What activists knew when Roe was decided

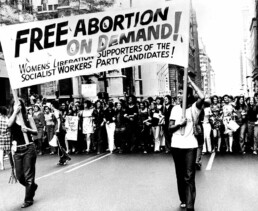

January 22, 2026 Hi, lovely Meteor readers, Today is one of my closest friends’ birthdays, a balm upon a far more bittersweet milestone: the 53rd anniversary of the Supreme Court’s now-overturned decision in Roe v. Wade. At least there’s birthday cake.  Today, we hear from early pro-choice activists on what it felt like that day when Roe was decided (hint: it’s complicated). Plus, some historic Oscar nominations and your weekend entertainment. Stuffing my face, Nona Willis Aronowitz  WHAT'S GOING ONHope and fear: Fifty-three years ago today, the Supreme Court handed down the Roe v. Wade decision. In a 7 to 2 vote, the justices struck down state abortion bans, replacing them with detailed national guidelines based on weeks of pregnancy. Bending to the groundswell of the women’s movement, four states—Alaska, Hawaii, New York, and Washington—had already repealed their abortion bans, and 13 others had expanded exceptions. But Roe made the right to abortion, based on the constitutional right to privacy, protected everywhere. What was that moment like for women active in the movement? In a post-Roe world, it’s easy to imagine that it was a day of unequivocal joy. I was curious, so I sought out some women who remember it clearly—and discovered that the truth is far more complicated. Yes, there was relief. Heather Booth, who’d started an underground abortion service called The Jane Collective eight years before when she was a student at the University of Chicago, remembers thinking: “FINALLY!” After nearly a decade of abortion advocacy, “the fear, hardship and danger for women who wanted to end an unwanted pregnancy would be addressed.” Dr. Wendy Chavkin, who’d occasionally lent the Janes her Chicago apartment and had organized travel for women to get abortions in New York, recalls the period after Roe as “heady days.” She and her fellow student activists felt “hope, determination and a big vision that saw links between gender and racial discrimination.” Shortly after the decision, she became a counselor at the first legal clinic in Detroit and eventually went to medical school to become an abortion provider herself.  WE GOTTA BRING BACK “FREE ABORTION ON DEMAND.” CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES But many feminists were wary of the meticulous pregnancy timetable the Supreme Court had laid out. “I saw it as a serious compromise,” says Carol Giardina, an early member of the women’s liberation movement in Gainesville, Florida, who recalls referring girls in her freshman dorm to abortionists back in 1963. Although the decision did represent “a mighty win for organized feminism-people power,” she says, her cohort had been “fighting like tigers for repeal of any and all laws on abortion.” That demand, remembers Alix Kates Shulman, radical feminist and author of Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen, sprung out of the worry that “any law would contain restrictions on full reproductive freedom and be vulnerable to constant attack. Which is precisely what happened.” Several women referred me to abortion activist and Redstockings member Lucinda Cisler’s 1970 essay in the feminist journal Notes From the Second Year. States were beginning to introduce laws that legalized abortion, but with exceptions—which, Cisler warned, “can buy off most middle-class women and make them believe things have really changed, while it leaves poor women to suffer and keeps us all saddled with abortion laws for many more years to come.” The only option, she argued, was total abolition of laws restricting abortion. And then there were the women who had other things on their minds. “I’m sorry to say I shrugged at Roe,” says Loretta Ross, who went on to be cofounder of SisterSong and one of 12 architects of the theory of reproductive justice, which encompasses far more than the right to abortion. In 1973, Ross was a teenage mother suffering from acute pelvic inflammatory disease as a result of the infamous Dalkon Shield IUD; instead of removing her IUD, a white, male OB/GYN misdiagnosed her for months until her fallopian tubes ruptured and she was forced to undergo sterilization. She’d had a “perfectly safe legal abortion” several years before in Washington, D.C.; “it wasn’t my lived experience to be denied.” So “while other people were celebrating Roe,” she recalls, “I was having the classic experience of a Black woman whose white doctor was deciding she doesn’t need to have any more kids.”  LORETTA ROSS IN 2022. CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES Although she wouldn’t read it until years later, Ross cited a 1973 editorial by the National Council of Negro Women’s Dorothy Height, who sounded a cautionary note about Roe v. Wade and its potential to worsen state control over Black women’s bodies: “We must be ever vigilant that what appears on the surface to be a step forward, does not in fact become yet another fetter or method of enslavement.” Ross’s sterilization led her to file (and win) a lawsuit against Dalkon Shield manufacturer A.H. Robins, and devote her life to bodily autonomy in all forms. If we don't “intersect race, class and gender,” Ross says, we’ll “never understand the full impact of Roe.” In our new landscape, after Dobbs, many activists are starting to come around to the idea that restrictions and exceptions have no place in abortion care. (They’ve succeeded in getting pro-choice states like New York, whose law goes further than Roe, to agree.) These early activists remind us that perhaps our north star shouldn’t be restoring Roe, but to wrest our reproductive justice out of the hands of politicians—and into our own. AND:

RUTH E. CARTER IN AN EXTREMELY TACTILE PIECE OF CLOTH. CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES

WEEKEND READING, WATCHING, AND LISTENING 📖 👁️ 🔊On a complex heroine: On the occasion of the Roe anniversary, I rewatched “AKA Jane Roe,” a documentary on the case’s plaintiff, Norma McCorvey…and seriously, wow. (FX) On cop-hating: A close read of an uncollected Joan Didion essay asks the question: What made her consign the piece to obscurity? (Dispatches) On heteropessimism: I am embarrassingly late to Heated Rivalry but maybe you are too, and would enjoy Tracy Clark-Flory and Amanda Montei discussing the show as an escape from heterosexuality. (Dire Straights)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Chrissy Teigen: "This is what care looks like"

