"They Don't Look at Us as Human Beings"

Lead plaintiff Amanda Zurawski on the Texas Supreme Court’s decision to uphold a ban that almost killed her—and why she’s planning to run for office herself

BY CINDI LEIVE

We’ve grown accustomed to courts acting coldly, but last Friday’s Texas Supreme Court decision seemed especially and brutally devoid of compassion. In Zurawski v. State of Texas, the court had heard from 20 women who had been denied abortion care when experiencing pregnancy complications—women who had hemorrhaged, been forced to carry babies without skulls, and nearly died. And yet, the justices still ruled not to change or amend Texas’s abortion ban, which has forced doctors to deny patients vital medical care out of fear of prosecution. (What this says about the state’s regard for the vastly greater number of people who need abortions for less “medically necessary” reasons—such as, you know, not wanting to be pregnant anymore—is a story for another time.)

Over the weekend, I called Amanda Zurawski, the woman who lent her name—and the last year and a half of her life—to the lawsuit. I first met Amanda in the fall of 2022 when a doctor whispered to one of my Meteor colleagues that there was a woman in Austin who’d been through hell and might be willing to share her story. She did, detailing her harrowing experience for the world, but then went on to do much more, testifying before Congress, speaking up for other patients—and taking on her own state’s government.

Cindi Leive: This decision felt like a punch in the face to so many women—but for those of you who testified, and your families, it was so personal. What measure of justice were you and [your husband] Josh expecting? How much was this a surprise to you?

Amanda Zurawski: It wasn't a huge surprise because we know that the Texas Supreme Court is full of conservative Republicans—[all] nine of [the justices] are conservative Republicans. And then, after the ruling in the Kate Cox case [in which the court denied the December 2023 abortion request of a Texas woman whose fetus had no chance of survival], that was a signal of how our case was going to go. So we had time to prepare for a loss.

What we weren't expecting, and what we were really surprised by, was the way that they wrote the decision—that they literally wrote out most of the plaintiffs by not even using their name. [Only three patients and two doctors were referred to by name in the ruling.] And that felt unnecessarily cruel and offensive…To me, it means they don't care about us and they don't look at us as human beings. They don't care about our trauma, our grief, our loss. They don't want to acknowledge us. Because as long as they can ignore us and pretend like we don't exist—just like my Senators [Ted Cruz and John Cornyn] did when I testified in front of Congress—they can pretend like the problem isn't real.

We did a press call right after the ruling came out, and there were 11 plaintiffs that could join. And seeing their faces and hearing their voices and how heartbroken they were—that was really gutting.

You said that that was the hardest part for you. Why?

I want to acknowledge my name was used in the Supreme Court's decision. They did acknowledge what happened to me personally, and they didn't for anyone else. And that feels very unfair and very unjust. And I also feel a little bit like…people were counting on me, I think, because I was the first one to file, because it was my name on the suit…I do feel a little bit like people were depending on me, and I feel a little bit like I let them down.

You said on Friday, “We will continue to fight.” Tell me how.

Well, I don't think our lawsuit can do much more. People keep asking me if it's going to go to the U.S. Supreme Court, and I want to make it very clear that…likely, this is the end. But we can keep fighting in other ways. Personally, I will continue to campaign to get people to vote for pro-choice candidates. We can continue to share our own stories and to share other people's stories. We can donate our time and our money to abortion providers and organizations.

And did you say that some of the Texas Supreme Court justices are up for reelection?

Yes! There are three up for reelection [Jimmy Blacklock, John Devine, and Jane Bland]. I think we know now very clearly how they feel about…a woman's right to choose, so I'm really hoping that we can get the word out before November and not get them reelected. It feels really good to be able to say that so clearly, because for a year and a half I couldn't, because we had an ongoing lawsuit. [Now] I'm like, let's light some fires.

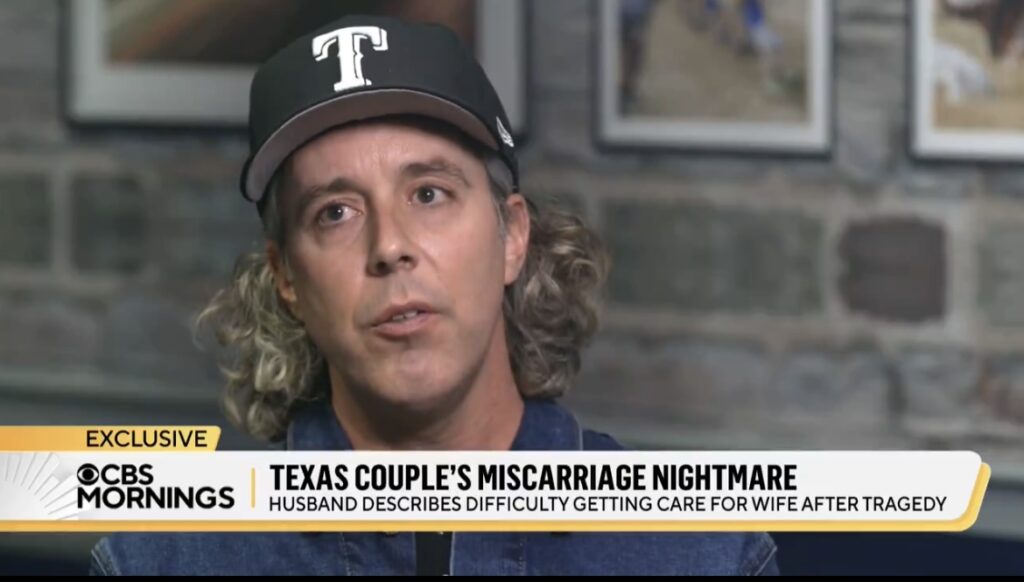

I’ve been thinking about what’s happened in Texas since you first filed your lawsuit. You were the first [plaintiff], and then there were five women, and then 20. And I don't know if you saw this thread, but just two weeks ago, Ryan Hamilton, a musician and DJ, tweeted that his wife, who had been pregnant with their second child, was denied abortion care in a very similar situation to yours. Despite the baby no longer having a heartbeat, she was repeatedly sent home. She lost so much blood that he found her unconscious on the bathroom floor. She almost died. This happened in Texas two weeks ago. How does it feel knowing that while the Supreme Court is making this decision, claiming that doctors are able to do the right thing [under existing Texas law], the number of women who have been exactly where you were continues to climb?

That story makes me sick to my stomach. And it's going to keep happening, because lawmakers aren't doing anything to fix it. It's infuriating that the Supreme Court of Texas had the opportunity to fix this—had the opportunity to make things better—and they did nothing. And when the Supreme Court says, “Doctors can practice medicine, this isn't a problem, the law is clear”—clearly that's not the case! Listen to our stories. Listen to what's happening to us. Listen to doctors. They refuse to hear us, and I don't know what it's going to take for them to wake up and realize that people are dying because of this. Or if they haven't yet, they're going to.

There's an enormous amount of suffering happening in Texas and similar states, and they need to fix it.

Three months ago, when the Alabama Supreme Court was deeming embryos people, you said that you worried that Texas was going to do the same, and that you were going to move your embryos out of state. The irony is incredible: You need IVF because the state's laws impacted your fertility, and now the state is making that path to having a family more difficult. How has that process felt?

It was pretty upsetting, because moving embryos is, as you can imagine, incredibly complicated. It is very expensive. And from my understanding, things don't go wrong very often, but if they do, it's catastrophic—you lose your embryos. As we [were] going through it, I'm like, this is terrifying, because I feel like we're on a ticking clock, because Texas [could] make this decision [to criminalize IVF] any day. By the way, there now is a case about embryonic personhood that the Texas Supreme Court is deciding whether or not to hear…[and] depending on how they rule, it could do the exact same thing that happened in Alabama and threaten IVF access. Fortunately, our [embryos] are now safe, but if Trump is reelected, we're scared that it won't matter where your embryos are, because he'll institute national bans or laws that are going to affect their safety. It's just a really troubling, scary time right now to be trying to plan a family.

Last question—what gives you hope right now? Is there anything?

