A Generation of Women Held Back

|

Dear Meteor readers, Two years ago this week, the United States and Great Britain withdrew troops and diplomatic resources from Afghanistan as the Taliban claimed rule in that country. Since that fateful day in 2021, over 1 million people have fled Afghanistan and some have found themselves displaced, detained, and separated from their families. Many, like Zaki Anwari, died attempting to escape; the devastating images of people hanging from planes while they were taking off remain seared into our minds. Then there are those who stayed or were left behind and have seen their nation impoverished and their rights curtailed. In today’s newsletter, we look at what the last two years have been like for Afghan women and girls—along with that big Trump indictment, some good news in Massachusetts, and more trouble in Texas. With love, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON...IN AFGHANISTAN FAMILIES LINE UP TO BE TAKEN OUT OF KABUL THE DAY AFTER THE TALIBAN RETURNED TO POWER. (IMAGE BY MASTER SGT. DONALD R. ALLEN VIA GETTY IMAGES) Not a “comfortable and prosperous” life: In June of this year, Taliban leader Hibatullah Akhundzada shared a message which claimed that “The status of women as a free and dignified human being has been restored and all institutions have been obliged to help women in securing marriage, inheritance and other rights.” But the difference between reality and propaganda is stark. Beginning in early 2022, girls were banned from attending school beyond the 6th grade. As the year rolled on, women were banned from universities, government jobs, non-government jobs, and eventually all public spaces. Women who want to leave their homes are required to wear burqas and must be accompanied by a male relative. If a man isn’t available, as can easily be the case for widows and divorcees, a woman must remain out of sight. The implications of this oppression are far-reaching. Not only are entire generations of women being denied rights, resources, and access to education, but the national economy is suffering as the countries Afghanistan previously relied on for aid have largely withdrawn their money because of the Taliban’s human rights violations. That loss of aid coupled with several years of drought-like conditions has triggered a near-famine in most of the country. Unable to work outside of the home, women are left to starve or resort to extreme measures to survive. Those who attempt to fight back, like the women who protested the banning of beauty salons last month, are met with more violence. And yet the women of Afghanistan continue to fight. A new report from Sky News reveals that some have created “underground” businesses to help themselves and others earn an income. One business owner who started a secret craft shop used the funds from her business to open an underground school for girls; it now services 200 students. “I don't want Afghan girls to forget their knowledge and then, in a few years, we will have another illiterate generation,” she told Sky News. But without proper government infrastructure or international aid, even the most resilient Afghan woman is up against insurmountable odds. So are some of those who managed to escape the country: In the UK, Afghan refugees are now facing homelessness after a program which paid for their hotel stays ended; those who settled in America dealt with a similar housing crisis last year. The road to the “comfortable and prosperous life” that Akhundzada claimed Afghan women already possessed is as of yet uncharted. It certainly cannot be obtained with the Taliban in power, but with no other group remaining to challenge them the Afghan people have been left with few choices. This morning in Kabul, Taliban soldiers celebrated their triumph with a parade. Click here to donate to relief programs in Afghanistan. For more on Afghanistan feel free to revisit our interview with two Afghan journalists, and our talk with Afghanistan Women’s National team captain, Farkhunda Muhtaj.

AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? This newsletter was written by Shannon Melero and Bailey Wayne Hundl.

|

![]()

The Rhymes That Changed Us

11 Women on Their Hip-Hop Click Moment

By Rebecca Carroll

Hip-hop as a genre is complicated. But at its core, it’s about bearing witness to the world and telling a story directly from that personal vantage point. Whether they be stories of revolutionary rage, tender triumph, sheer joy, or all of the above, the hip-hop canon is undeniably rich. This year marks the 50th anniversary of hip-hop as an art form, and to celebrate, we asked our favorite creatives to share a lyric from one song that impacted them in some profound way.

It could all be so simple

But you’d rather make it hard

Loving you is like a battle

And we both end up with scars

I write to music. I look for songs that open me up to the emotions I’m writing. These lyrics are so deep and gutturally poetic. I put this song on repeat to write the “fourth quarter” of Love and Basketball. I have literally heard it over a thousand times. And it rocks me still. —Gina Prince-Bythewood, filmmaker

And since we all came from a woman

Got our name from a woman and our game from a woman

I wonder why we take from our women

Why we rape our women, do we hate our women?

I spent some time with Pac before this song was written. I was in a black feminist rock group called Subject to Change. He would come to my band rehearsals, and afterwards we would share deep and heavy conversations about the depiction of Black women in Hip Hop. We also talked about the incredible women of The Black Panther Party. My heart expanded when he wrote these powerful lyrics. He was such a beautiful man inside and out. —Cree Summer, actress, singer/songwriter

You ain’t a bitch or a hoe

I've been a hip-hop fan since I was a little girl, but I've always resented how misogynistic the music can be. I didn't have the greatest understanding of why that was when I was small, but I knew that our men were using it to call us mean names and I didn't like that. When I was about nine, Queen Latifah released “U.N.I.T.Y.,” a powerful clapback towards sexism in both hip-hop music and the Black community. I was entranced. Latifah was so strong, so beautiful, and she was standing up for us. It's one of my favorite songs to this day. —Jamilah Lemieux, cultural critic

Hypocrites always wanna play innocent

Always wanna take it to the full-out extent

Always wanna make it seem like good intent

Never wanna face it when it's time for punishment

I know you don't wanna hear my opinion

There come many paths and you must choose one

And if you don't change then the rain soon come

See you might win some, but you just lost one

She is perfect here, and ruthless. —Danyel Smith, author

I push my seed in her bush for life

It's gonna work because I'm pushing it right

If Mary drops my baby girl tonight

I would name her "Rock n' Roll"