Against a landscape of shrinking reproductive freedom, the TV personality and author visits a Tennessee clinic that offers both birth and abortion care

Tomorrow marks the 53rd anniversary of the Roe v. Wade decision. More than half a century later, in a country that no longer grants the freedom that that ruling declared, it’s easy to get mired in the onslaught of harrowing news about our bodies and our lives. But everywhere, there are warriors who keep doing the work of caring for pregnant people, and they are not mired. They are moving forward, every single day.

TV personality and best-selling cookbook author Chrissy Teigen has herself helped to humanize reproductive healthcare. She has spoken about her own experience having a lifesaving late-term abortion; visited the Feminist Center for Reproductive Liberation, a clinic in Georgia, in 2024; and then discussed her experiences with Vice President Kamala Harris during the 2024 presidential campaign. “I started crying once I saw this beautiful mural of butterflies above the operating suite” at the Feminist Center, Teigen told Harris at the time. A doctor there “looked me in the eye and she said, ‘You could have had butterflies.’”

Then, in 2025, The Meteor traveled to Tennessee with Teigen on another visit—one that shows that everyone deserves butterflies, and that you can’t talk about abortion care without talking about maternal care. CHOICES Center for Reproductive Health, a Memphis-based clinic, provides the full spectrum of care for people who can get pregnant. “All pregnancies are different,” says Jennifer Pepper, CEO and president of CHOICES. That’s why the center provides everything from midwife-assisted births to high-risk pregnancy care to prenatal classes—and, since abortion was banned in the state in 2022, abortions in their sister location three hours away in Carbondale, Illinois. (Pepper says CHOICES is the only nonprofit in the country where both birth and abortion take place. And after Dobbs, “we could not stomach the idea that [abortion] patients wouldn’t have anywhere to go,” she says.)

“Every single woman deserves that level of care in America,” Teigen says. “This is what care looks like—people listening to you, and treating your body and your choices with dignity.”

Teigen was moved by how the clinic felt so “open and welcoming and airy and light,” with a “sisterhood” that was far from “the coldness” of her own hospital experience. “It never crossed my mind that I could give birth on all fours, or be in a tub at a birthing center,” she said. She saw a better way to give abortion care, too. When Pepper told Teigen she got her start at CHOICES as an abortion doula, Teigen said, “I can’t tell you how much I would have appreciated an abortion doula,” someone to explain “what was happening with my body.”

Tennessee also has the highest rate of maternal mortality in the country—and so access to supportive birth care can mean the difference between life and death, particularly for Black women. One Black woman in the prenatal class, Jasmine, recalled a conversation with her doula at CHOICES that started with a heartbreaking wish—“First off, I don’t want to die”—and ended with her having a “beautiful experience” delivering her baby.

“Every single woman deserves that level of care in America,” Teigen says. “This is what care looks like—people listening to you, and treating your body and your choices with dignity.”

Producer/director/editor: Emily Murnane

Producer: Rachel Lieberman

Director of photography: Mary Gunning

Audio: Stacia Gulley

Production assistant: Dindie Donelson

Production assistant: Nola Madison

Post producer: Annie Venezia

Graphics: Bianca Alvarez

Produced with support from Pop Culture Collaborative, as part of the United States of Abortion series.

Are women really being “coerced” into abortions?

Greetings, Meteor readers,

It is bitter cold in much of the U.S. due to an Arctic blast, which seems like an appropriate way for Mother Nature to celebrate the first anniversary of Trump 2.0. Keep your fam and friends close this week (and for the next three years), because it’s near-uninhabitable out there.

Today, we’re teaming up with Jessica Valenti—friend of The Meteor and founder of Abortion, Every Day—on a fresh series of videos demystifying anti-abortion speak. Plus, a history-making governorship begins, and a little bit of justice for Tylenol.

Choosing coziness,

Nona Willis Aronowitz

WHAT'S GOING ON

Who’s coercing whom?: How does the term “coerced abortions” make you feel? Sounds horrible, right? Perhaps something an abusive parent or boyfriend would perpetrate against a vulnerable woman? The phrase—crafted to elicit this precise reaction—is the latest bit of lingo anti-abortion extremists are using to make Americans think that abortion hurts women. If it sounds familiar, you may have encountered it in Republican talking points, lawsuits and state laws—or heard conservatives like Sen. Bill Cassidy (R.-La.) and Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill mention it just last week during a Senate hearing meant to discredit abortion pills. The pills, Cassidy claimed, go “straight to [an abuser’s] mailbox, no questions asked, and then they coerce the woman to take it … Think of the women, the girls in abusive relationships, being trafficked whose voice is being silent.”

OME ANTI-CHOICE PROTESTERS IN 2022 WIELDING THE LANGUAGE OF COERCION. (CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES)

Again: Sounds awful. But in a new edition of our series Anti-Abortion Glossary—in which Abortion, Every Day’s Jessica Valenti unpacks the misleading, misogynist terms used by the anti-abortion movement—Valenti explains that this kind of rhetoric is being specifically used to target doctors who provide abortion medication, or, as in one Louisiana case, a mother who helped her teenage daughter obtain abortion care.