You know, in our press call, my fellow plaintiff, Dr. Austin Dennard, said that she likes to think that people are good. And I agree with her. I think that most people at their core want to do the right thing. And when we're speaking out about what happened to us, we do see a lot of goodness in most people. And I see the people who are fighting in their communities. I see people who are running for office because they're trying to protect women. And I think there's a lot to be hopeful about. I do think we're going to fix this. It's going to take a lot of work, but we can do it.

You mentioned women running for office. I can't get off the phone without asking you the same question that America Ferrera asked you onstage at our event a year and a half ago. Any further thoughts about you running for office?

Oh, yeah… That is probably going to happen. I've started trying to figure out what office might be a good fit for me. I’ve talked to a lot of different organizations; I’ve talked to a lot of different individuals. I think the next step would be fundraising. But Zurawski ‘26 is probably something you’ll see.

Zurawski 2026. Amazing. We’ll leave it there.

The plaintiffs in the case are: Patients Amanda Zurawski, Lauren Miller, Lauren Hall, Anna Zargarian, Ashley Brandt, Kylie Beaton, Jessica Bernardo, Samantha Casiano, Austin Dennard, D.O., Taylor Edwards, Kiersten Hogan, Lauren Van Vleet, Elizabeth Weller, Kristen Anaya, Kaitlyn Kash, D. Aylen, Kimberly Manzano, Danielle Mathisen, M.D., Cristina Nuñez, and Amy Coronado; and health care providers Damla Karsan, M.D. and Judy Levison, M.D., M.P.H. Read their stories on Center for Reproductive Rights' site.

Everyone is Having Fun Talking About Drake and Kendrick Lamar

A long-time music critic tackles a darker truth at the core of their beef: the expendability of women’s trauma

By Julianne Escobedo Shepherd

Kendrick Lamar and Drake have spent the better part of the past month in a rap beef, which you might already know if you spend time on social media, where they've been trending for days. The origin of their acrimony is vague—the former collaborators turned on each other around 2013—but this recent round was kicked off in late March with a song called "Like That" from Future and Metro Boomin's latest album, We Don't Trust You, on which Kendrick, guest-rapping, essentially called Drake a poseur and a chicken. That provoked some peripheral fallout, including a Drake diss by Rick Ross coming from the sidelines and a very weak response track by J. Cole, which he later walked back, apologizing to a stadium full of his own fans.

Confused? There is a lot of minutiae here and even more menergy; all of this feels like a desperate display of testosterone in an era when women rappers are finally flourishing. But there are larger issues here that go beyond which rapper has the better flow, and it might not surprise you that women have ended up as collateral damage.

Rap beef is rooted in the Dozens, a traditionally African American game of insults. The Dozens, in turn, influenced the freestyle battles that have flourished since hip-hop's inception, in which two rappers diss each other to flex their superior lyrical talents, not unlike a verbal boxing match. In the Drake versus Kendrick battle, Kendrick is obviously superior; he has a better grasp of the language overall—a skill for which he once won a Pulitzer—and is more capable of varying his writing style. There is a comfortable consensus, too, that he's winning the battle due to how deeply his insults cut, to the point that I keep imagining him as the X-Men character Psylocke, wielding a particularly sharpened psychic knife.

But as far as rap beefs go, this one feels increasingly gnarly. When Kendrick first asserted on "Like That" that respect is better than money or power, implying that Drake had the latter but not the former, it was fairly standard fare. Drake responded with "Push Ups," which dissed Kendrick's star power, and also with "Taylor Made Freestyle," which claimed that Kendrick's releases were being controlled by Taylor Swift. The idea that a man is in servitude to a woman is a pretty standard insult—but in retrospect, it was also an indicator of where this was all going.

Over the course of four more Kendrick songs and two more Drake songs, all released in the short span of seven days, the rappers hit one another with an escalating series of basically criminal accusations. (On Monday evening, a security guard outside Drake's Toronto mansion was shot, though authorities are currently investigating.) Drake accused Kendrick of hiring "a crisis management team to clean up the fact that you beat up your queen." My stomach fell upon hearing it—it's a shocking accusation, especially when it’s brought up so lightly in a rhyme.

But even worse was the fact that Kendrick's response was released only 30 minutes later, and so the accusation of violence barely seemed to register. Besides, Kendrick's barbs were just as nasty: that Drake is a pedophile, has a sick interest in underage girls, and that his record label might, in fact, be a ring of pedophiles. Kendrick suggested that Drake should be locked up alongside Harvey Weinstein, who at this moment is awaiting a new trial after a New York court overturned his rape conviction. Obviously, rapping it doesn’t make it true: As a written art form, a lot of rap lyrics are fantasy or narrative construction—that's part of why it's an infringement of First Amendment rights when those lyrics are used as evidence in trials. But does assuming that these allegations are simply lyrical shivs make them any better? Actually, the idea that women and girls are simply pawns in a brawl implies that neither artist cares too much about their well-being—unless they can be used as a weapon.

And if these accusations have even a kernel of truth to them, they reflect the way the entertainment industry keeps secrets to protect its own (and the way the #MeToo movement barely touched the music industry.) I keep thinking about Megan Thee Stallion, one of the most talented rappers in the U.S., who spent two full years being excoriated by male musicians and internet trolls after she accused Tory Lanez of shooting her in the foot; she was in a desperate enough place that she later rapped about her thoughts of suicide. Before Lanez was convicted in December 2022, even 50 Cent was forced to apologize for his ill-treatment of Megan.

But throughout the case, Drake was one of the worst offenders against Megan, rapping, "This bitch lie 'bout gettin' shots but she still a stallion," one line in a trilogy of Drake albums that seemed to trace his further descent in the darkest crevices of misogyny. (His latest, For All the Dogs, seems at times to just be a list of grievances against women.) As Vulture's Craig Jenkins wrote in a wide-ranging piece about the violence and sex trafficking allegations against superproducer Diddy, "We can’t keep picking and choosing whose abuse we’re willing to buy, turning support for survivors into a contest of whose abusers made the most beloved songs. We can’t let wealthy men treat everyone in the vicinity like chattel."

Megan eventually was able to bite back—her January 2024 diss track "Hiss," which in part takes aim at Drake, is the most listenable of all the songs in this rap beef—but the scars are right there on her album, called Traumazine. The unnamed women in Drake and Kendrick Lamar's beef tracks surely have their own scars, too. While hip-hop battles can sometimes feel like a sport, this one has become increasingly nihilistic. One wonders if either of these men is invested in what they’re saying or can even fathom what’s at stake for the lives of the people they are talking about, real or fictional.

They Waved Her Underwear in Front of a Jury and Called Her a "Slut Puppy"

THEY WAVED HER UNDERWEAR IN FRONT OF A JURY AND CALLED HER A "SLUT PUPPY"

Now Brenda Andrew is on death row, and the Supreme Court could weigh in

BY NEDA TOLOUI-SEMNANI

The U.S. Supreme Court will decide this Friday if it will hear the case of Brenda Andrew, the only woman currently on death row in Oklahoma. The Andrew case is the second Oklahoma capital punishment case vying for the court’s attention this term, and it has potentially far-reaching ramifications—not just for the state, but for the rights of women and queer people everywhere.

The background on the case is this: Andrew, along with James Pavatt, her former partner, were found guilty of first-degree murder in the 2001 shooting death of Andrew’s estranged husband, Rob, but the jury rejected the state’s charge that Andrew would be a “continuing threat to society.” Nonetheless, both Andrew and Pavatt were sentenced to death. Throughout Andrew’s 2004 trial, her sexuality, her dress, her demeanor, and, ultimately, her behavior as a wife, mother, and Christian were dissected and condemned. In an amicus brief filed with the Supreme Court, a former federal judge, 17 law professors, and four domestic violence advocates argue that the Andrew case was rife with gender bias that unfairly prejudiced the jury against her.

“At a time when women’s rights generally are on the chopping block—also the rights of queer people and civil rights of minority communities—we’ve got a case that’s at the extreme end of what it means when we dehumanize these communities when we strip people of their humanity,” says Nathalie Greenfield, a lawyer with the non-profit firm Phillips Black, which filed the writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court on Andrew’s behalf. She argues that if the Supreme Court does not review the case, the justices would sanction using “assumptions, stereotypes, and tropes about people who dare to transgress perceived norms,” especially when it comes to gender, race, and identity.

