The Formula for Equal Parenting

February 3, 2026 Greetings, Meteor readers, I made croissants this weekend. From scratch. I’m not saying that I’m better than y’all now, but I am typing this with my nose up a little higher than usual.  In today’s newsletter, Nona Willis Aronowitz upsets all the granola moms. But before that, we take a look at the DOJ’s latest blunder. Butter fingers, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON“Indefensible”: Like manna from the depths of hell, another bundle of Epstein files was released to the public last Friday, six weeks later than promised. The drop included millions of documents and redactions to the nth degree, but as we quickly learned, not everyone got the same level of black-box protection. The New York Times first reported that the DOJ published several images of naked women, some of whom may have been teenagers, while covering the faces of Donald Trump and other unnamed men who are seen in photos with well-known figures (Steve Tisch, Elon Musk, and Casey Wasserman, to name a few). As ABC News reported over the weekend, names of and identifying information about victims that had not previously been made public were also exposed in this drop. The images were later corrected after the Times alerted the DOJ to the errors. But, for those whose names and identifying information were left unredacted for hours on Friday, the damage had already been done. Lawyers representing over 200 accusers requested that the documents be taken down altogether so the DOJ could redact the documents properly. Another group of survivors released a statement, which reads in part, “This is a betrayal of the very people this process is supposed to serve. The scale of this failure is staggering and indefensible.” It couldn’t be any clearer who the DOJ truly wants to protect, which is probably why survivors are calling on Attorney General Pam Bondi to answer for these failures when she appears before the House Judiciary Committee on February 11. What happens now? According to Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche, “There’s a lot of horrible photographs that appear to be taken by Mr. Epstein or people around him,” he said, “but that doesn’t allow us necessarily to prosecute somebody.” He also added that with the release, everyone could check the documents themselves and “see if we got it right.” My law degree from the academy of Dick Wolf Productions doesn’t exactly qualify me to double-check the work of the Department of Justice, but it’s safe to say that telling victims to DIY their own cases against the richest and most powerful men in the country is a non-starter. Meanwhile, Bill (who appears in several photos in the latest files) and Hillary Clinton have agreed to testify before the House Oversight Committee. It will come as a surprise to absolutely no one if, after their testimony, the DOJ suddenly decides prosecuting Trump’s biggest enemy is a top priority. AND:

A Feminist Love Letter to Baby FormulaIs it the key to a more equitable partnership? The Meteor’s Nona Willis Aronowitz makes the caseBY CINDI LEIVE  NONA'S PARTNER, DOM, AND THEIR TWO CHILDREN. (PHOTO COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR) Two days ago, in The New York Times, my colleague Nona tossed a lovingly crafted, deeply researched grenade into one of the more passionately held beliefs about parenting: that breast is best. The title of her piece, “The Secret to Marriage Equality is Formula,” argues exactly that, but it goes further—Nona argues that formula (often a source of raised eyebrows in feminist circles for some very good reasons) can also be the secret to less stress and happier parenting for women in or out of partnerships. The piece struck such a nerve that the comment section is now closed. But after breast-feeding two babies myself, and feeling guilty whenever I used formula, I had questions. First off, for those who didn't read the piece, how did you personally discover that the secret to marriage equality is baby formula? I discovered this the hard way. The first time around, with my daughter Dorie, I breastfed because it seemed like the default: Everybody assumes that if you can breastfeed, you should breastfeed. While breastfeeding was a very nice way to bond, the experience was also very intense: It led me to desperately want to control the feeding realm. I was learning so much about her, which led me to push my partner, Dom, out of the space (he didn’t exactly argue—socialization runs deep!). Meanwhile, I was sleep-deprived, isolated, and resentful. I felt like I hadn’t signed up for being Mom-In-Chief with a hapless underling as a co-parent. My husband and I fought constantly, which wasn’t good for any of us, including the baby. So, when we had a second daughter, Pearl, we figured we should try to prioritize equality, even if it undermined breastfeeding. It seemed like a small price to pay for a harmonious experience, and for my baby to genuinely have a wonderful bond with her father from the get-go. And you know what? It worked almost instantly. I breastfed exclusively for two weeks just to establish breastfeeding, and it was like PTSD—all of the bad feelings came flooding back. But as soon as we started introducing formula and Dom started doing overnight feeds, the vibe in our household totally changed.I felt so much closer to him, I felt so much happier to see my baby in the morning, and he really learned Pearl in a way that he didn't learn Dorie until she was a toddler. As we used more formula and bottles, he was just as good at soothing the baby as me. The comments on your piece are copious and mostly very positive, from women saying thank you, we should have options. There were two other strains of responses I wanted to ask you about. First, from people who say: Just pump! And second, from people noting that the scientific evidence shows that breastfeeding is medically superior. Let’s start with the idea that pumping breast milk could solve the equal parenting issue.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