— “The Seed,” The Roots ft. Cody Chestnut

When my husband Chris (a former DJ, and a pretty serious hip-hop head) and I were first dating, he made a number of playlists for me. Often I’d listen to them on my own, at the gym or whatever, but one time he made a playlist for me that we listened to for the first time together in the car on our way out of town for a weekend getaway. When “The Seed” by The Roots with Cody Chestnut—which I’d never heard before—came on, I was immediately feeling it. But when I heard this hook, I absolutely fell in love with it (and, to be honest, with Chris). I turned to him and said, “That’s the most beautiful thing I’ve ever heard.” Reader, it is of no small significance that on our first date, before we were even brought menus, I’d told him I wanted to have a baby within the next year or two, and then said, directly, “So what are you looking for in a relationship?” He responded, unrattled, “Why don’t we have dinner first.” He planted the seed in my bush for life 10 months later. We named him Kofi. —Rebecca Carroll, writer and Meteor editor-at-large

Word up, mommy. I love you — Ghostface

I sit and think about

All the times we did without

I always said I wouldn't cry

When I saw tears in your eyes

I understand that daddy's not here now

But some way or somehow, I will always be around — Mary J. Blige

— “All That I Got is You,” Ghostface Killah ft. Mary J. Blige

Ghostface is in my top 10, but this song is easily in my top five. When I hear the raw honesty, vulnerability, love, and pain in his voice, I cry thinking about my three sons. Though Pretty Toney’s circumstances and lived experiences are different from my sons’, I listen and imagine how they are processing their dad’s death, his irrevocable absence, in the quiet hours of the night when they’re in their beds.

Do they cry? Are they angry? Will they heal? What will they remember? Am I enough?

It is excruciating for me to live this life without my husband, my best friend, my greatest love. It pains me to think about my sons navigating this life without their father, the man who loves them most in this world—the person who would have laid down his life for them without thought.

But I hope every day that my sons know I’m doing my best and that I love them with every cell in my body and every beat of my heart. I hope they know I will always, always be around—in this life and the next. And that I will fight beside them to make it through.

Thank you, Ghostface and Mary J., for this prayer. —Kirsten West Savali, VP Content at iOne Digital & cultural critic

Stuntin’ on these bitches out of motherfuckin' spite

Ain't no runnin' up on me, went from nothin' to glory

I ain't tellin' y'all to do it, I'm just tellin' my story

I don't hang with these bitches 'cause these bitches be corny

And I got enough bras, y'all ain't gotta support me

The pressure on your shoulders feel like boulders

When you gotta make sure that everybody straight

Bitches stab you in your back while they smilin' in your face

Talking crazy on your name, trying not to catch a case

I waited my whole life just to shit on ***

Climbed to the top floor, so I can spit on ***

My mom, who has been a preacher in The Bronx my whole life, would regularly tell kids in the congregation, “Great things have come out of The Bronx, so don’t let anyone stop you from doing what you want to do.” She gave me a similar sermon the first time I left home for college, but it was also the first time she went into detail as to all the ways I was about to discover how I was different from the students at my new predominantly white school. When I first heard this song, I felt such a swell of pride—not only because Cardi and I were from the same borough, but because it really captured how I felt about the journey to my own personal “top floor.” Plus it felt good to be honest that I also do certain things purely out of spite for people who told me I’d never get anywhere. —Shannon Melero, writer and Meteor newsletter editor

Yo, my men and my women,

Don't forget about the dean, Sirat al-Mustaqim

Talking out your neck sayin' you're a Christian

A Muslim sleeping with the gin

— “Doo Wop (That Thing),” Lauryn Hill

I remember the first time I heard this song. I was raised Muslim and there weren't any references to my religion in pop culture at the time. I felt so seen to know that an artist, especially Lauryn Hill, knew about Islam. And I was mesmerized by the way she wove it into a song about relationships and self-worth. I listened to the song over and over, and loved hearing it on the radio thinking (and hoping) how many people were noticing those same lyrics. I don't recall the exact moment or song that made me a music head, but putting these words down—this may have been the moment I realized the power of words. —Ayesha Johnson, Meteor director of operations

Pull up in the monster, automobile gangsta

With a bad bitch that came from Sri Lanka

— Nicki Minaj's riff on “Monster”

This lyric always hypes me up if I'm feeling nervous about performing as a DJ or in my work as an activist/advocate. As someone who is from that particular place and does a multiplicity of things that fundamentally, to me, are about care, building power, and creating joy in a world that often doesn't care for BIPOC and queer folks, I like the power of the lyric. It feels like she wrote that specifically for me. —Thanu Yakupitiyage (DJ Ushka), DJ & activist

I put my lifetime in between the paper’s lines

Prodigy’s vivid, cinematic lyricism struck a deep chord in me as a young poet coming of age in the ‘90s and as fate would have it, I later wound up authoring his memoir My Infamous Life with him. This line from “Quiet Storm” encapsulates so much about the power of storytelling—and reminds me of how, at its best, hip-hop transcends boundaries, unites us as a culture and force to be reckoned with, and has made so many poets' dreams literally come true. —Laura Checkoway, filmmaker

We used to fuss when the landlord dissed us

No heat, wonder why Christmas missed us

Birthdays was the worst days

Now we sip champagne when we thirsty

—“Juicy,” The Notorious B.I.G.

In 1996, I went to college a beleaguered student who had gotten into college by the skin of my teeth. I wasn’t a great student, but I had also felt deeply misunderstood and overlooked in my predominantly white suburban school. My life and Biggie’s life were not the same, at all. But his rags-to-riches anthem spoke to me at 18, a young woman of color with a chip on my shoulder and something to prove. His music had such an impact on me that I wrote my senior thesis on how to be a feminist and rap music fan. (tl;dr: my findings were inconclusive) A problematic fave, no doubt, but his music resonates with me to this day. —Samhita Mukhopadhyay, writer and Meteor editorial director

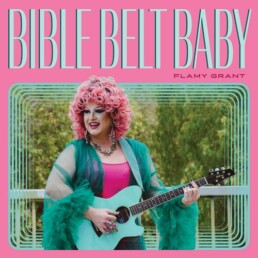

Serving Looks While Serving the Lord

Meet Flamy Grant, the drag queen with a chart-topping Christian music album.

BY BAILEY WAYNE HUNDL

Flamy Grant is a “shame-slaying, hip-swaying, singing-songwriting” drag queen from western North Carolina. Her name is a reference to 90s Christian pop star Amy Grant, and her album Bible Belt Baby centers on her journey as a queer person of faith—which, apparently, some people aren’t too happy about.

