Puerto Rico's Dimming Future

|

Hola, Meteor readers, Anyone else feel like time is moving at lightning speed and a snail’s pace all at the same time? Anyone? Just me? We are somehow approaching the end of this year, which I could have sworn just started three weeks ago. Either I've discovered time travel or Thanos has re-acquired the infinity stones again. Who knows! In today’s newsletter: a disastrous contract extension in Puerto Rico, positive news out of Jackson, Mississippi, and a little time spent with the Harry and Meghan trailer. Screaming “HOW IS IT DECEMBER?!”, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONSe fue la luz: After Puerto Rico was devastated by Hurricane Fiona in September, we wrote about Luma, the private power distributor behind the crumbling energy grid leaving thousands of islanders without electricity. And now, despite massive outcries from the public, the board of Puerto Rico’s Electric Power Authority (PREPA) has chosen to extend Luma’s private contract with the island, giving the company control of the power system for an indefinite amount of time. According to AP, “Luma’s contract is expected to remain in place until the bankruptcy of Puerto Rico’s power company, which holds some $9 billion in debt, is resolved.” What does this mean for all the American citizens living in Puerto Rico with no or unreliable access to electricity? I’ll put it as frankly as I possibly can: The PREPA board and Governor Pedro Pierluisi basically looked Puerto Ricans right in the eye and said, “Se pueden joder,” which loosely translates to they can go fuck themselves. During a news conference, Pierluisi said “canceling the contract makes no sense right now” due to how much it would cost to do so. And yet maintaining the contract, which ensures a payment of over $100 million to Luma, is the sensible option? There needs to be a plan C. For an in-depth and comprehensive explanation of what’s happening and how it’s affecting citizens, consider watching the latest report on the power outages from independent reporter Bianca Graulau: AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays. Ideas? Feedback? Requests? Tell us what you think at [email protected]

|

![]()

Inside China's Historic Protests

NEWSLETTER

November 29, 2022

Hey there, Meteor readers,

Did ya miss us? We missed you! We hope that you and yours had a pleasant Thanksgiving/Native American Heritage Day/Black Friday/Small Business Saturday/Cyber Monday and that your credit card statements do not runneth over. I, for one, spent [REDACTED] dollars on yarn/knitting patterns over the weekend and will be eating wool until the next fiscal quarter. (Worth it.)

In today’s newsletter, we’ve got a breakdown of what’s happening in China, plus a quick tour around the World (Cup). Let’s get into it!

Squishing yarn balls,

Shannon Melero

WHAT’S GOING ON

The People’s Republic: This week, images of protests in China have flooded the internet as citizens take a stand against their government’s “zero COVID” policy. The policy aims to bring the number of COVID cases as close to zero as possible by implementing what some feel are extreme measures, especially in contrast to the rest of the world. China has closed its borders to tourists, forced citizens reentering the country to quarantine, and sent government drones with loudspeakers circling overhead, reminding folks to wear masks or stay indoors. While this policy kept deaths down during the start of the pandemic, it also made it more difficult for those who have never been exposed to the virus to build any sort of immunity to the Omicron variant now hitting the country. Non-COVID deaths have also spiked in the country, since the strict lockdowns prevent citizens from receiving prompt emergency medical care.

So why protests now? They began last week after 10 people died by fire in an apartment building where strict lockdown measures were in place. (In response, government officials said those who died were simply “too weak” to escape the flames.) But what started out as a protest about a fire in a heavily surveilled area of China quickly evolved into what the Washington Post calls “a larger rebuke of China’s zero COVID policies, government restrictions and surveillance, and, in some cases, explicit criticism of Chinese leader Xi Jinping.”

These incredibly creative protests are unlike any we’ve seen in China in decades. Due to censorship laws, Chinese citizens cannot simply walk into the street and speak out against their government. To get around this, some are using blank sheets of paper which represent “everything we want to say but cannot say,” a protestor told Reuters. One group of university students opted to use a specific physics formula—the Friedmann equation—as their protest sign. As activist Nathan Law explained on Twitter, “It’s the pronunciation: it’s similar to “free的man” (free man)—a spectacular and creative way to express, with intelligence.” Other Twitter users familiar with the equation, which calculates the expansion of the universe, view it as a demand to reopen the country. Meanwhile, the BBC reports that Chinese officials are actively seeking out citizens who they believe attended protests over the weekend, even though “it is unclear how police might have discovered their identities.”

AND:

- In just a few days, SCOTUS is set to hear a case that has been described by former Attorney General Eric Holder as “an existential threat to our democracy.” The Atlantic breaks down everything we need to know about Moore v. Harper.

- An investigation by The Times and Sunday Times has found “slave-like” conditions for workers at fashion retailer Boohoo.

- The expanded child tax credit ended last year; newly released figures show that child poverty rates have gone back up, leaving millions of families facing food insecurity.

- Early voting for the Senate run-off race between Herschel Walker and Rev. Raphael Warnock in Georgia began on Monday and over 239,000 votes were cast–a new record for single-day votes collected in the state. This is the only time I’ll ever be happy to see ridiculously long lines. Keep voting, Georgia! We’re all rooting for you.

- And over in Alaska, Mary Peltola, of Yup’ik descent, became her state’s first Native member of the house bringing the total of women U.S. Representatives to a record 124.

AROUND THE WORLD (CUP) IN 60 SECONDS

If there’s one thing the 2022 World Cup is proving, it’s the power of sports. Who knew a couple of guys kicking a ball around would be one of the year’s most gripping global political events? Since the complex and layered stories coming out of Qatar would take days to dissect on our own, we’re saving everyone a little time by giving you all the top beats of the week in one quick hit. Clock starts now!

- Several players have been falling ill because of the air conditioning in the newly (and controversially) built stadiums around Qatar.

- A fan who ran onto the pitch carrying a rainbow flag has been released from police custody and is now banned from attending any more games. (For non-soccer watchers: Even without the pride flag, which has been a contested issue in Qatar, it is illegal and incredibly dangerous for fans to run on the pitch at any soccer venue.)

- Iranian women attending World Cup matches in person are sharing their fear that government “spotters” are watching their every move while in Qatar.

- Three Iranian protestors who were detained after a match for wearing “Women Life Freedom” t-shirts are speaking out about the experience.

- At a press conference ahead of the USA vs. Iran match today, an Iranian journalist gave United States Men’s Team captain Tyler Adams all the smoke by first telling him very firmly how to pronounce Iran and then asking him how he felt about representing a racist country after telling him very firmly how to pronounce Iran. (The ask has been widely criticized, but honestly, it was a fair question!) On the flip side, the Iranian head coach Carlos Queiroz also had to face tough political questions during his press conference, which he handled with as much grace as he could given that he knows his government is watching him. Team USA went on to win the match 1-0, with the only goal of the game being scored by Christian Pulisic. Despite the loss, Iran’s performance on offense was something to be proud of, and had they matched that energy on defense, Team USA would be on a flight back home right now. But that’s the pain and glory of the beautiful game.

