Three Questions About…This Year’s Winter Olympics

The trailblazers to watch, and the ICE of it all

By Shannon Melero

Jamie Mittleman has the kind of job that, if it were explained in a Netflix rom-com, would sound entirely made up: She talks to Olympic and Paralympic athletes all day. Fine, it’s more than that; she’s the CEO and founder of Flame Bearers, a media company centered around women Olympians and their stories. But the fun part of her job is working with athletes and traveling to the Games.

The summer Olympics usually get all of the shine, but this year, the roster for Team USA is, as I think the kids say, bussin’. Two-time gold medalist Chloe Kim is back chasing a third podium. Figure skater Alysa Liu is out of retirement at the ripe old age of 22 and skating better than ever. Lindsey Vonn plans to compete on a totally destroyed ACL (girl, please don’t do that) and, of course, we’re all ready to get our Heated Rivalry on and cheer for the women’s ice hockey team captained by the incomparable Hilary Knight.

Ahead of her travels to the Milan/Cortina Olympics, Mittleman took some time to talk to us non-Olympians about what to expect.

The Olympics have always had political undertones. As someone working closely with so many women athletes ahead of Milan/Cortina, are there themes you’re seeing pop up?

A major theme I’m hearing from athletes is access. Who gets into winter sports? Who can afford it? Who sees themselves in it?

Winter sports remain some of the least diverse athletic spaces in the world, and athletes are acutely aware of that. They talk about the cost of equipment – how expensive is a ski pass? Hockey gear? A bobsled? [Plus] the lack of local facilities. Do they have to drive to get to the track? What if they don’t have a car? Nobody from my community competes in this sport…and how all of these compound over time.

There’s also a strong thread of athletes wanting to use their visibility to widen the doorway for the next generation. I’ve now worked with just shy of 400 Olympians and Paralympians from 55 countries, and many are navigating being “firsts” in their sport—first from their country, first openly queer, first Black athlete in their discipline. They’re proud, but they’re also very aware of the weight of representation they carry. It’s a privilege, but it’s also a responsibility they didn’t necessarily sign up for.

Speaking of firsts, Team USA has two major ones on the roster this year with Amber Glenn, the team’s first openly queer figure skater, and Laila Edwards, the first Black woman to play ice hockey for the U.S. What are you hoping viewers can take from watching them compete?

Seeing Amber Glenn and Laila Edwards on this stage matters far beyond medals. I hope young viewers see that there is no single mold for who belongs in sport. In her "Making It To Milan" interview, Hilary Knight mentioned, "There is a place for everyone in sport.” You can be openly queer and compete at the highest level. You can be a Black woman in a sport that has historically excluded you. You don’t have to shrink yourself to fit into a system.

For many young people watching, this may be the first time they see someone who looks like them, loves like them, or comes from a background like theirs on Olympic ice and snow. That moment of recognition matters. It’s often the first spark of belief: Maybe I belong there too. That belief is why my company exists—to make it clear that you do.

It’s also important to mention that just as many “firsts” exist in the Paralympics, which begin immediately after the Olympics—and I highly recommend tuning in.

We recently learned that ICE is also going to Milan with Team USA—which as an Olympic fan, fills me with embarrassment during a time I’d normally be feeling a rare moment of national pride. Does that change the viewing experience for you at all?

ICE traveling with the U.S. delegation is fundamentally at odds with the spirit of the Olympic Games, a hollow stunt of performative power. While hidden under the guise of ‘protection’, this move reads less as a safety measure and more as a PR maneuver—an attempt by the Trump administration to reclaim international relevance and authority at a moment when the US is increasingly isolated and losing credibility. Coming on the heels of Davos, where international leaders such as Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney signaled clear resistance to Trump’s agenda, ICE’s presence is an attempt to project strength at a time when US influence has clearly decayed.

Outside the US, the context is very clear: ICE is not relevant, nor wanted. The International Olympic Committee has said their presence is ‘distracting and sad.’ The Mayor of Milan explicitly said they are not welcome. Since the announcement of their presence, several organizations have moved to disassociate from the word “ICE.” The Milan hospitality suite, once called the “Ice House” has already been renamed.

[But their presence] reinforces why the athletes’ stories—and their humanity—matter even more. The athletes are showing up to compete after lifetimes of work. This is about them. Their journeys. Many come from immigrant families, from underrepresented communities, from places where sport was their pathway to opportunity. The geopolitical backdrop is real, but what I see up close is athletes trying to hold onto the purity of why they do this in the first place.

