"This Changes Everything"

February 6, 2026 Happy Saturday, Meteor readers, We’re coming to you with a special treat from the archives today, in honor of the 100th celebration of Black History Month this February. Four years ago, our colleague Rebecca Carroll sat down with author and historian Imani Perry to discuss the surprising origins of Black History Month and its current role in the American story. When we first published this piece, we noted that legislators were trying to strip Black history lessons from school. Some of those efforts are now law, but advocates, educators, and avid readers remain undeterred. And I suppose that’s the history lesson in and of itself—the harder you try to erase it, the stronger it becomes. Love and power, Shannon Melero  “This Changes Everything”What Imani Perry taught me about Black History MonthBY REBECCA CARROLL  THE INCREDIBLE IMANI PERRY WAS HONORED AT THE 2025 WOMEN'S MEDIA CENTER FOR HER BODY OF WORK (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Years ago, when I was working at a mainstream media corporation, I was called into a marketing meeting for my ideas on how to best package Black History Month in ways that would boost ad sales and sponsorship on the site. I suggested, in all seriousness, because I genuinely believed what I was saying: "What if we didn’t package Black History Month at all? What if we took a break from selling this idea that Black History is something we should only think about for a month every February?" I was promptly dismissed from the meeting. The thing is, I was coming from a place of profound (and uneducated) cynicism, based on the belief that Black History Month was created by white folks. And I know I’m not alone in thinking this. Thank heavens for historian and author Imani Perry, whose book, South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation, covers this terrain, and who went ahead and set the record straight for me—because honestly, I simply did not know. Rebecca Carroll: Given that I was adopted into a white family, raised in a white town, and then went on to spend the bulk of my career in white media spaces, Black History Month has always seemed exploitative and commercialized to me—but I was so curious to learn from you that Black History Month actually has its origins in Black culture. Can you explain? Imani Perry: Black History Month was an outgrowth of Negro History Week. In the early 20th century, Black history programs and curricula were organized in segregated Southern Schools. They happened in February because that was the month of Abraham Lincoln's birth and Frederick Douglass's chosen birthday (he didn’t know his exact birthdate, having been born in slavery). In 1926, historian and organizer Carter G. Woodson formalized these practices and established Negro History Week [in February].  A COLORIZED PORTRAIT OF CARTER G. WOODSON, THE FATHER OF BLACK HISTORY MONTH (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Negro History Week was an extension of a very deliberate effort that began immediately post-emancipation to document Black history…and resist the false claim that people of African descent had contributed nothing meaningful to human history or civilization. Negro History Week, which became Black History Month in the early 1970s, was focused on young people…and became a robust tradition. There were Negro History Week curricula—books on Black U.S., Caribbean, and African histories and historic figures; essays, documents, plays, pageants, and academic exercises along with the ritual singing of "Lift Every Voice and Sing." Often, these school-based programs invited the entire community to participate, and so these were collective celebrations, as well as opportunities for people to learn. It wasn’t really until the late 1970s that white Americans even began to have any significant awareness of Black History Month, and much of that came through consumer culture. So, [as with] Kwanzaa, a ritual that was developed primarily within Black communities made its way to the larger public through advertising strategies intended to compel Black buyers rather than [achieve] substantive political transformation. So we get fast food companies celebrating Black History Month in ways that mean close to nothing or, at times, are even offensive. But despite that, there continue to be institutions in which Black History Month is rooted in a tradition of Black people writing themselves into history in ways that reject the logic of white supremacy and give a more expansive reach to the story of Black life both in this country and globally. And so what does Black History Month mean to you, both personally and professionally? Personally, Black History Month is one of those traditions, like Emancipation Day or Juneteenth or Watch Night, that I cherish because it anchors me in tradition and ritual. Professionally…because I’m very invested in ensuring that my students know the history of Black institutional life, I teach the ritual as an outgrowth of one of the most important periods of intellectual development in African American history. Traditionally, historians describe the Jim Crow era as the "nadir" of American race relations, the phrase used by historian Rayford Logan. And by that, he meant the lowest point, that horrifying period when the promises of Reconstruction had been completely denied. What is remarkable about that time is that Black people got to work despite the devastation. There was exceptional growth in African American civic life in this period. People were building organizations and networks, writing books and developing social theory, building schools, and churches at every turn. And so, even when society shut the door to opportunity and treated Black people with horrible brutality, they kept dreaming, doing, and creating. For me, that is not just a key point for understanding African American history, but it is an incredible daily inspiration for my own work. Do you think it's ever more necessary in this current cultural climate to uphold BHM, and if so, to what end? I don’t think of Black History Month as more or less important based on the political moment. I guess I would say it will be important indefinitely because we live in a white supremacist country and world, and counter-narratives that value freedom and dignity and resilience will always be necessary as long as stratifying people on the basis of identity is the norm. Surely you’ve had experiences where (almost always white) people will say something that is just all kinds of wrong regarding BHM—I’m sorry to say I have had several—or there is this unspoken sense of "We’re giving you this whole month, can you just be grateful?" Can you recall such an experience, and how you responded/flipped the script for your own sense of sanity? Thank goodness I've never had a white person say to me that they’ve given Black people Black History Month. It would frankly be something that I'd laugh at for a long time. Nothing could be further from the truth. Black people created it for Black people, and particularly for Black young people, and have been gracious enough to invite others to participate. They should feel fortunate.  ENJOY MORE OF THE METEOR Thanks for reading the Saturday Send. Got this from a friend? Don’t forget to sign up for The Meteor’s flagship newsletter, sent on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Party Like It's 1946

