She Fled Fear—and Found It Here

A woman who escaped danger in Afghanistan reflects on what life is like under ICE.

By Lima Halima-Khalil

I drop my three-year-old daughter off at library classes every morning. The library is two minutes from our home in Ashburn, Virginia. Each time, the same thought crosses my mind: Do I have my ID on me? Will my driver’s license be enough if I am stopped?

It is highly unlikely that I will encounter ICE on a two-minute drive to the library. Ashburn isn’t exactly an ICE hub. And yet my fear is constant, embodied, and real. And by the way, I am an American citizen.

I grew up believing America was a mighty country, one so powerful that the rest of the world stood intimidated by its strength. When I first came to the United States in 2006 for an education program from Afghanistan, a country still at war, the vastness of this place revealed itself not only in its size, but in the generosity of the people I met. After that, America became a place I always returned to. I have been part of the American education system since 2010, returning several times for various degrees. I’ve witnessed multiple presidential elections and participated in the most recent one as an American citizen myself.

But after all these years, one lesson about my new home stands out above the rest: This country is led, shaped, and sustained by fear. Outside this country, nations tremble at the military and economic power of the United States, but inside it, people live as though danger is always lurking.

Fear raises money and sustains campaigns. Fear keeps people glued to screens and locked into cycles of outrage. Fear sells guns, justifies surveillance, expands borders and prisons. Much of this fear is not grounded in lived reality but manufactured and amplified by politicians who rely on it to govern. Fear spills into kitchens, sidewalks, classrooms, and moments meant to be ordinary and human.

One of the most brutal tools in this ecosystem right now is ICE. Raids, detentions, and aggressive enforcement practices operate not simply as immigration policy, but as a mechanism of fear, reminding entire communities that their sense of belonging is fragile and conditional. ICE does not need to be everywhere to be effective. The possibility of its presence is enough.

This pervasive fear turns ordinary routines into sites of anxiety. I remember hesitating before offering to share our Thanksgiving meal with our nosy white neighbor, suddenly gripped by thoughts I never imagined I would carry. What if he calls the police on us and claims I was trying to poison him? What if kindness itself is misread as a threat, or hospitality as danger?

Afghans discovered how quickly they could become the “other,” regardless of their sacrifices, their loyalty, and their love for this country.

I recognize these impulses, because fear is not new to me. I lost my school, my home, my loved ones, and eventually my country because I wanted freedom from fear. Millions of Afghans had believed in democracy when America promised it to us for 20 years, until the United States withdrew from Afghanistan in 2021. We voted, we hoped, we worked alongside our American partners for a shared dream, but that freedom never came. In 2020, when my 24-year-old sister was killed by the Taliban in an IED attack in her car, that truth became undeniable. I understood then that Afghanistan was no longer safe, and that realization is what led me to come to the United States permanently.

When the Taliban returned to power in 2021, many Afghans, including members of my own family, were evacuated and brought into this country by our American allies. They arrived in this country under extremely harsh circumstances, believing they would find dignity, safety, and a chance to contribute. Instead, they discovered how quickly they could become the “other,” regardless of their sacrifices, their loyalty, and their love for this country.

I was reminded of this again in November of last year, after a man from Afghanistan, who had been trained and worked for the CIA in his country, shot two National Guard members in Washington, D.C. Overnight, an entire community began to be seen, once again, as terrorists. Instead of a careful and humane conversation about mental health, trauma, or resettlement failures, the Trump administration halted all immigration from Afghanistan and pledged to re-examine green card holders from 19 countries. Afghans, many of whom fled the very forces America claims to oppose, were once again forced to prove their innocence.

This is how fear functions. It identifies a moment of tragedy, strips it of context, assigns collective guilt, and converts pain into political currency.

For a long time, I believed that fear in this country belonged primarily to people of color, that violence was uneven, predictable, and racialized. Then the killings of Renée Good and later Alex Pretti shattered that belief. They forced a painful realization that in today’s America, no one is safe, not five-year-old Liam Conejo Ramos, not women citizens like Dulce Consuelo Díaz Morales and Nasra Ahmed, not elderly citizens like Scott Thao or longtime residents like Harjit Kaur, not white Americans, either.

Lately, I have felt fear settle into my own body in a way I did not expect. I realized I had been going to sleep holding fear, living with the same quiet dread that so many people here carry without ever naming it. One night, I caught myself thinking, almost with disbelief: Congratulations, Lima, you are an American now.

But it does not have to be this way. Americans deserve more than this constant weight of dread, clinging to them like a second skin. We deserve a country where fear is not the engine that keeps the system running, where safety is not promised to some by threatening others, and where power is not sustained by keeping people afraid.

Lima Halima-Khalil, Ph.D., is the program director of the “I Stand With You” campaign at ArtLords, a collective she co-founded, where she mobilizes global awareness against gender apartheid in Afghanistan. Her research explores youth resilience amid violence and displacement. Her writing has appeared in Foreign Policy, TRT World, and academic publications.

Chrissy Teigen: "This is what care looks like"

Against a landscape of shrinking reproductive freedom, the TV personality and author visits a Tennessee clinic that offers both birth and abortion care

Tomorrow marks the 53rd anniversary of the Roe v. Wade decision. More than half a century later, in a country that no longer grants the freedom that that ruling declared, it’s easy to get mired in the onslaught of harrowing news about our bodies and our lives. But everywhere, there are warriors who keep doing the work of caring for pregnant people, and they are not mired. They are moving forward, every single day.

TV personality and best-selling cookbook author Chrissy Teigen has herself helped to humanize reproductive healthcare. She has spoken about her own experience having a lifesaving late-term abortion; visited the Feminist Center for Reproductive Liberation, a clinic in Georgia, in 2024; and then discussed her experiences with Vice President Kamala Harris during the 2024 presidential campaign. “I started crying once I saw this beautiful mural of butterflies above the operating suite” at the Feminist Center, Teigen told Harris at the time. A doctor there “looked me in the eye and she said, ‘You could have had butterflies.’”