The Rhetoric That Led to the Club Q Violence

NEWSLETTER

November 22, 2022

Greetings, Meteor readers,

We are in the midst of that very weird week at the end of November where there’s too much to do and not enough time to get it done. Folks are traveling, seasoning their birds, decorating their homes, or mentally preparing for the obligatory interaction with that one uncle you’re almost certain was there on January 6th even though you can’t quite prove it. Or perhaps you’re doing none of this and simply reflecting on the real history of this holiday. (If that’s you, here’s some extended listening to get you through the week.)

Wherever you fall on the Thanksgiving celebration spectrum, we just want to say we’re grateful for each minute you’ve spent with us in your inbox. The greatest gift is community, and we’re honored to have you in ours.

In today’s newsletter, we mourn the loss of five lives in the Colorado Springs shooting and catch up on a few other things going on in the world.

Writing from the land owned by the Lenni Lenape,

Shannon Melero

WHAT’S GOING ON

Grieving Club Q: The country is still reeling from the shooting in Colorado Springs, where a gunman opened fire inside an LGBTQ+ nightclub, killing five and injuring 18. The victims have been identified as Raymond Green Vance, Kelly Loving, Daniel Aston, Derrick Rump, and Ashley Paugh. This tragedy shines an ugly spotlight on the many ways our culture says “never again” after each horrific incident while continuing to act in ways that ensure that there will be another.

Like many queer gathering spots, Club Q was described as a haven for the community—and an especially necessary one after a year of anti-trans legislation, harmful queer-phobic rhetoric from politicians, and a targeted attack on drag shows by the right wing. (In 2022 alone, according to the Counting Crowds Consortium, there were more than 40 right-wing actions targeting drag shows and Drag Queen Story Hours—like the brunch Club Q was planning for the day after the shooting occurred.) Now the same politicians who so adamantly charged their constituents to rally against drag queens, transgender people, and LGBTQ+ folks in general are now sending thoughts and prayers to those affected by the shooting.

And then there’s the second issue at hand: inadequate gun laws. Colorado’s “red flag” laws require civilians to report incidents of violence involving gun owners so that a red flag can be triggered and their firearms can potentially be seized. But this case shows those laws are of little use. Last June, Anderson Aldrich, the suspected Club Q shooter, was arrested for issuing a bomb threat—but because he was not charged, and no one who knew Aldrich filed a report, he was allowed to keep (and allegedly use) his firearm. Colorado State Rep Tom Sullivan told AP, “We need heroes beforehand—parents, co-workers, friends who are seeing someone go down this path.” But we need politicians to be heroes here and pass stronger gun laws. The firearms used at Club Q (one of which was an AR-style weapon) were legally purchased by a man who had already proven himself capable of violence; this is not a problem we should be turning to good Samaritan citizens to solve.

AND:

- Election denier and Arizona gubernatorial election loser Kari Lake has suddenly become very concerned about voter suppression. The extremely convenient tonal shift comes amid (debunked) GOP claims that voting machines used at the polls were not up to code. The situation has become so dire that some election officials have actually gone into hiding after receiving death threats.

- Even if you’re not watching, it’s nearly impossible to get away from all the goings-on at the World Cup in Qatar. One of the few positives coming out of the tournaments (other than Messi being humbled by Saudi Arabia in a historic upset) is the act of solidarity from the Iranian national team, who refused to sing their country’s national anthem during their opening match. One fan told Reuters, “All of us are sad because our people are being killed in Iran, but all of us are proud of our team because they did not sing the national anthem—because it’s not our national (anthem), it’s only for the regime.”

- GATHER ROUND, ELDER DISNEY MILLENNIALS! I HAVE NEWS! Brandy, one of the best ever to play Cinderella on screen, will be reprising her iconic role in Disney’s next installment of its Descendants film franchise. Make sure your pitch pipes are ready; rehearsals for the “Impossible” sing-a-long begin at dawn.

IN CASE YOU GET LONELY

Normally we’d see you again on Thursday but The Meteor will be closed until next Tuesday. So just in case you miss us, here are a few pieces from our archive to get you through the long days.

For anyone who has to figure out where they’re going to college: I Asked 61 Colleges If They Would Pay for Students to Travel for an Abortion. Only Five Hinted That They Might. by Talia Kantor Lieber

If you need a reminder on the importance of shopping small: The Unsung Heroes of the Labor Movement by Esther Wang

For anyone using their downtime to binge The Crown: Princess Diana’s Death Is Personal for Me by Susanne Ramírez De Arellano

To keep up with your friends who read a lot: Why “Men are Trash” Is Not Enough by Samhita Mukhopadhyay

Looking to relax your mind? Try: The Radical Act of Rest from UNDISTRACTED with Brittany Packnett Cunningham and guest Tricia Hersey or The Key to *Actually* Unplugging by Megan Reynolds

To support more LGBTQ+ stories: The Transgender Tripping Point by Jennifer Finney Boylan and How to Celebrate Pride in the Middle of Anti-Trans Backlash by Phillip Picardi and Raquel Willis

Pelosi's 20 long years

|

Dear Meteor readers, Last Saturday, we gathered together for Meet the Moment. It was such a privilege to share space with leaders in the worlds of reproductive care, climate change, the Iranian feminist movement—and many of you! Plus music, art, and even some comedy. I had tingles all over my body when Tarana Burke took to the stage to discuss survivorhood with her child Kaia Naadira, actor Anthony Rapp, writer Chanel Miller and moderator Dr. Salamishah Tillet. “We don’t heal alone,” Burke  If you weren’t able to join us in Brooklyn, no worries! In today’s newsletter, we’re giving all the deets on one of my favorite talks of the day: a conversation with climate activists Thanu Yakupitiyage and Jamie Margolin. But first, this week’s news from my colleague Bailey Wayne Hundl. Let’s get into it. Eagerly meeting all the moments, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONEnd of an era: Nancy Pelosi has just announced that she will be stepping down from her role as Speaker of the House. Not only was she the first woman ever in the House’s highest-ranking and most powerful role, but she held that job for two whole decades—an era which, especially recently, has not been easy for visible political leaders. (Consider the recent assassination attempt on her husband: The attacker was yelling “Where is Nancy?”—just as the January 6 insurrectionists did when they chanted “Naaaancy, oh Naaaancy.”) As she passed the torch to the next generation today—including her likely successor, Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.)—she said, “I look forward to the unfolding story of our nation, a story of light and love, of patriotism and progress, of many becoming one. And always, an unfinished mission to make the dreams of today the reality of tomorrow.” “Don’t expect much of anything”: As you may recall, exactly nine days ago, young people went to the polls at near-record levels—many motivated by the recent death of Roe v. Wade. So you might be surprised to hear that when President Biden was asked Monday what Americans should expect Congress to do on abortion after the midterms, he responded: “I don’t think they can expect much of anything.” Inspiring, right? Biden’s point may have been that Republicans will soon take control of the House (which, unfortunately, was correct), but there are still things Congress can do—and should. As abortion rights activist Renee Bracey Sherman has pointed out, Democrats could still abolish the filibuster or reverse the Hyde Amendment, which prevents federal funds from being used for abortions. But it has to happen in the next two months before the anti-abortion party takes charge of the House. In other words: Stop saying there's nothing we can do, Joe, and let's do the things we can! Ticketmaster tanks: A moment of silence for the Swifties, please. On Tuesday, presale tickets for Taylor Swift’s Eras tour went live on More deaths in Iran: The violence against Iranian citizens protesting in the wake of Mahsa Amini’s death continues to escalate. On Wednesday evening at a protest in Izeh, seven people were killed by gunmen, including two children. The youngest was nine-year-old Kian Pirfalak, who was on his way home with his family at the time. State authorities have claimed this was a terrorist attack, but sources close to Pirfalak’s family claim the boy was targeted by Iranian security forces. This news comes on the heels of an increase in death sentences for detained protestors. AND:

MEET THE MOMENT We’re Already Living In the Climate DisasterBut this insight from climate activists is keeping me goingBY SHANNON MELERO  THANU YAKUPITIYAGE AND JAMIE MARGOLIN TALKING CLIMATE ON THE MEET THE MOMENT STAGE LAST WEEKEND. (IMAGE BY CRAIG BARRITT VIA GETTY IMAGES) Anyone who has interacted with me knows that I simply do not go to Brooklyn. (Sorry, BK readers; it’s not personal.) I am originally from the Bronx, so culturally (as well as MTA-illy) Brooklyn is on a different planet. But as I spent this last Saturday sitting in the Brooklyn Museum, listening while leaders and champions of gender justice bathed me in their knowledge, there was one moment in particular that made me say, “This is what I’ll be thinking about the entire ride home.” And sure enough, I spent the entire commute back thinking about Jamie Margolin, who spoke on the youth-led climate movement and where we are in our current crisis. “I’m not even gonna lie to y’all,” she said, “It’s already too late to stop climate disaster because it’s already here. People are already dying and it’s very insulting to people who have already lost everything to be like, ‘Someday, climate change is gonna happen.’” During the conversation, Margolin’s co-panelist Thanu Yakupitiyage asked her why we’re seeing such a significant youth presence in the climate movement. Why are activists like Greta Thunberg, Xiye Bastida, Margolin, and others the most visible climate advocates? Margolin responded with a view I’d never heard: It isn't just that younger generations have the most to lose as this disaster progresses; it’s that society (and media) are so obsessed with youth that the elders on the frontlines who started this movement simply get ignored. “The elders are standing right there with us,” but get pushed out of the frame, she says. And when they’re not ignored, they’re used as scapegoats for why the climate crisis is so bad in the first place. As an example, Margolin mentioned her grandmother, who doesn’t label herself a climate activist but taught Margolin everything she knows about caring for the land. This struck a deep chord with me personally, especially when Margolin called her grandmother a “campesina,” a phrase I’ve heard in my own household. (Depending on the dialect of Spanish you use, the literal translation can mean a few different things, but it generally refers to a woman who lives off of the land, or a farmer.) I am a descendant of a long line of sugarcane and tobacco farmers. My grandmother didn’t just have a green thumb; she had an entirely green upper body. She could bring back to life any plant in any condition. My family had a deep understanding of caring for the land long before I came to read about it on Instagram. And before I ever heard the word upcycle, my grandmother (maybe yours too?) was reusing old cookie and cracker tins as storage containers for anything and everything under the sun. Why buy brand new Tupperware when you can put leftover food in a cleaned out tub of Country Crock? The climate movement is in my blood and the blood of so many people of color—and we may not have even known it. JAMIE AND THANU BACK WHEN THEY WERE (EVEN) YOUNGER CLIMATE ACTIVISTS. (IMAGE COURTESY OF PANELISTS) I felt this buried connection sparked anew as Margolin spoke about our ancestors paving the way for the modern climate movement. It provided me with newfound awe and respect for them. How did we veer so far off the path of our elders, specifically those with indigenous roots and ties to the land, that we now find ourselves trying to put out a planet-wide fire with paper straws? Margolin’s answer: colonialism (which destroys native lands and land-caring traditions by eliminating entire cultures) and capitalism—two concepts that are at the forefront of my mind as we approach one of the largest food-waste holidays in America. It would be so easy to dip further into climate despair as we hurtle toward the end of the year, with its holiday waste, extreme weather, and climate-fueled immigration. But Jamie Margolin and Thanu Yakupitiyage don’t feel hopeless, and they shared that warrior energy with every person in the room. “Everyone thinks activism only means being out on the street protesting, but there are other ways to engage your community,” Margolin explained. She and Yakupitiyage delved into how we can use our own skills as individuals—whether we’re writers, artists, or office workers—to “target the big fish.” They also put an emphasis on the fact that there’s still time to turn our attention away from individual blame and direct it at corporations for their outsized role in filling the ocean with microplastics. There’s still time to quit fast fashion, to learn a little of what your grandparents might have known, to push your professional and personal communities to do more. There’s still time to vote for political leaders who believe in immigration policies that take into account climate refugees—and who don’t think shipping them away on a bus to the Vice President’s house is an appropriate response. While there is breath in our bodies, there’s still time to make sure the Generation Alpha isn’t spending their entire youth fighting the same fights as Gen Z. Confused on how to meet this particular climate moment? Let the youth point the way.

Shannon Melero is a Bronx-born writer on a mission to establish borough supremacy. She covers pop culture, religion, and sports as one of feminism's final frontiers.  PRESENTED BY FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Will More Iranian Protestors Face the Death Penalty?

|

Ba'ax ka wa'alik, Meteor readers, Why am I greeting you in Yucatec Maya, you ask? Well if you watched Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, you know the answer. I’m not going to give anything away, but I will tip my hat to all involved in bringing Namor and the people of Talokan to life with such artistry and reverence for Mesoamerican culture. Some superhero movies are just superhero movies, but this one truly felt like a celebration of cultures. Today, The Meteor crew is still recovering from our live summit Meet the Moment—which, thanks to our speakers, performers, and all of you who were there, was a wonderful day of conversation and healing. (More on that in Thursday’s newsletter, so be sure to stick around.) And by recovering, I mean my boss Samhita is gone and my coworkers and I are plotting rebellion:  So while Bailey and I whittle our pages down to a tight 45, we hope you enjoy a tour through this week’s news, including strange happenings at Amazon and an update on the important investigation into the killing of Shireen Abu Akleh. Ka ka’at, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONHunt for the truth: The United States has launched an official investigation into the killing of Palestinian American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh, who was shot in the head while wearing bulletproof press gear in the West Bank in May. Despite the Israeli Defense Forces initially denying involvement, the IDF admitted later that there was a “high possibility” that it had shot at Abu Akleh—yet the government failed to file any charges and instead offered lip service on “internal investigations.” But on Monday, the U.S. Department of Justice announced it would be launching an investigation into the killing. Israel vehemently refuses to cooperate, but this move from the DOJ is a long overdue reminder that journalists, including Palestinian ones, cannot be killed with abandon. Lives on the line: The Iranian government has sentenced a man to death after he was arrested for participating in anti-government protests in response to the death of Mahsa Amini, the young woman killed while in police custody in September. The protestor was found guilty of “enmity against God” after allegedly setting a government building on fire, the BBC reports. Meanwhile, hundreds of other protestors currently under arrest await their fate, and Iran Human Rights (IHRNGO) has found that at least 20 of them are facing charges punishable by death. Exactly how many protestors are at risk in Iran right now? Because of the Iranian government’s withheld or misleading information, it’s been hard for independent sources like IHRNGO to confirm exact numbers—but what we do know is that the average age of protestors being arrested is 15. And the Iranian government has already carried out two juvenile executions this year. AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Finally, Some Good News