January 29, 2026 Salutations, Meteor readers, I’m in my nerd-girl history bag today—let’s get to it! Ahead of a planned general strike tomorrow, we take a look at civic actions of yesteryear and what we can learn from them now. Plus, Rebecca Carroll on Broadway’s “Liberation.” On the picket line, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONShut it down: Tomorrow, activist groups, student associations, labor unions, businesses, and regular people across the country will be protesting ICE by staging a national shutdown via a general strike: “no school, no work, and no shopping.” Leftists and even some establishment Democrats have long yearned for a sweeping general strike, and the impact of Minneapolis’s version last week has made the prospect seem more possible. But many who’ve lost hope may be wondering: How can anyone pull this off? Do these things even work? You don’t have to look too far back to answer those questions. We saw the power of a general strike in Puerto Rico in 2019 when the people ousted a corrupt governor. In 2024, South Koreans held a general strike as a direct response to President Yoon Suk Yeol’s declaration of martial law. But the last time the U.S. mainland truly saw general strikes grind businesses to a screeching halt was in 1946. It was known as the greatest wave of strikes in American history, with over 4 million workers withholding labor in Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Texas, New Jersey, and California. The workers demanded better pay, safer working conditions, and an end to unfavorable union deals that came as a result of post-war economic policies. Entire industries were brought to their knees.  THE YEAR OF THE STRIKE, WHICH FIRST CAME TO LIFE AT THE END OF 1945, IMPACTED WORKERS ACROSS INDUSTRIES. IN NEW YORK, WORKERS WENT ON STRIKE IN JANUARY FOR FAIR WAGES FROM WESTERN UNION. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) The largest general strike that year happened in Oakland, California—and it was kicked off by a small group of determined women. During World War II, to replace men who had been enlisted, women took union jobs in shipyards and factories. But when the war ended in 1945, they had to give up those jobs for returning soldiers. Women who wanted or needed to continue working ended up in retail, where there were no unions and few labor protections. At Kahn’s Department store, workers were forced to endure a demoralizing “Ready Room,” where on-call workers would spend unpaid hours waiting for work that sometimes never came. In October of that year, women (and some men) retail workers organized a strike that was 400 strong. After violent face-offs with the police, the strike ballooned to more than 100,000 workers from various industries, effectively shutting down a major city for two days. The bars were allowed to stay open, on the condition that they put their juke boxes on the sidewalk to play for no charge; the hit song “Pistol Packin’ Mama, Lay That Pistol Down” filled the streets. “People who worked throughout the War had been taking all this crap from employers in the name of the war effort,” Stan Weir, who was an organizer for the United Auto Workers at the time and joined the strike in Oakland, recalled in a 1990 interview. It was “that kind of phony patriotism, instead of real patriotism.” (It’s a distinction worth revisiting in an era when some people define “patriotism” as weaponizing fear, white nationalism, and violence.) The government was so shaken by the events of 1946 that the following year, Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act, which severely limited unions’ abilities to authorize general strikes. Meanwhile, the Oakland women were beaten, mocked, and ignored. But they kept going, and in May 1947, after what probably felt like months of hopelessness, Retail Clerks Local 1265 was recognized. The general strike they inspired in their city changed the course of history. So, could a mass shutdown on Friday really change anything? The proof is in the past. AND:

What If We Centered Black Women in the Story of “Liberation”?A conversation with the women behind the Broadway playBY REBECCA CARROLL  CARROLL IN CONVERSATION WITH THE STARS OF "LIBERATION" AND GLORIA STEINEM. (COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR) Bess Wohl’s critically acclaimed play “Liberation” will take its final bow this Sunday. The Broadway show is a nuanced retelling of the feminist movement through the lens of an unnamed adult daughter seeking to understand her late mother, Lizzie, a journalist in 1970s Ohio. Lizzie (Susannah Flood plays both mother and daughter) is white, of course; stories from the feminist movement seem to almost always center white women. To Wohl’s credit, the play includes a few clear nods to the historical exclusion of Black women from the movement. There are two Black characters: Celeste (Kristolyn Lloyd), a book editor who is part of Lizzie’s consciousness-raising group, and Joanne (Kayla Davion), a working mother who is very much not part of the group. Still, these two Black women are pitted against each other in a key moment, wherein Joanne questions Celeste’s motivations for being part of the all-white women’s group. The scene concludes with Lizzie bringing it back to herself. I wanted to talk about it all, so, along with my colleagues at The Meteor and the extraordinary support of feminist icon Gloria Steinem, I moderated a talkback with Lloyd, Davion, Wohl, and much of the cast at Steinem’s home in Manhattan. On what feminism means to them: Davion: It’s about the confidence in my own skin…What does it mean to be alive? I can't talk about being alive without mentioning feminism. Wohl: I love what you just said, Kayla…as I’ve gotten older, I’ve started to wonder how big can the definition of feminism be without losing meaning. How expansive can we make it? On why it’s so hard for Black women and white women to do feminism together: Davion: I code switch. Like, every day. So that means that I can’t live in the fullness of myself. [It’s often said or implied that] I should be doing something else, that there’s a more professional way of doing things, that my hair should be a specific way. But what does that have to do with the things that I have to say as the person that I am? I feel like we haven’t come into the real understanding of acceptance, because there’s still this idea of what it looks like to be a modern-day woman. Lloyd: The system allows for women who are not Black to experience much more ease. When it actually comes to fighting the fight and getting uncomfortable, they don’t know how. On how the actors approached their roles: Davion (who plays a white woman, Lizzie’s mother, in one scene): I was terrified…As a Black woman, knowing that this audience is about to watch me transform into a white woman, the first thing I'm thinking of is ‘I don’t wanna be targeted.’ I don't want people to think, ‘Why is this Black girl doing this?’ And for Black people, I don’t want them to look at me and be like, ‘Now Kayla, why?’ Lloyd (who grew up in a predominantly white community): On occasion, it does feel like a re-traumatization…[I’ve] been in therapy for healing from having to be in all-white spaces, and then [I] have to be the only one in this all-white space on stage telling the story of this woman who I don't imagine in New York spends much time in all-white spaces. She’s also being re-traumatized being back in Ohio, where she has to be closeted [as a lesbian] and there's no other group for her to express herself in. So, I find that I am able to pull on old feelings, which is why my ritual for getting out of Celeste is very specific. At the end of every show, I have to shower the smell of Celeste off. Before we go into the show, I tell myself: ‘You’re not a race traitor. Some woman out there is gonna be liberated because she sees you.’ There is something you have to turn on as a Black woman, and kind of, like, lower down when you’re in that space…these women are not gonna be able to meet you where you’re at. They just don't know your experience. They don’t have your skin.  WEEKEND READING 📚On the needles: Resistance knitting is back. (Slate) On (not) all women: Dayna Tortorici digs into feminism’s 200-year-old history of infighting. (n+1) On human rights: The Taliban outlawed all forms of birth control in Afghanistan. Women are being “broken” by pregnancies and untreated miscarriages. (The Guardian)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