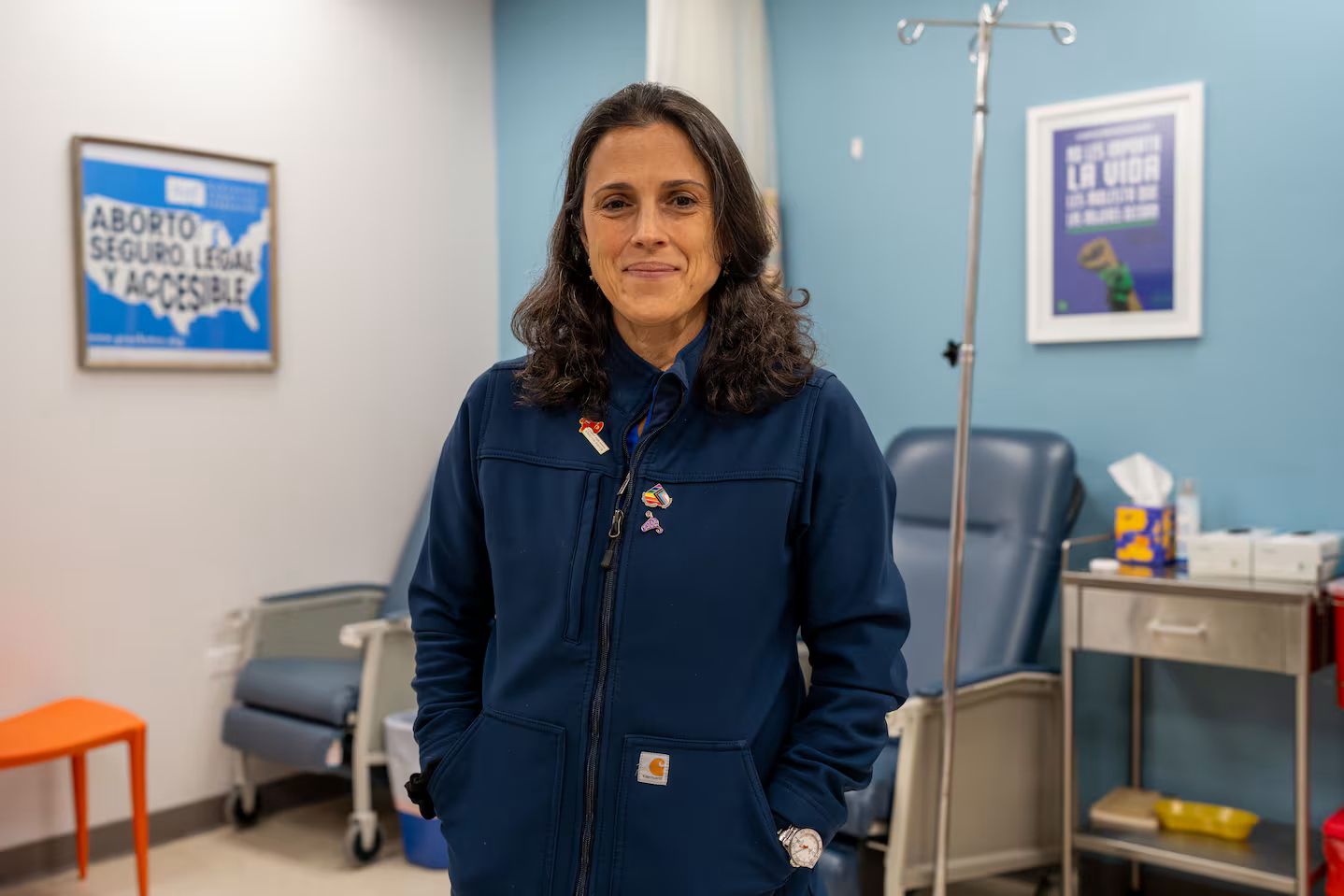

Then, in 2025, The Meteor traveled to Tennessee with Teigen on another visit—one that shows that everyone deserves butterflies, and that you can’t talk about abortion care without talking about maternal care. CHOICES Center for Reproductive Health, a Memphis-based clinic, provides the full spectrum of care for people who can get pregnant. “All pregnancies are different,” says Jennifer Pepper, CEO and president of CHOICES. That’s why the center provides everything from midwife-assisted births to high-risk pregnancy care to prenatal classes—and, since abortion was banned in the state in 2022, abortions in their sister location three hours away in Carbondale, Illinois. (Pepper says CHOICES is the only nonprofit in the country where both birth and abortion take place. And after Dobbs, “we could not stomach the idea that [abortion] patients wouldn’t have anywhere to go,” she says.)

“Every single woman deserves that level of care in America,” Teigen says. “This is what care looks like—people listening to you, and treating your body and your choices with dignity.”

Teigen was moved by how the clinic felt so “open and welcoming and airy and light,” with a “sisterhood” that was far from “the coldness” of her own hospital experience. “It never crossed my mind that I could give birth on all fours, or be in a tub at a birthing center,” she said. She saw a better way to give abortion care, too. When Pepper told Teigen she got her start at CHOICES as an abortion doula, Teigen said, “I can’t tell you how much I would have appreciated an abortion doula,” someone to explain “what was happening with my body.”

Tennessee also has the highest rate of maternal mortality in the country—and so access to supportive birth care can mean the difference between life and death, particularly for Black women. One Black woman in the prenatal class, Jasmine, recalled a conversation with her doula at CHOICES that started with a heartbreaking wish—“First off, I don’t want to die”—and ended with her having a “beautiful experience” delivering her baby.

“Every single woman deserves that level of care in America,” Teigen says. “This is what care looks like—people listening to you, and treating your body and your choices with dignity.”

Producer/director/editor: Emily Murnane

Producer: Rachel Lieberman

Director of photography: Mary Gunning

Audio: Stacia Gulley

Production assistant: Dindie Donelson

Production assistant: Nola Madison

Post producer: Annie Venezia

Graphics: Bianca Alvarez

Produced with support from Pop Culture Collaborative, as part of the United States of Abortion series.

Syria's Mothers are Fighting to Rebuild Their Homes

One year after the end of a long war, they tell journalist Tara Kangarlou what coming home has really been like

By Tara Kangarlou

“There are very few mothers here who haven’t lost a child or a spouse, and very few children who haven’t lost a mother or a wife,” says 62-year-old Khadijah as she sits on the floor of a heavily bombed building—flattened, except for the one room where she now lives with her 75-year-old husband, Khaled. Like most of her neighbors, Khadijah, her husband, and her children—previously displaced across Syria and neighboring Lebanon and Turkey—are now returning to their devastated hometown of Zabadani, wondering how to pick up fragments of a life uprooted.

The nearly 13-year-long war in Syria is known as one of the worst humanitarian crises of the 21st century. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the conflict displaced more than 13 million Syrians, including the six million people who fled to neighboring countries. For years, the war functionally dismantled the country’s healthcare and infrastructure and robbed an entire generation of school-aged children of their childhood and education—losses that ripple through every fabric of Syrian society today. The UN Human Rights Office has documented over 300,000 civilian deaths, with some estimates approaching half a million. Multiple mass graves have been found across the country, and Bashar al-Assad’s deployment of chemical weapons in Ghouta and Duma against his own people marked the deadliest use of such agents in decades.

This month marks a year since the fall of Bashar al-Assad, and over that time, millions of Syrians have been adjusting to their newly liberated reality. More than four million have made their way back to their villages across Syria—their homes reshaped by years of siege, bombardment, and civil war. In Zabadani, Eastern Ghouta, Madaya, Duma, and other hard-hit regions across the country, mothers—like Khadijah—are navigating these losses firsthand as they work to restore a semblance of stability for their families.

It should be a time of celebration, but for those living among the remnants of destruction, grief is pervasive. “Before the war, I would always wear white, but ever since the first death in our family, I’ve not taken off my black scarf,” Khadijah says. “I continue to be in mourning,”

Like so many others in Syria’s Zabadani region, Khadijah and her family hail from generations of experienced, hard-working farmers. But the land, once celebrated for its apple orchards, vineyards, and lush farmland that helped feed Damascus, endured one of Syria’s longest and most punishing sieges. Between 2015 and 2017, barrel bombs, airstrikes, and artillery shells rained down, destroying irrigation systems, flattening farmland, and contaminating the earth with heavy metals, TNT, and fuel residues. The blockade also choked off agricultural inputs—seeds, fertilizers, and clean water, leading to the collapse of a once-thriving rural economy.

“We’d feed an entire town with our fruits and vegetables, but now, we barely have enough to feed our own family,” says Khadijah, whose grievances are evident when you visit her farm, where the soil is depleted and infrastructure destroyed.

“The only people whose farmland was spared were the people who cooperated with the Assad regime,” Khadijah explains. “We’re grateful to be alive, and we will rebuild, even though right now, we just don’t know how.” Later, she recalls the harrowing days in 2015 when she, her two daughters, and her then two-year-old grandson, Ammar, were displaced to nearby Madaya as the Assad army besieged Zabadani. Soon, those under siege in Madaya were facing severe food shortages and starvation under a blockade imposed by Assad’s forces and his allies Russia and Iran-backed Hezbollah.

