Three Questions About…This Year’s Winter Olympics

The trailblazers to watch, and the ICE of it all

By Shannon Melero

Jamie Mittleman has the kind of job that, if it were explained in a Netflix rom-com, would sound entirely made up: She talks to Olympic and Paralympic athletes all day. Fine, it’s more than that; she’s the CEO and founder of Flame Bearers, a media company centered around women Olympians and their stories. But the fun part of her job is working with athletes and traveling to the Games.

The summer Olympics usually get all of the shine, but this year, the roster for Team USA is, as I think the kids say, bussin’. Two-time gold medalist Chloe Kim is back chasing a third podium. Figure skater Alysa Liu is out of retirement at the ripe old age of 22 and skating better than ever. Lindsey Vonn plans to compete on a totally destroyed ACL (girl, please don’t do that) and, of course, we’re all ready to get our Heated Rivalry on and cheer for the women’s ice hockey team captained by the incomparable Hilary Knight.

Ahead of her travels to the Milan/Cortina Olympics, Mittleman took some time to talk to us non-Olympians about what to expect.

The Olympics have always had political undertones. As someone working closely with so many women athletes ahead of Milan/Cortina, are there themes you’re seeing pop up?

A major theme I’m hearing from athletes is access. Who gets into winter sports? Who can afford it? Who sees themselves in it?

Winter sports remain some of the least diverse athletic spaces in the world, and athletes are acutely aware of that. They talk about the cost of equipment – how expensive is a ski pass? Hockey gear? A bobsled? [Plus] the lack of local facilities. Do they have to drive to get to the track? What if they don’t have a car? Nobody from my community competes in this sport…and how all of these compound over time.

There’s also a strong thread of athletes wanting to use their visibility to widen the doorway for the next generation. I’ve now worked with just shy of 400 Olympians and Paralympians from 55 countries, and many are navigating being “firsts” in their sport—first from their country, first openly queer, first Black athlete in their discipline. They’re proud, but they’re also very aware of the weight of representation they carry. It’s a privilege, but it’s also a responsibility they didn’t necessarily sign up for.

Speaking of firsts, Team USA has two major ones on the roster this year with Amber Glenn, the team’s first openly queer figure skater, and Laila Edwards, the first Black woman to play ice hockey for the U.S. What are you hoping viewers can take from watching them compete?

Seeing Amber Glenn and Laila Edwards on this stage matters far beyond medals. I hope young viewers see that there is no single mold for who belongs in sport. In her "Making It To Milan" interview, Hilary Knight mentioned, "There is a place for everyone in sport.” You can be openly queer and compete at the highest level. You can be a Black woman in a sport that has historically excluded you. You don’t have to shrink yourself to fit into a system.

For many young people watching, this may be the first time they see someone who looks like them, loves like them, or comes from a background like theirs on Olympic ice and snow. That moment of recognition matters. It’s often the first spark of belief: Maybe I belong there too. That belief is why my company exists—to make it clear that you do.

It’s also important to mention that just as many “firsts” exist in the Paralympics, which begin immediately after the Olympics—and I highly recommend tuning in.

We recently learned that ICE is also going to Milan with Team USA—which as an Olympic fan, fills me with embarrassment during a time I’d normally be feeling a rare moment of national pride. Does that change the viewing experience for you at all?

ICE traveling with the U.S. delegation is fundamentally at odds with the spirit of the Olympic Games, a hollow stunt of performative power. While hidden under the guise of ‘protection’, this move reads less as a safety measure and more as a PR maneuver—an attempt by the Trump administration to reclaim international relevance and authority at a moment when the US is increasingly isolated and losing credibility. Coming on the heels of Davos, where international leaders such as Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney signaled clear resistance to Trump’s agenda, ICE’s presence is an attempt to project strength at a time when US influence has clearly decayed.

Outside the US, the context is very clear: ICE is not relevant, nor wanted. The International Olympic Committee has said their presence is ‘distracting and sad.’ The Mayor of Milan explicitly said they are not welcome. Since the announcement of their presence, several organizations have moved to disassociate from the word “ICE.” The Milan hospitality suite, once called the “Ice House” has already been renamed.

[But their presence] reinforces why the athletes’ stories—and their humanity—matter even more. The athletes are showing up to compete after lifetimes of work. This is about them. Their journeys. Many come from immigrant families, from underrepresented communities, from places where sport was their pathway to opportunity. The geopolitical backdrop is real, but what I see up close is athletes trying to hold onto the purity of why they do this in the first place.