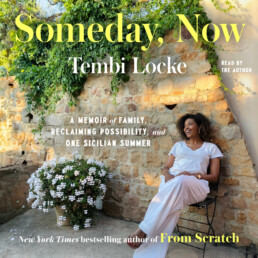

It’s Time to Rethink the “Empty Nest”

Author Tembi Locke talks about the grief, joy, and evolution of sending a child out into the world

By Rebecca Carroll

When I was a budding young feminist growing up in the 80s, I would occasionally hear adults use the term “empty-nest syndrome” to describe the experience parents go through when their children leave home for college. The narrative around it was always very gendered, and usually homed in on the loss of identity for the mother: Who even was she without her children at home? I remember thinking, both judgmentally and naively, “Oh my god! Your children are not your identity! Women are more than just mothers!” I also thought it was a classist assumption that all kids go to college, but whatever.

Decades later, as I find myself going through this experience myself (my son just started his third year of college), I’ve come to realize that “empty-nest syndrome” is not about whether or not your kids are your identity, but rather, the complex shift in dynamic that happens when your children leave home, and the overwhelming sense of grief that can come along with it.

Lucky for me, and all of us, bestselling author Tembi Locke has a new audiobook memoir, Someday, Now, that is about precisely this. Locke’s first memoir, From Scratch, which was adapted into a Netflix miniseries starring Zoe Saldaña, followed her experience as a young woman studying abroad in Florence, where she falls in love with an Italian chef, marrying him, and then losing him to a rare form of cancer when their adopted daughter Zoela is just seven. Someday, Now picks up after more than a decade of Locke single-parenting Zoela, and it’s the summer before she’s about to leave for college. The two take a trip back to Italy together to prepare, reimagine, and find joy in the culture and comfort of extended family in another country. I was delighted to sit down with Locke to talk about this period of life that is often so swiftly dismissed, especially for women.

Rebecca Carroll: What are your feelings about the actual term “empty nest”?

Tembi Locke: I rebuke the word “empty” because nothing about my life is empty. Not my spirit, not my relationship with my child. And I’m not going to characterize my life with an adjective that starts with “empty.” I choose instead to take this time to think about what is full in my life, and what I would like to invite back into my life. I didn’t rush into a bunch of hobbies. I didn’t rush into a Zumba class. I just needed to hang out in the question and see what would emerge.

What do you think people get wrong about navigating this time in our lives as parents?

That there is a-one-solution-fits-all. Like, “Okay, I’ll cry. I’ll have my feelings the first month or so. And then I guess it just all kind of resolves itself in some way.” There’s this sense of not slowing down to acknowledge the depth, the tectonic shifts that are happening. I had a work colleague who said something along the lines of, “Oh, well, now you'll just have more free time, you can do more work!” And I was like, “I am so sorry. I lean way the hell out of that thought.” I actually need to slow down and really take inventory before I proceed.

I was so struck by the way you connected your grief about Zoela leaving with your grief over losing your husband. When my son left for college, it almost felt like a sick joke: Having this child of my body was such a balm, and then 18 years later, he leaves? I was not prepared for the sudden grief. Why don’t we ever talk about that emotion?

We’ve mostly lacked the language and rituals to process in those terms. Our children go off, and then it’s suddenly like, “Wait, what the hell just happened?” Because I have had the direct experience of grief before, I was like, “This feels eerily similar in my body.” So in a way that made me perhaps more acutely attuned to name it.

You talk in the book about making certain choices around what feelings to share with your daughter and which to save for your therapist…

What’s funny is, the first summer she came back, that’s when I realized, “Oh, it’s not just about us being apart and then coming back together.” That’s when the actual renegotiation of the relationship really began, because I understood that the child who left is gone now. I remember saying to her, “I’m not a roommate, I’m actually the person who will be up at night thinking about your safety at a certain hour.” I was trying to keep the long vision in mind, because for 18 years, my job was to rush in to some degree, fix things. But that’s not the role now. I also realized that feelings I experienced as my younger self were activated by my child leaving—and that is the work of a therapist to unravel.

My son and I were very close when he was younger, in part, I’m sure, because he knows that I am adopted, and he understood how important his biological connection is to me. Now there’s this letting go that feels like abandonment. I can’t not express sorrow…and yet, I don’t want to make him feel bad.