A Bigger, Badder, Bunnier Bowl

February 5, 2026 Hey there Meteor readers, Nona and I both woke up this morning with fevers and intense cases of the daycare schmutz. So this newsletter is brought to you by Tylenol, Ricola, and some nasty-ass ginger tea.  Today, we’re going full Sporty Spice with some emotional prep for Bad Bunny’s halftime performance this weekend. Plus three questions about what athletes are facing at the Winter Olympics. Achoo 🤧, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONDomingo Gigante: Last weekend, during his Grammy acceptance speech for Album of the Year, Bad Bunny opened with a vastly underappreciated line: “Puerto Rico, créeme cuando te digo que somos mucho más grandes que 100 por 35.” If you haven’t gotten your Duolingo minutes in today, that’s “Believe me when I tell you, we’re so much bigger than 100x35,” which are the land measurements of Puerto Rico’s main island. The rest of his message, delivered mostly in Spanish, touched on perseverance. But the idea of being bigger is what’s stayed with me these last few days, particularly in a political moment where the best thing anyone can be is unseen. Unseen by ICE agents lingering in train stations. Unseen by trigger-happy police officers. Unseen by right-wing extremists. Stepping out of my house every day, my greatest desire is for my family to go completely unnoticed and make it back safely. But throughout his career, Bad Bunny has defied the idea of being small, of asking permission to enter a space as his authentic self. He just shows up. He simply is, and he does it loudly, boldly, and sometimes in a fabulous gown. He’s done so in a way that his musical forefathers—DY, Marc Anthony, Tego Calderon—never could because they were either trapped in the Latin music gilded cage, or chose to avoid politics until much later in life. For all their fame, they were also kept smaller by (mostly) American audiences and an industry that sees Latin music and people as separate from the American identity. But in the words of another great, Residente, “América no es solo USA, papá.”  HOW WE'RE ALL ABOUT TO BE SMILING THIS SUNDAY. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Of course, the ability to make yourself more or less visible is rooted in privilege. White and light-skinned artists can take a step back *cough* JLo *cough* in a way that protects them from the ire of entire administrations. After all, Turning Point wasn’t running counter programming in 2020 when JLo and Shakira headlined the halftime show. Conservatives did, however, have a ton to say after Kendrick Lamar’s performance last year. (I guess a Black, California-born Pulitzer Prize winner just isn’t American enough?) And despite making no noise over Green Day, who are performing on Sunday as well and have an entire album devoted to political criticism, conservatives have been spending the last few months proselytizing about how un-American it is to have a Spanish-language artist take center stage at the Super Bowl. (Let’s all be honest with ourselves for a minute, y'all don’t want most of these songs translated. I promise you chocha is not going to hit the same in English.) Which is why Bad Bunny’s choice to use his privilege to step into the fray rather than avoid it is so important. His pride is not a performance piece he takes on and off when the mood suits—and that kind of authenticity encourages others to walk in pride. It’s bigger than a 15-minute set we won’t remember a year from now. It’s bigger than 100x35. It’s a call to know who you are—your history, your symbols, your land, your people—and to stand tall, whether or not you are acceptable to the powers that be. Especially when you’re not. AND (promise a sports break):

