“I wanted to make sure she knew she had autonomy.”

Lulu Garcia-Navarro on interviewing Gisèle Pelicot

by Nona Willis Aronowitz

Lulu Garcia-Navarro, co-host of the New York Times podcast “The Interview,” has covered harrowing circumstances all over the world for the Times, NPR, and the Associated Press. She’s reported on everything from the war in Iraq to the Arab Spring uprisings to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But her recent interview with Gisèle Pelicot, she told me, was one of the hardest she’s ever done.

In our new series, The One Who Got the Story—where we catch up with a woman or non-binary journalist who was behind a major story of the week—we ask Garcia-Navarro how she prepared to interview a woman who endured some of the most shocking sexual abuse one can imagine. Pelicot, whose husband secretly drugged her and invited dozens of men into their home to rape her, made the extraordinary decision during the trial to waive her right to anonymity and allow media in the courtroom. And yet, she’d never truly told her story—until now. On the occasion of her new book, A Hymn to Life: Shame Has to Change Sides, Pelicot, 72, sat down with Garcia-Navarro for her first interview with an American outlet. It’s a sensitive yet unflinching conversation about pain and renewal. Here’s how Garcia-Navarro did it.

I noticed in the beginning of the interview, you asked Gisèle how she’d like you to refer to her rapist (she answered, “Monsieur Pelicot”), and that struck me as a question specifically tailored to someone who’s gone through trauma. What kind of preparation did you do before talking to her?

Because she had never spoken [to the media] outside of the confines of the trial, I didn't know what I was going to get. Some victims of trauma really have trouble articulating their interior life, how they might have felt about things, their recollections of things. So we just prepared by being extremely careful. We made sure that where the interview was going to take place was going to be a very intimate environment. [The crew rented an apartment in Paris for the interview.] The majority of the crew was female. And then I wanted to make sure she knew she had autonomy and she had her voice. [Asking her what she’d like to call her abuser] was a way for me to signal that this was something she had agency over.

You were extremely careful, but you also didn’t shy away from the awful details. At one point you quoted a graphic passage of the book in which Gisèle notices that a crown in her mouth was loose, which she learned later was a result of, as she wrote, “the violence of penises being repeatedly forced into [her] mouth.” Can you explain more about the reasoning to include this?

I know that there's great concern about retraumatizing people and I understand that. I also do feel that sometimes, in trying to protect the victim, we do a disservice to the audience in not really showing the full scope of the horror that somebody went through. I asked for her permission [beforehand]; I said I was going to quote directly from the book, and she said that that was fine. I tried to be as sparing as I could. I just used one line, but it was a line that really haunted me. It said so much about the dynamic between her and her ex-husband, how he gaslit her, how he manipulated her...I felt it was really important for people to know.

You’ve reported amid conflict zones and revolutions, but how does this interview rank in terms of difficulty?

I mean, 100 out of 10. It's one of the hardest interviews that I've done because I think it's just really hard to get right. And if I did, I'm grateful for it. A consistent theme is that people said that they went in bracing for the worst and thinking this was just going to be a tour of horror. What they found instead was her beautiful ability to explain her own experience.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

"This Changes Everything"

February 6, 2026 Happy Saturday, Meteor readers, We’re coming to you with a special treat from the archives today, in honor of the 100th celebration of Black History Month this February. Four years ago, our colleague Rebecca Carroll sat down with author and historian Imani Perry to discuss the surprising origins of Black History Month and its current role in the American story. When we first published this piece, we noted that legislators were trying to strip Black history lessons from school. Some of those efforts are now law, but advocates, educators, and avid readers remain undeterred. And I suppose that’s the history lesson in and of itself—the harder you try to erase it, the stronger it becomes. Love and power, Shannon Melero  “This Changes Everything”What Imani Perry taught me about Black History MonthBY REBECCA CARROLL  THE INCREDIBLE IMANI PERRY WAS HONORED AT THE 2025 WOMEN'S MEDIA CENTER FOR HER BODY OF WORK (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Years ago, when I was working at a mainstream media corporation, I was called into a marketing meeting for my ideas on how to best package Black History Month in ways that would boost ad sales and sponsorship on the site. I suggested, in all seriousness, because I genuinely believed what I was saying: "What if we didn’t package Black History Month at all? What if we took a break from selling this idea that Black History is something we should only think about for a month every February?" I was promptly dismissed from the meeting. The thing is, I was coming from a place of profound (and uneducated) cynicism, based on the belief that Black History Month was created by white folks. And I know I’m not alone in thinking this. Thank heavens for historian and author Imani Perry, whose book, South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation, covers this terrain, and who went ahead and set the record straight for me—because honestly, I simply did not know. Rebecca Carroll: Given that I was adopted into a white family, raised in a white town, and then went on to spend the bulk of my career in white media spaces, Black History Month has always seemed exploitative and commercialized to me—but I was so curious to learn from you that Black History Month actually has its origins in Black culture. Can you explain? Imani Perry: Black History Month was an outgrowth of Negro History Week. In the early 20th century, Black history programs and curricula were organized in segregated Southern Schools. They happened in February because that was the month of Abraham Lincoln's birth and Frederick Douglass's chosen birthday (he didn’t know his exact birthdate, having been born in slavery). In 1926, historian and organizer Carter G. Woodson formalized these practices and established Negro History Week [in February].  A COLORIZED PORTRAIT OF CARTER G. WOODSON, THE FATHER OF BLACK HISTORY MONTH (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Negro History Week was an extension of a very deliberate effort that began immediately post-emancipation to document Black history…and resist the false claim that people of African descent had contributed nothing meaningful to human history or civilization. Negro History Week, which became Black History Month in the early 1970s, was focused on young people…and became a robust tradition. There were Negro History Week curricula—books on Black U.S., Caribbean, and African histories and historic figures; essays, documents, plays, pageants, and academic exercises along with the ritual singing of "Lift Every Voice and Sing." Often, these school-based programs invited the entire community to participate, and so these were collective celebrations, as well as opportunities for people to learn. It wasn’t really until the late 1970s that white Americans even began to have any significant awareness of Black History Month, and much of that came through consumer culture. So, [as with] Kwanzaa, a ritual that was developed primarily within Black communities made its way to the larger public through advertising strategies intended to compel Black buyers rather than [achieve] substantive political transformation. So we get fast food companies celebrating Black History Month in ways that mean close to nothing or, at times, are even offensive. But despite that, there continue to be institutions in which Black History Month is rooted in a tradition of Black people writing themselves into history in ways that reject the logic of white supremacy and give a more expansive reach to the story of Black life both in this country and globally. And so what does Black History Month mean to you, both personally and professionally? Personally, Black History Month is one of those traditions, like Emancipation Day or Juneteenth or Watch Night, that I cherish because it anchors me in tradition and ritual. Professionally…because I’m very invested in ensuring that my students know the history of Black institutional life, I teach the ritual as an outgrowth of one of the most important periods of intellectual development in African American history. Traditionally, historians describe the Jim Crow era as the "nadir" of American race relations, the phrase used by historian Rayford Logan. And by that, he meant the lowest point, that horrifying period when the promises of Reconstruction had been completely denied. What is remarkable about that time is that Black people got to work despite the devastation. There was exceptional growth in African American civic life in this period. People were building organizations and networks, writing books and developing social theory, building schools, and churches at every turn. And so, even when society shut the door to opportunity and treated Black people with horrible brutality, they kept dreaming, doing, and creating. For me, that is not just a key point for understanding African American history, but it is an incredible daily inspiration for my own work. Do you think it's ever more necessary in this current cultural climate to uphold BHM, and if so, to what end? I don’t think of Black History Month as more or less important based on the political moment. I guess I would say it will be important indefinitely because we live in a white supremacist country and world, and counter-narratives that value freedom and dignity and resilience will always be necessary as long as stratifying people on the basis of identity is the norm. Surely you’ve had experiences where (almost always white) people will say something that is just all kinds of wrong regarding BHM—I’m sorry to say I have had several—or there is this unspoken sense of "We’re giving you this whole month, can you just be grateful?" Can you recall such an experience, and how you responded/flipped the script for your own sense of sanity? Thank goodness I've never had a white person say to me that they’ve given Black people Black History Month. It would frankly be something that I'd laugh at for a long time. Nothing could be further from the truth. Black people created it for Black people, and particularly for Black young people, and have been gracious enough to invite others to participate. They should feel fortunate.  ENJOY MORE OF THE METEOR Thanks for reading the Saturday Send. Got this from a friend? Don’t forget to sign up for The Meteor’s flagship newsletter, sent on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()

