Break Up With the Manosphere

We’ve seen what the bros have built. We can do much better.

BY SHANNON WATTS

It feels like months since Donald Trump took office, but it was just 12 days ago. In that short time, we’ve experienced the whiplash of executive orders, confirmations, and quiet erasures of government workers. Dangerous cabinet members have been confirmed. Diversity and equity gains were gutted with the stroke of a pen. The federal government’s reproductive rights webpage disappeared overnight as if it had never existed (but here’s the archived version). The chaos is all-consuming—each move expected, yet somehow still landing like a fresh gut punch.

Trump is operating from the playbook he promised voters, but watching men whose own family members have accused them of predatory behavior march into positions of power while women are marginalized feels like a full-throated “fuck you” to feminism. It’s as if the men who are now in power are hellbent on rolling back all of the progress women have made since the 70s and they’re reveling in their revenge.

To be clear, Trump’s victory wasn’t just an election loss for the majority of American women who voted against him; it was a cultural rejection of female power facilitated in large part by the manosphere—a toxic, hyper-masculine echo chamber of podcasters, influencers, and bloggers who have spent years weaponizing misogyny. Their movement laid the groundwork for this moment, and right now, it feels like they’ve won.

A little history

The manosphere gained early visibility during flashpoints like GamerGate in 2014, where online harassment campaigns targeted women in gaming and tech, and the horrifying 2014 Isla Vista shootings by Elliot Rodger, who left behind a manifesto filled with misogynistic grievances. These events reflected a growing backlash to the rise of feminist blogs like Jezebel, the increasing mainstreaming of feminism, and women’s voices being amplified in previously male-dominated spaces. This toxic ecosystem grew to include communities like incels (involuntary celibates), Men Going Their Own Way (MGTOW), and Men’s Rights Activists (MRAs), which have long framed feminism as a threat to their identity and power.

But as I sit with the weight of it all, one thing has become clear: if we are going to successfully combat this backlash, we have to build something stronger than outrage alone. Online activism has played a critical role in mobilization and awareness for progressive causes—just as it has for the manosphere—but it’s not enough on its own to win. We need spaces for women in every arena: online, in real life, in activism, in community, and in joy.

We need a womansphere. Because the antidote to the manosphere isn’t just resistance—it’s connection.

The manosphere certainly creates connections but around the worst things. Modern-day manosphere leaders like “alpha” strongman Elliott Hulse, who preaches male dominance and rails against feminism, and far-right provocateur Nick Fuentes, the “your body, my choice” jackass who never met a nazi salute he didn’t like, exploit this resentment toward women, promoting hyper-masculinity as a cure-all for a world they claim is dominated by “woke” ideologies. Their messaging finds fertile ground in online forums like 4chan and Reddit, where misogyny and grievance politics are celebrated. Figures like Andrew Tate openly normalize violence against women, while he currently awaits trial on human trafficking and rape charges.

The manosphere now actively recruits vulnerable young men through everything from bodybuilding forums to gaming livestreams, and thrives on creating enemies: women, feminism, and anyone challenging the status quo. Fear, blame, and division remain the cheap fuel that powers this system, pulling in disillusioned men and weaponizing their grievances against progress.

After the election, it felt as if the manosphere was unstoppable. But then I received an invitation to attend a meeting in San Jose with a group called the Gigis, a community created for “midlife women to gather, grow, and give back.” This regular gathering of nearly 60 women wanted me to lead them in a discussion about what they could do in the aftermath of the election. During our two-hour meeting, some of the women said they were exploring a run for office. Others were starting nonprofit organizations to serve their neighbors. And others were going back to school to hone their activism skills. But all of the Gigis were committed to coming together to encourage each other to keep going.

Like the manosphere, this is a community, and the point of communities—of all types—is to help us find our purpose, test and hone our values, and be a part of something greater than ourselves. I’ve seen firsthand through Moms Demand Action that communities are where the real change happens—in ourselves and in the world. Not only is Moms Demand Action one of the largest grassroots organizations in the nation, but it’s also the largest real-life laboratory for helping women find their people and, in turn, their power. And that’s where we need to focus our energy: on creating in-person spaces that inspire connection and collective action. Unlike the manosphere, which thrives online by feeding on anger and fear, what I’m advocating for is grounded in real, face-to-face relationships, that foster compassion and collaboration. That’s the crucial difference between their network and what I’m calling the womansphere—we don’t just build ideas, we build bonds.

The manosphere understands that people crave belonging, even if their version rallies around a fear of inadequacy. But a healthy community—even if it’s just a handful of people—can help us feel connected to others and feel like we're part of something larger than ourselves. The manosphere thrives on reinforcing outdated power structures. The womansphere reimagines them entirely, creating a space for equity, inclusivity, and growth. Online and offline, where women can connect without fear.

Sitting with the Gigis—knowing that women everywhere, of all different walks, are meeting in their own groups—I realized that the most effective resistance to the Trump administration won’t be en masse, but underground—and it will start in small communities. We need a womansphere where we can come together in person from all walks of life to feel empowered, supported, and seen. We need in-person communities where women can have conversations, despite their levels of education or political views. We need more media and platforms to lift up women’s stories, leadership, and solutions. We need to celebrate and center diverse leadership and lived experiences. And we need to create a womansphere that is as loud and visible as the manosphere, but infinitely more constructive.

To be clear, I’m not talking about the existing “tradwife” communities, where women advocate for a return to regressive, hyper-traditional gender roles and use “feminine wiles” as power. Our womansphere is about real progress, inclusivity, and collaboration—not performative or nostalgic ideas of femininity. The womansphere isn’t just a rejection of toxicity; it’s a blueprint for a better, inclusive future.

The manosphere won’t go down without a weird, gross fight. Right now, they’re gloating, emboldened by political wins and all those inaugural ball invitations. But that’s all the more reason to double down on creating an alternative. In this moment, women, as always, face the harder job. Instead of tearing things down, we’re tasked with building something meaningful, something that endures. We need to work towards something, not against it. And while feminist spaces have historically had their own moments of conflict and division, this new womansphere can learn from the past and make constructive collaboration its guiding principle.

Build your community. Find your people. Start the conversation. This isn’t about perfection; it’s about progress. The womansphere starts now, and it starts with us.

And seriously, our content is way better anyway. Here are a few ways to enter the womansphere:

Podcasts

- America, Who Hurt You?

- Pulling the Thread

- The Amendment

- News Not Noise

- My So-Called Midlife with Reshma Saujani

- Not Gonna Lie with Kylie Kelce

- UNDISTRACTED, with Brittany Packnett Cunningham

Mission Driven Groups

- National Women's Defense League, a nonpartisan organization dedicated to preventing sexual harassment and protecting survivors.

- TOGETHXR, a media and commerce group founded by some of the world’s greatest athletes.

- Women in AI (WAI), a nonprofit do-tank working towards inclusive AI that benefits global society.

- Project Dandelion, a women-led global campaign for climate justice.

- GenderLib, an emergent and innovative grassroots and volunteer-run national collective that builds direct action, media, and policy interventions centering bodily autonomy

- Moms First, grassroots community of moms and supporters taking action in their homes, workplaces, and communities.

Inclusive Journalism:

- The Persistent, a digital journalism platform committed to amplifying women's voices, stories, ideas, and perspectives.

- The 19th News, an independent, nonprofit newsroom reporting on gender, politics and policy.

- them, the award-winning authority on what it means to be LGBTQ+ today — and tomorrow.

- The Gist, a women-led, inclusive, and empowering sports community made for everyone.

- The Meteor, a multimedia company centering the lives of women, girls and nonbinary people. (Hi, that’s us!)

Social Media Darlings:

Emily Amick (@emilyinyourphone)

Your Virtual Anti-Disinformation Bestie (@the.wellness.therapist)

Becca Rea-Tucker (@thesweetfeminist)

Shannon Watts is an author, organizer, and speaker. She founded Moms Demand Action and recently organized one of the largest Zoom gatherings in history, mobilizing women voters for the 2024 Kamala Harris campaign. Her new book Fired Up is coming in 2025.

Two Pop Stars, Both Alike in Dignity

Beyoncé and Taylor Swift face off at the Grammys

BY SCARLETT HARRIS

It’s been an incredible year for women in pop, and this weekend at the 67th Grammy Awards the race for the highly coveted Album of the Year award is stacked with the gals who ruled the summer. Billie Eilish, Sabrina Carpenter, Chappell Roan, and Charlie XCX are among the nominees. And while each of these women has a strong chance of taking home the gold, the real competition is between two titans of the industry—Taylor Swift and Beyoncé, who have 157 nominations and 46 wins between them.

