On turning women’s pain into entertainment

By Tracy Clark-Flory

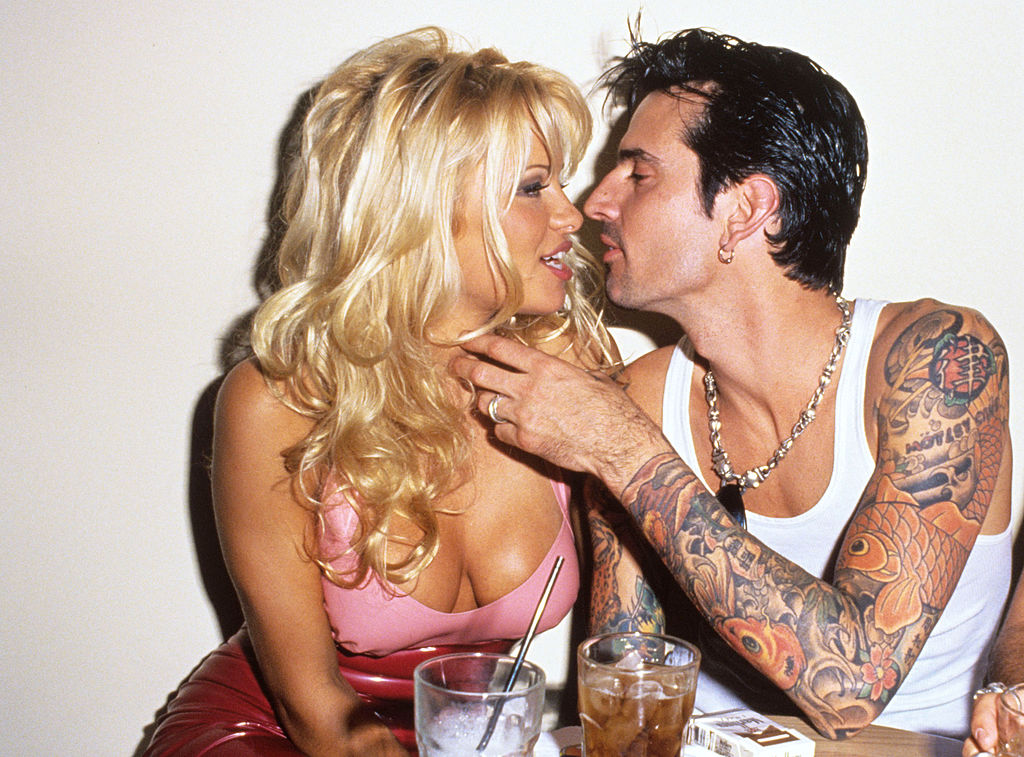

This week brought the finale of Hulu’s Pam & Tommy, a limited-series dramedy about the leak of a private sex tape that none of us should know anything about. We’re talking eight whole episodes reenacting the ’90s-era theft and viral spread of an explicit home movie starring celebrities Pamela Anderson and Tommy Lee. That’s more than five hours of television devoted to replaying a privacy violation.

The tape’s leak in 1995 was paradigm-shifting and emblematic of a cultural moment, so it’s possible to imagine a worthwhile critical retrospective. Instead, Pam & Tommy is less a reconsideration of the leak than a nostalgic reliving of it. It’s less about the tape than of the tape, which ushered in an ongoing era of stolen moments treated as entertainment.

Anderson and Lee’s video was historic as the first celebrity sex tape, spawning dozens of direct imitations, but also setting the stage for whole new privacy violations, like the 2014 hack targeting famous women’s nudes (a.k.a “The Fappening”). The tape’s leak teed up an explosion of nonconsensual entertainment online—and not just starring celebrities. Soon, everyday women had to reckon with the public humiliation of everything from “upskirting” videos to “revenge porn.” Fast forward over two decades and the majority of states have had to legally address nonconsensual pornography (or nonconsensual image abuse, as some experts now call it). The next challenging legal frontier: “deepfake porn”, where a person’s face is seamlessly swapped onto pornographic material.

But let’s be clear: leaked sex tapes aren’t really about sex. The most famous ones—as with Paris Hilton and Kim Kardashian—are defined by entitlement, trespass, violation, and embarrassment, vis-à-vis a woman. This is a fundamental part of the attraction: these videos provide forbidden access. Kevin Blatt, a self-described celebrity sex tape broker, says the appeal is seeing something you “weren’t supposed to see.” Even when there are questions about a sex tape being leaked for fame and publicity, there’s still the suspension of disbelief that allows viewers the fantasy of crossing boundaries, of getting what is not freely given. The entire meaning of the tape changes if a woman intentionally and openly participates in its creation and release.

