Break Up With the Manosphere

We’ve seen what the bros have built. We can do much better.

BY SHANNON WATTS

It feels like months since Donald Trump took office, but it was just 12 days ago. In that short time, we’ve experienced the whiplash of executive orders, confirmations, and quiet erasures of government workers. Dangerous cabinet members have been confirmed. Diversity and equity gains were gutted with the stroke of a pen. The federal government’s reproductive rights webpage disappeared overnight as if it had never existed (but here’s the archived version). The chaos is all-consuming—each move expected, yet somehow still landing like a fresh gut punch.

Trump is operating from the playbook he promised voters, but watching men whose own family members have accused them of predatory behavior march into positions of power while women are marginalized feels like a full-throated “fuck you” to feminism. It’s as if the men who are now in power are hellbent on rolling back all of the progress women have made since the 70s and they’re reveling in their revenge.

To be clear, Trump’s victory wasn’t just an election loss for the majority of American women who voted against him; it was a cultural rejection of female power facilitated in large part by the manosphere—a toxic, hyper-masculine echo chamber of podcasters, influencers, and bloggers who have spent years weaponizing misogyny. Their movement laid the groundwork for this moment, and right now, it feels like they’ve won.

A little history

The manosphere gained early visibility during flashpoints like GamerGate in 2014, where online harassment campaigns targeted women in gaming and tech, and the horrifying 2014 Isla Vista shootings by Elliot Rodger, who left behind a manifesto filled with misogynistic grievances. These events reflected a growing backlash to the rise of feminist blogs like Jezebel, the increasing mainstreaming of feminism, and women’s voices being amplified in previously male-dominated spaces. This toxic ecosystem grew to include communities like incels (involuntary celibates), Men Going Their Own Way (MGTOW), and Men’s Rights Activists (MRAs), which have long framed feminism as a threat to their identity and power.

But as I sit with the weight of it all, one thing has become clear: if we are going to successfully combat this backlash, we have to build something stronger than outrage alone. Online activism has played a critical role in mobilization and awareness for progressive causes—just as it has for the manosphere—but it’s not enough on its own to win. We need spaces for women in every arena: online, in real life, in activism, in community, and in joy.

We need a womansphere. Because the antidote to the manosphere isn’t just resistance—it’s connection.

The manosphere certainly creates connections but around the worst things. Modern-day manosphere leaders like “alpha” strongman Elliott Hulse, who preaches male dominance and rails against feminism, and far-right provocateur Nick Fuentes, the “your body, my choice” jackass who never met a nazi salute he didn’t like, exploit this resentment toward women, promoting hyper-masculinity as a cure-all for a world they claim is dominated by “woke” ideologies. Their messaging finds fertile ground in online forums like 4chan and Reddit, where misogyny and grievance politics are celebrated. Figures like Andrew Tate openly normalize violence against women, while he currently awaits trial on human trafficking and rape charges.

The manosphere now actively recruits vulnerable young men through everything from bodybuilding forums to gaming livestreams, and thrives on creating enemies: women, feminism, and anyone challenging the status quo. Fear, blame, and division remain the cheap fuel that powers this system, pulling in disillusioned men and weaponizing their grievances against progress.

After the election, it felt as if the manosphere was unstoppable. But then I received an invitation to attend a meeting in San Jose with a group called the Gigis, a community created for “midlife women to gather, grow, and give back.” This regular gathering of nearly 60 women wanted me to lead them in a discussion about what they could do in the aftermath of the election. During our two-hour meeting, some of the women said they were exploring a run for office. Others were starting nonprofit organizations to serve their neighbors. And others were going back to school to hone their activism skills. But all of the Gigis were committed to coming together to encourage each other to keep going.

Like the manosphere, this is a community, and the point of communities—of all types—is to help us find our purpose, test and hone our values, and be a part of something greater than ourselves. I’ve seen firsthand through Moms Demand Action that communities are where the real change happens—in ourselves and in the world. Not only is Moms Demand Action one of the largest grassroots organizations in the nation, but it’s also the largest real-life laboratory for helping women find their people and, in turn, their power. And that’s where we need to focus our energy: on creating in-person spaces that inspire connection and collective action. Unlike the manosphere, which thrives online by feeding on anger and fear, what I’m advocating for is grounded in real, face-to-face relationships, that foster compassion and collaboration. That’s the crucial difference between their network and what I’m calling the womansphere—we don’t just build ideas, we build bonds.

The manosphere understands that people crave belonging, even if their version rallies around a fear of inadequacy. But a healthy community—even if it’s just a handful of people—can help us feel connected to others and feel like we're part of something larger than ourselves. The manosphere thrives on reinforcing outdated power structures. The womansphere reimagines them entirely, creating a space for equity, inclusivity, and growth. Online and offline, where women can connect without fear.

Sitting with the Gigis—knowing that women everywhere, of all different walks, are meeting in their own groups—I realized that the most effective resistance to the Trump administration won’t be en masse, but underground—and it will start in small communities. We need a womansphere where we can come together in person from all walks of life to feel empowered, supported, and seen. We need in-person communities where women can have conversations, despite their levels of education or political views. We need more media and platforms to lift up women’s stories, leadership, and solutions. We need to celebrate and center diverse leadership and lived experiences. And we need to create a womansphere that is as loud and visible as the manosphere, but infinitely more constructive.

