She Fled Fear—and Found It Here

A woman who escaped danger in Afghanistan reflects on what life is like under ICE.

By Lima Halima-Khalil

I drop my three-year-old daughter off at library classes every morning. The library is two minutes from our home in Ashburn, Virginia. Each time, the same thought crosses my mind: Do I have my ID on me? Will my driver’s license be enough if I am stopped?

It is highly unlikely that I will encounter ICE on a two-minute drive to the library. Ashburn isn’t exactly an ICE hub. And yet my fear is constant, embodied, and real. And by the way, I am an American citizen.

I grew up believing America was a mighty country, one so powerful that the rest of the world stood intimidated by its strength. When I first came to the United States in 2006 for an education program from Afghanistan, a country still at war, the vastness of this place revealed itself not only in its size, but in the generosity of the people I met. After that, America became a place I always returned to. I have been part of the American education system since 2010, returning several times for various degrees. I’ve witnessed multiple presidential elections and participated in the most recent one as an American citizen myself.

But after all these years, one lesson about my new home stands out above the rest: This country is led, shaped, and sustained by fear. Outside this country, nations tremble at the military and economic power of the United States, but inside it, people live as though danger is always lurking.

Fear raises money and sustains campaigns. Fear keeps people glued to screens and locked into cycles of outrage. Fear sells guns, justifies surveillance, expands borders and prisons. Much of this fear is not grounded in lived reality but manufactured and amplified by politicians who rely on it to govern. Fear spills into kitchens, sidewalks, classrooms, and moments meant to be ordinary and human.

One of the most brutal tools in this ecosystem right now is ICE. Raids, detentions, and aggressive enforcement practices operate not simply as immigration policy, but as a mechanism of fear, reminding entire communities that their sense of belonging is fragile and conditional. ICE does not need to be everywhere to be effective. The possibility of its presence is enough.

This pervasive fear turns ordinary routines into sites of anxiety. I remember hesitating before offering to share our Thanksgiving meal with our nosy white neighbor, suddenly gripped by thoughts I never imagined I would carry. What if he calls the police on us and claims I was trying to poison him? What if kindness itself is misread as a threat, or hospitality as danger?

Afghans discovered how quickly they could become the “other,” regardless of their sacrifices, their loyalty, and their love for this country.

I recognize these impulses, because fear is not new to me. I lost my school, my home, my loved ones, and eventually my country because I wanted freedom from fear. Millions of Afghans had believed in democracy when America promised it to us for 20 years, until the United States withdrew from Afghanistan in 2021. We voted, we hoped, we worked alongside our American partners for a shared dream, but that freedom never came. In 2020, when my 24-year-old sister was killed by the Taliban in an IED attack in her car, that truth became undeniable. I understood then that Afghanistan was no longer safe, and that realization is what led me to come to the United States permanently.

When the Taliban returned to power in 2021, many Afghans, including members of my own family, were evacuated and brought into this country by our American allies. They arrived in this country under extremely harsh circumstances, believing they would find dignity, safety, and a chance to contribute. Instead, they discovered how quickly they could become the “other,” regardless of their sacrifices, their loyalty, and their love for this country.

I was reminded of this again in November of last year, after a man from Afghanistan, who had been trained and worked for the CIA in his country, shot two National Guard members in Washington, D.C. Overnight, an entire community began to be seen, once again, as terrorists. Instead of a careful and humane conversation about mental health, trauma, or resettlement failures, the Trump administration halted all immigration from Afghanistan and pledged to re-examine green card holders from 19 countries. Afghans, many of whom fled the very forces America claims to oppose, were once again forced to prove their innocence.

This is how fear functions. It identifies a moment of tragedy, strips it of context, assigns collective guilt, and converts pain into political currency.

For a long time, I believed that fear in this country belonged primarily to people of color, that violence was uneven, predictable, and racialized. Then the killings of Renée Good and later Alex Pretti shattered that belief. They forced a painful realization that in today’s America, no one is safe, not five-year-old Liam Conejo Ramos, not women citizens like Dulce Consuelo Díaz Morales and Nasra Ahmed, not elderly citizens like Scott Thao or longtime residents like Harjit Kaur, not white Americans, either.

Lately, I have felt fear settle into my own body in a way I did not expect. I realized I had been going to sleep holding fear, living with the same quiet dread that so many people here carry without ever naming it. One night, I caught myself thinking, almost with disbelief: Congratulations, Lima, you are an American now.

But it does not have to be this way. Americans deserve more than this constant weight of dread, clinging to them like a second skin. We deserve a country where fear is not the engine that keeps the system running, where safety is not promised to some by threatening others, and where power is not sustained by keeping people afraid.

Lima Halima-Khalil, Ph.D., is the program director of the “I Stand With You” campaign at ArtLords, a collective she co-founded, where she mobilizes global awareness against gender apartheid in Afghanistan. Her research explores youth resilience amid violence and displacement. Her writing has appeared in Foreign Policy, TRT World, and academic publications.