A Bigger, Badder, Bunnier Bowl

February 5, 2026 Hey there Meteor readers, Nona and I both woke up this morning with fevers and intense cases of the daycare schmutz. So this newsletter is brought to you by Tylenol, Ricola, and some nasty-ass ginger tea.  Today, we’re going full Sporty Spice with some emotional prep for Bad Bunny’s halftime performance this weekend. Plus three questions about what athletes are facing at the Winter Olympics. Achoo 🤧, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONDomingo Gigante: Last weekend, during his Grammy acceptance speech for Album of the Year, Bad Bunny opened with a vastly underappreciated line: “Puerto Rico, créeme cuando te digo que somos mucho más grandes que 100 por 35.” If you haven’t gotten your Duolingo minutes in today, that’s “Believe me when I tell you, we’re so much bigger than 100x35,” which are the land measurements of Puerto Rico’s main island. The rest of his message, delivered mostly in Spanish, touched on perseverance. But the idea of being bigger is what’s stayed with me these last few days, particularly in a political moment where the best thing anyone can be is unseen. Unseen by ICE agents lingering in train stations. Unseen by trigger-happy police officers. Unseen by right-wing extremists. Stepping out of my house every day, my greatest desire is for my family to go completely unnoticed and make it back safely. But throughout his career, Bad Bunny has defied the idea of being small, of asking permission to enter a space as his authentic self. He just shows up. He simply is, and he does it loudly, boldly, and sometimes in a fabulous gown. He’s done so in a way that his musical forefathers—DY, Marc Anthony, Tego Calderon—never could because they were either trapped in the Latin music gilded cage, or chose to avoid politics until much later in life. For all their fame, they were also kept smaller by (mostly) American audiences and an industry that sees Latin music and people as separate from the American identity. But in the words of another great, Residente, “América no es solo USA, papá.”  HOW WE'RE ALL ABOUT TO BE SMILING THIS SUNDAY. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Of course, the ability to make yourself more or less visible is rooted in privilege. White and light-skinned artists can take a step back *cough* JLo *cough* in a way that protects them from the ire of entire administrations. After all, Turning Point wasn’t running counter programming in 2020 when JLo and Shakira headlined the halftime show. Conservatives did, however, have a ton to say after Kendrick Lamar’s performance last year. (I guess a Black, California-born Pulitzer Prize winner just isn’t American enough?) And despite making no noise over Green Day, who are performing on Sunday as well and have an entire album devoted to political criticism, conservatives have been spending the last few months proselytizing about how un-American it is to have a Spanish-language artist take center stage at the Super Bowl. (Let’s all be honest with ourselves for a minute, y'all don’t want most of these songs translated. I promise you chocha is not going to hit the same in English.) Which is why Bad Bunny’s choice to use his privilege to step into the fray rather than avoid it is so important. His pride is not a performance piece he takes on and off when the mood suits—and that kind of authenticity encourages others to walk in pride. It’s bigger than a 15-minute set we won’t remember a year from now. It’s bigger than 100x35. It’s a call to know who you are—your history, your symbols, your land, your people—and to stand tall, whether or not you are acceptable to the powers that be. Especially when you’re not. AND (promise a sports break):