|

Hey there, Meteor readers, Friends, new and old, I have a confession to make. My name is Shannon and I am a Zanab Defender. I have alienated my friends, my colleagues. I have been accused of being on the wrong side of history (dramatic). But I know I will be vindicated.  Now that we’ve gotten the hard part out of the way—and if you don’t watch Love is Blind, those last few lines meant nothing to you—we’ve got some updates for you on the midterms, and the news. Let’s get into it. Drinking Cole’s tears, Shannon Melero PS: Enter to win free tickets to our event this Saturday at the Brooklyn Museum. More details below but literally, you do not want to miss this. And did you hear me when I said F-R-E-E?  YEAH, WE'RE STILL THINKING ABOUT ELECTIONSThe good: So much good came out of these midterms—let’s really take a second to marinate in that. Gen Z turned out in record numbers in support of Democratic candidates and played a huge role in preventing the “red tsunami” so many analysts feared. Good job, kids! Speaking of the youngs, Maxwell Frost is now the first Afro-Cuban Gen Z’er member of Congress representing Florida. (By the way, he’ll be joining us for Meet the Moment in Brooklyn this Saturday!) Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson defended her position against challenger Kristina Karamo. Wes Moore became the first Black governor of Maryland by a significant amount of votes. And in another first, Maura Healey of Massachusetts became the first open lesbian to be elected governor to any state in the U.S. And then there were the ballot initiatives: Kentucky, Vermont, Michigan, Montana, and California all voted to either enshrine abortion rights into their constitutions or otherwise protect it as a right for the citizens of their states. As Amanda Brown Lierman, executive director of Supermajority, told us last week, “That’s what gives me hope: the ability to think about abortion as a coalition-building issue, which is a new phenomenon for us.” THERE REALLY CAN BE MIRACLES WHEN WE BELIEVE. AND VOTE! The bad: Despite Frost’s historic win, Ron DeSantis easily won reelection as the governor of Florida, further setting him up as the golden child for the presidential election in 2024. Yuck. Another win causing unpleasant bodily reactions is that of Sarah Huckabee Sanders, who won the gubernatorial race in Arizona. Beto lost in Texas to sentient turd Greg Abbott. But perhaps the most devastating loss is the one that occurred in Georgia, where Stacey Abrams was unable to unseat Brian Kemp. We thank her for her unyielding service. The ugly: A lot of what happened Tuesday is too close to call, including the tense race between Raphael Warnock and Herschel “I may have paid for my girlfriend’s abortion but I’m antichoice” Walker, which will lead to a runoff in Georgia for a game-changing Senate seat. It would be one thing if this were a tight race between two qualified candidates, but…it’s very much not (and that’s the nicest way I can phrase it). That election is set for December 6, and don’t worry: We’ll be reminding you about it as frequently as possible because we love voting and hate poorly-equipped political representatives. Also, ICYMI, here in the year 2022 slavery was on the ballot in five states (Alabama, Oregon, Tennessee, Louisiana, and Vermont). Strangely enough, only four of these states voted to amend their constitutions to prohibit slavery and involuntary servitude carried out by imprisoned people. Louisiana will continue its long, long history of allowing slave labor.  AND:

JOIN US IN BROOKLYN THIS WEEKEND! Meet the Moment is upon us! This Saturday we’ll all be gathered at the Brooklyn Museum for a full day of events with some of the greatest thought leaders and voices of this generation and the next. PRESENTED BY  But the one voice we’d love to have in the room is yours. If you haven’t purchased a ticket yet, you can still win one free ticket for the entire day of talks, performances, and drinks by simply clicking the button below. Nothing else to do but cross your fingers and wait for the confirmation email that you’ve won. There are five tickets up for grabs and winners will be contacted Friday. See you at the museum!  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

We Want Politicians to Fear Women's Voting Power

November 7, 2022 ‘Twas the night before elections, and all through the House, every creature was stirring, even that guy that looks like a mouse. I could keep going, but I dropped out of my poetry elective in college for a reason. So let’s talk turkey, folks. Tomorrow is the big day. (Here at The Meteor, our offices will be closed.) So tonight, we’ve got some last-minute treats: an interview with Supermajority’s Amanda Brown Lierman on why women could literally change the outcome of tomorrow’s election—and voter guides to help you do it. Running out of rhymes, Shannon Melero  WHAT TO KNOWWho’s who: Still unsure who to choose in your state’s local election? This handy tool from Vote411 allows you to select your state and search for candidates, ballot measures, eligibility requirements, polling place locators, campaign finance information, and more. If this is your first time voting, PLEASE check eligibility requirements before going to your polling place. Some states are extremely specific about acceptable forms of ID (yes, it’s a strategy) and you don’t want to get turned away. (If you do, though, STAY in line and call the Election Protection Hotline.) Voting the issues: So you know who you’re voting for—but are you certain about what you’re voting for? Voting for the first Democrat you see on the ballot by default may have worked in the past, but with so many of our rights on the line, it’s time to read the fine print. Here are some guides curated by groups we know and trust:

FROM THE EXPERT“Our Oppressors Win When We Divide Ourselves”Amanda Brown Lierman talks to us about creating the most powerful voting bloc possible.BY SAMHITA MUKHOPADHYAY  LOOK HOW HAPPY WE COULD ALL BE IF WE VOTED! (IMAGE BY JEMAL COUNTESS VIA GETTY IMAGES) You already know you have to vote (and we trust that you will.) But how much difference will your vote make? And what is likely to happen tomorrow? For a view from the front lines, I turned to the executive director of Supermajority (an organization working to build national political power for women), Amanda Brown Lierman. Amanda has been working in the voting rights space for years: she used to work at Rock the Vote and was the organizing director at the Democratic National Committee. We’re also good friends and former colleagues. I wanted to hear from her what exactly is at stake tomorrow…and what’s giving her hope. Samhita Mukhopadhyay: How are you feeling about the midterms right now? Amanda Brown Lierman: I feel like the only thing I can do is hold hope. It is just amazing to see the commitment of women [at Supermajority] who are freaking tired and have every reason to be too tired to do this work. But they're showing up and they're showing out when it really does matter. Of course, I feel anxious because there's also so much at stake and so much on the line. Usually at this point in an election cycle, you spend a lot of time talking about why it's so important to vote for somebody. And there are incredible pro-women champions and pro-women leaders who are running for office. But there are also names on that ballot of people who don't deserve to be sitting in those seats of power. And in many cases, they are power-hungry white men who are not serving women, not serving the people who put them in office, and they need to be kicked out of those seats. Can you spell out a little bit what’s at stake? The president has made a couple promises about what he can and will do if we get him two more Democratic senators [giving Democrats a majority irrelevant of how Sens. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Joe Manchin of West Virginia vote]. And there are some really incredible women who are running for Senate. If we could deliver those two new Democratic senators, then we can actually make progress in some of those national policy conversations around childcare access, around paid leave, and other care economy issues that were cut out of Build Back Better. We could codify Roe at the national level. The gubernatorial races are going to be very important too. Gretchen Whitmer has been the number-one defender of women's rights in Michigan since she was elected in 2018. There’s also that ballot initiative in Michigan which intends to enshrine abortion as a constitutional right in the state. In Michigan—this is actually incredible, Samhita—in order to get an initiative on the ballot, you have to have something like 400,000 signatures. And they had 750,000 signatures for this ballot initiative in Michigan—double what was necessary, double what people thought was impossible to get done.  PROTESTORS IN DETROIT, MICHIGAN SHOWING UP AND SHOWING OUT FOR ABORTION RIGHTS. (IMAGE BY MATTHEW HATCHER VIA GETTY IMAGES) We saw something similar in Kansas in August, where voters voted to protect abortion rights. What are you seeing in the post-Roe political landscape? For so long, people have run away from having conversations about abortion, and abortion [historically] has been more of a polarizing issue than it has been a mobilizing issue. And what I think we're seeing in this landscape is abortion right now is not polarizing. It's actually created the opportunity for us to build coalitions in a way that we have never done before. And Kansas is such a great example of that. You have folks in Kansas, women in particular, who voted no on that amendment to make sure that we did not advance abortion bans in that state. Organizing is all about having conversations. It's all about connecting with somebody over a shared set of values. Women might not [all] have the same experience; they might not be motivated by the same issue. But I feel like we have been able to build connections, build coalitions around this value that our bodies should be respected and that women should be able to make a decision about their bodies—instead of power-hungry men who are sitting in a political seat. That's what gives me hope: the ability to think about abortion as a coalition-building issue, which is a new phenomenon for us. Oh, I love that. We want to make sure that women recognize their power as individuals, as voters, but also claim the power that we have as a collective. And our coalition, hopefully, is a voting bloc that is respected, is revered, and is... also, if I'm being honest, a little bit feared. I want politicians to be afraid of a whole lot of women voting because they have to be accountable to the very people that put them in office. Our oppressors win when the walls go up, and we divide ourselves. There are some signs that there could be record turnout. I voted in upstate New York, and it was a 45-minute wait to vote a week before Election Day. Wow. But the fact that the Zeldin/Hochul race feels so close in New York is not a great sign to me. I know you've worked in the voter space for a long time. What can we actually expect tomorrow? I think that there are people (notably Democrats) who have been dismissing this election for the last year with a sort of despair and just [resigning] to loss. So I do refuse to sort of give into that, and think it is our job to make sure that we do the work because change happens with one conversation, one voter. And that commitment to organizing, I think, is the only thing that has always worked, and has always saved us. But to your point: These elections are fucking close. And I think many of them will come down to field margins. And there's a reason why we have to give it our all, because some of these elections will be won or lost by two votes, by a hundred votes. And so this idea of giving in just makes me sick to my stomach and so angry. Because literally, if we each spent the time talking to—I mean, honestly, two to three people in the next couple of days and got them to the polls, it wouldn't be close. I think voting is an expression, and Election Day will be an expression of the collective as women flexing our political muscle and making sure that our voices are heard and demanding that of our elected leaders. I've been saying this a lot: They can ignore our primal screams, but they cannot ignore our votes.  PHOTO BY HEATHER HAZZAN Samhita Mukhopadhyay is a writer, editor, and speaker. She is the former Executive Editor of Teen Vogue and is the co-editor of Nasty Women: Feminism, Resistance and Revolution in Trump’s America and the author of Outdated: Why Dating is Ruining Your Love Life, and the forthcoming book, The Myth of Making It.  THANK A POLL WORKERToday is Election Hero Day, a day to recognize and thank all the folks who make it possible for us to show up and cast our votes. That includes your state directors, local clerks, staff, and (everyone’s favorite) the volunteers that hand out the “I Voted!” stickers. And they need support: They’re short-staffed, and too often under attack. Spread the love by sharing the image below from @electionheroday or kick it old school and thank an election worker face-to-face. (But keep a respectable distance; we are still in a pandemic.) (SCREEN SHOT VIA INSTAGRAM) Remember, Election Day is a marathon, so drink water, be patient, be kind—and above all, be there! We’ll see you on the other side.  Speaking of marathons, did you run the New York City Marathon this weekend? Let us hype you up! Send your marathon pics to [email protected] and we'll include them in a future newsletter. FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Stacey Abrams and Katie Hobbs On Running for Governor

|

Buona sera, Meteor readers, Before we get into anything, let’s address the elephant in the room. You know exactly what I’m talking about: Mariah Carey officially announced the start of the Christmas season on November 1 (which, for those lost in the space-time continuum, was two days ago). Can we please let November live!? We need to get through Thanksgiving, Mariah. Calm your reindeer. After all, we’ve still gotta get through Election Day. In today’s newsletter, we’ve got an exclusive interview with Stacey Abrams and Arizona Secretary of State Katie Hobbs, who are running for governor of Georgia and Arizona, respectively. Abrams is up against incumbent Republican Governor Brian Kemp, and Hobbs is in a heated showdown with Kari Lake, a Trump-endorsed election denier who recently said she wants a “carbon copy” of Texas’ abortion ban. The stakes are dire. But first, a little news—and some heroic doctors hanging out in DC. Not jingling any bells, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONRemembering Momen Zandkarimi: Unrest in Iran continues following the death of Mahsa Amini, who is believed to have been killed by Iranian security forces in September. The subsequent protests have led to the deaths of several other women, including Iranian TikToker Hadis Najafi, who was reportedly shot by Iranian police during a protest. And now Hengaw, a Kurdish human rights organization, reports that during a protest held in conjunction with Najafi’s mourning ceremony, another young person was killed. The victim, Momen Zandkarimi, was only 18 years old—and joins the at least 277 protesters whose deaths have been directly caused by Iran’s security forces this fall, according to Iran Human Rights (IHRNGO). Instead of seeking justice for the almost 300 lost lives, IHRNGO reports that the Iranian government has arrested dozens of protestors and charged them with “moharebeh (enmity against god) and efsad-fil-arz (corruption on earth) which [both] carry the death penalty.” IHRNGO believes the government will follow through on the death penalty in an effort to suppress further political uprising. AND:

DOCTORS FOR ABORTION ACCESS DAY OF ACTION AT THE U.S. CAPITOL. (PHOTO BY KISHA BARI)

THE 11TH HOUR INTERVIEWWith Five Days to Go, Two Women Running for Governor Talk to The MeteorStacey Abrams and Katie Hobbs on their historic runs: “It’s helpful to have someone who understands what you’re going through.” BY ASHLEY SPILLANE  THE HONORABLE STACEY ABRAMS. (IMAGE BY MEGAN VARNER VIA GETTY IMAGES) The people we elect on November 8 will decide the future of voting rights, abortion rights, healthcare, the economy—and so much more. And in many states, protecting key civil rights will come down to the results of a single race: governor. With five days to go until Election Day, I talked to two candidates I’ve had the privilege to meet through my work in civic engagement: Stacey Abrams, the voting rights champion from Georgia who could become the country’s first Black woman governor, and Katie Hobbs, the Arizona Secretary of State who oversaw the 2020 election administration and now finds herself in a tight race against Kari Lake. Both women are running for the highest office in their state, and the stakes couldn’t be higher. Ashley Spillane: You’re both running for governor. Tell me more about why this position matters. Stacey Abrams: Governors are the CEOs of the entire state, charged with implementing laws, crafting a budget, and overseeing state operations. Most people think of Washington, DC when they think about who has the greatest impact on policy, but the truth is…governors have the most impact on our lives. We know it is so important to have women in all kinds of leadership roles; studies have shown [corporate] female CEOs make better political leaders, are better with money, are better collaborators, and care more about others than their male counterparts. Having women serving in the highest state office willing to collectively lead important debates is critical. Over reproductive rights, of course—but also about voting rights, marriage equality, kitchen-table economic issues, and how our democracy as a whole should operate more equitably. Katie Hobbs: Despite making up over half the U.S. population, women constitute just 24% of the Senate, 28% of the House, and about 30% of all state legislative seats. Since its formation, 116 people have served on the Supreme Court; only six of them have been women, four of whom are serving now. Not to mention that literally every U.S. president who has appointed these judges has been a man. As for governors, there are only nine women in those roles right now. Many of them are seeking re-election this year. Some [candidates], like me, are running against anti-choice women, and others, like in Stacey’s race, are challenging male incumbents who have vowed not to use their veto pen to protect our rights. If legislatures pass even more of these cruel laws, governors are the last line of defense to stop them.  ARIZONA SECRETARY OF STATE, KATIE HOBBS. (IMAGE BY MARIO TAMA VIA GETTY IMAGES) Governors’ races seem more hotly contested this year. Why now? Katie: We’re at a crossroads for our democracy, and everyone’s realized the importance of state officials in protecting (or killing) it. I’m running against someone who denies the 2020 election results and has not said if she will accept the results if she or her party lose in the future. There are people running for governor, secretary of state, and attorney general across the country who are actively undermining our democracy and working to overturn the will of the people for their own political gain. Stacey: As the Supreme Court removes federal protections and devolves them to the states, governors will also serve as a last line of defense for your hard-fought rights. In this post-Dobbs, post-January 6 era, with voting rights and civil liberties at stake, women governors are positioned to lead a nationwide effort to take back the decisions that should be ours alone. Little girls growing up in this era, particularly little girls of color, are counting on women leaders.  Ashley Spillane is a social impact strategist, civic engagement expert, and founder/CEO of the (nearly) all-female firm, Impactual. Her work has been featured on The Washington Post, The New York Times, Harvard Business Review, Glamour, and Marie Claire. FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

What You Don't Already Know About Extremism

|

Greetings, Meteor readers, Happy Thursday before Halloween! We don’t want to spook you out too much, but the midterm elections are in 13 days. That is scarier than Freddie Krueger! This week, Meteor co-founder Cindi Leive spoke with journalist Kyle Spencer about what’s really behind the rise of far-right extremist groups on college campuses. Your horror movie marathon’s got nothing on the realities of young, college-educated men being trained to “weaponize” their cell phones against their peers. But before that, my colleague Shannon has rounded up a few more races to watch this year—and, of course, the news. Have a boo-tiful weekend! (I’ll see myself out.) 🥁 Samhita Mukhopadhyay   QUICK ELECTION MOMENTHere are three races we’ve got our eyes on this week, plus an action item from our friends at Supermajority. The Texas AG race - Some good news out of the Lone Star State! Democrat Rochelle Garza is running to unseat Ken Paxton as Attorney General, and she actually has a shot at winning, despite Texas’ reputation of always going red. Refreshing your memory, Paxton is not only anti-abortion but has pushed for anti-trans legislation, supports book banning in libraries, and even tried to criminalize family-friendly drag shows. It goes without saying, but I will say it anyway: There is so, so, so much at stake in this one race. The Michigan Secretary of State race - This one might be flying under your radar. But as Teen Vogue lays out plainly, this race is all about voting rights. So who’s running against sitting Democrat Jocelyn Benson? The Republicans selected Kristina Karamo, an election denier who believes the January 6 insurrection was orchestrated by “Antifa” members dressed up as MAGA supporters. Ironically, Karamo’s main platform is election integrity and security. According to Teen Vogue, Karamo was initially “[a candidate] of the America First Coalition, an organization that seeks to restrict Americans’ voting rights by creating barriers between them and the polls.” Still need another red flag? Karamo has Donald Trump’s endorsement. The Oregon Governor’s race - This showdown in Ducks country also needs more attention. While Oregon has been reliably blue, Rebecca Leber of Vox put together a fascinating overview of how special-interest groups and Nike co-founder Phil Knight have been chipping away at Oregon’s blue veneer. And the chisel is Republican candidate Christie Drazan, who is running against Democrat Tina Kotek and the unaffiliated candidate Betsy Johnson (no relation to the fashion designer). Climate action sits at the heart of this race. “If Drazan wins, Oregon would become the first state in the West to reverse course on its climate goals,” Leber reports. And that’s not hyperbole; it’s simply what happens when one accepts millions of dollars in campaign funding from a logging group with ties to alt-right militias. So now the question is, what can you do? (Other than vote. Have we mentioned you really need to vote?) This Saturday, Supermajority is hosting two events you can be a part of. The first is a virtual text bank with Megan Rapinoe and the #WomenAreVoting Coalition to encourage women voters in Georgia and North Carolina to get out and vote for the things we believe in. (IMAGE COURTESY OF SUPERMAJORITY) For anyone in Michigan, Supermajority is also hosting a Day of Action Canvass in Dearborn Heights where volunteers will go door-to-door sharing information on voter registration. PLUS:

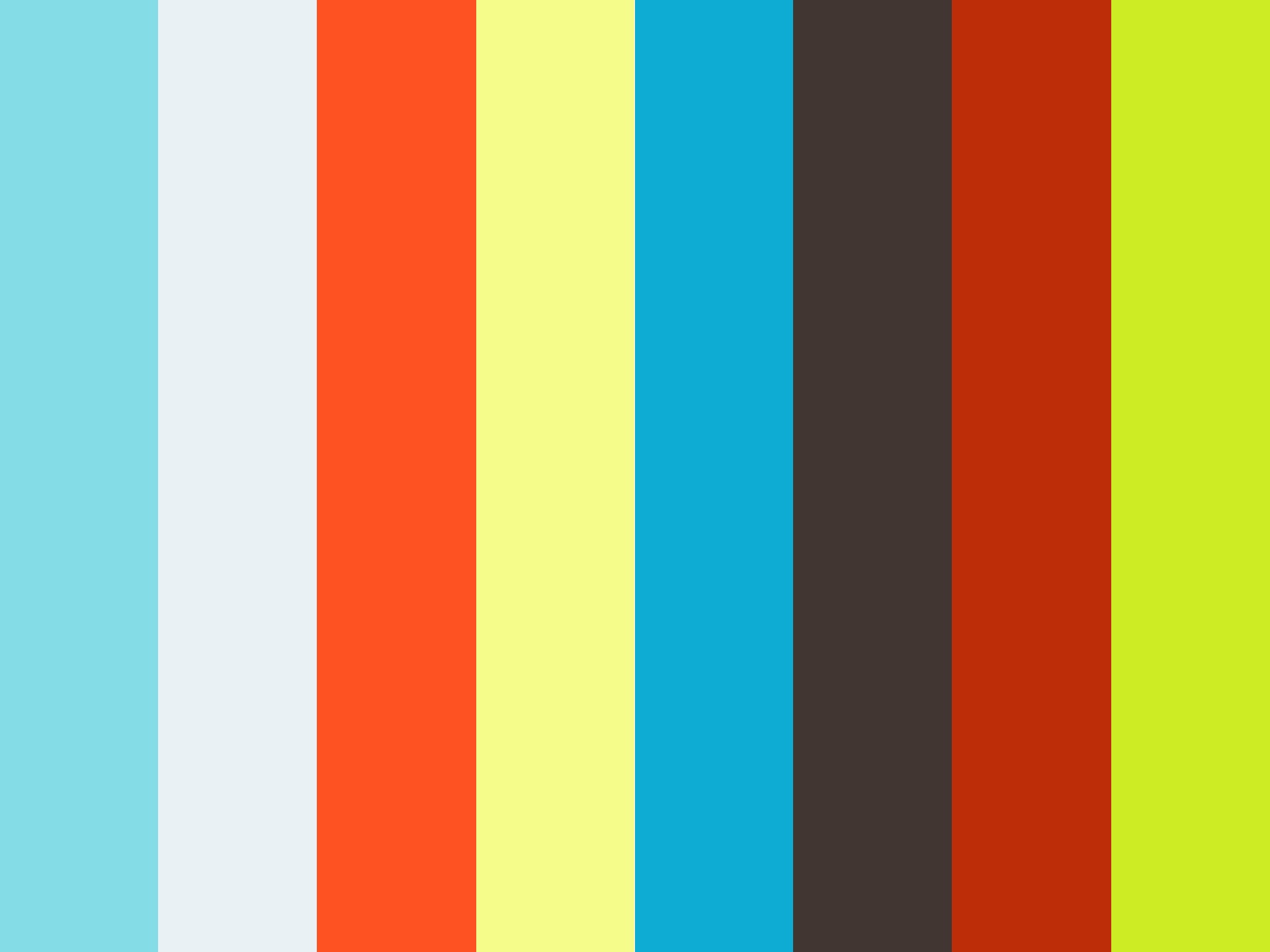

EXTREMISM WATCHThe Proud Boys Are Scary. These Organizations Are ScarierThat's the message behind a new book about the rise of the right on campusBY CINDI LEIVE  A YOUNG MAN ATTENDING AN "AMERICA FIRST" EVENT HOSTED BY TURNING POINT USA IN DECEMBER OF 2021. (IMAGE BY SPENCER PLATT VIA GETTY IMAGES) Extremism is everywhere: Election deniers are running for office. Antisemitism is on the rise. Proud Boys and Oath Keepers are regularly disrupting events, holding rallies, and threatening to interfere with elections. Not to mention the fact that friendly TV personality Dr. Oz now wants your local councilperson to have a say in your medical decisions. None of this is a surprise to journalist Kyle Spencer, who’s been embedded with the rising stars of this country’s increasingly visible and vocal right wing for the last four years—spending up-close time with right-wing activists like Charlie Kirk and Candace Owens, plus the young people who are joining their movement. All of this is documented in her new book Raising Them Right: The Untold Story of America's Ultraconservative Youth Movement and Its Plot for Power. I had questions. *** Cindi Leive: What are we getting wrong about what the right-wing really is in this country? Kyle Spencer: It kind of depends on whether or not you’ve been close to a college campus recently. I think there’s a lot of fear and concern about the Oath Keepers and the Proud Boys and these really aggressive groups that are openly radical. And they’re going after the kid in his bedroom playing video games all day…[But] I argue that, no, we should be more alarmed with these [groups] that are on college campuses recruiting people as if their ideas are really normal and mainstream. White boys are a very big target for them. And they often like to start with an issue that you care about. You know, if a kid [says], “Sometimes I feel like I can’t really say what I want,” they start there and then radicalize. But they sell it with a smile. And they try to stay really far away from political issues and stay more with culture. They’re very strategically and surgically trying to normalize ideas like gun ownership, nativism, [and] pro-American, anti-immigration sentiments, which veer very quickly into racism and, in some cases, anti-Semitism. And people don’t realize a lot of this actually is [campus] partnerships with the Christian right. To me, that’s the most alarming, [that they are pulling students into] this Christian nationalism. These really draconian ideas that, you know, God chose America. God runs America. The Constitution is a divine document. And the Bible is always above the Constitution. So much of what we hear about the cultural climate on college campuses focuses on the perceived “cancellation” of people on the right. I feel like I’ve heard more concern about that than I have about this phenomenon that you’re documenting. Is there a misperception of campus life? Yeah. It’s really a myth that there are all these free-speech issues on college campuses. Now, a lot of professors are pretty progressive. This is just a truth. But students are much more divided. I try to remind people that four in 10 young people voted for Trump in 2020. So this idea that young people are so radically progressive is just not true. What you see on these college campuses is, there are instances of intolerance among progressives. What these right-wing groups do is catch them and to edit them and throw them up on the Web to get them to go viral with the help of right-wing media outlets. One of the tools they use, obviously, is their cell phones, and they’re told in their training to “weaponize their phone.” So [the left-wing intolerance] is not nearly as prevalent as we’re told it is. And the reason is that they have created a national campaign [that] starts on the fringes—Breitbart and some of these right-wing college sites—and then bleeds into The Wall Street Journal. And eventually, The New York Times believes that this is a huge problem.  A PROTEST AGAINST RIGHT-WING SPEAKERS ON CAMPUS IN 2017. (PHOTO BY DAVID MCNEW VIA GETTY IMAGES) You said that they’re told in their training to “weaponize their phones.” Where are those trainings taking place, and led by whom? The Leadership Institute is the conservative training academy. It received $25 million last year. It was started in the seventies. Everybody that you know that’s a right-wing activist went through the academy: Tucker Carlson, Karl Rove, Pence. And so what happens is that everybody speaks the same language because they were all trained in the same place. So when you say “weaponize your phone,” everybody knows what you’re talking about. When you say “I’m willing to bleed for the cause,” everybody knows what you’re talking about. If you refer to a “3 a.m. type,” you’re starting your college group, and you’ve got to find the people you can call at 3 a.m., hard workers. Everybody knows. They have this whole vocabulary—which the left does not. They’re all talking the same language. And every [right-wing] donor—wealthy, mid-tier, low-tier—they’re going to give a little money to the next generation, and a lot of it goes through the Leadership Institute. Which, again, is not what [the left] does. You’re making a distinction between this movement and the dark underbelly of Oath Keepers, Proud Boys, and Q Anon. But do these groups intersect? What these folks do a lot is kind of wink at the [fringe] right. But the distinction is that the groups that I’m writing about [like Turning Point USA] are baked into the establishment. They’re funded by the establishment. That’s why they’re scarier. And they have a lot more money. You’ve talked about religion and anti-immigrant sentiment as being big motivations for people to join these groups. How much of this has to do with white men feeling—incorrectly—like they’re the most attacked group on the planet right now? It’s central. I’d almost like to find a more complicated answer. But I think that this fear and anxiety among white men that they’re ceding power to people of color and to women—this replacement theory—is extraordinary. And I think what we’re seeing is that anxiety playing itself out. And for women [who join these groups], they can be receptive to [these] ideas…but most of the young women I talked to [already] came from conservative families. I didn’t see as many women being “turned”—I saw boys being turned. A lot of boys came from moderate or Democrat families. You reeled off that scary figure that four in 10 young people voted for Trump in 2020. We’re just a couple weeks away from these midterms. What’s your sense of the appeal of the right to young voters right now? What I saw a lot on college campuses is not that these right-wing groups were able to [persuade Democrats to vote Republican]. What they were able to persuade them to do was not go to the polls. It’s a kind of hidden voter suppression: They’ll just kind of pound, pound, pound: “Joe Biden’s an idiot. He’s falling off his bicycle.” “These lefties on campus won’t let you say what they want. And they support affirmative action, which means slots taken away from you.” And they just keep pounding it, but they turn people off from the Democrats so they don’t go to the polls. So if we see a relatively low voter turnout, it would be a sign to me that these guys are continuing to be successful with this. But I don’t know. I mean, I’m not going to lie. I don’t know how it’s going to go. Neither do you. Nobody does.  Cindi Leive is the co-founder of The Meteor, the former editor-in-chief of Glamour and Self, and the author or producer of best-selling books including Together We Rise.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