On July 26, infamous MAGA pastor Sean Feucht angrily tweeted about Grant, lamenting that “these are truly the last days,” and that Christian music from a drag queen was the “end goal” of the progressive Christian movement.

“End goal?” Grant tweeted back. “Baby, we’re just getting started. 😘”

And she meant what she said. Feucht told Grant that “hardly anyone listens or cares what you do,” so she rallied her fans on social media to get her songs on the Christian music charts. And by the next morning, her album had reached No. 1 on iTunes.

As a drag queen/queer Christian myself, I had to sit down with this diva and get into it all: the drama, the trauma, and what she hopes to give any Christian—both queer and the other kind.

Bailey Wayne Hundl: Over the last ten days, you have been in People, Rolling Stone, Billboard—when you put out your album, did you ever envision something like this happening?

Flamy Grant: Not to this degree. You know, I saw what happened with Semler, a good friend of mine, and they're the first out queer artist to hit number one on the [Christian] iTunes charts. So I knew that it would be a big deal if a drag queen got on the iTunes charts. But I just thought it would be a cool moment of representation. I would've been happy with that, but like, my gosh, to have a Rolling Stone article that I can now point to… It's crazy. It's massive.

When you started doing drag and mixing that with Christian music, was that your intention—to get as many eyes on it as possible?

My intention has been to have a career, so whatever it takes to pay my bills. That's been my intention.

And that's just the first rule of drag. Get your bag.

(laughs) Exactly. Yes. My second purpose and intention is to— I always tell people that I write for queer folks, specifically queer folks who grew up in evangelicalism or other high-demand religions who will resonate to that story of having to unburden yourself of a whole heap of oppression that was dropped on you. And then finding freedom, finding liberation, finding your sparkle.

You’ve been a worship leader in church since high school. What led you to add drag to that?

Well, the pandemic, honestly. I got super into drag in my mid-thirties. I've always been a late bloomer at everything because, you know, religious trauma. I mean, I didn't even come out fully until I was 28. So it took a few more years to really become ingrained in queer culture. So once I fell in love with drag, I was just all about it.

And the pandemic gave me the time. I live [in] this house with some housemates who are also musicians. So we started a livestream, like many artists did during the pandemic, where we would just sing cover songs every Thursday night to, like, 30 people on Facebook. I started showing up to those in drag and really that's where Flamy developed her chops, if you will.

[One day] my pastor asked me to give the sermon in drag…so I made a TikTok video to practice and gave a little [uplifting message] in 60 seconds while I was painting my face. And I woke up the next morning and it had completely blown up and gone viral. And I was floored at the responses: “This makes me feel so seen.” “It makes me feel so safe.”

And that inspired you to release a Christian album.

First of all, my record feels like a spiritual record, and I come from the evangelical world, so why not call it a Christian record? It's telling a spiritual journey. It's speaking to people who are still in the church. It's speaking to people who have oppressed queer people in the church. That's the audience that it's for, really. So it just made sense to put it in the Christian category.

I struggled with that a lot because the word “Christian” is so loaded in America—because it's been co-opted by evangelicals. I always like to make this point: Evangelicalism is a sect of Christianity. It is not representative of the entire faith. What we understand to be mainstream Christianity in America is not actually, like, historically Christian.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=feSr8mlljzU

One thing that queer people of faith get asked a lot is, “How do you reconcile these two disparate worlds?” But I'm curious: Why do you continue to reconcile the two worlds?

Well, I mean, first and foremost, I think the main reason is simple: It's representation. I don't see anybody else who's intentionally trying to be a Christian in the [contemporary Christian music] genre, trying to do that as a drag queen in particular.

And then, because I grew up the way I did, I know what it's like to be a kid who has just nothing to look at that looks or feels like me—to feel like you are such an anomaly and to feel like you are such a broken thing.

So knowing that I can be there, present, especially in such a visible way—because that's the thing about drag: It's a very visibly queer art form. You know, we can see a picture of a drag queen, but then if you get to spend 45 minutes with her, listening to her heart…to hear a full record where I'm talking about this stuff…that's gonna make [an impact].

And a good record, too, if you don't mind me saying.

Thank you! I don't mind you saying it at all. You can say it many times. I'm very proud of it.

Last question: If you could get just one thing across to the church, what would that be?

My answer might be a little skewed right now, because the past two weeks I've just been inundated and saturated with comments from Christians on the internet who make wild assumptions.

But my encouragement to Christians would be to just listen a little bit. Go listen to three of the songs on my record. And if you don't wanna engage with me, at least take that posture to queer people in your life. And if you don't know any queer people in your life: Yes, you do. You just don't know that they're queer yet.

Just push pause for just a little bit. I know you feel righteously compelled to speak. You feel educated about it because you've read six Bible verses. But there's a whole life story in each of us that I promise if you really hear—it's gonna have an impact on you. And it may not change your mind about homosexuality, but it may give you a window into a life that you would otherwise roll your eyes at or type a vomit emoji at.

Just listen as hard as you can for as long as you can. And see what happens.

The one thing Barbie never was

July 20, 2023 Come on, Meteor readers, let’s go party, After years of anticipation, debate, hot pink outfits, and hot pink lake water, the Barbie movie premieres tomorrow. In today’s newsletter, culture critic Scarlett Harris combs through the 64-year history of the controversial doll to understand the (potentially radical) reasons why she never became a mother. And because we know you are obsessed like we are, we’ve also assembled The Ultimate Barbie Reading Guide, covering everything from the doll’s accidental feminist legacy to her impact on Black and brown girls. But first, the news. Thinking pink, Bailey Wayne Hundl  WHAT'S GOING ONTexas women fight back: Three women testified yesterday as part of a 15-plaintiff lawsuit against the state of Texas for allegedly being denied life-saving abortion care due to the state’s draconian abortion ban. The ban, one of the most severe in the country, makes it a felony to perform an abortion, and doing so could result in a fine of up to $10,000, the loss of the doctor’s medical license, and up to a lifetime in prison. The suit brought by the Center for Reproductive Rights asks for the law to be temporarily blocked and for the state to clarify what constitutes a medical emergency that will allow for an abortion. One of the women who shared her harrowing experience on the stand was Amanda Zurawski, who first told her story to the Meteor last fall. Zurawski was denied the procedure, her life put at risk. “I survived sepsis, and I don’t think today was much less traumatic than that,” she said. Another plaintiff, Samantha Casiano, shared that she was forced to deliver her fetus even after learning it would not develop a skull or brainstem. As she told her story, she vomited on the stand, and the court had to go into recess. This hearing is nothing short of historic. According to the Texas Tribune, these women are likely the first to testify about the impacts of abortion bans on their bodies since 1973. Despite their courageous testimony, the state is pushing back, claiming the law doesn’t need to be amended and putting the onus instead on doctors. But that doesn’t change the fact that if these women win, Texans who need abortions will not have to go through what they did. AND:

LIFE IN PLASTICBarbie, Child-Free IconBY SCARLETT HARRISThere's only one thing this doll hasn't done. Why, exactly?  A BARBIE DOLL LOUNGES IN HER PACKAGING. (PHOTO BY DAVID BENITO/GETTY IMAGES) The opening scene of Barbie, the much-anticipated movie event hitting cinemas tomorrow directed by Greta Gerwig and starring Margot Robbie, is a parody of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. In it, young girls smash their baby dolls in favor of Robbie’s Barbie. Outfitted in the fashion doll’s original get-up of a black-and-white-striped bathing suit, cat-eye sunglasses, and permed bangs, Robbie stands in the center, a glamazon, signaling the dawn of a new woman. Barbie, the doll, was conceived by Ruth Handler, an executive at Mattel, in the 1950s. After observing her daughter, Barbara, for whom Barbie is named, assigning adult roles to her paper dolls, she came up with the idea—and modeled her creation after a doll based on a German comic strip chronicling the life of a sex worker, Bild Lilli. Before Barbie hit the market in 1959, dolls for girls were primarily babies meant to teach their owners the caregiving skills they would inevitably need for lives of housewifery and childrearing. But Barbie brought something new: She represented a wide range of fulfilling lifestyles outside of traditional feminine responsibilities. Barbie could be anything she wanted: an astronaut, an artist, even the President. But, in all these years, she’s never wanted to be a mother. Barbie’s impact has been widely debated, and Barbie leans into this. Is she a feminist icon or nightmare? But one thing cannot be denied: Since her inception, Barbie has been the main character of her own story. She was made to be someone rather than someone’s someone. And in keeping with Barbie tradition, the film’s fantastical Barbieland does away with traditional gender roles. Ken (launched as a boyfriend doll in 1961) lives in service of Barbie, even going so far as to be referenced as “and Ken” in his mugshot—a pure appendage, even if Ken doesn’t have one himself. In a reversal of the biblical creation myth, Ken is spawned from Barbie. “I only exist in the warmth of your gaze,” he says. And, unlike Barbie, he has no occupation—his job is literally described as “beach” in the film. The message was radical for its time: When the doll debuted, there were few images of female breadwinners. Women couldn’t even get a credit card in their own name without permission from a father or husband until 1974, almost twenty years after Barbie had enjoyed financial independence and career achievement in fields such as modeling (her first occupation), nursing (1961), space and aeronautics (1965 and 1966, respectively), surgery (1973) and Olympic gymnastics (1974). All those jobs become even more impressive when you consider that, canonically, Barbie is 19 years old. Maria Teresa Hart, the author of the book Doll, points out that her age at the time of her introduction would have put her on the precipice of two possible paths: marriage and babies or continuing her current lifestyle as a Career Girl with a bevy of friends. “That ambiguity is part of the attraction: she’s at this tipping point where she could make a variety of choices,” says Hart. “Every avenue is open to her.”  MARGOT ROBBIE AT A PRESS JUNKET FOR THE BARBIE MOVIE (PHOTO BY RODIN ECKENROTH/FILMMAGIC) And yet Barbie never travels down the avenue of parenthood, unless you count the amount of time she spent caring for her sisters, Stacey and Chelsea. (If, during your childhood, Barbie’s youngest sister was named Kelly: congratulations, you’re officially old and missed Kelly’s rebrand as Chelsea in 2011.) Barbie’s childlessness was intentional: Handler wanted to show her daughter that fulfillment can exist outside of the home. In the film, her open-plan, multi-story dream house is a dwelling for one—no child safety, no doors. “It’s very definitely a house for a single woman,” production designer Sarah Greenwood told Architectural Digest. Barbie’s other accessories weren’t made with would-be kids in mind, either—the Barbie Porsche convertible I had as a child definitely didn’t have a car seat, and the only baby in sight belonged to the much-maligned Midge, a visibly pregnant doll who was discontinued as Barbie’s bestie in 1967, only to reappear later as Barbie’s married mother friend sans baby bump (though she still angered conservative parents who thought she wasn’t coded strongly enough as a married woman). Documentary filmmaker Therese Schechter, who most recently directed the child-free doco My So-Called Selfish Life, expresses incredulity about Midge’s predicament. “No one has children in that world; why is Midge going to have a baby?” For some, Barbie might still just be a silly doll with an eternally perky and unattainable body. But, as Willa Paskin wrote, Barbie being child-free “remains one of the most radical things about her.” And in a country hell-bent on forcing more and more people to give birth, her childlessness takes on a new and refreshing meaning. As Robbie noted in Vogue, Barbie doesn’t have reproductive organs—which is probably why the elected representatives of Barbieland haven’t tried to police what she does in the Dreamhouse bedroom. Scarlett Harris is a culture critic and author of the book A Diva Was a Female Version of a Wrestler: An Abbreviated Herstory of World Wrestling Entertainment. You can follow her on Twitter @ScarlettEHarris and read her previously published work at her website, The Scarlett Woman.  WEEKEND READSTomorrow is the official premiere of the Barbie movie, so we’ve put together The Ultimate Barbie Reading Guide for everyone who loves—and hates!—the world’s most famous doll.

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Barbie, Child-Free Icon

There's only one thing this doll hasn't done. Why, exactly?

