The Call Is Coming From Inside the Villa

Love Island: USA has Latine viewers confronting their anti-Black history

By Julianne Escobedo Shepherd

Love Island is the escapist watch of the summer with its outsized personalities and tropical setting—but as the aftermath of this season has proven, it’s never truly an escape from the dynamics of the real world.

A little background if you’re not one of the tens (hundreds?) of millions that made this season Peacock’s biggest streaming series ever: Love Island is a reality show in which a dozen “sexy singles” are sequestered inside a neon villa with the sole directive to find love amongst themselves, has been airing for a decade in the UK, and six years in the U.S., but it didn’t really take off here until last year, thanks to improved production values after a switch from CBS to Peacock. This summer, it was an inescapable hit: Love Island seemed like the only thing unifying the country, to be honest, a fact I chalked up to our desperate collective need for an hour of reprieve from encroaching fascism. And since it airs almost every single day for two months, it’s easy to immerse oneself in the petty dramas and flirtations of its sculpted and spray-tanned twenty-something cast.

I’ve been watching Love Island for years—last summer I realized I had seen over 550 episodes, at which point I had to stop counting—and like the best reality shows, it manages to put larger-world concerns under a microscope; its anthropological utility is vast. Even in its unreal Fijian (or Mallorcan) setting, familiar biases and prejudices play out in real time. And this year especially, anti-Black racism has shown up both in the villa and among the show’s fanbase.

This year was notable for the way Olandria Carthen and Chelley Bissainthe, this season’s beloved Black women leads, were characterized by fans and certain tabloid media. They were both perfectly dignified and two of the main reasons the season was watchable—only to find that, having emerged from the villa at the end of the season, they’d been saddled with the “angry Black women” stereotype. (Production has also been accused of airing decontextualized outbursts by Huda Mustafa, Love Island’s first-ever Palestinian cast member and an outspoken mother, while editing out the male behavior that led to her outbursts.)

Further, two contestants, Yulissa Escobar and Cierra Ortega, were unceremoniously disappeared from the villa after old social media posts surfaced in which each used racist terms—the n-word and an anti-Asian slur, respectively. And last week, it emerged that previous contestants JaNa Craig and Kenny Rodriguez had broken up after a year—allegedly due to his racism against JaNa. (I’m using first names here since that’s the way viewers know the cast.) A post by friend and castmate Leah Kateb charged Kenny with being a “racist, clout/money hungry and a scammer,” while JaNa’s best friend, Charmane Smith, doubled down on the accusations, implying that Kenny had been texting friends about how he does not like Black women. Kenny has not yet responded to these specific allegations, but in aggregate, the headline-making racial dynamics that have surfaced are appalling.

And it was even more disconcerting that the three contestants accused of bias are all Latines of various origin, with a white Cuban from Miami (Yulissa), a Puerto Rican/Mexican Angeleno (Cierra), and a non-Black Dominican from Dallas (Kenny) at their center. As De Los’s Alex Zaragoza pointed out after Cierra’s ouster, “anti-Blackness and white supremacy is sadly part of the fabric of our culture across Latino communities in all parts of the U.S.”

Colorism and racism have long been a massive problem among our U.S. Latine communities, and in Latin America, too; it’s a pervasive issue that dates back to both the enslavement and genocide of Africans and the 15th-century Spanish invention of las Castas—the racial caste system put into place as the conquistadors colonized Indigenous lands. The idea that lighter-skinned people deserved higher social and economic standing was crucial for Spaniards in maintaining control, and it embedded itself into cultures across Latin America, with flare-ups along the way.

For instance, in the mid-century Dominican Republic, the dictator Rafael Trujillo used anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism to foment division and entrench his fascist rule (sound familiar?), a legacy that reverberates today. And for too long, mainstream media in Latin America has spread the message that white is more right, whether in the faces that populate our novelas or those that deliver our newscasts. (Recall, for instance, the racism faced by the Mixtec and Triqui actor Yalitza Aripicio, after her Oscar nomination for the 2019 film Roma.) In the U.S., white assimilation demands that Latines shed our identities, which is how you get brown Latines going full stan for Trump, even as his administration kidnaps and sends our families to concentration camps.