Courage and cigarettes

Women Around the World

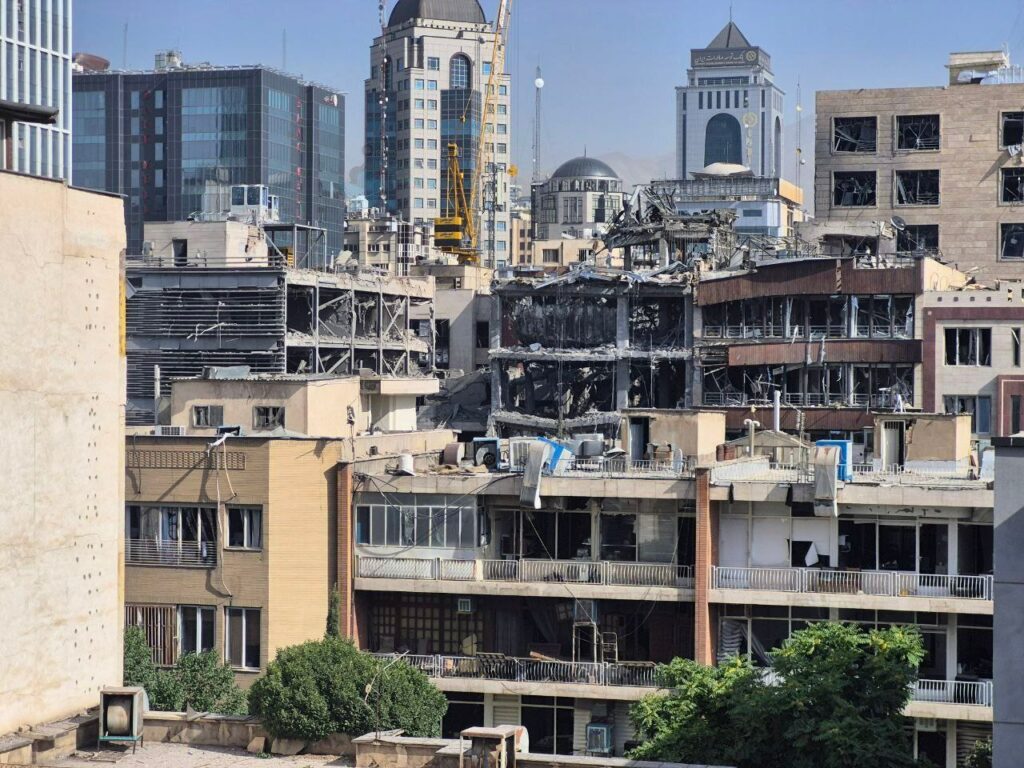

January 15, 2026 Greetings, Meteor readers, My kid is getting her tonsils taken out this week. Any parents out there with tips on how to survive the recovery period, I welcome the guidance. On to bigger things. In today’s newsletter, protests in Iran have already reached a terrifying death count. Plus, the government is investigating Renee Nicole Good’s widow instead of focusing on her killer. Popsicles for the apocalypse, Shannon Melero  WHAT’S GOING ONA history of resilience: At the end of December, shopkeepers and business owners in Tehran shut down their stores and took to the streets in protest. Within hours, a chant at the heart of the protest had spread across the city: “Our money is worth less.” What began as a localized economic complaint has grown into a nationwide anti-government protest that has reportedly claimed the lives of thousands of Iranians. To outside observers—especially those of us caught up in our own country’s headlines—this was a startling escalation. But for those living and working in Tehran, the writing was on the wall for some time. The Iranian economy has been in crisis mode for months: sanctions from the U.S., a 12-day war with Israel, water shortages, and in December—apparently the last straw—Iran’s currency, the rial, hit an all-time low. In an initial response to the protests, the Iranian government offered a monthly stipend to alleviate financial woes that was equivalent to seven U.S. dollars. It was an insulting band-aid. And as protests continue, Iran’s leaders have resorted to suppression and violence, attempting to keep Iranians quiet with internet blackouts, imprisonment, and murder by officials of the regime. And while all Iranians are suffering as a result of economic and political instability, this is yet another situation in which women will suffer the most. A UN Women report from 2024 found that Iranian women are more than twice as likely to be unemployed as men. In times of political upheaval, those numbers—along with sexual and physical violence against women—are expected to worsen. We have all seen this before. Time after time, the Iranian people have risen up against their leaders despite being met with the cruelest response. In 2022, after the killing of Mahsa Amini, which sparked the Woman, Life, Freedom movement. In 2021, over water shortages. In 2019, over fuel prices. In 2009, over questionable election results. But some Iranians who spoke to the New York Times said that these protests felt more powerful than even those of 2022 because they have captured Iranians from all walks of life. Young women have been front and center; the internet is full of images of Iranian women using burning pictures of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to light their cigarettes. Conservative and rural Iranians—who for the most part remained on the sidelines during the Women, Life, Freedom movement—are making themselves heard now. “We can see from the news and from some government reactions that this regime is terrified to its bones,” one protester in Tehran told a Times reporter. Many in the streets, on the other hand, are projecting fearlessness. “We are not afraid,” said Sarira Karimi, a University of Tehran student who was arrested last month, “because we are together.” The Trump administration has been keeping an eye on the situation, and earlier today, the president suggested that he was open to an airstrike, writing on Truth Social that the U.S. was “locked and loaded” and that “help was on the way” for protesters (excuse us?). He added that the military was reviewing “some very strong options.” No mention yet if Trump intends to be the acting president of both Venezuela and Iran, but it wouldn’t surprise anyone. AND:

PROTESTORS IN MINNEAPOLIS THE DAY AFTER GOOD’S MURDER (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

OF COURSE THE GAY SHEEP ARE SERVING LOOKS TO THE CAMERA (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Tears, Joy, and Fear

January 7, 2026 Salutations, Meteor readers, Happy New Year, friends, it’s good to see you all again. We hope you had a lovely stretch of time off from the real world and are ready to jump back into the massive amounts of everything going on. In today’s newsletter, one of our colleagues shares a personal reflection on what this past week has been like as a Venezuelan living in the United States. Plus, we mourn the loss of a maternal health advocate. Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON

I'm Anti-Trump and Venezuelan. This Week Has Been ComplicatedMy heart is celebrating while my brain sees the bigger picture. MADURO AND HIS WIFE ON THEIR WAY TO A FEDERAL COURTHOUSE IN NEW YORK. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) On January 3rd, the U.S. seized Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife in a military operation that shocked the world. The reaction from many Americans, who have lived through this playbook before, was outrage. The arrest of Maduro and his arraignment in New York courts has been perceived as an attempted regime change, a violation of international law, and an oil grab—all of which, to be clear, it is. (And there’s probably more madness ahead, given Trump’s comments about how “we need Greenland.”) So what does it all feel like for Venezuelans? After Trump declared that he plans to “run” Venezuela, many are fearing for their safety. At the same time, some Venezuelans in the United States are celebrating the removal of an oppressive dictator from power. For our colleague Bianca—a progressive Venezuelan living in the U.S., who asked that we withhold her last name due to privacy concerns—the moment was quite complex. Here’s what the last few days have been like for her. I'm 100 percent Venezuelan, born in Caracas. I grew up going to El Ávila National Park and the beaches of Margarita Island and just enjoying my country. But when [former president] Hugo Chavez got into power in 1998, the whole country was sort of panicking because of the authoritarian policies. Protests started. Repression and political polarization got gradually worse. Friends and family were put in jail simply for expressing their views. By 2007 or so, media suppression intensified; If The Meteor were in Venezuela, everybody [working here] would be in jail. I was part of the first wave of Venezuelans who left, although much of my family stayed. When I got to Miami in 2001, when I was 21, I totally disconnected from my Venezuelan life. For a decade, I just felt like “I don’t want to deal with this”—kind of what people are doing now in the U.S. It was too much and too painful. Then the 2014 protests happened [sparked by an attempted rape of a student in San Cristobal]. The government was killing students in the streets. That’s when I decided to go to Venezuela with my camera, so I could document the reality of what was happening. Public opinion in the U.S. seemed to frame the student protesters as privileged Republicans. When I started interviewing these students, I discovered that was not true. I met kids from the slums of Venezuela, 15 or 16 years old, narrating their torture incidents in prison. I realized it wasn't a left versus right thing–it was a human rights thing. VENEZUELANS OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED NATIONS OFFICE IN CARACAS DURING THE 2014 PROTESTS. (PHOTO BY BIANCA) These kids were just begging the UN to come help, and they never did. After that, I came back to the U.S. and dedicated myself to social justice. I am a Democrat who is against authoritarian regimes, unfair elections, media censorship, and political repression. I've lost [Venezuelan] friends and family because I was a Bernie supporter, and they cannot believe how I can support Bernie as a socialist [because Chavez and his successor Nicolás Maduro were socialist]. Which was why it felt weird to see Trump’s tweet about how Maduro had been captured. Trump’s tweets usually have a horrible, disgusting effect on my heart, but this is the one time a Trump tweet made me incredibly happy. I woke up my mom and gave her the biggest hug and we both started crying. It finally felt like a little bit of justice. I can see why other left-leaning people in the U.S. are scared that this is going to become another Iraq–especially coming from Trump. I saw what happened with Afghanistan and Iraq, and I was against all of it. But I am disappointed to see my flag being used to push agendas; I’ve seen non-Venezuelan protesters [in the U.S.] with Venezuelan flags holding signs saying “Free Maduro.” And we have been screaming for help for years. Some of the arguments [point out that] this violates international law. Okay, but where was the international law when we were asking the UN to come, or when [Maduro] stole the election from us last year, or when they were massacring kids? Where was the international law when we were asking for so much? BIANCA IN 2014 WITH A PROTESTOR WHO WAS IMPRISONED UNDER THE MADURO REGIME. (PHOTO BY BIANCA) We are in a moment where we have to learn how to hold two opposing truths at once. My heart is celebrating while my brain is carefully thinking through the bigger picture. We deserve this joy after so many years. But there is much more to do to re-establish democracy in my country, and I’d be shocked if Trump were the person to do it. —as told to Nona Willis Aronowitz  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

A "Magical Moment" for Abortion Access

December 18, 2025 Howdy, Meteor readers, After spending portions of this week kneading pizza dough, baking a bajillion cookies, and hand-churning vanilla ice cream—I will NEVER joke about being a one-woman bakeshop again. I’m leaving this to the professionals.  MY VERY PROFESSIONAL BAKING ASSISTANT KNEADING BAGEL DOUGH. AND YES THAT IS A BABY APRON. In today’s newsletter, we hear from the Slovenian activist who helped make history for abortion access in Europe. Plus, Scarlett Harris on the anniversary of that cinematic masterpiece: 9 to 5. Hanging up the apron, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONA million voices strong: Yesterday, the European Parliament approved a citizens’ initiative (ECI) that will improve access to abortion care for women across Europe. The initiative, led by a group called My Voice, My Choice, calls for the European Union to fund abortions in any participating member state, even if the person seeking care is from a country with an abortion ban. That means that a pregnant woman in anti-abortion Poland could have a safe, legal procedure in Slovenia–and the EU would foot the bill. This unexpected victory is three full years in the making. “Everyone said it was impossible,” My Voice, My Choice founder Nika Kovač tells The Meteor. The current parliament, consisting of representatives from the member states of the European Union, was extra-conservative, and the group needed to collect one million signatures in a year for the ECI to be brought to the floor.  NOVAČ AND HER COLLEAGUES SHORTLY AFTER THE DECISION ON WEDNESDAY. (PHOTO BY ČRT PIKSI) People told Kovač she’d never get a million signatures. They were right: She didn’t get a million; she got more, 1.12 million. It was the fastest-growing ECI in history. But why would a woman from Slovenia, where abortion is a protected right, take up such a long-shot cause? “I was living in the United States when Roe v. Wade was overturned,” she says. “To me, it was so shocking that the rights of people could go backwards. That’s why I became obsessed with the idea that we need to do something in Europe so it wouldn’t happen to us.” Kovač spent several years collaborating with advocacy groups across Europe to bring this initiative to a vote, a “big-tent coalition” that, in addition to women’s organizations, also included men, religious people, and conservatives. Still, as recently as this week, she expected to lose. “At the debate [the day before the vote], the opponents seemed very organized,” she says. “But when the vote came in, it was one of the most beautiful feelings in the world. They tried to convince us for so long that reproductive rights was a divisive topic. This was a magical moment of maybe there is some hope in a time of darkness.”  SOME OF THE MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT WHO VOTED ON THE INITIATIVE. (PHOTO BY ČRT PIKSI) The hard work doesn’t stop there. The specifics of the funding and how exactly countries that opt in can receive it now rest in the hands of the European Commission, which has one year to set out any measures it deems necessary. My Voice, My Choice will be part of that fight, as well. But before all that, “we’ve decided to take a break for two weeks,” Kovač says. “Sometimes, the most revolutionary thing you can do is rest.” AND:

9 to 5 Showed the Struggles of Women in the Workplace. If Only It Felt More Dated!Happy 45th birthday to a classic.BY SCARLETT HARRIS  THE HOLY TRINITY. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) In our post-girlboss landscape—where so much pop culture, from the truly terrible All’s Fair to next year’s The Devil Wears Prada 2, is set in the workplace—it may be hard to imagine, but when 9 to 5 hit theaters 45 years ago this month, people were hungry for media portrayals of working women. There were 25 million women in the workforce by then, one in three of whom were employed in clerical positions like those depicted in 9 to 5, but they didn’t show up much onscreen. 9 to 5 changed that The 1980 film, which still feels modern and vital, follows three women working at the Consolidated Companies: supervisor Violet Newstead (Lily Tomlin), a widow who is angling for a promotion to support her four kids; Doralee Rhodes (Dolly Parton), the beleaguered assistant to nightmare boss Mr. Hart (Dabney Coleman); Judy Bernly (Jane Fonda), a wide-eyed divorcee entering the workforce for the first time; and their colleagues dealing with child care demands, unequal pay, and alcoholism. “For the first time on screen, you saw exactly what was happening in offices,” says Dame Jenni Murray in the 2022 documentary Still Working 9 to 5. And that was unpaid labor beyond the job description, like getting coffee at best and sexual harassment at worst. “I’m not your girl, your wife, or even your mistress,” Violet hisses at Mr. Hart, alluding to the office rumor that he’s been having an affair with Doralee. The characters also take on what Violet calls the “pink collar ghetto” of clerical work; she is continually passed over for a promotion in favor of the men she trained who need it more because they have families to support, and “clients would rather deal with a man.” As far as we like to think we’ve come, Fonda notes in the documentary, “It’s worse now. Where do you go to complain when you’re part of the gig economy?”  FONDA, EARLIER THIS MONTH AT THE DNC WINTER MEETING FOR STAND U FOR A LIVING WAGE. (VIA GETTY IMAGES Audiences ate it up: 9 to 5 was a box-office success, earning over $100 million on a $10 million budget, and was the second-highest-grossing movie of 1980 behind The Empire Strikes Back. A precursor to Bridesmaids and Girls Trip, 9 to 5 proved that the female-ensemble comedy was bankable. Violet, Judy, and Doralee see power in the collective, realizing that they are stronger together. They kidnap their boss, and the changes they enact in Mr. Hart’s absence—flexi-time, job sharing, office daycare, and disability accommodations (equal pay is a bridge too far)—show what a truly egalitarian (excuse me, ruined) workplace can look like. Doralee’s plotline also presages the #MeToo movement in 2017, when sexual harassment in the workplace was revealed to be all too common. (In an ironic turn of events, the 2009 Broadway musical adaptation of 9 to 5 was produced by Harvey Weinstein.) Judy, Doralee, and Violet briefly toy with publicizing Mr. Hart’s sexual harassment, but they ultimately believe no one would care. Forty-five years later, the problems in 9 to 5, as exemplified by the #MeToo movement, are stubbornly around, while other problems have popped up alongside them: the mass exodus of women from the workforce, the DEI backlash, the arrival of AI, and the cost-of-living crisis have all made work even more precarious. “No one should work full time and still have to choose between rent, food, or childcare,” Fonda said at a Stand Up for a Living Wage fundraiser earlier this month. “Low wages are not distributed equally. They fall hardest on women and especially women of color who make our restaurants, hospitals, and service industries function every single day. When we raise wages, we directly address gender inequality, racial injustice, and the economic barriers that have held entire communities back for generations.” As Parton sings in the iconic theme song she wrote for the movie, we’re all just “barely getting by, it’s all takin’ and no givin’.” Unfortunately, 9 to 5’s workplace commentary remains as relevant as ever. Luckily, it remains as enjoyable as ever, too.  WEEKEND READING 📚🎧On the long commute: Turns out getting to work is a lot harder when you’re a woman. (The Atlantic) On love and lust: It was a good year for yearning. (The Cut) On the bots: The online culture wars aren’t what they used to be. (There Are No Girls on the Internet)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Syria's Mothers are Fighting to Rebuild Their Homes

One year after the end of a long war, they tell journalist Tara Kangarlou what coming home has really been like

By Tara Kangarlou

“There are very few mothers here who haven’t lost a child or a spouse, and very few children who haven’t lost a mother or a wife,” says 62-year-old Khadijah as she sits on the floor of a heavily bombed building—flattened, except for the one room where she now lives with her 75-year-old husband, Khaled. Like most of her neighbors, Khadijah, her husband, and her children—previously displaced across Syria and neighboring Lebanon and Turkey—are now returning to their devastated hometown of Zabadani, wondering how to pick up fragments of a life uprooted.

The nearly 13-year-long war in Syria is known as one of the worst humanitarian crises of the 21st century. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the conflict displaced more than 13 million Syrians, including the six million people who fled to neighboring countries. For years, the war functionally dismantled the country’s healthcare and infrastructure and robbed an entire generation of school-aged children of their childhood and education—losses that ripple through every fabric of Syrian society today. The UN Human Rights Office has documented over 300,000 civilian deaths, with some estimates approaching half a million. Multiple mass graves have been found across the country, and Bashar al-Assad’s deployment of chemical weapons in Ghouta and Duma against his own people marked the deadliest use of such agents in decades.

This month marks a year since the fall of Bashar al-Assad, and over that time, millions of Syrians have been adjusting to their newly liberated reality. More than four million have made their way back to their villages across Syria—their homes reshaped by years of siege, bombardment, and civil war. In Zabadani, Eastern Ghouta, Madaya, Duma, and other hard-hit regions across the country, mothers—like Khadijah—are navigating these losses firsthand as they work to restore a semblance of stability for their families.