By Scarlett Harris

The opening scene of Barbie, the much-anticipated movie event hitting cinemas tomorrow directed by Greta Gerwig and starring Margot Robbie, is a parody of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. In it, young girls smash their baby dolls in favor of Robbie’s Barbie. Outfitted in the fashion doll’s original get-up of a black-and-white-striped bathing suit, cat-eye sunglasses, and permed bangs, Robbie stands in the center, a glamazon, signaling the dawn of a new woman.

Barbie, the doll, was conceived by Ruth Handler, an executive at Mattel, in the 1950s. After observing her daughter, Barbara, for whom Barbie is named, assigning adult roles to her paper dolls, she came up with the idea—and modeled her creation after a doll based on a German comic strip chronicling the life of a sex worker, Bild Lilli.

Before Barbie hit the market in 1959, dolls for girls were primarily babies meant to teach their owners the caregiving skills they would inevitably need for lives of housewifery and childrearing. But Barbie brought something new: She represented a wide range of fulfilling lifestyles outside of traditional feminine responsibilities. Barbie could be anything she wanted: an astronaut, an artist, even the President. But, in all these years, she’s never wanted to be a mother.

Barbie’s impact has been widely debated, and Barbie leans into this. Is she a feminist icon or nightmare? But one thing cannot be denied: Since her inception, Barbie has been the main character of her own story. She was made to be someone rather than someone’s someone. And in keeping with Barbie tradition, the film’s fantastical Barbieland does away with traditional gender roles. Ken (launched as a boyfriend doll in 1961) lives in service of Barbie, even going so far as to be referenced as “and Ken” in his mugshot—a pure appendage, even if Ken doesn’t have one himself. In a reversal of the biblical creation myth, Ken is spawned from Barbie. “I only exist in the warmth of your gaze,” he says. And, unlike Barbie, he has no occupation—his job is literally described as “beach” in the film.

The message was radical for its time: When the doll debuted, there were few images of female breadwinners. Women couldn’t even get a credit card in their own name without permission from a father or husband until 1974, almost twenty years after Barbie had enjoyed financial independence and career achievement in fields such as modeling (her first occupation), nursing (1961), space and aeronautics (1965 and 1966, respectively), surgery (1973) and Olympic gymnastics (1974).

All those jobs become even more impressive when you consider that, canonically, Barbie is 19 years old. Maria Teresa Hart, the author of the book Doll, points out that her age at the time of her introduction would have put her on the precipice of two possible paths: marriage and babies or continuing her current lifestyle as a Career Girl with a bevy of friends. “That ambiguity is part of the attraction: she’s at this tipping point where she could make a variety of choices,” says Hart. “Every avenue is open to her.”

And yet Barbie never travels down the avenue of parenthood, unless you count the amount of time she spent caring for her sisters, Stacey and Chelsea. (If, during your childhood, Barbie’s youngest sister was named Kelly: congratulations, you’re officially old and missed Kelly’s rebrand as Chelsea in 2011.) Barbie’s childlessness was intentional: Handler wanted to show her daughter that fulfillment can exist outside of the home. In the film, her open-plan, multi-story dream house is a dwelling for one—no child safety, no doors. “It’s very definitely a house for a single woman,” production designer Sarah Greenwood told Architectural Digest.

Barbie’s other accessories weren’t made with would-be kids in mind, either—the Barbie Porsche convertible I had as a child definitely didn’t have a car seat, and the only baby in sight belonged to the much-maligned Midge, a visibly pregnant doll who was discontinued as Barbie’s bestie in 1967, only to reappear later as Barbie’s married mother friend sans baby bump (though she still angered conservative parents who thought she wasn’t coded strongly enough as a married woman). Documentary filmmaker Therese Schechter, who most recently directed the child-free doco My So-Called Selfish Life, expresses incredulity about Midge’s predicament. “No one has children in that world; why is Midge going to have a baby?”

For some, Barbie might still just be a silly doll with an eternally perky and unattainable body. But, as Willa Paskin wrote, Barbie being child-free “remains one of the most radical things about her.” And in a country hell-bent on forcing more and more people to give birth, her childlessness takes on a new and refreshing meaning. As Robbie noted in Vogue, Barbie doesn’t have reproductive organs—which is probably why the elected representatives of Barbieland haven’t tried to police what she does in the Dreamhouse bedroom.

Scarlett Harris is a culture critic and author of the book A Diva Was a Female Version of a Wrestler: An Abbreviated Herstory of World Wrestling Entertainment. You can follow her on Twitter @ScarlettEHarris and read her previously published work at her website, The Scarlett Woman.