I try to pre-process some things for myself before I open my mouth. I was experiencing it, as I say in the book, with a tinge of maybe even shame. Like, how can I use the word “abandonment”? How is a child abandoning a parent?

To the idea of pre-processing—the summer before my son went off to college, I had two TV writing projects in the pipeline, which I had planned would keep me very happily distracted. Then the writer’s strike happened, and suddenly, I had a lot of time on my hands. I would have missed him anyway, of course, but without work to busy myself, I was almost paralyzed by his absence. It was bad. I couldn’t even look at his favorite foods in the grocery store. How do we reconcile these feelings without also experiencing, as you said, some measure of shame?

One of the things that I needed to do as a mother after Zoela left home was to actively bookend every difficult, challenging, or fearful thought with an acknowledgement of the hard work, the joy, and the sense of security that we had co-created together. I even did a ritual for myself to acknowledge those 18 years, because as a solo mom and a widowed parent, there were a lot of challenges.

What was the ritual?

I did 40 days of journaling where I just set aside time each day, lit a candle, and I just wrote to the idea of…motherhood. I carved out space to allow whatever would come up around the topic of this beautiful life experience I had that wasn't done yet. It was shifting, but it’s not done. Motherhood doesn’t end. But it is changing.

Three Questions About...Baby Sleep

We spoke with Dr. Harvey Karp, inventor of the SNOO, about soothing the ills of modern parenthood.

By Nona Willis Aronowitz

Whether or not you know Dr. Harvey Karp by name, you’ve probably absorbed his influence on baby sleep and soothing. The resurgence of the swaddle? The ubiquity of white noise in babies’ rooms? Cribbed (no pun intended) from Dr. Karp’s bestselling book The Happiest Baby on the Block. And he’s probably best known for SNOO, a pricey “smart bassinet” that rocks and jiggles a strapped-in baby all night long. In my ninth month of pregnancy, I spoke with Dr. Karp about the evolution of his signature product, what nuclear families are missing, and why sleep is a feminist issue.

When SNOO first came out in 2016, it was a signifier of luxury–Beyoncé and Jay Z reportedly owned several. Now, it’s used in hospitals, including to soothe babies who were born dependent on opiates, and you’re working to have SNOO covered by Medicaid. That seems like quite a shift–how did that come about?

Yes, SNOO was really known as this bougie baby bed in the beginning, but the goal was always to make it accessible to everyone. We built the bed to be reused over and over again. It’s sort of the way breast pumps started out: There were these industrial breast pumps and they were too expensive for people to buy, but you could rent them. And so, our goal was always to have SNOO be either rented or for free, and not to be purchased and owned.

We have a project going on in Wisconsin right now, where hundreds of [SNOOs] are being given to families who have premature infants, mostly Medicaid recipients. Our job is to develop the science to convince Medicaid payers that we can save money and improve outcomes. We’ve also had a lot of success with companies offering SNOO as an employee benefit. Now, tens of thousands of people get a free SNOO rental from their employer, from big companies like Dunkin' Donuts to the largest duck farm in America.

You often say that SNOO can help replenish what we’ve lost in terms of the extended family and support for new parents. But I think some people still feel a little funny about swapping out human cuddles for a machine. What do you say to that?

Yes, a hundred years ago, and for the entire history of humanity, we had extended families, and people lived right next door to their grandmother, their aunt, their sister, and everybody shared the work. Then we moved to the city or moved hours away from our family, and women got more work responsibilities outside the home. This became pretty crushing on parents, especially single parents. So the SNOO goal is to be a helper. It's there in the home when you're cooking dinner, when you’re taking a shower, when you're playing with your three-year-old, when you are getting some sleep. It’s not set it and forget it, but it can give you 20 to 30 minutes here and there, as well as giving an extra hour or even up to two hours of extra sleep.

In the womb, the baby is being held 24/7. Then they’re born, and 12 hours a day we put them in a dark quiet room. That’s sensory deprivation compared to what they had before they were born. So why, because you only have a few people in your family, should the baby miss out? SNOO…doesn’t replace what the parents would be doing, because no one can rock them all night long. It just gives the baby a little extra.

When I had my first baby, sleep was a locus of inequality in my relationship–my male partner was obviously getting more of it, especially because I was riddled with anxiety about whether my baby was safe. Sleep became a feminist issue in my mind. How do you see SNOO responding to these gender dynamics, which seem to be common?