This weekend promises to be a kind of referendum on the notoriously racist and old-fashioned music establishment. All eyes will be on whether Bey, with “Cowboy Carter,” can finally clinch the Album of the Year award that has eluded her her entire career—or whether Grammy darling, Swift, will add to her already record-breaking tally of four AOTY golden gramophones with “The Tortured Poets Department.”

The last time they were pitted against each other in this category was at the 2010 Grammys, for “I Am… Sasha Fierce” and “Fearless,” respectively, which Swift went on to win. This followed Kanye West’s infamous “I’mma let you finish” screed at the MTV Video Music Awards the year prior, in which he interrupted Swift’s acceptance speech for Best Female Video for “You Belong With Me,” asserting that Beyoncé had one of the best videos of all time and should have won for “Single Ladies (Put a Ring On It).” (He wasn’t wrong.) Ever the consummate professional, Bey had invited a deer-in-the-headlights, 19-year-old Swift back on stage during her own acceptance for Video of the Year so she could give the speech truncated by West.

The two have been eerily linked ever since: fans noticed Beyoncé dropped her groundbreaking self-titled visual album at midnight on Swift’s birthday in 2013. The streaming debut of Swift’s The Eras Tour concert film was released on the 10th anniversary of that self-titled album. (Queen Bey showed up to the film’s red carpet premiere, quashing any lingering rumors of beef between the two.) They are the only two women to debut a single at number one on the country charts. And both dominated the cultural conversation in 2024, a year full of women taking back and transforming pop music.

Despite pretty much every other awards body and cultural arbiter giving Bey her dues, and despite a trio of standout albums in BEYONCÉ, Lemonade, and Renaissance, the Grammys routinely withholds AOTY from her (this is her fifth nomination). As writer Kathleen Newman-Bremang explained last year—after Jay-Z accepted the Dr. Dre Global Impact Awards at the Grammys and slammed the Academy in his acceptance speech— Black music is often relegated to the genre categories like R&B, rap, and dance, which Renaissance won in in 2023. Albums by Black women seldom win the general categories like Album of the Year—which was last won by a Black woman in 1999 with The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill.

“[Calling] Black artists the greatest of all time… would require admitting the power of Black art, it would require acknowledging the history of cultural pillaging and musical theft of Black work that the industry was built on,” Newman-Bremang wrote at the time.

Cowboy Carter is a direct response to that kind of racism in the industry, featuring Linda Martell, a Black country pioneer, and her modern-day contemporaries Shaboozey, Tanner Adell, Brittney Spencer, Tiera Kennedy and Reyna Roberts. Despite being her most critically polarizing album in over a decade, Bey will probably win for what is, in my opinion, her weakest body of work since 4. That is if Swift doesn’t best her for the similarly conflictingly reviewed and unwieldy The Tortured Poets Department.

Of course, Grammy voters might surprise us and hand the award over to one of the freshly crowned pop princesses, like Sabrina Carpenter or Chappell Roan. But the fact that Beyoncé will actually be attending the award ceremony this year tells me she expects to be leaving with some hardware. Or perhaps everyone’s just there to have a good time and we’ll still be waiting for an AOTY award in another 15 years (you know, if society holds up in the meantime).

HER LIFE WAS AT RISK. ALABAMA DIDN’T CARE.

FEATURED STORY

Tamara Costa needed an immediate abortion. All she got was a sticky note with the phone number of a clinic 580 miles away. Here’s how one state’s severe laws punish families in terrifying health situations

BY JULIANNE ESCOBEDO SHEPHERD

Tamara Costa was over the moon when, in June 2024, she discovered she was pregnant for the second time. A 24-year-old logistics analyst in Athens, Alabama, she and her now-husband Caleb were already raising a toddler son, Xavier, and were eager to give him a sibling. They began saving for a larger house to accommodate a growing family. Tamara had gotten a pregnancy test at a Publix, sneaking away from her mom to buy it so she could surprise her. “As soon as it was positive, we ran to [Xavier’s] Grandma, like ‘Look!’” she says. “Everyone was all excited.”

But the day after she took the test, Costa began bleeding enough that she went to the hospital, where she says she was told that, four weeks into her pregnancy, she was having a miscarriage. The bleeding had stopped by the time she saw her OB-GYN but, after a routine check-up in mid-July—near the end of her first trimester—genetic testing found that the fetus had a high risk of triploidy, a usually fatal chromosomal abnormality. The OB-GYN then directed her to a maternal-fetal medicine specialist (MFM), trained to diagnose and treat high-risk pregnancies, an hour and a half away in Birmingham.

In early August, the MFM performed a high-resolution ultrasound—and the news was heartbreaking. The fetus didn’t have a skull, the specialist told them; the heart, liver and other organs were outside the body; the lower extremities couldn’t be seen at all. “I was pretty quiet, but my husband was like, ‘Are you sure your results are correct? Are you sure your ultrasound is up to date?’” Costa remembers. “I think we were just trying to hear that there could be a possibility of something different. But the specialist said that Baby would not survive outside of the womb, and there was nothing that we could do. And he said I could get sick, so termination was his only recommendation he was giving—and I had to go to my OB-GYN for more information on that.”

But the OB-GYN did not offer “more information”—at least not in the way they might have hoped. When Costa and her husband arrived at her appointment the following week, they say that the OB-GYN told them that, as they were in Alabama, there weren’t “a lot of resources,” but that she’d see what she could find.

Then she handed her a sticky note with a phone number and the words “Planned Parenthood Chicago” written on it. “She told me that she’d be willing to see me afterwards to do genetic testing, just to confirm that it was nothing with me that happened,” says Costa, “and that was pretty much the last time I heard from my doctor.”

THE LAW IN ALABAMA: AIMED AT “UTTERLY ISOLATING THE PERSON WHO IS PREGNANT”

Alabama is among the 14 states in the U.S. with a total abortion ban, in which the procedure is illegal in virtually all cases, at all stages of pregnancy. Under the law, which passed in 2019 but only took effect after the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision in 2022, performing an abortion is a Class A felony with a punishment of up to 99 years in prison, plus a $100,000 fine. Today, the state is fighting to put even more strictures on reproductive care; in February 2024, an Alabama Supreme Court ruling granted personhood to embryos, temporarily halting IVF in the state.

At the same time, Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall has made criminalizing abortion care and gender-affirming care a crusade, and has threatened to use an 1896 conspiracy law to criminalize anyone who helps a pregnant person travel out-of-state to obtain an abortion or even gives a patient information about how to do so. “If someone was promoting themselves out as a funder of abortion out of state,” Marshall told a radio show in 2022, “then that is potentially criminally actionable for us.” He then promised to “fully implement this law.”

Doctors and clinics have taken action to try to protect Alabama patients—including by suing to block AG Marshall from what they see as muzzling health-care providers. Robin Marty, the executive director of the WAWC Healthcare clinic in Tuscaloosa and a plaintiff in the lawsuit, says these laws are aimed at “completely and utterly isolating the person who is pregnant, because if you cut them off from information and any sort of assistance, then you have essentially isolated her and forced her to do what you want. And let’s be honest, that’s what domestic abusers do: isolate and then abuse and force them into what you want.”

Tamara and Caleb Costa at their wedding. (Photo courtesy of Tamara Costa)

Tamara and Caleb Costa at their wedding. (Photo courtesy of Tamara Costa)

There are resources for pregnant people in dangerous health circumstances—notably, abortion funds, which offer financial and logistical assistance. But pending the results of the lawsuit, none in the state of Alabama are currently allowed to operate, and Costa wasn’t aware of out-of-state resources that can help. So she and her husband maxed out a credit card to cover the expenses for the last-minute, 580-mile trip to Chicago—flights, rental car, hotel, food, and childcare for Xavier back home.

In the week leading up to Costa’s Chicago appointment, she began feeling even sicker, but her doctors couldn’t see her again before she left—and so, feeling neglected, she decided just to wait. When Costa finally arrived at Planned Parenthood on August 16, the clinic performed a routine pre-procedure ultrasound, and the OB-GYN on duty, Dr. Erica Hinz, went in to see the couple as soon as she’d reviewed it. Costa, she said, was experiencing a partial molar pregnancy, along with her fetus’s triploidy. (The Meteor has reviewed Costa’s medical records from Alabama and Illinois and confirmed these diagnoses and treatment.)