To be clear, I’m not talking about the existing “tradwife” communities, where women advocate for a return to regressive, hyper-traditional gender roles and use “feminine wiles” as power. Our womansphere is about real progress, inclusivity, and collaboration—not performative or nostalgic ideas of femininity. The womansphere isn’t just a rejection of toxicity; it’s a blueprint for a better, inclusive future.

The manosphere won’t go down without a weird, gross fight. Right now, they’re gloating, emboldened by political wins and all those inaugural ball invitations. But that’s all the more reason to double down on creating an alternative. In this moment, women, as always, face the harder job. Instead of tearing things down, we’re tasked with building something meaningful, something that endures. We need to work towards something, not against it. And while feminist spaces have historically had their own moments of conflict and division, this new womansphere can learn from the past and make constructive collaboration its guiding principle.

Build your community. Find your people. Start the conversation. This isn’t about perfection; it’s about progress. The womansphere starts now, and it starts with us.

And seriously, our content is way better anyway. Here are a few ways to enter the womansphere:

Podcasts

- America, Who Hurt You?

- Pulling the Thread

- The Amendment

- News Not Noise

- My So-Called Midlife with Reshma Saujani

- Not Gonna Lie with Kylie Kelce

- UNDISTRACTED, with Brittany Packnett Cunningham

Mission Driven Groups

- National Women's Defense League, a nonpartisan organization dedicated to preventing sexual harassment and protecting survivors.

- TOGETHXR, a media and commerce group founded by some of the world’s greatest athletes.

- Women in AI (WAI), a nonprofit do-tank working towards inclusive AI that benefits global society.

- Project Dandelion, a women-led global campaign for climate justice.

- GenderLib, an emergent and innovative grassroots and volunteer-run national collective that builds direct action, media, and policy interventions centering bodily autonomy

- Moms First, grassroots community of moms and supporters taking action in their homes, workplaces, and communities.

Inclusive Journalism:

- The Persistent, a digital journalism platform committed to amplifying women's voices, stories, ideas, and perspectives.

- The 19th News, an independent, nonprofit newsroom reporting on gender, politics and policy.

- them, the award-winning authority on what it means to be LGBTQ+ today — and tomorrow.

- The Gist, a women-led, inclusive, and empowering sports community made for everyone.

- The Meteor, a multimedia company centering the lives of women, girls and nonbinary people. (Hi, that’s us!)

Social Media Darlings:

Emily Amick (@emilyinyourphone)

Your Virtual Anti-Disinformation Bestie (@the.wellness.therapist)

Becca Rea-Tucker (@thesweetfeminist)

Shannon Watts is an author, organizer, and speaker. She founded Moms Demand Action and recently organized one of the largest Zoom gatherings in history, mobilizing women voters for the 2024 Kamala Harris campaign. Her new book Fired Up is coming in 2025.

“You can’t rewrite a statute with a Sharpie”

January 30, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, Too much is happening at once.  In today’s newsletter, we take a close look at the many anti-DEI actions Trump has put in motion, and what they mean in real life. Plus, what to expect at this year’s Grammys. Resting my eyes, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONThe ripple effects of the DEI crackdown: The morning after the aircraft collision over the Potomac River on Wednesday night, Trump was busy blaming the DEI policies of Biden and Obama for the crash. “Their policy was horrible,” he said, “and their politics was [sic] even worse.” His evidence-free rant is just the latest move of his administration’s obsessive, all-out assault on diversity, equity, and inclusion programs. So what do Trump’s slew of executive orders, freezes, and attacks on programs that help people of color, women, and LGBTQ+ people thrive actually mean? Before we parse out what we should expect, let’s first review what’s happened. On his very first day, Trump overturned Biden’s executive order on DEI, which, among other things, ordered all federal agencies to come up with equity action plans, which address discrimination in the workplace. The second Trump executive order, handed down the same day, went further, ending any DEI activities in the federal government and reversing core policies that have been around for decades, including a Lyndon B. Johnson-era order that required any workplace taking federal dollars to implement equal opportunity measures. The Trump administration made clear just how much they mean it: Tens of thousands of federal employees got an email directing them to report any colleagues trying to “disguise” DEI “by using coded or imprecise language” and promising that they’d face “adverse consequences” if they didn’t. This effort extends throughout the government. The Department of Justice was ordered to halt ongoing cases in its civil rights division, including police reform agreements negotiated in the final days of the Biden administration. The Department of Education removed more than 200 web pages with guidance for schools on how to implement DEI policies and create welcoming campus environments. And just last night, Trump issued an order that threatened to remove federal funding from schools teaching about things like transgender identity, white privilege, and unconscious bias (though it’s unclear how much of this will actually happen, given how difficult it is for the federal government to dictate curricula.) So, are you ready for the hopeful part? “These executive orders cannot change civil rights law,” says Amalea Smirniotopoulos, senior policy counsel at the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund. “You can’t rewrite a statute with a Sharpie.” That means that hiring, say, only white people is still illegal. Denying a woman a promotion just because of her gender is still illegal. Firing someone for being gay is still illegal, even according to the rightwing Supreme Court. Which also means that if any federal employee experiences discrimination or workplace harassment, they still have rights under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act and can file a lawsuit against the federal government. And despite the administration’s attempt to frame DEI programs as “illegal and immoral,” the programs it’s ending “are lawful and have been upheld by courts in many cases,” says Smirniotopoulos, pointing to the NAACP’s success in winning an injunction to stop an anti-DEI executive order issued by Trump during his first term. She predicts these newer orders will face challenges, too. But that doesn’t mean this crackdown won’t have far-reaching effects. There’s the law, and then there’s enforcement. “The reason DEI programs exist in the first place is to help with compliance of civil rights laws,” Smirniotopoulos says. “If we see the federal government roll them back, there is a risk that they’ll allow discrimination to fester among their own workforce.” In other words, you’re still free to file a lawsuit alleging discrimination—but the guardrails and systems that might discourage discrimination to begin with may be deteriorating. This deterioration could be widespread, given how the current administration is “encouraging” the private sector to roll back DEI. Since the election, many private companies—from Walmart to McDonald’s to Amazon—already have. Anti-DEI efforts will also rob federal employees of things like volunteer affinity groups. “Employees are feeling that the loss of these programs [will deprive] them of community and the social network that’s essential in any workplace,” Smirniotopoulos says. “Your ability to succeed in your workplace isn’t just about your raw intelligence, it’s also about knowing how to navigate workplace dynamics, knowing the culture and norms. Those social factors can play just as much of a role in whether someone can thrive or get promoted.” For the federal government, the ultimate effect may be a working environment where swaths of the population feel unwelcome—which will hurt hiring and retention for government positions. (Many suspect this is part of the point; the president of the American Federation of Government Employees called the anti-DEI orders “a smokescreen for firing civil servants.”) A diminished federal workforce affects everything from getting through airport security quickly to making sure we have clean water. “When the federal government works well, it’s invisible,” Smirniotopoulos says. “When the federal workforce is attacked, that ultimately hurts all of us.” If you’re experiencing workplace discrimination or harassment: The Equal Opportunity Employment Commission technically still exists, but to be safe, we recommend contacting independent organizations like the ACLU, NAACP, or National Women’s Law Center to get advice on how to proceed. —Nona Willis Aronowitz AND:

Two Pop Stars, Both Alike in DignityBeyoncé and Taylor Swift face off at the GrammysBY SCARLETT HARRIS  IN FAIR LOS ANGELES WHERE WE LAY OUR SCENE, FROM ANCIENT GRUDGE BREAK TO NEW MUTINY. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) It’s been an incredible year for women in pop, and this weekend at the 67th Grammy Awards the race for the highly coveted Album of the Year award is stacked with the gals who ruled the summer. Billie Eilish, Sabrina Carpenter, Chappell Roan, and Charlie XCX are among the nominees. And while each of these women has a strong chance of taking home the gold, the real competition is between two titans of the industry—Taylor Swift and Beyoncé, who have 157 nominations and 46 wins between them. This weekend promises to be a kind of referendum on the notoriously racist and old-fashioned music establishment. All eyes will be on whether Bey, with “Cowboy Carter,” can finally clinch the Album of the Year award that has eluded her her entire career—or whether Grammy darling, Swift, will add to her already record-breaking tally of four AOTY golden gramophones with “The Tortured Poets Department.” The last time they were pitted against each other in this category was at the 2010 Grammys, for “I Am… Sasha Fierce” and “Fearless,” respectively, which Swift went on to win. This followed Kanye West’s infamous “I’mma let you finish” screed at the MTV Video Music Awards the year prior, in which he interrupted Swift’s acceptance speech for Best Female Video for “You Belong With Me,” asserting that Beyoncé had one of the best videos of all time and should have won for “Single Ladies (Put a Ring On It).” (He wasn’t wrong.) Ever the consummate professional, Bey had invited a deer-in-the-headlights, 19-year-old Swift back on stage during her own acceptance for Video of the Year so she could give the speech truncated by West.  WEEKEND READING 📚On stoking division: Anti-immigration policies are creating a wider divide in already fragile Latine communities. One Mexican/Puerto Rican writer shares what that looks like for her family. (New York Times) On letting the dead rest: A new documentary about Selena Quintanilla called Selena y Los Dinos has some wondering where to draw the line between honoring late artists and profiting off their tragic stories. (Refinery 29) On sex and other cities: A new character has emerged from the manosphere: the “passport bro.” While that may sound like a cool name for travel buddies, it’s just the latest depraved rebrand of sex tourism. (The Baffler)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

"They Deserve Better Than Bobby Kennedy"