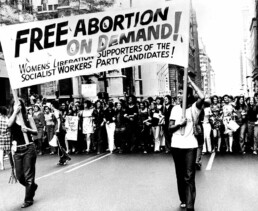

What activists knew when Roe was decided

January 22, 2026 Hi, lovely Meteor readers, Today is one of my closest friends’ birthdays, a balm upon a far more bittersweet milestone: the 53rd anniversary of the Supreme Court’s now-overturned decision in Roe v. Wade. At least there’s birthday cake.  Today, we hear from early pro-choice activists on what it felt like that day when Roe was decided (hint: it’s complicated). Plus, some historic Oscar nominations and your weekend entertainment. Stuffing my face, Nona Willis Aronowitz  WHAT'S GOING ONHope and fear: Fifty-three years ago today, the Supreme Court handed down the Roe v. Wade decision. In a 7 to 2 vote, the justices struck down state abortion bans, replacing them with detailed national guidelines based on weeks of pregnancy. Bending to the groundswell of the women’s movement, four states—Alaska, Hawaii, New York, and Washington—had already repealed their abortion bans, and 13 others had expanded exceptions. But Roe made the right to abortion, based on the constitutional right to privacy, protected everywhere. What was that moment like for women active in the movement? In a post-Roe world, it’s easy to imagine that it was a day of unequivocal joy. I was curious, so I sought out some women who remember it clearly—and discovered that the truth is far more complicated. Yes, there was relief. Heather Booth, who’d started an underground abortion service called The Jane Collective eight years before when she was a student at the University of Chicago, remembers thinking: “FINALLY!” After nearly a decade of abortion advocacy, “the fear, hardship and danger for women who wanted to end an unwanted pregnancy would be addressed.” Dr. Wendy Chavkin, who’d occasionally lent the Janes her Chicago apartment and had organized travel for women to get abortions in New York, recalls the period after Roe as “heady days.” She and her fellow student activists felt “hope, determination and a big vision that saw links between gender and racial discrimination.” Shortly after the decision, she became a counselor at the first legal clinic in Detroit and eventually went to medical school to become an abortion provider herself.  WE GOTTA BRING BACK “FREE ABORTION ON DEMAND.” CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES But many feminists were wary of the meticulous pregnancy timetable the Supreme Court had laid out. “I saw it as a serious compromise,” says Carol Giardina, an early member of the women’s liberation movement in Gainesville, Florida, who recalls referring girls in her freshman dorm to abortionists back in 1963. Although the decision did represent “a mighty win for organized feminism-people power,” she says, her cohort had been “fighting like tigers for repeal of any and all laws on abortion.” That demand, remembers Alix Kates Shulman, radical feminist and author of Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen, sprung out of the worry that “any law would contain restrictions on full reproductive freedom and be vulnerable to constant attack. Which is precisely what happened.” Several women referred me to abortion activist and Redstockings member Lucinda Cisler’s 1970 essay in the feminist journal Notes From the Second Year. States were beginning to introduce laws that legalized abortion, but with exceptions—which, Cisler warned, “can buy off most middle-class women and make them believe things have really changed, while it leaves poor women to suffer and keeps us all saddled with abortion laws for many more years to come.” The only option, she argued, was total abolition of laws restricting abortion. And then there were the women who had other things on their minds. “I’m sorry to say I shrugged at Roe,” says Loretta Ross, who went on to be cofounder of SisterSong and one of 12 architects of the theory of reproductive justice, which encompasses far more than the right to abortion. In 1973, Ross was a teenage mother suffering from acute pelvic inflammatory disease as a result of the infamous Dalkon Shield IUD; instead of removing her IUD, a white, male OB/GYN misdiagnosed her for months until her fallopian tubes ruptured and she was forced to undergo sterilization. She’d had a “perfectly safe legal abortion” several years before in Washington, D.C.; “it wasn’t my lived experience to be denied.” So “while other people were celebrating Roe,” she recalls, “I was having the classic experience of a Black woman whose white doctor was deciding she doesn’t need to have any more kids.”  LORETTA ROSS IN 2022. CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES Although she wouldn’t read it until years later, Ross cited a 1973 editorial by the National Council of Negro Women’s Dorothy Height, who sounded a cautionary note about Roe v. Wade and its potential to worsen state control over Black women’s bodies: “We must be ever vigilant that what appears on the surface to be a step forward, does not in fact become yet another fetter or method of enslavement.” Ross’s sterilization led her to file (and win) a lawsuit against Dalkon Shield manufacturer A.H. Robins, and devote her life to bodily autonomy in all forms. If we don't “intersect race, class and gender,” Ross says, we’ll “never understand the full impact of Roe.” In our new landscape, after Dobbs, many activists are starting to come around to the idea that restrictions and exceptions have no place in abortion care. (They’ve succeeded in getting pro-choice states like New York, whose law goes further than Roe, to agree.) These early activists remind us that perhaps our north star shouldn’t be restoring Roe, but to wrest our reproductive justice out of the hands of politicians—and into our own. AND:

RUTH E. CARTER IN AN EXTREMELY TACTILE PIECE OF CLOTH. CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES

WEEKEND READING, WATCHING, AND LISTENING 📖 👁️ 🔊On a complex heroine: On the occasion of the Roe anniversary, I rewatched “AKA Jane Roe,” a documentary on the case’s plaintiff, Norma McCorvey…and seriously, wow. (FX) On cop-hating: A close read of an uncollected Joan Didion essay asks the question: What made her consign the piece to obscurity? (Dispatches) On heteropessimism: I am embarrassingly late to Heated Rivalry but maybe you are too, and would enjoy Tracy Clark-Flory and Amanda Montei discussing the show as an escape from heterosexuality. (Dire Straights)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

"A revolution has begun. There is no going back."

On the anniversary of the Beijing women’s conference, a blueprint for a brighter future

Thirty years ago this month, women from around the world gathered for a conference that made history and, as it turned out, would not happen again. The 1995 UN Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing was a monumental moment for activists and world leaders who came together to “answer the call of billions of women who have lived, and of billions of women who will live,” as the first female Prime Minister of Norway, Gro Harlem Brundtland, put it at the time. It’s the meeting at which then-First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, building on years of women’s organizing, famously said, “Women’s rights are human rights,” which made global news because it was (and apparently remains) a radical perspective.

The journey to the conference—which is documented in a new multimedia project from the United Nations Foundation and co-produced by The Meteor—was two decades long, with previous meetings held in Mexico City, Copenhagen, and Nairobi. Beijing itself was the largest women’s rights gathering at that point in history, with a massive audience of 45,000 people invested in building a better future. Pulling it off was no small task, but the leaders charged with doing so were more than up to it. Among them was the inimitable Gertrude Mongella of Tanzania, the Secretary-General of the conference, who later became known as Mama Beijing. “A revolution has begun,” she said during a closing speech at the Conference, “there is no going back.”

Mongella was a key player in producing the Beijing conference’s most significant document: The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action—which remains the most comprehensive blueprint for gender equality and women’s rights ever created. It wasn’t just a wish list; 189 countries committed to it in Beijing. It demanded women’s inclusion in government and policymaking; economic policies built with gender in mind; the understanding that violence against women is a human rights violation; and was also one of the first international agreements to demand that governments complete a thorough analysis of how climate change and industrialization had affected women. From the Platform: “The continuing environmental degradation that affects all human lives has often a more direct impact on women…Those most affected are rural and Indigenous women, whose livelihood and daily subsistence depends directly on sustainable ecosystems.”

You probably know how this ends: While some of the Platform’s key goals have been achieved—women’s representation in government, for instance, has risen—many have yet to be fulfilled, 30 years later, not because of an absence of activism, but because of global backlash and competing priorities. But the women at the forefront of global change remain motivated. When asked what the next global feminist conference should focus on, Nyasha Musandu of the Alliance for Feminist Movements put it this way: “We must dare to dream bigger, disrupt deeper, and build bridges across movements. The fight for justice is not just about breaking barriers—it’s about reimagining the world itself.”

Is the Last Abortion Haven in the Caribbean Closing?