Fortunately, young people seem much more inclined to call out and combat anti-Black racism, and racism in general, among Latines. They know that Latines’ fraught experience with colonialism doesn’t excuse us from the task of trying to eradicate this problem within our communities and our families; that if we are to be united towards liberation, eliminating anti-Blackness from within is an essential first step. And if it takes Love Island, a reality show defined by thong bikinis and nasty-looking egg breakfasts, to spark this conversation, then I suppose we can call it a net good. Even if you inadvertently lose half your summer watching it.

Girl, What You Got in Them Jeans?

July 29, 2025 Hola, Meteor readers, I never truly mastered how to ride a bike. Attempts were made, but that whole idea of you never forget? You absolutely do. Normally, I don’t feel any kind of way about it, but after reading this piece in The Gist about the feminist roots of cycling and the Tour de France Femmes, I now have a strong feminine urge to hop on a bike.  THE ONLY KIND OF CYCLING I CAN MANAGE. In today’s newsletter, Rebecca Carroll joins us to talk about Sydney Sweeney and her jeans. Genes? Maybe both. Plus, a little happy dance to celebrate a Planned Parenthood legal victory. Pedaling to nowhere, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONThese jeans suck: Last weekend, the American Eagle clothing brand unveiled its new campaign, featuring “Euphoria” and “White Lotus” star Sydney Sweeney, with the tagline: “Sydney Sweeney Has Great Jeans.” The ads, which go predictably hard on the whole “sex sells” mantra of marketing, are every white guy’s wet dream. But it’s one specific video (which has since been removed) that was unmistakably provocative. And not in a good way. In this particular ad, the blond-haired, blue-eyed Sweeney is lying on her back, her jeans unzipped, when she starts to speak in her signature voice of affected listlessness: “Genes are passed down from parents to offspring, often determining traits like hair color, personality, and even eye color,” she says, as she slowly zips up and fastens the top button at her bare waist. “My jeans are blue.” And then the voiceover (male, of course) drives it home: “Sydney Sweeney has great jeans.” American Eagle has called the campaign “a return to essential denim dressing,” but critics have called it an idea that “shouldn’t have made it past the copywriter’s room” because of its clear nod to Trump’s view of “essentials,” and the white-supremacist pseudoscience of eugenics. And while “eugenics” may sound like an antiquated term, it’s very much still a part of our modern world. First developed in 1883 by British statistician and anthropologist Francis Galton, eugenics is the pseudoscience that argues selective reproduction between humans with “desirable traits” (read: white) can make for better and more desirable humans (also read: white) in society at large. If this sounds familiar, it should: Ideas like these have been a recurring foghorn during Trump’s rise. At one New Hampshire rally in December 2023, Trump told his audience, “We’ve got a lot of bad genes in our country right now,” and warned that undocumented immigrants were “poisoning the blood of our country.” During his first presidential term in 2020, he spoke to a rapt crowd of white Minnesotans and said, “You have good genes. A lot of it is about the genes, isn’t it, don’t you believe?” More than 30 years prior, in a 1988 interview with Oprah Winfrey, when asked about his path to success, Trump answered: “You have to be born lucky in the sense that you have the right genes.” And he’s created a cult-like following of white men in his administration who espouse these same beliefs. The “right genes” is the literal premise of the Sweeney campaign, and for American Eagle to push this kind of agenda, in this particular political moment—rife with tradwives, pronatalism, and exaggerated gender norms—feels like yet another corporate capitulation (hi, Paramount) to the dark, unapologetic depths of Trump’s hubristic agenda. (It speaks volumes about how compromised we’ve become that companies’ responses to Trump’s first term often went in the opposite direction.) Sure, we don’t necessarily look to ads for moral clarity, but they have always been a reflection of who we are as a culture–and what we’re willing to accept. But we shouldn’t accept this. –Rebecca Carroll AND:

THE GOAT TV MOM. FIGHT ME. (VIA YOUTUBE)

WE'LL ALWAYS HAVE FIJI. (VIA GETTY IMAGES)  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