To be clear, some abusers absolutely do force their partners to end a pregnancy. But in a post-Roe world, it is vastly more common that women will be coerced into continuing a pregnancy—either by an abusive partner, or, in the case of abortion bans, by the state itself. In fact, a study from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that abortion bans worsen intimate partner violence by as much as 10 percent. And sometimes, the government helps: in one case out of Texas, police used 83,000 cameras to track down an abortion patient because her abuser turned her in.

So why are conservatives so obsessed with “abortion coercion” when forced pregnancy is a far greater problem? Valenti’s reporting found that in 2023, anti-abortion leaders pinpointed “coercion” as their most effective tool to justify abortion bans—which, after all, are deeply unpopular with most Americans. “The new Republican message must be clear. No woman should ever be subjected to an unwanted abortion,” advised David Reardon of Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America in an opinion piece for The Hill. Valenti sees right through this strategy. “They figured that pretending to care about coercion might make it seem like their laws are protecting women,” Valenti says. “They’re not.”

New episodes of Anti-Abortion Glossary will be dropping every Tuesday on Instagram. Watch here:

AND:

- Speaking of Arctic blasts: Thousands of Greenlanders (a number that constitutes a major chunk of the country’s population) marched in the streets on Saturday to protest Trump’s threat of invading the country. Among the protesters was Tillie Martinussen, a former member of parliament, who’s called the U.S. “greedy” and accused Trump of surrounding himself with “white power people.” The American government “started out as sort of touting themselves as [Greenland’s] friends and allies,” she told EuroNews at the protest. "And now they're just plain out threatening us.”

GREENLANDERS TURNED OUT ON SATURDAY AGAINST TRUMP’S IMPERIALIST PLANS. (CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES)

- Speaking of Arctic blasts: Thousands of Greenlanders (a number that constitutes a major chunk of the country’s population) marched in the streets on Saturday to protest Trump’s threat of invading the country. Among the protesters was Tillie Martinussen, a former member of parliament, who’s called the U.S. “greedy” and accused Trump of surrounding himself with “white power people.” The American government “started out as sort of touting themselves as [Greenland’s] friends and allies,” she told EuroNews at the protest. "And now they're just plain out threatening us.”

- Virginia’s first woman governor, Democrat and former CIA officer Abigail Spanberger, was sworn in on Saturday, and she made it her first order of business to repeal her predecessor’s order to cooperate with ICE. “We will focus on the security and safety of all our neighbors,” she promised in her inauguration speech. “And in Virginia, our hardworking, law abiding immigrant neighbors will know that…we mean them, too.” Also sworn in: Ghazala Hashmi, Spanberger’s lieutenant governor, who’s the first Muslim woman ever elected to state office.

- A new scientific study published in the medical journal The Lancet should reassure pregnant women that they need not “tough it out,” as our esteemed president

andTrump recently advised: In a review of more than three dozen studies, the researchers found no link between acetaminophen use during pregnancy and autism.maternal health expert - There’s no such thing as too much Magic Mike, as New Yorkers will soon discover.

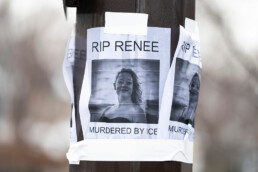

- Heads up: a new epithet is spreading on the far-right to describe Renee Good and those close to her. Think we’ll take “organized gangs of wine moms,” please and thank you.

- Still pissed? Allow us to suggest a rage room.

- Prefer to be anesthetized instead? Subscribe to Collier Meyerson’s new Substack, Soothe Operator, a place to “look away from the sun, briefly,” because “it’s important to go soft in order to go even harder.”