How U.S. influence has been quietly reshaping access in Puerto Rico

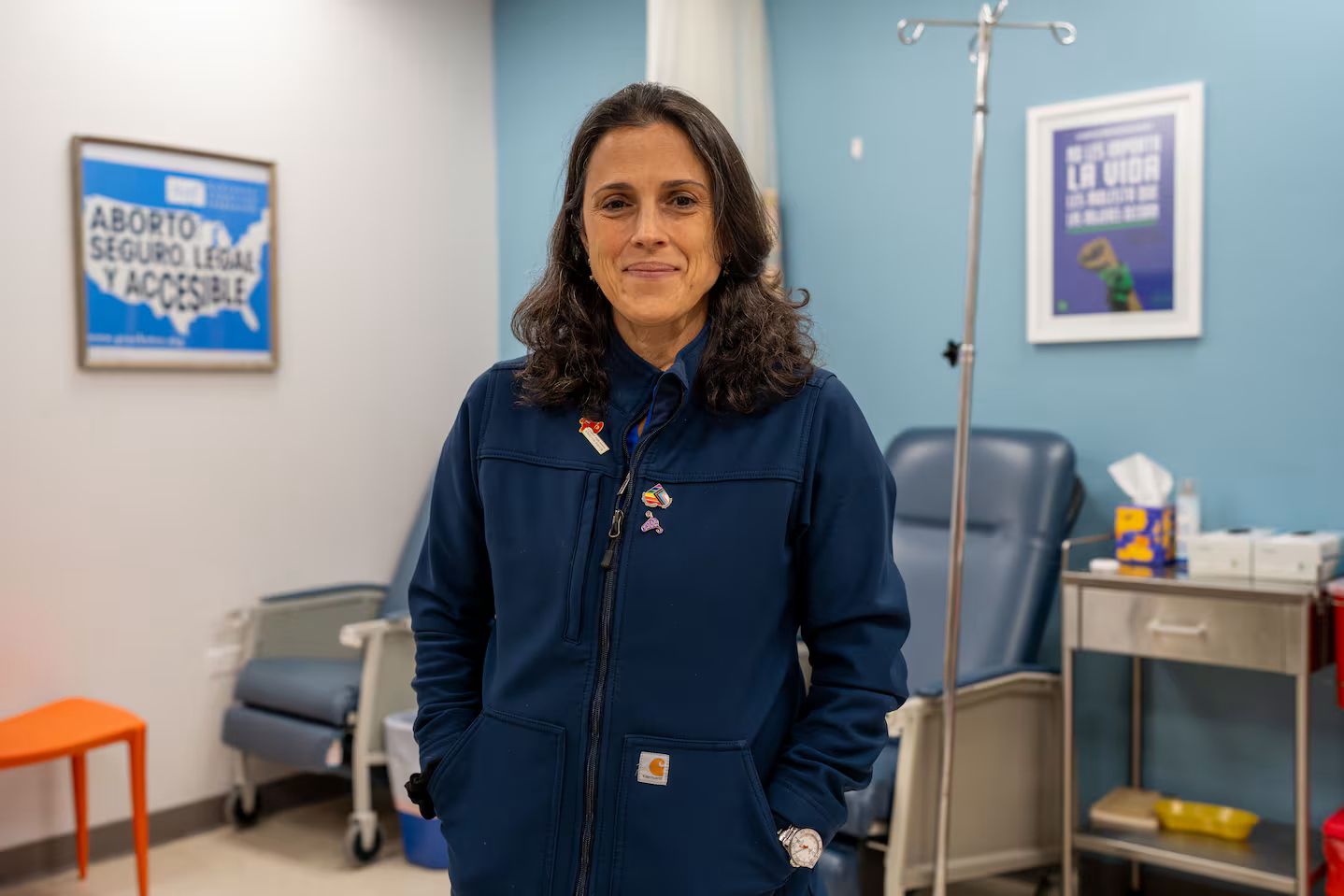

By Susanne Ramirez de Arellano

Dr. Yari Vale's petite frame is no longer weighed down by the nine-pound bulletproof vest she wore when anti-abortion threats increased after the end of Roe v. Wade, but she hasn't gotten rid of it. The security guard at Dr. Vale's Darlington Medical Associates clinic in Río Piedras is no longer at the door; still, she has him on standby. With the return of Donald Trump to the White House and Jenniffer González, a Trump devotee, in the governor’s seat, Dr. Vale is bracing for an escalation in the fight to safeguard reproductive rights in Puerto Rico.

The predominantly Catholic island is “on paper one of the most accessible places in the Western Hemisphere” to obtain an abortion, NPR reported just after Roe was overturned. But with the U.S.'s shift toward right-wing Christian nationalism, that could be changing.

Dr. Vale, an OB/GYN at the Darlington clinic—the only one of the island's four that does late-term abortions—is on the frontline of the fight to keep what’s happening in the United States from happening in Puerto Rico, euphemistically called an unincorporated territory (it's a colony, really). It's a battle that, she says, feels like “throwing a firecracker up in the air, and it's just smoke and no one hears you.” But she persists, knowing that the first line of defense is the clinics.

The Legacy of Pueblo v. Duarte

For years, Puerto Rico has been known for its liberal abortion laws: The right is enshrined in the island’s constitution (which exists separately from the U.S. Constitution) and is protected by the right to intimacy under Puerto Rico’s penal code. Abortion is legal on request if it is performed (or prescribed) by a physician to protect the pregnant woman’s life or health—and health includes mental health. There are no limits (abortion may not be banned before viability; post-viability abortions are permitted for the preservation of the pregnant person), and the procedure doesn't require the consent of partners, ex-partners, or, in the case of minors, parents.

However, these laws have their roots in a dark colonial history. In 1902, four years after invading the island, the U.S. enacted policies to control the population, although abortion was still prohibited without exception. Then, in 1937, colonialists who wanted to further limit the Puerto Rican population passed legislation based on racist neo-Malthusian and eugenic theories, virtually legalizing abortion on the island if it was to protect the life and health of the patient. These changes later facilitated clinical trials of the contraceptive pill and mass coerced sterilizations—a procedure that became so common that it was known among Puerto Rican women as “la operacion.”

In 1980, a case involving a minor and her doctor went even further, and set up modern abortion law in Puerto Rico. In the landmark Pueblo v. Duarte, Dr. Pablo Duarte Mendoza, who had performed an abortion on a 16-year-old girl in her first trimester, was sentenced to four years in prison. He appealed, and the Puerto Rican Supreme Court agreed with him, stating that through the island’s penal code, abortion is legal if it is performed to save the woman's life or health, including mental well-being.

Like many things on an island impacted by colonialism, abortion access is still limited for everyday Puerto Ricans. A surgical abortion costs $250, and a medication abortion between $300 and $350; meanwhile, about 43% of Puerto Ricans live below the poverty line, and insurance plans on the island do not cover abortion. And in addition to cost, religion and social stigma—the “what-will-my-family-say” factor—serve as deterrents for many women.

The Dobbs Effect

When 2022’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision removed the constitutional right to an abortion in the U.S., it didn’t automatically affect rights in Puerto Rico (unlike on the mainland, where “trigger bans” were in place). In fact, some U.S. women began to travel to Puerto Rico from states with restrictive abortion laws, such as Florida. It was the return of the “San Juan holiday.”

But Dobbs did embolden conservative Puerto Rican politicians and pro-life groups, who saw a window of opportunity and seized it. Shortly after the decision, the right-wing religious party Proyecto Dignidad (PD) adopted the U.S. anti-abortion lobby's blueprint and tried to push through several bills to curtail access to abortion, and even criminalize it. They argued that the end of Roe implicitly negated Pueblo v. Duarte. The Senate ultimately defeated the bills; according to many Puerto Rican legal experts, Pueblo v. Duarte rests on the Puerto Rican penal code, which has no analogy in the U.S. Constitution—and should, therefore, not be affected by Dobbs.

An Ascendant Right-Wing Movement

Abortion-rights advocates warn that efforts to criminalize abortion in Puerto Rico are not over. Traditionally, “the issue of abortion in Puerto Rico has not been the overriding controversy that the anti-abortion and ultra-religious politicians want to make it out to be now,” says Senator Maria de Lourdes Santiago, a lawyer and Senator for the Puerto Rican Independence Party (PIP). But, she says, the anti-abortion campaign orchestrated by Proyecto Dignidad now "magnifies the issue to demonize it."