It's Been Juneteenth All Year Long

June 18, 2025 Greetings, Meteor readers, Tomorrow is Juneteenth, so our offices (and maybe yours) are closed. But we couldn’t shut down our laptops without leaving you with a little bit of relevant reading and listening. Today Rebecca Carroll walks us through a year that, in spite of it all, has been culturally Black as fuck. Afterward, if you feel like luxuriating a little longer, read six incredible women on what they believe is the true meaning of Juneteenth. And of course, it wouldn’t be a celebration without hearing from Opal Lee, the “grandmother of Juneteenth,” who spoke with Brittany Packnett Cunningham a few years back about her relentless work to make this holiday a reality. Our thoughts are with Ms. Opal this week as news recently broke that she will not be leading the annual Walk for Freedom in Fort Worth, Texas, due to health complications. Remembering it’s a we thing, Shannon Melero  The Black Cultural Abundance of JuneteenthThis year, for me, Juneteenth started on February 9.BY REBECCA CARROLL  STILL THINKING ABOUT HIM (VIA GETTY IMAGES) I’ve watched it four times. Every time it’s given me something different. But what it has given me overall—in its multi-layered, legacy-laden, undeniably art-centric symbolism—is the assurance that one thing Black folks are always gonna do is find our freedom reflected in each other. I’m talking about Kendrick Lamar’s halftime show at Super Bowl LIX. It became the most-watched halftime show in history, drawing in more than 133 million viewers, and it felt not only like a call to action—because “sometimes you gotta pop out and show”—but also the very best of what Juneteenth invokes for me. Black folks’ relationship with America is obviously fraught. The country was built on our backs. Slavery is as foundationally American as the Super Bowl. And Juneteenth is, ostensibly, about American freedom. But even after the Emancipation Proclamation, Black Americans were still widely not considered to be free civilians, and that is why we continue to seek that freedom out in and for each other. After tennis star Coco Gauff won the 2025 French Open earlier this month, she said, “Some people might feel some type of way about being patriotic, but I’m definitely patriotic and proud to be American. I’m proud to represent the Americans that look like me.” And that was also the beauty of Lamar’s show—he could have easily declined to perform at such a mainstream Americana spectacle. Instead, he used it as an opportunity to reconfigure the American flag through the formation of his all-Black backup dancers, who wore red, white, and blue. Recently, when a young Black woman asked me how I write for my specific audience of readers, I said, “The same way Kendrick Lamar just performed the Blackest-blackety-black halftime show performance at the Super Bowl, for his specific audience of viewers, Black folks.” Because we know how to find each other, and speak to the insides of one another. It’s in the tradition of call-and-response, of ancestral homage, dignity, and legacy. It’s in our DNA. And it is an aegis of Black cultural jubilation in a year of targeted demoralization—when Black historic landmarks, Black museums, Black books and course curricula, and DEI initiatives are being defunded, denigrated, and dismantled.  GAUFF WITH THE ROLAND GARROS TROPHY WHICH SHE LATER AND HILARIOUSLY REVEALED IS NOT THE TROPHY CHAMPIONS GET TO TAKE HOME. (VIA GETTY) In the months after Lamar made the call, those responses have kept coming. Next came Ryan Coogler’s supernatural horror movie, “Sinners,” which both killed at the box office and earned glorious reviews. Like the Super Bowl show, “Sinners”—which follows twin bootlegging brothers who return to their Mississippi hometown to open a juke joint—is kaleidoscopic and heady, containing layers upon layers of historical references and truths. Amid recent indignities, Coogler managed to give us something rapturous, restorative, and unwavering in its tribute to Black freedom, Black love, and Black ingenuity. And then came Beyoncé’s “Cowboy Carter and the Rodeo Chitlin’ Circuit Tour,” an all-stadium concert tour celebrating her Cowboy Carter album, which explores the Black roots of country music (another quintessentially American institution). Yes, Beyoncé is an extraordinarily talented and iconic artist. But what has stood out the most to me about the Cowboy Carter tour is not Beyoncé herself but the way her daughter Blue Ivy, with every bit of her badass, 13-year-old self, has showed out to perform with her mother onstage, giving a kind of “fuck-you”-fueled intensity well beyond her years. To me, Blue Ivy represents the collective power and tenacity of Blackness, and I imagine is exactly what the ancestors had in mind when they thought, We gonna call it Juneteenth, and then we gonna do whatever the hell we want to on this day forward from heretofore.  CAN WE GET A YEE-HAW? (VIA GETTY IMAGES) And then there was The Met Gala. While I have real criticisms about the event as the standard of what constitutes haute fashion, and about its curated exclusivity (read: whiteness), I couldn’t help but feel like this year’s theme, “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style,” was another response to Lamar’s call. Inspired in part by Black scholar Monica L. Miller’s book, Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Style of Black Diasporic Identity, all our fave fancy Black folks walked that blue carpet wearing the fiercest looks, channeling the very essence of Black elegance, just like the one that Black folks have historically created for Juneteenth celebrations.  SO...ABOUT THAT ALBUM? (VIA GETTY IMAGES) After that, the ancestors came through…again: It was as if Annie, the Hoodoo healer from “Sinners,” gathered together a very particular recipe of roots and herbs to help conjure up some very large flames on a very specific plot of Southern land. It’s not nice to say, but when the largest surviving plantation mansion in the South burned to the ground on May 15, my first thought was, “Well, you shouldn’t have been enslaving people.” The demise of Nottoway Plantation in White Castle, Louisiana—which, like many plantations, had become a popular wedding venue—was reportedly caused by an electrical fire. Whatever the case, for it to happen during this run of Black cultural ascension seemed like poetic justice, and needless to say, the Black memes were delicious. There are many more examples—Amy Sherald, Lorna Simpson, Rashid Johnson, and Jack Whitton all having solo art shows this year; Audra McDonald being a classy boss bitch, and giving an utterly singular “Gypsy” performance at the Tonys; Rihanna continuing to populate so glamorously—but given where we are in this moment, it feels right to end with Doechii’s speech at the BET Awards last week. Because ultimately, Black freedom has always meant getting other people free, too. Doechii, who won the award for Best Female Hip-Hop Artist, chose to use her platform during the live broadcast to speak out against the ICE immigration raids happening in Los Angeles. “These are ruthless attacks that are creating fear and chaos in our communities in the name of law and order,” she said. “I feel it’s my responsibility as an artist to use this moment to speak up for all oppressed people: for Black people, for Latino people, for trans people, for the people in Gaza.” Juneteenth, which became a federal holiday in 2021, is about Black freedom. But it’s also about the function of freedom itself.