The nurses will not back down

NEWS

January 15, 2026 Hi there, Meteor readers, The 2016 nostalgia dominating my social feeds has me in my feelings today. I’m thinking about all the protests that year, now overshadowed by the acute tragedy of Donald Trump’s victory that fall. In America, there were the Black Lives Matter marches condemning the murders of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, and the students who took to the streets after Stanford rapist Brock Turner’s lighter-than-air sentencing. Overseas, there were the Black Monday strikes in Poland against proposed abortion bans, anti-corruption demonstrations in Brazil, and millions-deep marches following Brexit. Maybe it’s because I was younger, or because I’d been lulled by the dulcet tones of Obama’s rhetoric, but my sense of indignation was fresher back then. Hotter. More vivid. This week, as the powers that be attempt to quash dissent both here and abroad, I’m channeling that energy anew.  Today, Meteor contributor Ann Vettikkal brings us a dispatch from the historic nurse’s strike in New York City. Plus, a tribute to an unsung civil rights hero, and your weekend reading. 2016 on the scene, Nona Willis Aronowitz  WHAT’S GOING ON“We’re here for our safety”: “What do we want? A fair contract! When do we want it? Now!” This past Tuesday morning, a sea of demonstrators in red surrounded Columbia University Irving Medical Center demanding a fair contract prioritizing patient and nurse safety. They chanted and struck cowbells; one sign read, “Staffing so unsafe, Florence Nightingale is rolling in her grave.” Shows of solidarity in the form of honks, cheers, and salsa music echoed throughout Washington Heights.  NURSES INVOKING THE GOAT, FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE. CREDIT: GETTY IMAGESThe largest nurses’ strike in New York City’s history has now entered its fourth day. On Monday morning, nearly 15,000 nurses walked out of the Montefiore Medical Center and multiple hospitals in the New York-Presbyterian and Mount Sinai Health System network. The nurse’s union, New York State Nurses Association, says management refuses to budge on key issues. (“Here’s a pebble, here’s a little grain of salt” is how one nurse characterized management’s response.) The union says the strike is focused on protecting nurses’ healthcare benefits, safeguards against workplace violence, and safe staffing mandates, which ensures enough nurses are scheduled each day to deliver safe, quality patient care. Joe Solmonese, a spokesperson for Montefiore Medical Center, called their requests “reckless”; a statement from Mount Sinai said NYSNA refused to “move on from its extreme economic demands” for significant pay raises. “The hospitals take advantage [of the fact] that we are the ones that actually care about our patients,” said Beth Loudin, a pediatric nurse and president of the bargaining unit at New York-Presbyterian, who was picketing on Tuesday. “They don’t think we would go outside and fight for the things that actually protect us and protect our patients.”  BETH LOUDIN AT THE PICKET LINE. CREDIT: ANN VETTIKKALLoudin became a nurse a decade ago because of her passion for listening and advocating for people in difficult times. She joined the union four years ago and eventually rose to leadership. She pointed to the gains a smaller nurses’ strike involving Mount Sinai and Montefiore won three years ago—which included hiring additional nurses, and implementing minimum nurse-to-patient ratios—as a precedent for this “historic” strike. There are plans to head back to the negotiation table this evening, according to a NYSNA statement released this morning. In addition to their original demands, NYSNA charges that Mount Sinai “unlawfully terminated” and disciplined several outspoken nurses in the days leading up to the strike. Several politicians have shown their support, including Mayor Zohran Mamdani, who joined the picket and donned a red NYSNA scarf on the first day of the strike. “These nurses are here for New Yorkers,” Mamdani said in a statement to the press. “They show up and all they are asking for in return is dignity, respect, and the fair pay and treatment that they deserve.” This strike comes on the heels of many other nurses’ strikes across the country. Given that nursing is the number one occupation for women, these fights could meaningfully move the needle on the overall quality of life for women in this country. “It’s now a wave,” Loudin said. “We’re here for the patients. We’re here for our safety. I hope that wave just continues to grow and grow and grow.” —Ann Vettikkal AND:

CLAUDETTE COLVIN IN 1998. CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES

WEEKEND READING AND LISTENING 📚 🔊On systemic racism: Why this Texas county is the deadliest place for Black mothers to have a baby. (Capital B) On frenemies: Dayna Tortorici untangles the many divisions that have torn feminists apart for 200 years. (n +1) On “the last American dream”: Please enjoy this exceedingly delightful interview with comedian Robby Hoffman on masculinity, her Hasidic upbringing, and rich-people guilt. (Talk Easy with Sam Fragoso)

|

![]()

Courage and cigarettes

NEWS

January 15, 2026 Greetings, Meteor readers, My kid is getting her tonsils taken out this week. Any parents out there with tips on how to survive the recovery period, I welcome the guidance. On to bigger things. In today’s newsletter, protests in Iran have already reached a terrifying death count. Plus, the government is investigating Renee Nicole Good’s widow instead of focusing on her killer. Popsicles for the apocalypse, Shannon Melero  WHAT’S GOING ONA history of resilience: At the end of December, shopkeepers and business owners in Tehran shut down their stores and took to the streets in protest. Within hours, a chant at the heart of the protest had spread across the city: “Our money is worth less.” What began as a localized economic complaint has grown into a nationwide anti-government protest that has reportedly claimed the lives of thousands of Iranians. To outside observers—especially those of us caught up in our own country’s headlines—this was a startling escalation. But for those living and working in Tehran, the writing was on the wall for some time. The Iranian economy has been in crisis mode for months: sanctions from the U.S., a 12-day war with Israel, water shortages, and in December—apparently the last straw—Iran’s currency, the rial, hit an all-time low. In an initial response to the protests, the Iranian government offered a monthly stipend to alleviate financial woes that was equivalent to seven U.S. dollars. It was an insulting band-aid. And as protests continue, Iran’s leaders have resorted to suppression and violence, attempting to keep Iranians quiet with internet blackouts, imprisonment, and murder by officials of the regime. And while all Iranians are suffering as a result of economic and political instability, this is yet another situation in which women will suffer the most. A UN Women report from 2024 found that Iranian women are more than twice as likely to be unemployed as men. In times of political upheaval, those numbers—along with sexual and physical violence against women—are expected to worsen. We have all seen this before. Time after time, the Iranian people have risen up against their leaders despite being met with the cruelest response. In 2022, after the killing of Mahsa Amini, which sparked the Woman, Life, Freedom movement. In 2021, over water shortages. In 2019, over fuel prices. In 2009, over questionable election results. But some Iranians who spoke to the New York Times said that these protests felt more powerful than even those of 2022 because they have captured Iranians from all walks of life. Young women have been front and center; the internet is full of images of Iranian women using burning pictures of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to light their cigarettes. Conservative and rural Iranians—who for the most part remained on the sidelines during the Women, Life, Freedom movement—are making themselves heard now. “We can see from the news and from some government reactions that this regime is terrified to its bones,” one protester in Tehran told a Times reporter. Many in the streets, on the other hand, are projecting fearlessness. “We are not afraid,” said Sarira Karimi, a University of Tehran student who was arrested last month, “because we are together.” The Trump administration has been keeping an eye on the situation, and earlier today, the president suggested that he was open to an airstrike, writing on Truth Social that the U.S. was “locked and loaded” and that “help was on the way” for protesters (excuse us?). He added that the military was reviewing “some very strong options.” No mention yet if Trump intends to be the acting president of both Venezuela and Iran, but it wouldn’t surprise anyone. AND:

PROTESTORS IN MINNEAPOLIS THE DAY AFTER GOOD’S MURDER (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

OF COURSE THE GAY SHEEP ARE SERVING LOOKS TO THE CAMERA (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Renee Nicole, and Keith, and Marimar, and...