PENNY THE DOBERMAN PINSCHER, THIS YEAR'S BEST IN SHOW. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)  Three Questions About...This Year's Winter OlympicsThe trailblazers to watch and the ICE of it all.BY SHANNON MELERO  LAILA EDWARDS (FRONT, BLUE) AND TEAM USA HOCKEY FACED OFF AGAINST CZECHIA THIS WEEK, AND SECURED THEIR FIRST WIN OF THE GAMES. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Jamie Mittleman has the kind of job that, if it were explained in a Netflix rom-com, would sound entirely made up: She talks to Olympic and Paralympic athletes all day. Fine, it’s more than that; she’s the CEO and founder of Flame Bearers, a media company centered around women Olympians and their stories. But the fun part of her job is working with athletes and traveling to the Games. The summer Olympics usually get all of the shine, but this year, the roster for Team USA is, as I think the kids say, bussin’. Two-time gold medalist Chloe Kim is back chasing a third podium. Figure skater Alysa Liu is out of retirement at the ripe old age of 22 and skating better than ever. Lindsey Vonn plans to compete on a totally destroyed ACL (girl, please don’t do that) and, of course, we’re all ready to get our Heated Rivalry on and cheer for the women’s ice hockey team captained by the incomparable Hilary Knight. Ahead of her travels to the Milan/Cortina Olympics, Mittleman took some time to talk to us non-Olympians about what to expect. The Olympics have always had political undertones. As someone working closely with so many women athletes ahead of Milan/Cortina, are there themes you’re seeing pop up? A major theme I’m hearing from athletes is access. Who gets into winter sports? Who can afford it? Who sees themselves in it? Winter sports remain some of the least diverse athletic spaces in the world, and athletes are acutely aware of that. They talk about the cost of equipment – how expensive is a ski pass? Hockey gear? A bobsled? [Plus] the lack of local facilities. Do they have to drive to get to the track? What if they don’t have a car? Nobody from my community competes in this sport…and how all of these compound over time. There’s also a strong thread of athletes wanting to use their visibility to widen the doorway for the next generation. I’ve now worked with just shy of 400 Olympians and Paralympians from 55 countries, and many are navigating being “firsts” in their sport—first from their country, first openly queer, first Black athlete in their discipline. They’re proud, but they’re also very aware of the weight of representation they carry. It’s a privilege, but it’s also a responsibility they didn’t necessarily sign up for. Speaking of firsts, Team USA has two major ones on the roster this year with Amber Glenn, the team’s first openly queer figure skater, and Laila Edwards, the first Black woman to play ice hockey for the U.S. What are you hoping viewers can take from watching them compete?  EDWARDS AT A WELCOME EVENT IN MILAN MAKING BLACK HISTORY DURING BLACK HISTORY MONTH. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Seeing Amber Glenn and Laila Edwards on this stage matters far beyond medals. I hope young viewers see that there is no single mold for who belongs in sport. In her "Making It To Milan" interview, Hilary Knight mentioned, "There is a place for everyone in sport.” You can be openly queer and compete at the highest level. You can be a Black woman in a sport that has historically excluded you. You don’t have to shrink yourself to fit into a system. For many young people watching, this may be the first time they see someone who looks like them, loves like them, or comes from a background like theirs on Olympic ice and snow. That moment of recognition matters. It’s often the first spark of belief: Maybe I belong there too. That belief is why my company exists—to make it clear that you do. It’s also important to mention that just as many “firsts” exist in the Paralympics, which begin immediately after the Olympics—and I highly recommend tuning in. We recently learned that ICE is also going to Milan with Team USA—which as an Olympic fan, fills me with embarrassment during a time I’d normally be feeling a rare moment of national pride. Does that change the viewing experience for you at all? ICE traveling with the U.S. delegation is fundamentally at odds with the spirit of the Olympic Games, a hollow stunt of performative power. While hidden under the guise of ‘protection’, this move reads less as a safety measure and more as a PR maneuver—an attempt by the Trump administration to reclaim international relevance and authority at a moment when the US is increasingly isolated and losing credibility. Coming on the heels of Davos, where international leaders such as Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney signaled clear resistance to Trump’s agenda, ICE’s presence is an attempt to project strength at a time when US influence has clearly decayed. Outside the US, the context is very clear: ICE is not relevant, nor wanted. The International Olympic Committee has said their presence is ‘distracting and sad.’ The Mayor of Milan explicitly said they are not welcome. Since the announcement of their presence, several organizations have moved to disassociate from the word “ICE.” The Milan hospitality suite, once called the “Ice House” has already been renamed. [But their presence] reinforces why the athletes’ stories—and their humanity—matter even more. The athletes are showing up to compete after lifetimes of work. This is about them. Their journeys. Many come from immigrant families, from underrepresented communities, from places where sport was their pathway to opportunity. The geopolitical backdrop is real, but what I see up close is athletes trying to hold onto the purity of why they do this in the first place. You can listen to Flame Bearers' full Making it to Milan series here.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Hell Hath No Fury Like a Woman Voting