January 28, 2025 Happy Tuesday, Meteor readers, Before we get into the news of the day, one important question: Have you filled out our survey yet? It’s the best way to take our relationship to the next level. Think of it like calling your senator, but more fun! In today’s newsletter, it’s confirmation time again, and we’re at the edge of our seats. Plus, some pardons you may have missed. Serving surveys, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONMaybe say no this time?: Tomorrow the Senate confirmation hearings begin for Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., who is in line to become the next Secretary of Health and Human Services. This guy is a sack of contradictions: Before he became a Trump loyalist, RFK, Jr. was an environmentalist warning consumers about the dangers of pesticides and a co-founder of the Waterkeeper Alliance. Cool. But he also led an anti-vaccine advocacy group and has repeatedly spouted theories that go against longstanding science and medical research. His greatest hits include: Wi-Fi causes cancer, chemicals in water cause “sexual dysphoria” in children, and HIV is not the sole cause of AIDS. (Tell that to this French virologist.) So he’s not exactly suited for any job at Health and Human Services, let alone the top one. Of course, he wouldn’t be a Trump nominee if there wasn’t also an allegation of sexual assault dangling over his head. During RFK, Jr.’s bid for president, as we’ve reported before, his family’s former nanny Eliza Cooney alleged that he groped her multiple times in the late 1990s. The Washington Post also reported today that RFK Jr.’s cousin, Caroline Kennedy, spoke out against his nomination, calling him a “predator” who targeted parents of sick children. In a letter to lawmakers denouncing her cousin, Kennedy added that HHS employees “deserve a stable, moral, and ethical person at the helm of this crucial agency. They deserve better than Bobby Kennedy—and so do the rest of us.” In other words, senators will yet again be sitting down with an unqualified and potentially dangerous white man to assess whether or not he is fit to have a job that the average American and 24,000 physicians can plainly see he cannot do. But there is still some hope here. Last week’s confirmation of alleged abuser Pete Hegseth for Secretary of Defense was a 50/50 vote, with Vice President J.D. Vance casting the tie-breaker. If every Democrat and even a small handful of Republican senators vote no on Kennedy, then the confirmation won’t pass. (Here are all the members of the Senate Finance Committee, if you’re wondering who to call.) A report from the Wall Street Journal has already identified two GOP senators who could go either way on the vote: pro-vaccine senator Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and James Lankford (R-OK), an anti-abortion senator who’s wary of RFK, Jr.’s previously pro-choice stance. Polio survivor Mitch McConnell (R-KY) has also warned that any nominee should “steer clear” of undermining the polio vaccine and reportedly refused to meet with RFK, Jr. Even Mike Pence is opposed to this appointment, and it’s infuriating that any of us have to agree with Mike Pence on anything. To those senators still on the fence, I also have to ask: Is approving this man worth the message it sends to the millions of women like Eliza Cooney who have to sit and watch their abusers continue to rise? As Cooney put it: “We can do better.” AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

No trial? No Problem

January 23, 2025 Salutations, Meteor readers, I love Ben Shelton more than I ever have. Ben, if you’re reading this, I want you to know that I will personally go to Australia and yell at all the broadcasters who are trying you this week. Save your energy, I got you.  In today’s newsletter, we go over a bill speeding toward Donald Trump’s desk. Plus: an emergency contraceptive newsbrief, an update on the “slut puppy” court case, and your weekend reading list. See you at the semis, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONDue process for some: Congress has passed the Laken Riley Act, named for a young woman in Georgia who was killed by a Venezuelan undocumented immigrant, and will be sending it to #47 to be signed. It will be among the first laws passed by his administration (although his hand must be tired from the other stuff he’s been signing) and it is ominously fitting that the first piece of legislation he executes is an anti-immigration bill. So what’s in the bill? The top line item is that any undocumented immigrant accused of non-violent crimes like theft, either in the U.S. or their home country, will now be subject to mandatory indefinite detention by ICE. They will not be allowed bond hearings in their criminal case and, once in ICE custody, can be held until deportation, which will be the most likely outcome if they’re unable to leave the detention center for preliminary trial hearings. The bill also allows for state attorneys general to sue the federal government on behalf of residents who believe they’ve been harmed by immigration policies. To be clear, there are already policies in place for detaining and deporting convicted violent offenders. But this bill expands those policies to include anyone arrested or charged with “theft, larceny, burglary, shoplifting” or assault against a law enforcement officer, regardless of any conviction or lack thereof. “What's dangerous about this bill is that it takes away some of the basic fundamental due process tenets of our legal system," one legal expert told NPR. This bill is a direct response to the particulars of Laken Riley’s case: The man who murdered her had previously been charged with shoplifting, and supporters of the bill argue that had he been deported after that minor crime, Laken Riley would still be alive. That is possible—but overriding the Fifth Amendment for a vast number of people is not a sensible way to protect women from being murdered. (Riley was one of the roughly 2000 women killed by men in this country every year. Fortunately, in response to these crimes, two years ago, the White House formed the first-ever government plan to end gender-based violence… Oh, wait.) The Laken Riley bill isn’t just a GOP favorite; 12 Democrats voted for it, too—see which here—which shows just how many people believe that immigrants to the U.S. commit more crimes than its citizens. (Which, of course, is demonstrably false.) Immigrants have long been used by the GOP as boogeyman responsible for America’s troubles, and now they’ve got the tools they need to disappear as many as possible. AND:

WEEKEND READING 📚On what’s next: Could having an accused rapist returning to the White House be a death knell for the #MeToo movement? That’s the MAGA movement’s hope. (The 19th) On a bad start: Puerto Rico’s new Trump-supporting governor has been at work for nearly a month. Things haven’t been going well. (The Latino Newsletter) On film: The “worst movie of the year” just got nominated for 13 Oscars including Best Picture. (Slate) On the inauguration: This week on our own UNDISTRACTED, Brittany Packnett Cunningham assembles her group chat to break down the excruciating spectacle of Martin Luther King Day coinciding with the inauguration. It’s a conversation about the price the country has paid for the success of Barack Obama, Trump’s demonizing of DEI programs and his ironic love of meritocracy. Or, as Dr. Brittney Cooper puts it, “The idea that America is a meritocracy when Donald Trump is the president is a white boy’s wet dream.” You can catch the full episode here.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