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

A Night of Black Creativity

May 6, 2025 Hey there, Meteor readers, Hearty congratulations are in order for Meteor collective members Dawn Porter and Tanya Selvaratnam, both of whom are nominated for News and Documentary Emmys this year: Porter for The Sing Sing Chronicles and Documenting Police Use of Force; and Selvaratnam for Love to the Max. Watch if you haven’t! In today’s newsletter, we’re strolling down the blue carpet of last night’s Met Gala with Julianne Escobedo Shepherd—and taking a moment to celebrate midwives. Still thinking about this, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON CARDI B AND HALLE BERRY. NO NOTES. (VIA GETTY IMAGES) Fashion’s dandiest night: Whatever your feelings about the Met Gala, this year’s theme, Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, was an important one. It was selected by Costume Institute curator Andrew Bolton last year after he read the 2009 book Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, by Barnard professor Monica L. Miller, now chair of the college’s Africana Studies Department. Inspired by its deeply researched history of the way formerly enslaved Black people reclaimed the frippery they were forced to wear into their own distinct style, Bolton asked Miller to become the Costume Institute’s first guest curator in his ten-year tenure. The exhibit itself lasts for nearly half a year, long after the last bit of carpet is rolled up. Superfine looks at the lineage of Black style in “the Atlantic diaspora,” and cites Zora Neale Hurston’s “Characteristics of Negro Expression,” an essay from 1934. “The will to adorn is the second most notable characteristic in Negro expression,” Hurston wrote. “Perhaps his idea of ornament does not attempt to meet conventional standards, but it satisfies the soul of its creator.” In other words: Black fashion evolved as a form of resistance against the way white culture expects Black people to be, but it doesn’t matter whether the clothes please anyone but the wearer. Aesthetically speaking, this year contained the best fashion at the Gala in years, its “tailored for you” dress code encouraging attendees to show up and show out as themselves. Co-chair Teyana Taylor wore a long red cape embroidered with the words “Harlem Rose,” created by costume designer Ruth E. Carter, who in 2018 became the first Black woman to win an Oscar for Best Costume Design, for Black Panther. Rihanna donned a deconstructed suit—part jacket, part bustle, part waist-as-lapel—its regal pinstripes channeling the spirit of Ida B. Wells, assuredly strutting into her newspaper job at the New York Age in the 1890s.  DO WE THINK SHE'S HIDING R9 UNDER THAT HAT? (VIA GETTY IMAGES) While the glitter of the Met Gala may seem out of touch in these violent times, it feels significant that Black creativity was celebrated at such a major institutional event, in a moment when institutions are being all but purged of Black people and other people of color. We’ve already seen how the Trump administration’s blatantly white supremacist agenda has affected the Kennedy Center, all cabinet-level departments, and state universities; he has promised to next come for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, PBS, and other government-funded institutions that bring alive the history of Black and brown people. Those institutions have only just begun to help this country grapple with its historical atrocities; now, thanks to the administration’s war on what it derisively refers to as “DEI,” the small progress that’s been made is being literally erased. Don’t just talk about it, be about it, goes a common phrase in African American Vernacular English (AAVE). The long national project of what that means politically is being cut off at the knees, thanks to these attacks on Black history in classrooms, libraries, government websites, and museums. So it’s huge that “fashion’s biggest night” at the country’s most renowned art institution was about Black history and Black people reveling in Black fashion as resistance. It was emphasized across every major publication, every tabloid and blog, and all over every social feed—Black fashion history everywhere. As Professor Miller put it to Lala Anthony in an interview on the carpet last night: “I’ve never had such a big classroom.” –Julianne Escobedo Shepherd AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