We’ve definitely moved in the direction of gender equality, but we’re still far from it. Even when the baby is sleeping, sometimes moms are awake and anxious knowing that they have to get up in three hours. SNOO can help with that: There have been studies reporting that SNOO reduces maternal depression and maternal stress. There are five things that trigger depression and anxiety that SNOO improves: up to 41 minutes more sleep for mothers per night, reduced infant crying, less anxiety that the baby is in danger, the feeling that you have a support system, and [the fact that it] makes you feel like you’ve gotten things managed better. Also, men very often take on the role of being the sleep experts when they have a SNOO in the house. Men want to manage this gadget. That takes a burden off the shoulders of the mom.

This conversation was made possible by Happiest Baby, a sponsor of UNDISTRACTED with Brittany Packnett Cunningham.

Postpartum Depression is a "Gift"

July 24, 2025 Howdy, Meteor readers, I spent half my day in the waiting room of an auto shop watching reruns of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit. The things Olivia Benson has been through are insane; no wonder this show is such effective copaganda.  In today’s newsletter, we’ve got babies on the brain. Nona Willis Aronowitz, whose own baby is due any day now, explains the latest MAHA tomfoolery on postpartum depression and then asks three very important questions about baby sleep. Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONMAHA targets mamas: Earlier this week, an FDA panel discussing the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) during pregnancy made waves in the medical community–and not the good kind. It was so chock-full of misinformation and “MAHA talking points” that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) felt compelled to put out a statement calling the panel “alarmingly unbalanced” and accusing it of ignoring “the harms of untreated perinatal [before, during, and after birth] mood disorders in pregnancy.” A quick review of the accepted scientific facts here: Postpartum depression affects one in eight women; mental health conditions, including suicides and overdoses, are a leading cause of death in pregnant women; and maternal mental health has taken a nosedive in the last few years. Meanwhile, there’s medical consensus that the small risks of taking SSRIs during pregnancy are far outweighed by the serious risks of untreated depression. Yet the vast majority of panel participants repeated widely debunked lies about the dangers of taking SSRIs while pregnant, claiming that the medications pose an increased risk of autism (they don’t), as well as preterm birth, pre-eclampsia, and postpartum hemorrhage (the effects are negligible). Even more enragingly, as Mother Jones’ Julianne McShane pointed out, several of these “experts” seemed to deny the gravity and even existence of the reason many patients might choose antidepressants to begin with: perinatal depression itself. Dr. Roger McFillin, a psychologist and anti-vaccine advocate, suggested that women are “naturally experiencing their emotions more intensely, and those are gifts,” not “symptoms of a disease.” FDA Chief Dr. Martin Makary opted to discuss the “root causes” of perinatal depression, like the lack of “healthy relationships” and “natural light exposure,” rather than the immediate solutions patients need. And a third male panelist, Dr. Josef Witt-Doerring, who runs a clinic that helps people wean off psychiatric medications, claimed that symptoms of depression “are not things to be fixed with medical intervention.” As a very pregnant person who’s intimately aware of the havoc hormones can wreak, these words make my blood boil–no, incinerate. With my first child, I had clinical anxiety, both during and after my pregnancy. It cost me a lot: sleep, relaxation, closeness with my partner, peace with my baby. I’m a white, educated woman who’s squarely in the demographic of people who take SSRIs most frequently, yet the stigma was still too strong for me to seriously consider the drugs. I gutted it out for far too long, and it was tough to claw my way back. But halfway through this pregnancy, as the memory of those dark times loomed, I gingerly asked my midwife whether she thought a low dose of SSRIs would prevent a disastrous redo. It was only after she reassured me it was safe and effective, sending me links to several studies, that I started taking a prophylactic dose of Zoloft in preparation for birth. Among the FDA panel’s proposed solutions was to slap a black-box warning about the use of SSRIs during pregnancy. This kind of warning might very well have deterred me–someone with a lot of access to information. I can only imagine how many more suffering women it could discourage. Like many issues the MAHA movement focuses on, this one dovetails with legitimate concerns about the overprescribing of SSRIs and the lack of holistic support for people struggling with their mental health. Those are real problems. But steering new moms away from evidence-based help can only lead to harm. “So many women I see feel guilty about taking medications,” Dr. Nancy Byatt, a perinatal psychiatrist at the UMass Chan Medical School, told The New York Times after she watched the FDA panel. “They think they should ignore their needs for their babies. And I think it could make their decisions a lot harder … because it could cause unnecessary alarm.” The Department of Health and Human Services has refused to comment on future policy decisions, but in the meantime, you can still get accurate pregnancy information from ACOG and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. —Nona Willis Aronowitz AND:

WHAT ALL THE AI CHATBOTS ARE GOING TO START SOUNDING LIKE ONCE THEY BECOME UNWOKED.