November 6, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, Welcome to the Mamdaniverse, where hope is alive and all foods have seasoning you can actually taste.  Today’s newsletter is just like my high school: all girls, with a couple of body slams to end the night. Should be fun! Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONSuper graphic ultra modern girls: The numbers are in, the Blue Wave has risen, and riding atop the crest on their vote-shaped surfboards are thousands upon thousands of women. According to exit poll data from the AP, in Tuesday’s three key races (New York, New Jersey, and Virginia), roughly 8 in 10 women supported Democrats, compared to 6 in 10 men. Young women in particular—and yes, we do mean Gen Z even though the rest of you are still young at heart—showed up and showed out for their candidates. What was it that rallied women under 30 to the polls this year? “They want a leader who is going to push back on the misogynist rhetoric coming from these conservative leaders,” explains Rachel Janfaza, the founder of The Up and Up, a research and strategy firm focused on Gen Z. “The way that women have been talked about, especially in some of these right-wing ecosystems, has really pissed women off.” Janfaza’s research also shows that younger women “are really taking their vote seriously…[and] their civic engagement seriously,” which doesn’t surprise her. Young millennials and Gen Zers are struggling under an economy that’s been unstable for years—economics and cost of living were the highest priority issues for a majority of voters this election cycle—and also grappling with the rollback of abortion rights. “This is an issue-driven block of women,” Janfaza says. “They’ve grown up with less rights, which is very motivating, and they’re looking to back candidates who will show up and fight for them.” AND:

(VIA GETTY IMAGES)