What the Hollywood strike means for labor

July 18, 2023 Hello hello, Meteor readers, As you may be acutely aware right now: We’re currently having the hottest summer of all time. In fact, yesterday was the hottest day the entire Northern Hemisphere has had in recorded history. (Mondays, am I right?)  In today’s newsletter, we’re looking at what the joint writer's/actor's strike means for the rest of us, as well as the largest oral history of activism from young girls. Cranking that fan, Bailey Wayne Hundl  WHAT'S GOING ONHot labor summer, cont.: The Writers Guild of America (WGA), representing more than 11,000 film and TV writers, has been on strike since May 2. And last Thursday, July 13, those writers were joined by the 160,000 members of the Screen Actors Guild (known as SAG-AFTRA). That’s right: Hollywood is looking at a double strike for the first time in 63 years. No Teds will be Lassoed and no Things will be Strangered—not until the networks are willing to negotiate with their workers (and not just kill trees to deny them shade). It could be easy to write off the actors’ strike as symbolic as actors are already mega-rich. But that is not so, hypothetical dissident! Michelle Hurd, vice president of SAG-AFTRA’s Los Angeles chapter, says that the number of SAG-AFTRA members who do not have consistent work has risen to 98 percent. “There’s a perception out there that everyone is doing great, that this career choice is lucrative for everyone, when that’s just not true,” Hurd told actor/writer Amber Tamblyn last weekend. “In reality, most SAG members are worried about making rent, let alone buying a home.” In order to make the rent between jobs, actors and writers rely on residuals, recurring payments based on a share of the profits earned by a particular TV show or movie—or at least, that’s how it works in theory. Historically, this led to even minor actors on major hit films and television shows receiving reasonable residuals for years after their projects had wrapped. But things look different in the streaming era. For example, Kimiko Glenn, who played Brook Soso in one of the first big streaming hits on Netflix, “Orange is the New Black,” shared one of her recent residual statements on TikTok; for all 44 episodes she appeared in, her residual compensation was $27.30. For comparison, Ben Haist, who appeared for two minutes as a background actor in 2011’s “Pitch Perfect,” shared that he still receives a residual check for $200-300 per quarter. In other words, the economics have become more challenging for workers in this industry. But that’s before the rise of AI, which threatens to make things worse: SAG-AFTRA Chief Negotiator Duncan Crabtree-Ireland shared that during negotiations, the networks proposed “that background actors should be able to be scanned, get paid for one day’s pay, and their company should own that scan...to be able to use it for the rest of eternity.” This would, presumably, include generating new scenes based on that character’s likeness—all for a paycheck of less than $200. All of this is just part of the reason these strikes matter to all of us, whether or not you’ve got anything to do with the entertainment industry. For one thing, the arts are a necessary part of a healthy and functioning society. (What would the pandemic have been without streaming TV?) But also, at a time when tensions around AI in the workplace are already rising, the writer’s/actor’s strike could be a watershed moment for all workers’ equity, one that lets employers know that employees deserve—and will demand—compensation for the labor that makes AI systems work. Studio executives have already claimed that their plan is to wait until union members “start losing their apartments and losing their houses.” If you’d like to keep that from happening, you can donate to the Entertainment Community Fund to keep striking workers afloat. Let’s hear it for the girls: An important report just dropped from UN Women at the Women Deliver conference in Rwanda—and the findings are jarring. Of the 114 countries surveyed, researchers found that not one had achieved true gender parity. What’s worse: Less than 1 percent of women and girls around the world live in a country with high women’s empowerment or a reduced gender gap—and on average, women only reach 60% of their potential in crucial categories like health, education, decision-making, and freedom from violence. (So maybe we can drop the idea that the fight for gender equality has gone too far, hm?)  If you need a shot of hope after reading this, you might consider looking at the next generation of girls, who are increasingly vocal and visible right now—as you know if you spotted a picture of Greta Thunberg flipping off members of the European Parliament in your Instagram feed last weekend. Now this powerful and passionate demographic have a history book of their own: The largest-ever oral history of girls’ activism comes out this week, and it was feted Sunday by Malala in Kigali, Rwanda. Stories of Girls’ Resistance chronicles 150 activists from 90 countries—from Mamta in Fiji, who resisted arranged marriage (“stop marrying me off!” she exclaims), to Naomi in Kenya, who joined a strike on behalf of political prisoners when she was 17. The book is timely: “At a moment when we are seeing rising authoritarianism and attacks on human rights across the world,” co-author Jody Myrum and creative strategist Laura Vergara told the Meteor, “we need to invest in [girls’] resistance more than ever—both because girls’ rights are deeply under attack and because they hold the vision, strategies, and tactics to lead us to our collective liberation.” And—like Mattie Kahn, whose new book Young and Restless warns of the dangers of glamorizing young female leaders as singular figures without supporting them more meaningfully—the oral history sends a message that celebrating girls’ heroism isn’t enough. “Girls do not need any more ‘fame,’ ” said Myrum and Vergara, “but rather clear accountability and support for their work…They need to be meaningfully funded rather than treated as beneficiaries. Specifically for funders – it is time to take girls’ resistance seriously. Move significant resources directly to girls, not thousands but billions.” AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

A historic day for the pill

July 13, 2023 Hello again, Meteor readers, We are officially less than ten days away from the Barbie movie opening, and I don’t know about you, but I’m stoked. My boyfriend and I got matching outfits for the premiere, and today’s newsletter will actually be a 50,000-word essay unpacking the feminist significance of everyone’s favorite plastic doll.  Kidding! Today’s newsletter actually features a monumental step forward for reproductive rights, studio executives exhibiting “Christmas Carol” levels of villainy, trans people winning (what else is new?), and Justice Clarence Thomas’ latest ethics issues. Trying on every shade of pink I can find, Bailey Wayne Hundl  WHAT'S GOING ONA huge birth-control victory: For the first time ever, the FDA has approved a birth control pill for all-ages use without a prescription. Opill, a progestin-only pill to be taken once daily, is set to be available for over-the-counter purchase by early 2024, according to Perrigo, the pill’s manufacturer. How did this feel for contraceptive experts? “Like Christmas!” said Dr. Heather Irobunda, an OB-GYN and one of the founders of Obstetricians for Reproductive Justice. “I’m very happy this happened. It’s an important step in destigmatizing reproductive health meds.” And it’s hardly a radical step: Birth control pills are already sold over-the-counter in over 100 other countries. But this victory serves as a powerful message that birth control is safe and popular—at a time when conservatives are beginning to target contraception, both culturally and politically. As the director of the FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Dr. Patrizia Cavazzoni, pointed out, Opill is “safe and is expected to be more effective than currently available nonprescription contraceptive methods.” This decision does, however, raise questions we don’t yet have answers to:

And putting the pill—varieties of which have been safely used for five decades—on store shelves makes sense, says Dr. Irobunda. Keeping it prescription-only, she notes, signaled that “they didn’t trust us to know how to take it. This is a safe drug and can be easily managed, but ‘behind the counter’ made it something that we needed to consult with someone ‘who knows our bodies better’” in order to take. But as reproductive rights advocates have been saying this whole time, who knows our bodies better than us? AND:

WEEKEND READSOn abortion rights: Last election cycle, all six states with abortion on the ballot scored a win for abortion access. This cycle’s game plan: Do it again, but even better. On (un)fair pay: “Orange is the New Black” was huge for Netflix—so why wasn’t it huge for all the people who worked on it? On positive masculinity: Toxic male gender roles can be like quicksand for young men. But there’s a way out. On “doing the work”: The Meteor’s Samhita Mukhopadhyay explores how social justice organizations can be as active in supporting their staffs as they are in supporting their causes.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