January 9, 2026 Hey there, Meteor readers, Anyone else already getting impatient waiting for Heated Rivalry, Season Two? We NEED to get back to the cottage.  In today’s newsletter, we look at the story that’s on all our minds today—the murder of Renee Nicole Good—and the long road of violence that preceded it. Plus, a moment of good news for parents, and your weekend reading list. One day at a time, The Meteor Team  WHAT'S GOING ONA growing list of names: Yesterday, a masked ICE agent in Minneapolis shot and killed Renee Nicole Good, who had allegedly been blocking agents from entering her neighborhood. Shortly after the shooting, a Department of Homeland Security spokesperson referred to Good as a “violent rioter” and called the killing an act of self-defense. DHS Secretary Kristi Noem even suggested that Good was part of a group carrying out a “domestic act of terrorism” using vehicles as weapons. But video from the scene shows Good giving way to federal vehicles and trying to respond to conflicting orders from DHS agents, shortly before she was approached and shot through her windshield. Witnesses to the murder have also contradicted DHS’s account of what happened, and video also appears to show ICE preventing medical personnel from nearing the scene. Good’s murder has sparked protests in Minneapolis and calls for investigations into ICE’s tactics. Renee Nicole Good was a parent. Just like Keith Porter, who was shot and killed by an off-duty ICE officer in December for reportedly not complying with an order. Renee Nicole Good had a life, a family, a job. Just like Silverio Villegas Gonzalez, who was shot and killed by ICE agents during a traffic stop in September. Renee Nicole Good was sitting in her car, just like Marimar Martinez, a teaching assistant in Chicago who was shot five times by ICE agents in October. (Miraculously, Martinez survived.) Renee Nicole Good’s community was being terrorized by a violent group of thugs hiding behind masks and the emblem of a federal agency—just like communities in Boyle Heights, Westlake, Santa Ana, Pasadena, and Chicago. And that’s not even to speak of what happens where videos rarely record: In 2025, 32 people died while in ICE custody—the most in more than two decades. Movements in America often gain traction after a horrific event spurs people into action. The violence has to be so profound, so unbearable, or so vividly recorded to shake us from a passive state. But those boiling points are never the first incidents. Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi launched Black Lives Matter back in 2013, after the man who killed Trayvon Martin was acquitted—seven years before the murder of George Floyd sparked massive protests across the country. Tarana Burke amplified stories of sexual assault and harassment for more than a decade before reporters exposed Harvey Weinstein’s crimes and MeToo went viral. The question I find myself asking is: Will Renee Nicole Good be the one? Will her murder be the turning point for us to stay in the streets, for judges to intervene, for any lawmaker still waffling to decide “no more”? Or will she blend in with the rest of the violence? A month from now, will we forget her name as we’ve forgotten Keith, Silverio, Marimar, and the dozens of others who never had their moment in the national news spotlight? How much does the body count have to rise for every last person to flood the streets for justice? Because it must be all of us. Our elected leaders are not equipped to take on this task alone. Rep. Ayanna Pressley made her stand and demanded an investigation into the killing of Renee Nicole Good; the GOP blocked it. Former Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot is launching an ICE Accountability Project, which is a step in the right direction, and Rep. Robin Kelly is filing articles of impeachment against DHS Secretary Kristi Noem. But between 2015 and 2021, ICE agents were involved in 23 fatal shootings. No agents were indicted. Will this be the year we stop at one? AND:

A POSTCARD FROM MAMDANISTAN 😘 (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

WEEKEND READING 📚On history: On the heels of a protester’s violent death at the hands of law enforcement, it might be useful to reread Jill Lepore’s 2020 piece on whether we still recall the lessons learned in blood at Kent State. (The New Yorker) On healing: There are glimmers of hope for the uninsured in America. (The Baffler) On heroes: To celebrate Wyoming’s recent abortion win, here’s a profile of Julie Burkhart, an unstoppable abortion care provider in the state. Even an arsonist burning down her clinic wasn’t enough to slow her down. (The Story Exchange)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Tears, Joy, and Fear

January 7, 2026 Salutations, Meteor readers, Happy New Year, friends, it’s good to see you all again. We hope you had a lovely stretch of time off from the real world and are ready to jump back into the massive amounts of everything going on. In today’s newsletter, one of our colleagues shares a personal reflection on what this past week has been like as a Venezuelan living in the United States. Plus, we mourn the loss of a maternal health advocate. Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON

I'm Anti-Trump and Venezuelan. This Week Has Been ComplicatedMy heart is celebrating while my brain sees the bigger picture. MADURO AND HIS WIFE ON THEIR WAY TO A FEDERAL COURTHOUSE IN NEW YORK. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) On January 3rd, the U.S. seized Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife in a military operation that shocked the world. The reaction from many Americans, who have lived through this playbook before, was outrage. The arrest of Maduro and his arraignment in New York courts has been perceived as an attempted regime change, a violation of international law, and an oil grab—all of which, to be clear, it is. (And there’s probably more madness ahead, given Trump’s comments about how “we need Greenland.”) So what does it all feel like for Venezuelans? After Trump declared that he plans to “run” Venezuela, many are fearing for their safety. At the same time, some Venezuelans in the United States are celebrating the removal of an oppressive dictator from power. For our colleague Bianca—a progressive Venezuelan living in the U.S., who asked that we withhold her last name due to privacy concerns—the moment was quite complex. Here’s what the last few days have been like for her. I'm 100 percent Venezuelan, born in Caracas. I grew up going to El Ávila National Park and the beaches of Margarita Island and just enjoying my country. But when [former president] Hugo Chavez got into power in 1998, the whole country was sort of panicking because of the authoritarian policies. Protests started. Repression and political polarization got gradually worse. Friends and family were put in jail simply for expressing their views. By 2007 or so, media suppression intensified; If The Meteor were in Venezuela, everybody [working here] would be in jail. I was part of the first wave of Venezuelans who left, although much of my family stayed. When I got to Miami in 2001, when I was 21, I totally disconnected from my Venezuelan life. For a decade, I just felt like “I don’t want to deal with this”—kind of what people are doing now in the U.S. It was too much and too painful. Then the 2014 protests happened [sparked by an attempted rape of a student in San Cristobal]. The government was killing students in the streets. That’s when I decided to go to Venezuela with my camera, so I could document the reality of what was happening. Public opinion in the U.S. seemed to frame the student protesters as privileged Republicans. When I started interviewing these students, I discovered that was not true. I met kids from the slums of Venezuela, 15 or 16 years old, narrating their torture incidents in prison. I realized it wasn't a left versus right thing–it was a human rights thing. VENEZUELANS OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED NATIONS OFFICE IN CARACAS DURING THE 2014 PROTESTS. (PHOTO BY BIANCA) These kids were just begging the UN to come help, and they never did. After that, I came back to the U.S. and dedicated myself to social justice. I am a Democrat who is against authoritarian regimes, unfair elections, media censorship, and political repression. I've lost [Venezuelan] friends and family because I was a Bernie supporter, and they cannot believe how I can support Bernie as a socialist [because Chavez and his successor Nicolás Maduro were socialist]. Which was why it felt weird to see Trump’s tweet about how Maduro had been captured. Trump’s tweets usually have a horrible, disgusting effect on my heart, but this is the one time a Trump tweet made me incredibly happy. I woke up my mom and gave her the biggest hug and we both started crying. It finally felt like a little bit of justice. I can see why other left-leaning people in the U.S. are scared that this is going to become another Iraq–especially coming from Trump. I saw what happened with Afghanistan and Iraq, and I was against all of it. But I am disappointed to see my flag being used to push agendas; I’ve seen non-Venezuelan protesters [in the U.S.] with Venezuelan flags holding signs saying “Free Maduro.” And we have been screaming for help for years. Some of the arguments [point out that] this violates international law. Okay, but where was the international law when we were asking the UN to come, or when [Maduro] stole the election from us last year, or when they were massacring kids? Where was the international law when we were asking for so much? BIANCA IN 2014 WITH A PROTESTOR WHO WAS IMPRISONED UNDER THE MADURO REGIME. (PHOTO BY BIANCA) We are in a moment where we have to learn how to hold two opposing truths at once. My heart is celebrating while my brain is carefully thinking through the bigger picture. We deserve this joy after so many years. But there is much more to do to re-establish democracy in my country, and I’d be shocked if Trump were the person to do it. —as told to Nona Willis Aronowitz  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

The Essential Stories of the Year

|

Happy holidays, Meteor readers, If we had to pick a single phrase to describe this last year, it would be A LOT. All caps very necessary. A lot happened, a lot changed, and a lot of people lost everything. It was a lot of year. But there was also a lot of great reporting, much of it by women. Despite the attacks on journalists, the doxxing, the name-calling—the “quiet, piggy” of it all—women reporters have been getting it done. So for our final newsletter of 2025, we revisit the pieces that informed us (and the world), changed our perspectives, or even just made us laugh when we really needed it. We’re grateful for the work of our peers and for all of you. (And if you want to support the work we do, it’s easy!) Catch you on the flip, Nona, Cindi, and Shannon  It is no easy task to bring data to life—especially when the state has stopped collecting it. But Andrea Suozzo, Sophie Chou, and Lizzie Presser did exactly that in this essential investigative series, which revealed the extent to which Texas’s abortion ban has increased rates of sepsis and, in some cases, killed women. One of the biggest stories of this year—the arrest and attempted deportation of Palestinian activist Mahmoud Khalil—was broken in March by an all-woman team of students at the Columbia Spectator. Tsehai Alfred, Surina Venkat, Daksha Pillai, Miranda Lu, and Aiyana St. Hilaire not only were the first to report Khalil’s wrongful arrest, they also took their university to task for being complicit in it. The Eyes of Gaza

|

|

![]()