Dr. Hinz remembers that Caleb, in particular, “was really surprised to hear that. No one in her care up until this point had even mentioned the word molar pregnancy to her, right?” recalls the doctor. “I was very, very angry and very, very shocked.”

“IT SHOULD NEVER HAVE GOTTEN THAT FAR”

Molar and partial molar pregnancies are potentially life-threatening diagnoses in which an abnormal placenta grows at an accelerated rate; it can also develop precancerous cysts. The condition is rare, but can cause long-term complications; the placenta can grow into the muscles around the uterus and invade the pregnant person’s other organs, and the associated hyper-metabolism can cause anemia, heart attacks, and multiple-organ failure leading to seizure and stroke. The cysts within a molar pregnancy can also develop into cancer. Dr. Hinz says it’s rare to see a molar or partial molar pregnancy progress as far as Costa’s, because “with ultrasound technology these days, we catch it pretty early, and that’s why it’s become not as dangerous—because you catch it and you treat it early…In her case, it should have never gotten that far.”

The Costas with their son, Xavier, at Christmas. (Photo courtesy of Tamara Costa)

The Costas with their son, Xavier, at Christmas. (Photo courtesy of Tamara Costa)

Dr. Hinz knew that Costa needed termination immediately, but because Planned Parenthood was not equipped to perform a blood transfusion if she needed one, she urgently arranged for Costa to have the procedure done immediately at a nearby hospital. “Honestly, if she were delayed any further, I think she would have had a much worse outcome,” says Dr. Hinz.

“I was in surgery within, like, an hour of being there,” Costa says of her hospital experience. “At that point, I think we were terrified.”

If any delay was so risky, why was Costa forced to wait two weeks and travel three states away to get the healthcare she so clearly needed? In Alabama, there is one highly restricted exception to the abortion ban: Care is allowed only if there is serious health risk to the pregnant person, and if two Alabama-certified physicians have confirmed the diagnosis. Costa’s partial molar pregnancy could have met the criteria, if she’d had that diagnosis earlier, and it’s possible she could have received care in the state.

But advocates tell The Meteor there is no guarantee that any Alabama facility would have been willing to perform the procedure. The wording of Alabama’s abortion ban is confusing, and according to Robin Marty, has cultivated an environment in which doctors can be terrified to act on their diagnoses. This has “destroyed the doctor-patient relationship,” says Marty. “Patients can’t trust doctors, either because the doctors are withholding information because they don’t want a patient to seek an abortion for ‘moral’ reasons, or they are withholding the information in order to protect themselves from any sort of potential litigation or ending up in jail. But on the other hand…doctors can’t necessarily trust the patients. I know that at our clinic, when we have patients who say, ‘Okay, I want an abortion, where can I get it?’, we can’t trust that these patients are actually trying to seek out this information and not trying to entrap us. So now the doctors can’t trust the patients, the patients can’t trust the doctors, and it has destroyed the confidence in the medical system at all. And so how are we supposed to deal with these extraordinarily life-threatening conditions when nobody can provide the information that needs to happen in order to make a good decision for the patient?”

The Costas’ experience reflected this fear-filled medical environment. Caleb Costa remembers that the doctors in Alabama were speaking in euphemisms. “They used the term ‘because of what’s going on,” he says. “‘In our current’ you know, ‘environment,’ there is not much we can do about it unless the heartbeat stops.”

“THIS ISN’T A DEMOCRAT OR REPUBLICAN THING…IT WAS ABOUT MY HEALTH.”

Tamara and Caleb Costa met at the University of Alabama through mutual friends. They’d both grown up in the same area of Kentucky, and were living quiet lives that revolved around work, family, and University of Alabama football. Tamara never thought she would have an abortion herself, though she didn’t think her beliefs should restrict how another person might feel. But this experience has changed them both, and the trauma is still fresh. “This isn’t a Democrat or Republican thing,” she says. “It was human rights. It was about my health.”

Of the laws that put her in danger, Costa continues: “It seems like they’re concerned with life, right? [But] the only person that was affected was me. They said the baby wasn’t compatible with life. The only life that was affected in this [situation] was the living one. The only one that could survive was me. And it wasn’t a priority…The state, by making the decision for me, was essentially saying Baby’s life was already gone—so we were both gonna die.”

“Everything I enjoy doing mostly revolves around my family,” says Tamara Costa, here with Caleb and Xavier. (Photo courtesy of Tamara Costa)

“Everything I enjoy doing mostly revolves around my family,” says Tamara Costa, here with Caleb and Xavier. (Photo courtesy of Tamara Costa)

It was “like she didn’t matter,” says Caleb Costa through tears. “Her life was at risk and it didn’t matter to anybody. She didn’t have an option here to get help, and that’s not fair to her… We were told we needed to terminate our child in Alabama, but Alabama said, you can’t do it here. Make it make sense.”

Back in Huntsville, Costa and her family are still dealing with the ripple effects of their ordeal. “Everything I enjoy doing mostly revolves around my family,” she says, including her three new siblings—foster kids whom her parents recently adopted. Tamara, Caleb, and Xavier have moved to another house, but they’re still paying off their credit card debt for their Chicago trip. They’re taking in every Crimson Tide game and watching their fantasy football brackets, but Tamara regularly sees a new local OB-GYN recommended by Dr. Hinz, because they have to monitor her blood on a weekly basis for any residual health risks from the partial molar pregnancy, which can continue to cause dangerously high hormone levels even after it’s treated. And, in fact, her levels of hCG—the hormones produced by pregnancy or cancer cells—still haven’t gone back down to zero.

But the couple is trying to both honor their baby and still move on. “I lost a part of me,” Tamara says. “So we were trying to figure out how we were going to keep that memory.”

“We decided we wanted something that was living and could grow.”

Late this summer, Caleb and Tamara bought a baby plant from a botanical garden in Huntsville. They tucked the ultrasound photograph into it, so that as the plant grows, “Baby is still growing with us.”

“We’ve just been trying,” Tamara says, “to heal the best way that we can.”

Julianne Escobedo Shepherd is a Xicana writer, editor, and co-founder of the music and culture publication Hearing Things. Her first book, Vaquera, about growing up Mexican American in Wyoming and the myth of the American West, is coming soon from Penguin.

Read more about the medical facts of Tamara Costa’s case here. And read more United States of Abortion reporting here.

Video Credits

Director: Amy Elliott

Editor: Dana Cataldo

DP: Brack Bradley

Camera: Jacob Cantrell

Audio: Neil Bagley

Producer: Annie Venezia

![]()

This film is a project of The Meteor Fund, and produced in partnership with Harness; with support from Pop Culture Collaborative.

WHAT IS A PARTIAL MOLAR PREGNANCY?

FEATURED STORY

Tamara Costa’s diagnosis, explained

BY MEGAN CARPENTIER

Tamara Costa faced two intertwined diagnoses: a partial molar pregnancy and a fetus with triploidy.

Molar pregnancies, explains Jennifer Conti, M.D., an OB-GYN and Complex Family Planning Specialist at Stanford Hospital, are “a very rare complication where the cells that will form the placenta go haywire.”

In both a molar pregnancy (one with no fetus) and a partial molar pregnancy (one with an abnormal fetus), the placenta includes cysts producing high levels of the pregnancy hormone hCG. Diagnosis usually occurs during the pregnant patient’s first ultrasound, and the only treatment is termination. Patients who aren’t treated early can suffer life-threatening complications, including sepsis, preeclampsia, shock, and uterine infections. The abnormal tissue can also grow into their abdominal muscles and/or cause cancer.

In addition, Tamara’s fetus had 69 chromosomes instead of the expected 46—a condition known as triploidy. It happens when one parent contributes two sets of their own chromosomes during fertilization, and can often also cause a partial molar pregnancy. Triploidy causes severe birth defects and usually results in miscarriages; the few fetuses that survive to term usually die within days.

“This goes to show how complicated and complex reproductive healthcare can be—and another reason why the doctor should be one making these decisions,” Dr. Erica Hinz, an OB-GYN with Planned Parenthood Chicago, told The Meteor.

Read more about Tamara Costa, and the laws in Alabama, here. And read more United States of Abortion reporting here.

Video Credits

Director: Amy Elliott

Editor: Dana Cataldo

DP: Brack Bradley

Camera: Jacob Cantrell

Audio: Neil Bagley

Producer: Annie Venezia

![]()

This film is a project of The Meteor Fund, and produced in partnership with Firebrand and Obstetricians for Reproductive Justice; with support from Pop Culture Collaborative.