The trial transcript, for example, reveals that witnesses were encouraged to describe Andrew’s appearance in detail, from her dresses (“very tight, very short, with a lot of cleavage,” said one) to her make-up choices (“gothic”), and also to say whether they thought those choices were appropriate. Prosecutors also waved Andrew’s underwear in front of the jury and called her a “slut puppy,” one of the last things members of the jury heard before they began to deliberate.

“There [were] just so many recorded instances of gendered evidence being presented every single day [of the Andrew trial],” says Greenfield. “And a lot of this was about her appearance and her extramarital affairs. The focus was on the fact that this was a woman who was transgressing gender norms by not being this chaste Christian wife.”

Oklahoma is a particularly deadly state: It has executed 124 people since 1976, when the U.S. lifted its moratorium on capital punishment. (Only Texas has killed more people.) Of these, just three were women—two of whom were prosecuted by district attorney Bob Macy, who is considered the second deadliest prosecutor in United States history. He’s responsible for 54 death sentences—more than any other prosecutor who was practicing law between 1980 and 2001. He resigned in 2001 after evidence of prosecutorial misconduct was found in 18 of those 54 cases, resulting in three exonerations.

However, his shadow still stretches over Oklahoma’s justice system—and Macy’s assistant district attorney and protege, Fern Smith, was a prosecutor in the Andrew case. According to transcripts, Smith repeatedly asked witnesses to describe Andrew’s dress, opine over Andrew’s behavior, and state whether or not Andrew was, in Smith’s words, a “good mother.”

This isn’t the first time a case Smith has prosecuted has been challenged. She has been repeatedly accused of failing to disclose exculpatory evidence—evidence that could be favorable to the defendant—and even of destroying evidence. In fact, she was accused of prosecutorial misconduct by name in the case of Richard Glossip, the other Oklahoma capital punishment case that will be in front of the U.S. Supreme Court this year.

At a time when women’s rights generally are on the chopping block—also the rights of queer people and civil rights of minority communities—we’ve got a case that’s at the extreme end of what it means when we dehumanize these communities when we strip people of their humanity.

The Supreme Court has already delayed deciding whether to hear Andrew’s case twice. Tomorrow, they could do one of three things: agree to hear it, decline to hear it, or “vacate and remand,” which means the Supreme Court could return her case to the appellate court to reconsider without hearing an oral argument.

Since Andrew was sentenced, she has been the sole woman on death row; consequently, she has served the majority of her sentence—more than 16 years—in solitary confinement. According to the United Nations, prolonged solitary confinement, or more than 15 days without meaningful human contact, is defined as torture.

In February 2020, Andrew was moved to the general population, where, according to her lawyers, she thrived. She got a job and joined a quilting circle. In January, two days after her attorneys filed the writ of certiorari with the Supreme Court, Andrew was returned to solitary. She wasn’t given a reason.

“The gender bias is just so finely woven into the trial that you can’t extricate it,” argues Jessica Sutton, another attorney with Phillips Black. “It’s unique in that way. However, the real issue implicates the due process clause of the 14th Amendment. We have to ensure that trials are fundamentally fair. We want to make sure that, for the ultimate punishment, we have a reliable trial, a reliable process, a reliable conviction, and sentencing. What the prosecution did is undermine every aspect of the entire trial.”

Neda Toloui-Semnani is an Emmy-winning journalist and the author of They Said They Wanted Revolution: A Memoir of My Parents.