PENNY THE DOBERMAN PINSCHER, THIS YEAR'S BEST IN SHOW. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)  Three Questions About...This Year's Winter OlympicsThe trailblazers to watch and the ICE of it all.BY SHANNON MELERO  LAILA EDWARDS (FRONT, BLUE) AND TEAM USA HOCKEY FACED OFF AGAINST CZECHIA THIS WEEK, AND SECURED THEIR FIRST WIN OF THE GAMES. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Jamie Mittleman has the kind of job that, if it were explained in a Netflix rom-com, would sound entirely made up: She talks to Olympic and Paralympic athletes all day. Fine, it’s more than that; she’s the CEO and founder of Flame Bearers, a media company centered around women Olympians and their stories. But the fun part of her job is working with athletes and traveling to the Games. The summer Olympics usually get all of the shine, but this year, the roster for Team USA is, as I think the kids say, bussin’. Two-time gold medalist Chloe Kim is back chasing a third podium. Figure skater Alysa Liu is out of retirement at the ripe old age of 22 and skating better than ever. Lindsey Vonn plans to compete on a totally destroyed ACL (girl, please don’t do that) and, of course, we’re all ready to get our Heated Rivalry on and cheer for the women’s ice hockey team captained by the incomparable Hilary Knight. Ahead of her travels to the Milan/Cortina Olympics, Mittleman took some time to talk to us non-Olympians about what to expect. The Olympics have always had political undertones. As someone working closely with so many women athletes ahead of Milan/Cortina, are there themes you’re seeing pop up? A major theme I’m hearing from athletes is access. Who gets into winter sports? Who can afford it? Who sees themselves in it? Winter sports remain some of the least diverse athletic spaces in the world, and athletes are acutely aware of that. They talk about the cost of equipment – how expensive is a ski pass? Hockey gear? A bobsled? [Plus] the lack of local facilities. Do they have to drive to get to the track? What if they don’t have a car? Nobody from my community competes in this sport…and how all of these compound over time. There’s also a strong thread of athletes wanting to use their visibility to widen the doorway for the next generation. I’ve now worked with just shy of 400 Olympians and Paralympians from 55 countries, and many are navigating being “firsts” in their sport—first from their country, first openly queer, first Black athlete in their discipline. They’re proud, but they’re also very aware of the weight of representation they carry. It’s a privilege, but it’s also a responsibility they didn’t necessarily sign up for. Speaking of firsts, Team USA has two major ones on the roster this year with Amber Glenn, the team’s first openly queer figure skater, and Laila Edwards, the first Black woman to play ice hockey for the U.S. What are you hoping viewers can take from watching them compete?  EDWARDS AT A WELCOME EVENT IN MILAN MAKING BLACK HISTORY DURING BLACK HISTORY MONTH. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Seeing Amber Glenn and Laila Edwards on this stage matters far beyond medals. I hope young viewers see that there is no single mold for who belongs in sport. In her "Making It To Milan" interview, Hilary Knight mentioned, "There is a place for everyone in sport.” You can be openly queer and compete at the highest level. You can be a Black woman in a sport that has historically excluded you. You don’t have to shrink yourself to fit into a system. For many young people watching, this may be the first time they see someone who looks like them, loves like them, or comes from a background like theirs on Olympic ice and snow. That moment of recognition matters. It’s often the first spark of belief: Maybe I belong there too. That belief is why my company exists—to make it clear that you do. It’s also important to mention that just as many “firsts” exist in the Paralympics, which begin immediately after the Olympics—and I highly recommend tuning in. We recently learned that ICE is also going to Milan with Team USA—which as an Olympic fan, fills me with embarrassment during a time I’d normally be feeling a rare moment of national pride. Does that change the viewing experience for you at all? ICE traveling with the U.S. delegation is fundamentally at odds with the spirit of the Olympic Games, a hollow stunt of performative power. While hidden under the guise of ‘protection’, this move reads less as a safety measure and more as a PR maneuver—an attempt by the Trump administration to reclaim international relevance and authority at a moment when the US is increasingly isolated and losing credibility. Coming on the heels of Davos, where international leaders such as Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney signaled clear resistance to Trump’s agenda, ICE’s presence is an attempt to project strength at a time when US influence has clearly decayed. Outside the US, the context is very clear: ICE is not relevant, nor wanted. The International Olympic Committee has said their presence is ‘distracting and sad.’ The Mayor of Milan explicitly said they are not welcome. Since the announcement of their presence, several organizations have moved to disassociate from the word “ICE.” The Milan hospitality suite, once called the “Ice House” has already been renamed. [But their presence] reinforces why the athletes’ stories—and their humanity—matter even more. The athletes are showing up to compete after lifetimes of work. This is about them. Their journeys. Many come from immigrant families, from underrepresented communities, from places where sport was their pathway to opportunity. The geopolitical backdrop is real, but what I see up close is athletes trying to hold onto the purity of why they do this in the first place. You can listen to Flame Bearers' full Making it to Milan series here.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

The Formula for Equal Parenting

February 3, 2026 Greetings, Meteor readers, I made croissants this weekend. From scratch. I’m not saying that I’m better than y’all now, but I am typing this with my nose up a little higher than usual.  In today’s newsletter, Nona Willis Aronowitz upsets all the granola moms. But before that, we take a look at the DOJ’s latest blunder. Butter fingers, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON“Indefensible”: Like manna from the depths of hell, another bundle of Epstein files was released to the public last Friday, six weeks later than promised. The drop included millions of documents and redactions to the nth degree, but as we quickly learned, not everyone got the same level of black-box protection. The New York Times first reported that the DOJ published several images of naked women, some of whom may have been teenagers, while covering the faces of Donald Trump and other unnamed men who are seen in photos with well-known figures (Steve Tisch, Elon Musk, and Casey Wasserman, to name a few). As ABC News reported over the weekend, names of and identifying information about victims that had not previously been made public were also exposed in this drop. The images were later corrected after the Times alerted the DOJ to the errors. But, for those whose names and identifying information were left unredacted for hours on Friday, the damage had already been done. Lawyers representing over 200 accusers requested that the documents be taken down altogether so the DOJ could redact the documents properly. Another group of survivors released a statement, which reads in part, “This is a betrayal of the very people this process is supposed to serve. The scale of this failure is staggering and indefensible.” It couldn’t be any clearer who the DOJ truly wants to protect, which is probably why survivors are calling on Attorney General Pam Bondi to answer for these failures when she appears before the House Judiciary Committee on February 11. What happens now? According to Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche, “There’s a lot of horrible photographs that appear to be taken by Mr. Epstein or people around him,” he said, “but that doesn’t allow us necessarily to prosecute somebody.” He also added that with the release, everyone could check the documents themselves and “see if we got it right.” My law degree from the academy of Dick Wolf Productions doesn’t exactly qualify me to double-check the work of the Department of Justice, but it’s safe to say that telling victims to DIY their own cases against the richest and most powerful men in the country is a non-starter. Meanwhile, Bill (who appears in several photos in the latest files) and Hillary Clinton have agreed to testify before the House Oversight Committee. It will come as a surprise to absolutely no one if, after their testimony, the DOJ suddenly decides prosecuting Trump’s biggest enemy is a top priority. AND:

A Feminist Love Letter to Baby FormulaIs it the key to a more equitable partnership? The Meteor’s Nona Willis Aronowitz makes the caseBY CINDI LEIVE  NONA'S PARTNER, DOM, AND THEIR TWO CHILDREN. (PHOTO COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR) Two days ago, in The New York Times, my colleague Nona tossed a lovingly crafted, deeply researched grenade into one of the more passionately held beliefs about parenting: that breast is best. The title of her piece, “The Secret to Marriage Equality is Formula,” argues exactly that, but it goes further—Nona argues that formula (often a source of raised eyebrows in feminist circles for some very good reasons) can also be the secret to less stress and happier parenting for women in or out of partnerships. The piece struck such a nerve that the comment section is now closed. But after breast-feeding two babies myself, and feeling guilty whenever I used formula, I had questions. First off, for those who didn't read the piece, how did you personally discover that the secret to marriage equality is baby formula? I discovered this the hard way. The first time around, with my daughter Dorie, I breastfed because it seemed like the default: Everybody assumes that if you can breastfeed, you should breastfeed. While breastfeeding was a very nice way to bond, the experience was also very intense: It led me to desperately want to control the feeding realm. I was learning so much about her, which led me to push my partner, Dom, out of the space (he didn’t exactly argue—socialization runs deep!). Meanwhile, I was sleep-deprived, isolated, and resentful. I felt like I hadn’t signed up for being Mom-In-Chief with a hapless underling as a co-parent. My husband and I fought constantly, which wasn’t good for any of us, including the baby. So, when we had a second daughter, Pearl, we figured we should try to prioritize equality, even if it undermined breastfeeding. It seemed like a small price to pay for a harmonious experience, and for my baby to genuinely have a wonderful bond with her father from the get-go. And you know what? It worked almost instantly. I breastfed exclusively for two weeks just to establish breastfeeding, and it was like PTSD—all of the bad feelings came flooding back. But as soon as we started introducing formula and Dom started doing overnight feeds, the vibe in our household totally changed.I felt so much closer to him, I felt so much happier to see my baby in the morning, and he really learned Pearl in a way that he didn't learn Dorie until she was a toddler. As we used more formula and bottles, he was just as good at soothing the baby as me. The comments on your piece are copious and mostly very positive, from women saying thank you, we should have options. There were two other strains of responses I wanted to ask you about. First, from people who say: Just pump! And second, from people noting that the scientific evidence shows that breastfeeding is medically superior. Let’s start with the idea that pumping breast milk could solve the equal parenting issue.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

