How to Fight Autocracy, From the Activists Who’ve Done It

BY MEGAN CARPENTIER

When Donald Trump vowed in December 2023 to be a dictator “on day one,” his aides later clarified that he “was simply trying to trigger the left and the media.” Nonetheless, exit polls showed that half of voters “said they were ‘very concerned’ that another Trump presidency would bring the U.S. closer to authoritarianism,” even though some voted for him anyway.

In the weeks since the election, democracy advocates have raised the alarm about the possibility that, after nearly 250 years, the American system of constitutional governance may be compromised. Many people are worried that Trump will try to hold onto office illegally in 2029; he’s told voters, special interest groups, and House Republicans he’s considering an unconstitutional third term. Critics note his hostility to the free press, his early demands that all his appointments skip confirmation hearings (to which Senate Republicans currently seem unlikely to acquiesce), and his promises to use the Department of Justice to go after perceived political enemies.

Looking at history, the worry that Trump could destroy some of the fundamental guarantees of democracy are not without precedent: All around the world, voters in democratic countries have elected leaders who then undermined the very systems that brought them into power—including the 20th century’s most infamous authoritarian, Adolf Hitler.

How does that happen? What lessons can—and should—Americans learn from other countries which have recent experience with authoritarian rule? Given that scholars have repeatedly found that authoritarian countries are worse for women’s equality, this guidance feels more needed than ever.

So we asked the advice of a few activists from across the globe who know what it’s like when authoritarianism comes your way.

“People exchange their freedoms without actually realizing the consequences for everybody.”

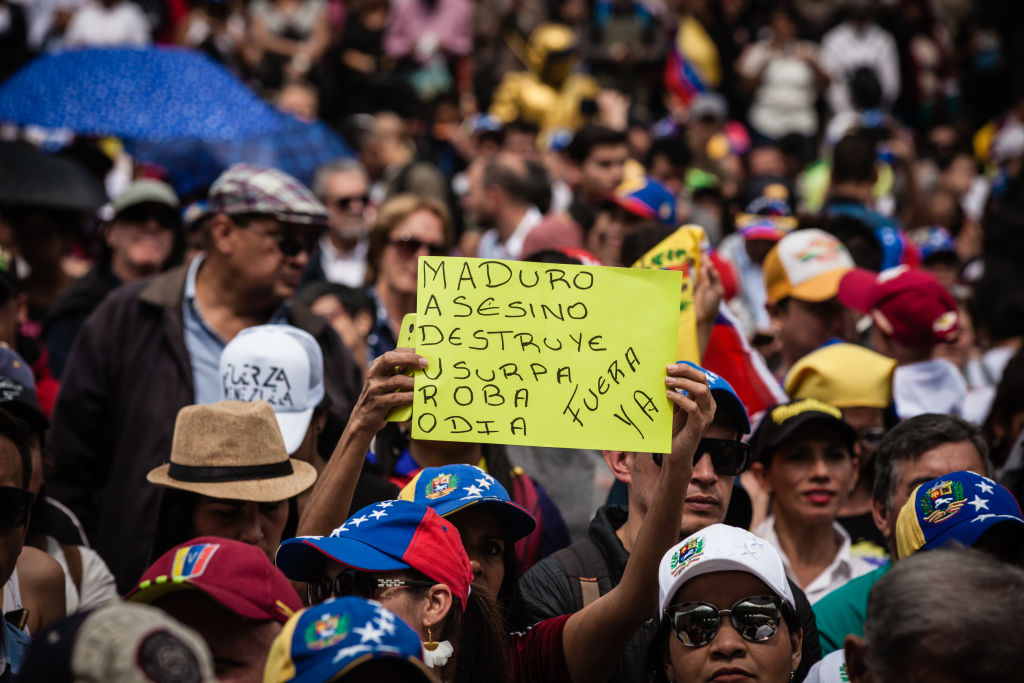

—Génesis Dávila, founder and president of Defiende Venezuela. In Venezuela, current president Nicolás Maduro—handpicked successor of autocrat Hugo Chávez—presides over an authoritarian regime, and recently declared victory in an election he is accused of rigging.

“Something that we couldn’t learn on time in Venezuela is that polarization is a poison for the entire society. When we had Chávez and then Maduro in power, they targeted the opposition as enemies and, when they did that, then the opposition also targeted them and their supporters as enemies. The opposition would say Chávez supporters were not smart people, that their values were against the country’s.

“It worked in favor of Chávez and Maduro. I would not want to support someone who is attacking me. I would not want to support someone who believes that I’m not smart. I would not want to support someone who thinks that my values are wrong and their values are right.