Christine Blasey Ford, In Her Own Words

April 12, 2024 The author of a new memoir on retaliation, recovery---and the survivors who reached out to herBY CINDI LEIVEFive and a half years ago, psychology professor Christine Blasey Ford raised her right hand before the 21-person Senate Judiciary Committee and became, despite her best attempts otherwise, a public figure. Her testimony that then-Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh had sexually assaulted her when they were both in high school—that he had covered her mouth so violently that “I thought that Brett was accidentally going to kill me” and laughed while doing it—riveted the country in one of those moments that felt like history even as it was happening. On one level, we all know what happened next: Kavanaugh railed angrily, protestors took to the streets, and after a brief delay, he was confirmed while the sitting president mocked Dr. Ford ruthlessly. But what happened next to the woman at the center of the hearings—and what led her to that day? Those are the questions Dr. Ford answers in her new memoir, One Way Back, an account of everything before, during, and after her testimony.  DR. FORD BEING SWORN IN FOR HER TESTIMONY. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) I’ve known Dr. Ford for a few years, and thus have had a glimpse of the dual role she plays in mid-2020s America. To me—and I’m guessing to most of you—she’s a hero, someone who respects the integrity of this country’s highest offices so much that she sacrificed her own privacy, comfort, and security for them. To the radical right, though, she’s a target—so much so that death threats (“I want to see you three feet under, six feet under…” she says) have been a constant in her life, and she’s had to hire security to protect her family. After she appeared alongside Professor Anita Hill on The Meteor’s podcast Because of Anita two years ago, I got a call from a political operative hissing ominously, “She was told to keep her mouth shut.” I’m so happy she hasn’t. Her book is full of secrets and grief and Capitol Hill betrayals, but also sun and surf and heavy metal and the voice of the actual human behind that blue suit and raised right hand. We talked by phone two weeks after her book came out. Cindi Leive: You once told me that when you thought about writing a memoir about testifying, you thought of those kids’ books that can be read two ways—like you read it in one direction, and then turn it upside down and it’s a different story. What were those two ways that you thought about your own experience? Christine Blasey Ford: I think for the first two or three years post-testimony, I was torn between two books I could write: One would be why you must do this, with all the benefits [of coming forward about assault], and the other would be why you should never do this—about all the forces that are working against you, and all of the costs. For a long time, I was in a place of experiencing the retaliation and costs. That's why I chose not to write for so long. I knew that my first attempt would not be helpful to anyone. I think it was at the five-year mark that I began to feel that it was part of history, not part of current events. For me personally, it felt like it was enough in the rearview mirror that I could try to write something that honored that, yeah, this is life-changing, and there was a cost, but there's also a bunch of benefits that you don't really see while you're making the life changes. You and I met through a project focused on the more than 100,000 letters you got after you testified. And I remember you saying at first that you thought to yourself, Why are they writing me? Didn't they see the end of the movie? Meaning—that [Kavanaugh] was confirmed anyway… The first letters I read were [written] during the week of the paused investigation between the hearing and the vote, where [the FBI] was going to supposedly look into things a little deeper and do an extended background check. And those letters were really hopeful—and I felt bad for them considering how it ended [with no extensive investigation and a swift confirmation] because their hopes had been raised. And then, with the letters that came after, I just felt like, “I bet a lot of this mail is people who are feeling sorry for me.” I felt like I had missed a game-winning field goal or made an own goal in a game. [Laughs] But then, when I really looked through the letters…yes, people felt bad for me, but that's not really why they were writing. There was an amazing benefit happening for survivors watching the testimony: They wrote that they were inspired to make more clarified decisions about whether they wanted to come forward or not about their own assault or they wanted to share it with someone else. And I grapple with the fact that all of that came because I didn’t get my way that the hearing be kept private. It was televised, and even though it turned my life upside down, it benefited so many people. Wait, pause on that. You write that you didn’t actually realize it would be televised…you thought, “Maybe it'll be on C-Span, but who the hell watches C-Span?” [Laughs] I mean, I was walking down the hallway like, “Oh, it's a work day. No one's going to watch this. My friends are all really hard workers, and they have class and they have responsibilities. I'll catch them up on it when I get back.”  MILLIONS OF PEOPLE STOPPED TO WATCH DR. FORD'S TESTIMONY. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Cut to me sobbing in front of my television in Brooklyn, along with practically every other woman in the country. Right. During my first break, I really realized the magnitude of people who were watching it because I looked at my phone and had more text messages than I had ever collectively received. “Good job!” “You're doing great!” [Laughs] I was like, “How do they know?” But if it had gone the way you had anticipated—like, one camera for the archives somewhere in a basement—then these 100,000 people wouldn't have been able to make meaning in their own lives…And that process of “meaning-making,” I learned from you, is an actual psychological phenomenon. I didn't understand it until my student at the time—Elizabeth Michael, who's now a doctor of psychology—explained it to me: People change their emotions and cognitions based on hearing or viewing someone else's experience. And I still was in a pretty rough patch in my life, so I wasn't really understanding…so she placed it in the context of television and movies. If you're watching a TV show and you're relating to some character, there's this small shift and identification and validation that's happening about your own thoughts and feelings. It starts to open up something in your own mind to think about. I'm wondering if you want to share a couple of the specific letters that moved you… All of the things that people made by hand or knitted—almost every day, I could wear an item of clothing, whether it's socks or gloves or a shirt or a scarf, or blankets, that people made. The simple thank you’s were beautiful in their own right—and then there were 10-page letters from people sharing what they had been through themselves. And also the offers! Like Otis from Texas, offering his truck for my family to move in, and people from all over the country saying, “You can come stay at our place. We have a cabin!” Like, who would open their door to a stranger? A lot of people, apparently. You’ve said that survivors in their 70s and 80s wrote you to say that they'd never talked about their own experiences before. What was it like to read those letters? I felt for them—and I felt like I could have easily been one of them and gone the rest of my life without really talking about this. I was on a different path once the Supreme Court was in play—I felt the value of that institution was more important than me. But those letters were really hard to read at the beginning. Then I adapted, and I feel like I have a new role, which is to be a recipient of those stories and to honor them. That’s also what happens to me any time I go out in public: People come up to me and want to tell me what happened to them. They’ve identified me as a safe person to speak to about their story. At first, that role was really overwhelming. And now, it's an honor. I'm honored to be that person.  DR. FORD SIGNING HER MEMOIR FOR A READER AT A GATHERING IN LOS ANGELES. (PHOTO BY MAYA JOAN) You and Anita Hill have a lot in common. And you talked about this when you were on the Because of Anita podcast two years ago, but part of your common experience is that in both of your cases, Congress failed to do a full investigation. And in your case, we later learned that the FBI had received 4,500 tips at the time of the hearing and shared them with the White House, at which point nothing happened. First of all, how have you let go of being, like, so damn angry about that? Because it's hard for me to even say those words aloud and not be pissed. That was really quite something. And the public didn't learn about [the failed investigation] until, like, two years after the testimony. But we sort of knew that right away. So it was, for me, bundled up in the grief immediately after the vote and the FBI not coming to interview me and my corroborators. And the logistics involved—where the executive branch is overseeing the FBI, so they're the ones deciding whether they want to look at those tips or not. The process was the most disappointing part about it. The outcome was less disappointing than the process. You write that you've moved into the phase of “radical acceptance,” but how would you like to see the process work for people who might come forward with information that should be heard in the future? I'm concerned that people won't come forward, given the process that they've witnessed. I think in the workplace and in other settings where you have H.R. and Title IX and other protections, it's maybe a little bit safer—a little bit more defined, at least. And in [most] workplaces, you're not allowed to retaliate. And so I think that, at minimum, we need to make sure that there's no retaliation against people for speaking up in a government setting. I think we're better than that. One of the most moving scenes in the book is during the summer of 2018 when you’re deciding how to come forward with what you know about [then-nominee Kavanaugh]. And your older kid is kind of intuiting what's happening but doesn't totally know…. He was noticing my behavior was a lot different at the beach that summer—I was talking to my friends excessively, and we were very serious and focused rather than relaxed. We were on a very tight timeline: The president had said that there was going to be a nominee selected in one week, and when Brett was on the shortlist that week, I was certainly just behaving differently. And kids pick up on these things, so he asked about it a few times. I kept it as simple as possible and said, “Someone that I know from high school who did something really bad to me is being considered for a really important job by the president, and I need to let him know.” When I first told him, he said, “Well, that's really nice.” He said it with a tad of confusion. And then, the next day, he came back to me and had thought about it, and he said he probably had an idea of what might have happened to me and that he was really sorry. What a loving response. That’s what you’d want to hear from anyone. He’s a great kid. I'm really lucky. And in my mind, it was like, “Oh, now I can go forward. He's okay with it.” What you went through in 2018 left such a long shadow over the last five years for you. And I'm curious: What are the moments where you feel like you can be liberated from thinking about all of that and just be you? Minimalism is now my new way of being, and I've just found that really helpful—to reduce the complexity of life, for now. That's where I feel like I can be myself: outside or in the ocean or just among a small group of friends. So not in the mosh pit at a Metallica concert? Oh, there, too. There too.  ABOUT CINDI LEIVECindi Leive is the co-founder of The Meteor, the former editor-in-chief of Glamour and Self, and the author or producer of best-selling books including Together We Rise. Her related listening recommendation: Anita Hill and Christine Blasey Ford, in conversation for the first time here.  ENJOY MORE OF THE METEOR Thanks for reading The Saturday Send. Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy and The Meteor’s flagship newsletter, sent on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

"I'm Here As Long As I Can Be"

"I'M HERE AS LONG AS I CAN BE"

Texas abortion provider Ghazaleh Moayedi, D.O., provides care for her neighbors—but she has to leave the state to do it

By Susan Rinkunas

After Ghazaleh Moayedi graduated college, she got a job working on the administrative side of Whole Woman’s Health, an abortion clinic in Austin, Texas. She respected the providers who chose the work—many of whom had witnessed illegal abortions before Roe v. Wade—but also thought the patients deserved doctors who looked like them. “I didn’t have the language for it at the time,” she says “But I noticed these doctors, older white men, didn’t reflect the people that we were taking care of. I knew that we needed new doctors.”

So, she went to med school and became an OB/GYN and complex family planning specialist in Dallas in 2018. Less than two years later, Texas lawmakers enacted abortion bans, first during the height of the pandemic, and then via the 2021 bounty hunter law known as Senate Bill 8. A few months later, Roe fell, and now Moayedi travels to Kansas to provide abortions—often to other Texans. I talked to her about what she’s doing to care for people after they return home, and her message for people living in Democratic-led states who think they’re safe from abortion bans.

Susan Rinkunas: When did you start traveling to provide abortion care?

Ghazaleh Moayedi: I started traveling to Oklahoma in 2020 [after] Gov. Greg Abbott shut down abortion care in our state under the guise of COVID restrictions. Abortion doctors traveling is common—but never from a state like Texas to somewhere else. That is the novel piece over the last few years. It’s always a doctor who lives on one of the coasts traveling to a restrictive state. That was a moment where I was like, ‘Oh, crap. In order to take care of Texans, I’m gonna have to start traveling.’ I started working at a couple of clinics there, in addition to the clinics I was working at in Dallas, and did that until Oklahoma shut down—it was about a month or so before Dobbs. Now, I am traveling to Kansas and working in a clinic there.

You’ve said it’s surreal to be a Texan leaving the state to care for other Texans leaving the state. Are you commiserating with patients? Do they know you’re from Texas?

I usually ask people when I make small talk when I’m doing an ultrasound. Like, “Where are you coming in from?” And people usually say Texas, then I ask where. “Oh, where in Dallas? I’m from Dallas, too, that’s why I’m asking.” I can just see people’s faces change. When I say, “Did you eat at that place? That place is really good,” I can see the light coming from people. It’s a moment for us both. We’re like, “Yeah, this is bullshit. It’s totally bullshit that we’re both here.” I had a patient who was like, “I wish you could have just done my abortion in the closet at this restaurant that we both knew.”

During a fall trip to Kansas, two of my patients were on the same flight I took. I’ve still been really processing that in and of itself, that we’re all on this flight together, how just stupid, pointless, [and] inhumane this is.

Are there certain patients you can’t stop thinking about?

I’ve had patients whose partners have lost their jobs because of the time they have to take to come and travel. There’s a ripple effect of harm that happens from people needing to travel to get abortions.

