“I’m Not Afraid to Keep Talking”

BY SAMHITA MUKHOPADHYAY

As I began reflecting on the five years since #MeToo went viral, I found myself thinking, maybe surprisingly, of the many years that came before it. I thought about the Take Back the Night marches I attended in college, the organizations that had long been committed to eradicating rape, such as RAINN or the New York and California Coalitions Against Sexual Assault, and anthologies like Yes Means Yes, edited by Jaclyn Friedman and Jessica Valenti in 2008 in which survivors shared their experiences and talked openly about rape culture. After all, Tarana Burke, the leader of the #MeToo movement, coined “me too” in 2006.

Today we celebrate the anniversary of a breaking point: the moment it went from a conversation in the margins to one that couldn’t be ignored. But survivors have been coming forward with their stories for a long time, and we wanted to take today to reflect on the work that came before 2017 and the work that lies ahead.

I knew exactly who I wanted to talk to in honor of today’s anniversary: my dear friend, feminist, anti-rape advocate, writer, Mornings with Zerlina on SiriusXM, and author of The End of White Politics, Zerlina Maxwell.

Samhita Mukhopadhyay: One of the first conversations we ever had with each other, over 10 years ago, was bonding over being survivors.

Zerlina Maxwell: I remember; it was in that bar in Brooklyn. We talked about how we both had issues sleeping after our assaults. And we cried and we held hands. I think it was like meeting a “friend soulmate” but also meeting someone with the same scars on our souls. It was a connection through a shared and deep pain.

By the end of the night, we were best friends. How did you first come forward with your story, and what was that experience like?

I hadn’t really called it anything yet…and when I explained what happened to someone the day after it happened, their answer back to me was: “That sounds like sexual assault.” So I went to the hospital to officially report it, and the police also responded to me: “What you describe is a sexual assault.” So for me, I think it was getting other people to say it to me. [That’s] when it became real. I knew something bad happened to me right away and was really numb but hearing people call it sexual assault helped me begin processing the trauma.

I think it happens differently for everyone. And sometimes it can take a really long time because you’ve tried to probably block it out and move on and pretend it didn’t happen at all, or maybe that it was just some confusing thing. And it’s the process of coming to terms with what happened: Something really did happen, and now my life would never be the same again. It was kind of world-shattering.

But I think what broke me more than the actual assault was the people who didn’t believe me. That’s what bothered me the most. Because I always felt like I’m a very trustworthy person. I really don’t lie. I just try to be honest about stuff, and for people to be like, “I don’t believe that happened to you,” that broke my spirit. I was lost for a few years and a shell of the person I was before or who I am today. The impact of the victim blaming is actually what broke me. I don’t think people really recognized how traumatizing that part of it could be. And I really broke. I fell all the way apart.

This was in the early 2010s, long before #MeToo. In 2014, there was a similar hashtag, #YesAllWomen, which women were using to share their experiences with sexual assault. How did that make you feel?

Validated. It made me feel less alone. That’s one of the reasons I wanted to talk about it: Because I knew it wasn’t just me.

One of the things I [realized] was this idea that we believe that good things happen to good people and bad things happen because you did something bad, or bad circumstances happen because of a mistake that you made and a choice that you made. But that is bullshit. And that was one of the big realizations I had, like, “Why is it that people are blaming me for what happened? Why?” I didn’t understand that. I was like, “I didn’t do anything. I didn’t make choices that led to that.”

And through that [questioning], I gained a level of courage. Because once I felt like I figured it out, I was like, “I found the matrix: [it was] rape culture.”

The right criticized #BelieveWomen as ignoring evidence and facts. We know that was a disingenuous argument because no one ever meant, “Believe all women no matter what the facts are.” What do you mean when you say it?

When I’m saying you’re believing somebody as a default position, what you’re defaulting to at that moment is empathy and compassion. I always tell kids on college campuses; if you don’t remember anything I said today about rape culture, I want you to remember one thing. And it’s that if somebody comes to you and they say, “I think,”—which is usually what they say, “I think I’ve been sexually assaulted,” and not, like, “I have been”—you say in response: “I am sorry. How can I help?” That’s all you’re going to say. You’re not going to say, “Are you sure?” You’re not going to say, “Oh, were you drinking?” You’re not going to say, “What were you wearing?” All of those things. You’re not going to say any of that. You’re just going to say, “I am sorry that happened to you. How can I help?” That’s all you’re going to say.

You don’t have to make a judgment call at that moment about a verdict or about the case. People get too caught up in that. Besides this idea that people have, “Well, I don’t want to believe without evidence,”—I always like to remind them that in the law, testimony is actually evidence. Sure, there are other types of evidence that you can use to corroborate, and certainly, physical evidence is helpful but not always present in cases like this. But testimonial evidence is evidence. And I want to live in a world where somebody’s account of what happened to them is taken seriously and not shot down.

In 2013 you were on Fox News. You made a statement and it turned into a… I mean, it was a zoo of getting attacked. So walk us through what you said on the air. What happened?

Fox called me to do a segment. The Colorado state legislature was debating a law that would legalize concealed carry on college campuses. And I was like, “That’s not a good idea.” And one of the people that testified was talking about how she was sexually assaulted on a campus in a place where there weren’t guns allowed. And if she had had her gun, she would’ve been able to defend herself. And so the premise of the segment on hand was, “What’s wrong with the people in Colorado? Why won’t they let women defend themselves with guns…that they can carry everywhere to prevent sexual assault?”

And my argument in the segment was, I don’t want or need a gun to not be raped. There’s nobody jumping out of the bushes. It’s the people that you know, your family members and your friends and your intimate partners, classmates, and your colleagues who [rape you]. And so I reframed it in the segment and I said, “Don’t tell me I need a gun. Tell men not to rape.”

