefer Dia de los Muertos, which is celebrated in the days after Halloween. I love the idea of making the veil between the living and those who’ve crossed over a bit thinner. So remember to put out a candle and a little treat for your loved ones or any other spirits you’re welcoming. And if there are some ghosts you’re trying to avoid? Burn a little sage, name the ghost, and say aloud that they aren’t welcome. You can thank me later.  In today’s newsletter, we take a look at GOP tomfoolery in Ohio, the arrest of an Iranian hero, and an engagement announcement. Summoning spirits, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONThe Purge: Nearly 27,000 people just lost the ability to vote in Ohio. How does that happen, exactly? It’s routine to maintain the list of registered voters by removing those who change their names or have moved. But in the last decade, since a 2013 Supreme Court case gutted the Voting Rights Act of 1965, irresponsible purges are on the rise—and often come with a political motivation. This Ohio purge is particularly suspect because of its timing and, more to the point, because of what's on the ballot next week. Before they’re removed, voters are required to receive notification about the pending risk. But since those notifications can easily slip under the radar, it’s customary not to carry out a purge so close to an election. The fact that Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose scheduled this purge less than a week before Election Day has raised suspicions among his colleagues—especially because, just this August, LaRose delayed a purge until after a special election that included a GOP-backed measure meant to make it tougher to pass constitutional amendments. Which brings us to the heart of the issue: What exactly is LaRose preventing some Ohioans from voting on next week? A few things, but the big fish on the ballot is Issue 1, a measure that would amend the state constitution and “prevent the state from banning access to abortion, contraception, miscarriage care and other reproductive decisions.” LaRose knows the odds are stacked against him. Similar elections putting abortion on the ballot have resulted in a spate of pro-choice victories, even in conservative states like Kansas, Kentucky, and Montana. The GOP is fully aware that the majority of Americans support abortion access, and voter suppression is the only way to get around that inconvenient fact. (For a party that claims to hate government overreach, they’re giving extreme reach.) If Issue 1 does go on to fail by less than 27,000 votes next Tuesday, the purge may have been successful, and LaRose will have laid out a blueprint for other anti-abortion Secretaries of State looking to change the outcome of elections. These kinds of tactics are a reminder of just how much extremists rely on sowing confusion and making voting as difficult as possible. Don’t let them. AND:

Demonstrators rally outside the U.S. Capitol demanding a cease fire in Gaza on October 18. (Image by Chip Somodevilla via Getty Images)

WE'RE GIVING AWAY SOMETHING EXTRA SPECIAL THIS MONTH! FOR EVERY FRIEND THAT SIGNS UP FOR THIS NEWSLETTER USING YOUR UNIQUE SHARE CODE BELOW YOU'LL BE ENTERED INTO A DRAWING TO WIN TWO FREE TICKETS TO MEET THE MOMENT AT THE BROOKLYN MUSEUM DON'T HAVE A CODE? GET ONE HERE!  ICYMIDidn’t make it to Work Shift? We’ve got you covered! Enjoy this panel discussion featuring two HR execs who are letting us non-HR folk know what goes on behind the scenes—and how they're putting the “human” back into human resources. SPONSORED BY:  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

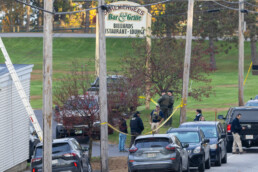

"Why do people do this?"