Three Questions About...Getting Fired

No shame in getting shitcanned, say Laura Brown and Kristina O’Neill

By Cindi Leive

Getting unceremoniously sacked has always been an occupational hazard for magazine editors; back in the 1980s, Vogue’s Grace Mirabella reportedly found out she’d been let go when she heard it on the TV show Live at Five. But when it happened to Laura Brown (the former head of InStyle) and Kristina O’Neill (of WSJ Magazine), they eventually realized that, to quote Nora Ephron, everything is copy. These two friends (and, full disclosure, friends of mine) sat down to write a book about the experience: All the Cool Girls Get Fired, in which everyone from Oprah to Jane Fonda tell their own pink-slip stories.

It couldn’t be better timed. Earlier this fall I ran into an acquaintance on the subway and was telling her about the book. We noticed a woman next to us leaning close. “I”m sorry,” she said, “would you mind saying the name of that book again? I need it.”

In case you do too, here are three questions for the authors.

My first question is, the book is All the Cool Girls—not all the cool boys—Get Fired. So I'm curious—how is the experience of getting fired for women different than it is for men? Obviously, it happens to them too.

Kristina O’Neill: We noticed that there was a universality around the shame and the embarrassment and the disappointment that women respond to this sort of life event with. We noticed that a lot of men, if it has happened to them, it almost becomes part of their armor and part of their narrative—I mean, Steve Jobs, Mike Bloomberg, they made getting fired part of their entire work journey. Whereas when we sat down to write this book, we couldn't easily identify women who, after having been fired, owned it. It does seem like women have a harder time just saying what happened to them and moving on psychologically.

Laura Brown: I asked [human resources pro] Bucky Keady: Why does it hit so much harder [for women]? And in one second she said, “Because it took so much longer to get there. It took us so much longer to get into that room.” So many of us feel shame and wallow. But it’s futile. And you have a community, but you're not going to find the community unless you put your hand up: Actually, me too. That happened to me as well. And then, God, that's a help. That's such a relief. But you have to speak up.

Whose story of being fired surprised you, or made you see their career differently?

KO: We were really struck by how many women hadn't talked about it before. Katie Couric, for example, kept saying, Well, they didn't renew my contract, and it was almost like a revelation in the conversation when I think it sort of dawned on her, like, Yeah, I guess I was getting fired! We [also] talked to a sports agent, Lindsay Colas, who’s brilliant and who literally got Brittney Griner out of prison in Russia, and another client called her after she got Brittney out of jail and said [something to the effect of], “You haven't been paying enough attention to us, we're going to go with a different agency!”

So fired looks different for everybody: the language around it, the experience, the aftermath. But the universal thing is you feel like shit.

LB: One of my favorite stories was from Tarana Burke; she was running an organization in Philly and she was comfortable there. Then she got fired. And in all this time, me too was sort of lying dormant in her head. So when she was fired, she was then allowed to open her mind to proceed with that. She said, I kept thinking, You've been carrying other people's visions to fruition for too long. And she was able to carry her own.

How much did you know about Oprah’s firing [from her job as co-anchor of the Baltimore evening news] before interviewing her?

LB: We knew the story a little, but again—it wasn’t the [big narrative] about her. She should be on the fired Mt. Rushmore with Steve Jobs and Mike Bloomberg and everyone else! When we talked to her, her memory of the firing was like muscle memory. It was so visceral. [“I really have never talked about it,” says Oprah in the book.] She remembered what the managing director of the TV network was drinking. She remembered it was April Fools’ day, and she thought it was an April Fools’ joke. Bang, bang, bang, bang, bang, she remembered all these things because sadly—it's almost like with Instagram comments when you remember the negative one and you forget all the nice ones. And Oprah got upset about it anew, but she was us. She was ashamed to tell her dad, she was ashamed she lost her job. But her story reminds you that [getting fired] fires up your dreams too.

KO: If it hadn't happened to her, she would've never been in the prime position to be put up for that talk show.

LB: Oprah told us, The setback is a setup. It's so tidy, but it's absolutely true: That thing that knocks you down can spring you back.