THE UNINSURED ICON. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)

Three Questions About...Baby SleepWe spoke with Dr. Harvey Karp, inventor of the SNOO, about soothing the ills of modern parenthood.BY NONA WILLIS ARONOWITZ  DR. KARP, BABY WHISPERER. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Whether or not you know Dr. Harvey Karp by name, you’ve probably absorbed his influence on baby sleep and soothing. The resurgence of the swaddle? The ubiquity of white noise in babies’ rooms? Cribbed (no pun intended) from Dr. Karp’s bestselling book The Happiest Baby on the Block. And he’s probably best known for SNOO, a pricey “smart bassinet” that rocks and jiggles a strapped-in baby all night long. In my ninth month of pregnancy, I spoke with Dr. Karp about the evolution of his signature product, what nuclear families are missing, and why sleep is a feminist issue. When SNOO first came out in 2016, it was a signifier of luxury–Beyoncé and Jay Z reportedly owned several. Now, it’s used in hospitals, including to soothe babies who were born dependent on opiates, and you’re working to have SNOO covered by Medicaid. That seems like quite a shift–how did that come about? Yes, SNOO was really known as this bougie baby bed in the beginning, but the goal was always to make it accessible to everyone. We built the bed to be reused over and over again. It’s sort of the way breast pumps started out: There were these industrial breast pumps and they were too expensive for people to buy, but you could rent them. And so, our goal was always to have SNOO be either rented or for free, and not to be purchased and owned. We have a project going on in Wisconsin right now, where hundreds of [SNOOs] are being given to families who have premature infants, mostly Medicaid recipients. Our job is to develop the science to convince Medicaid payers that we can save money and improve outcomes. We’ve also had a lot of success with companies offering SNOO as an employee benefit. Now, tens of thousands of people get a free SNOO rental from their employer, from big companies like Dunkin' Donuts to the largest duck farm in America. You often say that SNOO can help replenish what we’ve lost in terms of the extended family and support for new parents. But I think some people still feel a little funny about swapping out human cuddles for a machine. What do you say to that? Yes, a hundred years ago, and for the entire history of humanity, we had extended families, and people lived right next door to their grandmother, their aunt, their sister, and everybody shared the work. Then we moved to the city or moved hours away from our family, and women got more work responsibilities outside the home. This became pretty crushing on parents, especially single parents. So the SNOO goal is to be a helper. It's there in the home when you're cooking dinner, when you’re taking a shower, when you're playing with your three-year-old, when you are getting some sleep. It’s not set it and forget it, but it can give you 20 to 30 minutes here and there, as well as giving an extra hour or even up to two hours of extra sleep. In the womb, the baby is being held 24/7. Then they’re born, and 12 hours a day we put them in a dark quiet room. That’s sensory deprivation compared to what they had before they were born. So why, because you only have a few people in your family, should the baby miss out? SNOO…doesn’t replace what the parents would be doing, because no one can rock them all night long. It just gives the baby a little extra. When I had my first baby, sleep was a locus of inequality in my relationship–my male partner was obviously getting more of it, especially because I was riddled with anxiety about whether my baby was safe. Sleep became a feminist issue in my mind. How do you see SNOO responding to these gender dynamics, which seem to be common? We’ve definitely moved in the direction of gender equality, but we’re still far from it. Even when the baby is sleeping, sometimes moms are awake and anxious knowing that they have to get up in three hours. SNOO can help with that: There have been studies reporting that SNOO reduces maternal depression and maternal stress. There are five things that trigger depression and anxiety that SNOO improves: up to 41 minutes more sleep for mothers per night, reduced infant crying, less anxiety that the baby is in danger, the feeling that you have a support system, and [the fact that it] makes you feel like you’ve gotten things managed better. Also, men very often take on the role of being the sleep experts when they have a SNOO in the house. Men want to manage this gadget. That takes a burden off the shoulders of the mom. This conversation was made possible by Happiest Baby, a sponsor of UNDISTRACTED with Brittany Packnett Cunningham.  WEEKEND READING 📚On the boys: Everyone’s worried about young men, but are we maybe blowing the “boy crisis” out of proportion? (The New York Times) On boobs: We’re all thinking about them. And apparently so is American Eagle. (TCF Emails) On the genius invested in women’s sports: The WNBA is in the midst of negotiations for a better bargaining agreement. They’ve got a Nobel Laureate in Economic Sciences on their side. (Sports Illustrated)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