“Chávez came to power with the support of the people [but]…he took control of the judiciary and the legislative branch. He announced limitations on freedom of speech; he announced the reform of the Constitution. At the end, he was pretty much able to do whatever he wanted without any resistance. He had 100 percent impunity. [And under Chávez and then Maduro], we moved from being a strong democracy with a strong economy to one of the poorest countries in our region.

“We cannot perceive our fellow citizens as our enemies. We have different perspectives, different values, but we must be willing to find common ground. We need to create bridges, and we need to help them to walk to the other side—but we cannot push them, and we cannot attack them.”

“You can’t protect democracy if you’re not offering a really inclusive social and economic agenda.”

—Gábor Scheiring, Assistant Professor of Comparative Politics at Georgetown University in Qatar and a former member of the National Assembly in Hungary, where Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has ushered in what the European Parliament has denounced as an “electoral autocracy.”

“I’m a huge supporter of liberal democracy and institutions, but you can’t really protect those cherished liberal institutions by just talking about how important it is to have a constitutional court and how important media pluralism is. The overwhelming majority of people don’t really think in these terms. They are concerned about inflation and real wages and unemployment and inequality, and that’s where you need credibility if you’re trying to represent those masses.

“So, the old elitist ways of doing progressive politics will not help you. You can’t just continue talking about the values of democracy, as opposed to talking about issues that matter to people. That’s just not working. It’s not helpful.

“You need to convey a message of significant change, and do that in a credible way….Beyond that, in the U.S., if you have any friends who have a lot of money and can use it to support significant, large, liberally-oriented media outlets, I think that’s super important….If we’re frank, conservative billionaires, they invest in conservative media, even if it doesn’t pay out immediately. Liberal billionaires in Hungary, they just did not really care to help sustain non-right-wing media. And I think that’s a huge, huge problem.”

“As long as people remain organized, there is hope.”

—Halil Yenigun, Associate Director, Stanford University’s Sohaib and Sara Abbasii Program in Islamic Studies, and former professor in Turkey, where President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s time in office has generally been characterized as a movement away from democracy.

“There are a few basic differences between the Turkish government and the American one today that favor American democracy.

“One is that the U.S. judiciary is still a lot more independent than Turkey’s ever was. So even when Trump transgresses certain limits, some conservative justices still stand up against him, like they did with the election fraud claims. The second one is that the U.S. is a federal government, and federalism still creates some kind of counter-force to a centralized, authoritarian government. Don’t take the institutions for granted. Don’t take checks and balances for granted.

“Another institutional mechanism [in both the U.S. and Turkey] is the opposition party organization. Turkey had a multiparty democracy before President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was first elected, and, even after, the opposition party organizations did not give up….Each and every election, they just continued fighting back.

“Even though in Turkey, we did not have the same kind of strong civil society as in the U.S.—we don’t have as many NGOs—civil society proved to be a very important channel for people to remain organized. There are still these openings to express opposition to the regime, like Pride Day and especially the women’s movement and the annual Women’s March. [That] movement might seem as though it is about a single issue like women’s rights, but it serves as a channel for people to vent their resentment against repression.

“These pockets of resistance are very important, I think, to prove that people can still fight back.”

“We realized that we needed to inform people what human rights are.”

—Cristina Palabay, secretary general of the human-rights organization Karapatan in the Philippines, where former president Rodrigo Duterte’s term from 2016 to 2022 was characterized by extrajudicial killings, human rights abuses, efforts to change the country’s constitution, and more.

“How Duterte spoke about human rights was, ‘OK drug addicts are not humans, They are animals.’ This was the dehumanization in which the administration was engaging.

“We realized that we needed to go back to basics, to inform people what human rights are. We had to explain that human rights are more than what is written in the Constitution—more than just legal rights. Human rights are the right to a dignified life, the right to food, the right to just wages, the right to live at all. People can have a basic understanding of human rights when it is spoken about in a way that is easily understandable to them.

“But, as we were educating people, the situation kept getting worse. When kids started to get killed in the drug war, that’s when people started to think, OK, so, this is not just about drug addicts. And then, of course, he went after the human rights defenders and he took a militarist approach during the pandemic.

“Based on this education, people started to question the dehumanization of people. And that’s when we realized that Duterte’s propaganda was not as widespread a success.

“It became a defining moment for many of us—civil society, social movements, journalists, even artists—to all come together to mount some kind of pushback, including online. And we did that.”

Megan Carpentier is a freelance writer and editor. She is an alumna of NBC News, The Guardian, Talking Points Memo, and Jezebel, among others, and her byline has appeared in Foreign Policy, Ms. Magazine, Rolling Stone, Esquire, Glamour, and The New Republic.