“Ammar’s father [my son-in-law] was just killed…when we were forcefully moved to Madaya,” she says. “We had so much grief. “For the nearly two years that followed, we had nothing to survive on except rationed sugar, bread, and at times animal feed and grass.”

It wasn’t until 2017, following months of siege, that Khadijah and her family were relocated to opposition-held Idlib where they continued to live in displacement with little means to support the family.

Now 22, Ammar is studying to be a medical technician in Idlib—a city that remained the only lifeline for hundreds of thousands of displaced Syrians during the war. Visiting his grandparents in Zabadani, he brings in freshly made Arabic coffee and sits next to his grandmother and 37-year-old uncle Omar, who lost an eye in the war. Both men look at Khadijah with deep respect and endearment. “Every single mother in Syria has suffered tremendously, including my own mother and my grandmother; but we are of this land, and we’re happy to be back,” said Ammar.

The Flowers Still Bloom

Across Syria, the devastating impact of warfare is as environmental as it is emotional.

Just an hour’s drive from Damascus, 35-year-old Hiba walks through her hometown of Duma in Eastern Ghouta, stopping at a perfume shop to buy rose-scented oils—a defiant joy after surviving years of siege, bombardment, and chemical attacks. “Everything above ground was destroyed,” she says, recalling giving birth during the war in a half-collapsed clinic with no medicine, water, or electricity. Today, Hiba calls her 7-year-old daughter, Sally, her best friend and the person who makes life meaningful. “She loves riding her scooter and wants to be a pharmacist,” Hiba shares.

During the war, inspired by her family’s struggles caring for her younger brother with Down syndrome, Hiba began working with children with special needs—a profession she continues to this day, despite her own personal battles.

“People were disconnected from the world,” she says, pointing to what once was her house—a collapsed building lying under the weight of repeated barrel bombs and artillery strikes. “Our country is destroyed, but we mustn’t forget what happened to us. Our children must remember everything—so it doesn’t happen again.”

Both Zabadani and the Eastern Ghouta regions stand as stark evidence of how siege warfare and chemical weapons became tools of collective punishment—obliterating not just lives, but the ecosystems and livelihoods that sustained millions of ordinary civilians, including mothers, who are now searching for hope amidst rubble.

Back in Zabadani, 35-year-old Lana—a mother of two toddler boys—walks the grounds of her grandfather’s house and what was once her safe haven as a child.. She is a psychologist who has recently returned to her flattened town after years of life as a refugee in Lebanon. Today, along with her husband, she’s back “home,” doing what she once dreamed of doing for her own people and community.

“This is my grandfather’s home. My daddy grew up here,” she says. “We used to play here as children.”

The building’s walls are pocked with shrapnel holes and its ceilings blown down into rubble, but as we climb up and walk into the remnants of the house, she suddenly turns around, tearing up. On a half-collapsed wall, a faint drawing survives—painted decades ago by Lana’s father as a child, and depicting a red house surrounded by trees and a bright blue lake—the last fragile trace of a family’s life before war.

“My daddy was an artist. I have to tell him this is still here.” She looks at the flowers growing from underneath a pile of stones and smiles: “See, even in the middle of this destruction, we still have flowers bloom. There is hope, Tara. We are here.”

Tara Kangarlou is an award-winning Iranian-American global affairs journalist who has produced, written, and reported for NBC-LA, CNN, CNN International, and Al Jazeera America. She is the author of The Heartbeat of Iran, an Adjunct Professor at Georgetown University, and founder of the NGO Art of Hope.

"We're Being Robbed of Time"

Two women share what it was like to lose their husbands to "self-deportation."

By Anna Lekas Miller

Ordinarily, Julie is a night owl. She is used to staying up late while her husband, Neftali, whom she affectionately calls “Nef,” goes to bed early to wake up for his construction jobs.

Even these days, “I find myself tiptoeing around at night, trying to be quiet,” she says. “Then I realize he isn’t there.”

Neftali didn’t pass away—in October, he made the difficult decision to “self-deport” to Mexico, leaving Julie, a U.S. citizen and business owner, behind in Newark, New Jersey. And like a growing number of families in Trump’s America, they are now living separated by a border, wondering what they have to do to find their way back to each other.

Julie, now 47, and Neftali, 45, first met through friends in 2008 and started dating in 2011. Back then, she didn’t think it was a big deal that he didn’t have papers. But when Trump first came to office in January 2017, they started getting nervous. The two went to City Hall to tie the knot, just to be safe. “We didn’t want to take any chances,” she says.

But when they went to adjust Neftali’s status, they were slapped with a rude awakening. Even as a U.S. citizen, Julie couldn’t sponsor Neftali—long before they met, he had crossed the border twice, and because of a piece of Clinton-era legislation, this meant that he was ineligible for a green card. At the time, they decided to do what they always do—look over their shoulder and stay away from police. But as Trump’s second crackdown on undocumented immigrants began, and they started to hear more stories of people being detained and even disappearing, Julie and Neftali began to reconsider their lives in the United States.

When the couple finally decided it was time for Neftali to leave the U.S. last month, Julie traveled with him. “I spent five days with him in Mexico, and it was one of the most painful, but exhilarating experiences.” Julie says. The moment there was no longer a threat of Neftali being arrested, she adds, both of them felt immense relief.

It is difficult to know precisely how many people have self-deported from the United States. The Department of Homeland Security claims that 1.6 million individuals have done so using the CBP Home app, but this number has been disputed.

Julie and Neftali represent one of 4.5 million “mixed-status” households across the country. Some of these households include a U.S. citizen married to someone without papers; others include children born in the United States to undocumented parents. All undocumented individuals are vulnerable now, but statistically, it is men who are more frequently targeted during ICE raids; when they are forcibly removed from their families, be it through arrest or self-deportation, their spouses and children are left behind to navigate a cruel system.

“We’re being robbed of time together,” Julie tells me. “When I’m having a bad day or a bad moment, I can’t feel him close like I do when he’s here.”

“We weren’t really living.”

Several states over, in North Carolina, Jenni Rivera, 54, and her husband, Fidel, 48, share a similar story. Jenni is a high school math teacher; Fidel, an electrician. They have two children together and met salsa dancing almost twenty years ago. “It was like the beginning of any relationship—we just couldn’t get enough of each other,” Jenni recalls.

Even though Fidel had been living in the U.S. without papers when they met, Jenni assumed that she could fix it through marriage. But when they went to an attorney, they learned that he would likely be barred from re-entering the country for 10 years if he tried to adjust his status. “At the time, we had an infant,” she tells me. “There was no way that I was going to separate my spouse from his daughter for 10 years.” So Jenni and Fidel accepted that they would continue to live in the shadows.

“We didn’t go anywhere [that] we couldn’t drive [to],” she remembers—boarding a plane and having IDs scrutinized by TSA agents felt too risky. That meant no more trips to Florida to see her family, and no vacations that weren’t within a short drive of their home in North Carolina. In the summer of 2024, Jenni took their daughters—both U.S. citizens by birth—on a road trip across the country, but without Fidel, it felt empty. “I knew he would love the prairie dogs,” she laughs, recalling a stop in South Dakota. “He would be making up stories about them, having ridiculous conversations with them, telling the girls stories from when he used to be a rancher.”

