Min Jin Lee on Justice for Asian Americans

By Samhita Mukhopadhyay

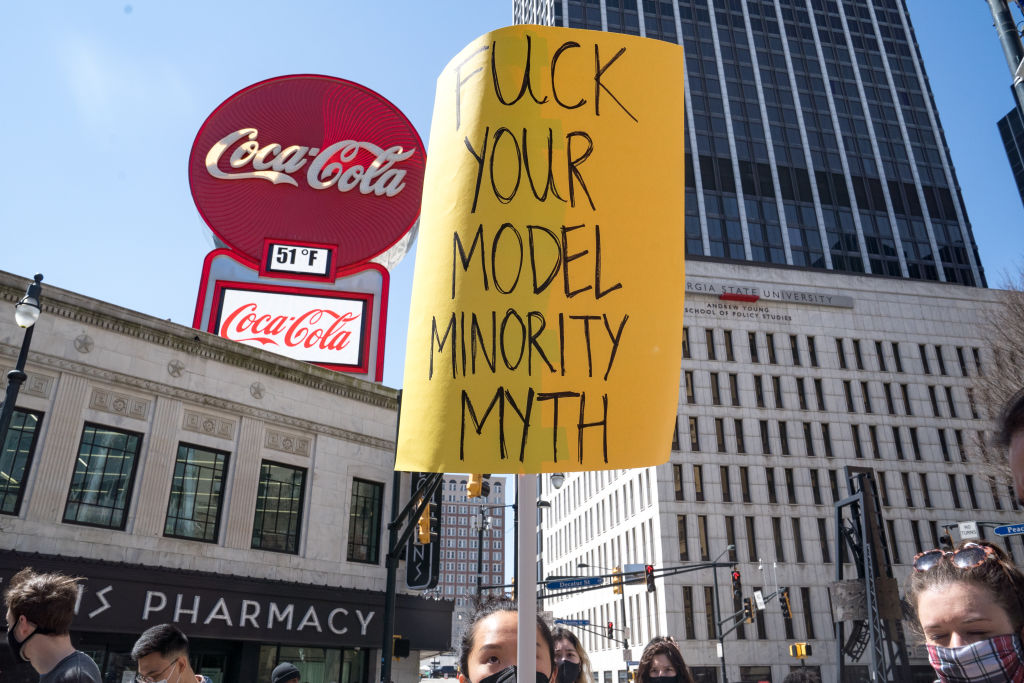

Min Jin Lee has been sounding the alarm on the startling rise of anti-Asian violence for the last few years. And the award-winning author has been unapologetically “extra Asian” lately. In March of this year, on the one-year anniversary of the tragic shooting at a spa in Atlanta where eight people (six of them Asian women) were killed, Lee helped organize a nationwide #BreaktheSilence action demanding justice for Asian women. Through tears, she addressed the rally in Times Square: ”We have read the data, but I want to know how you are doing in light of such dismal and terrifying hate?”

The data paints a grim picture: the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism found that anti-Asian hate crimes were up 339% in 2021. In light of these startling statistics, actor, writer, activist, and Meteor founding member Amber Tamblyn wanted to hear from Lee—and understand how non-Asians can be allies. They sat down to talk about anti-Asian violence, movement-building, and what it means to create a culture of “grace.”

Amber: I’ve seen [the work] you’re doing to expose racism and violence—which is permeating both our culture and literally our streets, against Asian American elders. And I wonder if you would just talk a little bit about that and your experience fighting to bring more awareness to the violence that is happening in your community right now?

Min Jin: I think that is one of the reasons why I am speaking so consistently about the insult and the assault and the murders of Asians and Asian Americans in this country right now. There’s been an upsurge of such violence in the past several years, especially in light of the Trump administration. However, this kind of discrimination and exclusion has been happening, even by the state, ever since Asians and Asian Americans have been in this country.

Amber: I’ve read that the Asian American community in the US is one of the lowest communities to report violence and to report these assaults. And I was shocked by that statistic, but I [realize] it’s not so simple, [because] of the complicated relationship our country has with its police force.

Min Jin: There are so many, many poor immigrants in this country who are terrified of speaking up for fear of affecting their immigration status, for fear of affecting their jobs. And [many] even think that they don’t have the right to complain. They come from countries in which political persecution is so commonplace. [So] very often the victims won’t come forward for fear of persecution—and the persecution may not exist, but in their minds, it’s quite present.