What to Do After a Dark Day

December 16, 2025 Greetings Meteor readers, I’m typing to you all from beneath a pile of assorted doughs as I made the terrible error of deciding to gift mini cookie boxes this holiday season. Please send help. And more butter if you’ve got it. In today’s newsletter, we look at two polar-opposite responses to similar tragedies, mourn the death of a true feminist, and celebrate the birth of a literary icon. Plus, one year after the end of civil war in Syria, journalist Tara Kangarlou speaks to women who have returned home to rebuild their lives. C is for cookie, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONThere’s a better way: This week, on opposite sides of the world, two horrifying acts of violence took place. On Saturday, a gunman killed two people at Brown University. The following day, news broke that two gunmen in Australia had killed 15 people gathered for a Hanukkah celebration at Bondi Beach. This year in America, there were 17 school shootings and 392 mass shooting events. This year in Australia, there was a grand total of one mass shooting event—this one. It’s the country’s first since 2018 and its deadliest in almost three decades. In the hours following the Brown University shooting, the Trump administration circulated misinformation and told reporters, before he even offered condolences, “Things can happen.” Following the Bondi Beach tragedy, the Australian Prime Minister, Anthony Albanese, promised to make the existing gun laws even stricter, saying, “The government is prepared to take whatever action is necessary.” Several new measures have already been proposed by Albanese and other members of his government, including limiting the number of guns an individual can own. Australia has been here before: After that deadly shooting 28 years ago—in Port Arthur—Australia passed some of the strictest gun laws in the world, including a national buyback program. Other countries like Norway, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand (whose prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, explicitly cited Australia as an inspiration) have reacted similarly to mass shootings. But not here—not yet. Granted, there's no panacea for any of this. Gun violence will never be entirely preventable; we know this from basic statistics. Even with its strict laws, Australia had 31 gun homicides last year. But that is .21 percent of the U.S.’s 15,000. In the wake of a very bloody weekend, it’s comforting to remember that some leaders and governments have swift, appropriate responses to horrific violence. And that there's absolutely no reason why we couldn't, too. AND:

ROB AND MICHELE EARLIER THIS YEAR (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

MOTHER. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

Syria’s Mothers are Fighting to Rebuild Their HomesBY TARA KANGARLOU One year after the end of a long war, they describe what coming home has really been like.KANGARLOU AND LANA, A 35-YEAR-OLD MOTHER FROM SYRIA'S ZABADANI REGION STANDS IN THE RUINS OF WHAT WAS ONCE HER FAMILY HOME. (COURTESY OF KANGARLOU) “There are very few mothers here who haven’t lost a child or a spouse, and very few children who haven’t lost a mother or a wife,” says 62-year-old Khadijah as she sits on the floor of a heavily bombed building—flattened, except for the one room where she now lives with her 75-year-old husband, Khaled. Like most of her neighbors, Khadijah, her husband, and her children—previously displaced across Syria and neighboring Lebanon and Turkey—are now returning to their devastated hometown of Zabadani, wondering how to pick up fragments of a life uprooted. The nearly 13-year war in Syria is known as one of the worst humanitarian crises of the 21st century. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the conflict displaced more than 13 million Syrians, six million of whom fled to neighboring countries. For years, the war functionally dismantled the country’s healthcare and infrastructure and robbed an entire generation of children of their childhood and education—losses that ripple through every fabric of Syrian society today. The UN Human Rights Office has documented over 300,000 civilian deaths, with some estimates approaching half a million. Multiple mass graves have been found across the country, and President Bashar al-Assad’s deployment of chemical weapons in Ghouta and Duma against his own people marked the deadliest use of such agents in decades. This month marks a year since the fall of al-Assad, and over that time, millions of Syrians have been adjusting to their newly liberated reality. More than four million have made their way back to their villages across Syria—their homes reshaped by years of siege, bombardment, and civil war. In Zabadani, Eastern Ghouta, Madaya, Duma, and other hard-hit regions across the country, mothers—like Khadijah—are navigating these losses firsthand as they work to restore a semblance of stability for their families. DESTROYED STRUCTURES SERVE AS DAILY REMINDERS OF CIVIL WAR ACROSS SYRIA. (PHOTO COURTESY OF TARA KANGARLOU) It should be a time of celebration, but for those living among the remnants of destruction, grief is pervasive. “Before the war, I would always wear white, but ever since the first death in our family, I’ve not taken off my black scarf,” Khadijah says. “I continue to be in mourning,”  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Syria's Mothers are Fighting to Rebuild Their Homes

One year after the end of a long war, they tell journalist Tara Kangarlou what coming home has really been like

By Tara Kangarlou

“There are very few mothers here who haven’t lost a child or a spouse, and very few children who haven’t lost a mother or a wife,” says 62-year-old Khadijah as she sits on the floor of a heavily bombed building—flattened, except for the one room where she now lives with her 75-year-old husband, Khaled. Like most of her neighbors, Khadijah, her husband, and her children—previously displaced across Syria and neighboring Lebanon and Turkey—are now returning to their devastated hometown of Zabadani, wondering how to pick up fragments of a life uprooted.

The nearly 13-year-long war in Syria is known as one of the worst humanitarian crises of the 21st century. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the conflict displaced more than 13 million Syrians, including the six million people who fled to neighboring countries. For years, the war functionally dismantled the country’s healthcare and infrastructure and robbed an entire generation of school-aged children of their childhood and education—losses that ripple through every fabric of Syrian society today. The UN Human Rights Office has documented over 300,000 civilian deaths, with some estimates approaching half a million. Multiple mass graves have been found across the country, and Bashar al-Assad’s deployment of chemical weapons in Ghouta and Duma against his own people marked the deadliest use of such agents in decades.