New Tie, Same Old Misogyny: J. D. Vance's Failed Rebrand

By Shannon Watts

Since becoming the vice presidential nominee almost three months ago, J. D. Vance has taken almost constant fire for his long history of denigrating women, including comments on podcasts about the tragedy of remaining childless, the misery of women who work outside the home, and the duty of every post-menopausal woman to serve as stop-gap childcare for her family. As a result, Vance has the worst net favorability rating for any vice-presidential candidate in history and has become a walking meme for masculinity gone wrong.

Last night, in an attempt to shed that electoral albatross, we watched in real-time on live television as Vance attempted a calculated rebranding of himself as an ally to women everywhere.

From the glaring symbolism of Vance’s Barbiecore tie (instead of the traditional red tie Republicans typically wear) to his constant shoutouts to the women “very dear to me” (including his mother, grandmother and several anonymous women he claims to know who have been through some things), Vance worked hard to project feminine energy—someone who listens, who feels empathy, who might be open to changing his mind. But instead of embodying any of those things authentically, Vance’s debate performance came off like cosplay. This stab at a rebrand was as transparently pink-washed as his tie.

For me, Vance’s mask fell off a few times during the debate. It started when the two women moderators interrupted him for not following the agreed-upon rules, even cutting off his mic. Testy and defensive, Vance talked over them with the now-famous complaint, “The rules were that you guys weren’t going to fact check.” And even though he tried to camouflage it, Vance couldn’t disguise the misogyny that has underpinned his policy platform for decades. Moderator Margaret Brennan ended the exchange by quipping, “Thank you for explaining the legal process,” in a tone that struck a chord with every woman who has ever been mansplained to in a meeting.

When the issue of childcare came up, he implied he supported efforts to make it more affordable—even though he skipped the Senate vote for an expanded child tax credit. When abortion came up, Vance implied he didn’t support a national ban—when, in fact, he has stated publicly that he does. He told the story of a friend who needed an abortion in order to leave an abusive partner—but failed to mention the laws he supports would have instead prevented her from leaving.

But even more revealing, whenever issues like those were discussed, Vance made it clear that he sees those issues as only impacting women, as if they’re somehow untethered from any broad economic and societal implications or don’t also affect women’s partners, children, bosses, everyone. When he spoke about wanting the Republican party to become “pro-family in the fullest sense of the word,” he meant “making it easier for moms to afford to have babies.”

Even the new incarnation of Vance fails to understand that the “women’s issues” discussed during the debate are actually issues that impact everyone’s lives. The lack of high-quality, affordable childcare hurts parents, children, and employers alike. And restricting women’s rights restricts the freedom of all. We now live in a world where men are actively advocating for paid family leave and supporting abortion rights. But in his attempt to modernize his stance on these issues, Vance just wants to tell us about a woman he “knows.”

Despite Vance’s best efforts to rebrand, women wisely saw through his performance for what it was: performative. According to a CNN instant poll, after the debate Walz had the advantage among women, rising 18 points in favorability. The message is clear: We simply aren’t buying the “new and improved” Vance he’s trying to sell us.

Shannon Watts is an author, organizer, and speaker. She founded Moms Demand Action and recently organized one of the largest Zoom gatherings in history, mobilizing women voters for the 2024 Kamala Harris campaign. Her new book Fired Up is coming in 2025.

Shannon Watts is an author, organizer, and speaker. She founded Moms Demand Action and recently organized one of the largest Zoom gatherings in history, mobilizing women voters for the 2024 Kamala Harris campaign. Her new book Fired Up is coming in 2025.

How Shirley Chisholm Paved the Way for Kamala Harris

In a new oral history of the women’s movement, journalist Clara Bingham illuminates that and more

BY CINDI LEIVE

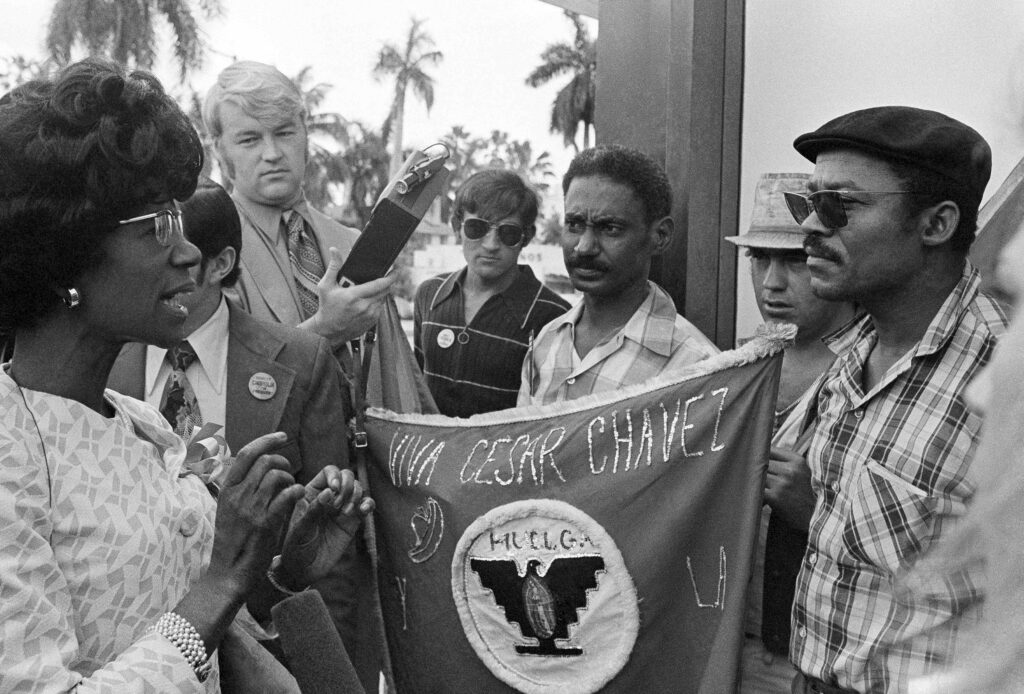

If, four weeks from now, Kamala Harris strides across a Chicago stage to become the Democratic nominee for president, it will be the first time a Black or South Asian woman has become a major party’s chosen candidate. But it will not be the first time a Black woman earned presidential delegates at the convention. That distinction belongs to former Congresswoman and 1972 presidential candidate Shirley Chisholm, who is one of the major players in Clara Bingham’s excellent and ridiculously well-timed new oral history, The Movement: How Women’s Liberation Transformed America, 1963-1973, out next week.

The Movement shatters the usual image of the Second Wave as being led solely by Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan, and—through Bingham’s interviews with 100 veterans of the movement, along with archival material—introduces the reader to trailblazers like Martha Griffiths, who got Title IX passed, and Rita Mae Brown and the swashbuckling lesbians of the Lavender Menace, who stood up to Betty Friedan’s anti-gay stance by swarming the stage at a NOW convention. (If it all feels like a movie, it’s worth noting that one of Bingham’s previous books, Class Action, was made into the movie North Country, with Charlize Theron.)

In other words, there’s a lot in the book. But given the news of the week, we had to start with Shirley.

Cindi Leive: This book is landing in the middle of a wonderful burst of energy around Kamala Harris. How do you see this, having been immersed in all things early '70s, but specifically the candidacy of Shirley Chisholm?

Clara Bingham: When Kamala Harris gave her acceptance speech back in 2020—when she and Joe Biden won the presidential election—she very specifically harkened back to women like Shirley Chisholm, who, she said, “fought and sacrificed so much for equality and liberty and justice for all…including the Black women who are often too often overlooked…but so often are the backbone of our democracy. I stand on their shoulders.” Those were the activists and intellectuals and organizers and leaders who paved the way for where we are today. And one of the most audacious of them was Shirley Chisholm.

Shirley Chisholm ran for Congress in 1968 from a newly created majority-Black district in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. And she defied the Democratic Party machine: The Black men who she'd worked with in the NAACP and different organizations in Brooklyn were upset with her for running and taking a seat from what would have been an African-American man. But because she rallied so many women voters and spoke fluent Spanish and basically knocked on every door in the district, she won. And she became the first Black woman member of Congress in January of 1969.