And after the segment, I got death threats and rape threats.

People were like, “What do you mean, teach men not to rape??” And I was like, you have to start teaching people about consensual sex, affirmative consent. And men are not being taught that. They’re being taught that women are literally objects that they’re supposed to dominate. And if they can liquor them up to make it easier, then that’s what they are encouraged to do through popular culture. And that’s resulting in real-world harm. And I just wanted to reframe the conversation away from the things that women are always told they need to do to prevent their own assault. I hate that shit.

What was going through your mind five years ago when #MeToo broke through and people started to pay attention?

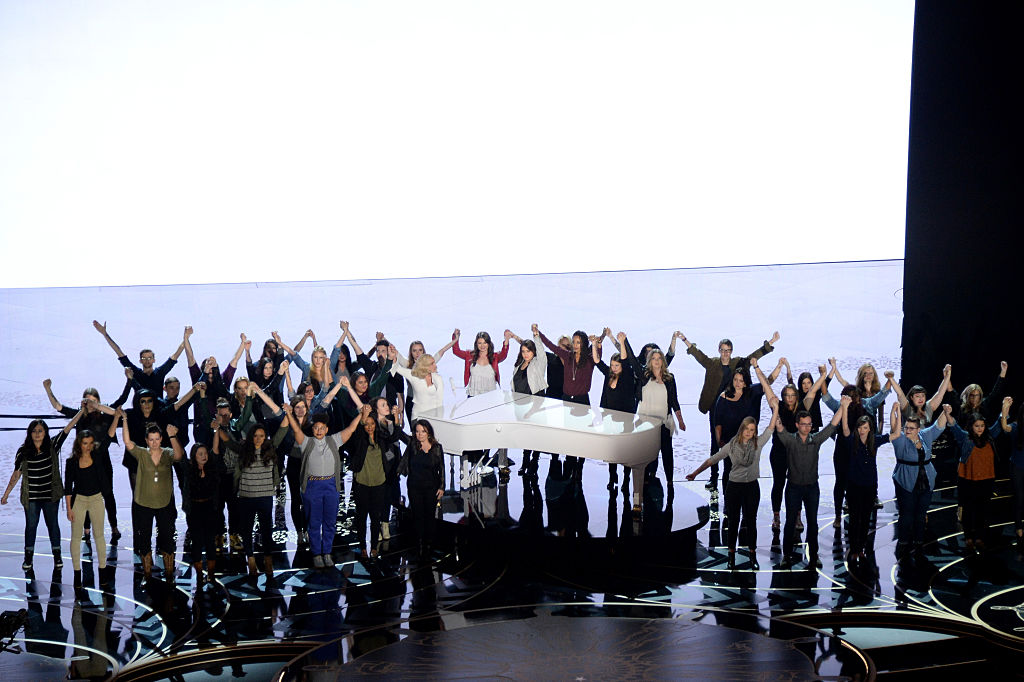

One of the things that happened before that story about Harvey Weinstein came out in 2017 is that at the beginning of 2016, I went to the Oscars. I went to the Academy Awards with Lady Gaga and 50 survivors. It was a life-changing experience. It was a diverse group of people in all aspects—on the gender binary, racial, age, everything. She was performing Till It Happens To You because it was nominated for Song of the Year, and we were invited to stand in solidarity with survivors, triumphant and speaking about our experiences. It was an emotional experience. There was a lot of crying. People were triggered. Lady Gaga was triggered. She walked [into rehearsal one day] and just burst into tears. And she was talking about how seeing us she felt a validation that she kind of had never felt before.

So when Harvey Weinstein’s story broke, and all these famous women started coming out, I thought back to the Oscars because that was before that; I mean, he was still having his big party the year that we did our performance. He was still Harvey Weinstein then. But obviously, there was a dam that was about to break because those emotions were really raw that night.

And I think there’s a momentum that comes with seeing somebody else come forward… Number one, you realize you weren’t the only one that had that story—but also that you’re more likely to [be] believe[d].

So how are you feeling now, five years since #MeToo went viral, and 10 years since you started talking about sexual assault publicly? And do you think that we’re kind of in the midst of a backlash in some ways?

Oh yeah, we’re definitely in the midst. And can we just be honest about the fact that there’s a spectrum? Everybody that is on the survivor side of this conversation is acknowledging that not everybody’s assault is the same. And somebody that is touching you inappropriately, or putting their hand around your waist, like Al Franken, is not the same as Bill Cosby or Harvey Weinstein. We all understand that. Everybody understands that. You’re acting dense and gaslighting us to believe that we’re the ones that are overreacting.

When you think about what just happened with Johnny Depp and Amber Heard, the backlash is pretty clear at this point. I mean, I think unfortunately, we overcorrected back to worse than even we were before—maybe in terms of not just believing the woman, but literally destroying her if she had the nerve to talk about something that happened to her. And if, God forbid, she’s not the perfect victim, then we’ll destroy her. We won’t only not believe her, we will destroy her.

Do you feel any hope for the future?

I think that Gen Z certainly is empowered to talk about assault. And I’m not afraid. I’m not afraid to keep talking even though there is a backlash. Because any backlash or hate comment you can send to me that’s not going to be worse than the actual assault that I have survived.

Samhita Mukhopadhyay is a writer, editor, and speaker. She is the former Executive Editor of Teen Vogue and is the co-editor of Nasty Women: Feminism, Resistance and Revolution in Trump’s America and the author of Outdated: Why Dating is Ruining Your Love Life, and the forthcoming book, The Myth of Making It.