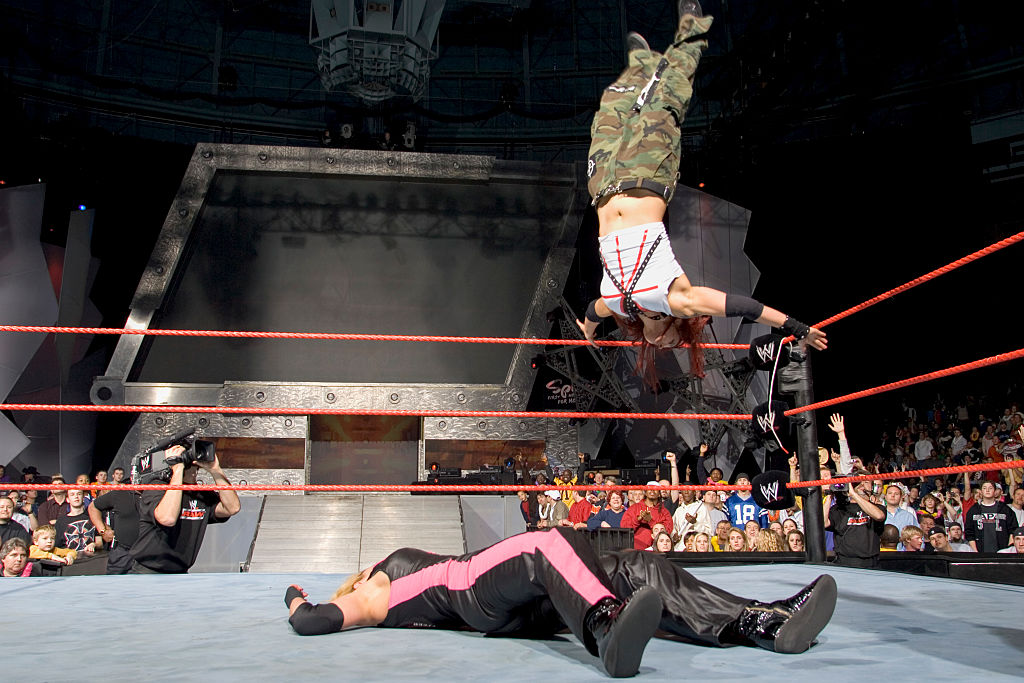

The Future of Women’s Wrestling Is Big and Bright in TexasWelcome to MetroplexBY SCARLETT HARRIS  WRESTLER AND METROPLEX OWNER, ATHENA (COURTESY OF METROPLEX WRESTLING) On the last Sunday in October, in a suburb nestled between Dallas and Fort Worth, Texas, a group of women came together for an all-women’s wrestling show hosted at Metroplex Wrestling, a woman-owned wrestling school. Titled Who Runs the World?, the show was the brainchild of All Elite Wrestling star Athena, and it followed a rousingly successful inaugural show in August; both shows featured some of the biggest names in independent women’s wrestling, including Mercedes Moné, Nyla Rose, and Kris Statlander. A third production is scheduled for January 2026, and will also stream on Twitch. This sequence of events on the indie scene—three all-women shows in six months!—is a welcome contrast to the mainstream entity World Wrestling Entertainment, which has staged just two all-women wrestling shows in its 70 year history. A TAG TEAM BATTLE BETWEEN GIGI REY & LADY BIRD MONICE MONROE AND ANARKID ASH & LONDYN DIOR (COURTESY OF METROPLEX WRESTLING) Progress for women in WWE has been slow and fitful. Earlier this year, WWE hosted Evolution 2, the much-anticipated sequel to its 2018 show of the same name. In an industry dominated by polarizing macho figureheads like the late Hulk Hogan, both Evolutions were hard-won victories in what we can call wrestling’s second-wave feminist movement, which began in earnest a decade ago and coincided with the growing popularity of women in other sports. And the wrestling on display was an evolution from the slaps, hair pulling, and derisive use of the term “Diva” that characterized women’s appearances in WWE in the decades prior. Trust that there was no sudden awakening, though. For 40 years, WWE was helmed by Vince McMahon, who has been accused of sexual abuse and is currently embroiled in a sex trafficking lawsuit. Despite the fact that current WWE leaders Paul “Triple H” Levesque and Stephanie McMahon have been congratulating themselves for platforming women’s wrestling, most wrestling fans—40 percent of whom are women—credit progress to star women wrestlers themselves, including Becky Lynch, Charlotte Flair, and Mercedes Moné (known as Sasha Banks in WWE, which she left acrimoniously in 2022). Meanwhile, in the independent wrestling scene, women competitors have been thriving for years—in promotions like Japan’s Stardom, London’s Pro Wrestling EVE (which just crowned its first transgender women’s champion in Nyla Rose), and Chicago-based Shimmer, just to name a few. “Without Shimmer, we might not be where we are today,” says former wrestler and Shimmer manager Allison Danger. “We were able to bring a lot more variety. Having different people from different backgrounds, different races, was making women’s wrestling more diverse.” (Danger is clear to credit past icons, though, “like Mildred Burke, the Jumping Bomb Angels, the Glamour Girls, Madusa, Trish and Lita.”)  THE ICONS WHO PAVED THE WAY, TRISH AND LITA (VIA GETTY IMAGES) The future of women’s wrestling can often be difficult to see because of the long shadow cast by the WWE, a behemoth that seems to only be getting bigger as it aligns with entrenched power. (Levesque has been a frequent visitor to the White House.) The WWE also seems to be getting more shameless: Many fans were turned off by the return of wrestler Brock Lesnar, who is named in the sex trafficking lawsuit against disgraced former WWE chairman Vince McMahon; and WWE has announced that WrestleMania 44 will be held in Saudi Arabia in 2027, even as the kingdom continues to be accused of sportswashing its human rights atrocities. It remains to be seen whether these all-women’s wrestling shows will have staying power. Shimmer has been on hiatus since 2021, and former WWE wrestler Mickie James has experimented with partnering with different promotions—and even different countries—to find the right fit for her all-women shows. It took WWE seven years to produce a second Evolution, despite having all the money in the world and a wealth of talent (most other WWE premium live events are annual). But do these shows need the backing of large companies like WWE? Sure, it would be great to get an annual Evolution, but women like Athena, James, and Danger remain relentless and collaborative, doing the hard work with a fraction of the resources to bring women’s wrestling to fans hungry for it. And they’re optimistic about the future. Danger points to the rise in platforms where wrestling can be consumed (a far cry from the tape-trading days when Shimmer was first launched), and says streaming has democratized the sport. Who Runs the World? streams on Twitch. There’s more opportunity than ever, she contends—and the next generation of wrestlers and promoters will seize it. Says Danger: “We’re in great hands.”  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

The Future of Women’s Wrestling Is Big and Bright in Texas

Welcome to Metroplex

By Scarlett Harris

On the last Sunday in October, in a suburb nestled between Dallas and Fort Worth, Texas, a group of women came together for an all-women’s wrestling show hosted at Metroplex Wrestling, a woman-owned wrestling school. Titled Who Runs the World?, the show was the brainchild of All Elite Wrestling star Athena, and it followed a rousingly successful inaugural show in August; both shows featured some of the biggest names in independent women’s wrestling, including Mercedes Moné, Nyla Rose, and Kris Statlander. A third production is scheduled for January 2026, and will also stream on Twitch.