The Wonder of Amy Sherald

Ordinary Black life is extraordinary in the artist’s first major mid-career museum survey.

By Rebecca Carroll

Last month, The New Yorker featured a breathtaking portrait on its cover by celebrated Black American artist Amy Sherald. First painted in 2014 and titled “Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance),” the portrait of a young Black woman wearing a bright red hat is the same piece Sherald later submitted in a competition at the National Portrait Gallery. She won the competition, which caught the attention of former First Lady Michelle Obama, who then personally chose Sherald to paint her portrait for the National Portrait Gallery—making the Georgia native the first Black woman artist to be selected for an official presidential portrait. The Obama painting changed the entire trajectory of Sherald’s career, and since then her figurative grayscale portraits have been shown in public and private collections around the world.

Now, Sherald is having her first major museum survey at The Whitney Museum of American Art, called American Sublime, a title borrowed from the poet Elizabeth Alexander’s book of the same name. I’ve known and admired Sherald for years, and I was thrilled to sit down with her to talk about her work in this truly transcendent exhibition.

Rebecca Carroll: The last time we saw each other in person was pre-Michelle Obama portrait, when we randomly ran into each other on the street in Brooklyn. And here we are today to discuss your first solo exhibition at The Whitney. How are you feeling?

Amy Sherald: I told a friend last week, “I don’t know, I just feel emotional.” And she’s like, “Well, you’re getting used to belonging to the world, and not just to yourself.” Hearing that made me want to cry, and I left her a voice text, and said, “Okay, I’m sitting here holding back tears because I am a thug and I do not like to cry. But that’s exactly what I feel like.”

It’s a lot! The show is also set against a backdrop of political turmoil in America, particularly in regards to race, and actually not dissimilar to what we were experiencing when we last saw each other. At that time, the height of Black Lives Matter, I had written a piece for the LA Times, saying “Even as we see images of what most of us already know, that police violence against Black people in America is occurring with vicious regularity, something remarkable is materializing in its wake. We are also bearing witness to a pronounced moment of Black cultural ascension.” How has your work been impacted by eras of Black cultural ascension versus centuries of Black oppression?

My work was essentially born out of the desire to free myself from a history of oppression, but also in celebration of these eras of enlightenment. What I want the viewer to experience, and I say this in the exhibition [statement], is “the wonder of what it is to be a Black person.” I’m no longer religious, but I speak about this in that language of flesh and spirit—because part of us always has to be activated [in fighting oppression].

Right, exactly. I know you consider yourself as much a storyteller as an artist. As Black storytellers, I feel like we never make anything without parts of each other within us—intergenerationally, ancestrally, futuristically. But when the work goes out into the world and starts to belong to non-Black people, I sometimes feel these waves of protectiveness about it. Do you ever feel that way about your work?

I want the work to belong in the world because it was the only way that I could figure out how to counter whiteness, and the way that everything is saturated with it, comes from it, and evolves around it. My response to that is to make something that’s just as universal, and that can be consumed in the same way, because then [white people] are going to be consuming it in the same way that I had to consume Barbie, and all of these other things.

A pointed example for me was when your portrait of Breonna Taylor was on the cover of Vanity Fair, and it felt so unjust to me that suddenly white people were allowed to look at her in this way that we had seen her all along. Did you feel any conflict about that specific piece?