When someone does a medication abortion [as Dr. Moayedi sometimes does for Texas patients in Kansas], there are rare cases where it doesn’t work. If I’m seeing them in Texas for an ultrasound afterward but there’s still a continuing pregnancy, it’s like, “Shit, you’ve gotta go out of state again.” I can’t do anything for them, and it’s unconscionable. Before [Dobbs], someone would show up a week after their medication abortion, and I could be like, “Yep, everything looks good” or, “Nope, it didn’t work. Okay, I can do an aspiration right now for you.” Now, it’s a never-ending saga.

In other states [like Kansas], it’s “take your medication abortion, and then in five weeks, take a pregnancy test.” Some of these people are waiting five weeks to be able to fully confirm that their abortion is complete. Not only did they have probably several weeks of waiting to get an appointment, get out of state, then do their pills, then come back—but now they’re going to have to wait another month to know that it’s complete. This is like a two-month minimum cycle in someone’s life of just trying to end this pregnancy.

I’m definitely seeing people making that calculation [about medication abortion] in their mind of, “Wait, then I have to wait to know that it’s done?” They’re so stressed out—they had to do all this travel—that they’re like, “I’m just gonna do a procedure [instead] so I can leave here knowing.” You take good care of them, but states are taking people’s autonomy away, and they’re being forced to make decisions out of this insulting process.

And you’re providing ultrasounds in Texas now?

After a Dallas abortion clinic closed in spring 2023, I started a little ultrasound practice so that, at least for folks in my general area, people don’t have to wait five weeks [to find out if their pills worked]. They can get an ultrasound with a trusted provider who isn’t going to judge them and who has deep experience in abortion care.

People really need a community-based provider that they can turn to when they come back [from an out-of-state abortion], someone that they can trust and talk to. It sucks not being able to provide abortions [in Texas]. But it is this whole new chapter of my work. It feels really good to still be able to take care of people in the ways that I legally can.

I mean, folks are going to crisis pregnancy centers for ultrasounds before and after abortions because they’re free. People are able to schedule appointments with me via Pegasus Health Justice Center. I have a cash rate that’s $250, but I’m working with abortion funds, and pretty much everyone is able to get funded.

Have you thought about leaving Texas?

There isn’t such a thing as a safe state. We are one country, and these types of tactics are coming to every state. This mentality isn’t concentrated here [in Texas]. It exists in states without abortion restrictions as well. But people have this false belief that they are safe in these bubbles, and even within states like California and New York, the [anti-abortion] mentality exists. This extreme right, fascist, white-power movement exists everywhere, and abortion restrictions are an extension of that—they’re not separate from it.

After the Dobbs decision, I was feeling really low, even though we knew it was coming. It was like, “What the hell am I gonna do?” I considered moving and told my friends. I started looking at Zillow everywhere, like, “What’s New Jersey like? What’s Michigan like?” I interviewed for a few jobs in other states, and that was a couple of months of pouting and wondering what I was going to do. But I’m not going to escape from white supremacy anywhere in this country. I can move somewhere else and have a little bit more leeway in my work, but until when? We might have a president that is literally presidenting from jail.

Right, there could be a national abortion ban in January 2025.

Exactly. The reality is, I could pick up and move my whole family, and we could go somewhere “safe” for a period of time—and then what? I’m here as long as I can be. I think the idea that this is concentrated [in Texas] is really short-sighted. Everyone has a role to play in combating white supremacy and fascism within their own communities.

There’s a ripple effect of harm that happens from people needing to travel to get abortions.

What do you think of the talk online where people urge doctors to defy hospital orders and perform abortions in health emergencies?

It makes me incredibly annoyed and pissed off. That’s not how hospitals work. It’s not like I can just waltz into an operating room and say, “I am ready to do a surgery now.” Even when any hospital I worked at allowed it, there were still often multiple hoops I would have to jump through. Sometimes, even though it met all of the policy guidelines, there was someone who delayed the case because they needed to talk to someone who needed to talk to someone.

Doctors don’t own the hospital. We don’t actually direct anything in the hospital or schedule cases. There are multiple layers of people that have to approve things and even once it is approved, financially and policy-wise, you can still show up on that day and your anesthesiologist refuses, the nurse refuses, the tech refuses. I can’t do it alone in a hospital. I

could go to jail. I could lose my medical license, and then who am I going to help?

And rather than suggesting medical providers flout state laws, there are people organizing community networks for abortion pills, like Red State Access.

What pill networks are doing—that’s envisioning the future and being the future that we want and doing the work that needs to be done at the community level. That is how we change culture. That is how we address people’s needs in the moment, and we live out the future that we want. We’re saying we don’t need the courts to let us live the free lives that we can have. We actually have autonomy over ourselves.

That is, on all these micro levels and within communities, what people need to be doing: envisioning and living within the just future that we all deserve.

The Abortion Pill on Trial

FEATURED STORY

One of its key researchers says Mifepristone was tested “with three times or more rigor” than other drugs.

BY SAMHITA MUKHOPADHYAY

Today, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the first abortion case to come before the court since it overturned Roe v. Wade. The case, brought by the extremist group Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine (AHM), is challenging the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—specifically the FDA’s 2016-2021 policies, which expanded access to the safe and effective abortion drug mifepristone, initially approved in 2000 and now the most common abortion method across the country. AHM’s main argument? That the FDA did not adequately study mifepristone’s safety risks. (We explain it more in-depth here.)

The implications of this decision could be disastrous. As Fatima Goss Graves, President and CEO at the National Women’s Law Center, told us, “Banning mifepristone would upend abortion care not just in the conservative states that have been racing to ban it—but in all 50 states, no matter their laws.”

But the case itself is farfetched, argues Dr. Lisa Haddad, the medical director for the Population Council’s Center for Biomedical Research, the nonprofit research center that led clinical testing on mifepristone more than two decades ago. In fact, she points out, over 5 million people have successfully used it since then.

With the case now before the court, we spoke to Dr. Haddad and Dr. Beverly Winikoff, who worked at the Population Council for 25 years, where she was Program Director for Reproductive Health and Senior Medical Associate at the Council, which was the team that led clinical trials on mifepristone overseas. Now she serves as president of Gynuity Health Projects.

Samhita Mukhopadhyay: You worked with the organization that facilitated the FDA approval of mifepristone—what are you feeling right now?

Dr. Beverly Winikoff: I feel like I’m charging into the skirmish. I’m getting girded up. Can’t these people ever go away? But it is very, very encouraging to see how everyday people understand that this is a highly political, not a scientific discussion.

Dr. Lisa Haddad: I feel very frustrated and a little bit beaten up. And while I’m inspired by some of the voices speaking up in support of mifepristone, I see this trend in reducing access for women, and I’m scared that the science and the excellent evidence that supports this as a way to improve health outcomes will be overlooked and minimized. It’s a slippery slope.

BW: I think in the end, it’ll be okay because of the politics—the FDA is there to do a job, and it has always done it quite well in protecting the public. And this is an attack on the FDA. When you look at it that way, there are many people who are on our side, including big pharma—because if this happens, they have no [incentive] to be able to put money into new drugs because somebody could come up and decide that they don’t like that drug and they can [sue to] override the FDA, and that would be chaotic in the pharmaceutical world. It’s not just abortion; it’s every drug that gets approved. I think the politics of it is much bigger than abortion.

That’s a good point. Can you walk us through what we need to know about the FDA approval of mifepristone? Was it the standard approval process or was it a long, hard-fought win?

BW: It was cover-your-ass time the whole way along by the FDA. That was it. That was the theme. So, every single thing was done with three times or more rigor than any other drug I’ve ever heard of. But that’s okay because the drug is very good and very safe. We also got the FDA staff to be very excited about it. People were really very interested in making sure it got through.

When we did the final studies, we had several thousand people, and it performed very, very well. We were very attached to this product because it seemed safer and more effective than you could expect. So people were very excited about it because it had the potential to be a workaround for some of the political stuff of having to go to a clinic. You were doing it at home.

Dr. Haddad, can you speak to the significance of Tuesday’s case? Depending on the decision, what could the implication be?