It should be a time of celebration, but for those living among the remnants of destruction, grief is pervasive. “Before the war, I would always wear white, but ever since the first death in our family, I’ve not taken off my black scarf,” Khadijah says. “I continue to be in mourning,”

Like so many others in Syria’s Zabadani region, Khadijah and her family hail from generations of experienced, hard-working farmers. But the land, once celebrated for its apple orchards, vineyards, and lush farmland that helped feed Damascus, endured one of Syria’s longest and most punishing sieges. Between 2015 and 2017, barrel bombs, airstrikes, and artillery shells rained down, destroying irrigation systems, flattening farmland, and contaminating the earth with heavy metals, TNT, and fuel residues. The blockade also choked off agricultural inputs—seeds, fertilizers, and clean water, leading to the collapse of a once-thriving rural economy.

“We’d feed an entire town with our fruits and vegetables, but now, we barely have enough to feed our own family,” says Khadijah, whose grievances are evident when you visit her farm, where the soil is depleted and infrastructure destroyed.

“The only people whose farmland was spared were the people who cooperated with the Assad regime,” Khadijah explains. “We’re grateful to be alive, and we will rebuild, even though right now, we just don’t know how.” Later, she recalls the harrowing days in 2015 when she, her two daughters, and her then two-year-old grandson, Ammar, were displaced to nearby Madaya as the Assad army besieged Zabadani. Soon, those under siege in Madaya were facing severe food shortages and starvation under a blockade imposed by Assad’s forces and his allies Russia and Iran-backed Hezbollah.

“Ammar’s father [my son-in-law] was just killed…when we were forcefully moved to Madaya,” she says. “We had so much grief. “For the nearly two years that followed, we had nothing to survive on except rationed sugar, bread, and at times animal feed and grass.”

It wasn’t until 2017, following months of siege, that Khadijah and her family were relocated to opposition-held Idlib where they continued to live in displacement with little means to support the family.

Now 22, Ammar is studying to be a medical technician in Idlib—a city that remained the only lifeline for hundreds of thousands of displaced Syrians during the war. Visiting his grandparents in Zabadani, he brings in freshly made Arabic coffee and sits next to his grandmother and 37-year-old uncle Omar, who lost an eye in the war. Both men look at Khadijah with deep respect and endearment. “Every single mother in Syria has suffered tremendously, including my own mother and my grandmother; but we are of this land, and we’re happy to be back,” said Ammar.

The Flowers Still Bloom

Across Syria, the devastating impact of warfare is as environmental as it is emotional.

Just an hour’s drive from Damascus, 35-year-old Hiba walks through her hometown of Duma in Eastern Ghouta, stopping at a perfume shop to buy rose-scented oils—a defiant joy after surviving years of siege, bombardment, and chemical attacks. “Everything above ground was destroyed,” she says, recalling giving birth during the war in a half-collapsed clinic with no medicine, water, or electricity. Today, Hiba calls her 7-year-old daughter, Sally, her best friend and the person who makes life meaningful. “She loves riding her scooter and wants to be a pharmacist,” Hiba shares.

During the war, inspired by her family’s struggles caring for her younger brother with Down syndrome, Hiba began working with children with special needs—a profession she continues to this day, despite her own personal battles.

“People were disconnected from the world,” she says, pointing to what once was her house—a collapsed building lying under the weight of repeated barrel bombs and artillery strikes. “Our country is destroyed, but we mustn’t forget what happened to us. Our children must remember everything—so it doesn’t happen again.”

Both Zabadani and the Eastern Ghouta regions stand as stark evidence of how siege warfare and chemical weapons became tools of collective punishment—obliterating not just lives, but the ecosystems and livelihoods that sustained millions of ordinary civilians, including mothers, who are now searching for hope amidst rubble.

Back in Zabadani, 35-year-old Lana—a mother of two toddler boys—walks the grounds of her grandfather’s house and what was once her safe haven as a child.. She is a psychologist who has recently returned to her flattened town after years of life as a refugee in Lebanon. Today, along with her husband, she’s back “home,” doing what she once dreamed of doing for her own people and community.

“This is my grandfather’s home. My daddy grew up here,” she says. “We used to play here as children.”

The building’s walls are pocked with shrapnel holes and its ceilings blown down into rubble, but as we climb up and walk into the remnants of the house, she suddenly turns around, tearing up. On a half-collapsed wall, a faint drawing survives—painted decades ago by Lana’s father as a child, and depicting a red house surrounded by trees and a bright blue lake—the last fragile trace of a family’s life before war.

“My daddy was an artist. I have to tell him this is still here.” She looks at the flowers growing from underneath a pile of stones and smiles: “See, even in the middle of this destruction, we still have flowers bloom. There is hope, Tara. We are here.”

Tara Kangarlou is an award-winning Iranian-American global affairs journalist who has produced, written, and reported for NBC-LA, CNN, CNN International, and Al Jazeera America. She is the author of The Heartbeat of Iran, an Adjunct Professor at Georgetown University, and founder of the NGO Art of Hope.

"A revolution has begun. There is no going back."

On the anniversary of the Beijing women’s conference, a blueprint for a brighter future

Thirty years ago this month, women from around the world gathered for a conference that made history and, as it turned out, would not happen again. The 1995 UN Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing was a monumental moment for activists and world leaders who came together to “answer the call of billions of women who have lived, and of billions of women who will live,” as the first female Prime Minister of Norway, Gro Harlem Brundtland, put it at the time. It’s the meeting at which then-First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, building on years of women’s organizing, famously said, “Women’s rights are human rights,” which made global news because it was (and apparently remains) a radical perspective.

The journey to the conference—which is documented in a new multimedia project from the United Nations Foundation and co-produced by The Meteor—was two decades long, with previous meetings held in Mexico City, Copenhagen, and Nairobi. Beijing itself was the largest women’s rights gathering at that point in history, with a massive audience of 45,000 people invested in building a better future. Pulling it off was no small task, but the leaders charged with doing so were more than up to it. Among them was the inimitable Gertrude Mongella of Tanzania, the Secretary-General of the conference, who later became known as Mama Beijing. “A revolution has begun,” she said during a closing speech at the Conference, “there is no going back.”