The cops are sliding into your DMs

July 11, 2023 High vibrations, Meteor readers, It’s 7/11! All my numerology girlies just nodded while the rest of you are wondering why I feel the need to state the date. But ~mystically speaking~ when those two numbers appear together, they become a powerful and affirming “angel number,” which numerologists say can serve as a reminder to move forward within your intuition and a sign that the universe is open to providing you with new opportunities.  Meanwhile, here on earth: we’ve got a troubling update on a Nebraska abortion case, an AI lawsuit, and a fond almost-farewell to Megan Rapinoe. Reading the stars, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONPrivacy: Last week, a mother in Nebraska pled guilty to helping her daughter obtain an illegal abortion and discard the fetus after it was expelled. Now Jessica Burgess and her daughter Celeste, 18, are both looking at jail time for their actions. You may remember Jessica and Celeste’s case from last August, shortly after the overturn of Roe v Wade, when charges were first filed against them. What made the case unique was not simply the fact that two women were going to be tried for acquiring and using abortion pills in a state where it was newly illegal—but also the questions the case raised about data privacy. A refresher: After Celeste found out she was pregnant, she and her mother communicated via Facebook messages and came up with a plan to end the pregnancy and discard the fetus so as not to leave behind any evidence. Because Celeste was already 20 weeks pregnant and Nebraska bans abortion after 12 weeks gestation, the two knew they could not go to a medical provider to do any of this—hence the secrecy. They thought the messages they shared about the ordeal were private. But Facebook’s parent company, Meta, turned over their correspondence to the police after being served with a search warrant (pertaining to a different investigation)—and the police had what they needed to charge the mother and daughter. The case was among the first to highlight just how vulnerable abortion seekers, many of whom rely heavily on online searches for care, had become in the immediate aftermath of Dobbs. As Shamira Ibrahim wrote for The Meteor last year, apps that use location data and cookie tracking “help law enforcement investigate and prosecute abortion-seekers and their respective networks of support.” That’s exactly what happened in the Nebraska case. Now the women face up to two years in prison, and a man who helped them bury the fetus was also charged and given probation. If you or someone you know lives in an abortion-ban state and needs care, Ibrahim suggests visiting the Digital Defense Fund, which provides steps for protecting your abortion-related data privacy—from Facebook, the phone company, and anyone else you don’t want to know your business. AND:

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

Are legacy admissions inherently racist?

July 6, 2023 G’day mates, It’s been a busy few days this week. First off, Wimbledon is underway. I’m trying to turn my infant into a tennis prodigy by osmosis, so we’re really getting into these matches together. Once it’s over, we’ll be hitting the court to see what she’s learned.  Also having a busy week: Mark Zuckerburg, who launched his latest offensive in the battle of the billionaires in the form of a new social media platform called Threads. Elon clapped back by threatening a lawsuit. Keeping all of the social media managers I know in my prayers tonight. If you’re one of the 10 million people who signed up for Threads in its first hours of life, give us a follow! In today’s newsletter, we’re chatting about college admissions, the attack on Jenin, and checking in on Greta Thunberg. Working on my forehand, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ONOut of your (Ivy) league: The Supreme Court’s decision to eliminate affirmative action in college admissions is only seven days old. But Harvard, one of the schools at the center of the decision, won’t be getting any breathing room. On Monday, three civil rights groups came together to file a complaint with the Department of Education (DOE) against the school, challenging its use of legacy and donor-based admissions. The groups are arguing that these practices are in direct violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act and “are not justified by any educational necessity.” Quick refresher on what legacy admissions are: If Biff Moneysworth graduated from Harvard in 1999, then that means Biff Jr. will get special consideration when his application hits the admissions desk. Because Jr. is more likely to get in, that means one less spot for someone like Joanna, a first-generation applicant who has the grades but not the family connections. Considering that people of color weren’t allowed to even apply to Harvard (let alone any other Ivy league school) until after World War II, who is most likely to benefit from the maintenance of legacy admissions?  Harvard’s response to the SCOTUS decision and this latest complaint leaves much to be desired: “The University will determine how to preserve our essential values, consistent with the Court’s new precedent.” Yes girl, give us nothing. Obviously, this doesn’t mean that people of color will never get into Harvard, but the barriers just got a lot higher. And while affirmative action was an imperfect Band-Aid to the institutional racism that spawned legacy admissions, it was something. The groups behind the complaint are asking the DOE to investigate Harvard’s use of legacy admissions and decide whether or not it violates Title VI. They’re also asking the DOE to cut federal funding to Harvard unless the school removes legacy and donor considerations from the admissions process. If successful, this could once again change the landscape of college admissions—or at least force the courts to treat all forms of “preference” equally. But in such a secretive and subjective process, racism will always find a way through. As Dr. Anne A. Cheng told us last week, “The problem with college admissions is that it is itself such a vague process; it takes into consideration many factors, and every factor itself has the potential to hold racial and gender bias.” AND:

WEEKEND READSOn immigration: How Trauma Migrates tells the story of migrant women’s journeys across America’s southern border and the untreated trauma that lingers once they make it. On SCOTUS: Did the Robed Ones quietly legalize stalking? Sort of. On sports: The iconic Venus Williams was defeated in the first round of Wimbledon this week, but her legacy reaches beyond even her 11 previous title wins. On parenthood: Diaper legislation? It’s a thing. And with the loss of abortion access, the once invisible problem of “diaper need” is more glaring than ever.  FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend?

|

![]()

SCOTUS v. Affirmative Action

|

Greetings, Meteor readers, It’s an unfortunate day for higher education. This morning, the Supreme Court handed down a ruling that will effectively end affirmative action in the college admissions process, rolling back what Justice Sonia Sotomayor, dissenting, called “decades of…momentous progress” and presenting yet another barrier for students of color. As a Latina from one of the poorest counties in the state of New York, the process of getting into college was grueling—years of Latin to help me perform better on the SAT, endless extracurriculars, the pressure to get high grades, the money my mother shelled out for an exorbitant prep-school tuition bill. All based on the understanding that I would only succeed if I was extraordinary. Only to finally make it and get called a “spic” by a stranger who wrote it on my dorm room door. It’s laughable that affirmative action was seen as preferential treatment when, for many of us, it was simply a way to gain access to a historically white institution and then spend four years proving you earned your way in. In today’s newsletter, Samhita Mukhopadhyay talks to Princeton University professor Dr. Anne A. Cheng about the ways students of color have been pitted against one another in this debate. Thinking of all the multicultural student unions today, Shannon Melero  WHAT'S GOING ON