LH: An increasing number of individuals are getting access to abortion only through medication abortion. I’m in Georgia, where we have a 6-week abortion ban. Finding out that you’re pregnant, making an appointment, getting off of work, getting a way to get there, and all of that before six weeks is hard. But if people make it to the clinic, medication abortion at that very, very early gestational age is a potentially good option for individuals, and the addition of mifepristone [generally used with misoprostol] enhances the likelihood of success. Also, without mifepristone, the barriers to access are huge. It’ll make it even harder for more individuals to obtain care.

And what could this case mean for misoprostol?

BW: Well, one of the things that mifepristone does is soften the cervix. So that means that whatever’s coming out doesn’t have as hard a time. And there are a lot of pain fibers in the cervix, so it could be more painful to just use misoprostol. But you can do it for most people. It will work, but it’s not maybe as pleasant.

LH: An abortion with mifepristone is gentler on the body, it gives the person a little bit more control, and it’s more predictable in terms of how it’s going to go.

BW: What saves the day for some of these other drugs is that they have other uses. So methotrexate is also abortifacient, but nobody’s trying to take that off the market. Nor misoprostol, actually. [Methotrexate is used for cancer while misoprostol can be used to treat ulcers and to induce labor] And so I think one of the things is maybe to get drugs that have dual purposes.

LH: And there are opportunities for that. Mifepristone does have utility for other indications. There’s excellent evidence that it’s great for fibroids and that it can be used for contraception. There is evidence, and it’s used commonly as emergency contraception in many countries. It’s just not approved in the U.S., and so I wonder whether or not that would enhance its security.

BW: Yeah, somebody should put it in for approval.

LH: We’re actually trying to garner support to do that right now, Beverly. But again, the evidence in the [case] is ridiculous when you break it down. It’s challenging the ability of scientists to make a decision, but not on all issues, just an issue that bothers [the plaintiffs] morally. But it’s not based on science. It’s frustrating to see because just the fact that we’ve gotten this far—I mean, it shouldn’t have a foot to stand on, and yet it is at the Supreme Court.

BW: I think it’s a terrible thing for individuals—not just people wanting abortion, people who want to use drugs for anything.

LH: And even, I mean right now, the standard of care shows that the mifepristone regimen works better for miscarriage management. This focus on something that really shouldn’t even be questioned just highlights the [message] that women are not trusted, women need to suffer, and that doctors and scientists can’t be trusted. Also, on top of what Beverly said, I just want to highlight that it’s not just the FDA that says [mifepristone] is safe. All of the different medical agencies like ACOG and the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, say that mifepristone is incredibly safe with very few adverse events. We know the risks are incredibly low, less than 0.3% of any sort of serious, major adverse events. The risk of death is almost non-existent, whereas if you compare that to forcing somebody to continue with a pregnancy, we know that those risks are.

Over 5 million people have used mifepristone for either medication abortion or miscarriage management. This is not something that is not well evaluated.

As of right now, medication abortion is still available. Learn more here.

Reproductive justice for all of us

REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE FOR ALL OF US

Rebecca Cokley on how to stop the violence disabled people experience

By Shannon Melero

“It is better for all the world if…society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind.”

That sentence, written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1927, was the defining sentiment behind the seminal Supreme Court decision Buck v. Bell—a case that allowed states to continue the practice of forcibly sterilizing those it deemed unfit to reproduce, namely people of color, the physically disabled, and those considered to have mental “deficiencies.” In the specific situation behind Buck v. Bell, the plaintiff was Carrie Buck, a young white woman in Virginia who was forcibly sterilized for her “feeble-mindedness” under that state’s Eugenical Sterilization Act.

It would be easy to dismiss that ruling and Holmes’ words as a relic from another time if the practice of forced sterilization hadn’t lingered so long after that case. Over the course of the twentieth century, roughly 70,000 Americans (mostly women of color) were forcibly sterilized—a practice activist Fannie Lou Hamer famously labeled the “Mississippi appendectomy.” And while the work of activists like Dr. Helen Rodriguez-Trias, founder of the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse, brought some change in the 1970s, forced sterilization is still a painful reality: As of 2022, there are 31 states where the practice can be authorized by a judge and/or performed on a disabled person without their consent.

Rebecca Cokley—the preeminent activist and program officer of disability rights at the Ford Foundation—encountered this situation firsthand while giving birth to her daughter in 2013, and she shared the story onstage at Free Future 2023. As she was undergoing a C-section, Cokley recalled, her anesthesiologist said to her OBGYN, “While you’re down there, why don’t you go ahead and tie her tubes? Because kids like her don’t need to have kids.” Cokley’s OBGYN refused and, as Cokley put it, almost “jumped over the drape to beat him to a pulp.”

But for many disabled people in America, that kind of support is non-existent. Instead, they’re left at the mercy of a medical system that, by design, excludes them. A 2023 study published in The Lancet found that “32% of health care professionals hold explicit preferences for non-disabled people over disabled people.” And as Cokley explains, the practice of forced sterilization is part of a larger pattern of disabled people—”especially women and girls”—being denied bodily autonomy: “You’re never told your body is yours and you have the right to say no,” she points out. “You’re never given ownership over your body.”

Other advances have helped safeguard the rights of disabled people in certain areas—from the educational reforms of Thomas H. Gallaudet in 1817 to the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990. Cokley and others want to ensure that reproductive justice, and the rights of all people with disabilities to have children how and when they want, is on the table, too. “We have an unequivocal right to bodily autonomy, and to make these choices,” she says.

Cokley also notes, “Every policy recommendation moving forward on reproductive health, rights, justice, must include a disability lens. So when hearing about people having to travel across multiple states to access [abortion] care, I want the public to think. ‘So what would that mean if you’re disabled and say, don’t have access to accessible transportation, or need other assistance?’”

You can watch Cokley onstage at Free Future 2023, in conversation with Catalina Devandas, the UN’s first Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and human rights advocate Maryangel Garcia-Ramos, here. (Their session begins at 2:25:25.)

"This Isn't Speedy or Fair"

FEATURED STORY

Lauren Smith’s Waited Over Four Years for Her Day in Court

By Neda Toloui-Semnani

Four months ago, I wrote in this space about Lauren Smith, a 32-year-old mother who lost custody of her youngest child in 2019 after she and her infant tested positive for THC, a cannabinoid substance, at delivery. Smith was arrested six months later and charged with felony child neglect for using marijuana while pregnant—a charge which, in Greenville, South Carolina, carries a sentence of up to 10 years in prison.

When we published the article, Smith’s trial date was set for the week of February 19, 2024, which was, rather poetically, five years nearly to the day after she had delivered and lost custody of her youngest daughter. The child has been living with her paternal grandmother since she was three days old.

But weeks before the trial was set to start, Smith learned her court date would be pushed for a third time. It is now scheduled for the week of April 22.

“Isn’t everybody due a speedy, fair trial?” Smith told me earlier this month. “This isn’t speedy or fair.”

The latest holdup comes after the Greenville County solicitor’s office entered more than 125 pages of new documentation into discovery. This is called a “document dump,” a legal maneuver in which one side enters hundreds, sometimes thousands, of pages of new documentation within weeks of trial in an effort to overwhelm the opposing side. (This is the second time the prosecution has used this delay tactic. The first was last May when they entered several hundred additional pages of documentation as discovery.)

Despite the U.S. Constitution guaranteeing the right to a fast trial, Stuart Sarratt, a former Greenville County public defender familiar with the Smith case, says, “South Carolina essentially does not have any kind of right to speedy trial.”

“We do on paper, but our Supreme Court has interpreted it as basically unless it’s been four-plus years, they’re not going to do anything about it,” he explains. “And really, you have to be in jail for them to really care about it.”

Smith has been awaiting trial for more than four and a half years. The Meteor’s requests for comment from the Greenville County solicitor’s office have gone unanswered.

However, most South Carolinians—including the state’s Attorney General, Alan Wilson, a Republican—agree that the state’s judicial system is buckling under the weight of an extraordinary judicial backlog. Wilson is asking state lawmakers to expand his budget by $1.6 million dollars to help tackle the pile of serious criminal cases, including murders, that have been languishing for years. Against the backdrop of that backlog, state prosecutors, called solicitors, have a great deal of power over which cases make the trial docket. In Smith’s case, the prosecution proposed the trial date months in advance—but then introduced new documents within weeks of that date.