Three Questions About...Like, Words and Stuff

Journalist Megan Reynolds takes up the most derided word in the dictionary

By Shannon Melero

Megan Reynolds has always had a way with words, which I experienced firsthand when we worked together at Jezebel, and she told me I could always go to her with any questions. Big mistake, huge! I’ve been pestering her since 2019, and now I have yet another reason: Megan—who has made everything from beach chairs to a really big mall to the terrible sport of baseball come alive with her deft use of language,—has a new book, Like: A History of, Like, the World’s Most Hated (and, Like, Misunderstood) Word. In it, she traces the word’s origins all the way back to the 1600s, and also writes a love letter to the way women, particularly teen girls, have shaped language. As is our routine, I darkened her door with my queries.

So even though women are the ones making fetch happen when it comes to language, this book exists because there’s so much pushback and policing over women’s use of “like.” So I guess my question is, why can’t we just, like, talk how we please?

The answer is absolutely “sexism,” but that is a pat response for a situation that is much more nuanced and complex. Sometimes the call is coming from inside the house—for all the professional men out there who write earnest LinkedIn blogs about filler words, power, and corporate communication, there are just as many professional women doing the same thing. The policing comes in many forms, [including] the voice in your own head, but I’d say that it is most evident in the aforementioned blogs on LinkedIn and op-eds in various newspapers around the world. And, if you watch the season premiere of the most recent season of The Kardashians on Hulu, you’ll find the entire family policing Kourtney for saying like, like, all the time.

On the surface, any policing of women’s language looks like and definitely is sexist, but underneath, is also the issue of intelligence and whether or not saying “like” a bunch when you talk means you’re not. And yes, this is a battle that both men and women face, but women (I assume) are more concerned with not sounding stupid, whereas men will happily open their mouths and share the first thought that comes to mind.

One thing I love is that you described "like" as a word that does a lot of emotional labor, and it's been doing so since before either of us was born. Have you come across a word that is taking on that same labor for the next generation? Or will "like" continue to be a timeless linguistic accessory?

Language moves faster than any of us are interested in thinking about, but I think that “like” will never go out of style—and that’s actually good? It means that it’s become an inherent and natural part of speech, and for that, we are forced to stan. However, the youth of today are saying words in ways that I never could have imagined.

The meaning of “literally” has changed in recent years due to young people using it in unorthodox ways, and I think a lot of people are pressed about that for reasons unbeknownst. Technically, “literally” does mean just one thing, and often, it’s used in situations that are decidedly not literal. And like “like” can function as an intensifier, “literally” does the same thing.

You write about how Serious Feminists™ of the past were also a part of the anti-Like movement. Is there still a sense that we need to sound important if we want to be important?

Like with most things in life, the answer depends on the person. I’ve worked with women who are younger than me but much more “professional,” hewing closer to the traditional and generally accepted definition of what that sounds like. To me, this doesn’t matter at all. And because I’m generally not that “professional” by any commonly-held, old-fashioned standard, my aim in writing this book was to communicate that we don’t need to care about this! It doesn’t matter! If someone is or isn’t going to take you seriously in the workplace or anywhere else, I’d wager that they’ve already made that decision before you even opened your mouth, anyway.

Three Questions About...Toni Morrison

She had a whole other job, and she was brilliant at it.

By Rebecca Carroll

Toni Morrison wrote some of the greatest literature of all time. It is less known, though, that she also edited some of the greatest literature, and that is what makes Dana A. Williams’s new book, Toni At Random: The Iconic Writer’s Legendary Editorship, such a gift. Williams, a professor of African American literature and the Dean of Graduate School at Howard University, conducted hundreds of interviews (including a handful with Morrison while she was still living) and unearthed letters and conversations between Morrison and the authors she published—among them Toni Cade Bambara, Lucille Clifton, Gayl Jones, and Angela Davis—during her nearly 20 years as an editor at Random House. The result is a thoughtfully reverent, always engrossing, and occasionally juicy narrative that confirms Morrison’s intricate genius, as well as her deep love of Black writers, Black books, and Black language.

Rebecca Carroll: What did you learn about Toni Morrison, the editor, that you did not know about Toni Morrison, the writer?