Over the years, it felt like the box they lived in was getting smaller and smaller. Even though they had all of the hallmarks of a good life—stable jobs, a nice house, two wonderful children—the constant threat of deportation made her painfully aware of the fact that she could someday be on her own.

“I could feel the walls closing in on us,” she describes. “We were living, but we weren’t really living.” Still, a lawyer had told Jenni that if Fidel ever got arrested, she could bail him out, and they would eventually have their day in court, where an “extreme hardship” provision in immigration policy might allow Fidel to stay in the United States. That gave her hope, but then, in September of this year, the Board of Immigration Appeals took this option away. “They blocked the one chance I had to fix anything.”

As time wore on, too, things got scarier. Detention centers, like Alligator Alcatraz, started popping up, and Jenni realized that Fidel might not just get deported—he could be detained for months, or disappear entirely. “My husband is such a good human. I did not want him to be in any of these places that we were hearing about,” she says. “I couldn’t live with myself. I wouldn’t be able to face my kids again.”

So, on October 10th, they celebrated their 17th wedding anniversary. They carved pumpkins and ordered pizza with their girls. Then Jenni helped Fidel pack for his flight to Mexico.

“It was really sad at the airport,” she tells me. “But I’ve been staying busy. I think it’s really going to hit in the quiet moments.”

"Our plans look a little different..."

One of many frustrations that Jenni and Julie share is the amount of apathy towards immigrants that they witness among other Americans. “It isn’t just about deportation anymore,” Julie says. “It’s about detention and people disappearing and making money on detained bodies. I’m disappointed more people aren’t outraged.”

“They are destroying families,” Jenni adds. “I can’t understand what these people did that was so bad that you would want to rip the foundation of their life apart.”

Since Fidel left for Mexico, Jenni has been focusing on helping her oldest daughter with college applications. “I know if they want to come to me, they’ll come to me,” she tells me when I ask how they’re doing. “I don’t want to burden them.”

Meanwhile, Julie is continuing to support other mixed-status families through American Families United, an organization that advocates for legislation like the Dignity Act, which would allow undocumented immigrants to regularize their status provided they pass a criminal background check and pay any taxes that they owe. She’s also looking forward to the next time that she can visit Neftali in Mexico—and hopes to eventually move there.

“We talk every night,” she says. Sometimes, they reminisce about the past; mostly, they look forward to the future. While they once thought this would be in the United States, now they know that this will be in Mexico.

“Our plans look a little bit different than how we thought they would look,” Julie says. There are logistical issues. Neftali had been paying for his niece’s education, which is going to be more difficult when he’s earning in pesos instead of dollars. Julie is working on finding a way to pivot her business to something that she can do from Mexico.

“I don’t want any more time to be stolen from us,” she adds. “We’re going to work as hard as we can, so we can have a beautiful future like we always planned.”

“I feel a sense of freedom,” she says. “It’s just not in the United States.”

Anna Lekas Miller is a writer and journalist who covers stories of the ways that conflict and migration shape the lives of people around the world. She is the author of the book Love Across Borders and runs a newsletter by the same name. Follow her on Instagram: @annalekasmiller.

"A revolution has begun. There is no going back."

On the anniversary of the Beijing women’s conference, a blueprint for a brighter future

Thirty years ago this month, women from around the world gathered for a conference that made history and, as it turned out, would not happen again. The 1995 UN Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing was a monumental moment for activists and world leaders who came together to “answer the call of billions of women who have lived, and of billions of women who will live,” as the first female Prime Minister of Norway, Gro Harlem Brundtland, put it at the time. It’s the meeting at which then-First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, building on years of women’s organizing, famously said, “Women’s rights are human rights,” which made global news because it was (and apparently remains) a radical perspective.

The journey to the conference—which is documented in a new multimedia project from the United Nations Foundation and co-produced by The Meteor—was two decades long, with previous meetings held in Mexico City, Copenhagen, and Nairobi. Beijing itself was the largest women’s rights gathering at that point in history, with a massive audience of 45,000 people invested in building a better future. Pulling it off was no small task, but the leaders charged with doing so were more than up to it. Among them was the inimitable Gertrude Mongella of Tanzania, the Secretary-General of the conference, who later became known as Mama Beijing. “A revolution has begun,” she said during a closing speech at the Conference, “there is no going back.”

Mongella was a key player in producing the Beijing conference’s most significant document: The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action—which remains the most comprehensive blueprint for gender equality and women’s rights ever created. It wasn’t just a wish list; 189 countries committed to it in Beijing. It demanded women’s inclusion in government and policymaking; economic policies built with gender in mind; the understanding that violence against women is a human rights violation; and was also one of the first international agreements to demand that governments complete a thorough analysis of how climate change and industrialization had affected women. From the Platform: “The continuing environmental degradation that affects all human lives has often a more direct impact on women…Those most affected are rural and Indigenous women, whose livelihood and daily subsistence depends directly on sustainable ecosystems.”

You probably know how this ends: While some of the Platform’s key goals have been achieved—women’s representation in government, for instance, has risen—many have yet to be fulfilled, 30 years later, not because of an absence of activism, but because of global backlash and competing priorities. But the women at the forefront of global change remain motivated. When asked what the next global feminist conference should focus on, Nyasha Musandu of the Alliance for Feminist Movements put it this way: “We must dare to dream bigger, disrupt deeper, and build bridges across movements. The fight for justice is not just about breaking barriers—it’s about reimagining the world itself.”

"Life Is Still an Open Wound"

Four years after the Taliban seized her country, Lima Halima-Khalil, Ph.D., reflects on the losses, joys, and complexity of life for young Afghans.

On August 15, 2021, time did not just stop; it dissolved. One moment, I was at my desk in Virginia, an Afghan researcher piecing together the life stories of Afghan youth for my doctoral research; the next, I was holding my breath between phone calls I could not miss. My computer screen became my only window to my country slipping away: convoys of cars carrying loved ones I could only follow on Google Maps, the low, frantic hum of evacuation messages on What’s App, and the heavy silence between each update.

That day marked the beginning of the final withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan, following a deal signed with the Taliban that effectively handed the country over to them. The elected president fled, and fear settled like smoke across the nation. Thousands rushed to the airport in blind panic, terrified of what the return of Taliban rule would mean. Many of the young people I had interviewed joined the crowds at the gates along with their families (and mine too), desperate for a flight to anywhere. Between August 15 and the final U.S. military departure on the night of August 30, over 200 people died at or near the airport: some trampled in stampedes, some shot, some who fell from planes, and 182 of them killed in a suicide bombing on August 26.

It is hard to explain how, in an instant, everything that anchors your life, your home, family, career, the freedoms you’ve built over a lifetime, can be stripped away. You are left with two choices: walk through the valley of death into a new world naked without any resources, or stay in darkness, losing every human freedom and shred of dignity under the Taliban barbarism. Every year on this day, I try to tell my story and the stories of hundreds of my countrymen and women. I have never quite managed to capture the full weight of what we lived through, or what we are still enduring. But I know who I am: I am Lima Halima-Khalil, and I know that if we do not tell these stories, we risk losing more than a country; we risk losing the truth of who we were and who we still are.

Watching my country disappear

That day, as haunting footage of young men clinging to U.S. military planes, their bodies falling through the sky, was shown over and over on TV, my inbox was flooded in real time:

“Lima, they’ve reached the city gates.”

“My office is closed, they told us not to come.”

“Can you help me get my sister out?”