We’re living in a cultural moment of re-evaluation around the sexism of the ‘90s and ‘00s, which no doubt helped greenlight Pam & Tommy, but the show’s true impulse is to laugh and wax nostalgic

Pam & Tommy itself adds another layer of non-consent to the original violation of the tape’s leak: Anderson wanted nothing to do with the series. (While Lee has voiced support for Pam and Tommy, Anderson reportedly finds its release “very painful.”) The show was made anyway—and then promoted as “feminist” for being sympathetic to her experience.

In reality, the show identifies at the start with Rand Gauthier (Seth Rogen), the contractor who stole the tape after remodeling the couple’s mansion. We’re given a comedic, rollicking justification for the theft: Tommy Lee (Sebastian Stan) is an over-the-top asshole clad in a banana hammock who barks unreasonable orders at Rand. These early episodes are driven by laughs—take the scene where Tommy has a conversation with his own penis, which talks back via cringey animation.

We’re living in a cultural moment of re-evaluation around the sexism of the ‘90s and ‘00s, which no doubt helped greenlight Pam & Tommy, but the show’s true impulse is to laugh and wax nostalgic.

The series does eventually get around to inviting identification with Pam (Lily James), instead of literal and figurative dicks. It depicts Pam’s struggle to be taken seriously as an actor as her Baywatch lines are cut to prioritize zoomed-in shots of her butt. After the sex tape is leaked, Pam & Tommy spotlights her pain, portraying Pam as having a devastating miscarriage amid the stress of the violation.

In many of the moments of Pam’s emotional fallout, the show and the tape uncomfortably converge. Pam & Tommy feels like an unintentional meta-commentary on the many ways we are entitled to, and entertained by, women’s pain—not just with leaked sex tapes but also with limited-run TV series dramatizing leaked sex tapes.

Pam & Tommy is less a reconsideration of the leak than a nostalgic reliving of it. It’s less about the tape than of the tape, which ushered in an ongoing era of stolen moments treated as entertainment

Eventually, Anderson is shown in a brutal and shaming deposition for her lawsuit against Penthouse’s Bob Guccione, as she tries to stop the magazine from publishing stills from the tape. She is cross-examined about her sex life and even forced to watch parts of the tape in a room packed with men. We’re meant to feel outraged, but that outrage arrives after Pam & Tommy has already had its giddy fun.

The tone-deafness of the first half of the series is only matched by the inappropriateness of its handling of partner violence. Though it’s not depicted in the series, Lee was sentenced in 1998 to six months in jail for felony spousal abuse following an incident in which Anderson accused him of kicking her while she held her 7-week-old son; she had “a broken fingernail and red marks on her back,” according to police.

The series portrays several early red flags in the relationship—like Tommy calling Pam non-stop and following her uninvited on a trip to Mexico—but treats them as fun material. Pam & Tommy leaves Lee’s arrest, and their divorce, as a literal postscript at the end of the series. It’s a sanitized version of events, referring only to “a physical fight in the couple’s kitchen.” Hulu has cheekily promoted the show as “the greatest love story ever sold.”

All these years later, it’s tempting to believe that we have enough perspective to critically revisit this long-ago sex tape leak and other misogynies of yore. Instead, the last two decades have created a convenient new cover for exploitation: Pam & Tommy delights in replaying the violation, only to abruptly pivot toward superficial wokeness. It makes claims of a redemptive narrative while risking retraumatizing one of its subjects. Ultimately, the show is an accidental testament to the many ways women’s suffering is consumed as entertainment.

You can call it “reflection,” but we’re not nearly as far away from these events as we might like to think.

Tracy Clark-Flory is the author of the coming-of-age memoir Want Me: A Sex Writer’s Journey into the Heart of Desire (Penguin, 2021), a New York Times “notable” book and NPR best book of the year. For over 15 years, Clark-Flory has reported on feminism, gender, pop culture, and sex.

Tracy Clark-Flory is the author of the coming-of-age memoir Want Me: A Sex Writer’s Journey into the Heart of Desire (Penguin, 2021), a New York Times “notable” book and NPR best book of the year. For over 15 years, Clark-Flory has reported on feminism, gender, pop culture, and sex.