Dana A. Williams: I think they intersect, but Toni Morrison as editor was fully involved in the publishing community. I think of Toni Morrison-as-writer as someone writing in isolation—someone writing at their desk, really thinking about her story and her characters. Morrison as editor was everywhere. She was at every party. She was in the design team’s face, sometimes to their dismay. She was on the street trying to find writers, because she really did have to kind of beat the bushes in those early years to identify writers who had not been signed up by other houses. Angela Davis told me that her office was always bustling. There were people in and out all the time, which is part of the reason why, when she was working on a book of her own, she would not go in the office in the same way.

One of the beautiful things about this book has been rediscovering books I’ve loved forever, like Toni Cade Bambara’s Gorilla, My Love, now knowing that Morrison played such an integral role in shaping them. Were there books that you returned to in the same way during the process of writing this one?

I absolutely went back and reread [Bambara’s] The Salt Eaters because I thought, Now I think I know what’s happening in this book. I love The Salt Eaters. I taught The Salt Eaters, but I never got all of it. The same thing was true of Leon Forrest, who I probably knew more about than any of the authors. All the fiction—the fiction [Morrison edited] was what I was so drawn to to begin with….But the more [Morrison and I] talked, the more she continued to ignore my questions about fiction. She was like the queen of indirection from the beginning to the end, because she never said, “This book really shouldn’t be about the fiction only.” She would drop hints like, “Have you seen Paula’s last book? Now that’s a book. If you’re going to write a book, that’s a book.” She was talking about A Sword Among Lions by Paula Giddings, which was interesting, because it is a biography of Ida B. Wells, and every time I would ask [Morrison] a question about herself, she would say, “I'm not interested in myself.”

After spending over a decade on this book, do you have a strong sense now of what Toni Morrison thought made good writing?

I kept asking her that question, and she said, “Well, obviously if it’s nonfiction, the argument has to be sound and it has to be compelling, and it has to make the case for the reader in a way that nobody else has made it before.” If she was editing on a topic that she didn’t know as much about, she was literally reading everything about the current conversation to make sure [the author was] moving this argument in a different direction. Editors don't have to do that.

For the fiction…I think she was more drawn to experimental writers than to straight beginning, middle, and end writers. She said, “With Gayl Jones, I had to ask questions about characters: What is motivating this character?” With Bambara, she said, “I just needed to make sure that she didn't leave the reader behind, because she’s moving so fast.” I kept thinking, There has to be this kind of crystallized way of saying [what good writing is]. But it was the interrogation. I think that was her distinguishing mark—to publish what stories she wanted to be told, and to let the writer be the writer.

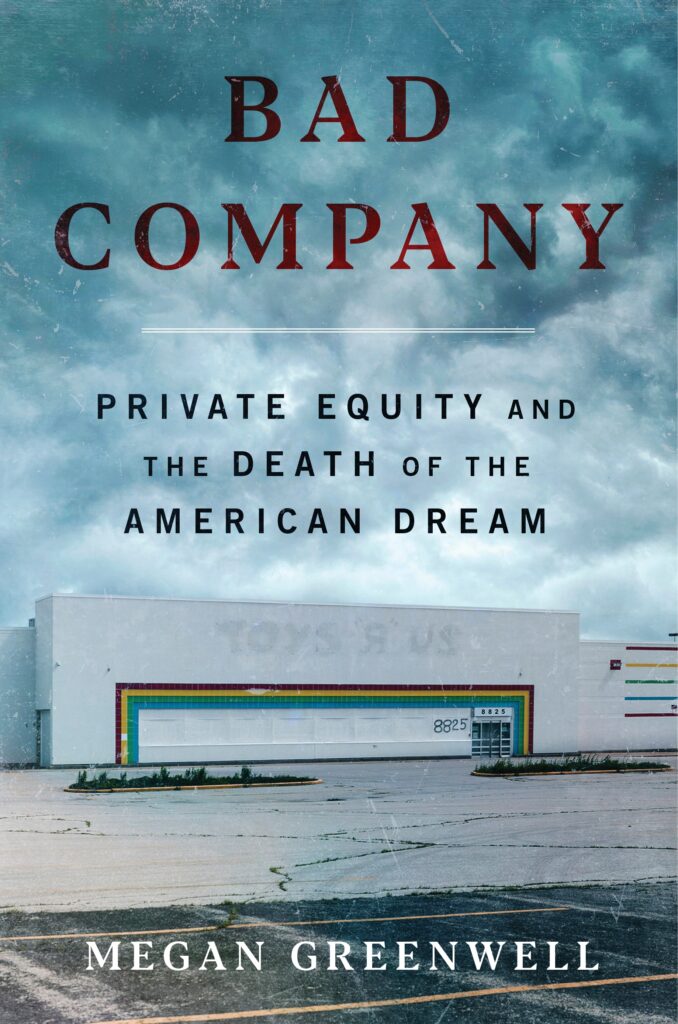

Three Questions About...Private Equity

In her new book, author Megan Greenwell humanizes the horrors of a secretive industry