|

No images? Click here Good evening, Meteor readers, As we amble our way towards November (it’s RIGHT there), I am thinking of entering a season of gratitude. With the news awash with tragedy—the mass shooting in Maine, the devastation of Hurricane Otis in Acapulco, and the continuing crises in Gaza and Israel—I am more aware than ever of how often I take for granted life’s small pleasant surprises. Let’s all choose to be better about that. In today’s newsletter we look at the inadequate gun laws that made way for the Maine shooting, share our weekend reading, and hear from one of the women who first blew the whistle on AI’s biased ways. With love, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON THE BAR WHERE PART OF WEDNESDAY'S MASS SHOOTING TOOK PLACE. (IMAGE BY SCOTT EISEN VIA GETTY IMAGES) Lewiston, Maine: It started in a bowling alley on Wednesday night. Officials say that around 7 p.m., a gunman entered Sparetime Recreation and started firing rounds from an “assault-style weapon.” He eventually fled the scene and drove to a local bar to continue the shooting spree. So far, 18 people have been confirmed dead, with 13 injured. One of the wounded, a 10-year-old named Zoey, who was there with her youth bowling league, told a local news station, “I had never thought I’d grow up and get a bullet in my leg. And it’s just like, why? Why do people do this?” The simplest answer to Zoey’s question is: because they can. The suspected gunman, Robert Card, is a firearms instructor and a U.S. Army Reservist. As early as this summer, military officials had “concerns” about Card, and later reported him for erratic behavior while supporting summer training for cadets at West Point. Card was later admitted to a mental health facility, where he claimed he’d been “hearing voices and threats to shoot up” West Point. Despite all of this, Card still had access to firearms. That’s because in Maine—where gun laws are some of the most obscenely lax in the country—just about anyone can legally acquire a firearm. There are weak background check laws, no waiting periods, and no red flag laws, which prohibit gun purchases or possession for anybody who shows signs of being a threat to themselves or others. (Hearing voices and threats to shoot up West Point would count.) Not only that, Maine has had a “permitless carry law” since 2015. This means that any person over the age of 21 “or at least 18 and active duty or honorably discharged military” who owns a gun can carry “loaded, concealed handguns in public without a permit or background checks.” It should not take a mass shooting to enact the most basic gun safety laws. It’s too late for the 18 victims and their families, but it isn’t too late for Zoey, or the rest of us. You can learn more about safety initiatives in Maine from The Maine Gun Safety Coalition and check the laws in your state at Everytown for Gun Safety. AND:

“The Past Dwells in our Datasets”Can AI ever be unbiased? MIT scholar Dr. Joy Buolamwini has some answersBY REBECCA CARROLL  (IMAGE BY PARAS GRIFFIN VIA GETTY IMAGES) In the celebrated Steven Spielberg movie A.I., set in the 22nd century, scientists create an android boy capable of experiencing human emotions. The film (and its all-white cast) try hard to convince us that at its best, artificial intelligence can learn to love. That was 2001. More than 20 years later, we’re discovering that AI—which now mostly takes the form of computer programs rather than robots—often actually reflects real people’s worst biases. And those embedded prejudices are doing a lot of harm, argues computer scientist, digital activist, and “poet of code” Dr. Joy Buolamwini in her new book, Unmasking AI: My Mission to Protect What is Human in the World. Born in Edmonton, Canada, Dr. Buolamwini spent her early years in Ghana before moving with her artist mother and scientist father to Mississippi when she was four. Just five years later, she saw an MIT-made robot called Kismet on a PBS science program—and decided on the spot that she was going to attend MIT to study robotics. But, once at MIT, she quickly realized her calling was much bigger. As she learned about the ways racial, gender and ableist biases had crept into facial recognition technology, she launched the Algorithmic Justice League, an organization that uses art and policy to advocate for equitable AI systems. I talked to Dr. Buolamwini about not just the harm but the potential of AI. Rebecca Carroll: You write that AI developers promise that AI will “overcome human limitations”—what does that mean exactly? Dr. Joy Buolamwini: AI is presented as enabling humans to be more efficient, more productive, and help overcome human limitations. For example, some AI tools for hiring have been presented as an alternative to human decision-makers who we know can be biased. The problem is AI tools are often created with datasets that reflect past decisions. So AI tools trained on past hiring decisions will reflect the preference and prejudice of the past and make them into current technologies. Amazon found this out when it attempted to make a hiring tool that was shown to discriminate against women. They ended up getting rid of the tool because even after they tried to address the bias, it still favored men. I think it is easy to assume technology will be more neutral than human because technical systems are mathematically based, but it is important to remember that the past dwells in our datasets. You talk in the book about the “arbiters of ground truth”—the idea that data or statistics offered through empirical evidence is the only real truth. How does AI complicate that view? The more I do work on AI, the more I see the importance of storytelling. [One’s] lived experience matters. As a graduate student, I was reading about so many AI advances, yet I found myself coding in a white mask to have a computer see my face. I recorded that experience as something I call a counter-demo. Like a counter-narrative, a counter-demo captures an experience that challenges master narratives of who or what is considered normal or worthy, and in this case master narratives about technological advances. My spoken word poem, “AI, Ain’t I a Woman?”, which is also a test of various AI systems, contains many counter-demos of tech companies failing [to identify] the faces of iconic women of color. It challenges the narrative of tech superiority when we see AI failing [to recognize] the faces of Oprah Winfrey, Michele Obama, Serena Williams, and more. I smiled when I read about your first meeting with Timnit Gebru, where you noted that you both wore your hair natural—itself the subject of centuries-long racial profiling and discrimination. Are there specific policies you’re seeking to put into place to help fight against “the coded gaze”? I dropped a few hair references throughout the book, and I am so glad you noticed! I think governments around the world can learn from the EU AI act, which puts a specific ban on the live use of facial recognition technologies in public places. We can also stop police from using facial recognition for investigative leads, as this dangerous use of AI has already led to false arrests, including the arrest of Porcha Woodruff. AI-powered facial recognition misidentification led to her false arrest for carjacking by the Detroit police department. She was eight months pregnant sitting in a holding cell and having contractions. Three years before Porcha’s arrest, Robert Williams was falsely arrested for theft in front of his two young daughters by the same Detroit police department. Despite ample evidence of racial bias in facial recognition technologies, we still live in a world where preventable AI discrimination is allowed. The excoded (those harmed by AI) include even more people falsely arrested due to AI, like Michael Oliver, Nijeer Parks, Randal Reid, and others whose names may never make headlines, but whose lives matter all the same. You call yourself “the poet of code”—is that a nod to the fact that you are, as you share in the book, the daughter of art and science? Absolutely. Growing up, I saw art and science as companions just like my parents. I also see the role of a poet as showing us perspectives that may be marginalized, ignored, or largely unseen. In my poetic work with evocative audits, I use the spoken and written word to humanize AI harms. Poetry takes me to places research papers cannot go. When you were at MIT, you took a class with the Harvard professor Karen Brennan, who posed the question to you and the other students: “What will you do with your privilege?” How would you answer that same question today? I answer it by using my platform to give voice to feelings and perspectives that might otherwise be suppressed. Here is a recent poem I wrote called Angels Awake, on recent man-made and natural disasters: Heart aching, tears breaking, cycles of pain continue. Spine snapped; hope broke... The earth trembling too. Geography and circumstance shaping the fate of precious souls. Today, I walked through beautiful gardens and sat in chairs of opportunity. My life blossoming as the petals of others fade. How can I not be compelled to use every privilege given to offer healing to deepening wounds? Yet, where do we start when the tsunami of history overwhelms? Seismic shifts are centuries in the making. As the night carries on, I remain awake and agitated, grateful to at least be alive to take another breath… A gift lost by many others far too soon. The aftershocks are coming. Where be our better angels now? This interview has been slightly edited and condensed for clarity.  Rebecca Carroll is a writer, cultural critic, and podcast creator/host. Her writing has been published widely, and she is the author of several books, including her recent memoir, Surviving the White Gaze. Rebecca is Editor at Large for The Meteor.  WEEKEND READS 📚On the river and the sea: A slogan of Palestinian freedom is once again under fire for potentially being antisemitic despite many, including this scholar in 2018, explaining its origins. (Forward) On romance: Who would have thought the savior of Bachelor Nation would be this guy? (Vulture) On TV: Not in the mood to read? It happens. The HBO documentary No Accident, which follows a lawsuit brought by those injured while counter-protesting the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, is both riveting and informative.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their unique share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()