I typed until my fingers ached—evacuation forms, frantic emails, open tabs of flight lists—while my mind kept circling back to my sister Natasha. She was 24 when the Taliban killed her with an IED in 2020 on her way to work. Every young woman who called me that August day and over the last four years sounded like her: “Please, Lima, don’t leave me here. Save me.” Somewhere in that blur of urgency and grief, I knew I was watching my country disappear in real time.

The words of one young woman—an accomplished artist—still echo: “I wasn’t mourning just a country. I was mourning the version of myself that could only exist in that Afghanistan.”

In the months and years that followed, I carried my interviewees’ stories inside me. I felt the humiliation of the young woman who had to pretend to be the wife of a stranger just to cross a border. I felt the fear of the female journalist who hid in the bathroom each time the Taliban raided her office. I felt the silent cry of the father who arrived in a foreign land with his toddler son and wife and wandered the streets in winter, looking for shelter. I had nightmares over a young man’s account of seven months in a Taliban prison, tortured for the “crime” of encouraging villagers to send girls to school.

Four years later, August 15 is still an open wound. Afghanistan is now the only country in the world where girls are banned from secondary school and university. Women are barred from most jobs, from traveling alone, from their own public spaces. Half the nation is imprisoned; the rest live under constant surveillance.

Believe in change

However, the past four years have not been made up of grief alone. Even in exile, even under occupation, life has found a way in. I have witnessed many Afghan women earning their master’s degrees in exile. I have seen my young participants inside the country opening secret schools for Afghan girls in their homes and enrolling in online degree courses, while those in exile run online book clubs and classes for girls, refusing to let hope die. I have seen families reunited after being separated for four years. I see Afghan identity and tradition celebrated more than ever.

In my own life, some moments reminded me why I still fight: celebrating the birth of my daughter, Hasti; dancing with friends after completing 140 hours of interviews for my PhD; standing on international stages to speak against gender apartheid, carrying my participants’ words across borders; watching my research shape conversations that challenge the erasure of my people.

Like the two sides of yin and yang, these years have been both destructive and generative. One hopeless day, I called a participant still in Jalalabad. Halfway through, I asked, “What is giving you hope today?” She didn’t pause: “The belief in change. I don’t believe things will remain like this, where women are not allowed to live with full potential in our country. I will not stop my part, which is to keep studying and to believe that I will be the first female president of Afghanistan.”

Hope resides in me, too. This year, on this painful anniversary, I ask the world: the war that began in 2001 was never Afghanistan’s war, and today, it is still not the burden of Afghan women and girls to carry alone. So please, don’t turn your face away. Do not accept the narrative that this is simply Afghan tradition, that women are meant to live like this. That lie has been fed to you for too long. The women and girls of Afghanistan are humans. Until we see them and treat them that way, this gender apartheid will not end.

Lima Halima-Khalil, Ph.D., is the program director of the “I Stand With You” campaign at ArtLords, a collective she co-founded, where she mobilizes global awareness against gender apartheid in Afghanistan. Her research explores youth resilience amid violence and displacement. Her writing has appeared in Foreign Policy, TRT World, and academic publications.

They Were Told “Don’t Write, Don’t Post, Don’t Report”

For Iran’s fearless women journalists, every byline is a form of rebellion

By Tara Kangarlou

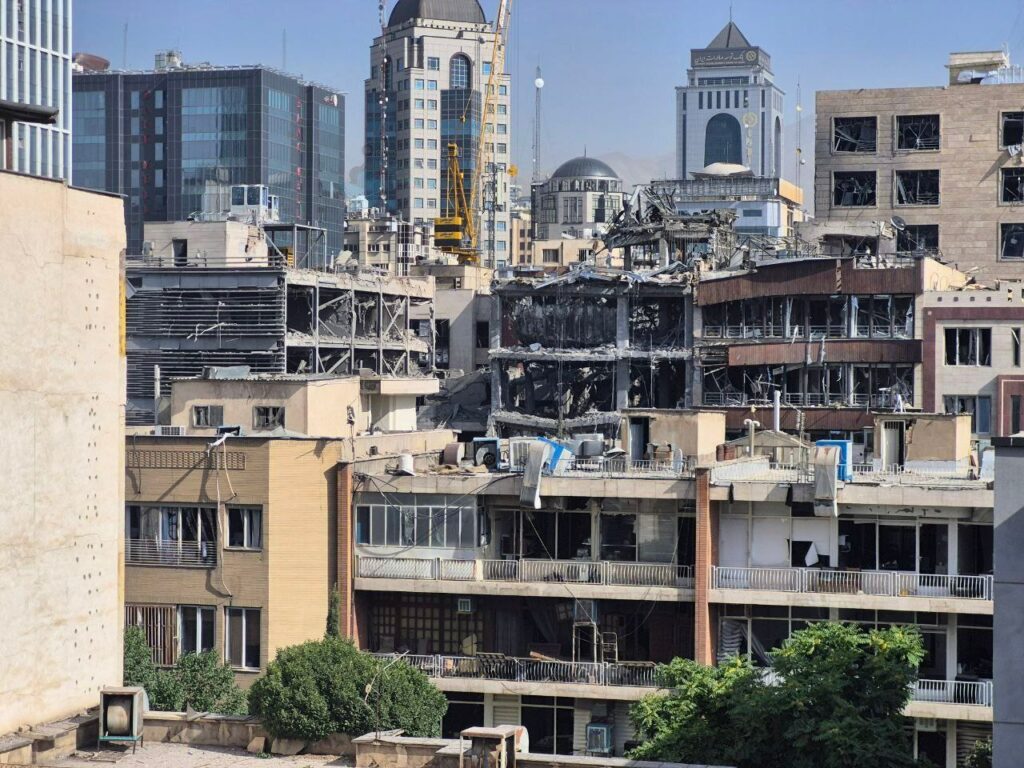

“To be a war correspondent is like a wounded dove flying through a pitch-black tunnel. It crashes into the walls over and over, but keeps going, for a chance to send the message, to save others,” says Arameh, a 40-year-old Iranian journalist. She and her two colleagues, Samira, 39, and Parvaneh, 27 (all have been given pseudonyms for their safety), are among the many brave Iranian journalists who remained on the ground in Tehran to report on the 12-day Israel-Iran war earlier this summer.

The women work for one of Iran’s prominent news sites, covering social, local, and political issues. Although the outlet is independently owned, it still falls under the heavy scrutiny of the Islamic regime’s watchful eyes. (Out of the utmost caution, we’ve withheld the name of the website.) “Despite slow internet and censorship, we wrote, posted, and published” throughout the war, recalls Arameh. “With images of blood and death flooding in, we kept reporting.”

Ultimately, Iran’s missile attacks on Israel killed 28 people and wounded more than 3,000, some of them civilians. Israeli airstrikes on Iran killed more than 1,190 people and injured 4,475, according to the human rights group HRANA. As in many conflicts, Western coverage of the war zeroed in on geopolitics: the Islamic Republic’s hardline rhetoric, the regime’s nuclear ambitions, and the fate of a theocracy teetering on the edge. Yet beneath those soundbites, a generation of fearless, tenacious young journalists—many of them women—tirelessly documented life under foreign bombardment and domestic censorship in the world’s third-largest jailer of journalists.

According to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), more than 860 journalists have been arrested, interrogated, or executed in Iran since the 1979 revolution, which brought the Islamic Republic to power. RSF also reports that since Mahsa Amini’s killing in September 2022, at least 79 journalists, including 31 women, have been detained—with some still behind bars. The International Federation of Journalists and Iran’s own Union of Journalists report even higher figures, estimating that over 100 journalists have been detained during this period, most in Tehran’s notorious Evin Prison. Among those held were 38-year-old Elaheh Mohammadi, her twin sister Elnaz, and Niloofar Hamedi, who first broke the news of Mahsa Amini’s killing for Shargh Daily in September 2022.