American Moms Are Not Okay

May 29, 2025 Bonjour, Meteor readers, The French Open is well underway, and my Belarusian princess Aryna Sabalenka is still going strong, as is the people’s champion, Coco Gauff. Gauff’s match is playing in the background as I type, and just watching how she moves across the clay is shredding my old-lady ACLs.  WOW LOOK AT THOSE KNEES. I BET THEY DON'T CRACK JUST FROM TRYING TO WALK UP THE STAIRS. (VIA GETTY) In today’s newsletter, Nona Willis Aronowitz reveals the reasons behind a sharp decline in moms’ mental health. Plus, your weekend reading list. Serving from my seat, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONThe primal scream, now backed by data: If you have kids or spend time with people who do, you know that many moms are not okay. But a massive new study in the Journal of the American Medical Association puts data to vibes—and finds that mothers’ mental health is getting significantly worse. The study looks at self-reported survey results from nearly 200,000 parents from 2016 and then again in 2023. Over that time period, the percentage of mothers reporting that their mental health was “fair” or “poor” rose sharply, from one in 20 in 2016 to one in 12 by 2023. (Fathers did worse over time, too, but started in a far better place–in 2016, only one in 42 reported having “fair” or “poor” mental health, with one in 22 reporting the same in 2023.) As a pregnant mother of a young child, these results didn’t exactly shock me. In fact, the one-in-12-mothers-are-struggling felt low! Still, it’s worth asking why there’s been such a startling decline in only eight years (which started with Trump’s first term, jussayin’). Dr. Jamie Daw, assistant professor of health policy and management at Columbia Mailman School of Public Health and the lead author of the study, tells me there are myriad theories that have not yet been untangled–and that this trend pre-dates the parenting black-hole that was the pandemic. She points to economic factors like “inflation and income inequality” (while all socioeconomic groups experienced mental-health declines, single mothers and those with kids on Medicaid fared worst) but also moms’ “existential concerns like climate change, gun safety, and racism.” Dr. Daw also posits that the same “sense of isolation” that has become a national trend is hitting many mothers especially hard. More of them are feeling the impact of “weaker social support networks.” And yes, if you also clocked that 2016 lines up with a certain infamous election, that timing may be relevant: Dr. Daws says “it could be true that political polarization contributes to this reduced sense of community or even divisions among family members. There’s less social cohesion.” One more factor that could be driving these results? Less stigma around admitting that mothering is a Sisyphean task in America. Dr. Daw points out that these results are self-reported, meaning they’re “subjective and very influenced by norms and knowledge about mental health.” This, of course, doesn’t make them any less legit: “People’s own reflections on their mental health matter,” Dr. Daw says. “We want people to have the feeling that they’re thriving.” In any case, the study demonstrates the urgent need for what it calls “evidence-based policy interventions” for mothers (along with, I would add, non-policy interventions like more communal childrearing and dads getting off their asses). Things like free universal childcare, generous mandated maternity leave, and equal partnerships may not raise the birth rate, but they’d sure as hell make mothers’ lives better. —Nona Willis Aronowitz AND:

CHIURI TAKING ONE FINAL STRUT DOWN A DIOR RUNWAY. (VIA GETTY)  WEEKEND READING 📚On starting motherhood alone: Noor Abdalla, a dentist and first-time mom, has survived her first month as a single parent. Her husband, the detained student activist Mahmoud Khalil, has only been allowed to hold his son once. (The Cut) On following the money: Foundations are pulling funds from reproductive justice groups speaking out for Gaza. Renee Bracey Sherman explains the real cost. (Prism) On paid and unpaid care work: Tracy Clark-Flory spoke with artist Kim Ye on how her work as a Domme helped her create a more equitable domestic dynamic. (Tracy Clark-Flory’s Substack)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

"I woke up worried for my daughter."