It's Mt. Denali If You're Nasty

January 21, 2025 Fair Monduesday, Meteor readers, I spent most of my day yesterday guiding my child around the Liberty Science Center along with what felt like every other kid in New Jersey. What did I miss? If you, too, pulled a Michelle Obama and sat out the day’s events, we’ll catch you up: In today’s newsletter, we wrap our heads around the sweeping pardons granted to January 6 insurrectionists. Plus: what Cecile Richards would want us to do. ♥️ ✊🏼, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONThe longest Day One ever: Yesterday, shortly after he was sworn into office (with his hand not on the Bible), Donald Trump grabbed his favorite sharpie and started signing a flurry of executive orders, including reinstating the death penalty, declaring that there are only “two sexes,” laying the groundwork for more oil drilling in Alaska, and mass pardoning nearly every January 6 rioter. (Even this guy). And we haven’t even gotten to his attempt to rewrite the Constitution to eliminate birthright citizenship. (States are already suing over this.) While you can point to nearly every order signed and find something frightening, let’s focus for a moment on the January 6 move—which wipes out more than 1200 convictions, dismisses over 300 pending cases, and commutes the sentences of 14 violent, racist, and seditious rioters who sought to overturn an election with which they disagreed. That means that every person currently serving a prison sentence will be released, including the leader of a self-described anti-government militia. The pardons and commutations also mean that anyone convicted of a felony will have their full legal rights restored. Do you know what felons can’t do after a conviction? Legally purchase guns. But these people now can do that, and they are thrilled. This isn’t just an incidental ripple effect of the pardons. Rather, with the stroke of a marker, Trump has signaled, as several counterterrorism experts voiced to reporters at NPR, an “endorsement of political violence…as long as that violence is against Trump's opponents.” For followers of the Oath Keepers and the Proud Boys, this is very good news: Their ally in the White House has greenlit whatever they might do and the guns with which to do it. But for the rest of us, it raises real, unsettling questions: What does the future of political protest look like when the opposition has become so emboldened? For me personally—a Puerto Rican Muslim—the prospect of a rejuvenated and protected modern-day KKK fills me with dread and fuels a deep-rooted mistrust I’ve had for years. There’s a pit in my stomach any time I go to the “good” grocery store and see white men walking the aisles. Is he one of them? Am I safe here? I have renewed doubts about the white people in my life. Would they stand up for me? Would they even know they needed to? With Trump rolling out all of the horrible things he’s promised, I am mentally exhausted and emotionally drained—and it’s only been a day and a half. But all of that is the point. Fear is paralytic. It is divisive. It is distracting. It is the master’s tool. And when we think about what it will take to live through a second Trump presidency, the first unavoidable step is learning how to operate beyond fear. I don’t say that lightly; I say this as someone who is in the pit with you. Surviving this administration will demand an enormous amount of work from every single one of us. And that work has to be based in community, or it will not survive the years ahead. Maybe that’s joining a PTA or neighborhood association, or running for school board. It could be working against gun violence. It could be running for city council or county commissioners office. It could be volunteer work or handing out supply kits to the unhoused or donating to local drives. I also suggest engaging in the simplest act of defiance there is: reading. Go to your library and learn from those who fought these rights before we even got here. Read Audre Lorde. Read James Baldwin. Read Iris Morales. Read Angela Davis. Read Grace Lee Bogs. Read bell hooks and keep reading until you read yourself out of fear and into readiness. There is no white hood, no “Roman Salute,” and no executive order stronger than what we can do together. AND:

DIVINE. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

CECILE RICHARDS FOREVERYesterday morning, hours before we inaugurated a president who campaigned on his disdain for women and for democracy, we lost a woman who crusaded for both those things. Cecile Richards was probably our country’s best-known abortion-rights advocate; she led Planned Parenthood for a decade, testified for 12 hours before a hostile Congress, and helped launch Supermajority, Charley, and Abortion in America. She was also funny, determined, and cheerfully relentless; she gave spot-on advice, sized people up perfectly, and adored her brand-new grandson Teddy (when I typed her name just now, her contact auto populated and a picture of him in a little red onesie popped up on my screen). She was a mentor and a hero, to those of us she knew and to plenty she didn’t; if you had lunch with her, women would approach with tears in their eyes and a story you could tell they wanted to share. And she is gone far too soon: at 67, of a brain cancer that could not stop her from speaking on behalf of Kamala Harris at the convention last summer. The daughter of Texas governor Ann Richards, Cecile understood organizing (and the strength of women) on a cellular level. Those are two things we need more than ever right now. We need Cecile, to be honest, but in her absence, we need each other. And as her family wrote yesterday, “We’ll leave you with a question she posed a lot over the last year: It’s not hard to imagine future generations one day asking: ‘When there was so much at stake for our country, what did you do?’” And she said, of course, that there was only one answer: “Everything we could.” —Cindi Leive   FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