Mongella was a key player in producing the Beijing conference’s most significant document: The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action—which remains the most comprehensive blueprint for gender equality and women’s rights ever created. It wasn’t just a wish list; 189 countries committed to it in Beijing. It demanded women’s inclusion in government and policymaking; economic policies built with gender in mind; the understanding that violence against women is a human rights violation; and was also one of the first international agreements to demand that governments complete a thorough analysis of how climate change and industrialization had affected women. From the Platform: “The continuing environmental degradation that affects all human lives has often a more direct impact on women…Those most affected are rural and Indigenous women, whose livelihood and daily subsistence depends directly on sustainable ecosystems.”

You probably know how this ends: While some of the Platform’s key goals have been achieved—women’s representation in government, for instance, has risen—many have yet to be fulfilled, 30 years later, not because of an absence of activism, but because of global backlash and competing priorities. But the women at the forefront of global change remain motivated. When asked what the next global feminist conference should focus on, Nyasha Musandu of the Alliance for Feminist Movements put it this way: “We must dare to dream bigger, disrupt deeper, and build bridges across movements. The fight for justice is not just about breaking barriers—it’s about reimagining the world itself.”

Four years of the Taliban

August 14, 2025 Hi Meteor readers, Popping in for the second time this week with a recommendation so fervent, I had to commandeer the newsletter to make it. Last night, I finally saw the Tony-nominated play John Proctor Is the Villain, and I’m still levitating. I cackled with laughter. I cried! The show is set in a high school in rural Georgia, and it unfurls as a class of students reads Arthur Miller’s The Crucible while the #MeToo movement swirls. There are meditations on trust and friendship, jokes about Glee, an epic interpretive dance, feminism club, and such biting, clever dialogue that of course Tina Fey has signed on to produce the movie adaptation. It’s pitch-perfect and brilliant, and here I was thinking 2018 was not a period of time I wanted to revisit at all. If you are anywhere near New York, you must, must, must see it before it closes on September 7. That concludes The Meteor’s Theater Corner. Meanwhile, a special edition of the newsletter below: Today we have a beautiful and moving reflection from Lima Halima-Khalil, Ph.D., who writes to us on the eve of the fourth anniversary of the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, recalling the tumult and horror of that day and sharing her own perspective as a millennial, mom, and researcher in 2020. But first, the news. Stage whispering, Mattie Kahn  WHAT'S GOING ONTaylor Swift, Taylor Swift, and Taylor Swift, for starters. Also, Trump is headed to his much-heralded summit in Alaska, where he’ll meet with Russian President Vladimir Putin. (There will be no showgirls.) Back at home, historians are rightfully freaked out that the White House has expressed a desire to “review” exhibits at the Smithsonian’s museums and galleries, which is the kind of thing that isn’t supposed to happen in democracies. To be clear:  AND:

“Life is Still An Open Wound”Four years after the Taliban seized her country, Lima Halima-Khalil, Ph.D., reflects on the losses, joys, and complexity of life for young Afghans.On August 15, 2021, time did not just stop; it dissolved. One moment, I was at my desk in Virginia, an Afghan researcher piecing together the life stories of Afghan youth for my doctoral research; the next, I was holding my breath between phone calls I could not miss. My computer screen became my only window to my country slipping away: convoys of cars carrying loved ones I could only follow on Google Maps, the low, frantic hum of evacuation messages on WhatsApp, and the heavy silence between each update. That day marked the beginning of the final withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan, following a deal signed with the Taliban that effectively handed the country over to them. The elected president fled, and fear settled like smoke across the nation. Thousands rushed to the airport in blind panic, terrified of what the return of Taliban rule would mean. Many of the young people I had interviewed joined the crowds at the gates along with their families (and mine too), desperate for a flight to anywhere. Between August 15 and the final U.S. military departure on the night of August 30, over 200 people died at or near the airport: some trampled in stampedes, some shot, some who fell from planes, and 182 of them killed in a suicide bombing on August 26.  THE AUTHOR, LEFT, DEFENDING HER PH.D. ON AFGHAN YOUTH EARLIER THIS SUMMER. It is hard to explain how, in an instant, everything that anchors your life, your home, family, career, the freedoms you’ve built over a lifetime, can be stripped away. You are left with two choices: walk through the valley of death into a new world naked without any resources, or stay in darkness, losing every human freedom and shred of dignity under the Taliban barbarism. Every year on this day, I try to tell my story and the stories of hundreds of my countrymen and women. I have never quite managed to capture the full weight of what we lived through, or what we are still enduring. But I know who I am: I am Lima Halima-Khalil, and I know that if we do not tell these stories, we risk losing more than a country; we risk losing the truth of who we were and who we still are. Watching My Country DisappearThat day, as haunting footage of young men clinging to U.S. military planes, their bodies falling through the sky, was shown over and over on TV, my inbox was flooded in real time: “Lima, they’ve reached the city gates.” “My office is closed, they told us not to come.” “Can you help me get my sister out?” I typed until my fingers ached—evacuation forms, frantic emails, open tabs of flight lists—while my mind kept circling back to my sister Natasha. She was 24 when the Taliban killed her with an IED in 2020 on her way to work. Every young woman who called me that August day and over the last four years sounded like her: “Please, Lima, don’t leave me here. Save me.” Somewhere in that blur of urgency and grief, I knew I was watching my country disappear in real time. The words of one young woman—an accomplished artist—still echo: “I wasn’t mourning just a country. I was mourning the version of myself that could only exist in that Afghanistan.” In the months and years that followed, I carried my interviewees’ stories inside me. I felt the humiliation of the young woman who had to pretend to be the wife of a stranger just to cross a border. I felt the fear of the female journalist who hid in the bathroom each time the Taliban raided her office. I felt the silent cry of the father who arrived in a foreign land with his toddler son and wife and wandered the streets in winter, looking for shelter. I had nightmares over a young man’s account of seven months in a Taliban prison, tortured for the “crime” of encouraging villagers to send girls to school. Four years later, August 15 is still an open wound. Afghanistan is now the only country in the world where girls are banned from secondary school and university. Women are barred from most jobs, from traveling alone, from their own public spaces. Half the nation is imprisoned; the rest live under constant surveillance. Believing in ChangeHowever, the past four years have not been made up of grief alone. Even in exile, even under occupation, life has found a way in. I have witnessed many Afghan women earning their master’s degrees in exile. I have seen my young participants inside the country opening secret schools for Afghan girls in their homes and enrolling in online degree courses, while those in exile run online book clubs and classes for girls, refusing to let hope die. I have seen families reunited after being separated for four years. I see Afghan identity and tradition celebrated more than ever. In my own life, some moments reminded me why I still fight: celebrating the birth of my daughter, Hasti; dancing with friends after completing 140 hours of interviews for my PhD; standing on international stages to speak against gender apartheid, carrying my participants’ words across borders; watching my research shape conversations that challenge the erasure of my people. Like the two sides of yin and yang, these years have been both destructive and generative. One hopeless day, I called a participant still in Jalalabad. Halfway through, I asked, “What is giving you hope today?” She didn’t pause: “The belief in change. I don’t believe things will remain like this, where women are not allowed to live with full potential in our country. I will not stop my part, which is to keep studying and to believe that I will be the first female president of Afghanistan.” Hope resides in me, too. This year, on this painful anniversary, I ask the world: the war that began in 2001 was never Afghanistan’s war, and today, it is still not the burden of Afghan women and girls to carry alone. So please, don’t turn your face away. Do not accept the narrative that this is simply Afghan tradition, that women are meant to live like this. That lie has been fed to you for too long. The women and girls of Afghanistan are humans. Until we see them and treat them that way, this gender apartheid will not end.  Lima Halima-Khalil, Ph.D., is the program director of the “I Stand With You” campaign at ArtLords, a collective she co-founded, where she mobilizes global awareness against gender apartheid in Afghanistan. Her research explores youth resilience amid violence and displacement. Her writing has appeared in Foreign Policy, TRT World, and academic publications.  WEEKEND READING 📚