So one of the things that I’m just trying to do is to bring greater awareness, to talk about it when I can. I’m asking the media to please pay attention to this situation. Part of it is representation, and part of it is telling the truth about how the economic disparity in our community is so, so wide. We have the poorest people in America, and we have some of the wealthiest people in America. So the idea [that] all Asian Americans are wealthy and educated is so completely, statistically, factually untrue. And if I could bring that to bear, then maybe I’ve done a little bit of truth-telling.

Amber: Watching the work that you have created in the last couple of years—both as a writer and a researcher, at the nexus of thrilling storytelling and unearthing these really hard truths—has been pretty profound. This is where, in my mind, for women, it’s not really a luxury to write about these things: This is not a hobby; this is an act of survival. How do you feel about that statement?

Min Jin: I think the word “survival” is so important because right now we are seeing girls and women under threat—especially poor girls and poor women, and that cuts across race, and it cuts across boundaries, and regions. We’re seeing political actors trying so hard to destroy the lives of girls and women. And I guess that’s the reason why I feel rather impassioned to make sure that our alliances get stronger, not [made] weaker by minor differences that we can definitely talk out.

Amber: I love that so much. And I needed to hear that because it has been a hard couple of years, as it has been for everybody. Obviously, I’ve dealt with my own feelings about the movement-building process and activist spaces that feel like we’re just ripping each other apart without the context of nuance and how difficult this work is. There is a world out there that just wants us not to exist and not to thrive. And also on a deeper, sadder level, not to love each other.

What you just said reminded me of this episode [of the On Being podcast] I just listened to [featuring] my friends Tarana Burke and Ai-Jen Poo. And there’s a thing that Tarana said: “I don’t think we can have movements that have liberation politics that don’t have a politic of grace.”

Min Jin: Amen. It should be exactly as Tarana Burke said, a “liberation ethic,” because it’s not just me getting whatever men get. It’s actually for all of us to be free to be who we’re supposed to be. And that’s a very revolutionary point of view.

Amber Tamblyn: What I’ve learned is, in any [movement] work, there’s a very delicate balance between honoring the wisdom and experience of your elders, and also breaking free of that to find what is important and needed in the current culture and climate.

Min Jin: Well, it’s funny, I’m 53 years old. I’m the middle girl of three girls in my family. My mother always worked and she earned money for our family, which was important. But then also I felt that our father really supported our full capacity as young women. So very often people talk about the patriarchy of East Asian Confucian cultures, and obviously, true. But my father— because he has three girls—I think he ended up feeling like, yes, I want you to be able to cook well. Which is obviously sexist. And yet, he also felt like you should be able to do whatever you want to do because my girls are the best.

He used to say, “Oh if a boy doesn’t want to marry you or date you because you’re smart and you’re educated, know this: He will have dumb children.”

Amber: Oh shit. That’s amazing.

Min Jin: Right? But my dad said that! I grew up in a very feminist household. So I’m always surprised when people say things about Asians and Asian Americans being sexist, because I’m like, “Well, that wasn’t my experience.”

Amber: That brings me to my [last] question that I wanted to ask you personally, but also for anyone reading this interview who’s also upset and outraged by [the rise of anti-Asian violence]. What is a very simple way to be more involved, to be more engaged?

Min Jin: The Alliance is an organization that supports victims [of anti-Asian violence] who wish to come forward. If they don’t have money for a lawyer, they have all these pro bono lawyers who are willing to do it. But very often the victims will not come forward. I think that you understand this very well as somebody who cares about the Me Too movement, [but] very often Asians and Asian-Americans are not believed. So, first of all, can you believe it when someone tells you, I’m afraid to take the subway, I’m afraid to walk down the street because somebody might attack me in a poor neighborhood? Secondly, find the [political] candidates who care about the core of your community.

The third thing is really simple: Sometimes, if you feel like it, you could offer to walk your friend somewhere. Sometimes it is a matter of reaching out, talking to the person who feels deeply ignored, [and] making him, or her, or them visible in your life. There are moments in recognition that we can give to each other, which can build a world and counteract all that cruelty.

Amber: I love that. What gives you hope about the future?

Min Jin: Well, I’m a mother and I’m a professor of young people, so the next generation obviously gives me hope. And what also gives me hope is that I come from a long history of women who are fighting for good things. And it’s so important to understand that we’re not alone in this. For me, I keep thinking about how many beautiful friendships I have found in the movement, [and] how many people I really adore, whose laughter I speak to when I’m having a hard time. Having a shared, common purpose is a wonderful way to build friendships. So that gives me a lot of hope.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.