This sequence of events on the indie scene—three all-women shows in six months!—is a welcome contrast to the mainstream entity World Wrestling Entertainment, which has staged just two all-women wrestling shows in its 70 year history.

Progress for women in WWE has been slow and fitful. Earlier this year, WWE hosted Evolution 2, the much-anticipated sequel to its 2018 show of the same name. In an industry dominated by polarizing macho figureheads like the late Hulk Hogan, both Evolutions were hard-won victories in what we can call wrestling’s second-wave feminist movement, which began in earnest a decade ago and coincided with the growing popularity of women in other sports. And the wrestling on display was an evolution from the slaps, hair pulling, and derisive use of the term “Diva” that characterized women’s appearances in WWE in the decades prior. Trust that there was no sudden awakening, though. For 40 years, WWE was helmed by Vince McMahon, who has been accused of sexual abuse and is currently embroiled in a sex trafficking lawsuit. Despite the fact that current WWE leaders Paul “Triple H” Levesque and Stephanie McMahon have been congratulating themselves for platforming women’s wrestling, most wrestling fans—40 percent of whom are women—credit progress to star women wrestlers themselves, including Becky Lynch, Charlotte Flair, and Mercedes Moné (known as Sasha Banks in WWE, which she left acrimoniously in 2022).

Meanwhile, in the independent wrestling scene, women competitors have been thriving for years—in promotions like Japan’s Stardom, London’s Pro Wrestling EVE (which just crowned its first transgender women’s champion in Nyla Rose), and Chicago-based Shimmer, just to name a few. “Without Shimmer, we might not be where we are today,” says former wrestler and Shimmer manager Allison Danger. “We were able to bring a lot more variety. Having different people from different backgrounds, different races, was making women’s wrestling more diverse.” (Danger is clear to credit past icons, though, “like Mildred Burke, the Jumping Bomb Angels, the Glamour Girls, Madusa, Trish and Lita.”)

The future of women’s wrestling can often be difficult to see because of the long shadow cast by the WWE, a behemoth that seems to only be getting bigger as it aligns with entrenched power. (Levesque has been a frequent visitor to the White House.) The WWE also seems to be getting more shameless: Many fans were turned off by the return of wrestler Brock Lesnar, who is named in the sex trafficking lawsuit against disgraced former WWE chairman Vince McMahon; and WWE has announced that WrestleMania 44 will be held in Saudi Arabia in 2027, even as the kingdom continues to be accused of sportswashing its human rights atrocities.

It remains to be seen whether these all-women’s wrestling shows will have staying power. Shimmer has been on hiatus since 2021, and former WWE wrestler Mickie James has experimented with partnering with different promotions—and even different countries—to find the right fit for her all-women shows. It took WWE seven years to produce a second Evolution, despite having all the money in the world and a wealth of talent (most other WWE premium live events are annual). But do these shows need the backing of large companies like WWE? Sure, it would be great to get an annual Evolution, but women like Athena, James, and Danger remain relentless and collaborative, doing the hard work with a fraction of the resources to bring women’s wrestling to fans hungry for it.

And they’re optimistic about the future. Danger points to the rise in platforms where wrestling can be consumed (a far cry from the tape-trading days when Shimmer was first launched), and says streaming has democratized the sport. Who Runs the World? streams on Twitch.

There’s more opportunity than ever, she contends—and the next generation of wrestlers and promoters will seize it. Says Danger: “We’re in great hands.”

Scarlett Harris is a culture critic, author of A Diva Was a Female Version of a Wrestler: An Abbreviated Herstory of World Wrestling Entertainment, and editor of The Women Of Jenji Kohan.

Just Let Everyone Play

Women’s leagues, men’s leagues, and an all-gender league? A new book explores the possibilities.

By Scarlett Harris

In 1902, British figure skater Madge Syers won the silver medal in what was, at the time, an all-men’s World Figure Skating Championships. Until then, women competed only in elite sports perceived as feminine, such as tennis, croquet, and horseback riding, but weren’t explicitly prohibited from competing against men, perhaps because the thought seemed so outlandish. So in 1906, the International Skating Union created the women’s category, which Syers dominated that year and the next, eventually winning gold at the 1908 Olympics.