It's hard to imagine now the level of extreme misogyny and racism that Shirley Chisholm faced when she walked the halls of Congress in the first few months of her tenure. It was so horrific. In one incident, she was having lunch in the members’ dining room during her first days there. And she sat at an empty table. A Southern Congressman came up to her and said “You're sitting at the Georgia delegation table.” And he pointed to the New York delegation table across the room. She said, “I’m so sorry—I'll just finish here. You're welcome to join me.” But he refused, and she sat alone for the entire meal.

Another congressman from South Carolina, a pro-segregationist, would say “42,5,” every time she passed—meaning you're earning $42,500, the same amount that he was earning. It was an insult to this man that she was allowed to receive a paycheck that was the same number as his.

And there was another Southern congressman who would spit into his handkerchief every time she passed him. And so this is a classic Shirley Chisholm reaction: She brought a handkerchief, and when she passed him and he spat into his handkerchief, she turned to him and said, ‘Oh, you might need another one!’ And handed it to him.

She had this ability to face down the misogyny and the racism that she put up with. And I think that is a lesson for Kamala Harris because she's already the target of a barrage of misogynistic and racist attacks. We’re in a different place two generations later… except for one thing, we just lost our constitutional right to an abortion. And so that puts Kamala Harris right into the bullseye of what women need going forward.

Can you tell us a bit about Shirley Chisholm’s presidential run and the delegate votes that she received?

So Shirley Chisholm gets elected to Congress in 1968 and just four years later decides that she's going to run for president. She doesn't ask anybody for permission. She doesn’t ask anyone in the Democratic Party. She doesn't ask the Black Congressional Caucus. She doesn't ask the National Women's Political Caucus [which] she helped found.

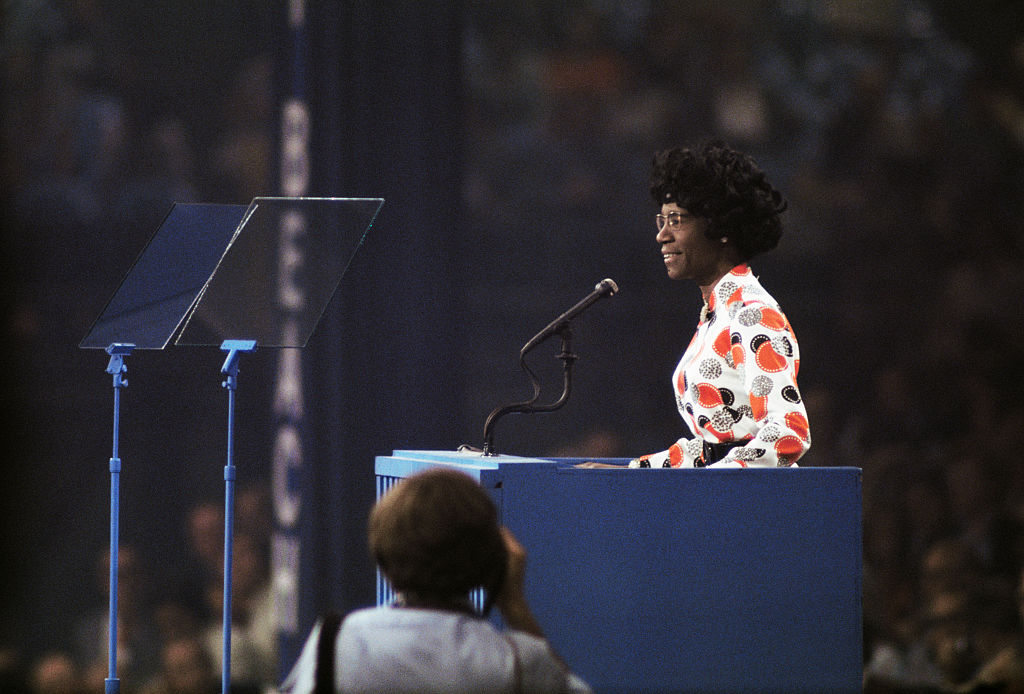

She and everyone else knew that she had no chance of winning. But it wasn't just a symbolic race—it was a motivational and inspirational race. She realized that the white male Democrats were not speaking to a huge swath of potential American voters. They were not speaking to the youth vote—and at the time, in 1972, 46,200 U.S. soldiers had died in Vietnam. We were at the height of the Vietnam antiwar movement. We were at the height of the Black Power movement. We were at the height of the hippie counterculture. And also at the early but heady euphoric moment of the women's liberation movement, which came out of all three of those other movements for social change. So she says, in her iconic speech at the Brooklyn Concord Baptist Church in January of 1972, these famous lines: “I am not the candidate of Black America, although I am Black and proud. I am not the candidate of the women's movement of this country, although I am a woman and I'm equally proud of that. I am not the candidate of any political parties or fat cats or special interests. I stand here now without endorsements from many big name politicians or celebrities or any other kind of prop….and my presence before you now symbolizes a new era in American political history." And it did, because she engaged with people who had felt alienated from the mainstream political process. She held huge rallies all over the country, although she was only on the ballot in eight states.

In the end, at the convention in Miami, she got 152 delegates—which is not many, but it's some—and she became the first woman in the Democratic Party to have her name placed in nomination. That was such an important historical landmark. And when she then walked into the convention, she realized that even though she’d lost, she'd made a difference. She wrote, “I had felt that someday a Black person or a female person should run for the presidency of the United States, and now I was a catalyst of change.” That's what she was…and that's what Kamala Harris is now. In our new world.

You mentioned the other movements happening at the time—I'm not sure if it's fully appreciated how much the civil-rights movement helped the birth of the quote-unquote women's movement.

So many of the women—almost every single woman I interviewed—had been involved in the civil rights movement. And Black women who were on the forefront of the civil rights movement—women like Eleanor Holmes Norton, Pauli Murray, Florynce Kennedy, Frances Beal, the list goes on—were the legal architects and the moral architects of the second wave feminist movement. And that is something that I think people don't understand. The leaders of this movement were women who came right out of the civil rights movement, and they were women who understood racism and the connection between racism and sexism. It took a lot of white women longer to get it.

One example I love is that the white women who were at Newsweek were beginning to realize that the system at that organization was completely discriminatory of all women. When they started to realize that maybe it was illegal for the masthead at Newsweek to have all men at the top and women at the bottom, they went to the ACLU and met Eleanor Holmes Norton. She was fresh from Mississippi—she’d gone down to help get Fannie Lou Hamer out of jail. She had to teach the women at Newsweek what discrimination was! Because so many of them had gone to Seven Sister colleges and were privileged and educated, they thought discrimination was just a race issue. Eleanor realized their case was classic discrimination—she had to have seminars with so many of the white women who were working in Newsweek to explain to them, this is discrimination, and this is how it works.

You talked about the opposition that Shirley Chisholm was going up against, and it makes me think about what Kamala Harris is going up against in Trump, and his exaggerated white masculinity—the way he has embraced the Hulk Hogan of it all. Does the opposition now feel even fiercer than it did then?

Shirley Chisholm and a lot of the early feminists had to face a Neanderthal-like sexism that even today, in Trump MAGA world, is hard to imagine. …Now we have Trump, who has this toxic masculinity and is a strongman—and is such a throwback. But these guys were so afraid of change. When it came to the fight over the ERA in 1972, there was a North Carolina Senator, Sam Ervin, a Democrat, who was born in 1896. He was born before suffrage! He was 24 when women first got the vote! And in 1972, he gave this crazy speech, where he said, “I am also constrained to offer this amendment because of my realization that my life has been made happy by a wife who has stood beside me for many years and has faithfully performed all of the obligations devolving upon her as a wife and mother.” He quotes from Genesis. And he [and his peers] were the first men in the world who had to contend with women forcing them to give them their rights. They had to relinquish those rights: The ERA passed with flying colors in both the House and the Senate—it was a bipartisan victory, which is really hard to imagine today.

But it didn’t pass. That’s one of the heartbreaks of your book.

I stopped the book in 1973, which really was one of the high points of the movement. Roe v. Wade had happened. The National Black Feminist Organization had launched. Billie Jean King beat Bobby Riggs in the Battle of the Sexes. Title IX had been passed, the ERA passed. After '73, Phyllis Schlafly came on to the scene. And of course we all know that in the end, in her demonic and brilliant way, she managed to stop the ERA from being ratified by the states. If the ERA [were] the law of the land…I think we would be able to use it legally to argue for abortion rights.…And we can't make that argument now, because we lost the ERA. It's devastating.

You’ve spent years immersed in this history. Are you encouraged or discouraged by it?