It is unclear what the prosecution hopes to prove with the entry of these documents, but they include medical records for Smith’s child. The Meteor has reviewed these records, which document her doctors’ visits from birth to the present; the most recent show that she was referred to and evaluated by an occupational therapist, who conducted a test to measure the child’s fine gross and fine motor skills—skills like grip on a spoon, object manipulation, physical reflexes, and other developmental milestones.

Advocates for parents like Smith have concerns about bringing records so long after pregnancy into a case. “The idea that your pregnancy-related conduct could be litigated when the kid is five or six, because, by some measure, they might not be hitting their milestones, feels so deeply problematic to me and not vested in any sort of understanding of causation versus correlation,” said Dana Sussman, the deputy executive director of Pregnancy Justice, a nonprofit who advocates for pregnant people caught in the criminal justice system.

The Meteor spoke to three occupational therapists, all of whom agreed that evaluations like the one listed above cannot diagnose why a child’s motor skills have progressed or been delayed.

“Children don’t meet milestones for all sorts of reasons and for no reasons at all,” Sussman notes. “I don’t think we know of a case right now that we’re working on that involves allegations that developmental milestones are not being hit, and therefore the mother deserves to be criminalized.”

As reported in the original piece, all American medical associations recommend abstaining from using cannabis and/or cannabinoid products during pregnancy and while breastfeeding, but the precise impact of marijuana use during pregnancy on the fetus and the child is both uncertain and under-researched. As outlined in the original story, Smith’s case is closely tied to the legal theory of fetal personhood and the ways the government is increasingly policing pregnant bodies (see the Alabama Supreme Court’s ruling on I.V.F. and so-called extrauterine children).

While Smith has been waiting for her day in court, she says, she’s been working at a nursing home and living with her mother and two older children. She tells The Meteor she hasn’t been allowed to see her youngest daughter since early November.

“This is half of a decade now of this back and forth, almost five years, and it’s just been continued and continued and continued,” Smith says.

Still, when asked where she sees herself in five years, she says her work with senior citizens, people who are at the end of their lives and have a long view of life, has given her both perspective and confidence. She plans to be a registered nurse.

Gretchen Sisson on Inequality in the Adoption System

ARE WE ALL WRONG ABOUT ADOPTION?

“It is so often framed as a “reproductive choice,” but I think it’s better understood as an expression of resourcelessness and constraint.”

America loves an adoption story. It’s got all the feel-good elements we love to romanticize: A baby is born to parents unable to care for it, a hopeful family is given the gift of an unwanted child, and everyone lives happily ever after. But the truth, many experts say, is that the institution of private adoption in America is mired in dysfunction, exploitative practices, and systemic inequities—and in far too many cases, almost no one lives happily ever after.

This dysfunction is what interests Dr. Gretchen Sisson, a qualitative sociologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and author of a new book called Relinquished: The Politics of Adoption and the Privilege of American Motherhood. Through over a hundred interviews with American mothers who placed their children for adoption between 2000 and 2020, Sisson’s book aims to debunk myths around an institution I’ve thought a lot about myself: As a transracial adoptee whose memoir, Surviving the White Gaze, is cited in Sisson’s book, I was eager to sit down to talk with her about the politics of adoption. And so, an adult Black woman transracial adoptee meets a white woman sociologist on Zoom. Here’s what happened.

Rebecca Carroll: You chose to interrogate the institution of adoption through the experiences of birthmothers—why?

Gretchen Sisson: The question that brought me to the work in the first place was understanding how women end up choosing adoption. “Choosing” is a loaded term, but how they end up on the path to relinquishing their children, and what the circumstances are around that.

And what were your main findings?

I think the two most important takeaways are, first, that adoption does not offer any meaningful alternative to abortion access. Not only are people who need abortions generally uninterested in adoption, but people who relinquished for adoption usually wanted to parent their children. Adoption is so often framed as a “reproductive choice,” but I think it’s better understood as an expression of resourcelessness and constraint. Rather than an “empowered option,” it is often a reflection of a lack of power. And, second: that adoption generally does not serve relinquishing mothers well. The grief, trauma, and disconnection of adoption belie the idea that it is unambiguously “beautiful”—and nearly all mothers came to a place of critique and cynicism that acknowledged this, with many carrying complex feelings around regret and loss.

You write in the book about how, in popular culture, birthmothers are generally portrayed as either happily moving on or becoming pathologically dangerous. Were there depictions that birthmothers you spoke with felt accurately reflected their experience?

Many of the mothers were drawn to The Handmaid’s Tale. The entire history of Handmaid’s Tale is very complicated, and I don’t want to gloss over that, but that [book] resonated most for them. That one, this extractive child-taking was acknowledged as a loss within the context of the show. And two, that the forces that were separating [birthmothers from their children] were driven by these regressive, religious, racialized, patriarchal ideas.

There is a real dearth of stories told from the perspective of adoptees, and so I’m curious to know how and when you chose to include insights from adoptees in a text centered on birthmothers.

The place where I draw the most heavily on the words and work of adopted people is where I’m talking about transracial adoption. And that’s because the white birthmothers of biracial children that I interviewed had so little sense of what their children were going to need as people of color. I needed to account for the fact that I was only telling part of this story. Sometimes, we’d get halfway through the interview, and I’d ask, “Is your child white? Is your child biracial?” And they would say, “Oh, yeah. He is half Latino, but he looks white, so it doesn’t matter.”

The birthmothers you interviewed for the book are primarily white. Was that a specific choice?

My 2010 sample was almost entirely white women because when you look back at the last set of good data from the ’90s, the people who [were] participating in private adoption systems were white women. There were virtually no Black or Latino women participating in the private adoption system at that time—which doesn’t mean that they were protected from family separation. Their families were just being separated within foster care and family policing systems. But [as of 2020], we’re seeing far more participation from women of color, and particularly Black women, in the private system than 20 years ago.

Did you discover any glaring differences in feelings around the choice to relinquish between Black women or women of color and white women?

Mothers of color who were relinquishing, particularly Black mothers, thought about race very deeply. They would say they weren’t going to relinquish their child unless they could find Black adoptive parents [and] if they couldn’t find Black adoptive parents, they would need to make other concessions. So it might be, “Well, at least these white adoptive parents have already adopted a Black child, so he is not going to be the only Black child in the household.”

One story I share in the book is about a woman who was a transracial adoptee herself from Central America, so she’s a Latina. She was raised by white parents. She had a daughter whose birth father was Latino and she ended up placing her daughter with a Southeast Asian, Indian-American family because those were the only non-white parents that the agency offered her. And so, she thought, “This is still a transracial, trans-ethnic adoption, but at least she’s not with white people.”

When it comes to Black children in white homes, it’s white folks choosing the standard of everything—beauty, education, food, acceptable behavior. Were you able to have that conversation with any of the white birthmothers who had relinquished children of color?

When I did follow-up interviews, they were much more aware of it because they’re mostly in open adoptions, and their relationship with their child made them have to be more aware of it. Were they particularly attuned to the extent to which the entire system of adoption is predicated on a racialized idea of family? No. A few of them did, but that was not the norm. There was one mother whose child was Black/white biracial, and she wanted a biracial couple to adopt and couldn’t find one. So she chose a gay couple that lived in New York City. That was her concession, but she was like, “I still feel like I failed him. I wish I could go back and talk to my younger self and be like, ‘No. Don’t give up. Don’t accept this from the agency. Go to a different agency. Fight harder for this.’”

And how do you think celebrities have played a role in marketing transracial adoption?

I think that’s huge. You see Madonna and Angelina Jolie with their well-publicized transracial adoptions in the early 2000s. I think those narratives are important: Yes, we can love people who don’t look like us. [But] it entrenches this idea of transracial adoption as a symbol of progress that wasn’t attuned to what adopted people needed. And it sold the idea of adoption as white saviorism—that the way we’re going to take care of African children is by extracting them from their countries and bringing them here, rather than focusing [freeing these countries] from the conflicts and economic and geopolitical instabilities that drive the exporting of children.