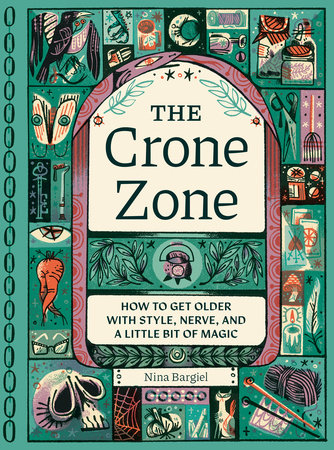

Three Questions About...Embracing Your Crone Era

It’s a thing, says Nina Bargiel.

BY BRIJANA PROOKER

In the age of Ozempic and deep plane facelifts, in which every outward sign of aging is reversible as long as you have the luxury of money, author Nina Bargiel has a revolutionary idea: Embrace your crone era. It’s a spooky concept, particularly post-2020, when staring at our faces over Zoom prompted a plastic surgery boom, pushing us past body positivity and even body neutrality, all the way into mainstream body hate. But it’s Halloween, the perfect time to honor our wisdom and warts.

In THE CRONE ZONE: How To Get Older With Style, Nerve and a Little Bit of Magic, children’s TV writer Bargiel, 53 (who famously wrote the bra episode of Lizzie McGuire), uses the triple goddess concept to answer a key question: what's a crone (AKA any woman over 35, according to my Instagram feed) to do? “Fuck it,” Bargiel writes.

You’re a self-declared crone in your 50s. How would you describe “crone” for the modern era?

So Baba Yaga has always been my bitch. Baba Yaga is the [Slavic] crone who has self-selected herself into the woods. She lives in a hut atop chicken legs. She has a terrifying fence made of human bones. When a traveler gets lost and knocks on her door, sometimes Baba Yaga eats them. And my thought is, this woman has given every indication she does not want to be bothered. So if you’re knocking on her door, and she ends up frying up your liver, you kind of deserve it, because she has made it very clear: leave her alone.

For me, a crone is a woman who is sick and tired of making herself small to make other people feel comfortable. I refer to it as when your inner “fuck you” becomes your outer “fuck you.”

In your book, you say, “Whether gracious grandmother or wicked witch, the crone is always cast as a woman whose best days are behind her.” What are we getting wrong about how we understand crones?

The crone is overlooked and looked down upon, yet the crone is filled with magic. It’s funny because society [says] you're invisible and you're useless. But [crones also] have wisdom and power. If you think about Shakespeare and Macbeth and the three witches, I mean, they're terrifying. Like, they are hags, but they will mess you up. And I will say, [the definition of] “older women” keeps getting younger by the day. I was talking to a woman at one of my [book] signings…about my crone book, and she was like, “I need this because people are treating me this way.” She's 28 years old.

I love your crone touchstones: “Wisdom, to know who we are, Knowledge, to understand what we want, and Fuck It, to do what we please.” What does “Fuck It” mean to you?

[As a woman in a male-dominated writer’s room], you’ve got to be nice, you’ve got to get along. I played that [role] for a long time, and I discovered that it didn't get me any further. I would bite my tongue, and then these men wouldn't hire me again anyway. So why was I biting my tongue? I might as well just be 100% who I am.

When COVID hit, and I had a divorce, and the entertainment industry was taking a bad hit, I just got sick of pretending everything was fine all the time. I sold my house [in Los Angeles] and moved in with my parents [in Illinois] and got a job working in the cheese department at Whole Foods. And there are people who are like, “You shouldn't say that because people won't take you seriously as a writer.” If people don’t take me seriously as a writer, after 25 years, after two Emmy nominations, after two Kids’ Choice Awards and a Gracie Allen Award, they were never going to take me seriously. So my Fuck It is, if you look at me as lesser because I'm part of the labor force, then I feel sorry for you, because life's gonna hit you hard.

Another part of Fuck It is I am 53, and my boyfriend just turned 35, so he is 18 years younger than I am, and fuck it, I don't care. There are a lot of people that have said a lot of things, and by the way, they're mostly men. Almost every woman, when they find out, are like, “Oh, good for you, sister.” If someone's gonna try to shame me for that, fuck it.

Women cannot build a hut atop chicken legs or have a fence made of human bones [like Baba Yaga]. But we can wear headphones. We can have all of these things that say, “Do not bother me,” and yet the travelers, who are usually men, still come knocking at our doors. Unfortunately, we cannot fry up their livers, but we do not have to entertain whatever it is they have to say.

Brijana Prooker is a Los Angeles-based freelance journalist and essayist covering health, gender, and culture. She's a proud pit bull and cat mama whose work has appeared in ELLE, Washington Post, Good Housekeeping, and Newsday.

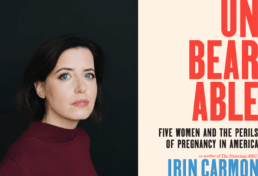

The Complex Landscape of Pregnancy in America

A new book dives into what the experience is like—and why

By Rebecca Carroll

If you’ve ever been pregnant (to term or not), you know that suddenly your choices are of public interest, and sometimes outright judgment. Pregnancy is a deeply personal experience that also inescapably involves power, vulnerability, politics, and a litany of unjust systems built for only certain beneficiaries. In her latest book, Unbearable: Five Women and the Perils of Pregnancy in America, journalist Irin Carmon weaves together narrative stories and reporting to create a lucid, sometimes heartbreaking, chronicle of how pregnant people are guided, or too often misguided, to navigate the experience in America.

Rebecca Carroll: I want to start by asking about something you wrote in the book’s introduction, which is that “being pregnant in America means bearing the consequences of separating one form of reproductive care, abortion, from everything else.” What is “everything else,” and what do you mean?

Irin Carmon: All other forms of reproductive medicine—prenatal care, birth, infertility, pregnancy loss—or even gynecological care in general. Before the white male takeover of medicine [in the mid-19th century], all reproductive care [including abortion] was more integrated into communal life, really across cultures. It was a group of women who were surrounding somebody at different stages of their reproductive life, from the onset of menarche through pregnancy and childbearing. I’m not saying that that system was perfect or that the old way was the right way, but I was really struck reading the history of the first abortion bans—as we live under the yoke of the new abortion bans, which are even more draconian and enforced with much more efficacy—that abortion bans and the white male medical establishment takeover of medicine were inextricably linked to each other.