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

They Were Told “Don’t Write, Don’t Post, Don’t Report”

For Iran’s fearless women journalists, every byline is a form of rebellion

By Tara Kangarlou

“To be a war correspondent is like a wounded dove flying through a pitch-black tunnel. It crashes into the walls over and over, but keeps going, for a chance to send the message, to save others,” says Arameh, a 40-year-old Iranian journalist. She and her two colleagues, Samira, 39, and Parvaneh, 27 (all have been given pseudonyms for their safety), are among the many brave Iranian journalists who remained on the ground in Tehran to report on the 12-day Israel-Iran war earlier this summer.

The women work for one of Iran’s prominent news sites, covering social, local, and political issues. Although the outlet is independently owned, it still falls under the heavy scrutiny of the Islamic regime’s watchful eyes. (Out of the utmost caution, we’ve withheld the name of the website.) “Despite slow internet and censorship, we wrote, posted, and published” throughout the war, recalls Arameh. “With images of blood and death flooding in, we kept reporting.”

Ultimately, Iran’s missile attacks on Israel killed 28 people and wounded more than 3,000, some of them civilians. Israeli airstrikes on Iran killed more than 1,190 people and injured 4,475, according to the human rights group HRANA. As in many conflicts, Western coverage of the war zeroed in on geopolitics: the Islamic Republic’s hardline rhetoric, the regime’s nuclear ambitions, and the fate of a theocracy teetering on the edge. Yet beneath those soundbites, a generation of fearless, tenacious young journalists—many of them women—tirelessly documented life under foreign bombardment and domestic censorship in the world’s third-largest jailer of journalists.

According to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), more than 860 journalists have been arrested, interrogated, or executed in Iran since the 1979 revolution, which brought the Islamic Republic to power. RSF also reports that since Mahsa Amini’s killing in September 2022, at least 79 journalists, including 31 women, have been detained—with some still behind bars. The International Federation of Journalists and Iran’s own Union of Journalists report even higher figures, estimating that over 100 journalists have been detained during this period, most in Tehran’s notorious Evin Prison. Among those held were 38-year-old Elaheh Mohammadi, her twin sister Elnaz, and Niloofar Hamedi, who first broke the news of Mahsa Amini’s killing for Shargh Daily in September 2022.

My connection to these women goes beyond our shared profession—I was born and raised in Iran and immersed in all the complexities of its everyday life; but today, as an American journalist with dual nationality, I can no longer return freely to my country of birth—simply because my profession is deemed threatening to the forces at home. I often have nightmares of being arrested in Iran or of never again seeing my childhood home; but what gives me hope is the strength of women like Arameh, Parvaneh, and Samira, who stayed. They do so knowing their government is always watching, listening, and ready to punish them for telling the truth.

These women were not just covering a war; they were surviving it.

On the war’s second night, 27-year-old Parvaneh tried sleeping in the newsroom as her home was in an evacuation zone. It was just her and the office janitor, whose pregnant wife and daughter had already left the city after their neighborhood was hit. That night, Parveneh recalled, “the sirens were so loud that neither one of us could sleep, so I stayed up all night and covered the strikes.”

On day three, Arameh convinced her aging parents, brother, sister, and five-year-old niece to leave Tehran without her. “With each strike, I’d tell my niece it was a celebration or fireworks,” she recalls, heartbroken that the little girl believed her each time.

Similar to many other journalists and photographers in the country, Arameh and her colleagues received anonymous calls from intelligence agents and government officials warning, “Don’t write. Don’t post. Don’t report.” But as always, they did. Samira reassured her mother, whose brother was killed in the Iran/Iraq war in the 1980s, that she would not leave Tehran. “I’m a journalist,” she explains. “If I’m not here in these days, it would be like a soldier abandoning the battlefield.”