SCOTUSCutting Race-Based Admissions Will Not Help Asian American Students“Why do we assume that if you keep down the number of Asian Americans, you'll get more African Americans?” BY SAMHITA MUKHOPADHYAY  (IMAGE BY BILL CLARK VIA GETTY IMAGES) Today, the Supreme Court struck down the practice of affirmative action in college admissions. In two cases—one against Harvard and another against the University of North Carolina—the plaintiffs argued that considering race in the admissions process was a discriminatory practice, violating the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution. The decision has been looming for months, but its implications are yet to be seen. That’s partly because the cases themselves are complicated, bringing to the surface core tensions in affirmative action—who it includes, who it leaves out, and why we ultimately need it. I spoke to Dr. Anne A. Cheng—a scholar of Asian American and African American literature and cultural theory at Princeton University—about all of it. Samhita Mukhopadhyay: What were your thoughts when you first heard the Supreme Court would be looking at race-based admissions in colleges? Dr. Anne A. Cheng: It is very complicated. Affirmative action is an imperfect and yet still necessary solution to a very broken social system in America. I am stunned by how persistent the debate is around affirmative action. I remember a long time ago, when I was a graduate student at Stanford, I was stopped on campus by someone wanting to take a photo of me because they wanted it to go with an article about some scandal about Asian American admission at Stanford and other elite institutions. That was several decades ago, and it's like we are still there. The thing that I've been trying to parse out in understanding the implications of this case are narratives like the myth of the model minority and how often immigrant communities are pitted against the African American community. Some of the plaintiffs in this case are Asian American students who believe that Black and Latine students were picked above them. Do you think there is validity to that anxiety? There are two different anxieties that I always see around this issue. One is Asian Americans feel like…there's a quota on them. [The Harvard case argued that Asians were discriminated against because race-conscious admissions led to Asian applicants scoring lower marks on traits like likeability, whereas the UNC case argued that Asian and white students were denied admission, their spots taken by Black and Latine students]. But there is [an] anxiety about Asian Americans overrunning American universities. And so, you're right...Somehow, affirmative action—at least race-based affirmative action—always seems to imply that it can only benefit African Americans, not also Asian Americans. College admissions, as you can probably guess, is an extremely closely guarded practice, and faculty are kept far out of it. We know nothing about undergraduate admission. The admission office [doesn’t] ask us for counsel. They don't ask for opinions. They don't even tell us anything. Would I be surprised to find out that there is a quota? No, I would not be surprised. It’s such a complicated process. Even if you say something like, ‘We're not looking at race at all, we're looking at a well-rounded individual.’ Well, what constitutes well-roundedness, right? Some Asian American or Asian students might say if you are an applicant and you are Asian American and, let's say, you are interested in science—you are immediately pegged as this nerd that's not well-rounded. There are all these stereotypes at play. And so I think that part of the problem with college admissions is that it is itself such a vague process; it takes into consideration many factors, and every factor itself has the potential to hold racial and gender bias.  BLACK AND ASIAN STUDENTS PROTESTING ON DIFFERING SIDES OF THE AFFIRMATIVE ACTION DEBATE JUST THIS MORNING. (IMAGE VIA ANNA MONEYMAKER VIA GETTY IMAGES) I think that's why this case is so complicated. One of the things the plaintiff is arguing is that Asian American students were more likely to be ranked as not being well-rounded or having lower marks in personality or certain softer skills, which is a type of implicit bias. Yes, it's a very, very, very stubborn and old bias. There's a psychology study done by a psychologist called Susan Fiske. It's called a warm competency test, where she interviewed a bunch of people about their perceptions of Asians and Asian Americans in America along two vectors. One is, are they warm or are they cold? Like: likability. The other question is, are they competent? As you can exactly guess the answer, most people—that is to say, most non-Asian people—found Asians to be competent but unlikeable. This unspoken, unconscious bias is not just Asian Americans, but African Americans and Latinos, too. When you talk about a well-rounded person, we're also talking about, in many cases, the question of class. If you're from a middle-class family, then yes, you had the opportunity to take cello lessons and play soccer and do whatever. But if you come from a lower-income household, there's much less opportunity for you to be a tennis player and a chess player. That kind of well-roundedness has a class dimension. How do I say this? From my reading, there may be validity to the idea that Asian American students applying to Ivy League schools experience some kind of discrimination. But the solution is not to strike down affirmative action—it could also be to expand affirmative action implementation so as also to include Asian Americans. Because ostensibly, it's supposed to, right? Well, there's been a lot of debate about that. I think that [sometimes] affirmative action does not include Asian Americans because they're not considered minorities in certain places. The other thing that's sort of very vexing is that there's a sense often that the so-called “too many Asian Americans” [are] taking spots away from other racial minorities, rather than the fact that they're taking spots away from whites! Why do we assume that if you keep down the number of Asian Americans, you'll get more African Americans? It's weird. Right. I mean, that's why it's a red herring. It's not real. It's a total red herring. All it does is, I think, drive the wedge between Asian Americans and other racialized minorities. It doesn't actually acknowledge that when it comes to elite institutions, I think the anxiety should be much less about how many Asians there are and much more about how they are treated once they are here. That’s true for African American students and Latine students, too—admissions is only one part of this. Yeah, absolutely. It's not just about letting them in. It's about creating a culture in which they can thrive. What do you think is the best strategy for universities to retain the most diverse talent they can? I wish that institutions would think about diversity as a genuine intellectual project and not as a numbers game. Because if they thought it was a genuine intellectual project... The number games mean that you try to get the numbers up so you look like you are an anti-racist institution. But if you're serious about it, it means not only making sure diverse people get in, but also that you are ready to foster these diverse people. You're ready to meet them where they are and then nourish them and help them grow. Do you feel anxious about the outcome of this case? I do…Young people, what they really need is a chance, an opportunity. That's what affirmative action does: give an opportunity to someone who may not otherwise get it.

FOLLOW THE METEOR Thank you for reading The Meteor! Got this from a friend? Sign up for your own copy, sent Tuesdays and Thursdays.

|

![]()