It struck me as one of the many original sins of [modern] medical care. The other one being that the foundation of contemporary gynecology and obstetrics was American enslavement, and the unjust experimentation on enslaved women.

The part about experimenting on enslaved Black women was really hard to read—I actually physically winced. I think the narrative around childbearing and -rearing for Black women in America is so fraught, from the brutal, harrowing reality of how it all started with enslaved Black women, to the way that Toni Morrison used to talk about mothering as this gift of being able to keep and mother our children. How did you reconcile the different ways that Black women and white women experience pregnancy care?

Dr. Yashica Robinson [an Alabama-based OBGYN and former abortion care provider] was actually one of the starting points for me wanting to write this book. In so many ways, the work that she does is the embodiment of what could be a better way. I first met her in 2014 when I was reporting for MSNBC, and I had come to interview [her husband], who ran the only Black-owned clinic in Alabama. Dr. Robinson walked into the room, and when she started talking, I thought, “Who is this? Did I come to interview the wrong person?” I thought, this is the person who I want to learn from, and to help me understand the truly bifurcated, painful dichotomy you are talking about. Another Black woman I write about in the book, Christine Fields, died in the same hospital as Maggie Boyd, a white woman I also write about. They were both harmed by the same doctor. But…Maggie was able to come home and raise her son because when her husband screamed for help, he was listened to. And when Jose [Christine’s husband] screamed for help, they called security on him, and wouldn’t let him be in the room.

They left Christine alone, maybe because she was being treated like a problem, [and] we know from the research that Black women are much more likely to be treated in medical settings as a problem when they question the treatment or the care that they’re getting.

When I had an abortion in the 90s, even though I didn’t hesitate, I still felt so much shame, in no small part because of the picketers outside the clinic calling me a murderer. Where do you think shame falls today in the broader conversation?

The shame of being a “bad mother,” whatever that means to the person uttering it, is very powerful. And the anti-abortion movement has done a very effective job in making people—even when they’re feeling a sense of relief, which is the most commonly cited feeling around an abortion—feel shame for being a “bad mother.” I write about the work of Lynn Paltrow [founder and executive director of Pregnancy Justice] and Dorothy Roberts [civil rights scholar and author of Killing the Black Body] in the book, and I think they have so powerfully shown how this shaming of pregnant people’s very existence is so malleable that it can encompass somebody with a substance abuse problem, as well as somebody who drinks a glass of wine. Everybody thinks, “I won't be the person whose behavior is scrutinized.” [But] the post-Dobbs era has made clear just how broad the tentacles of policing pregnancy can be.

How has your own pregnancy experience been impacted by the stories and experiences you write about in the book?

I was postpartum when I read about Hali Burns getting arrested six days after her son was born; she was arrested in her son’s hospital room. And so I’m mindful of the fact that I’ve been incredibly lucky, but that I feel a sense of deep connection to these women [in the book]. The work of this book was in trying to go deeper to understand the factors in the systems that led us to any given situation, because I’ve been the recipient of some low-key shitty pregnancy care, and I’ve had some incredible pregnancy care. For people who choose to go down this path, everybody deserves to have access to what I had access to.

“I saw a photo and my heart just dropped”

|

Good evening, Meteor readers, I’ve just stepped off a plane from Vienna, so I’m jet-lagged and 40% pretzel. Tonight’s newsletter is even saltier, featuring upcoming election news, Malala Yousafzai’s new memoir, and a powerful conversation between The Meteor’s Rebecca Carroll and Deesha Dyer, who was the White House Social Secretary during the Obama administration and worked out of the now-demolished East Wing for much of her tenure. Let’s get to it. Mattie Kahn and The Meteor team  WHAT'S GOING ONThis week, President Trump took a literal wrecking ball to the East Wing of the White House and referred to its demolition as “the beautiful sound of construction.” But this was an historic space, with a legacy that meant something to a lot of people. (It has housed the office of every First Lady since Eleanor Roosevelt, for starters.) Several Democrats have pledged to investigate Trump’s “renovation,” and the public wants answers. In the meantime, though, those who worked in the East Wing are grieving—including former White House Social Secretary Deesha Dyer, who held that job during the last two years of the Obama administration. To get a sense of what this moment means, Rebecca Carroll called her.  DEESHA DYER WITH THE OBAMAS (COURTESY OF THE OBAMA WHITE HOUSE) Rebecca Carroll: It must feel so surreal to have been part of the first Black presidential administration in the White House, and to experience this demolition in real time—can you put that into words at all? Deesha Dyer: I can’t. It’s hard, Rebecca. I’ll be honest with you, because right now we’re having so many fights on so many other fronts. This morning I was helping a family get food and find housing. I avoided the photos [of the East Wing] and the conversations, because right now I need to focus on the basic needs of people. And then I saw a photo, and my heart just dropped. It affected me more than I thought it would. Because what we see, as one of my colleagues said, is a metaphor for everything happening right now. The destruction of the East Wing is a destruction for so much of what’s happening in our neighborhoods, in our communities. And as hard as it is going to be to ever rebuild the East Wing back, that is how hard it’s going to be to rebuild everything back. RC: Can you imagine a scenario in which President Obama would ever have been like, “I’m going to demolish…anything”? DD: No. He couldn’t even wear a tan suit. You know what I mean? I remember we had an event doing yoga in the East Room of the White House, and it was like, “Can we do that? Is it okay to lay yoga mats down on this historic floor?” Anything that we did, we did with extra scrutiny. I can’t even imagine if President Obama had cut down a bush outside of the White House. It would’ve been: “How dare you do this to America? You’re desecrating the country!” RC: You noted on Threads this week that three Black women have run events in the East Wing, including yourself, and you ran those events for the first Black First Lady. How symbolic does it feel that Trump chose the East Wing to demolish? DD: Very symbolic. That’s where the First Lady’s office has always been, and so it symbolizes what he thinks about women in general—and women in power specifically. The East Wing is also where people enter for tours and celebrations and all types of events. So it also says a lot about what he thinks about opening up the house, and making it really the people’s house. ... This is a property that is paid for by taxpayers. It is the people’s house. So it is not his. RC: And did you and the former First Lady ever have any conversations about the significance of the East Wing? DD: Definitely. All the time. Mrs. Obama talked to the entire staff about what her vision was for the East Wing and the White House. She always wanted to make it so it felt like everybody’s house. We made sure that from the minute you stepped in the door, you felt like this is a place that considered who you were, whether it was your culture, whether it was your family, whether it was anything. It’s jarring to see that all just gone. RC: What does that space mean to you personally? DD: I’m a Black girl from Philly—a hip-hop writer who had a community college education. I was also in charge of bringing to life the vision of Mrs. Obama and President Obama. And so for me, the space means possibility and hope. And we know that the history of the White House is not all grand. We know the implications of it being built by slaves. But we did our best to make sure that people saw themselves in it. That yes, our ancestors built the building, but we can dance in it. We can have joy in it. We can have our art in it. We can have our music in it, and be happy about that. RC: How are you taking care of you right now? DD: I’ll keep it a buck, I’m not. I’m constantly thinking, “This is terrible. This is a mess.” I’ll be on a walk with my husband and get a call about a food bank or a family in need. And so it's hard to take care of myself at this time. But I have to remember that I am a Black woman in this country that is a product of systems. I have type two diabetes and high cholesterol and high blood pressure. And so the system is also trying to kill us softly while it’s trying to kill us fast too. I need to continue going to therapy and taking my medicine and encouraging other people…. I’m not probably doing the best I could taking care of myself, but I’m trying.  THIS WEEK'S DEMOLITION OF THE WHITE HOUSE'S EAST WING (GETTY IMAGES) AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