Oh, I’m so encouraged!…This movement changed so many really ingrained, deep-seated customs that for thousands of years had placed women in a position of being second-class citizens. And so if you think of it, these men like Sam Ervin who were having to witness this change—it was completely rocking their world.

Trump is a modern iteration of the same thing. But you can't put the genie back in the bottle. You know, he wants to—so do Brett Kavanaugh and JD Vance. They want to put women back, but that's just never going to happen. It's impossible.

Cindi Leive is the co-founder of The Meteor, the former editor-in-chief of Glamour and Self, and the author or producer of best-selling books.

Believe Children.

What we should really be saying about Alice Munro

By Julianne Escobedo Shepherd

Last weekend, Canadian writer Andrea Robin Skinner wrote an intensely personal op-ed about her sexual abuse at the hands of her stepfather—and about how her mother had protected the abuser. Though the violence began when Skinner was 9, she found the courage to tell her mother when she was in her twenties. But her mother “reacted exactly as I had feared she would," Skinner writes, "as if she had learned of an infidelity.” Skinner went on to report her stepfather to the police (he got two years' probation) but never reconciled with her mother before her death. It's a horrible story of sexual abuse and betrayal—but the thing that got the most attention was the name of Skinner's mother: Alice Munro, the celebrated novelist and 2013 winner of the Nobel Prize for literature.

The media response thus far has been primarily about Munro's legacy, with a procession of op-eds about what to do with her books and whether her writing indicated that she was the kind of person who would ignore her daughter's pleas. We've been having these types of conversations for years—the "can we separate art from artist?" conundrum—about cultural icons from Woody Allen to R. Kelly to Picasso. And yes, that’s a mildly interesting question…which also distracts from the most important issue here: Why on god's green earth are adults still dismissing children when they tell them, with an unimaginable amount of courage, about being sexually abused?

Skinner's story is important not because of who her mother is, but because it illuminates disturbing truths about how child sexual assault is dealt with—or not—particularly when family ties seem to complicate the simple act of protecting children. "It seemed as if no one believed the truth should ever be told, that it never would be told, certainly not on a scale that matched the lie," Skinner wrote.

Skinner’s experience is devastatingly common: RAINN estimates that one in every nine girls and one in every 20 boys experiences some form of child sexual abuse before they're 18, though some studies say the statistics are even higher. The ripple effects are lifelong: Once a child experiences sexual abuse, they're much more likely to experience PTSD, depression, or develop symptoms of drug abuse, per RAINN. And ninety-three percent of these children know their abuser, whether a family member, teacher, or some other person in authority—a violation of trust which makes it that much more difficult for them to report the abuse, particularly if their abuser has made threats against other loved ones, a common grooming tactic.

When the abuser is a family member, in particular, the dynamics get even more complicated, even though they hypothetically shouldn't. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry emphasizes that when a child reports their own abuse, it's important for the adult to remain calm and refrain from making judgmental comments, and to assure them they are not to blame—two crucial kindnesses Skinner writes that she wasn't afforded. And though there aren't hard statistics available about the percentage of children who report abuse but aren't believed, judging by the amount of first-person testimonies on the internet, it's unfortunately common. Even Ellen Degeneres experienced this—she was abused by her stepfather and her mom disbelieved her. (Degeneres's mother believes her now, thankfully; in 2019, she released a statement that read, in part, "If someone in your life has the courage to speak out, please believe them.")

We know what some people say: that not every claim is true. And many remember so-called "false memory syndrome"—although that’s not a term or concept officially recognized by reputable psychiatric sources such as the DSM-IV—and the "Satanic day care" panic of the 1980s and '90s, in which children did in fact accuse daycare teachers of mass abuse. (Most saw their convictions overturned.) But the fact is that these instances were and are extremely rare; in fact, like rape, childhood sexual abuse is grossly underreported, with one study identifying that half of childhood abuse survivors never tell anyone, even after they are adults.

That makes what happens when young survivors do tell someone so crucial. “Don’t let your natural and understandable feelings of confusion and doubt override the fact that the perpetrator is always at fault,” writes the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN), in its very helpful guide. “If, in the heat of your own pain and distress, you accuse your adolescent of betrayal instead of acknowledging that your child was the victim, he or she may begin to experience dangerous—and potentially damaging—self-doubt.” Reading the NCTSN’s materials, you also understand that given the frequency and prevalence of childhood sexual abuse, it's possible that the person being told has their own traumatic history with abuse, which can complicate their reaction.

Skinner wrote her piece after years of experiencing the ripple effects of being both abused and disbelieved; she began slipping in school and struggled with bulimia. But while her trauma followed her well into adulthood, as it does with many survivors, she eventually got professional help. It's never too late to do that, and there are lots of specific resources for adult survivors, including organizations, like Hidden Water, which follow a restorative justice approach to healing.

What else might help? Erin Merryn, a survivor and children's advocate, has some answers. After being abused as a child—first by a neighbor, then by a family member—she has since spent the last 15 years lobbying legislators around the country to implement Erin's Law, which requires public schools to teach prevention courses to children in school through 12th grade. (It has been adopted in 38 states, with more on the way.) Reporting abuse might be fraught, but signaling to a child that they're being protected from further harm is more important. Most crucially, the child must be believed and treated with gentle care, particularly if they're expected to develop a healthy adult life. And that matters more than any one writer's legacy.

If you or someone you know needs help, contact RAINN here or at 1-800-656-4673.

Julianne Escobedo Shepherd is a writer, culture critic, and editor in NYC. Her first book, Vaquera, about growing up in Wyoming and the myth of the American West, is forthcoming for Penguin.

Voguing for Trans Liberation at New York's Most Brutal Jail

Jordyn Jay takes us inside Rikers Island for a ball

By Mik Bean

New York’s Rikers Island is one of the nation’s most notorious jails, where incarcerated trans people are treated especially inhumanely. But last Thursday, it was also the site of the second annual vogue ball for trans incarcerees. “We wanted to give our incarcerated siblings more opportunities to show their dedication to the culture and the art form that is ballroom,” says Jordyn Jay, founder of Black Trans Femmes in the Arts (BTFA), which organized the ball and has funded and supported Black trans femme artists for five years now. “We are there to celebrate them and to bring them joy in this very dark, cruel system of mass incarceration.”

I spoke with Jay about the Rikers ball and other radical acts of hope.

Mik Bean: Shows like Pose and Legendary and Beyoncé’s RENAISSANCE tour have brought ballroom culture to a wider audience. But its history is one of radical celebration in the face of violent criminalization. Why was it important to bring ballroom back to Rikers?

Jordyn Jay: So I want to be clear that the idea [for the ball] came from the folks detained and incarcerated at Rikers Island, and that is in line with the history of ballroom. Vogue began in Rikers Island from folks who were incarcerated there, referencing images that they saw in magazines. That was the only connection they had—not only to the outside world, but to their femininity, through expressing themselves by mimicking the models’ lines and shapes.

Modern ballroom culture as we know it was started [in the 1970s] by Crystal LaBeija, as a Black trans woman’s dream for what society could be. She created an ecosystem in which trans beauty and bodies were celebrated. We are grateful to the people who’ve taken ballroom to a global stage, but there are also consequences when you open up a safe and sacred place to the world. A lot of the femme queens—which is how we refer to trans women in the ballroom scene—have noticed that there’s been [little] appreciation for us as individuals despite the fact that we are, historically and currently, what people come to see.

So many ballroom legends and icons have passed through Rikers Island because of the criminalization of trans bodies and what trans people have to do to survive. It’s especially amazing that we’re able to bring formerly incarcerated trans women to work with currently incarcerated trans women and celebrate ballroom culture in this space during Pride—and to do so with an abolitionist lens.

Can you explain what you mean by an “abolitionist lens”?

It’s so important that this ball is happening during Pride Month because pride and carcerality have a linked history. There would be no Pride Month without police brutality—without mass incarceration.

Rikers is a global symbol of the oppression of America’s mass incarceration and policing systems. So when we bring the arts and bring pride into that space, it is in itself a protest. We are hoping that by bringing the arts into Rikers…that this revolutionary, transformative energy of the arts is able to carry [incarcerated people] forward.

Can you describe the feeling of being at the Rikers ball?

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the darkness that we feel as we travel onto the island, as we navigate security, as we walk down the halls and folks are forced to stop and put their heads against the wall and their hands behind their back. It is a stomach-sinking feeling. But once we enter that room and see the faces of the folks who we came to support, there is so much empathy and so much joy.