How do you think we got from white folks saying, “Let’s go to Africa and steal Black folks and make them slaves,” to white folks saying, “Let’s go to Africa and buy Black folks and make them our children”?

I talk about enslaved mothers as relinquishing mothers, and I think their closest corollary and counterpart in modern society are mothers who lose children within the systems of family separation. Because I view child welfare and family policing as a system that is about punishment in a way, similar to what Black women have always faced in the United States. The common thread for me is that we don’t recognize any value in preserving Black families.

As an adoptee, reading your book was a lot. And I wonder, even in the best-case scenario, is it an institution that we should uphold?

I do talk about people who take a reform approach to adoption, who want to explore the idea of ethical adoption. There are policy proposals out there to change the marketing of adoption. I think that there is value there. I’m glad that there are people working in that space.

What is ethical adoption? Is that a thing?

As I mention in the book, there are aggressive marketing tactics being used towards vulnerable pregnant people to sell adoption to them. There are unscrupulous players trying to insert themselves into a system purely for making a profit, and regulating that is ethical. But are we reforming the system to make it actually serve people? Or are we reforming the system so that we feel better about it, but it’s still deeply harmful? What’s more exciting to me is thinking about what family preservation looks like. And that’s not just about policies that support families and provide a meaningful social safety net, but it’s about [questioning] the idea that the only way to support and care for children is within these legalized parenting relationships. What advocates are arguing for is a more expansive idea of how we provide care for families and children outside of the legal transfer of parental rights.

A World Without Exceptions

FEATURED STORY

The devastating consequences of the Dominican Republic’s absolute abortion ban

Standing on the threshold of her home, Niurki, 18, holds her fussy two-year-old baby boy in her arms and surveys the only landscape she’s ever known. The rusty tin roof on her weathered, pale yellow house barely offers protection against the elements. Niurki lives in San Cristobal in the Dominican Republic, a country that attracted seven million tourists in 2022 alone. But it also boasts one of the highest rates of teen pregnancies in Latin America, a consequence of several factors, including the total abortion ban in effect there since 1884.

Niurki didn’t want a baby. Her ex-boyfriend and the baby’s father, Carlos, left her the day that she found out she was pregnant. Niurki says she didn’t consider an abortion because of her Catholic faith. But it wouldn’t have mattered; the procedure was illegal anyway. So she had the baby, and, like 44% of teen moms in the country, eventually had to drop out of school to raise her now toddler. Today, Niurki is unable to work because she does not have access to childcare. Her ex is forced to pay child support, but it’s a paltry $35 per month. “I depend entirely on him,” she laments. “Most of the time, he’s late, and we’re left with nothing.”

“The worst,” she tells me, her voice still childlike, “is when I don’t have money for food or milk. I make some fruit juices to calm the baby’s hunger, but he keeps crying. It’s despairing.”

Niurki had never been taught about family planning, condoms, or birth control before she had her baby. Now a mother, she’s stuck at home, unable to make a living or pursue her studies. Today, Niurki supports activists who have been campaigning for decades for what they call “las tres causales,” or the three exceptions—measures that would lift the ban in cases of rape or incest, when the life of the mother is at risk, or when the fetus is not viable. President Luis Abinader had promised to support the three exceptions during his campaign, but he has failed to make good on those promises since he took office in August 2020. In July 2021, the Senate of the Dominican Republic voted 23-3 to support a criminal reform bill stripping out any language about the three exceptions.

The United States is months away from a 2024 election, in which the two leading Republican candidates for president and many of those running for Congress have vowed to pass a national abortion ban if they win. The dire situation for women in the Dominican Republic gives us a window into what that might mean for pregnant people here—including teenagers who are denied authority over their own bodies and their families.

No choices; devastating consequences

In the Dominican Republic, the responsibility for every aspect of reproduction—from preventing it to raising children—falls entirely on women. “Less than one percent of men use condoms,” Dr. Lilliam Fondeur, a gynecologist and activist, tells me during a conference on reproductive rights in Santo Domingo, the country’s capital. Sexual education in schools is practically nonexistent because, doctors say, even talking about sex is perceived as encouragement. And while contraceptives are theoretically available, 46 percent of women either don’t know about them, can’t afford them, or are reluctant to ask because they fear people in their communities will find out. However, sterilization is a common method of contraception in the Dominican Republic, particularly among women who are married or in domestic partnerships (30.5 percent), but 25 percent of women who opt for sterilization don’t understand the procedure is irreversible. “On the one hand, the government tells you not to abort,” Dr. Fondeur says. “On the other, it doesn’t provide the means to avoid pregnancies.”

And the punishment for trying to end an unwanted pregnancy is severe: In this fervently Catholic and conservative country, which bears a Bible on its flag, women risk six months to two years of jail time. Meanwhile, for health professionals like Dr. Fondeur, the punishment for helping someone terminate a pregnancy is between five and 20 years of imprisonment. “Professional secrecy isn’t worth a damn,” Dr. Fondeur says. “You can go to jail even for only providing information. You don’t want the woman to die, but you have no alternatives.” As a result, she says, “twenty percent of teenage girls, mostly from rural and lower-income populations, are mothers. [In too many cases], they have babies with men up to 50 years older who tend to abandon them by the time they’re 18.”

But bans on abortion do not reduce the need for them. The Dominican National Health Institute estimates at least 100,000 illegal procedures occur per year. At least eight percent of all maternal deaths are estimated to be the result of those who tried to terminate their pregnancies but died from infections and bleeding, and around 25,000 more women are hospitalized every year as a likely result of unsafe abortion.

“Professional secrecy isn’t worth a damn. You can go to jail even for only providing information. You don’t want the woman to die, but you have no alternatives.”

And as in the U.S., the consequences of criminalization are also dire for those with wanted pregnancies. Damaris, a 31-year-old Dominican woman of Haitian descent, experienced terrible pain in her abdomen 16 weeks into her third pregnancy. Her sister Juliana told me she took Damaris to more than five different hospitals and clinics—all of which claimed they didn’t have the means to perform a sonogram, something Juliana later learned was not true. In an apparent effort to avoid abortion, “they went as far as to pretend the baby was still alive when she was, in fact, dead,” she says. With the dead fetus inside her for several days, Damaris went septic and ultimately died in great pain. “She left a son who, because of her death, has refused to go to school ever since, a daughter who tried to cut her veins and survived but still has no friends,” Juliana says, “and a father who succeeded in committing suicide after various attempts.”

Those stories are everywhere in the Dominican Republic. When Rosa Hernandez’s daughter, Rosaura, began suffering from high fevers and getting bruises all over her body at 16, Rosa brought her to Santo Domingo hospital. There, on July 2, 2012, she was told that her daughter was four weeks pregnant. What she wasn’t told was that Rosaura had a deadly and fast-moving form of leukemia and needed urgent chemotherapy that was denied to her because of her pregnancy. She was suffering but wasn’t prescribed painkillers—also allegedly to protect the fetus. “Get me out of here! They’re going to kill me!” Rosaura told her mother. Rosa begged the doctors. “I humiliated myself. I went on my knees,” she remembers. Rosaura was only given chemotherapy on July 26—three weeks after her diagnosis—and died less than a month later on Aug. 17.

There is only one organization in the country—the Colegio Médico Dominicano—that, alongside other mandates, protects women inside hospitals where this kind of obstetric violence is rampant. Francisca Peguero, an advocate for the Colegio Médico Dominicano, told The Meteor that if women arrive bleeding because they tried to provoke an abortion or have an infection, hospitals treat them without painkillers. “They are guilted and singled out in the eyes of the community,” Peguero says. “When a woman dies giving birth, there are no investigations; it’s simply filed as internal bleeding.” She tells me about one of the most painful cases she’s seen in her 30-year career: a 14-year-old girl with a banana stuck in her uterus, the only method she had thought of to abort. The girl had been reported to the authorities by her own mother, and when she was taken to the hospital bleeding, policemen were waiting for her in the next room. Later, Peguero found out the girl had died from her injuries and that her pregnancy was the result of incest.