A First Step Toward the Future

October 14, 2025 Fair Monduesday, Meteor readers, It’s going to be a dark week in our nation, and not just because the fall weather is finally settling in. This week, a powerful, malevolent force is convening. We are, of course, referring to the Moms for Liberty Summit in Florida, which kicks off in two days.  In today’s newsletter, we consider what’s missing from peace negotiations (hint: it starts with a W). Plus, two former editors-in-chief take the shame out of being shitcanned.  WHAT'S GOING ONA first step toward the future: Last week, the world breathed a sigh of relief when Israel and Hamas accepted a ceasefire agreement that would see the release of both Israeli and Palestinian hostages and allow aid to enter Gaza. As expected, Donald Trump took much of the credit for the agreement. But after a weekend of families reuniting with their loved ones, news broke this morning that Israeli soldiers had already shot and killed at least nine Palestinians who were returning to their homes in Khan Younis. This is, unfortunately, a familiar situation—a ceasefire announcement, a brief moment of joy, a ceasefire violation, and then a renewed cycle of violence. But as more nations publicly demand an end to the genocide, there is a growing hope that this time will be different. And it must be different. Over the last two years, more than 67,000 Palestinians have been killed (although the UN believes this may be an undercount), and more than half of those killed were women and children. Yet despite the disproportionate impact the conflict has had on women and children, peace negotiations and planning for the future have been led almost entirely by men. This isn’t exactly a surprise considering the makeup of the governments involved, but it is, as history has shown us, a failing strategy. Earlier this month, the United Nations commemorated the 25th anniversary of Resolution 1325, which urged leaders to “increase the participation of women and incorporate gender perspectives in all United Nations peace and security efforts.” “Where women lead, peace follows,” Sima Bahous, the executive director of UN Women, said in a speech to the Security Council. (Data backs her up: Peace is 35% more likely to last 15 years or more when women are at the negotiating table.) In this moment, where over 600 million girls are living in zones of conflict worldwide, it seems like the right time to try a different approach. Click here to learn how you can support aid and rebuilding efforts in Gaza. AND:

ALL THEY DO IS WIN. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

Three Questions About...Getting FiredNo shame in getting shitcanned, say Laura Brown and Kristina O'NeillBY CINDI LEIVE  TWO COOL FIRED GALS (COURTESY OF GALLERY BOOKS) Getting unceremoniously sacked has always been an occupational hazard for magazine editors; back in the 1980s, Vogue’s Grace Mirabella reportedly found out she’d been let go when she heard it on the TV show Live at Five. But when it happened to Laura Brown (the former head of InStyle) and Kristina O’Neill (of WSJ Magazine), they eventually realized that, to quote Nora Ephron, everything is copy. These two friends (and, full disclosure, friends of mine) sat down to write a book about the experience: All the Cool Girls Get Fired, in which everyone from Oprah to Carol Burnett tell their own pink-slip stories. It couldn’t be better timed. Earlier this fall I ran into an acquaintance on the subway and was telling her about the book. We noticed a woman next to us leaning close. “I”m sorry,” she said, “would you mind saying the name of that book again? I need it.” In case you do too, here are three questions for the authors. My first question is, the book is All the Cool Girls—not all the cool boys—Get Fired. So I'm curious—how is the experience of getting fired for women different than it is for men? Obviously it happens to them too. Kristina O’Neill: We noticed that there was a universality around the shame and the embarrassment and the disappointment that women respond to this sort of life event with. We noticed that a lot of men, if it has happened to them, it almost becomes part of their armor and part of their narrative—I mean, Steve Jobs, Mike Bloomberg, they made getting fired part of their entire work journey. Whereas when we sat down to write this book, we couldn't easily identify women who, after having been fired, owned it. It does seem like women have a harder time just saying what happened to them and moving on psychologically. Laura Brown: I asked [human resources pro] Bucky Keady: Why does it hit so much harder [for women]? And in one second she said, “Because it took so much longer to get there. It took us so much longer to get into that room.” So many of us feel shame and wallow. But it’s futile. And you have a community, but you're not going to find the community unless you put your hand up: Actually, me too. That happened to me as well. And then, God, that's a help. That's such a relief. But you have to speak up. Whose story of being fired surprised you, or made you see their career differently? KO: We were really struck by how many women hadn't talked about it before. Katie Couric, for example, kept saying, Well, they didn't renew my contract, and it was almost like a revelation in the conversation when I think it sort of dawned on her, like, Yeah, I guess I was getting fired! We [also] talked to a sports agent, Lindsay Colas, who’s brilliant and who literally got Brittney Griner out of prison in Russia, and another client called her after she got Brittney out of jail and said [something to the effect of], “You haven't been paying enough attention to us, we're going to go with a different agency!” So fired looks different for everybody: the language around it, the experience, the aftermath. But the universal thing is you feel like shit. LB: One of my favorite stories was from Tarana Burke; she was running an organization in Philly and she was comfortable there. Then she got fired. And in all this time, me too was sort of lying dormant in her head. So when she was fired, she was then allowed to open her mind to proceed with that. She said, I kept thinking, You've been carrying other people's visions to fruition for too long. And she was able to carry her own. How much did you know about Oprah’s firing [from her job as co-anchor of the Baltimore evening news] before interviewing her? LB: We knew the story a little, but again—it wasn’t the [big narrative] about her. She should be on the fired Mt. Rushmore with Steve Jobs and Mike Bloomberg and everyone else! When we talked to her, her memory of the firing was like muscle memory. It was so visceral. [“I really have never talked about it,” says Oprah in the book.] She remembered what the managing director of the TV network was drinking. She remembered it was April Fools’ day, and she thought it was an April Fools’ joke. Bang, bang, bang, bang, bang, she remembered all these things because sadly—it's almost like with Instagram comments when you remember the negative one and you forget all the nice ones. And Oprah got upset about it anew, but she was us. She was ashamed to tell her dad, she was ashamed she lost her job. But her story reminds you that [getting fired] fires up your dreams too. KO: If it hadn't happened to her, she would've never been in the prime position to be put up for that talk show. LB: Oprah told us, The setback is a setup. It's so tidy, but it's absolutely true: That thing that knocks you down can spring you back.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

The Year of "Mar-a-Lago Face"

It’s time to talk about the campy aesthetic of Trumpworld women.