What to Expect on Day One

January 16, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, There’s a whole bunch going on ahead of Monday’s inauguration, so let’s get straight to it. In today’s newsletter, Nona Willis Aronowitz examines the more than 100 executive orders Donald Trump reportedly plans to sign during his first days in office. Plus, a little news, and your weekend reading list. Running on coffee and optimism, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONHow Trump plans to “flood the zone” on Day One: We’re only a few days from the beginning of Trump 2.0, and if the president-elect is to be believed, Inauguration Day will be one of “shock and awe.” That’s not because of anything you’ll see at the actual event; it’s because, as Trump told GOP senators in a private meeting last week, he’s preparing more than 100 executive orders for Day One. In case you need perspective: That’s a lot. President Biden, for example, issued just 17 orders on his first day (and 156 during his entire presidency thus far). Trump has long been planning to push the limits of his executive powers, and this first-day onslaught is an early sign that he’s serious. (Compare it with 2017, when Trump, shocked he had won, signed a grand total of one order on his first day and then basically took the weekend off.) The EO onslaught is an example of Steve Bannon’s infamous “flood the zone” theory: Disorient the media and political establishment with so much information that they’ll be forced to prioritize only the wildest of the wild, letting the rest sail through. So what will the zone be flooded with Monday and Tuesday? Here’s what to expect. Immigration and border restrictionsMuch of Trump’s Day One will likely be focused on immigration. (Homeland Security adviser Stephen Miller, one of the most notorious ghouls of the first Trump term, was present for last week’s meeting with senators.) Some initial orders may include…deep breath…reinstating the Muslim ban; declaring illegal immigration a national emergency; ordering the building of detention facilities; withholding federal funds to sanctuary cities; ending Biden’s humanitarian “parole” programs; finishing the U.S.-Mexico border wall; and even, potentially, closing the U.S.-Mexico border altogether, probably by citing a public health emergency.  ACTIVISTS AND MIGRANTS STAGED A PROTEST AGAINST TRUMP'S PROPOSED MASS DEPORTATIONS AT A U.S.-MEXICO POINT OF ENTRY LAST MONTH ON INTERNATIONAL MIGRANTS DAY. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Perhaps most consequential of all, Trump has repeatedly signaled that he plans to end birthright citizenship, a constitutional right that grants citizenship to any baby born on U.S. soil. “We have to end it,” he has said, calling it “ridiculous” and claiming falsely that we’re the only country that grants it. (More than 30 nations have unrestricted birthright citizenship.) It’s a blatantly unconstitutional move that would get challenged in court, but all it takes is five Supreme Court justices to find wiggle room in the 14th Amendment. Climate and energy rollbacksAnother big Day One priority? Undoing Biden’s attempts to protect the environment. Trump says he has plans to lift various restrictions on fossil fuel production, reverse bans on offshore drilling and fracking, pull out of the Paris climate agreement (again!), and revoke waivers allowing states to strictly regulate pollution—all setbacks that would make the U.S.’s climate goals even further out of reach. He has also made a Day One promise to end what he calls the “electric vehicle mandate,” which refers to incentives and tax breaks for buying and making electric cars. The Republicans have long wanted to quash EV sales, but experts say the market and Detroit automakers may decide otherwise. (And Elon Musk may prove to be a “wild card.”) Anti-trans movesTrans people will be in the crosshairs on Day One, too: Trump has said he plans to reinstate and expand the policy banning them from military service, block them from competing in women’s sports, and prohibit trans minors from receiving gender-affirming care. These orders may very well be redundant, given the cruel legal and congressional efforts already underway, but perhaps not if your priority is to inflict pain on the trans community as swiftly as possible. …and a smattering of other issuesTrump has talked early and often about pardoning January 6 prisoners, though he’s sent mixed messages about exactly who he’ll spare. He’ll probably reinstate his expanded version of the global gag rule, which prohibits NGOs from using their own, non-U.S. funds to provide abortion services or information overseas. A mainstay of his campaign stump speech was that he’d cut federal funding to public schools that have vaccine mandates (which is…literally all of them, and that’s why you don’t have polio). And he’s said he has plans to revive a 2020 executive order called Schedule F that would allow certain federal employees to be fired at will (which, although scary, might be quite hard to enforce). OK, so: Does signing an executive order mean it’s automatically legal? Not quite. Many of these actions will be challenged in court, and in some cases subject to the (rather arcane) Federal Administrative Procedure Act. But besides determining policy, the sheer number of Trump’s Day One orders would set the tone for a more authoritarian era—and pose a test of the public’s ability to stay engaged in the face of chaos. With that in mind, some of these executive orders, especially the ones on immigration and trans rights, will have immediate impact on people’s lives. Stay tuned for more coverage next week. —Nona Willis Aronowitz AND:

WEEKEND READING 📚On survival: For months, people in Gaza were unable to purchase one thing their lives depended on: HIV medication. (The Intercept) On what children teach us: In this excerpt from an upcoming book she co-edited, Maya Schenwar tells the story of how motherhood changed her approach to prison abolition. (The Marshall Project) On killing the fact-checkers: What difference did the now-defunct Facebook research team actually make? Plenty, writes former fact checker Carrie Monahan in “Bare Facebook Liar.” (Air Mail)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

“You, Sir, Are a No-Go”

January 14, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, For anyone trying to get help while navigating the wildfires in California, we want to point you to this master document of resources, shelters, and distribution hubs created by Sarah Vitti and Bianca Wilson. And if you’re not in the LA area but you’re looking for ways to help, you can see what’s needed here. In today’s newsletter, we tune in to the Pete Hegseth hearing. Plus, some good news for Bad Bunny fans. With love, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONWhen politics and theater collide: Today was the Senate confirmation hearing for Pete Hegseth, who is auditioning to become our next Secretary of Defense on this week’s episode of America’s Next Top Menace. Now normally, a confirmation hearing for a drunken, underqualified, racist TV personality (who’s also an alleged rapist) would be incredibly high stakes. The kind of event that would rivet the nation, that I would halt my entire workday to watch. (In fact, we all did just that a few years ago.) But when you’ve already watched an underqualified, racist, former TV personality (who’s also an alleged rapist!) get elected president twice, you’re probably less likely to drop everything to watch history repeat itself on C-SPAN. And given the new GOP control of the Senate, today felt like a fruitless piece of political theater.  HEGSETH REACHING FOR A POINT TO MAKE AND FINDING NOTHING BUT AIR. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) But it was also necessary. True, the hearings may not prevent Hegseth from getting a job for which he has no aptitude. But if nothing else, the record will show that Hegseth stood in front of a group of senators who confronted him with his utter lack of leadership experience; the allegations of workplace misconduct, sexual assault, and financial mismanagement against him; and the “insufficient” FBI investigation of Hegseth ahead of his nomination. (According to the Washington Post, the FBI did not even interview the woman who accused him of sexual assault in 2017 as part of the vetting process. Sounds familiar.) Some of the harshest questioning came from women senators demanding that Hegseth answer for his “degrading” statements about women in the military. He chose to deny, saying, “I’ve never disparaged women serving in the military.” So to clarify: when he went on a podcast and said “we should not have women in combat roles” and when he wrote in his book “women cannot physically meet the same standards as men,” he didn’t say it in a degrading way. He was merely commenting on the lower standards the military has adopted in order to accommodate women! Sure, Jan. His comments on standards didn’t fly with Senator Tammy Duckworth, who is also a veteran—and, as a retired Lieutenant Colonel, outranks Hegseth. “You say you care about keeping our Armed Forces strong and that you like our Armed Forces' meritocracy,” she told Hegseth. “Then let's not lower the standards for you. You, sir, are a no-go at this station.” AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