“We adapted; we always do,” Arameh says. “We stopped giving exact locations or numbers. Instead, we reported where sirens were heard. We told people how to protect their children. In times of war, a journalist must also be a source of empathy.”

For journalists in Iran, adaptability is a necessary skill as they navigate censorship, surveillance, and threats from a regime that has long waged war on its own press. These women documented both the human devastation of the war—including the Tajrish Square bombing that left 50 dead—but also the ongoing intimidation from the state toward members of the press. That intimidation extends to those who defend journalists as well. Human rights lawyers such as Nasrin Sotoudeh, Taher Naghavi, and Mohammad Najafi have been imprisoned for the “crime” of representing journalists and activists.

“My beautiful Tehran felt like a woman who had been brutally violated; battered, broken, bleeding,” says Samira, recalling the last night of the war. “It was the worst bombardment; something inside us died, even as the ceasefire began.”

On June 23, just one day before the ceasefire that would end the war, Israeli airstrikes hit Evin, killing at least 71 people—among them civilians, a five-year-old child, and political prisoners, including journalists. Nearly 100 transgender inmates are presumed dead—all people who should never have been there from the start.

The world often celebrates Iranian women in hashtags and headlines, but falls silent when it comes to tangible support. Heads of state, renowned public figures, and human rights organizations call for freedom and justice, but political inaction persists.

“If such strikes happened elsewhere—especially Europe or the U.S.—the world would’ve cried out,” Arameh says. “But in Iran, the Iranian people are always defenseless. People around the world talk about loving Iranians, but…we are once again left alone in our pain.”

Iranian journalists are not asking to be saved. They are asking to be heard, to be respected as the only eyes and ears of millions whose voices have been stolen by a regime that does not represent them. More than anything, these independent journalists, who are not funded by the regime and continue to report under severe censorship and surveillance, are emblematic of a deeper reality: that Iranians—especially women, and especially young people—stand firm in their pursuit of truth, change, and growth, no matter the cost.

Tara Kangarlou is an award-winning Iranian-American global affairs journalist who has produced, written and reported for NBC-LA, CNN, CNN International, and Al Jazeera America. She is the author of The Heartbeat of Iran, an Adjunct Professor at Georgetown University and founder of the NGO Art of Hope.

A Global Backlash Against Women

March 6, 2025 Hello, sweet Meteor readers, I live in the tundra, a.k.a. upstate New York, and to us, 50-degree days like the one we’re having today pass as signs of spring. That, and when my kid starts to come home from preschool covered in mud. It’s happening, y’all. Bring on the dirt.  Today, on the occasion of International Women’s Day, we take the temperature of women’s rights around the world. Plus, some good news for abortion, gender-affirming care…and your brain. Thawing out, Nona Willis Aronowitz  WHAT'S GOING ONA global backlash: International Women’s Day, celebrated every year on March 8, is always a good excuse to take stock of how women and girls are doing around the world. Two new reports confirm that there’s data behind what we can clearly see: There’s been a palpable backslide. A new poll conducted by Gallup in 144 countries asked participants, “Do you believe women in this country are treated with respect and dignity, or not?” and found that in 93 countries, women are much less likely than men to say yes. Echoing this data, a new report from UN Women has found that, precipitated by factors like COVID and political polarization, one in four nations reported that backlash impeded progress on women’s rights in 2024.  INTERNATIONAL WOMEN'S DAY RALLY IN NEW YORK CITY, 2018 (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Looking closer at Gallup’s results for the United States in particular, tells us a lot about how gender dynamics have changed here in the last decade or so. In 2012, a full three-quarters of women and 80% of men agreed that women in this country are treated with dignity and respect. Now, those numbers have plunged to 49% and 67%, respectively. That not only points to a huge gender gap in how respondents think women are treated (implying, perhaps, that men are not paying attention?) but a sharp decline overall. In fact, these percentages are the lowest in the United States since Gallup started these polls 20 years ago. So: Are they a bleak reflection of ways life has actually gotten worse for women since the fall of Roe v. Wade, the rise of far-right misogyny, and more? Or do they also show the rise in awareness of sexism and misogyny (a good thing)? For many women and some men, wake-up calls—like #MeToo and Trump’s two wins over two women—may have smashed any illusions of gender equality. Sexual harassment in the workplace was just as bad in 2012, for instance, but maybe now we’re more likely to notice it. Still, the data does make clear that when respondents say women are more likely to live without respect and dignity, they’re often right. The UN Women report found that in the last few years, discrimination against women and girls has risen, legal protections have lessened, the number of women and girls living in conflict has spiked by 50 percent, and funding for programs that support women has withered. If you’re looking for signs of progress, there are some: The report found some improvements over the last 30 years, like greater parity in education, one-third fewer maternal deaths, higher representation of women in parliaments, and more than 1,500 legal reforms striking down discrimination in 189 countries and territories. In a sliver of good domestic news, Pew Research Center also found in a recent survey that the pay gap has narrowed slightly in the United States. So the news isn’t all bad—but it’s a clear indication that progress isn’t linear and that we have a long way to go. The Gallup poll’s gender gap is most pronounced in young people; only 41% of young women think they’re treated with dignity and respect, as opposed to 63% of young men. This is depressing on one level but heartening on another: At least young women’s eyes are wide open to the work they still have to do. It’s an open question when and whether their male peers will get on board. AND:

REPRESENTATIVE AL GREEN DOING WHAT MANY OF US WISH WE COULD DO: YELL AT DONALD TRUMP. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

WEEKEND READING 📚On hypocrisy: A pediatrician who left her seven-year-old daughter behind in the States to care for war-wounded children in Gaza confronts the monstrous lopsidedness of Western media covering the conflict. (LitHub) On loss: A mother writes a eulogy for her beloved Altadena house, which burned in the L.A. fires—and for a world in which the consequences of climate change seem remote (Romper) On reparations: Mina Watanabe explains the history of “comfort women”—a euphemism for women who were sex slaves for Japanese troops in the ‘30s and ‘40s—and what justice would mean for them. (New York Times)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()