It almost feels wrong to say that our visit to Rikers was fab, but truly, that’s the best way I can describe it. I think we came in with the intention of bringing joy and excitement to the women who were detained. We got just as much excitement as I hope that we gave them. The energy—the femme queen energy in particular—was just so palpable in the room. There was so much joy from the moment that we walked in.

Being trans is itself an act of creation. Can you share more about how you see that link in your own work?

So many of the organizing bodies that center around Black trans folks are geared towards houselessness, HIV/AIDS, and fighting [anti-trans] legislation. These things are really crucial, but [they] aren’t focused around joy. It’s a lot of talk of loss and trauma, and that really took a toll on me in the early days of my transition.

So I wanted there to be a space where we could not only come together and center joy, but also express ourselves through the arts and have the resources to do that. [Through grantmaking and production support, BTFA fosters the careers of artists like Kiyan Williams, recently celebrated for their work in the Whitney Biennial.] There are so many of us that have never had someone to sit down and touch our hand and say: “You can do this. I believe in you. I want to see your art in the world. I want to hear your voice in the world.”

Trans people have to create ourselves in a world that tells us that we shouldn’t exist, and that is the ultimate artistic expression. We’ve already broken this gender binary and this understanding of how people are able to exist in the world, so there’s really an endless flow of possibility. As I was moving through my transness and meeting new trans people, every one of them was an artist in their own way. When people engage with art created by Black trans femmes, it allows them to understand us as human beings—and to see themselves in trans people.

What is the future you envision for Black trans femmes artists?

BTFA’s vision statement is that we envision a world where Black trans femmes can create without limitations. The headline is always “Black trans femme artists,” and I think that’s wonderful for representation’s sake. But my question is: At what point do we as artistic scholars challenge ourselves to view this art as art and critique it as such? When we start to engage with the actual work, there’s so many more important conversations that can be had.

It’s just a pleasure to be able to watch this program expand. It’s in line with all that being a femme queen is: We break barriers down and we disrupt systems. Our form of protest in this space is joy, is laughter, is cheering. We hope that they all felt the power and energy behind this too-brief but very beautiful moment that we got to share.

Updated 6/19/2024: A previous version of this story incorrectly referred to Rikers Island as a prison. Rikers is a jail facility, however, the island where it is located is a "prison island." We have amended our language and regret the error.

Mik Beanis a social media strategist with a master’s degree in journalism. A former advisor and content producer for organizations including The Washington Post, Instagram, and AIDS Healthcare Foundation, Mik specializes in political science and gender theory.

Mik Beanis a social media strategist with a master’s degree in journalism. A former advisor and content producer for organizations including The Washington Post, Instagram, and AIDS Healthcare Foundation, Mik specializes in political science and gender theory.

Have We Been Thinking About Ambition All Wrong?

Samhita Mukhopadhyay charts a new alternative for work life (beyond the girlboss or tradwife)

BY CINDI LEIVE

Samhita Mukhopadhyay has spent her career doing two things brilliantly: being a serious boss (she helped run the newsroom at Mic and served as the executive editor for Teen Vogue), and being a serious feminist (she was a founding editor at the late-'00s site Feministing). Those dual experiences—sometimes, but not always aligned—make her the perfect person to answer the question: What does, and what should, the future look like for women in the workplace? And can you be a boss and a feminist at the same time?

Those aren’t simple questions; work, after all, is a place with its own needs, bottom line, and occasional drudgery. (There’s that old expression: If work were that pleasant, the rich would keep it for themselves.) I’ve written and talked about the subject of women and work plenty, and I still don’t have answers.

But Samhita’s new book, The Myth of Making It: A Workplace Reckoning, does. Full disclosure, Samhita is a friend and colleague: We both worked at the media company Condé Nast, although we didn’t know each other there; now, we work together at the ever-so-slightly-less-glossy outlet you’re reading right now. (We think of it as The Devil Wears Sweatpants.)

She began writing this book during the pandemic, which was—you might remember?—a stressful time for working women. We started there.

Cindi Leive: When you started to write this book, there was a lot of gleeful dancing on the grave of the girlboss. Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In, which had been a bible of early ’10s feminism, suddenly seemed very outdated—women were realizing that if you’re underpaid, overworked, and don’t have child care, no amount of leaning in was going to fix that. But you also didn’t want to chuck the whole idea of ambition. What was the problem you were trying to solve?

Samhita Mukhopadhyay: Woman after woman in my life who were extremely ambitious in their careers were starting to question that ambition because they weren't living the life that they thought they were going to live. They weren't finding the happiness or the meaning or the purpose, and they were struggling in their personal lives.

But it felt very easy [for society] to say, “Women's ambition is dead. We should have never let you have that education and have that career. Because look what it's done to you now. You're burned out; you're tired; you're a bad mother.”

It felt like there was no space for us to be like, I'm actually in between all of these narratives. Like, I'm not going to become a tradwife, but the way we’ve been taught about ambition—pull yourself up by your bootstraps, work as hard as possible, girlboss your way to the top—that narrative is also not working for me. I'm going to do something more impactful. And I wanted to explore that.

You just referred to the kind of other side of the spectrum from the girlboss—the tradwife. Can you define that term?

There has been a trend of [female] influencers declaring that they are no longer going to pursue career ambitions and they're more focused on their family and their husbands. It's a trend that's hard to actually quantify—it gets a lot of press coverage because anything that's critical of women's ambition gets a lot of press coverage. All the women in my life have to work! But I think we are fascinated with the idea of putting women back in their place.

That's where this question of limited narratives comes in, because wanting a soft life or embracing more balance in your life should not come at the cost of women's progress. A happy life with dignity should not come at the cost of you being able to pay your bills, right? We should be able to do all of that.

But work has become so inhumane, and we conflate a rejection of capitalist hustle culture with rejecting the progress of feminism. The problem isn't that women are ambitious and they want to work. The problem is that we have a society and workplaces that can't support [those ambitions]. Especially for mothers.

One of my favorite lines in the book is when you say that girlboss culture sold the idea that capitalism and feminism could have a totally functional baby. Do you see those things as totally at odds? Is there no place in feminism for trailblazers like Ursula Burns [the former CEO of Xerox] or Indra Nooyi [of Pepsi]—or even what you were doing at Teen Vogue?

I think the connection is not as…fluid as we had hoped. [laughs] Ursula Burns and Indra Nooyi, while they are groundbreaking, they are exceptions, right? They're often peddled to us as “You could do this, too!” And the reality is, most of us actually can't do that. It's impossible for one person to fix [the system]. It's collective action that's going to bring change. It's not necessarily that having women in these roles isn't valuable. I just don't think it's been as successful as it’s been sold to us.

You say that you don't have all the answers—you write that “this is not a how-to book.” But I’m going to push you for a little advice anyway. What’s the best way to be a better—and maybe more feminist—boss? You’re really good at it.

One of the things that I always think about is: What does it look like to have my ambition be connected to the ambitions of the people that work for me? So that I am a unit with them, and that no matter how I move forward in the workplace, my moving forward is connected to their moving forward. The research is showing that women are actually better at doing that, too: They're better at creating inclusive work environments where people feel seen. So what does it look like to shift the focus and say I will do everything I can to support my employees? Within reason, I mean; at the end of the day, we all have to get our jobs done. In some environments, profit’s gonna matter, productivity is going to matter. But I do think that as managers we can say to our employees, I will always advocate for the biggest raise for you. I will always advocate for you to get the training that you want. And for you to be able to take care of your family and to take care of yourself.

You also say that bosses need to be better about admitting mistakes. You tell a really vivid story in the book about being called the wrong name in a past role…

I was sitting in a high-level meeting and the person leading the meeting called me by the wrong name—the name of another South Asian executive at the company. It was a complicated moment: Technically, I wasn't supposed to be in that meeting; I was there in lieu of my boss. The other executive was supposed to be in the meeting, and she was not there, so it was the perfect storm for a mix-up. In the moment I was like, that couldn't possibly have just happened. But the person next to me was like, “No, that happened.”

The way you write about it, it sounds as if it was upsetting to be called the wrong name. But equally upsetting was the way it was handled, where nobody actually admitted to having done what they had done.

I did feel upset that it had happened. I already felt so uncomfortable in that room around all of these senior people. And that kind of confirmed for me that I really shouldn't be there. But—let people make mistakes, right? I use the wrong pronouns sometimes; things like that happen. I don’t think that it means that the person [making the mistake] is vicious or angry or inherently racist.