How the LA Fires Got So Bad So Fast

January 13, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, The news from California has been heartbreaking; the Palisades, Eaton, and Hollywood Hills wildfires continue to sweep through the region, destroying entire neighborhoods, displacing thousands of people, and destroying wildlife. We hope all of our LA-based readers are keeping as safe as possible. For anyone looking for a way to help those affected by the fires, please take a look at this list compiled by Mutual Aid Los Angeles Network. In today’s newsletter, we piece together the connection between the California fires and climate change. Plus, your weekend reading list. With love, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONIn the line of fire: The Palisades and Eaton wildfires, along with a smaller fire in the Hollywood Hills, are being called “the most destructive” fires in the history of Los Angeles. So far, five people have been killed and roughly 180,000 people are under evacuation orders in the area. January isn’t peak fire season in California—so how did these particular fires get so bad so fast? The short answer is, for the most part, climate change. The longer answer is just how unseriously people in power are taking climate change. Experts have been saying for years that climate change would continue to exacerbate extreme weather events—hurricanes, fires, lightning storms, droughts, and wild weather swings. In California, those predictions have borne out: Climate change has contributed to hotter and drier weather, making for dangerous wildfire conditions. California’s famous Santa Ana winds are blowing with gusts as high as 100 mph. Add all of that to other consequences of climate change, such as recent dry weather and an “exceptionally wet climate from winter 2023 to spring 2024” (which created younger vegetation that isn’t as fire-resistant), and you have a region primed for a particularly bad fire season. There are other factors besides climate change, too: One scientist, UCLA professor Jon Keeley, told Mother Jones that power line failures, rapid population growth, and loss of fire-blocking vegetation in California have also played a large role in the fast spread of these fires. Finally, there’s California’s under-preparedness in the face of our new “pyrocene” era: There’s been a yearslong firefighter shortage in the state. As the blazes broke out this week, every single LAFD firefighter was asked to call in with their availability, a first in almost 20 years. (That includes those fire brigades composed of incarcerated people who get paid about 74 cents an hour for their labor.) All these factors have contributed to this week’s devastation in LA. What has not played a role are the city’s DEI initiatives—although that didn’t stop some right-wing pundits from claiming otherwise.The right is also placing blame on LAFD Fire Chief Kristin Crowley for prioritizing diverse hiring practices over “filling the fire hydrants properly.” (Just because it’s going to drive me crazy, I need to emphasize that it is not the fire chief’s job to fill the goddamn fire hydrants.) Activists often remind us that all of our struggles are interconnected. A fire in California does not exist in a vacuum; it lives in concert with a number of other political issues—none more so than climate change and how our leaders respond to it…or fail to do so. AND:

PRESIDENTS CLINTON, BUSH, OBAMA, TRUMP, AND BIDEN, ALONG WITH THEIR SPOUSES AND VICE PRESIDENTS GORE, PENCE, AND HARRIS AT THE FUNERAL SERVICE FOR PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

WEEKEND READING 📚On being the “other” mother: A woman who chose surrogacy reflects on the thorny relationship it created—and where it left them when tragedy struck. (Electric Literature) On justice deferred: A “horrendous” sexual assault trial in Alaska has been delayed more than 70 times in the last 10 years. Here’s how similar slowdowns have become routine in the state. (ProPublica) On “Mas Fotos”: Bad Bunny’s sixth album has become more than just an album. Julianne Escobedo Shepherd dives into the deeper meanings of the artist’s “textured love letter to Puerto Rico’s Indigenous and homegrown musical styles.” (Hearing Things)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