Founded in 2019, PD has capitalized on its nexus of Catholic and Evangelical churches; the erosion of the traditional duopoly of the pro-statehood New Progressive Party (PNP) and the Popular Democratic Party (PPD); and an increasingly ultra-conservative sector of the population urging a return to traditional values. Even though the party got only seven percent of the vote in the 2024 elections, its influence is strong island-wide, with a campaign that now hinges on the abortion issue.

Proyecto Dignidad Senator Joan Rodriguez Veve, a canon lawyer and face of the populist religious right, has vowed to continue fighting to restrict access to abortion. She recently introduced legislation, PS 297, restricting access to abortion for adolescents under the age of 15. The bill is a carbon copy of one that the Puerto Rican House rejected a year ago. It calls for jail time for any doctor or person who assists a minor in getting an abortion, and a slew of other measures, including forensic interviews of minors seeking an abortion.

The Senate approved the bill in February, and almost everyone I spoke to—politicians, legal experts, and abortion doctors—told me they believe it will pass, even though both pro-abortion and some anti-abortion groups have, for different reasons, voiced their opposition to the measure.

A New Generation Stands Up

At the same time that PD is gaining influence, attitudes about abortion are shifting with the younger generation. Rising numbers of people support abortion rights, and young people have galvanized around the issue, taking to the streets in protest and amplifying groups like Aborto Libre Puerto Rico, Profamilias, and Proyecto Matria, among others. It’s a generation that, unlike its mainland counterpart, grew up without a sense of abortion as a wedge issue.

Most recently, health professionals and activists have spoken out against PS 297, warning that the bill puts women and girls in danger. “What's going to happen here is that young women and those most vulnerable will seek out illegal abortions and go to the places where illegal drugs are sold to purchase abortion pills, many cut with fentanyl, in doses that are not recommended,” says Puerto Rican feminist activist Alondra Hernández Quiñones.

As religious and conservative groups gain traction in Puerto Rico, Dr. Vale worries that a girl of 15, whose parents are ultra-conservative and refuse to consent to her abortion (as the new legislation would require), would be forced into motherhood. Clinics like Darlington have stopped seeing patients younger than 15 at all, and Dr. Vale fears a future where abortion, currently a safe and regulated procedure, “will once again be a public health problem…where we don't know how many women end up in emergency rooms due to an [unregulated] abortion gone wrong.”

“This worries me a lot,” says Isharedmie Vazquez, a 17-year-old Puerto Rican student. “It seems incredibly wild to me that instead of guaranteeing secure options [for an abortion], what they are looking for is to criminalize it and force women to assume a responsibility for which they are not prepared. It's unfair that they want to take away the right to decide about our lives.”

Susanne Ramírez de Arellano is an author on race and diversity, opinion writer, and cultural critic. The former news director of Univision, she writes for NBC News Think, Latino Rebels, and Nuestros Stories, among other outlets.

Susanne Ramírez de Arellano is an author on race and diversity, opinion writer, and cultural critic. The former news director of Univision, she writes for NBC News Think, Latino Rebels, and Nuestros Stories, among other outlets.

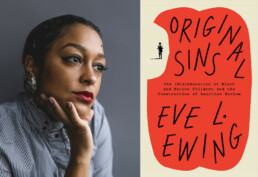

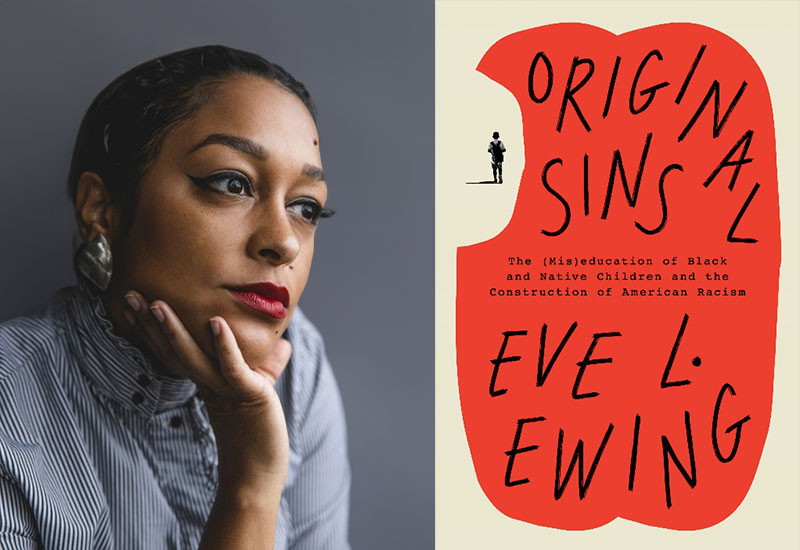

The “Recurring Lies” We Learn in School

As our country marks Black History Month by banning books about race from classrooms, writer Eve L. Ewing looks at the long, complex “miseducation” of Black and Native children.

BY REBECCA CARROLL

AUTHOR EVE L. EWING WANTS YOUNG PEOPLE TO “UNDERSTAND THEIR OWN RADICAL POWER."

It’s been less than a month of the second Trump administration, and already in its crosshairs is the Department of Education. Trump has pledged to abolish it, issued an executive order threatening to defund schools engaging in discussions around race and oppression, and has empowered Elon Musk, a white male billionaire who grew up under the racist apartheid system of South Africa, to cancel $900 million in research grants. If there is a next level of “hope,” we need it now—and no one embodies hope, especially when it comes to education, more than poet and scholar Eve L. Ewing. Her new book, Original Sins: The (Mis)education of Black and Native Children and the Construction of American Racism, approaches the issue of disparity in education—specifically for Black and Native students—with the revelatory question of, “What if American schools are doing exactly what they are built to do?”