My connection to these women goes beyond our shared profession—I was born and raised in Iran and immersed in all the complexities of its everyday life; but today, as an American journalist with dual nationality, I can no longer return freely to my country of birth—simply because my profession is deemed threatening to the forces at home. I often have nightmares of being arrested in Iran or of never again seeing my childhood home; but what gives me hope is the strength of women like Arameh, Parvaneh, and Samira, who stayed. They do so knowing their government is always watching, listening, and ready to punish them for telling the truth.

These women were not just covering a war; they were surviving it.

On the war’s second night, 27-year-old Parvaneh tried sleeping in the newsroom as her home was in an evacuation zone. It was just her and the office janitor, whose pregnant wife and daughter had already left the city after their neighborhood was hit. That night, Parveneh recalled, “the sirens were so loud that neither one of us could sleep, so I stayed up all night and covered the strikes.”

On day three, Arameh convinced her aging parents, brother, sister, and five-year-old niece to leave Tehran without her. “With each strike, I’d tell my niece it was a celebration or fireworks,” she recalls, heartbroken that the little girl believed her each time.

Similar to many other journalists and photographers in the country, Arameh and her colleagues received anonymous calls from intelligence agents and government officials warning, “Don’t write. Don’t post. Don’t report.” But as always, they did. Samira reassured her mother, whose brother was killed in the Iran/Iraq war in the 1980s, that she would not leave Tehran. “I’m a journalist,” she explains. “If I’m not here in these days, it would be like a soldier abandoning the battlefield.”

“We adapted; we always do,” Arameh says. “We stopped giving exact locations or numbers. Instead, we reported where sirens were heard. We told people how to protect their children. In times of war, a journalist must also be a source of empathy.”

For journalists in Iran, adaptability is a necessary skill as they navigate censorship, surveillance, and threats from a regime that has long waged war on its own press. These women documented both the human devastation of the war—including the Tajrish Square bombing that left 50 dead—but also the ongoing intimidation from the state toward members of the press. That intimidation extends to those who defend journalists as well. Human rights lawyers such as Nasrin Sotoudeh, Taher Naghavi, and Mohammad Najafi have been imprisoned for the “crime” of representing journalists and activists.

“My beautiful Tehran felt like a woman who had been brutally violated; battered, broken, bleeding,” says Samira, recalling the last night of the war. “It was the worst bombardment; something inside us died, even as the ceasefire began.”

On June 23, just one day before the ceasefire that would end the war, Israeli airstrikes hit Evin, killing at least 71 people—among them civilians, a five-year-old child, and political prisoners, including journalists. Nearly 100 transgender inmates are presumed dead—all people who should never have been there from the start.

The world often celebrates Iranian women in hashtags and headlines, but falls silent when it comes to tangible support. Heads of state, renowned public figures, and human rights organizations call for freedom and justice, but political inaction persists.

“If such strikes happened elsewhere—especially Europe or the U.S.—the world would’ve cried out,” Arameh says. “But in Iran, the Iranian people are always defenseless. People around the world talk about loving Iranians, but…we are once again left alone in our pain.”

Iranian journalists are not asking to be saved. They are asking to be heard, to be respected as the only eyes and ears of millions whose voices have been stolen by a regime that does not represent them. More than anything, these independent journalists, who are not funded by the regime and continue to report under severe censorship and surveillance, are emblematic of a deeper reality: that Iranians—especially women, and especially young people—stand firm in their pursuit of truth, change, and growth, no matter the cost.

Tara Kangarlou is an award-winning Iranian-American global affairs journalist who has produced, written and reported for NBC-LA, CNN, CNN International, and Al Jazeera America. She is the author of The Heartbeat of Iran, an Adjunct Professor at Georgetown University and founder of the NGO Art of Hope.

The Call Is Coming From Inside the Villa

Love Island: USA has Latine viewers confronting their anti-Black history

By Julianne Escobedo Shepherd

Love Island is the escapist watch of the summer with its outsized personalities and tropical setting—but as the aftermath of this season has proven, it’s never truly an escape from the dynamics of the real world.

A little background if you’re not one of the tens (hundreds?) of millions that made this season Peacock’s biggest streaming series ever: Love Island is a reality show in which a dozen “sexy singles” are sequestered inside a neon villa with the sole directive to find love amongst themselves, has been airing for a decade in the UK, and six years in the U.S., but it didn’t really take off here until last year, thanks to improved production values after a switch from CBS to Peacock. This summer, it was an inescapable hit: Love Island seemed like the only thing unifying the country, to be honest, a fact I chalked up to our desperate collective need for an hour of reprieve from encroaching fascism. And since it airs almost every single day for two months, it’s easy to immerse oneself in the petty dramas and flirtations of its sculpted and spray-tanned twenty-something cast.

I’ve been watching Love Island for years—last summer I realized I had seen over 550 episodes, at which point I had to stop counting—and like the best reality shows, it manages to put larger-world concerns under a microscope; its anthropological utility is vast. Even in its unreal Fijian (or Mallorcan) setting, familiar biases and prejudices play out in real time. And this year especially, anti-Black racism has shown up both in the villa and among the show’s fanbase.

This year was notable for the way Olandria Carthen and Chelley Bissainthe, this season’s beloved Black women leads, were characterized by fans and certain tabloid media. They were both perfectly dignified and two of the main reasons the season was watchable—only to find that, having emerged from the villa at the end of the season, they’d been saddled with the “angry Black women” stereotype. (Production has also been accused of airing decontextualized outbursts by Huda Mustafa, Love Island’s first-ever Palestinian cast member and an outspoken mother, while editing out the male behavior that led to her outbursts.)

Further, two contestants, Yulissa Escobar and Cierra Ortega, were unceremoniously disappeared from the villa after old social media posts surfaced in which each used racist terms—the n-word and an anti-Asian slur, respectively. And last week, it emerged that previous contestants JaNa Craig and Kenny Rodriguez had broken up after a year—allegedly due to his racism against JaNa. (I’m using first names here since that’s the way viewers know the cast.) A post by friend and castmate Leah Kateb charged Kenny with being a “racist, clout/money hungry and a scammer,” while JaNa’s best friend, Charmane Smith, doubled down on the accusations, implying that Kenny had been texting friends about how he does not like Black women. Kenny has not yet responded to these specific allegations, but in aggregate, the headline-making racial dynamics that have surfaced are appalling.

And it was even more disconcerting that the three contestants accused of bias are all Latines of various origin, with a white Cuban from Miami (Yulissa), a Puerto Rican/Mexican Angeleno (Cierra), and a non-Black Dominican from Dallas (Kenny) at their center. As De Los’s Alex Zaragoza pointed out after Cierra’s ouster, “anti-Blackness and white supremacy is sadly part of the fabric of our culture across Latino communities in all parts of the U.S.”

Colorism and racism have long been a massive problem among our U.S. Latine communities, and in Latin America, too; it’s a pervasive issue that dates back to both the enslavement and genocide of Africans and the 15th-century Spanish invention of las Castas—the racial caste system put into place as the conquistadors colonized Indigenous lands. The idea that lighter-skinned people deserved higher social and economic standing was crucial for Spaniards in maintaining control, and it embedded itself into cultures across Latin America, with flare-ups along the way.