Do NOT Ignore These Midterm Races

|

Greetings, Meteor readers, This weekend I sojourned into the forests of upstate New York to be one with the leaves and listen to Midnights on an endless loop. And while that was great, it was also a bit alarming to drive past confederate flags, enormous signs that read “Fuck Biden,” and—for the local flavor—a few disparaging posters about Governor Kathy Hochul.  This feels like the perfect time to remind all our New York readers that Hochul and her opponent Lee Zeldin are on the ballot this November 8. And Zeldin is an anti-abortion Trump supporter who is now surging in the polls. This is not the time to assume blue states will stay blue no matter what. As far as the national landscape goes: In today’s newsletter we’ve got a refresher on the midterm races we have our eye on, the candidates who say they will fight for bodily autonomy—and of course, the news. Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONNo justice for BG: WNBA star Brittney Griner, who was detained in Russia in February after officials found cannabis oil cartridges in her luggage, has lost her appeal and will officially be serving a nine-year sentence in a Russian penal colony. Griner’s 250-day detention in Russia was officially recognized as a wrongful detention by the U.S. government in May, and the Biden administration tried for a prisoner swap in July, offering up Russian arms trafficker Viktor Bout in exchange for Griner and fellow American detainee Paul Whelan. But the attempt came to naught when the Russians chose to counteroffer instead of following through on the swap. Unless the U.S. finds another way to intervene, it is very likely that Griner will remain in Russia until the end of her sentence.  BRITTNEY GRINER APPEARS IN COURT DURING HER TRIAL IN JULY. (IMAGE FOR THE WASHINGTON POST VIA GETTY IMAGES) Eyes on the prize: Election Day is two weeks from today, and state races have never been so crucial. What happens this November will lay the groundwork for months, even years to come—partly because the state legislators and attorneys general who are elected this fall will be the ones ruling on the outcome of the presidential race in 2024. And if the Republicans have their way, the “red tsunami” could reawaken the Ghost of Orange Presidents Past—and that is NOT the spooky season I signed up for. For the next two weeks, we’re going to pull out a few key races we have our eye on: Georgia - There are several heated races in the peach state. As you probably know, Reverend Raphael Warnock is locked in a tight race defending his U.S. Senate seat against Trump-backed Herschel Walker, who recently had to shift his tune on abortion rights when a woman claimed she was paid by Walker to terminate her pregnancy. But as you might not know, there are also four proposals for changes to the state’s constitution on the ballot; voters can read up on them here. One proposal could change how property owners are taxed after their properties are damaged or destroyed by a natural disaster, a hugely important change considering the extreme weather we’ve been seeing across the country. And last, but never least, Stacey Abrams is running for Governor against incumbent Brian Kemp. Abrams is a leader in voting rights and she has promised to fight for abortion rights. If elected, she will be the first Black woman governor in American history. Pennsylvania - TV doctor, Republican, and New Jersey native Mehmet Oz is up against Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman for the state’s open U.S. Senate seat. Fetterman is still leading in the polls, but Oz has been rubber-stamped by Trump and Mitch McConnell—which means anything can happen. Let’s also not forget that after Fetterman suffered a stroke and was unable to attend an in-person debate, Oz used that as fodder for smear campaigns. What happened to first do no harm? Nevada - The race between incumbent Democrat Catherine Cortez Masto and Republican challenger Adam Laxalt for U.S. Senate is according to CNBC, “one of the GOP’s best chances to flip a blue seat red.” Laxalt has been wooing voters with a “tough on crime” platform backed by local police groups, while simultaneously attacking the FBI on behalf of Donald Trump. Like too many other high-profile GOP candidates, Laxalt has also been regurgitating the far-right’s claims about voter fraud in 2020. Meanwhile, Cortez Masto has worked to draw attention to the crisis of missing Indigenous women.  AND:

Please share this newsletter with anyone who needs to be reminded that elections are coming. FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()