From the earliest efforts to offer schooling to formerly enslaved Black people—efforts that were met consistently with questions of whether or not Black people were human enough to be educated—to the compulsory boarding school attendance of Native children with the aim of “civilizing” them, Original Sins unearths the DNA of America’s education system, and lays bare the ways in which our knowledge has “been impacted, and to some degree, severed by colonialism.” And as Trump cuts DEI initiatives in American universities and colleges, one note from the book resonates: Schools, Ewing writes, “have never been for us.” But, she continues, regarding the education system as a whole, “The good news is that people made it, and people can unmake it—and make new things.”

Rebecca Carroll: It seems that from the start, the educational attitude toward Black folks was: We’ll give you subpar resources, but will (mostly) leave you alone as long as you stay away from us (white folks). While for Native Americans, it was: We’re going to steal your children, and destroy all their cultural ties to you. Why were the educational strategies used against Black folks and Native Americans so different from one another? Or were they?

Eve L. Ewing: The United States was founded on land that was violently stolen from the Native people who had lived here since time immemorial, and that land was tilled by enslaved Africans who were stolen from their homelands, degraded, and treated as property. Those foundational thefts enriched the nation at the expense of the lives, land, and dignity of Black and Indigenous peoples. And those actions didn’t happen in one discrete moment—they continue to reverberate in the world we live in today.

So in order for the country to sustain itself, it has required an intellectual underpinning that justifies those evils. It requires a set of recurring lies, to make it all seem okay. And that’s where schools come in: a place to make the lies seem real. Three of those lies that I talk about in the book are: the lie that Black people and Native people are intellectually inferior, the lie that our bodies and our children’s bodies inherently require more discipline and control, and the lie that we are destined for economic subjugation, that it’s our fate in life to lie at the bottom of a capitalist hierarchy.

There are ways that anti-blackness and anti-indigeneity use the same weapons, but there are indeed ways that the strategies diverge. And the reason for that is that white supremacy has historically needed different things from us. It has needed Black people to be subservient, and it has needed Native people to be gone. That’s how I would put it simply.

RC: What do you think is the responsibility of educators who began their careers when the official default was white supremacy? Is there a process of undoing (not a punishment) that needs to occur for teachers of all races who, for perhaps decades, taught children of all races through the lens of racial hierarchy?

ELE: It’s a hard question. I think it’s important to begin by centering ourselves in relationships. All of us—in our personal lives, in our work lives—have had moments when we thought we were doing our best, and it’s made clear to us that the people we loved were not served by our choices. When that happens, we have a choice to make: Do we choose to be defensive, or do we take the opportunity to be reflective? If someone takes the time to try to teach you to do better, to be better, that’s an act of love. Are you able to receive that love, or not? Are you able to be accountable for your actions? That’s a question for folks to ask themselves. At the same time, we need to be making space for people who are radically caring and transformative to enter the profession.

RC: Speaking of undoing racist teachings, you cite the work of scholars Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, who disparage the “easy use” of the word “decolonize.” They note that in recent years, social justice activists have suggested “decolonizing” certain spaces and ideology…but in doing so have actually trivialized the word. Is it not possible, though, for an easy use of a term to also be effective?

ELE: I think the question has to be, effective for what? …Real decolonization is not easy, and if a violent colonial institution continues to profit from harms against Indigenous peoples, having a single book or training or workshop or affinity group and then saying that that is “decolonizing” could be not only misleading—it could be actively dangerous, because it gives people a facile representation of what decolonization is. It reminds me of a moment in 2020 when the university where I work declared that they were committed to anti-racism, which could not have been further from the truth. So I see it as less of a scholarly conversation, and more of a “say it with your chest” conversation, or a “don’t just talk about it, be about it” conversation.

RC: In a recent piece for In These Times, you wrote: “It’s not enough to be afraid of the laws and rules we don’t want to see in schools.…Who are the young people you love most….What are the values you hold dear that you want desperately for them to understand, to inherit?” To your young beloveds, or simply to your readers, what are the values you hold dear that you want desperately for them to understand, and to inherit?

ELE: Thank you for that question! I want the young people in my life to understand their own radical power to love: to love themselves, to love others, to love the lands and waters and more-than-human relatives, and to understand how strong we are collectively when we turn that love into action. I want them to voraciously seek out stories in all forms and to see themselves as storytellers. And I want them to understand Chicago history and the history of great Black artists who shaped culture as we know it.