For instance, in the mid-century Dominican Republic, the dictator Rafael Trujillo used anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism to foment division and entrench his fascist rule (sound familiar?), a legacy that reverberates today. And for too long, mainstream media in Latin America has spread the message that white is more right, whether in the faces that populate our novelas or those that deliver our newscasts. (Recall, for instance, the racism faced by the Mixtec and Triqui actor Yalitza Aripicio, after her Oscar nomination for the 2019 film Roma.) In the U.S., white assimilation demands that Latines shed our identities, which is how you get brown Latines going full stan for Trump, even as his administration kidnaps and sends our families to concentration camps.

Fortunately, young people seem much more inclined to call out and combat anti-Black racism, and racism in general, among Latines. They know that Latines’ fraught experience with colonialism doesn’t excuse us from the task of trying to eradicate this problem within our communities and our families; that if we are to be united towards liberation, eliminating anti-Blackness from within is an essential first step. And if it takes Love Island, a reality show defined by thong bikinis and nasty-looking egg breakfasts, to spark this conversation, then I suppose we can call it a net good. Even if you inadvertently lose half your summer watching it.

The Year of "Mar-a-Lago Face"

It’s time to talk about the campy aesthetic of Trumpworld women.

By Nona Willis Aronowitz

What, exactly, is the “MAGA look”? Like pornography, you know it when you see it: It’s an exaggerated performance of traditional gender norms so common among the women of Trumpworld that it’s known as “Mar-a-Lago face.” It may involve Botox, cheek implants, fake eyelashes, injected lips, glossy waves, and a surfeit of bronzer. Think of the over-the-top looks sported by DHS Secretary Kristi Noem, strategist Kimberly Guilfoyle, and former RNC chair Lara Trump (as well as a few rightwing men, like Florida congressman Matt Gaetz).

What does this increasingly ubiquitous look tell the world about gender and power? What do these women gain from transforming themselves? And is it even worth talking about, given the recent onslaught of horrors? I called writer Inae Oh–who consulted historians, sociologists, and plastic surgeons for the best piece I’ve read on the subject, a Mother Jones feature–to ask about the deeper meaning of the trend.

Nona Willis Aronowitz: Before we get into it, what would you say to those who think focusing on people's (and mostly women's) looks is besides the point—that we should solely focus on their terrible actions? Are we just using the same weapons against them that people have always used against women?

Inae Oh: I would say, “I hear you!” But I would also argue that it is a mistake to dismiss the issue as superficial–the aesthetics of fascism have long been preoccupied with restoring gender norms and ideas of perceived "perfection," something we clearly see playing out both in the aesthetics and politics of MAGA.

Believing that this is besides the point also risks misunderstanding the forces that animate Donald Trump: appearance over substance, one's TV performance over policy, propaganda vs. reality. These are some of the most powerful people in the United States, imposing some of the most consequential policies in decades. Their deliberate choices are worthy of interrogation.

Kristi Noem has been such a central figure in the last couple of months. What does her visual presence signal to you?

Her aesthetic choices dovetail very nicely with the administration’s promise to take mass deportations to an unprecedented level. This is a priority for them, and the face of that priority really matters to Trump. I think there’s a reason why it’s not Stephen Miller out there. Trump has explicitly stated to Noem, “I want your face in the ads.” She’s gone through a dramatic transformation from when she was South Dakota's governor to what she looks like now.

Basically, she’s a woman with a look that’s very rooted in conservative, traditional ideas of what a woman should look like: long, flowing hair, heavy makeup, form-fitting dresses–but at the same time she has that baseball cap on and she’s employing incredibly harsh and cruel and aggressive policy. That supposed contradiction is intentional. Her look also provides cover for the brutal policies that are being implemented across the country. [After Sen. Alex Padilla was forcibly removed from a press conference], Rep. Anna Paulina Luna (R-Fla.) defended Noem and described her as “the most delicate, beautiful, tiny woman.” She said, “What actual testosterone dude goes in and tries to break Kristi Noem?” All of a sudden, she’s a defenseless woman.

There are certainly some precedents to the MAGA look in conservative politics and media; Fox News hosts of the last couple of decades come to mind. What’s different now?

I mean, it’s Donald Trump. It’s turbo-charged now. This is a man who literally has a background in reality TV. This is a man who doesn’t really know policy, who only cares about how you appear and how you can sell a certain idea. And [Trump’s taste is] extremely garish. Trump is notorious for his love of gold. It can seem so tacky to me, personally, but to him, it signifies wealth and power. When you have the most powerful man in the world having those priorities, people use these visual signifiers to gain power and favor.

Is this really just a rightwing thing? Lots of people, particularly women, feel pressure to conform to a certain look, which increasingly includes cosmetic enhancements.

I’m also a woman in this world, and I absolutely partake in our capitalist beauty standards. Plenty of people on the left, people who are my friends, are also opting to undergo procedures like Botox. You have Gen Z on TikTok being very open about the work they’ve done on their faces. For the longest time, plastic surgery was not accessible to the masses…As it has gotten cheaper and more normalized, people have become more open about it, like how Kris Jenner documented her facelift.

So it’s not completely divided by politics, but I think what’s happening on the right is a bit different. It’s such an appeal to tradition, whereas on the left, there’s more of an embrace, politically and culturally, of gender fluidity. And there’s more of an embrace of sustainability with companies like Reformation and green-friendly makeup, whereas on the right, that’s not at all a concern; it’s all about excess.

Men are secondary to this phenomenon, but they’re certainly in the mix. How do you think the MAGA aesthetic plays out when it comes to masculinity?

Pete Hegseth, to me, is the male equivalent of Kristi Noem. Men like him wear these bright-colored blue suits that don’t just fade into the background, and are supposed to be a sign of patriotism. Their shoulders are extremely broad, whether that is natural or not. Their chins, their jaws are very chiseled. It’s such an aggressive, cartoonish way to represent gender norms, and that absolutely plays into this Donald Trumpian idea of a powerful man. It’s not as ridiculous as the women, maybe because they don’t wear as much makeup. Do these rightwing men want to be known for caring about their looks? Absolutely not. They would see that as a sign of weakness. But there have been reports of Hegseth installing a makeup room in the Pentagon. [“Totally fake story,” Hegseth responded on X.] He puts that same importance on visuals and the message, rather than budgets and policies.

The Evolution of the Rightwing Lewk

Conservative politics has always demanded that women perfectly embody the gender norms of the era.

1970s: Phyllis Schlafly

The “godmother of the conservative movement” intentionally wore ultra-feminine outfits–preppy pastels, skirts in the pantsuit era, and pussy bows–while attacking the Equal Rights Amendment.

Early ‘00s: Gretchen Carlson

Famously crowned Miss America in 1989, she was one of many prominent “Fox blondes.” (In a twist, she was later key to taking down Fox News CEO Roger Ailes for sexual harassment.)

2008: Sarah Palin

Known for her sexy soccer mom look (with a rifle!), she ushered in a departure from the gender-neutral appearance of most female politicians at the time.

2025: Kristi Noem

Tasked with carrying out some of Trump’s cruelest policies, she is the platonic ideal of Mar-a-Lago face: pillowy lips, blinding white teeth, long wavy hair, and lots of makeup.

Is the Last Abortion Haven in the Caribbean Closing?