By Nona Willis Aronowitz

What, exactly, is the “MAGA look”? Like pornography, you know it when you see it: It’s an exaggerated performance of traditional gender norms so common among the women of Trumpworld that it’s known as “Mar-a-Lago face.” It may involve Botox, cheek implants, fake eyelashes, injected lips, glossy waves, and a surfeit of bronzer. Think of the over-the-top looks sported by DHS Secretary Kristi Noem, strategist Kimberly Guilfoyle, and former RNC chair Lara Trump (as well as a few rightwing men, like Florida congressman Matt Gaetz).

What does this increasingly ubiquitous look tell the world about gender and power? What do these women gain from transforming themselves? And is it even worth talking about, given the recent onslaught of horrors? I called writer Inae Oh–who consulted historians, sociologists, and plastic surgeons for the best piece I’ve read on the subject, a Mother Jones feature–to ask about the deeper meaning of the trend.

Nona Willis Aronowitz: Before we get into it, what would you say to those who think focusing on people's (and mostly women's) looks is besides the point—that we should solely focus on their terrible actions? Are we just using the same weapons against them that people have always used against women?

Inae Oh: I would say, “I hear you!” But I would also argue that it is a mistake to dismiss the issue as superficial–the aesthetics of fascism have long been preoccupied with restoring gender norms and ideas of perceived "perfection," something we clearly see playing out both in the aesthetics and politics of MAGA.

Believing that this is besides the point also risks misunderstanding the forces that animate Donald Trump: appearance over substance, one's TV performance over policy, propaganda vs. reality. These are some of the most powerful people in the United States, imposing some of the most consequential policies in decades. Their deliberate choices are worthy of interrogation.

Kristi Noem has been such a central figure in the last couple of months. What does her visual presence signal to you?

Her aesthetic choices dovetail very nicely with the administration’s promise to take mass deportations to an unprecedented level. This is a priority for them, and the face of that priority really matters to Trump. I think there’s a reason why it’s not Stephen Miller out there. Trump has explicitly stated to Noem, “I want your face in the ads.” She’s gone through a dramatic transformation from when she was South Dakota's governor to what she looks like now.

Basically, she’s a woman with a look that’s very rooted in conservative, traditional ideas of what a woman should look like: long, flowing hair, heavy makeup, form-fitting dresses–but at the same time she has that baseball cap on and she’s employing incredibly harsh and cruel and aggressive policy. That supposed contradiction is intentional. Her look also provides cover for the brutal policies that are being implemented across the country. [After Sen. Alex Padilla was forcibly removed from a press conference], Rep. Anna Paulina Luna (R-Fla.) defended Noem and described her as “the most delicate, beautiful, tiny woman.” She said, “What actual testosterone dude goes in and tries to break Kristi Noem?” All of a sudden, she’s a defenseless woman.

There are certainly some precedents to the MAGA look in conservative politics and media; Fox News hosts of the last couple of decades come to mind. What’s different now?

I mean, it’s Donald Trump. It’s turbo-charged now. This is a man who literally has a background in reality TV. This is a man who doesn’t really know policy, who only cares about how you appear and how you can sell a certain idea. And [Trump’s taste is] extremely garish. Trump is notorious for his love of gold. It can seem so tacky to me, personally, but to him, it signifies wealth and power. When you have the most powerful man in the world having those priorities, people use these visual signifiers to gain power and favor.

Is this really just a rightwing thing? Lots of people, particularly women, feel pressure to conform to a certain look, which increasingly includes cosmetic enhancements.

I’m also a woman in this world, and I absolutely partake in our capitalist beauty standards. Plenty of people on the left, people who are my friends, are also opting to undergo procedures like Botox. You have Gen Z on TikTok being very open about the work they’ve done on their faces. For the longest time, plastic surgery was not accessible to the masses…As it has gotten cheaper and more normalized, people have become more open about it, like how Kris Jenner documented her facelift.

So it’s not completely divided by politics, but I think what’s happening on the right is a bit different. It’s such an appeal to tradition, whereas on the left, there’s more of an embrace, politically and culturally, of gender fluidity. And there’s more of an embrace of sustainability with companies like Reformation and green-friendly makeup, whereas on the right, that’s not at all a concern; it’s all about excess.

Men are secondary to this phenomenon, but they’re certainly in the mix. How do you think the MAGA aesthetic plays out when it comes to masculinity?

Pete Hegseth, to me, is the male equivalent of Kristi Noem. Men like him wear these bright-colored blue suits that don’t just fade into the background, and are supposed to be a sign of patriotism. Their shoulders are extremely broad, whether that is natural or not. Their chins, their jaws are very chiseled. It’s such an aggressive, cartoonish way to represent gender norms, and that absolutely plays into this Donald Trumpian idea of a powerful man. It’s not as ridiculous as the women, maybe because they don’t wear as much makeup. Do these rightwing men want to be known for caring about their looks? Absolutely not. They would see that as a sign of weakness. But there have been reports of Hegseth installing a makeup room in the Pentagon. [“Totally fake story,” Hegseth responded on X.] He puts that same importance on visuals and the message, rather than budgets and policies.

The Evolution of the Rightwing Lewk

Conservative politics has always demanded that women perfectly embody the gender norms of the era.

1970s: Phyllis Schlafly

The “godmother of the conservative movement” intentionally wore ultra-feminine outfits–preppy pastels, skirts in the pantsuit era, and pussy bows–while attacking the Equal Rights Amendment.

Early ‘00s: Gretchen Carlson

Famously crowned Miss America in 1989, she was one of many prominent “Fox blondes.” (In a twist, she was later key to taking down Fox News CEO Roger Ailes for sexual harassment.)

2008: Sarah Palin

Known for her sexy soccer mom look (with a rifle!), she ushered in a departure from the gender-neutral appearance of most female politicians at the time.

2025: Kristi Noem

Tasked with carrying out some of Trump’s cruelest policies, she is the platonic ideal of Mar-a-Lago face: pillowy lips, blinding white teeth, long wavy hair, and lots of makeup.

The Wonder of Amy Sherald

Ordinary Black life is extraordinary in the artist’s first major mid-career museum survey.

By Rebecca Carroll

Last month, The New Yorker featured a breathtaking portrait on its cover by celebrated Black American artist Amy Sherald. First painted in 2014 and titled “Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance),” the portrait of a young Black woman wearing a bright red hat is the same piece Sherald later submitted in a competition at the National Portrait Gallery. She won the competition, which caught the attention of former First Lady Michelle Obama, who then personally chose Sherald to paint her portrait for the National Portrait Gallery—making the Georgia native the first Black woman artist to be selected for an official presidential portrait. The Obama painting changed the entire trajectory of Sherald’s career, and since then her figurative grayscale portraits have been shown in public and private collections around the world.