November 6, 2024 Dear Meteor readers, You’re getting this email approximately 12 hours after Donald Trump secured his second presidential victory, and only minutes after Vice President Kamala Harris conceded in front of a tearful crowd at Howard University. Trump’s decisive win is still a fresh wound: We’re only in the earliest minutes of figuring out what it means for not just our democracy but our actual, real lives: how we work, where we are safe, who we need to hold close. As a media outlet, The Meteor tries to bring you reasonably thoughtful stories, analysis and videos. But as a group of real people negotiating emotions, The Meteor had a day like everyone else, and may or may not have typed this from a fetal position on the couch. Rage, disorientation, and heartache for the many people who put their lives on the line for change were all part of the mix. So while there’ll be plenty of time for action steps in the weeks (and, realistically, years) to come, today is personal. In this newsletter, six of my colleagues tell you exactly what today felt like to them. (We did have a no-false-hope rule: “You know we’re not gonna kumbaya our way out of this,” Shannon said at our editorial meeting this morning.) Here are their reflections. And we want to hear yours—find us at [email protected], or, as always, here. Grateful for all of you, Cindi Leive  “We have never been safe.”A Trump win hits different as a tranny. In 2016, I was a 22-year-old gay boy living in Houston, and I was scared. The day after he won, some men in a pickup truck drove by me and yelled, “TRUMP WON, FAGGOT!” And, obviously, that felt bad. But now…? I have an appointment to discuss getting back on estrogen (had to stop after a health scare) set for January 30—ten days after the inauguration. And no, I don’t think gender-affirming care will be outlawed in ten days. (Mind you, I also thought the sexual abuse court decision might make people give half a shit, so what do I know?) But it does have me acutely aware: How much longer do I have? That seems to be the common question for the trans people I’ve been talking to today: How much time do I have to change my name? How soon can I scrape the money together for surgery? How much longer can I stay in the state where I’ve built my home? If this truly is the fabric of the country we live in, will the remainder of my life be measured in decades, years, or weeks?  A national monument of enduring historical significance. And a fort in the background. (Photo courtesy of Bailey Wayne Hundl) I remember the first Trump presidency. I remember how new oppressions would burst from his administration like solar flares—fast, unpredictable, deadly—and burn whichever community happened to be standing in the danger zone. And if the focus of his most recent campaign is any tell, my community’s going to need some SPF 70,000. I feel my cis friends’ knowing gloom. I get texts telling me they’re so sorry. My boyfriend holds me as he describes what he’ll do if anything happens to me. The danger is real, and I’m not the only one who knows it. There are small bright spots, electorally speaking: Zooey Zephyr, an outspoken trans state senator in Montana, won her reelection with 83%. Sarah McBride (D-Del.) will be the first openly transgender congresswoman (although she does, I’m sorry to say, support Israel’s right to “defend itself”). And I am not so naive as to pretend that amassing electoral power is enough to save my community. But it is nice to know that the next time a legislator in a room full of people suggests “hey, let’s kill the transes,” someone will be in that room to say no. But oddly enough, what brings me the most comfort is the knowledge that this country has never had my community’s interests at heart. At best, we have had the illusion of safety with some semi-significant improvements to our material realities. But I’ve always been one pickup truck of men away from becoming a headline. And before I was born, my community had it even worse. And still we loved. And still we held each other close. And still we resisted, and made art, made protest signs, made love, cried, danced, survived another day. I’m reminded so often, but especially today, of these words from queer pastor Hannah Adair Bonner: “We have never been safe, but we have always been brave. We have never been given a space; we have always had to take it.” —Bailey Wayne Hundl, content editor  “I woke up worried for my daughter.”Here are two of the things I kept in mind when I voted last week: my abortions, and my daughter.  Nona and her daughter Dorie at the Jersey Shore. (Photo courtesy of Nona Willis Aronowitz) I’ve had two abortions—one at seven weeks because I didn’t want to have a baby, and one at 14 weeks because I very much wanted to have a baby but had gotten some horrible news from our genetic screening. Both took place in New York, where they were easy to schedule, covered by insurance, and within a few miles of my house. Both times, I envisioned myself living a parallel reality of a woman in an abortion-hostile state. In 2019, when I had my first abortion, I thought about the spate of “heartbeat bills” being proposed across the country, keenly aware that my procedure would have come too late if those bills had been law. In 2024, on the eve of my second, I thought about how my devastation would be compounded by planning an out-of-state abortion without medical guidance, amid work and childcare obligations and my own deep grief. Today, 17 states would have prevented me from having my first abortion, and 19 would have blocked the second. In each case, my life would have been irreparably changed against my will. Yesterday, I hoped that the country would elect a person who believes in every pregnant person’s right to shape their fate. That did not come to pass—even though voters approved seven more ballot initiatives codifying abortion rights, all meaningful victories that reflect abortion’s broad popularity. As I cuddled my oblivious, wriggling toddler this morning, I worried for her future. But I took a teensy bit of solace in her declaration of bodily autonomy as I tried to