I didn’t, because of how it started. It started with Ta-Nehisi [Coates], and I trusted him and his vision. Maybe if the call had come from somebody else, then yes, but because it was Ta-Nehisi, no.

To clarify for our readers, Coates was the guest editor for that particular issue of Vanity Fair, and so that makes a difference, for sure. Now that the portrait is part of this exhibition at The Whitney, what has been the broader response to it?

A lot of people, of all races, are moved to tears by it. After I first finished it, I was really just thinking about how I’ve made this portrait, we’ve photographed it, it’s been on the cover of Vanity Fair, and now it’s in my studio. Now what can it do? I started some conversations, and it ended up being acquired by the National Museum of African American History and Culture. And now there’s a Breonna Taylor Legacy Fellowship and Breonna Taylor Legacy Scholarships for undergraduate students and law school students [at the University of Louisville, in Louisville, Kentucky, where Taylor lived; the fellowships are funded by proceeds from the portrait’s sale]. So if a student is doing anything in regards to social justice, whether their major is political science or art, they have an opportunity to get this scholarship. And then if a student is in law school and wants to work expungement [when a criminal record is erased or made unavailable for public access] cases in Alabama, which pays nothing, then here’s $12,000 to get you through your summer.

Does the idea that Black artists do work for each other resonate with you?

I feel like we make what we make because we are who we are. My mom told me this story about myself, and it stuck with me because I think my work sits in the world in the same way. [When I was a child] sometimes when we had dinner, I would just randomly get up and walk around the table and touch everybody on their shoulder and say, “I love you.” I would go all the way around, and then come sit down and finish my dinner. I think these portraits are “I love yous” out in the world to affirm anybody who is willing to see past the exterior and go deeper into their experience of what it means to be a human.

I love that story. And what do you experience when you look at your work?

I feel like the work sits in The Whitney, and there are words on the wall that explain it, but that work is me—somebody who was once a people pleaser and had a problem saying no, someone who doesn't like conflict or confrontation. My personality made that work.

I would never have looked at your work and thought, “These pieces were made by someone who had a problem saying no.” Are there specific things in the pieces that signal that to you?

I guess that’s where the beauty comes from, because the work doesn’t yell at you. It speaks to you nicely. If you feel uncomfortable in the presence of a Black person, this work will make you think, “Okay, well, maybe I don’t need to grab my purse. I might feel safe in the elevator with this guy.” It speaks to people that way. I went to Catholic school from K through 12, and was always one of two or three Black kids, so I have a lot of patience. I learned a lot of, “Let me explain to you why you can't say that.” Versus my friends that went to all-Black high schools, where it’s just like [gestures taking her earrings off], “Let me tell you…”

But you feel differently now, right? You’re in a different place. How do you think that will affect your work moving forward?

I’m not sure how the work is going to evolve to match who I am now, which is somebody who’s stronger, who doesn't mind saying no, and will look at you while you feel uncomfortable with my answer. I am excited because everything that I’ve made in this show has been living in my head for 20 years.

Does it feel like a kind of excavation in that way?

It feels more like a birth than an excavation. When I think about Black American art history and just our legacy within the larger canon, I feel like we don’t or can’t function on the same timeline as everybody else. It still feels like the beginning of something, this moment of myself, Rashid Johnson, Lorna Simpson, and Jack Whitten [all currently having museum shows]. It feels really great despite everything that’s happening. The art world is representing the world that we want to be—the real world right now.

What happens next for you?

I’m hoping that this show will make it into the National Portrait Gallery without having to make any compromises based on who’s sitting in an office at the White House. And I don’t mean, “Well, if I can’t have this painting of two men kissing and a trans person, then I’m not going to do the show.” I feel like that would be a mistake. I feel like it’s a mistake to step down from boards just because [Trump] wants to take over the Kennedy Center. Now more than ever, I feel like it’s important we be in those rooms and not shutting down the conversation. I think the bigger moment would be the work being in the Smithsonian Institution and people coming there to look at American history and Presidents, and then walking into my exhibition.

Whatever the fate of the work in this show, one of the things that really came through as I was walking through the exhibit, just like the way you used to walk around your family’s dinner table and tell everybody you love them—all of these people are taking care of each other, and I felt tapped on the shoulder and loved by every one of them.

Exactly as you should have felt.