Now, Sherald is having her first major museum survey at The Whitney Museum of American Art, called American Sublime, a title borrowed from the poet Elizabeth Alexander’s book of the same name. I’ve known and admired Sherald for years, and I was thrilled to sit down with her to talk about her work in this truly transcendent exhibition.

Rebecca Carroll: The last time we saw each other in person was pre-Michelle Obama portrait, when we randomly ran into each other on the street in Brooklyn. And here we are today to discuss your first solo exhibition at The Whitney. How are you feeling?

Amy Sherald: I told a friend last week, “I don’t know, I just feel emotional.” And she’s like, “Well, you’re getting used to belonging to the world, and not just to yourself.” Hearing that made me want to cry, and I left her a voice text, and said, “Okay, I’m sitting here holding back tears because I am a thug and I do not like to cry. But that’s exactly what I feel like.”

It’s a lot! The show is also set against a backdrop of political turmoil in America, particularly in regards to race, and actually not dissimilar to what we were experiencing when we last saw each other. At that time, the height of Black Lives Matter, I had written a piece for the LA Times, saying “Even as we see images of what most of us already know, that police violence against Black people in America is occurring with vicious regularity, something remarkable is materializing in its wake. We are also bearing witness to a pronounced moment of Black cultural ascension.” How has your work been impacted by eras of Black cultural ascension versus centuries of Black oppression?

My work was essentially born out of the desire to free myself from a history of oppression, but also in celebration of these eras of enlightenment. What I want the viewer to experience, and I say this in the exhibition [statement], is “the wonder of what it is to be a Black person.” I’m no longer religious, but I speak about this in that language of flesh and spirit—because part of us always has to be activated [in fighting oppression].

Right, exactly. I know you consider yourself as much a storyteller as an artist. As Black storytellers, I feel like we never make anything without parts of each other within us—intergenerationally, ancestrally, futuristically. But when the work goes out into the world and starts to belong to non-Black people, I sometimes feel these waves of protectiveness about it. Do you ever feel that way about your work?

I want the work to belong in the world because it was the only way that I could figure out how to counter whiteness, and the way that everything is saturated with it, comes from it, and evolves around it. My response to that is to make something that’s just as universal, and that can be consumed in the same way, because then [white people] are going to be consuming it in the same way that I had to consume Barbie, and all of these other things.

A pointed example for me was when your portrait of Breonna Taylor was on the cover of Vanity Fair, and it felt so unjust to me that suddenly white people were allowed to look at her in this way that we had seen her all along. Did you feel any conflict about that specific piece?

I didn’t, because of how it started. It started with Ta-Nehisi [Coates], and I trusted him and his vision. Maybe if the call had come from somebody else, then yes, but because it was Ta-Nehisi, no.

To clarify for our readers, Coates was the guest editor for that particular issue of Vanity Fair, and so that makes a difference, for sure. Now that the portrait is part of this exhibition at The Whitney, what has been the broader response to it?

A lot of people, of all races, are moved to tears by it. After I first finished it, I was really just thinking about how I’ve made this portrait, we’ve photographed it, it’s been on the cover of Vanity Fair, and now it’s in my studio. Now what can it do? I started some conversations, and it ended up being acquired by the National Museum of African American History and Culture. And now there’s a Breonna Taylor Legacy Fellowship and Breonna Taylor Legacy Scholarships for undergraduate students and law school students [at the University of Louisville, in Louisville, Kentucky, where Taylor lived; the fellowships are funded by proceeds from the portrait’s sale]. So if a student is doing anything in regards to social justice, whether their major is political science or art, they have an opportunity to get this scholarship. And then if a student is in law school and wants to work expungement [when a criminal record is erased or made unavailable for public access] cases in Alabama, which pays nothing, then here’s $12,000 to get you through your summer.

Does the idea that Black artists do work for each other resonate with you?

I feel like we make what we make because we are who we are. My mom told me this story about myself, and it stuck with me because I think my work sits in the world in the same way. [When I was a child] sometimes when we had dinner, I would just randomly get up and walk around the table and touch everybody on their shoulder and say, “I love you.” I would go all the way around, and then come sit down and finish my dinner. I think these portraits are “I love yous” out in the world to affirm anybody who is willing to see past the exterior and go deeper into their experience of what it means to be a human.

I love that story. And what do you experience when you look at your work?

I feel like the work sits in The Whitney, and there are words on the wall that explain it, but that work is me—somebody who was once a people pleaser and had a problem saying no, someone who doesn't like conflict or confrontation. My personality made that work.

I would never have looked at your work and thought, “These pieces were made by someone who had a problem saying no.” Are there specific things in the pieces that signal that to you?

I guess that’s where the beauty comes from, because the work doesn’t yell at you. It speaks to you nicely. If you feel uncomfortable in the presence of a Black person, this work will make you think, “Okay, well, maybe I don’t need to grab my purse. I might feel safe in the elevator with this guy.” It speaks to people that way. I went to Catholic school from K through 12, and was always one of two or three Black kids, so I have a lot of patience. I learned a lot of, “Let me explain to you why you can't say that.” Versus my friends that went to all-Black high schools, where it’s just like [gestures taking her earrings off], “Let me tell you…”

But you feel differently now, right? You’re in a different place. How do you think that will affect your work moving forward?

I’m not sure how the work is going to evolve to match who I am now, which is somebody who’s stronger, who doesn't mind saying no, and will look at you while you feel uncomfortable with my answer. I am excited because everything that I’ve made in this show has been living in my head for 20 years.

Does it feel like a kind of excavation in that way?

It feels more like a birth than an excavation. When I think about Black American art history and just our legacy within the larger canon, I feel like we don’t or can’t function on the same timeline as everybody else. It still feels like the beginning of something, this moment of myself, Rashid Johnson, Lorna Simpson, and Jack Whitten [all currently having museum shows]. It feels really great despite everything that’s happening. The art world is representing the world that we want to be—the real world right now.

What happens next for you?

I’m hoping that this show will make it into the National Portrait Gallery without having to make any compromises based on who’s sitting in an office at the White House. And I don’t mean, “Well, if I can’t have this painting of two men kissing and a trans person, then I’m not going to do the show.” I feel like that would be a mistake. I feel like it’s a mistake to step down from boards just because [Trump] wants to take over the Kennedy Center. Now more than ever, I feel like it’s important we be in those rooms and not shutting down the conversation. I think the bigger moment would be the work being in the Smithsonian Institution and people coming there to look at American history and Presidents, and then walking into my exhibition.

Whatever the fate of the work in this show, one of the things that really came through as I was walking through the exhibit, just like the way you used to walk around your family’s dinner table and tell everybody you love them—all of these people are taking care of each other, and I felt tapped on the shoulder and loved by every one of them.

Exactly as you should have felt.