By Nona Willis Aronowitz

When journalist Megan Greenwell scored her dream job as the editor-in-chief of the sports website Deadspin, she hadn’t thought about private equity at all. She had never done any finance reporting, and she had only the vaguest sense of what private equity even did. But when, in 2019, Deadspin was being destroyed by the firm that owned it, she wrote a scorched-earth resignation letter and resolved to learn more about the human cost of this ubiquitous and insidious industry. Her resulting book, Bad Company: Private Equity and the Death of the American Dream, tells the story of four people whose lives were upended by private equity–and how they all fought back.

John Oliver once said, “If you want to do something evil, put it inside something boring.” Your book is not boring, but I think for many of us, our eyes glaze over at financial terms we don’t know. How do you explain private equity to get laypeople to care?

The only way I wanted to write this book was if it was for people who have some sense that private equity is important and has negative consequences, but have zero idea what that means. Here’s how I describe it: The engine of the private equity machine is leveraged buyouts, which are when a private equity firm pools money from outside investors–pension funds, university endowments, ultra-wealthy individuals, what have you–and combines that money with a huge amount of bank loans, then uses that combined fund to buy companies.

The trick is that the debt from the loans is assigned not to the private equity firm but to the company it is acquiring. That’s the detail I think gets people scandalized. They take companies that are pretty strong in a lot of cases and turn them into companies absolutely hamstrung by debt payments, and as a result, 10 times as many companies owned by private equity declare bankruptcy than other kinds of companies. The private equity firms themselves don’t take on any risk, but this has horrible effects on communities, workers, tenants, patients, everybody.

The book’s subtitle mentions “the death of the American dream.” How did this theme play out in your reporting? (Also, I have to ask: Was it just a coincidence that three out of four of your protagonists were women, or do you think there’s a throughline there?)

I picked the industries first, and I landed on media, healthcare, retail, and housing. Private equity didn’t cause the root problems in these industries; instead, they capitalized on those problems for their own gain. Once I had my protagonists, the interviews drove the American Dream theme rather than the other way around. One is a Mexican immigrant who moved here in middle school, not speaking a word of English, and who managed to become a professional journalist. Another grew up poor in Texas, and his version of the American dream was becoming a community doctor who provided care to his neighbors. Another was a woman who escaped public housing (and a lot of other things), so for her, living in her apartment complex really was the Dream. And the last woman is an Alaska native who moved to the mainland and supported a family of five on a Toys “R” Us retail salary so her husband could go to pharmacy school and make a better life for all of them. In each case, private equity ended up tearing down the things that were most important to these people.

[And about the three-out-of-four women factor,] it’s not surprising to me that women were the majority of people I ended up talking to–not just [of] the four, but the 150 to 200 people I spoke with before I found my protagonists. In part, it’s because there are specific vulnerabilities of being a woman in 21st century America [like poverty] but also because I chose people who were fighting back, and women seem to be more involved in these community fights.

Yes–all of your subjects actively resist their circumstances to varying degrees after private equity shatters their lives. What can someone whose job or industry is being eviscerated by private equity learn from the people in your book?

The four characters in my book all fight back in very different ways. Some put pressure on elected representatives [to regulate private equity]–although there are limitations to that at the federal level, because fully 88% of members of Congress and the Senate take private equity donations. Another character does some lobbying in front of pension funds to get them to stop investing in private equity firms that hurt workers. There’s some true grassroots community organizing to build something new. Some of the most interesting reporting I did was in the media section, where the focus is on people who are trying to create a new nonprofit system. Is that at a big enough scale now that it is fully replacing private equity-owned corporate media? No. But some startup nonprofit local news sites are doing really, really well economically and are becoming amazing sources of news in places that didn’t have news. I think about Mississippi Today, which did not exist until a few years ago, but which won a Pulitzer by exposing a massive scandal in the governor’s office involving Brett Favre. That’s genuinely inspiring to me.