Netflix's Adolescence Isn't About Race, Except Maybe It Is

The hit show provokes an empathy that Black boys seldom get

By Rebecca Carroll

Everyone is talking about Adolescence, the new Netflix drama that tells the harrowing story of a 13-year-old boy who is accused of killing his classmate, a girl named Katie. As a mother, I watched it as a cautionary tale about the perils of violent incel culture on the still-developing brains of young boys. But as a Black cultural critic who is also the mother of a Black boy, it also made me think about who we feel empathy for, and who we do not.

To be clear, I loved Adolescence. Each episode is shot in one remarkable take, every scene strung together like a grievous aria. The effect is gutting. At the center of the show is 13-year-old Jamie Miller (Owen Cooper), a baby-faced schoolboy with alabaster skin, brooding eyes, and a sullen British lilt. Jamie lives with his working-class family in the small town of West Yorkshire, England, and has been accused of the stabbing murder of his classmate. There are no spoilers to be had—damning video evidence is revealed in the first episode. The rest of the series unfolds the devastating aftermath of Jamie’s crime; the unraveling of his family following his arrest and incarceration; and the painstaking path to understanding his motivations.

It is a path paved with compassion. Jamie is presented as a victim of the manosphere, spending all those unsupervised hours holed up in his room, delving deep into a misogynist world online and on social media. By the end of the series, I was still somewhat rooting for this white boy who, yes, was a target of cyberbullying and the coded emoji world of Instagram, but who also committed a violent murder. This show made me worry about men, and I never worry about men. But my empathy speaks volumes about how we are all conditioned to receive and accept the way this boy is presented—and the fact that he is not demonized, a grace seldom offered to young Black boys.

According to the show’s co-writer and co-creator, Stephen Graham, Adolescence was inspired by an article he read about a boy who stabbed a girl to death, along with several other news stories about violent crimes committed against girls by young boys across Great Britain. He didn’t mention race (although, as a mixed-race person, Graham is no stranger to racism). But members of the very manosphere at the core of Adolescence have been quick to make its premise about race, spreading misinformation that the show was based on the murder of three young girls at a Taylor Swift-themed dance party in Southport, London last summer. The perpetrator in that case was 13-year-old Axel Rudakubana, who is Black. Despite the fact that production on Adolescence was well underway when those murders took place, right-wing influencer Ian Miles Chong took to X to accuse the show’s creators of “race-swapping” as an act of “anti-white propaganda,” a false claim that was promptly endorsed by X owner Elon Musk.

There are similarities in the stories: Rudakubana struggled with mental health issues and was also being bullied. He had even called a welfare hotline asking for help about what to do if he had homicidal ideations. But the media coverage of his case was short on the kind of empathy we feel for onscreen Jamie, whose first utterance is a terrified, “I’ve done nothing wrong.” Instead, the headlines in Rudakubana’s case went straight to describing him as an “evil killer,” and a “recluse teenage loner, obsessed with violence” who was on “a long path to murder.”

Had the creators of Adolescence cast a Black boy in the role of Jamie, the audience may well have perceived him with the same built-in bias that the media showed toward Rudakubana. But it might also have gone a long way in helping to extend the kind of empathy that Black boys deserve, too—a moral restitution that goes far beyond good television.

The “Recurring Lies” We Learn in School

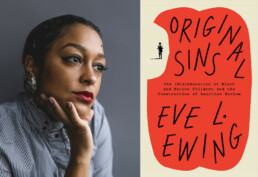

As our country marks Black History Month by banning books about race from classrooms, writer Eve L. Ewing looks at the long, complex “miseducation” of Black and Native children.

BY REBECCA CARROLL

AUTHOR EVE L. EWING WANTS YOUNG PEOPLE TO “UNDERSTAND THEIR OWN RADICAL POWER."

It’s been less than a month of the second Trump administration, and already in its crosshairs is the Department of Education. Trump has pledged to abolish it, issued an executive order threatening to defund schools engaging in discussions around race and oppression, and has empowered Elon Musk, a white male billionaire who grew up under the racist apartheid system of South Africa, to cancel $900 million in research grants. If there is a next level of “hope,” we need it now—and no one embodies hope, especially when it comes to education, more than poet and scholar Eve L. Ewing. Her new book, Original Sins: The (Mis)education of Black and Native Children and the Construction of American Racism, approaches the issue of disparity in education—specifically for Black and Native students—with the revelatory question of, “What if American schools are doing exactly what they are built to do?”