Syers is widely credited as the reason a “women’s” category in sports competition came to exist—and eventually became the highly lucrative yet highly underestimated women’s leagues of today. Women’s sports are more popular than ever, with viewership rising and even surpassing the men’s league at times, including at last year’s women’s March Madness. Athletes such as Dijonai Carrington, Angel Reese, and Caitlin Clark are now household names. Women’s soccer is the fastest-growing sport in the U.S. and a far more riveting watch than men’s. But—and stay with me here—are sex-segregated leagues the best we can do for gender equality in sports?

In Sheree Bekker and Stephen Mumford’s thought-provoking new book Open Play: The Case for Feminist Sport, the authors argue that women’s sport isn’t necessarily the ultimate feminist goal we’ve been led to believe it is. “It’s rather a form of segregation and control of women to keep them in their own category so that they never beat men or participate on the same footing as them,” charges Bekker, associate professor of health at the University of Bath.

Sex-segregated sports were created so that “women have a chance at winning based on the assumptions that they could never beat men” and to “keep them physically safe in the case of contact sports,” explains Mumford, a philosophy professor at Durham University. “But it’s not really a protected category; it’s a segregated one. Protected categories exist for the protection of those within those categories, whereas segregation exists for the benefit of those outside the segregated group. In other words, the group benefiting is men. “There’s this fear that one day women might actually be able to catch up to and beat men,” Bekker explains. Hence the reason the women’s category was invented in the first place. (Madge Syers, after all, did just that.)

In Open Play, Bekker and Mumford propose the idea of an egalitarian system where competitors are grouped by weight, power, and ability—rather than sex. There are valid concerns that leagues solely based on weight or power may end up suppressing women’s visibility, since, for instance, with basketball, the format would favor men. Still, if Muggsy Bogues was able to keep up with Larry Johnson there’s no reason Sabrina Ionescu couldn’t keep up with Steph Curry. (After all, she already did.)

Succeeding at sport threatens the patriarchy.

Arriving at a time when right-wing lawmakers are using the idea of protecting women athletes for their own political goals, Open Play is much-needed food for thought. President Trump’s two-sex executive order barred the vanishingly small number of trans athletes in this country from participating in women’s sports. “Trans women are not dominating women’s sport at all,” says Mumford. “It’s a manufactured scare. It’s almost at the point where being good at sport is grounds to question someone’s gender because it challenges the perception of how a woman ‘should be.’ Succeeding at [sport] threatens the patriarchy.”

Consider, for instance, the case of Algerian boxer Imane Khelif, a cisgender woman who had her gender called into question during the 2024 Paris Olympics after her opponent forfeited, chargingthat Khelif’s punches were too hard. Or think of South African runner Caster Semenya, who was made to undergo sex verification testing in 2009. Sex testing in sports appears perennially throughout history, from the “nude parades” of the 1950s and ‘60s to chromosomal testing, which World Athletics just announced it would be reintroducing. “We’re starting to see the reemergence of the idea of ‘who is a real woman,’” says Bekker.

But ultimately, gender policing in sport isn’t just about politics—it’s also about money.

Women’s sports get a fraction of the funding, attention, and visibility that men’s sports do. Without sufficient funding, women are working with subpar facilities, which, as the U.S. Women’s National Team argued during their equal pay dispute, can shorten their careers. Under current women’s-league pay conditions, many women athletes also have to work full-time jobs to supplement their paychecks. While elite male athletes are restoring their bodies to squeeze another winning season onto their resume, women like Ilona Maher are running themselves ragged just to keep the lights on. A theory called the 10% gap, which Bekker and Mumford believe to be flawed, posits that men are roughly 10% stronger, faster, and better at sports than women. But “it’s not as if men’s sport is getting 10% more of the funding than women’s sport,” says Mumford. “It’s usually 90% of funding.” Imagine how much better women athletes could perform if they were given access to the degree of training and resources those dollars can buy.

So, would it work for fans? A modern-day Battle of the Sexes might feel like a feminist win, but the rising popularity and viewership of women’s sports could indicate that some people just aren’t interested in watching men compete, regardless of the gender of their opponent. I am a fan of professional wrestling, and while I’m a champion for intergender wrestling and have written about it widely, I still prefer to watch women’s wrestling only. So while a desegregated athletics landscape might be an ultimate goal—at least as an option—for the time being many competitors would likely choose to stay in their current categories.