A President-Free Newsletter

February 13, 2025 Dearest Meteor readers, Ahead of Presidents Day, we’ve decided to give you a break from all things presidential. (That means we won’t be covering the Linda McMahon confirmation hearings today or her terrifying education agenda, but don’t forget to call your senators.) Enjoy this reprieve while it lasts! Also, you heard it here first: Our annual Meet the Moment event is coming up on International Women’s Day, March 8! It’s a day of intergenerational conversations and performances with women and nonbinary people of all ages—past speakers include everyone from Jane Goodall to America Ferrera, so get ready!! And grab your tickets now. Today, we dig into some ‘70s feminist history, offer a bit of good news out of Kansas, and ask author Haley Mlotek three questions about divorce. Saging the space (for now), Nona Willis Aronowitz  WHAT'S GOING ONThree Marias, full of grace: Maria Teresa Horta, a Portuguese folk hero who helped spark a feminist movement in her country, died last week at the age of 87. She was the last surviving member of a trio known internationally as the Three Marias, who in 1972 published Novas Cartas Portuguesas (New Portuguese Letters). The book was a ragtag compendium that told the story of women’s oppression under dictatorship in Portugal. Their backstory: In 1971, Horta, Maria Isabel Barreno, and Maria Velho da Costa—all well-established writers in their thirties—started meeting weekly for consciousness-raising sessions and bringing notes, fantasies, and letters to one another. Apparently inspired by the 17th century classic “Letters of a Portuguese Nun,” these dispatches discussed everything from rape and domestic violence to abortion and forbidden orgasms. The three women eventually published a collection of these musings, vowing never to reveal which of them had written each fragment.  AN EXTREMELY DOPE MURAL OF THE THREE MARIAS BY ELTON HIPOLITO IN VILA NOVA DE CERVEIRA, PORTUGAL It was a juicy, racy, defiant text that flew in the face of everything Prime Minister’s Marcelo Caetano’s authoritarian regime stood for. It was also a direct challenge to the censors, who had recently banned one of Horta’s volumes of poetry. “Let us put an end to mystifications and false modesty, let us cleave from top to bottom the waters we are drowning in without being able to draw a single breath,” they wrote. “Hasn’t the time come to share with each other, for example, the truths we know about our pleasures in bed?” They weren’t kidding: Throughout, there was straight-up erotica, about “tumescent fruit” and “silk buttocks” and “fingernails scraping your skin.” As expected, the book was banned—but not before it had become an overnight sensation and sold out almost every copy. The Three Marias were swiftly arrested and imprisoned, charged with "abuse of the freedom of the press" and "outrage to public decency.” Caetano declared them three women "who aren't worthy of being Portuguese." The dustup, of course, helped them become internationally famous, garnering the support of icons like Simone de Beauvoir and Adrienne Rich. They were eventually acquitted in 1974 on the heels of the dictatorship’s demise. The Three Marias’ legacies are a reminder that desire for sex and liberation can pierce through even the most repressive governments. Looking back in 2014, Horta recalled that their meetings were her oxygen during an extremely dark time. It “was the most interesting thing of my life,” she said. “It is a book that grabs you because it is a book of political struggle.” AND:

KANSAS GOV. LAURA KELLY MEANS BUSINESS. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

Three Questions About…DivorceAuthor Haley Mlotek’s new book is a tender meditation on the transformative nature of dissolution. The “divorce narrative” has dominated lately, from Leslie Jamison’s Splinters to Lyz Lenz’s This American Ex-Wife to Miranda July’s All Fours, all of which focus primarily on the author’s individual liberation. But writer Haley Mlotek’s new book, No Fault: A Memoir of Romance and Divorce, stands out because it situates her personal story within the complex, painful and sometimes beautiful social history of divorce. Mlotek—a divorced writer with divorced parents, one of whom is a certified divorce mediator—excavates how the dissolution of marriage shaped the last century, and all the unique little heartbreaks and triumphs each divorce leaves in its wake. I spoke with her about divorce’s gravity, its role in this political moment, and how it intertwines with romance. Nona Willis Aronowitz: For me, being divorced is a badge of honor; it was proof I actually did something about my unhappiness. In the last pages of your book, you also admit to feeling kind of attached to your divorced status. In what ways do you think your divorce has shaped you and your desires? Haley Mlotek: There was a slight and almost morbid comedy to saying that I was divorced in the immediate aftermath — I had been married so briefly…and among my friends I was certainly one of the youngest people anyone knew who was going through a divorce. It was easy to turn this moment from my recent past into a joke, or a fun fact, or an easy anecdote in those days. Later, as more people in my life experienced some of the same things I had in my breakup and divorce, I thought more deeply about what that status actually meant to my present moment and my future. There’s a gravity to the status that’s not so easily explained, which I think has actually served me well — rather than relying on easy answers or quips, I had to think carefully about what I actually wanted to share, and most of that was some variation of …"I don't know, and maybe I never will." NWA: Besides your personal story, you lay out the fascinating history of divorce itself, and by extension, marriage—including how both intertwined with feminist movements. What role do you think divorce plays (or should play) in discussions of gender and feminism during this regressive political moment? HM: Historically, [marriage and divorce] have always been an arena that fascists have turned to to exert control over people, and as we see every day, neo-conservative and neo-liberal politicians alike are also quick to use their own ideals of the family to their own political ends. The book Family Values by Melinda Cooper is an excellent study of this, as is Making Marriage Work by Kristen Celello. More than that, this threat of the extreme right turn across the world is an emergency reminder that no struggle is separate from another — the attacks on trans people, undocumented people, and the families of Gaza and Palestine are all part of the same destructive agenda that seeks to dehumanize anyone that stands in the way of a cancerous spread of power. As many of the people I cite in my book note, the family and the couple are the smallest political unit that most people are a part of, which makes it an essential part of how we show up to protect ourselves and our loved ones. The ability to choose how we build our relationships and who we build them with is not limited to marriage, nor is the decision to leave those partnerships limited to divorce, but it is a part of a structure that can build support in the fight against the current regressive political moment and its future implications. NWA: Obligatory Valentine's Day question: What is the most romantic thing about divorce—or is it, by its nature, just inherently anti-romantic? HM: The concept that marriage is something that can be tried more than once suggests a belief that nothing matters more than the pursuit of love. There’s also the fact that romance needs a little bit of tragedy to give it that sense of risk and gravity; the feeling that it can be lost or left is, to me, quite romantic. But that says more about me than it does about Valentine’s Day.  WEEKEND READING📚On enablers: The corporate owner of more than a dozen dating apps has known for years about abusive and violent users on its platforms—but, a new investigation charges, it has been loath to take action or inform users. On principles: Behind New York City mayor Eric Adams’ corruption case was Danielle Sassoon, a deeply conservative and ambitious prosecutor who resigned today in protest. (New York Times) On cannibal teens: Yellowjackets is back, baby! In honor of the Season Three premiere tomorrow, kindly enjoy this profile of Sophie Thatcher, who plays the show’s inimitable goth, Natalie. (The Cut)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()