From the earliest efforts to offer schooling to formerly enslaved Black people—efforts that were met consistently with questions of whether or not Black people were human enough to be educated—to the compulsory boarding school attendance of Native children with the aim of “civilizing” them, Original Sins unearths the DNA of America’s education system, and lays bare the ways in which our knowledge has “been impacted, and to some degree, severed by colonialism.” And as Trump cuts DEI initiatives in American universities and colleges, one note from the book resonates: Schools, Ewing writes, “have never been for us.” But, she continues, regarding the education system as a whole, “The good news is that people made it, and people can unmake it—and make new things.”

Rebecca Carroll: It seems that from the start, the educational attitude toward Black folks was: We’ll give you subpar resources, but will (mostly) leave you alone as long as you stay away from us (white folks). While for Native Americans, it was: We’re going to steal your children, and destroy all their cultural ties to you. Why were the educational strategies used against Black folks and Native Americans so different from one another? Or were they?

Eve L. Ewing: The United States was founded on land that was violently stolen from the Native people who had lived here since time immemorial, and that land was tilled by enslaved Africans who were stolen from their homelands, degraded, and treated as property. Those foundational thefts enriched the nation at the expense of the lives, land, and dignity of Black and Indigenous peoples. And those actions didn’t happen in one discrete moment—they continue to reverberate in the world we live in today.

So in order for the country to sustain itself, it has required an intellectual underpinning that justifies those evils. It requires a set of recurring lies, to make it all seem okay. And that’s where schools come in: a place to make the lies seem real. Three of those lies that I talk about in the book are: the lie that Black people and Native people are intellectually inferior, the lie that our bodies and our children’s bodies inherently require more discipline and control, and the lie that we are destined for economic subjugation, that it’s our fate in life to lie at the bottom of a capitalist hierarchy.

There are ways that anti-blackness and anti-indigeneity use the same weapons, but there are indeed ways that the strategies diverge. And the reason for that is that white supremacy has historically needed different things from us. It has needed Black people to be subservient, and it has needed Native people to be gone. That’s how I would put it simply.

RC: What do you think is the responsibility of educators who began their careers when the official default was white supremacy? Is there a process of undoing (not a punishment) that needs to occur for teachers of all races who, for perhaps decades, taught children of all races through the lens of racial hierarchy?

ELE: It’s a hard question. I think it’s important to begin by centering ourselves in relationships. All of us—in our personal lives, in our work lives—have had moments when we thought we were doing our best, and it’s made clear to us that the people we loved were not served by our choices. When that happens, we have a choice to make: Do we choose to be defensive, or do we take the opportunity to be reflective? If someone takes the time to try to teach you to do better, to be better, that’s an act of love. Are you able to receive that love, or not? Are you able to be accountable for your actions? That’s a question for folks to ask themselves. At the same time, we need to be making space for people who are radically caring and transformative to enter the profession.

RC: Speaking of undoing racist teachings, you cite the work of scholars Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, who disparage the “easy use” of the word “decolonize.” They note that in recent years, social justice activists have suggested “decolonizing” certain spaces and ideology…but in doing so have actually trivialized the word. Is it not possible, though, for an easy use of a term to also be effective?

ELE: I think the question has to be, effective for what? …Real decolonization is not easy, and if a violent colonial institution continues to profit from harms against Indigenous peoples, having a single book or training or workshop or affinity group and then saying that that is “decolonizing” could be not only misleading—it could be actively dangerous, because it gives people a facile representation of what decolonization is. It reminds me of a moment in 2020 when the university where I work declared that they were committed to anti-racism, which could not have been further from the truth. So I see it as less of a scholarly conversation, and more of a “say it with your chest” conversation, or a “don’t just talk about it, be about it” conversation.

RC: In a recent piece for In These Times, you wrote: “It’s not enough to be afraid of the laws and rules we don’t want to see in schools.…Who are the young people you love most….What are the values you hold dear that you want desperately for them to understand, to inherit?” To your young beloveds, or simply to your readers, what are the values you hold dear that you want desperately for them to understand, and to inherit?

ELE: Thank you for that question! I want the young people in my life to understand their own radical power to love: to love themselves, to love others, to love the lands and waters and more-than-human relatives, and to understand how strong we are collectively when we turn that love into action. I want them to voraciously seek out stories in all forms and to see themselves as storytellers. And I want them to understand Chicago history and the history of great Black artists who shaped culture as we know it.