But everybody made a big deal about it, and I noticed that the focus was much more on this mistake rather than all of the forces that create a mistake like that: lack of representation for women of color in leadership roles, or lack of effective diversity and inclusion programs that actually address unconscious bias. There’s research on this: They call it the same-race effect or same-race bias; when you have not been exposed to a variety of people in another race, you tend to confuse them for each other. There's also a power dynamic here: People in management positions tend to do it more often than employees, because employees have to be very aware of the identity of the people that are managing them. And most managers are predominantly white, so you can see how that plays out. It was the conflation of all of those things in that moment. But we focus so much on the question of, “Oh, is that person racist or not racist?” And then that becomes the question, rather than how we create a situation where people of color can work with dignity.

So if someone does make a mistake like that, what is a better way of trying to deal with it?

First and foremost, by acknowledging the mistake and saying, “I am so sorry. I'm so embarrassed. Of course I know who you are. My mistake.” If you realize in the moment, do it in the moment. I’ve had to do that: “I’m sorry, I know that's not your gender pronoun, let me do that again.” It's a little awkward, but it goes a long way toward making the person feel seen and heard. And if you don't realize in the moment, admit that it happened and that you are committing to do better next time. I don't think people realize how far those apologies actually go! I really felt like I did something wrong, like, Oh my God, how dare I be here, and be Indian! So an apology helps.

There is this huge opportunity right now for leaders to really take seriously the question of how to make everybody feel included or confident or empowered at work. If you’re truly invested in diversity and inclusion, you can get to know every single person that works for you. And treat everyone with the recognition of: We know who you are, and we know what brings you here.

You’re talking about the importance of a feeling of belonging at work. And one of the most moving stories in the book is when you get a bad performance review and you go out to sob on a bench outside. You're in your 30s and you feel ashamed of being so upset, and you later realize that it’s because the review taps into this preexisting feeling that maybe you never belonged in that workplace to begin with. Is belonging a fundamental thing for us to think about as we redefine ambition?

Absolutely. The statistics around how lonely people feel at work are quite devastating, right? It's especially true for women and people of color, who often feel very alienated in the workplace. When we're taught that we don't belong somewhere, it's very hard to do your best work or to even show up. In my own case, my own struggles in early schooling—and bad grades—really impacted what I thought was possible for myself. And so I always felt like I was faking it, like I actually didn’t deserve [success]. I think that a lot of people struggle with that at work. And I think that working from home has caused more alienation, especially for young women, because so much of what I learned at work was being mentored by older women. And that piece is really missing right now: the feeling that someone’s invested in your career and working to help you feel included. That’s one reason people are quiet-quitting; they're not feeling like they're part of something bigger.

I want to ask you how all this ties into social change. A fascinating study just came out showing that those “lean In” messages can actually lower women's motivation to protest gender inequalities at work. Did that surprise you?

It did! I could see that individual-style “workplace feminism” has not been effective, but we still need it. I mean, I'm not going to stop telling young women that they should ask for more money!…But what I found so interesting is the finding that when you internalize the idea that your success is dependent on your behavior alone, that disconnects you from a broader story about gender justice. That research is a missing link: We have isolated women with this attitude of “to have it all, you have to do it all.” And then that internalization has blinded us to the way structural realities are impacting us.

The alternative to what we’ve been doing is that we actually come together and rise up—rise up together.

“What We Do in the Streets Is a Way of Grieving”

On the fourth anniversary of the Black Lives Matter uprisings, author Prentis Hemphill offers a new way of looking at things, and what's next.

BY REBECCA CARROLL

Four years after George Floyd’s murder, I realized that I simply do not have it in me to write another piece about Black pain, patterns and cycles of violent racism, and the endless trauma that continues to course through our bodies and bloodlines. I’ve literally written hundreds of them. I’m tired. And it feels like nothing ever changes.

But years ago, I asked the late civil rights activist Julian Bond how he managed to stay hopeful in the face of what often feels like little progress. He said, “There are enough victories to keep hope alive, and that’s what activism is.” And so I keep looking for the victories, which lately has meant having conversations with folks, particularly younger folks, who are deep in the work with fresh eyes, bright minds, and open hearts. Prentis Hemphill is one of those folks, one who, right on time, has a new book out called What it Takes to Heal: How Transforming Ourselves Can Change the World. The author, therapist, and organizer spoke with me about the power of collective grief, finding the small openings of possibility, and the necessity of visual longing.

Rebecca Carroll: Your book begins, “When Trayvon Martin was killed, I had just started working at a community mental health clinic in Los Angeles, one of three Black therapists on a staff of nearly fifty.” How do you hold the grace to write about the fact of yet another Black body being killed?

Prentis Hemphill: The only way is by being in community that can feel, and grieve, and strategize, and celebrate. That’s the only thing that actually sustains me. I can only face things because I’m held, and because I’m also holding. Every time someone in our community is killed in this way, it reverberates. We have memories of people in our communities that were killed that way, people in our families that were killed that way. The ongoing violence against Black people, it reverberates through all of our grief and all of our pain. Even though we as a people have made it this far because we reach for each other, I think we also try to—and have to—shoulder more than is ours to bear.

I was just having a conversation with a dear friend and organizer, Malkia Devich-Cyril, about how our grief has been criminalized and that part of what we do in the streets is a way of grieving. But because of what is projected onto us as Black people, our actions are never read as grief rituals; they are often labeled as violent, disruptive, inconvenient.

By “what we do in the streets,” I take that to mean being collectively loud, actively creating movement culture, and just being Black—does it matter whether we know that we are simultaneously grieving?

That’s a great question. Having been at a lot of protests and on the ground in so many different places over the last 15 years, I think a lot of people know that their grief is present. But there’s the connective piece—the collectivizing of the experience of “I feel this pain”—that we don’t talk about. We know it’s our grief, but we also narrow it, because that’s what we’ve had to do to get by. I am interested in starting to unlock how [our grief] can be bigger, because that’s the truth of what we’re holding.

You wrote about not being able to know how Harriet Tubman learned to trust her dreams. How did you learn to trust your dreams?

I always felt entitled to my life, to an authentic life. I always felt like, if God made me, then I’m all right. I can see the way that human beings create rankings and structures to take you away from the truth of it all, but there was always something in me that wasn’t confused. I would like to say I was just born with that, but I can feel my grandmother in it, I can feel my great-grandmother in it—[this notion] that the world is telling one story, and I feel something truer. I think it means a lonely path for a lot of people who refuse to dim their light. Sometimes, we have to dim our lights for the sake of safety, but for the most part, I cultivate that light in me. I think life wants to express itself.

There’s this one really striking line from the book: “It’s hard to heal when you're still being hurt.” How do we lead our way through healing while we’re still being hurt in all ways?

When we get hurt or experience trauma, when we don’t have space to process it, some part of us gets locked in that moment, and we’re replaying and responding to it all the time. When I work with people, [what makes a difference is] the recognition that in each moment, there is a choice. It may not be an ideal choice, but when our stories hold us captive, we’re no longer able to perceive the choices in this moment. It’s the work of finding the very small openings where something else might be possible. That’s a part of healing. That’s what Harriet Tubman was able to do. She was like, “You have me in this world, but now, I can see that there’s a little opening here. I can see a friend here. I can see a path here.”

It feels like we’re talking about trauma on a national level in ways that we haven’t before—what do you think is on the other side of that conversation?

I’m curious about trauma as a human phenomenon—and knowing this, how then do we structure our societies, our communities? What would we do if we knew that healing was important? I bet we would construct the world in a different way, and it wouldn’t be based as much on exploitative and violent tendencies which we’ve normalized at this point. I’d rather we normalize something else.

In the book, you wrote that visions are rooted in longing—can you say more about that?

I’m not a real churchy person, but “faith without works is dead” is something my grandmother would say all the time. We get sold visions for our lives, sold visions for who we are supposed to be. It’s necessary for us to reactivate that kind of looking around that, again, Harriet Tubman was able to do—looking through the cracks, looking underneath, and activating our own strangeness. No matter what happens tomorrow, we are facing compounding, complex crises. I hope that [my book] is a tool, something that accompanies people through the changes and challenges I think we're all facing.

My name is Prentis, which means student. I feel like my role is to tenderly offer the questions that I feel need to be posed in this moment. I don’t position myself as an authority. I position myself as someone who is learning, someone whose role in community is to pose questions—and to keep us close as we try to answer them.