This month marks a year since the fall of Bashar al-Assad, and over that time, millions of Syrians have been adjusting to their newly liberated reality. More than four million have made their way back to their villages across Syria—their homes reshaped by years of siege, bombardment, and civil war. In Zabadani, Eastern Ghouta, Madaya, Duma, and other hard-hit regions across the country, mothers—like Khadijah—are navigating these losses firsthand as they work to restore a semblance of stability for their families.

It should be a time of celebration, but for those living among the remnants of destruction, grief is pervasive. “Before the war, I would always wear white, but ever since the first death in our family, I’ve not taken off my black scarf,” Khadijah says. “I continue to be in mourning,”

Like so many others in Syria’s Zabadani region, Khadijah and her family hail from generations of experienced, hard-working farmers. But the land, once celebrated for its apple orchards, vineyards, and lush farmland that helped feed Damascus, endured one of Syria’s longest and most punishing sieges. Between 2015 and 2017, barrel bombs, airstrikes, and artillery shells rained down, destroying irrigation systems, flattening farmland, and contaminating the earth with heavy metals, TNT, and fuel residues. The blockade also choked off agricultural inputs—seeds, fertilizers, and clean water, leading to the collapse of a once-thriving rural economy.

“We’d feed an entire town with our fruits and vegetables, but now, we barely have enough to feed our own family,” says Khadijah, whose grievances are evident when you visit her farm, where the soil is depleted and infrastructure destroyed.

“The only people whose farmland was spared were the people who cooperated with the Assad regime,” Khadijah explains. “We’re grateful to be alive, and we will rebuild, even though right now, we just don’t know how.” Later, she recalls the harrowing days in 2015 when she, her two daughters, and her then two-year-old grandson, Ammar, were displaced to nearby Madaya as the Assad army besieged Zabadani. Soon, those under siege in Madaya were facing severe food shortages and starvation under a blockade imposed by Assad’s forces and his allies Russia and Iran-backed Hezbollah.

“Ammar’s father [my son-in-law] was just killed…when we were forcefully moved to Madaya,” she says. “We had so much grief. “For the nearly two years that followed, we had nothing to survive on except rationed sugar, bread, and at times animal feed and grass.”

It wasn’t until 2017, following months of siege, that Khadijah and her family were relocated to opposition-held Idlib where they continued to live in displacement with little means to support the family.

Now 22, Ammar is studying to be a medical technician in Idlib—a city that remained the only lifeline for hundreds of thousands of displaced Syrians during the war. Visiting his grandparents in Zabadani, he brings in freshly made Arabic coffee and sits next to his grandmother and 37-year-old uncle Omar, who lost an eye in the war. Both men look at Khadijah with deep respect and endearment. “Every single mother in Syria has suffered tremendously, including my own mother and my grandmother; but we are of this land, and we’re happy to be back,” said Ammar.

The Flowers Still Bloom

Across Syria, the devastating impact of warfare is as environmental as it is emotional.

Just an hour’s drive from Damascus, 35-year-old Hiba walks through her hometown of Duma in Eastern Ghouta, stopping at a perfume shop to buy rose-scented oils—a defiant joy after surviving years of siege, bombardment, and chemical attacks. “Everything above ground was destroyed,” she says, recalling giving birth during the war in a half-collapsed clinic with no medicine, water, or electricity. Today, Hiba calls her 7-year-old daughter, Sally, her best friend and the person who makes life meaningful. “She loves riding her scooter and wants to be a pharmacist,” Hiba shares.

During the war, inspired by her family’s struggles caring for her younger brother with Down syndrome, Hiba began working with children with special needs—a profession she continues to this day, despite her own personal battles.

“People were disconnected from the world,” she says, pointing to what once was her house—a collapsed building lying under the weight of repeated barrel bombs and artillery strikes. “Our country is destroyed, but we mustn’t forget what happened to us. Our children must remember everything—so it doesn’t happen again.”

Both Zabadani and the Eastern Ghouta regions stand as stark evidence of how siege warfare and chemical weapons became tools of collective punishment—obliterating not just lives, but the ecosystems and livelihoods that sustained millions of ordinary civilians, including mothers, who are now searching for hope amidst rubble.

Back in Zabadani, 35-year-old Lana—a mother of two toddler boys—walks the grounds of her grandfather’s house and what was once her safe haven as a child.. She is a psychologist who has recently returned to her flattened town after years of life as a refugee in Lebanon. Today, along with her husband, she’s back “home,” doing what she once dreamed of doing for her own people and community.

“This is my grandfather’s home. My daddy grew up here,” she says. “We used to play here as children.”

The building’s walls are pocked with shrapnel holes and its ceilings blown down into rubble, but as we climb up and walk into the remnants of the house, she suddenly turns around, tearing up. On a half-collapsed wall, a faint drawing survives—painted decades ago by Lana’s father as a child, and depicting a red house surrounded by trees and a bright blue lake—the last fragile trace of a family’s life before war.

“My daddy was an artist. I have to tell him this is still here.” She looks at the flowers growing from underneath a pile of stones and smiles: “See, even in the middle of this destruction, we still have flowers bloom. There is hope, Tara. We are here.”

Tara Kangarlou is an award-winning Iranian-American global affairs journalist who has produced, written, and reported for NBC-LA, CNN, CNN International, and Al Jazeera America. She is the author of The Heartbeat of Iran, an Adjunct Professor at Georgetown University, and founder of the NGO Art of Hope.