persuade her to go potty before we left for daycare: “NO, I don’t have to go pee!!!” she screamed. It was her body; I couldn’t make her do anything she didn’t want to do. My job will be to help her keep that sense of agency, that sense of self-ownership, for as long as humanly possible. —Nona Willis Aronowitz, contributing editor  “Sit in that discomfort.”I wish I could tell you that I was shocked by the news that Donald Trump will be the next president of the United States. But I don’t want to lie. I have seen the deep ugliness, the racism, the violence of this country. I have felt the fear of living as a visibly Muslim woman, the dread of being visibly queer, and even changed the way I speak so as to make myself non-threatening to white people. I have lived my entire life under the heavy thumb of a white-nationalist America that, until 2016, went largely unnoticed by those who benefited from it. But now you see it. You see him. You know now without any doubt what has always been waiting just beneath the surface for someone willing to say all of it out loud. Someone willing to say they will reshape this nation for the benefit of white, reactionary, Christian men. And perhaps seeing it in the harsh light of day grips you with fear. For some of us, these sensations are not new. But for many of you reading this, it’s the first time you’ve seen white supremacy so naked, so unabashed. And if you are in the latter group I challenge you to sit with that fact all day today. Sit in that discomfort. Don’t look for something to point to to make all of this somehow feel okay. Spend time in the knowledge that when given the opportunity to say “no” to a fascist, a majority of Americans chose to embrace him. I’ve lived under a blanket of white supremacy for 30 years. You can endure that feeling for 24 hours. And when we are ready to resume the fight—because we are going to fight—my guiding light will be the people of the Young Lords Party of the 1960s and ‘70s who, when everything was working against them, came together to care for their own. This group of young Latine and Black activists in New York and Chicago knew politicians would not save them and so they chose each other. They chose resistance. They chose to change lives. There is nothing stopping each and every single one of us from making that same choice. This is the moment. "El machete no es solo pa' cortar caña." —Shannon Melero, newsletter editor  “We are not the lost ones.” Rebecca and her sister in community building, Caryn Rivers. (Photo courtesy of Rebecca Carroll) For those of us who voted for decency: Decency lost, but we didn’t. We are not the lost ones. We are the ones who fought and will continue to fight for each other with our whole entire selves. As a Black woman in America who is resolutely clear about the work we do and have done for this country, I’m angry AF that a white man protected by the primal callousness of America won. But I am also buoyed by the brilliant fighters who, over the last century, turned community organizing into a collective blueprint for how to be in this world. Toni told us, Jimmie warned us, Octavia predicted this almost to the letter. Our work now is to evolve the language of telling, the tenor of warning, and the vision of predicting by tapping into the reserve of love and fight and compassion created by those of us who did vote for decency. We prioritized the future safety and wellness of each other over everything else. That priority hasn’t changed. —Rebecca Carroll, editor-at-large and founding collective member  “I didn’t realize how hopeful I was.”I know we’ll have endless discussions about what happened and who to blame—a lot of which will be misguided, some of it accurate but hard to hear. I see people on social media saying they knew this would happen. I respect that, but I’m shocked at how legitimately shocked I am. I didn’t realize how hopeful I was that people would not fall for Trump’s chaos again. And it’s hard for me right now to even begin to grapple with what’s to come. But as a writer and a movement journalist, I’m clinging to one thing I know to be true: There is no greater power than of the collective and of standing with each other, and there’s never been a moment in history when that part was easy or handed to us. I’m deeply grateful for every organizer today—every person who protested, door-knocked, talked to people, made art, bore witness to atrocity, and made impossible compromises. That said, I’m not creating today. Today, I’m listening and feeling, wrapping myself in a blanket even though it’s 75 degrees in November, and eating my favorite things while the wisdom comes and the ancestors show us the way. It’s coming. Some may say it’s already here. —Samhita Mukhopadhyay, former editorial director and collective member  “It’s going to be up to them.”Waiting for the girls to wake up was the hardest part. Hearing their footsteps on the stairs, eager for news. Knowing that I’ll have to find words, again, that instill hope and protect their young spirits, but also brace them for the realities of a country and a culture that thinks of them as less than the perfect, beautiful beings they are. Words they’ll remember and return to someday when they need to draw on reserves of strength to keep going in whatever fight they will inevitably be fighting. But this time they know more. They’ve seen more. As South Asian girls, they also see themselves in Kamala — and have now watched her come so close to realizing a dream that may not arrive anytime soon. In 2016, I wrote that I found my hope in their smiles, in the light in their eyes. Today there were no smiles. Today there were tears. The only thing I could do was to look at them and tell them that I still believe. That it’s going to be up to them. That they will be the ones to lead the next generation, with kindness, with integrity, and with love. And that I will be there for them, with them, always. I’ll be fighting too. —Tara Abrahams, head of impact  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Subscribe using their share code or sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()