Three Questions About...Wellness

Amy Larocca, author of a big new book on the industry, separates the harmless from the hoaxes

By Cindi Leive

One of the many developments of the last decade—along with the rise of AI, Trumpism and tradwives—is the vast and varied world known as “wellness,” which includes everything from that meditation app on your phone to billion-dollar biohacking. Journalist Amy Larocca has spent seven years making sense of it all, and her book, How to Be Well: Navigating our Self-Care Epidemic, One Dubious Cure at a Time, is out today. Despite its skeptical subtitle, Larocca understands that “wellness culture is too big for us to be either completely for or against it.” So where did she land? I wanted to know.

Your book investigates the recent rise of wellness culture. But back in the ‘80s, there were grapefruit diets and aerobics classes and all kinds of physical expectations. What’s different now?

A lot of it in the 80s was about looking good, or slimness—I can still picture the Dexatrim box! But there wasn't a lot of thought about health in mainstream culture. I really started to notice the rise in wellness culture when I was working as a fashion editor [at New York magazine in the 00s-10s]. Fashion was becoming more democratic—you could stream the shows, you could shop online. But at the same time, health was becoming more and more expensive and out of reach. Basic healthcare was not being treated as a right in the United States, but as a luxury commodity. And I could see that it was being marketed using all of the same language as the fashion industry that I'd been covering. And how weird is it that the new luxury good is our health, something that isn't extra, right? A handbag or a pair of shoes or a lipstick is something that's extra, but our health shouldn't be extra.

You started writing this book seven years ago—when, yes, there were colonics and juice cleanses, but you could still go to the CDC for solid information about what worked or didn’t. Now our top public health leaders are trafficking in disproven myths about vaccines and cancer and birth control and fluoride. Did you see this coming?

I feared that it would get as bad as it has gotten. And one of the reasons that wellness culture has been able to rise in the way that it has, especially for women, is there's a real absence of experts. The writer Maya Dusenbery [has] said that it drives her crazy when women seeking wellness care are described as seeking “alternative solutions.” Because these aren't alternatives: We don't really have other choices! Women are going online looking for advice from other women for managing their autoimmune conditions because autoimmune disease and other diseases that have disproportionately affected women have been very underfunded and understudied. So when women are using this relatively new resource called the internet to speak to each other and discuss what has worked for them and how they've managed—that's not alternative. That's just us actually trying to find some relief because the mainstream channels have let us down. [And] given the current political situation, I don't see that getting any better.

Your book makes it really clear that progress and bullshit are really intertwined. Meditation is incredibly helpful to a lot of people and it’s being oversold as a solution. Our health-care system does need to focus more on menopause and there’s now a lot of menopause-related crap being sold to us with cutesy names. So is there a wellness development that you find really promising, and one that feels particularly BS-laden at the moment?

For years, there was a conversation about [hormone replacement therapy] HRT being very, very, very dangerous for women, so women stopped taking HRT. Then NAMS re-released its research and talked about HRT being safe for women—that coincided with the rise of telehealth [in COVID] and suddenly you had a number of telehealth startups making HRT very, very, very easily accessible. So you combine all that in a perfect storm and you get a lot of women with very high expectations for what HRT is going to be able to do for them during perimenopause—and all this is doing exactly what wellness culture has the potential to do in the worst possible way: It oversimplifies matters with a profit motive behind it all.

The real story of HRT is: Here's a treatment that can help some women with some symptoms some of the time, but the only narratives that seem to gain any traction are “It will kill you!” or “It will save you, hurl down your crutches, Oh Lord, I can walk!” And neither of those stories seem to me to be the correct story of HRT, but no one seems to have any tolerance for anything in the middle.

Part of that seems to be driven by how much money there is to be made. Part of it seems to be driven by the appetite for a good story. Part of it seems to be driven by a lack of patience for complexity, and how boring medicine can actually be. But it really started to freak me out—the expectations that people seemed to start having for what HRT was going to do for them, and the amount of money that a number of business people were excited to suddenly make. And that's wellness culture in a nutshell.

I’m breaking the rules of this column with a fourth question. Is there one particular wellness habit you've picked up while writing the book that you will keep?

Breathing. It’s free. I do 4-7-8 breathing. I'm big on all the free stuff: I walk everywhere, and I sleep. Sleep as much as you possibly can, and never, ever, ever feel guilty for going to bed.