How U.S. influence has been quietly reshaping access in Puerto Rico

By Susanne Ramirez de Arellano

Dr. Yari Vale's petite frame is no longer weighed down by the nine-pound bulletproof vest she wore when anti-abortion threats increased after the end of Roe v. Wade, but she hasn't gotten rid of it. The security guard at Dr. Vale's Darlington Medical Associates clinic in Río Piedras is no longer at the door; still, she has him on standby. With the return of Donald Trump to the White House and Jenniffer González, a Trump devotee, in the governor’s seat, Dr. Vale is bracing for an escalation in the fight to safeguard reproductive rights in Puerto Rico.

The predominantly Catholic island is “on paper one of the most accessible places in the Western Hemisphere” to obtain an abortion, NPR reported just after Roe was overturned. But with the U.S.'s shift toward right-wing Christian nationalism, that could be changing.

Dr. Vale, an OB/GYN at the Darlington clinic—the only one of the island's four that does late-term abortions—is on the frontline of the fight to keep what’s happening in the United States from happening in Puerto Rico, euphemistically called an unincorporated territory (it's a colony, really). It's a battle that, she says, feels like “throwing a firecracker up in the air, and it's just smoke and no one hears you.” But she persists, knowing that the first line of defense is the clinics.

The Legacy of Pueblo v. Duarte

For years, Puerto Rico has been known for its liberal abortion laws: The right is enshrined in the island’s constitution (which exists separately from the U.S. Constitution) and is protected by the right to intimacy under Puerto Rico’s penal code. Abortion is legal on request if it is performed (or prescribed) by a physician to protect the pregnant woman’s life or health—and health includes mental health. There are no limits (abortion may not be banned before viability; post-viability abortions are permitted for the preservation of the pregnant person), and the procedure doesn't require the consent of partners, ex-partners, or, in the case of minors, parents.

However, these laws have their roots in a dark colonial history. In 1902, four years after invading the island, the U.S. enacted policies to control the population, although abortion was still prohibited without exception. Then, in 1937, colonialists who wanted to further limit the Puerto Rican population passed legislation based on racist neo-Malthusian and eugenic theories, virtually legalizing abortion on the island if it was to protect the life and health of the patient. These changes later facilitated clinical trials of the contraceptive pill and mass coerced sterilizations—a procedure that became so common that it was known among Puerto Rican women as “la operacion.”

In 1980, a case involving a minor and her doctor went even further, and set up modern abortion law in Puerto Rico. In the landmark Pueblo v. Duarte, Dr. Pablo Duarte Mendoza, who had performed an abortion on a 16-year-old girl in her first trimester, was sentenced to four years in prison. He appealed, and the Puerto Rican Supreme Court agreed with him, stating that through the island’s penal code, abortion is legal if it is performed to save the woman's life or health, including mental well-being.

Like many things on an island impacted by colonialism, abortion access is still limited for everyday Puerto Ricans. A surgical abortion costs $250, and a medication abortion between $300 and $350; meanwhile, about 43% of Puerto Ricans live below the poverty line, and insurance plans on the island do not cover abortion. And in addition to cost, religion and social stigma—the “what-will-my-family-say” factor—serve as deterrents for many women.

The Dobbs Effect

When 2022’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision removed the constitutional right to an abortion in the U.S., it didn’t automatically affect rights in Puerto Rico (unlike on the mainland, where “trigger bans” were in place). In fact, some U.S. women began to travel to Puerto Rico from states with restrictive abortion laws, such as Florida. It was the return of the “San Juan holiday.”

But Dobbs did embolden conservative Puerto Rican politicians and pro-life groups, who saw a window of opportunity and seized it. Shortly after the decision, the right-wing religious party Proyecto Dignidad (PD) adopted the U.S. anti-abortion lobby's blueprint and tried to push through several bills to curtail access to abortion, and even criminalize it. They argued that the end of Roe implicitly negated Pueblo v. Duarte. The Senate ultimately defeated the bills; according to many Puerto Rican legal experts, Pueblo v. Duarte rests on the Puerto Rican penal code, which has no analogy in the U.S. Constitution—and should, therefore, not be affected by Dobbs.

An Ascendant Right-Wing Movement

Abortion-rights advocates warn that efforts to criminalize abortion in Puerto Rico are not over. Traditionally, “the issue of abortion in Puerto Rico has not been the overriding controversy that the anti-abortion and ultra-religious politicians want to make it out to be now,” says Senator Maria de Lourdes Santiago, a lawyer and Senator for the Puerto Rican Independence Party (PIP). But, she says, the anti-abortion campaign orchestrated by Proyecto Dignidad now "magnifies the issue to demonize it."

Founded in 2019, PD has capitalized on its nexus of Catholic and Evangelical churches; the erosion of the traditional duopoly of the pro-statehood New Progressive Party (PNP) and the Popular Democratic Party (PPD); and an increasingly ultra-conservative sector of the population urging a return to traditional values. Even though the party got only seven percent of the vote in the 2024 elections, its influence is strong island-wide, with a campaign that now hinges on the abortion issue.

Proyecto Dignidad Senator Joan Rodriguez Veve, a canon lawyer and face of the populist religious right, has vowed to continue fighting to restrict access to abortion. She recently introduced legislation, PS 297, restricting access to abortion for adolescents under the age of 15. The bill is a carbon copy of one that the Puerto Rican House rejected a year ago. It calls for jail time for any doctor or person who assists a minor in getting an abortion, and a slew of other measures, including forensic interviews of minors seeking an abortion.

The Senate approved the bill in February, and almost everyone I spoke to—politicians, legal experts, and abortion doctors—told me they believe it will pass, even though both pro-abortion and some anti-abortion groups have, for different reasons, voiced their opposition to the measure.

A New Generation Stands Up

At the same time that PD is gaining influence, attitudes about abortion are shifting with the younger generation. Rising numbers of people support abortion rights, and young people have galvanized around the issue, taking to the streets in protest and amplifying groups like Aborto Libre Puerto Rico, Profamilias, and Proyecto Matria, among others. It’s a generation that, unlike its mainland counterpart, grew up without a sense of abortion as a wedge issue.

Most recently, health professionals and activists have spoken out against PS 297, warning that the bill puts women and girls in danger. “What's going to happen here is that young women and those most vulnerable will seek out illegal abortions and go to the places where illegal drugs are sold to purchase abortion pills, many cut with fentanyl, in doses that are not recommended,” says Puerto Rican feminist activist Alondra Hernández Quiñones.

As religious and conservative groups gain traction in Puerto Rico, Dr. Vale worries that a girl of 15, whose parents are ultra-conservative and refuse to consent to her abortion (as the new legislation would require), would be forced into motherhood. Clinics like Darlington have stopped seeing patients younger than 15 at all, and Dr. Vale fears a future where abortion, currently a safe and regulated procedure, “will once again be a public health problem…where we don't know how many women end up in emergency rooms due to an [unregulated] abortion gone wrong.”

“This worries me a lot,” says Isharedmie Vazquez, a 17-year-old Puerto Rican student. “It seems incredibly wild to me that instead of guaranteeing secure options [for an abortion], what they are looking for is to criminalize it and force women to assume a responsibility for which they are not prepared. It's unfair that they want to take away the right to decide about our lives.”

Susanne Ramírez de Arellano is an author on race and diversity, opinion writer, and cultural critic. The former news director of Univision, she writes for NBC News Think, Latino Rebels, and Nuestros Stories, among other outlets.

Susanne Ramírez de Arellano is an author on race and diversity, opinion writer, and cultural critic. The former news director of Univision, she writes for NBC News Think, Latino Rebels, and Nuestros Stories, among other outlets.