Non-binary athletes might offer us a glimpse of a more inclusive future, though. USA Gymnastics doesn’t have a specific category for non-binary competitors, and Australian Athletics offers the option to compete in the binary category they feel most comfortable in. And many nonbinary athletes gravitate towards non-traditional sports like roller derby, in which play is often not sex-segregated.

“Non-binary people are showing us the way forward,” Bekker says. “Traditional sports organizations right now are not on top of this and they’re going to lose more people coming into their sport as younger generations, who are more diverse, grow up.”

In the meantime, we’ll have to content ourselves with sportswomen kicking ass in gendered categories—and waiting for the men to be just as interesting to watch.

Scarlett Harris is a culture critic, author of A Diva Was a Female Version of a Wrestler: An Abbreviated Herstory of World Wrestling Entertainment, and editor of The Women Of Jenji Kohan.

"My Life Has Been on Standby"

February 20, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, It came to my attention this morning that we are pretty much at the end of February. This is terrible news. It’s not that I don’t like March; I’m just utterly unprepared for its two major holidays: Women’s March Madness and Ramadan. Selection Sunday is less than a month away, and I will be hosting another Meteor bracket. My bestie, Em, the Meteor’s reigning champion, will be defending their crown, so start thinking about your picks. Glory and a Meteor tote are on the line.  In today’s newsletter, we are headed to Spain for the verdict in the Luis Rubiales case. Plus, a moment of silence for a four-legged hero, another sneaky attack on abortion rights, and your weekend reading list. Prayin’ and parlayin’, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONCulpado: Luis Rubiales, the former president of the Royal Spanish Football Federation (RFEF), has been found guilty of sexually assaulting Jennifer Hermoso during the 2023 World Cup. As a refresher, during the gold medal ceremony that year, Rubiales handed the medal to Hermoso, grabbed her by the back of the neck, and forcibly kissed her on the mouth in the middle of an international live broadcast. Despite Hermoso’s obvious shock—and her statement that she didn’t like it—the moment was downplayed by the RFEF, Spain’s coach, and eventually Hermoso herself. Accusations of pressure and coercion quickly swirled—in fact, Rubiales was also charged with coercion for allegedly pressuring Hermoso to say the kiss was consensual, though he was acquitted of that charge. At the time, I wrote about the way The Kiss was a visual manifestation of what Spain’s women’s team had endured from RFEF in the lead-up to its first World Cup win—including an oppressive work environment perpetuated by the team’s coach, Jorge Vilda. Vilda and two other employees from the Federation were also charged with coercion but ultimately acquitted. Vilda is now the coach of Morocco’s women’s national team. When I heard the news that Rubiales was guilty, I felt a jolt of happiness that was immediately replaced by the question so many soccer fans and players continue to ask themselves: What will it take to make the beautiful game a safe one for all athletes?  HERMOSO DURING A MATCH LAST FALL. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) While this guilty verdict is a victory, the consequences are small. Rubiales will not be seeing any jail time; his punishment is paying a €10,800 fine and being banned from coming within 200 meters of Hermoso. The verdict is also a drop in the bucket: Abuse is rampant in women’s soccer, everywhere from the international level to U.S. Soccer to youth leagues. It’s taking years—and in the case of the U.S. Women’s National Team, 20 years—for these tiny measures of justice to be handed out, and yet governing bodies refuse to act with the urgency the state of women’s soccer demands. In fact, just four days after The Kiss, the RFEF actually threatened to sue Hermoso and other players on the team who had signed a letter asking that Rubiales be fired from his position. Meanwhile, Jenni Hermoso still has to work under the governance of RFEF and FIFA, which is contending with its own bevy of controversies. Her first World Cup gold is tainted, and what should have been a glorious experience instead links her forever with at man who assaulted her. “I’m a world champion but it seems that even to this day my life has been on standby,” Hermoso told the court during the trial. “I haven’t been able to live freely.” AND:

TOO PRECIOUS FOR THIS EARTH. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

WEEKEND READING 📚On essential data: Rates of sepsis have gone up in Texas since the overturn of Roe. But the state doesn’t want you to know that. (ProPublica) On the money train: There is a way to stop Elon Musk and his made-up job. But it comes with a hefty price tag. (The Intercept) On going under the knife: One of the most dangerous states to give birth in is continuing to give first-time moms unnecessary C-sections. (Mississippi Today)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()