A Graceful Transition of Power

January 7, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, LOVE IS ALIVE! Tom Holland and Zendaya are engaged, and for reasons I can’t explain, I am happier for these two strangers than I have been for any of my real-life friends. But also none of my friends have gotten married to anyone as fascinating as Zendaya. Huzzah!  ZENDAYA CASUALLY TAKING HER NEW FIVE-CARAT ENGAGEMENT RING OUT FOR A STROLL. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) In today’s newsletter, we consider the subtle messaging around yesterday’s certification of the 2024 election. Plus, new rules for Meta and new music from Bad Bunny. Waiting for my wedding invitation, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONFull of grace: Yesterday, Vice President Kamala Harris presided over what was for generations a mundane congressional activity: certifying the vote. But this year had a different weight to it, and not because there was another insurrection. Instead, Harris had to hand the country over to white nationalists while rubbing salt in the wound of her own loss. She did so without fanfare or silent protest, with as much grace as anyone could muster, and she was largely praised for it. As Errin Haines wrote in The 19th, in certifying the vote, Harris “made history, this time as a linchpin in the work of restoring our shaken faith in the democratic process.” And while Harris’ handling of the moment is certainly a testament to her fortitude, it was also a reminder of the unmeetable expectations placed on Black women.  SHE ALMOST LET HERSELF FROWN FOR A MILLISECOND. BUT KAMALA HARRIS WILL NOT BE CAUGHT SLIPPIN'. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) People are angry. Women are angry. It is safe to assume that in private, Kamala Harris is angry. But were she to show that very human emotion in even the smallest way, it would undo everything she has worked toward. Kamala Harris doesn’t get to be angry because she has become the avatar for Black women in America in the same way that Barack Obama was an avatar for Black men (although he was allowed some anger, because that is an emotion men have the privilege to express, while Black women must studiously avoid the Angry Black Woman trope). Now this doesn’t mean I wanted her to walk into the chamber and start flipping desks. There is a time and place for decorum. But there’s almost always a way to peacefully fight back. Ask Nancy Pelosi, who in 2020 stood up after Donald Trump’s State of the Union address and tore a physical copy of his speech to pieces. Or Elizabeth Warren, who in 2017 refused to be silenced by her Republican colleagues. (That’s where all those “nevertheless, she persisted” t-shirts came from.) But the rules are and always have been different for the Kamala Harrises of the world, who have been instructed from day one that getting to the top requires a certain degree of “conceal, don’t feel.” For Black women, anger is not a tool that can be used to break the glass ceiling. Instead, their fight can only be composed of, in the approving words of Symone Sanders Townsend yesterday, “grace and grit.” Who is all that grace and grit serving, though? White onlookers? People invested in the status quo? If Black women are forced to conform to the expectation that they can only be gracious, even in the worst and most disheartening circumstances, it just reinforces an ugly but incredibly American idea that Black women must be made to feel small. Even in their own damn House. Yesterday, Kamala Harris provided a masterclass in moving forward even when what you’re walking toward is everything you stand against. And prioritizing the rule of law and the democratic process was, of course, the point: “Today, democracy stood,” she said afterward. Still, the message we should extract from that moment is not, grin and bear it. It’s: Do what you must to live to fight another day. Even if that includes getting angry. AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

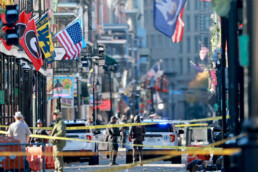

A Violent Start to the Year

January 2, 2025 Howdy, Meteor readers, Welcome back to the grind. I spent the entire holiday break trying to bake sourdough bread, watching videos about sourdough bread, and learning about microbakeries. I’ve pretty much joined a cult. And you?  ONE OF MY FAILED BUT AESTHETICALLY PLEASING LOAVES In today’s newsletter, we look at the common thread running through the mass violence of 2025’s earliest days. Plus, a huge power outage and another layer to the Baldoni/Lively situation. Bulk fermenting, Shannon Melerdough  WHAT'S GOING ONOff to a bad start: 2025 is only two days old but has already seen three mass violence events. Yesterday a veteran in New Orleans drove through a crowd of pedestrians, killing 15 people and injuring 30 more. Hours after that, in Las Vegas, a Green Beret driving a Tesla Cybertruck pulled up to the Trump International Hotel and allegedly triggered an explosion from within the vehicle, injuring seven and killing himself. Later that same night, in Queens, four men opened fire outside a nightclub, wounding ten bystanders, most of them women, in what appears to be an act of gang-related violence. Investigators do not currently have reason to believe the incidents are related; the FBI is calling the New Orleans killing an act of terrorism but has not designated the Las Vegas incident as such. But regardless of motivation, if these crimes weren’t what you talked about all day at work, it’s just another sign that violence in America is now considered something…normal. And as journalist Anand Giridharadas highlighted in his analysis of the events of January 1, one contributing factor we may not be taking seriously enough is the ease and speed with which men are becoming radicalized. In the New Orleans example specifically, the suspect was “inspired” by ISIS, and people who knew him say he had become withdrawn as he “descended into a rabbit hole of radicalization” and anger over the things that had gone awry in his life. (He also allegedly threatened violence against his ex-wife—another common thread among perpetrators of mass violence.) “Part of what makes the crisis facing men so dangerous is the fact that such radicalization pathways exist and are so easily accessible for men who find themselves in free-fall,” Giridharadas writes. “A whole lot of men are lost…and someone needs to figure out how to meet them where they are.” Unfortunately, as he notes, men are being met where they are—online, by violent and extremist movements that promise a return to virility and domination. And, as is evident by the Queens shooting, they’re being embraced by violent groups in real life as well. This theme—that men are being lured toward extremism—is not new, of course. Writers like Liz Plank, Jia Tolentino, and Jonathan Metzl voiced similar concerns throughout 2024 about what Tolentino calls “an era of gendered regression” fueled by ideological divides on things like masculinity, healthcare, gun rights, and bodily autonomy. But their work (and Giridharadas’s point) is a reminder that we can’t talk about these first bloody hours without talking about how men are being weaponized. How we start this year, though, does not have to be the way we continue it. Since we know solutions won’t be pouring out of the White House, let this be the year we dedicate to fortifying our communities and pushing for action. Support local organizations providing mental health to veterans or other at-risk groups. Push for gun reform in your city (and then for your state). Talk to the young men in your life about what they’re consuming online. We’ve got us. AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()